20 minute read

Where did the ghost come from in the town hall

OR WHAT DID THE 18TH CENTURY LEAVE FOR MINSK?

In the 18th century It would have taken you less than ten minutes to walk from the outskirts to the centre of Minsk. Yes, the city was small at that time, with only five thousand inhabitants, but by the end of the century its population grew by another thousand. To compare: at that time 20 thousand lived in Vilno, 7 thousand in Mogilev and 3 thousand in Novogrudok.

Advertisement

Unfortunately, we know little about the events that took place in the city two hundred years ago. Just think: there hadn’t been a war in Belarus for about 80 years — there hadn’t been such peaceful centuries before. And life was thriving in the city. The town hall was the seat of the town council, supervised by the councilor. It consisted of a council and a lava. The former dealt with public affairs, the latter was responsible for criminal cases. The lava could only try ordinary citizens, but it was difficult to influence the nobility. This is why there were many disputes at that time. The gentry bought lands inside the town and once they were bought, they fell out of the town’s jurisdiction. It led to serious problems. When a nobleman bought two plots on different sides of the road, he merged them, thus blocking the town’s tracks.

The village headman was appointed by the king. Naturally, this position was taken by a big nobleman, who was often ready to sacrifice the interests of common burghers, so as not to quarrel with the richer and more influential masters.

Minsk was also the seat of the voivode, for the town was the centre of the voivodeship. Every two years tribunals were held there, at which representatives of rich clans appeared. It is easy to imagine that serious political games were played here…

One can learn about the18-century secrets of the capital during the author’s journey held by the guide Timofey Akudovich. Within the project “Drawing closer” he teaches to notice details, to read history from the objects that have survived in the city, and to admire it.

The Emperor, the treasure and the “showdown” of monks

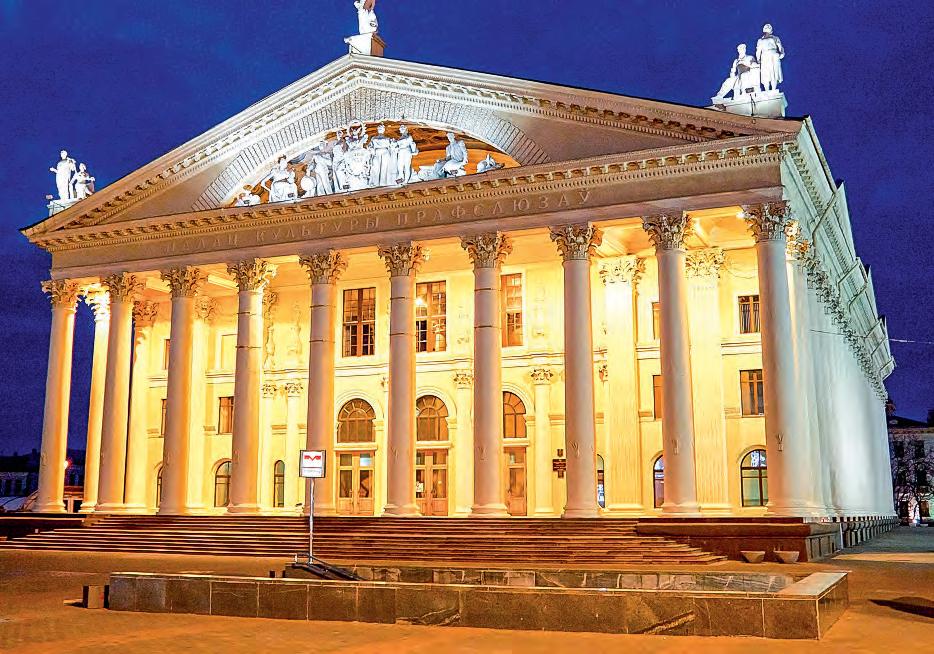

The journey begins on Oktyabrskaya Square. More precisely, we get to the ancient Yuryevskaya (onsite the modern House of Trade Unions there was the Uniate Church of St. Yury) and Dominikanskaya Street.

If you happen to stroll next to the Palace of the Republic, you might imagine that one of the city’s most beautiful buildings used to stand there, surrounded by a garden where pears imported from Europe used to grow. Allegedly, it was from here that they spread throughout Belarus, and the variety was named Sapezhanka. This two-storey palace belonged to the Sapieha family. During the Great Northern War Peter the First stayed there for several months, as the Russian emperor decided to annoy his rivals. The fact is that the Sapieha family were among those who did not support their eastern neighbour, but sided with Karl the Twelfth. From here Peter the First planned a series of events. There was another important secret about the building. The parents of the future Empress Catherine the First served in the palace, after which the couple moved to the Baltic States, where their daughter was born. She grew up to be a beauty and, despite her not very noble origin, she managed to win over Peter the First. Back in the 1920s the building stood on Yuryevskaya street, but it was badly damaged and destroyed during the war.

There is a sign behind the Palace of the Republic reminding today that the ruins of one of the largest Minsk churches of that time, i.e. the Dominican Church, are hidden under the ground. The place is now empty, and the question of restoring a temple comes up from time to time..

Old sources recorded that the church was built on a “hoof tax” — they said that when the warriors returned from war, the Dominicans asked money “for God” as a sign of gratitude for saving their lives. A gold piece was paid for every hoof of a horse. The order was very rich: when the monks were completing the building of the monastery, to produce bricks they rented a brickyard near Minsk in St. Peter and Paul Church. Until the 19th century, it was rumored that somewhere in the dungeons, the Dominicans hid treasures (there was also an underground passage here). And in the 90s of the 20th century journalists recorded a story told by taxi drivers who many times had seen a dog running across the road with a torch in its teeth. One might think it’s not a big deal. But the thing is, a dog with a torch is a symbol of the Dominicans.

The story goes back to the old days about a fight between monks, which apparently happened because of schoolboys who had first studied at the Jesuit college and then “switched” to the Dominicans. But after the fight, the students were forced to return to their previous place.

At the time, the monks determined certain fields of work for themselves. Some healed, others taught, the Dominicans were engaged in printing, they devoted a great deal of attention to theology. One of the most influential preachers at the time was Priest Obłaczyński, and crowds gathered for his speeches. During one of his anti-drinking sermons, the theologian mentioned perhaps the most vicious troublemaker of the town, the debaucher Michał Wolodkowicz. The nobleman then took revenge on the priest — during another service he drove into the church with a barrel of wine, gypsies and bears. Obłaczyński then warned that Wolodkowicz would surely pay for such an act. Naturally, the priest did not succeed in frightening the reveler. Wolodkowicz got away with everything, for he was known as a friend of the magnate Panie Kochanku.

But who could have imagined the terrible expiation…

Crime and punishment

Michał‘s brother Józef Wołodkowicz was also a troublemaker. One day he quarreled with his old neighbour Jacynicz over land. How could Jacynicz compete with the young merchant, especially when he had such influential friends? The old nobleman ordered his servants to put a pile of straw in the middle of the yard and thresh it, and he walked around asking, “Whom do you beat?” And the servants were supposed to answer “Wołodkowicz”. After a while the young neighbour invited Jacynicz as if to make peace, but ordered his servants to seize the “guest” and beat him in the yard, and to answer the question “Whom do you beat?” with “A heap of straw”…

Of course, the old nobleman could not bear such an insult. He went to court, turned to different authorities, he even managed to get Wołodkowicz to pay the fine and stay under house arrest in a monastery for a few months. Only the punish-

BELTA

Sculpture of village headman with keys near

the Minsk town hall ment was too mild — at the monastery, for which his family had previously donated money, Wołodkowicz used to walk with his entourage. Eventually the old nobleman appealed to the tribunal, and then the games of the elite began. The Czartoryski, wishing to annoy Radziwiłł, insisted on Wolodkowicz’s guilt. Józef’s brother

Generally, the 18th century was a time of serious shifts in all the spheres: scientific discoveries, new music, dances and fashion. Whereas in Europe the changes were slow, in our land the baroque style stayed for a long time. The men, who adhered to the Sarmatian style, did not want to adopt European fashion with wigs and silk tights for a long time. Women were more flexible, they quickly grasped the secrets of European beauties. At the beginning of the 18th century, they got rid of the black colour that had been popular in the previous century, their clothes became more revealing. Etiquette became more elaborate, more cutlery appeared on the tables.

Michał Wolodkowicz was also present. Indignant at the decision, he drew his sword, attacked the tribunal and even accidentally cut up a crucifix. After that he encountered a funeral procession, turned it around, made a lot of noise and got drunk… The Czartoryski decided to use such an opportunity to do more harm the Radziwiłłs — they applied to Vilno for permission for a serious punishment.

The friends informed Wołodkowicz that he was going to be killed. Only he did not believe him. But Michał was punished. The ghost of Wołodkowicz is said to haunt the town hall. It is one of the most tragic stories of that time — for the first time a nobleman was executed — without a confession — and why? For drunkenness and unbridled temper? It is no coincidence that memoirists of the late 18th and early 19th centuries referred to it so often; it is recorded in several variations.

Infrastructure

The Tribunals — the Grand Duchy of Lithuania’s greatest court — were held at the castle. Cases concerning the territory of eastern and central Belarus were decided here. Sessions dragged on for months, which meant that all arriving guests had to be provided with lodging and entertainment. The magnates built themselves houses to have

a place to stay. Thus, the Radziwiłłs built a palace onsite the modern-day Hotel Europa. Another important event for the provincial town were sejmiki, which brought together the nobility. Naturally, they solved serious problems, but also tried to have fun. The first cafes might have appeared in Minsk in the 18th century. At any rate, coffee, the beverage fashionable in Europe, was present in all wealthy households; some even had a servant, who made coffee. But tea came to the Belarusian lands only in the nineteenth century.

Great emphasis was placed on education. To the right and left of the Church of the Virgin Mary (now Liberty Square) there was a Jesuit college and school. It was here that new teaching methods were used. The Jesuits are said to have invented the classroom-lesson system, as well as various methods of stimulating learning, and they were the first to decide that children should have PT lessons. The Jesuits owned a whole block in Minsk, you could even make a separate museum dedicated to this order.

Another old buildings, i.e. the Pshezdeckis’ Palace, has survived in Liberty Square. Today, the Mikhail Savitsky Art Gallery is situated there. Anthony Pshezdecki was a middle-class nobleman. He managed to make a good career, all because he was loyal to the Czartoryski princes and was generously rewarded for his services.

In the 18th century the city was still densely populated with wooden houses, so it suffered greatly from fires. But there was a strict rule: if a house burned down, the owner had to build a brick house in its place, otherwise he could be ousted from the city. Therefore, in the 19th century, By Elena Dedyulya

Minsk began to change its appearance.

The Sapieha Palace used to stand on this site, now here is the Republican House of Trade Unions. Minsk, 2020

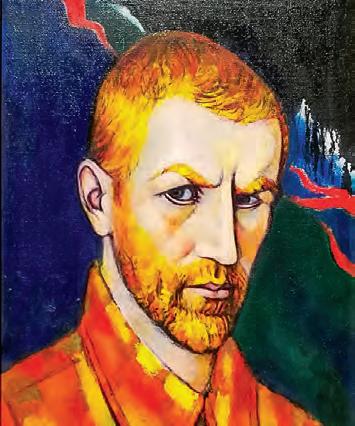

LATIN SONG OF THE BELARUSIAN SOLOMON

The first person to call himself a Belarusian was a poet born 460 years ago

“Stop, stranger, whoever you are, and forgive the small and the great, the greater and the lesser. You will find that eternity under God is nothing, in an instant the significance of great things collapses and is destroyed.”

The poet, born 460 years ago, included these words in his poetry collection — in Latin, of course, because Latin is the language of the universal, something by which the educated people of Europe recognized each other…

And in the acts of the University of Altdorf for December 2, 1586 he recorded himself as “Solomo Pantherus Leucorussus” — Solomon Pantherus the Belarusian. And this is also how he called himself in his correspondence with his German friend Konrad Rittershausen.

Thus, Solomon Rysinski went down in history as the first to call himself a Belarusian and his country — Leucorossia, Belarus.

Knight with a sword in the moonlight

460 years since his birth. Of course, because of such a time veil not much can be seen. Even the place of birth of this man was named differently — most probably, the poet and thinker Solomon Rysinski was born into the family of a poor nobleman Theodore Rysinski in the estate of Kobylniki in the Vitebsk Region. His coat of arms was “Ostoja” — a knight’s sword between two crescents, the memory of how the knight Ostoja destroyed an enemy camp in the moonlight.

But Solomon was destined to conquer with words more than with a sword.

He was, however, born in times of war, and was brought up undoubtedly as a nobleman. Future warriors were not allowed to be excessively spoiled — in infancy some were awakened by a shot in the ceiling, they could be sent at night with a certain task, for example, to pluck a couple of ears from a neighbouring field. So that they would have no fear and would get used to following orders without hesitation. When a duke or king declared a mass mobilization — a nobleman was to leave feasts, hunting and a young wife and immediately join the army. If it’s a matter of honour — wash it off with blood, if your manor is attacked — defend it…

But it is clear that Solomon also had a thirst for knowledge since childhood… He was sent to a foreign nobleman’s court to receive elementary education. There the bright lad was noticed by the courtiers of Duke Jerzy Radziwiłł — it seems we are talking about the future bishop of Vilno, the son of Mikołaj Radziwiłł Czarny. This is evidenced by the fact that Jerzy Radziwiłł was studying at the University of Leipzig, and Solomon Rysinski was also sent there with his support.

At that time Jüri was still, like his father, of the Protestant faith, but later he and his brothers became staunch Catholics. In the meantime, poor but smart Solomon entered the University of Leipzig, its church in 1545 was consecrated by Martin Luther, the spirit of the Reformation was alive there and medieval scholasticism was replaced by humanism.

Alongside Seneca and Reformation

There is no doubt that Rysinski absorbed all the progressive trends and knowledge, and he could not get enough of it. After all, he subsequently entered the University of Altdorf near Nuremberg. And of course, his poetic gift helped him to fight his way — at that time every educated person was supposed to be able to write an ode, an epitaph, a madrigal. It was not for nothing that together with the mentioned friend Rittershausen Rysinski he commented on the Roman poet Ausnius, on Ovidius, Plautus, Claudianus, analyzed the letters of Seneca. He wrote in Latin, used Polish… But he also wrote in his native Old Belarusian. Researchers found three of his epigrams in the Vilna editions of Mamonichi: “On the coat of arms of the most illustrious Ostafi Wołłowicz…” (1585), “On the coats of arms… Lew Sapieha” (1588), “On the coat of arms of the Grand Duke… Teodor Skumin” (1591). He also translated from Belarusian into Latin the poems of another Byelorussian poet of his time — Andrzej Rymsza.

Let anyone doubt the antiquity of the history of Belarusian literature…

One can imagine how in the context of ripening national ideas, in the crossroads of Europe, the young thinker Rysinski comprehended his belonging to a particular nation and the place of that nation. He didn’t consider himself a Pole, a Lithuanian or a Russian. That is why the term “Belarusian” was needed. As a proof, researcher Oleg Latyshonok quotes Rysinski’s letter to Rittershausen about the use of possessive adjectives: “Even now Moscovites, Belarusians (Leuсorussi) ZVIAZDA.BY and most of Lithuanians use it often”.

It was there, in Altdorf, in 1587, that Rysinski published his first book — “Epistolarum Salomonis іbros duos”, letters to relatives, deceased and fictitious persons.

Above all Rysinski put the skill to express the thoughts beautifully: “I warmly love those who appreciate and respect the dignity of this gift, so, on the contrary, those who either do not understand or despise such a wonderful display of art, I reject and believe that they are hardly worthy to be called people.”

A teacher for wealthy heirs

A man of science, courtesy, and even a poet — the tycoons were willing to go to great lengths to get him as a teacher for their offspring. Let me remind you that Symeon Polotsky, a Belarusian, when he came to Moscovia, impressed everyone with his poetic prowess, among other things, and became the tutor of the future Peter the First.

Solomon Rysinski also began a career as a domestic tutor. He tutored youngsters and accompanied them abroad. Finally, he came to Krzysztof Radziwiłł nicknamed “Perkūnas” and became court poet and mentor to his son and, later, grandson. It was about the powerful Perkūnas, who earned his nickname for the “scorched earth policy” he used during hostilities, that Andrzej Rymsza wrote his poetic tale.

The Radziwiłłs, as we understand, were not known for their meek characters. When Rysinski came to Perkūnas’ court, and scholars believe it was in 1596, the prince was married for the fourth time. He had a son Janusz by his second marriage to Katarzyna Ostrogska, who died soon after giving birth. The third time Perkūnas married was to Katarzyna Tenczyńska, who was older than him and had children of her own. She was the widow of Slutsky to be protected from the onslaughts of her husband’s relatives…

No one gave permission for the marriage, the Pope did not respond as Perkūnas was a stubborn Protestant, his coreligionists all over Europe also refused… So Krzysztof Radziwiłł didn’t give a damn about all the conventions and got married.

If we count, we will see that at the time Rysinski appeared in Christophe Perkūnas’ court, he was about 26 years old, while Janusz Radziwiłł was about 17. Not such a big age gap, and Janusz was probably educated in Europe at the time. So the educational talent was probably directed towards Perkūnas Radziwiłł’s youngest son, also Krzysztof, by his marriage to Katarzyna Tenczyńska, who was born in 1585.

At the crossroads of magnate intrigue

All the studies say that Rysinski was not just an educator and court poet, but for Perkūnas he became an advisor, a like-minded man in Calvinism and in the fight against the Arians. Arianism — a branch of Protestantism — was Krzysztof Radziwiłł nicknamed "Perkūnas", then in force in the principality, at whose court Solomon Rysinski worked and on the lands of Jan Kiszka, the first husband of Perkūnas’ fourth Prince Jerzy Olelkowicz, and had immense wife. It is said that Perkūnas also sought a wealth. And in 1593 a widowed Krzysztof scandalous marriage in order to dissolve Radziwiłł Perkūnas married for the fourth Kiszka’s will, to drive out the blasphemers time, to Elżbieta Ostrogska, which caused and to close the Arian schools and printa scandal not only in Lithuania’s lands ing houses on the lands received with his but in the whole of Europe. It is not that wife’s dowry. the fourth marriage was considered a sin Rysinski, a good polemist, could not and a special permit had to be obtained help participating in disputes with the for it. But Elżbieta was a birth sibling of Arians. Nor could he stay away from the Perkūnas’ second wife, Janusz Radziwiłł’s events surrounding the marriage of Janusz aunt. This was considered incest. Radziwiłł and Sophia of Slutsk, the grand-

It took Perkūnas a long time to get daughter of Perkūnas Radziwiłł’s third permission to marry — and not because wife, Katarzyna Tenczyńska. An orphan of any love at all. It was because Elżbieta and wealthy heiress, Sophia was a most Radziwiłł was the widow of Jan Kiszka, tempting bride for the greedy magnate. But the vaivode of Brest, and had huge estates, her guardian Hieronim Chodkiewicz and with Perkūnas being their guardian. Such Radziwiłł Perkūnas, recent friends, quara tempting piece, and under his nose… reled over her dowry (Chodkiewicz approElżbieta was also interested in the marriage priated something of his under-the-care’s

dowry). Janusz was kicked downstairs in his bride’s house and a war nearly broke out. It is said that the prayers of Sophia, who is now recognized as a saintly saint, helped to resolve the conflict peacefully.

Sophia died without leaving any children, and Solomon Rysinski wrote a very beautiful epitaph on her death.

Through this marriage, after the death of Sophia in 1612 Radziwiłł received Slutsk. Rysinski lived and worked there for a while.. It is known that Janusz set up a Protestant school in Slutsk, and Rysinski made its charter.

Two Krzysztof, two Janusz, one Solomon

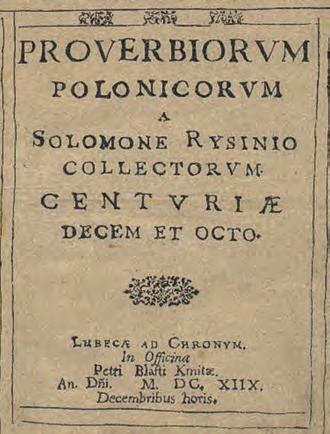

Radziwiłł Reformers opened schools and printing houses… And Rysinski took full advantage of this. In Lubcha he printed a book about the deeds of his lord, Krzysztof Radziwiłł, adding a poetic description of the Livonian war. He published a collection of eulogy poems in which he glorified the actions of the Radziwiłł family. In 1618 he published the world’s first collection of Slavonic proverbs and sayings, 1800 of which he had collected over three decades. He recorded them in Belarusian, translated them into Polish and Latin, searched for their analogues in old Roman and Greek… About half a thousand of those proverbs are still alive in Belarus! Although the title says “Polish”, it is established that Rysinski collected them in the surroundings of Slutsk and Niasvizh. That’s what needs reprinting, translated into modern Belarusian!

In those years when Solomon was writing and publishing books, his guardians were engaged in a war with the Swedes. Perkūnas, having won several glorious battles, died in 1603. Krzysztof Radziwiłł and Janusz showed themselves to be capable military leaders. And Janusz raised a nobleman’s rock against the king.

But in those turbulent times, Solomon Rysinski had one more important thing to do. In 1612 a son Janusz was born in the family of Krzysztof Radziwiłł, Janusz’s younger brother, who was in love with Anna Kiszka. His tutor was also Solomon Rysinski.

We must admit, one can get confused by the names… That’s why sometimes there are statements that Rysinski brought up the son of Krzysztof Radziwiłł Perkūnas Janusz, since his childhood. But we are talking about Perkūnas’ grandson.

Janusz Radziwiłł graduated from the Calvinist Gymnasium in Slutsk, its charter had been made by his teacher, and also went to study to Leipzig and Altdorf universities. But he went abroad at the age of sixteen, a year after Solomon Rysinski’s death.

Janusz, a grandson of Perkūnas, will go down in history as a staunch defender of the idea of independence of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, as the one who exclaimed at the Seim — “The time will come — the Poles will not come to the door: we will throw them out through the windows”, alluding to the events in Prague, where German Catholics were thrown out the windows of the parliament by Czech Protestants. He defended the rights of the non-Catholic population, formed an alliance with the Swedish king in the hope of establishing an independent principality, and died, having been poisoned and declared a traitor.

Nothing but books

Apparently the philosopher poet did not have a family of his own. And despite all his scholarliness, he did not gain any special favours. It is interesting that at the same time Rysinski is almost the only thinker of that time, who remained secular. A testimony of the poet’s death in 1625 in the village of Delyatichi in the Novogrudok District has survived: “On the first Thursday after St. Martin, in the afternoon, when he was sitting at the table, paralysis took him and his tongue was caught. Then at night he had a hard kaduk forty times. He did not lose his memory or his vision, which was clear from his gestures when he was reminded by priest Romanowski, who allowed him to be strengthened in faith and hope and about different things. He drank different water, he could not swallow more on Sunday evening and still he had a kaduk, though not so hard and not so thick until his death. And on Monday at dawn on Tuesday at six o’clock in the presence of landlord Naborowski and priest Romanowski, who gave prayers, and with other young people he fell asleep in the Lord, quietly, after groaning heavily.”

The first man who called himself a Belarusian was buried in Lubcha. His pupil Krzysztof Radziwiłł ordered to “erect a

ZVIAZDA.BY

The first Belarusian Solomon Rysinski wrote over a thousand books

high and nice stone pillar over Pan Rysinski ‘s grave and to set a marble table in it, and to build a nice mound at the back near the pillar”. The only wealth left after Rysinski’s death was books. However, they say there were more than a thousand of them, rare editions and manuscripts, and the library was comparable in importance with the Royal one.

The researcher Evgeny Poretsky writes: “Creative heritage of S. Rysinski, who from humanist-commentator and researcher of antique literature and teacher of ancient languages was able to rise to the heights of humanism, i.e. to find the sources of wisdom in the folk language of his native land, has not been studied until recently… To analyze Rysinski’s work today and to publish his works is to bring back to Belarus one of the authors of the high cultural monuments of the past”. By Lyudmila Rublevskaya