14 minute read

Artwork as a confidential conversation with the viewer

Mikhail Rogalevich is one of those Belarusian artists who left a unique mark on the national fine arts

Advertisement

Today it will not be an exaggeration to say that the art of Mikhail Rogalevich touches the most intimate in the souls of people — the genetic striving of Belarusians for spiritual purity, sublimity, admiration for the beauty of life and the dignity of the human person in it. But it’s hard even to imagine that an artist who was destined to go through incredible trials by fate, who got orphaned as a small child in the pre-war period, will be able to preserve faith in human and humanity in his soul, and even speak about it at the top of his artistic talent.

Where did the artist get his spiritual energy and strength from? Maybe they gave them a towel embroidered with small horses — the only relic and all the legacy that remained from the parents. It is not for nothing that we see it in many works by Rogalevich. Or maybe he was inspired by the only surviving picture of his mother — a very young girl with long beautiful hair and light eyes. The artist dedicated several paintings to her.

In his paintings, he glorified the quiet, complex, at times contradictory, but largely filled with popular optimism and inner enlightenment, life of former peasants who moved permanently from the village to town. Rogalevich was the first, and perhaps the only one among Belarusian artists, deeply and consistently, from year to year, to reveal this topic, speaking through painting about the achievements of spiritual culture that a rural Belarusians brought to urban life — a tradition-filled cult of family relations, optimistic percep-

tion of the world, kindness in relations with people. The artist began to exhibit his first works on this topic at republican small exhibitions back in the 1960s, when most of his colleagues, often ashamed of their peasant origin, dedicated their works to

M. Rogalevich. Self-portrait

reflecting industrial processes. The theme of sincerity, the majestic beauty of human relationships in the family was one of the leading in the work of Mikhail Rogalevich.

His artistic activity is also distinctive because he was the first among Belarusian artists to reveal through art the truth about the tragedy of the people, which he himself experienced during the repressions in the pre-war years. These were rather intimate pictures that revealed the pages of his personal biography, the personal tragedy of Rogalevich and his parents, the pain of which did not subside for a minute. But at the same time, these were truthful, painful, bold steps towards great truth.

Without a doubt, he is one of the most profound in the meaning of creativity and figurative imagery of contemporary artists. It is also obvious that his paintings bear the essence of the Belarusian mentality, concentrated on the priority of family and family relations in a person’s life.

It is not in vain that the first personal exhibition of Mikhail Rogalevich in 1983 became a sensation. Almost the entire Palace of Art in Minsk was occupied by his paintings. More precisely, more than a hundred paintings and about the same number of graphic sheets (only a part of his creative achievements) filled the space of two floors of the country’s largest exhibition pavilion with the energy of images and colors. It was an unprecedented intellectual “fireworks-

performance” of the harmony of vivid emotions, deep feelings and experiences, unprecedented before that time within the walls of the gallery — the artist’s piercing confession to his compatriots.

Until that exhibition, little was written about the artist: his art did not fit into the notions of socialist realism and stereotypes of evaluative standards, polished over the years. However at the time of the exposition, other moods were already beginning to arise in society. An amazing thing is that the work of Mikhail Rogalevich received due support. After Minsk, his exhibition was successfully displayed in Molodechno and Mogilev, Gomel and Vitebsk. The press responded to the events with the publication of detailed articles-reviews. Rave reviews, in particular, were published by the weekly “Literature and Art”. Rogalevich’s high critical appraisal was adequate to his work, which, with its purity and openness, confidential conversation with the viewer, simple attitude to life, was perceived as a breath of fresh air, as something unusual but very necessary. At the same time, the magazine “Mastatstva” in one of the issues told about the work of Rogalevich on almost all of its pages — an incredible event which never repeated again. The National Museum of Art had never paid so much attention to one artist before — a largescale exhibition “Song of Life” was located here on two floors. There could have been more, but collecting all the iconic canvases in one place turned out to be problematic.

Yes, he was naive and courageous. When he was the first in Belarusian art to raise the topic of Stalinist repressions, and when he recreated on canvas the life of new townspeople who had moved from the village along with their grandfather’s customs and gullible openness. He painted red-headed babies, lovers on a rearing up horse, countless apple trees and apples, long-necked women with bouquets of roses — but not the portraits of leaders and not industrial landscapes. Neither at the time of “developed socialism”, when it was a common practice, nor later, when many of its creators became ironic over the bygone era and its values. Rogalevich’s art has been evaluated and re-evaluated many times. Including in the most literal, monetary sense, although in principle he himself did not sell a single work to private collectors. Only a few canvases and only to state museums, and he immediately painted — no, not copies, rather, versions of paintings that had gone into museum collections. From the point of view of some, he was

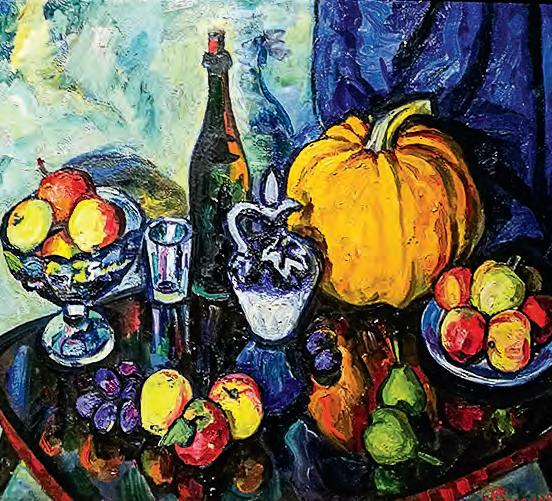

M. Rogalevich. Still life 1977 year

a genius, others considered him a dropout — not even because of his education limited by a diploma from the Minsk Art School, but by the manner of painting stylized as primitive folk art with its bright colors and spontaneity of village carpets — “malyavanka”. In an ingenuous desire to tell about everyone he loves, without fear of looking sentimental. However, no other canvases recreate the past so visibly and documentarily. Despite the conventionality of the drawing, all everyday details in the paintings of Mikhail Rogalevich are accurate and recognizable, the landscapes are concrete, and the portrait images are extremely similar to the people he portrayed.

At the personal exhibition of Mikhail Rogalevich at the National Art Museum

People were not fictional — always real and loved.

He made many sketches for each of his paintings. He left to posterity a huge number of graphic works, many times more than paintings. “His graphics are another planet,” art critic Tatiana Garanskaya is convinced. — In terms of its level, it is quite possible to compare with the amazing drawings by Vrubel, for example. They are so virtuoso — Rogalevich really was a high-class professional. He went through a colossal creative path, born as an artist in the era of “severe style”. Although in his early works we see the bright features of expressionism: all feelings are naked, the colors are dramatic, saturated.

He painted his wife as often as Modigliani painted his muse Jeanne Hébuterne, only the hands on all the female portraits by Rogalevich are different: inelegant, overworked. Sometimes he associated himself with Van Gogh — his road to art and recognition was just as long.

Family for Rogalevich was an absolute value. The real beginning of the life of the red-haired boy was completely different than on most of the canvases that he painted. The reason why his father was sentenced to death, and his mother — to exile to Siberia, remained a secret for Mikhail — he himself was not even a year old then. Both were from old noble families, but all that was left to their son was a few photographs and a towel embroidered with horses. Years later, he more than once introduced this towel into the space of his light works. After the parents were acquitted, they were compensated for the cost of the house that had been taken from them in the 1930s. With this money, Rogalevich built a cooperative apartment, moved into it with his family from the barracks and got his first studio — right at home. However, after a few years, his daughter Lyudmila Protskevich recalled, he was ready to give up everything: — Art did not feed my father’s family, and in 1978 we planned to move to Sakhalin for work. Almost everything was ready — the apartment was rented out, the containers were collected. Suddenly, almost on the doorstep, he received a letter with a proposal to join the Union of Artists. All things were immediately unpacked. We never left anywhere. Joining the Union of Artists was more important than any money.

He himself was satisfied with everything and with the absence of everything. Fanatical artists, as a rule, are unpretentious people, and Mikhail Rogalevich was definitely one of them. Even when he could afford some things, he preferred to pour the soup into the same aluminum bowl. All his life. Rather, it wasn’t just a fad, though.

Mikhail painted cold stones and stormy Siberian rivers in his early landscapes from nature. Working on the railroad, he used the right to choose any free route once a year and went to where he spent his early childhood. In the first transportation, Anna Rogalevich, the mother of the future artist, was allowed to go with her son. There he became seriously ill, but by some miracle she was able to return home with him. In 1937 — a new arrest, the son ended up in an orphanage. He escaped, wandered for a long time, but by the end of the war he managed to get to his relatives — the family of his father’s brother, who was shot in

Near the artist's works that do not leave the viewer indifferent

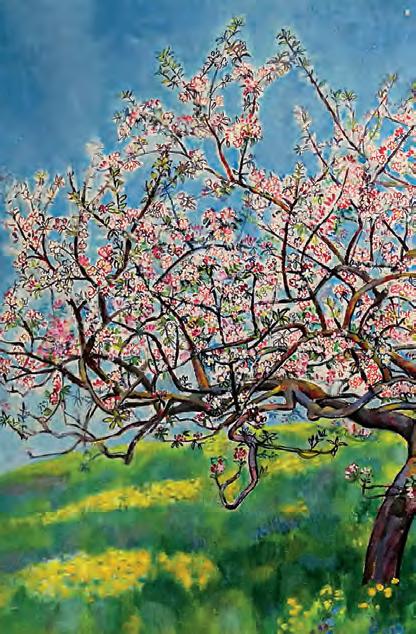

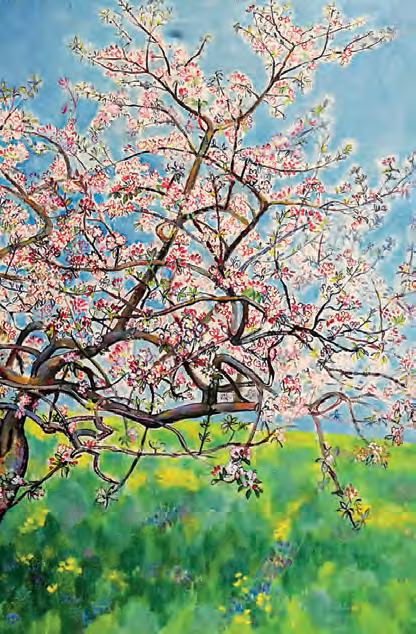

the same 1933. Apple trees bloomed profusely in their garden then…

Before the art school, Mikhail Rogalevich managed to acquire more than one profession. He worked in a foundry, as an excavator, a rail-layer. He met his beautiful wife not in a romantic setting, but at a construction site, where both worked. His muse was very earthly, very reliable. With her, Mikhail got what was most important to him: family and the opportunity to become an artist. This muse took over the whole life. Her portraits and other paintings by Rogalevich began to appear at all

exhibitions. True, he did not wait for titles, and a full-fledged workshop did not appear immediately.

However, Tatyana Garanskaya had a place to bring the students to introduce them to the artist, whose work literally discouraged with its diversity: — Mikhail Rogalevich spent most of his creative life at the Institute of Physics of the National Academy of Sciences, where he worked in such a funny position as a graphic designer. But thanks to this, he had at his disposal almost an entire floor, where favorite character for many paintings there was a study-studio, a warehouse for his paintings, and a grateful audience. There Rogalevich created a whole gallery of portraits of representatives of Belarusian science of his time, and in the hall of the institute his works were constantly exhibited, which he changed all the time. He just didn’t sell his works, he never looked for profit from his work.

Mikhail Rogalevich painted portraits of both ordinary scientific workers and famous professors and academicians. Many of these works were exhibited at republican group and personal exhibitions of the artist, some were acquired by museums. The peculiarity of those works is that they reveal the artist’s view of scientific workers as people, on the one hand, ordinary people, and on the other, often defenseless in front of life and its everyday problems. The artist endowed each of his heroes with archaic earthly beauty, which has nothing to do with secular representations, but is associated with the physical and spiritual originality of the prototypes of the paintings. Through capacious artistic images, the creator identified people who were close and dear to his heart and himself with images of nature, which he painted a lot and soulfully. Mikhail Rogalevich also painted the image of a hardworking woman subtly and sincerely, as an important accent of his own art. On such works as “Belorusochka”, “Present”, this image appears self-sufficient, detached from thematic cycles. On others, it permeates the family cycle of work and carries a cosmic feeling of respect and admiration for the dignity of women workers (“Mistress”, “Evening”, “Morning”, “They’ll go to reap”). This becomes obvious when you look through the legacy of the artist’s graphic works, where a series of drawings made on the themes “the one that sews”, “the one that knits”, “the one that washes”, “the one that cooks”, “the one that reaps” and the like… Each of them is an example of a virtuoso drawing, a clearly expressed nature, a strong energy of strokes and tonal spots.

Based on this, you understand that paintings are only the visible part of the iceberg of Mikhail Rogalevich’s colossal creative potential. The artist admires the figure, movements, harmony of a woman in her eternal pursuits and deeds. In some paintings, the artist raises a woman to monumental grandeur, in others — gives her the figurative characteristics of the goddesses of ancient mythology, who “spun the threads of life” or “solemnly sorted out the beads of time.” It is those works where the artist guessed and clearly, symbolically showed the viewer something intimate, deeply hidden in a woman, but truly worthy of glorification, are Rogalevich’s noticeable creative heritage.

The image of a hard worker, a keeper of family warmth dominated Rogalevich’s paintings for a long period. But gradually the artist gives preference to a woman as a symbol of splendor, her unearthly creation.

The process of idealizing the image of a woman unfolded throughout the entire

An apple tree in the spring is M. Rogalevich's

creative path of Mikhail Rogalevich. That is

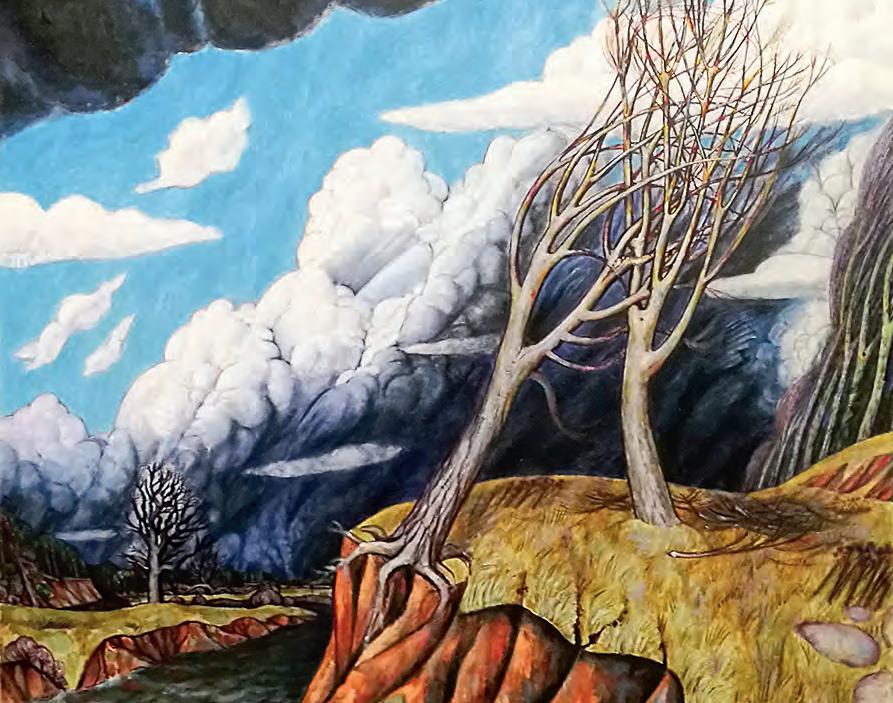

M. Rogalevich. About time and about myself

why it seems to many that the artist painted the same model, and in this he is consonant with Botticelli or Modigliani. Indeed, there were few prototypes of his female portraits — his wife, daughter and mother. However, there was another synthesized, deduced as a formula, image — Muse.

The most idealized female images are Anna in the painting Anton and Anna, in the plot about lovers in the “Tree of Life”, to a certain extent in “What a wonderful world”, where the artist poeticized the image of a girl that does not even run, but soars above the ground with a flower in her hand. Finally, the ascension itself took place in the plot of the painting “Birthday”. But the defining division between the real, life image of a woman or girl and giving it an unearthly, cosmic significance occurred at the stage of the artist’s creative comprehension of the image of a mother who died in Stalin’s camps during Mikhail’s childhood. He repeatedly, like an icon, painted her portrait, peering into a small, miraculously survived passport photograph, on which a young woman with beautiful curly hair, Anna Rogalevich-Alenskaya, was captured. This is how a series of portraits “My mother” appeared, later — the paintings “Mother in a distant land” and “Memories”, imbued with high drama.

In the painting “Memories” a vivid metaphor appears, which later did not disappear from a number of dominant archipelagos in Rogalevich’s art — a bush of crimson-red roses. The artist associated the image of this flower with sharp thorns with unbearable pain and his memory, as well as with the memory of an entire people about the bitterness of many losses during the wars in every Belarusian family.

Quiet, modest, even shy — this is how many remember Mikhail Rogalevich. However he persistently refused collectors. When he fell ill, his wife was scared. Not for the fate of his very impressive collection

Minsk gallerist Alexander Ivanov is a great admirer of the work of Mikhail Rogalevich of paintings, which it was not clear where to put, but for him He hardly understood what was happening around him, and she still hoped to cure him. She sold paintings without bargaining. No one — not the children, not her husband’s friends — dared to argue with her.

“About time and about myself” — so he called one of his later works. Two trees on a cliff, tightly bound by branches. Equally defenseless under the pressure of the wind, although only one has bare roots. His wife did not survive him for long. However, the paintings turned out to be stronger than time.

As well as the image of an apple tree, which, without exaggeration, became not only the starting point of Mikhail Rogalevich’s work, but also his original brand. The artist painted dozens of works with blooming gardens and panoramas of spring. Painting apple trees in bloom, he was looking for his own soul in the renewal of nature. For him, it was an opportunity for spiritual relaxation, since he himself lived a difficult and in many senses tragic life.

Yes, Mikhail Rogalevich often conceived a picture as a metaphor for a person who, like that tree, has to be in constant fluctuations between earth and sky, between existence and life. The artist believed that in order to live, not exist, and wait for a clear sky, you need to look for support, primarily spiritual.

Since Rogalevich’s art is basically autobiographical, the title of one of the main works of the artist — “About time and about myself” goes well with it. A drama unfolds on the bank of the river: one of the two trees that has moved away from the common heap of their own kind finds itself on the edge of a cliff and is about to fall into the seething stream of the river, the roots and trunk are already hanging in space. But it is securely supported by the steep branches of a neighboring tree. They, as if embracing, are strongly intertwined, and it seems that the terrible clouds of a thunderstorm are beginning to disperse, and between them the long-awaited breakthrough of the clear sky appears and sparkles… By Veniamin Mikheev. Photo by Author.

M. Rogalevich. Girl and sunflower. 2000 year