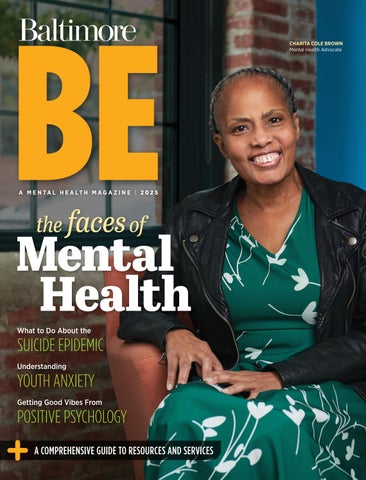

Mental Health the faces of

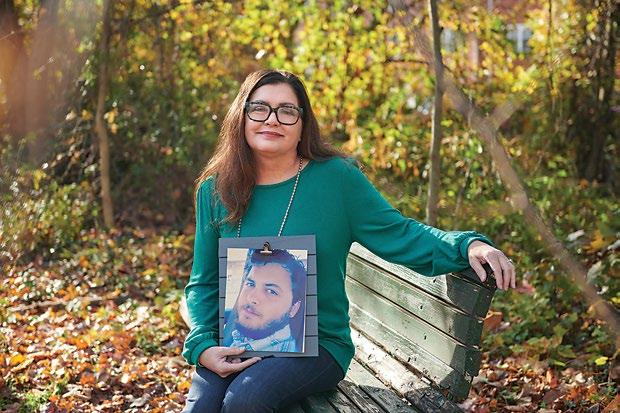

CHARITA COLE BROWN Mental Health Advocate

Sheppard Pratt is the largest private, nonprofit provider of mental health, substance use, developmental disability, special education, and social services in the country, and is consistently recognized as a top national psychiatric hospital by U.S. News & World Report .

With more than 160 programs, spanning inpatient, outpatient, communities, residential, and schools, Sheppard Pratt is here to help.

At Hygea Healthcare, we provide innovative addiction treatments that combine traditional methods with cutting-edge technology and alternative healing approaches. Our team of professionals—including doctors, nurses, licensed clinicians, certified therapists, and peer support specialists—offers a comprehensive range of CARF-accredited levels of care. We provide detox, inpatient and outpatient services, and recovery aftercare, meeting clients wherever they are in their recovery journey.

HYGEA

ON THE COVER Author and advocate Charita Cole Brown reflects on living with bipolar disorder in our “Faces of Mental Health” feature. Photography by Joanna Tillman.

32 Lifeline

We look at the rising number of deaths by suicide in the U.S. and how can they be prevented. BY CHRISTIANNA MCCAUSLAND

38 The Faces of Mental Health

Seven Baltimoreans speak out about how mental illness has touched their lives. BY JANE MARION, CHRISTIANNA MCCAUSLAND, AND MAX WEISS

➜ ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: READ OUR COMPLETE CONVERSATION WITH LT. GOV. ARUNA MILLER.

DEPARTMENTS

Kids Are Not Alright

Unpacking the surge in youth anxiety.

BY LAURA FARMER

Good Vibes

How positive psychology uses human strengths to build happiness, gratitude, and resilience.

BY DAN COOK

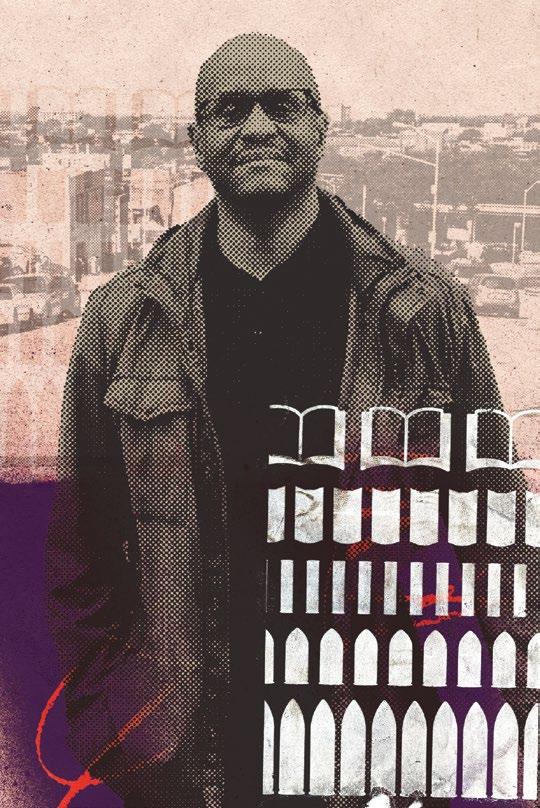

The Journey to Healing

A first-person perspective on trauma in Baltimore and the importance of accessible counseling.

BY KEVIN SHIRD

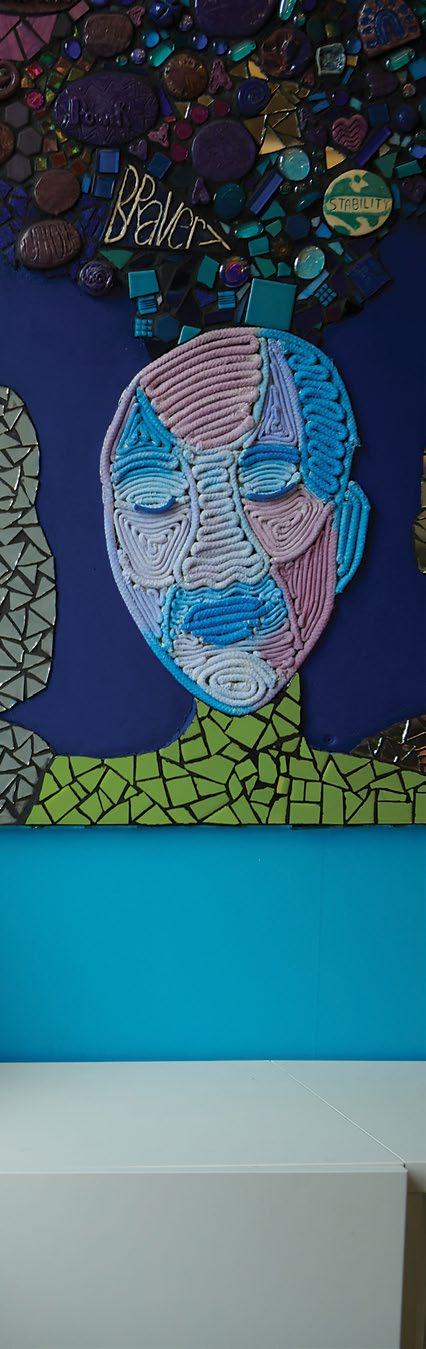

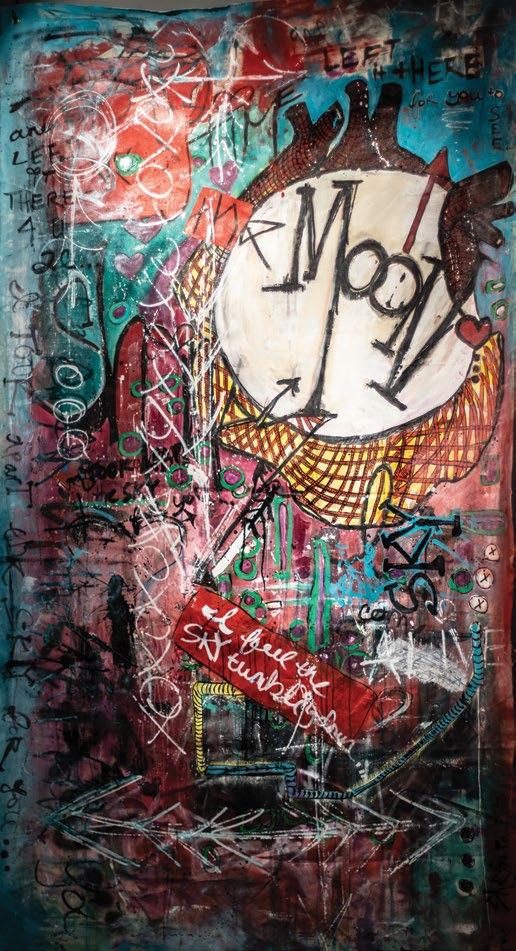

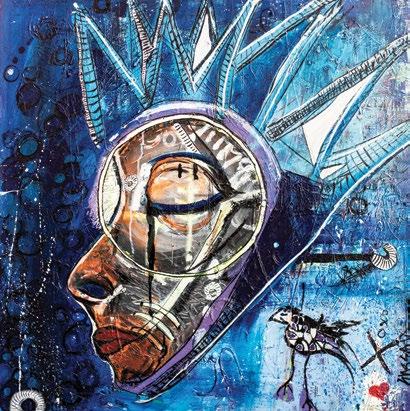

BLANK CANVAS

Nicole Clark

A local artist finds healing through her practice. BY JANE MARION

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: SEE THE ARTIST AT WORK.

The

The renowned psychologist and author of An Unquiet Mind speaks out.

BY JANE MARION

How Be Came to Be

The topic of mental health is deeply personal to me and my family. Over 17 years ago, the youngest of my three sons presented with mental health challenges. He was 16 at the time, and until then was a straight-A student, a gifted athlete, talented musician, and had lots of friends. In other words, he was living a good life . . . as were we as a family.

My wife and I were totally caught off-guard, so I can only imagine what my son was going through. We immediately got him the help he needed through therapists and psychiatrists. At the same time, we had to fast-track our learning because we were clueless about his mental health condition. We also realized the need for emotional support, because while our friends had the best of intentions, they couldn’t possibly know what it was like to have a child struggling with a mental health diagnosis. How could they?

In our search for answers, we discovered NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) Baltimore and attended a family support group. From there we learned about NAMI’s Family to Family program and attended their 10-week course. This taught us about the science behind mental health conditions, and the ways to best support our son. Just as importantly, it gave us the tools we needed to cope with his condition.

While much has changed since our son’s diagnosis, a needle that hasn’t moved quite as far as we might like is that of the stigma related to mental health conditions. Individuals with mental health diagnoses still face discrimination; they and their loved ones still deal with shame and blame. The concept of Be is to use storytelling to increase awareness and empathy for those affected by mental illness. In doing so, our aim is to reduce stigma and inspire acceptance and understanding.

NAMI had a profound and positive impact on my family and, 17 years later, I’m honored to continue volunteering as a family support group facilitator and advisory board member following many years of serving as their board chair. That is why, when we decided to move forward with this publication and corresponding event, it was natural to make them our nonprofit partner.

None of this would have happened without the support of CareFirst Blue Cross Blue Shield. From the very beginning, they pledged meaningful support to this ambitious ini tiative, which enabled

We hope you benefit from reading this publication. Our next step is to bring it to life with a storytelling event taking place in collaboration with Stoop Storytelling on March 6. For more information on the event, you can check out

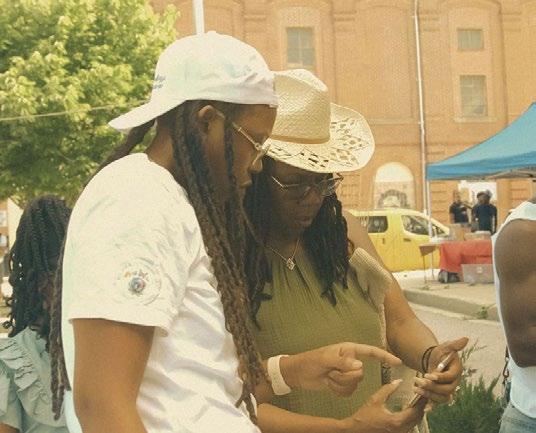

Drawing on his own lived experiences, he supports 12to 18-year-olds facing mental health challenges in an afterschool program. His journey is a reminder of the powerful impact of treatment, empathy, and understanding in mental health recovery.

Michael Teitelbaum President, Baltimore magazine

Sam, here with his father Michael, works as a certified peer recovery specialist.

TRANSFORMING TRAUMA INTO STRENGTH

For over 23 years, the Holistic Life Foundation (HLF)—a Baltimore-based, BIPOC-led nonprofit founded by Ali Smith, Atman Smith, and Andres Gonzalez—has been at the forefront of trauma-informed yoga and mindfulness education. Our groundbreaking programs have empowered over 200,000 students and adults through 100,000+ hours of mindfulness training in schools, detention centers, drug treatment facilities, and underserved communities worldwide.

WHY THIS PROGRAM?

A pilot trial conducted with Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health , Penn State , and Baltimore School District found that HLF’s mindfulness programs enhance emotional regulation, reduce stress, and improve resilience—findings published in the Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology Kennedy Krieger studies further recognize their impact in addressing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and community trauma healing.

HLF was a driving force behind the trauma informed yoga and mindfulness framework of Baltimore’s Healing Cities Act, helping to establish the nation’s first trauma-informed city. With programs supporting trauma healing across five continents, HLF is recognized as a leader in trauma-informed yoga and mindfulness. As a certified instructor, you’ll gain mentorship, professional development, and access to a global network, expanding your impact and career opportunities.

Our 400-hour training program includes an in-person retreat in Baltimore with interactive online modules, covering yoga, meditation, breathwork, and traumainformed teaching. Gain real-world experience, hands-on mentorship, and the tools to create lasting impact in your community.

Stephen A. Geppi

Vice President Finance and Operations Debbie Darmofal

EDITORIAL, ART & PRODUCTION

Christianna McCausland

Senior Advertising & Marketing Designer Emily

Dan Cook, Laura Farmer,

Contributing Photographers and Artists Tracey Brown, Nicole Clark, Anthony Grant, Joanna Tillman

Vice President of Sales Stephanie Shapiro

Senior Account Executives Michelle A. Coughlan, Danny Glazer, Jodi Hammerschlag, Jennifer Rosenberger

Account Manager Michelle Weinstein

MARKETING

Director of Marketing Lorann Cocca

Content Marketing Manager Kamilia Arroyo

EVENTS

Events Director Jackie Hershfeld

DIGITAL

Digital Senior Editor Lauren Cohen

Digital Operations Manager Megan McGaha

BUSINESS

Finance Consultant Zach Papesh

ADVERTISING/EDITORIAL/BUSINESS OFFICES 10150 York Rd., Suite 300, Cockeysville, MD 21030 443-873-3900 baltimoremagazine.com

HIGHEST SELF

SERVICES WE OFFER:

Individual, Couples and Family Counseling

Medication Management

Psychiatric Rehabilitation Program (PRP)

Respite

Community Housing

Partial Hospitalization

Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP)

Residential Treatment

Community Employment Services

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT)

Day Treatment

Reiki Energy Healing

OUR

D-Dedication

I-Improvement

V-Vulnerability

I-Integrity

N-Neighborly

E-Example

LOCATIONS:

To live in Baltimore is to love it. To love something

is to watch it change and grow.

In a world where mental health care can be challenging to come by – whether due to stigma, providers outside of your insurance plan, or simply the overwhelming lack of available mental health care providers – knowing what resources are available is key. Luckily, Baltimore is famous for being a city of neighborhoods. And as neighbors, we hold an unspoken agreement to show up for one another. Whether it’s at a block party, a front stoop, the neighborhood community center, the corner bar, or a weekly support group, there’s no shortage of people who care.

That’s the thing I’ve always loved best about living here–and the thing I love most about NAMI Metropolitan Baltimore. We’re an organization built by people who, back in 1983, were looking for support and didn’t have somewhere to turn, so they made one. This effort that started as a conversation around a kitchen table has since blossomed into the nation’s largest grassroots mental health organization, made up of real people on the ground, all over the country, who understand their immediate community’s unique needs.

Here are the facts: People in Baltimore experience Adverse Childhood Experiences at a higher rate than the rest of Maryland, the average delay between the onset of mental health symptoms and treatment is 11 years, and one major reason for this delay is stigma. That’s why it matters that over 200 of your neighbors volunteer with NAMI Metro. To help the 1 in 4 of us who will experience a mental health crisis in our lifetime and the people who love them.

How do we do that? By intentionally holding spaces where we can explore our emotions without judgment; by bringing mental health education into where we learn and where we worship and where we work; and by boldly sharing our stories so others can share theirs. Let’s normalize the conversation about mental health and eradicate the stigma that keeps so many of us from seeking help. Mental health isn’t someone else’s problem–it’s yours and mine, and Baltimore’s, together. We can all contribute to making a difference.

Kerry Graves, Executive Director

Mind Matters

BRAIN AIDS

These innovative treatments may offer alternatives to those for whom conventional therapy is not effective.

➜

BY COREY MCLAUGHLIN

NEW FRONTIERS

An estimated 60 million Americans experienced a mental-health related illness in the past year, and some researchers believe roughly half of the U.S. population will encounter one at least some time in their life. For many, traditional front-line treatments like talk therapy and medications such as antidepressants–which have been found to help roughly two-thirds of the population–are effective. But for others, alternative options have been limited until recently.

Some treatments are newer than others. Psychedelics, for example, are ancient but remain taboo in many circles. Much like the brain itself, many are just starting to be understood. “We can take pictures and try to measure some things, but the brain is a little harder to study than other areas of the body, because it’s obviously inside of our skull and it’s hard to access,” says Trish Carlson, a psychiatrist at Sheppard Pratt.

The following innovative treatments, practiced and researched locally, show promise to help meet the challenge.

IT’S ELECTRIC

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is a non-invasive, in-office potential solution for treatment-resistant depression.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS, can be a relatively simple, life-changing choice for those with treatment-resistant depression. (Patients who qualify have tried at least two antidepressants that have not proven effective.)

Transcranial means across or through the skull. With TMS, a magnetic coil is positioned over the head that delivers electrical pulses one to two centimeters deep, usually to stimulate a part of the left side of the brain (the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex) that’s been found to be underactive in people with depression.

So long as patients don’t have epilepsy or seizure disorder or metal in the head or neck, the treatment is considered safe and delivered under the guidance of a doctor, nurse, or trained technician. Patients sit in a chair for roughly 20 minutes a day, five days a week, for five or six weeks, and let the machine work. There’s a three-minute protocol that’s also effective.

Trust the Process

Eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing, or EMDR, can calm the brain to help you make sense of trauma, anxiety, and stress.

A black plastic bar, about to be illuminated with green dots, rests on a tripod a few feet away. You’re handed a pair of mouse-sized buzzers, told to think of your distressing thought and follow a speck of light as it moves from left to right and back again. The buzzers occasionally stimulate your hands.

The sequence moves quickly. It can be difficult to keep up. After 10 seconds or so, a clinician pauses everything, asks you to briefly share what you’re thinking now, if you’re still stressed at a level 10. Repeat. Again. For up to an hour, or maybe even another session, until you report you’re feeling closer to zero—calm—while thinking of what’s been bothering you.

“What it’s thought to do, in the same way that we think oral medications work, is change the neurotransmitter balance in the brain,” says Trish Carlson, a psychiatrist and service chief of the TMS program at Sheppard Pratt in Towson. She notes that everything in our brain works

off electrical energy. “TMS is focusing directly on the area of the brain we think needs to be rebalanced.”

The noninvasive procedure is thought to rebalance neurotransmitters in the brain like serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, that help to regulate mood, and increase blood flow in the targeted area.

The FDA approved TMS as a major depression treatment in 2008 and Carlson says the majority of people will see some improvement. Research shows that roughly one in four patients experience full remission and about half enjoy partial relief, with about two-thirds still feeling better a year later.

Most insurances cover TMS use for depression. In 2018, the FDA also approved it for treating obsessive-compulsive disorder by way of targeting a circuit across both sides of the brain while a patient is asked to think of, or be exposed to, what makes them anxious. More research is being done relative to cognitive disorders, addiction, and PTSD.

This is what eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing, or EMDR, looks like at Bolton Therapy & Wellness in Bolton Hill, one place you can find the mental health treatment technique that can help heal trauma or other troubling experiences. The process, which can include tapping opposite sides of the body or listening to sounds, mimics natural dual attention (or bilateral) stimulation in the body thought to help the brain properly store and process distressing memories.

The eye movement and other stimuli are “calming the right brain that’s feeling the anxiousness and bringing onboard the left brain that’s reasonable,” says Lisa Robinson, the practice director at Bolton. “At the end, you don’t have the same agitation, physical sensations, or arousal due to the memory, and you can move on.”

Developed in the late 1980s by New York-based psychologist Dr. Francine Shapiro, who found that walking paired with moving her eyes back and forth eased her distress, EMDR has since been found to help

Reality Shift

people cope with PTSD, anxiety, stress, phobias, addiction, and to rewire memory networks in adults and children.

“It’s changed my practice,” says Dr. Desyree Dixon, who founded Bolton in 2013, got trained in EMDR in 2019, and now teaches others to use the method. “Sometimes I want to reach out to some of my earlier clients and say, ‘Come back, let’s work on some of these things using this new tool.’”

Psychedelics still have limited legal use for mental health, but that could be changing.

You don’t need to travel far to realize Baltimore is an epicenter of psychedelic research. Johns Hopkins Hospital has a research center that’s been dedicated to psychedelics for the last two decades and at Sheppard Pratt, the Institute for psilocybin has been exploring uses since 2022. And beyond those institutions, there’s a local community exploring the potential mental health benefits of psychedelics’ mindaltering power.

David Jun Selleh, a psychotherapist and licensed clinical professional counselor at Inner Path Wellness in Mt. Washington, for instance, is a part of Maryland Gov. Wes Moore’s task force—established in 2024 as the seventh of its kind in the U.S.—due to deliver policy recommendations for psychedelics from mushrooms and plants to state legislators by the end of July. “Generally, all psychedelics induce neuroplasticity in the brain,” Selleh explains, “the growth of new cells—which allows for new ways of thinking and new perspectives. When you combine that with [talk] therapy, it breaks everything open to possibilities.”

He’s sitting on a couch at Inner Path, alongside University of Maryland, Baltimore alumna Lauren Going, who co-founded the city’s first psychedelicassisted therapy center in 2022. Here patients are given an eye mask, headphones, a mat, and a private room to sustain them on their travels, and as soon as four minutes after receiving

a supervised injection of the psychedelic drug ketamine, they usually experience the peak of what’s typically a 45-minute to hour-long “journey,” says Selleh.

It’s a hallucinogenic trip often described as an out-of-body experience. Ketamine, primarily a synthetic drug used legally for decades as a general anesthetic, creates a surge of the neurotransmitter glutamate in the brain. At Inner Path, ketamine is used off-label for treatment-resistant depression, suicidality, or other mental health disorders. With a low psycholytic dose, people can think and speak clearly while they’re under the influence. With a higher dose, after patients return to reality, a second hour of talk therapy follows, the idea being the trip can spur more lasting change.

Times and tastes have changed since the heyday of the Grateful Dead and in the roughly 50 years since most psychedelics were outlawed by President Richard Nixon in what became known as the War on Drugs. Names like “magic mushrooms,” (psilocybin), LSD, or MDMA still get a bad reputation. Ketamine is also still known as the “Special K” party drug. But psychedelics, which some archeologists say humans may have experienced tens of thousands of years ago, delivered in a supervised clinical setting have shown great promise.

In 2019, the FDA approved a ketamine nasal spray for major depression. The Department of Defense is funding psychedelic research for veterans with PTSD and traumatic brain injury. Additional legal pathways for uses could be coming. The 19-member state task force of which Selleh is a part won’t directly change the regulatory status of any psychedelics, but their recommendations could be a catalyst. “There is rising support,” Selleh says. “People are hearing enough to know there’s something to this.”

Kay Redfield Jamison A CONVERSATION WITH

The renowned psychologist and author of An Unquiet Mind talks about stigma.

BY JANE MARION | PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARLAYNA DEMOND

As a young girl growing up in Virginia, Kay Jamison was intense, curious, and had a keen fascination with science. She volunteered as a nurse’s aide, a candy striper, and even assisted with minor surgical procedures at the hospital at Andrews Air Force Base, where her father was a pilot and meteorologist. At 15, she toured a federal psychiatric hospital, St. Elizabeths in the District of Columbia, for the first time, which she says she found “fascinating and horrifying,” not knowing that she, too, would soon suffer from own mental illness.

And while Jamison had always had a passionate personality, by the time she was a senior at Pacific Palisades High School in suburban Los Angeles, she found her moods shifting between two extremes—exhilarating highs and dark, unyielding lows. That pattern continued for years, though she never sought help or intervention.

It wasn’t until 1974 (just three months after becoming an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles) when she became, in her words, so “ravingly psychotic” that she could no longer ignore the fact that something was terribly wrong. That something was bipolar illness, then known as manic depression. It was, in fact, a disease she was all too familiar with thanks to her patients whom she diagnosed (and her own father who struggled with the

illness). And though she shared her diagnosis with colleagues and close friends, her illness was largely a secret.

After years of serious struggle, a near-lethal suicide attempt, and always a fear of being “discovered,” in 1995, Jamison wrote An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness, an astonishing account of what it’s like to live with bipolar illness. As both a student of the disease and someone who struggled with it, the stakes could not have been higher.

immune from detractors. As she writes in a 2011 preface to An Unquiet Mind, 15 years after the book’s first printing, “The kindness and generosity of most people was heartening, the vitriol and irrationality from others disturbing.”

Because she was afraid of the way her work would be perceived, Jamison knew that telling her truth would mean giving up her clinical practice, by then at The Johns Hopkins Hospital. She also feared that publicly sharing her story would lead to losing her hospital privileges or, even worse, her medical license.

It did not. Instead, she revolutionized the field, becoming one of the most famous faces of the illness (along with a long line of luminaries who suffered from bipolar disorder, including writer Sylvia Plath, poet Robert Lowell, and composer Gustav Mahler) and one of the foremost authorities in the world on the disorder, even co-authoring the definitive medical text on the topic.

The acclaim, however, has not made her

Thirty years since the publication of her groundbreaking book, we spoke with Jamison (now professor of psychiatry at The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and co-director of the Johns Hopkins Mood Disorders Center) about stigma, how to prevent it, and how views about mental illness have changed since she wrote her memoir.

Do you remember the day you were diagnosed with bipolar illness, which was then known as manic depression? I went to a psychiatrist who had been my clinical supervisor when I was an intern and I trusted him implicitly as a doctor. He was the only one I trusted to go see and he just gave me a very thorough psychiatric examination. He said, “It’s unequivocal. You have manicdepressive illness. You are going to need to be

on lithium”—and that was the beginning of struggling with that notion of taking lithium. Overwhelmingly, I was relieved because I knew he was right and I admired him for not mousing around about it and not prettying it up and just saying, “This is going to be really hard.”

Was there a light-bulb moment when you decided to write An Unquiet Mind?

Some of it was that I felt hypocritical treating and studying the illness and not acknowledging that I had it. Also, I got fed up, hurt, and overwhelmed by the lack of information about how many people have bipolar illness and how unaware the world is in general.

When did you start thinking about the impact of sharing your story?

All along, and certainly when I was going to publish a book about my illness, I thought about it endlessly. Would I lose my job?

Would I lose my hospital license? Would I lose my state license? I knew I would lose my privacy and I knew I would lose my ability to see patients.

Was any part of you reluctant to share?

Of course—and I still am. I am trained to be a therapist and I loved it. It was a huge part of my clinical identity. I practiced close to 20 years, including clinical training before giving it up.

Why did you feel you’d lose the privilege of seeing patients for sharing your story?

I had written a very personal book. I had practiced before [the book was written] and had told people about my illness and also colleagues with whom I’d worked to feel free to contact my psychiatrist and chief of my department if there were any concerns whatsoever. Fortunately, that didn’t happen. My book was terribly personal and I think patients have a right to come into your office and talk about their own problems without putting it through the whole kind of strange way of looking at it from someone who has written a book about it.

Where does stigma come from?

“Stigma” is a word I really don’t like, I prefer the word “discrimination,” partly because it has legal implications but one uses stigma because it’s widely used.

So where does discrimination come from?

If you look at the animal world in general, whether you look at a dolphin or a sea lion who is strange to a group, that will be picked up immediately—and the animals will respond accordingly. It’s a natural reaction when things are different. It’s not surprising that when people act in ways that are not usual or ways that make people frightened or hopeless, people are going to distance themselves from it. I feel very strongly where our field [of medicine] has let all of us down is that you can’t just expect people to understand—that is unreasonable. What you can do is give them information with which to possibly change their mind.

How do you prevent discrimination?

The greatest way to destigmatize any illness, and particularly with a psychiatric illness, is with research and good treatment. If you look around you in medicine and you look at epilepsy, for example, it’s not that there’s not still stigma around it but there’s much less stigma than there used to be. And that started when you could begin to control public seizures. And with something like cancer in the ’50s, when it was pretty much a death sentence for many kinds of cancers, people wouldn’t talk about it—and now it’s treatable, so they talk about it much more.

What is the impact of stigma?

The most devasting impact is that people don’t get treatment. They feel alone with their suffering and they feel like they don’t want to reach out and others don’t understand or their licenses are going to be pulled or they are going to lose a job or a relationship—and those are all very legitimate reasons. And then, of course, people stigmatize themselves by saying, “I should be able to pull myself together.” This seems much more a

part of personality than other medical illnesses. It seems like you ought to be able to get over it by dint of will.

When you got sick, was your line of thinking that you should “just be able to handle it”?

At some point it became clear I was ill and that I was not anywhere near myself. It took a while. I was brought up like many people to believe that you could just get a grip—I was brought up Episcopalian and in a military family and in worlds that put a real premium on coping with something yourself and getting on with it. And that’s completely not helpful. It’s a good philosophy of life in general, it’s just not a good philosophy of life when you are ill.

Do you see things changing in terms of discrimination?

I do. The things that have helped psychiatric illnesses is that there are many more treatments available than there used to be. And people are much more aware of it than they used to be. General physicians are more aware of it, too. And people in general are aware that there are antidepressants and you can go to a doctor and maybe get some help. People talk about it more. And thanks to the internet, people can learn much more about it.

People are better informed than they used to be, but I also think there’s a huge amount of misinformation and a lot of terrible attitudes. If you look at the language in the public arena in politics, you can say people are “crazy,” “come from insane asylums,” or are “nutty as a fruitcake.” People can say things about those with mental illness that you could never say about any other large group. That’s painful for people.

How did the pandemic impact people who were struggling?

One of the things that happened during the pandemic is that people became much more aware of the extent of mental illness around them, because they were in day-to-day contact with their kids in a way in which they

are ordinarily not—so they saw the illness. But it has also had a tendency, perhaps, to trivialize—everything is “anxiety” and “depression” in a general, somewhat ill-defined way. There’s all these sloshing around of concepts together that take away from the notion of illness. People say, “mental health issues” instead of mental illness. I suppose it’s meant to be less stigmatizing and more normalizing. But it’s confusing. I just think that the language has gotten mushy.

You were diagnosed as a medical resident. How have you seen attitudes toward seeking help change within the medical community? Residency programs are doing better than they used to and are more aware of depression and stress. It’s up to medical students and medical school faculty to make education about depression a priority so that students recognize symptoms if they get them—or can recognize them in their colleagues. It’s better now than it was, but it’s still pretty minimal.

Your memoir was published 30 years ago. Would you do anything differently now?

Probably not—you have to write what you have in front of you in terms of your life. You are not given the opportunity to go back and change things.

What advice would you give to your younger self and what do wish you knew then?

I went off my medication on and off for the first few years of my illness but that was very costly, there was tremendous loss, and I haven’t stopped my medication for decades, but I regret that hugely.

What personal price did you pay for going off your medication?

Getting manic, getting depressed again, getting suicidal, nearly dying by suicide.

What’s your advice to anyone who is struggling or who loves someone who is? Learn. Read. Be aware that good treatment exists and that the consequences of not getting treatment are pretty awful.

RESIDENTIAL MENTAL HEALTH TREATMENT PROGRAM FOR YOUNG ADULTS

ClearView Communities is a longer-term (12-18 months on average) residential mental health treatment program located in the suburbs of Frederick, MD treating young adults. Our program incorporates four houses on campus, with eight private bedrooms in each.

PSYCHIATRY & MEDICATION MANAGEMENT

INDIVIDUAL, GROUP & FAMILY THERAPY

4 HOUSES, 32 BEDS STAFFED RESIDENCES

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY

ART STUDIO & EXPRESSIVE THERAPY

THERAPUTIC NATURE PROGRAM & GREENHOUSE

WELLNESS CENTER

MILIEU THERAPY & SOCIAL SKILLS

INDEPENDENT LIVING & DAILY LIFE SKILLS

COMPREHENSIVE NURSING CARE

COMMUNITY INTEGRATION INCLUDING SUPPORTED EMPLOYMENT, EDUCATION & VOLUNTEERING

The Kids Are Not Alright

What’s behind the surge in youth anxiety?

Lindsey Culli vividly remembers the day in the fall of 2021 when she got a phone call from the counselor at her son’s Baltimore County public school alerting her that he had expressed a desire for self-harm. At the time, Calvin was a six-year-old first grader who was struggling to navigate the post-pandemic world, especially after spending his early education in front of screens.

“Calvin was one of those kids who was in kindergarten when the pandemic started,” Culli recalls. Though her son was academically high achieving, she believes that the social isolation of those years stunted his social and emotional growth.

“He’s an introverted kid. He was feeling all these big feelings [at school] and he didn’t have a way to express it,” says Culli. “He was saying the most outrageous thing he could say, which terrified the guidance counselor because he started talking about self-harm.”

Naturally, this alarmed his school counselor, who took his words seriously. Thankfully, it eventually became clear that Calvin didn’t have plans to actually harm himself.

“He was just kind of grasping at, ‘What is the biggest thing I can say to get somebody to pay attention because I’m not okay. I don’t know the language to talk about what’s wrong. I just know that something is.’”

Eventually, Calvin’s “big feelings” escalated to a point that Culli and Sam, Calvin’s father, decided it was time to seek professional help. Fortunately, Calvin’s school had an arrangement with a private practice therapy group that saw students during the day. His therapist diagnosed him with anxiety and began helping him learn tools to manage it.

“He started seeing a therapist that spring and it was really helpful pretty much right away,” says Culli. “[His therapist] gave him the toolbox that he needed and started putting tools in his toolbox to be able to recognize the emotions he was feeling and name them [and] work through them. That is hard when you’re an adult, but it’s especially hard when you’re only six! He’s come a really long way and it’s a testament to the therapy that he’s gotten and the people that he’s been able to work with.”

Today, Calvin is an active 10-year-old. He still struggles with anxiety—Culli thinks it is likely part of his wiring as someone who strives to be high-achieving. The difference is, when he gets those “big feelings,” he knows how to process them. Best of all, Culli has watched Calvin grow into the creative, empathetic, and thriving kid she always knew him to be.

“We named Calvin after the [comic strip] Calvin and Hobbes,” says Culli. “It turns out he’s actually a lot like the comic book Calvin! He’s very creative. He’s very bright. He’s also a really good friend. He has so much empathy, which probably hinders his mental health a little bit because he takes on other people’s feelings and emotions. I think it’s both a strength and also a challenge to be an empathetic and compassionate person in a world that can be so tough. But now he has the tools to manage it.”

Calvin’s experience with anxiety as a young child is not unique. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 10 percent of children between the ages of three and 17 have a diagnosed anxiety disorder. Experts contend that it’s normal for kids to experience occasional anxiety about stressful things like academics or social situations. But the National Institutes of Health (NIH) explains that anxiety becomes a disorder when it does not go away and its symptoms interfere with daily activities.

Biologically, the way our bodies experience anxiety is similar to the way we process fear. Fear keeps us safe from danger, preparing our bodies for “fight or flight.” Our heart and breathing quicken to boost oxygen flow to our brain. Our muscles tense up to prepare us to run, fight, or hide. Our minds zoom in with a laser focus on the threat to determine the best plan for safety. Anxiety is the body’s response to a perceived threat. While this heightened state of awareness is helpful for actual danger, living in a state of high alert about unspecific future threats can be overwhelming—especially for children who may not have the tools to manage these feelings.

Krista Dhruv, LCSW-C, is an individual and family therapist and educational consultant based in Baltimore. She has served as a counselor in K-12 schools and higher education settings and has observed how anxiety presents in children of all different ages.

“Starting with our youngest kids, they might experience somatic symptoms, like belly aches, headaches, and disrupted sleep,” explains Dhruv. “It manifests physically because anxiety is in the body. It’s hormonal—cortisol and adrenaline, a hormonal response to perceived fear, metabolizes in the body. [Anxiety] also shows up as worry language: a lot of ‘what ifs’—‘What if you forget to pick me up? What if nobody wants to play with me? What if I eat something and it makes me sick?’”

Research suggests that the causes of childhood anxiety are complex. Some children may be more sensitive to strong emotions or have a biological tendency toward anxiety. For others, anxiety may develop as a reaction to a significant stressful event, like a death in the family. Environmental stressors, such as food insecurity, parents who fight or argue, or experiences of bullying, abuse, and neglect can also cause anxiety in young people.

Further, larger events and issues, such as climate change or global instability, may also impact children’s wellness—especially for older kids who may be more aware. An often-cited study conducted by the Pew Research Center indicates that more than half of teenagers are worried about a shooting happening at their school. Other environmental factors inducing

worry are, well, the environment. A recent survey published in The Lancet polled 10,000 young people across 10 countries, revealing that as many as 84 percent of respondents were worried about climate change, with 45 percent reporting that climate anxiety affected their daily lives.

Regardless of the constellation of causes behind anxiety, it is important to note that it is on the rise. A Department of Health and Human Resources report in 2022 noted that between 2016 and 2020, the number of children ages 3-17 years diagnosed with anxiety grew by 29 percent and those with depression by 27 percent. This is important on many levels, not least of which is that a mental health

“overprotection in the real world and underprotection in the virtual world are the major reasons why children born after 1995 became the anxious generation.”

Kids’ brains are literally being rewired during their crucial early, brain-building years.

“In this new phone-based childhood, free play, attunement, and local models for social learning are replaced by screen time, asynchronous [or non-real-time] interaction, and influencers chosen by algorithms. Children are, in a sense, deprived of childhood,” explains Haidt.

Dhruv agrees and has observed the impact of screen time on today’s youth.

“[Social media] is kind of experience where young people are socializing and interacting,

Anxiety can show up as what ifs: ‘What if you forget to pick me up?’ ‘What if nobody wants to play with me?’

condition is a risk factor for suicide, which is also on the rise among young people. Increasingly, experts point to a growing cause of mental illness in young people: social media and phone use. Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist and author of The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, claims that what he terms a “phone-based childhood” is to blame for a many of these unsettling youth mental health trends. In fact, so great is the impact of social media that U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy recently called on Congress to require warning labels on social media sites to communicate their potential harms, especially for the developing adolescent brain. And Australia just passed a groundbreaking ban on a social media for children 16 and under.

Haidt likens young people’s unrestrained exploration of this new virtual frontier to launching our children to the planet Mars without first doing an appropriate amount of research to realize their bodies and minds are not suited to survive this alternate planet. The research he presents in his book posits that

but being that they’re online, the whole body isn’t involved—it’s disembodied. Young children aren’t outside as much playing and climbing trees—maybe even spraining an ankle. Kids aren’t taking healthy risks, which are imperative to healthy development.”

“These are normative life experiences that build our resilience and develop a growth mindset,” Dhruv continues. “When most of our [socializing and recreation] is happening online, whether it is video games or through social influencers, we lose that ability to take risks, social or physical or emotional, and to really experience failure as well as success, which is part of life.” She echoes Haidt’s ideas about asynchronous interactions: “I might text you this morning about a funny thing that my dog did and you might not text me back until 3 o’clock today with a cute little emoji, which feels good.” But something is off: Human beings aren’t meant to communicate via delayed reaction or strictly through our laptops or phones. “We are wired to be in community and in connection,” she says. “We should be able to read body language. If I say something and a friend grimaces, I realize I probably shouldn’t

say that again, or I should check in with her about that. [With online socializing], we lose all that nuance of the human experience.”

There is, however, a silver lining to the over-sharing that is often seen on social media. Experts note that children are increasingly likely to talk about their mental health with transparency, which is steadily chipping away at the stigma of mental illness. There are additional benefits to phone use and social media. For example, many kids who may feel marginalized due to their differences can more easily find their community online. And experts are keen to note that the phone itself is not the enemy: If used responsibly, it’s a valuable tool to help us connect and make life easier. The key is to make sure parents place limits on the amount of time kids spend on screens and the content they view.

“The one positive about social media is that it allows access for a great deal more information,” explains Chad Lennon, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist for Sheppard Pratt. “People are communicating more about their mental health.”

Young people are more aware of mental illness—and the resources available to help.

“What has happened over the past 10, maybe 15, years or so is a complete shift. Now what we see that most of the people coming to us for services, whether it’s in a school environment or private practice, are already coming with the diagnostic language. They’re coming with deep attunement to their emotional experience, saying specifically, ‘I have anxiety,’ or ‘I think I’m neurodivergent,’ or ‘I’ve had this many years of treatment,’” shares Dhruv.

And therapy really does help. Calvin is a perfect example. The tools his therapist gave him were the key ingredients for helping him return to the thriving and intelligent kid his parents knew him to be.

“I think therapy is very helpful for everyone, but if you have anxiety, without [therapy], it can be hard to go through daily life and not get overwhelmed or upset,” says Calvin, with a thoughtfulness and maturity that belies his years. “Therapy has helped me to be able to be in certain places or spaces and without feeling afraid or anxious. I have more friends

now and I can do things I think would be fun without being overwhelmed or afraid.”

For parents of children with anxiety, sometimes it’s hard to know what they can do to help. Lennon advises the following game plan: “First, parents really need to know themselves. The best way to help your own child is if you have a sense of your own emotional regulation,” he says.

“Secondly, I’m really big on helping kids develop coping skills—and I use that term very generally because really anything can be a coping skill, as long as you know it helps you reduce your anxiety. Coping skills can be anything from playing a sport, going for a walk, taking a deep breath, reading or drawing, connecting with friends, even video games can be helpful, if used properly.

“[Thirdly,] connect with someone you trust,” shares Lennon, who adds that this doesn’t necessarily need to be a therapist. “This could be a parent, aunt, uncle, or coach. Helping a child connect to someone they trust helps them realize they are not alone, which goes a long way toward reducing anxiety.”

Therapist Krista Dhruv also advises that a great starting point for finding help for school-aged children is the school counselor and/or pediatrician. “The school counselor is a great first place to go,” she says. “They don’t necessarily know your child best, but they know this age range really well and can help you understand this developmental stage and what’s normative, typical, or atypical behavior.”

The family’s pediatrician is also trained to spot an anxiety disorder or help a family understand how to best help a child. Furthermore, they can examine if there is a physical cause for anxiety, especially when a child presents with somatic complaints. Finally, there’s a practical consideration for reaching out to the pediatrician: They can provide a referral for mental health services, which in many cases makes it easier for your health insurance to defray these expenses.

Fortunately, experts agree that most children with anxiety can reduce its impact through a combination of therapy, appropriate medication, and lifestyle changes.

Good Vibes

The practice of positive psychology focuses on growing human strengths to achieve greater levels of happiness, gratitude, and resilience.

Chazz Scott had it all. The successful career as a cybersecurity expert. The six-figure salary. The well-appointed condo overlooking the Potomac River and the high-end luxury car. From the outside, life looked good, but appearances can be deceiving, and they masked Scott’s inner turmoil. He was burned out at work and battled depression. He felt hollow and lacked passion for the things that once fueled his ambition and joy. While searching for ways to shake the malaise, Scott thought back to reading The Power of Positive Thinking by Norman Vincent Peale in college. The self-help book made him realize he could change his current reality simply by changing his mindset.

Scott knew he needed to focus on what was good in his life to create a positive energy that would build momentum toward fulfillment and contentment. It was a straightforward concept, but Scott’s science-based mind craved supporting evidence. He dove into researching neuroscience and discovered the fundamental elements of positive psychology, a relatively new field of study that helps people achieve higher levels of happiness and reach their true potential. Scott was fascinated by the field’s intersection with neuroscience, particularly as it relates to the study of neuroplasticity.

“For many years, it was widely assumed that people were stuck with their current way of thinking,” says Scott, who grew up in Ellicott City. “But we now know that the brain is capable of change through new thoughts and behaviors. With repetition

and consistency, new neuropathways are created and older, less-used pathways become weaker.”

About eight years ago, Scott began to incorporate positive psychology into his life by establishing a morning routine that prioritizes his physical and mental well-being. He wakes up at 5:30 a.m., goes for a brief jog, and completes stretching exercises before meditating for 20 minutes. He then carves out time for reading or listening to a podcast. This combination of movement, mindfulness, and mental growth sets a positive tone for his day and keeps him feeling balanced and productive. The seemingly minor steps resulted in gradual but profound changes to the way Scott viewed and lived his life.

“I feel happier, more resilient and better equipped to handle challenges that come my way,” he says. “Understanding that we all have the innate ability to change our mindset is incredibly empowering. It provides hope for something more.”

The nation’s mental health crisis and corporate burnout epidemic suggest millions of adults and adolescents need help in their

own search for more. That’s where positive psychology comes in. Its empirical study of the factors that allow some of us to thrive while others search endlessly for life’s true meaning helps to define true happiness and how to achieve it.

Positive psychology was popularized by Drs. Martin Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in the late 1990s as a departure from psychology’s traditional disease model, which focuses exclusively on treating mental disorders. Positive psychology does not address behavioral or emotional dysregulation and is not a substitute for treating severe mental illness. Instead, its interventions grow positive emotions and resources that help people maximize their true potential.

Dr. Seligman believes psychology should be just as concerned with human strength as it is with human weakness, and that it should focus on amplifying the best things in life while nurturing people’s innate talents.

“Positive psychology’s traits are skills that can be learned and strengthened, much like any other ability,” says Carly Hunt, who earned her PhD in counseling psychology

from the University of Maryland, where she was the faculty instructor of a course called Living the Good Life: The Psychology of Happiness. “With intentional practice, you can cultivate more gratitude in your life.”

Hunt played collegiate golf as an undergraduate at Georgetown University and as a graduate student at the University of Maryland. What she might have lacked in physical talent she more than made up for with mental toughness. “I’ve always been fascinated with sports psychology, positive self-talk, and the mental resilience athletes need to perform well,” she says.

At Georgetown, Hunt also took a Buddhist studies class. The coursework introduced her to mindfulness, self-compassion, loving kindness, and similar practices that led her to pursue a PhD at Maryland. Over the course of getting her PhD and doing a postdoctoral fellowship in biobehavioral pain research at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, she studied positive psychology’s impact on physical health and the mindbody connection.

Part of Hunt’s current work as the owner of Present Mind Consulting involves helping driven professionals and high-end talent build the confidence and motivation they need to achieve their goals. She works with performers, sports teams, and artists to address mental health challenges and cultivate personal strengths. She also collaborates with companies to develop strategies that enhance employee well-being and foster a healthier work environment.

Hunt works closely with Christopher Steer, who earned his law degree from the University of Maryland School of Law and now runs a consulting firm that helps companies achieve higher levels of organizational performance. Steer initially grasped the importance of positive leadership as an undergrad captain of the Johns Hopkins lacrosse team. That realization was reinforced by reading the book Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl, which introduced him to the idea of stimulus and response, and how the space between them is where growth, joy, happiness, and contentment happen.

“Personal evolution involves focusing on the things we can control rather than

At EviJoy Counseling Center, we understand that life’s challenges can feel overwhelming. Whether you’re an adolescent or an adult, our compassionate team of ten counselors can help you navigate stress, anxiety, depression, mood disorders, trauma and all facets of perinatal mental health. We specialize in providing support that empowers you to process and cope, so you can thrive through life’s toughest moments. Take the first step towards healing and resilience today.

“Positive psychology helps people build on their strengths or resilience resources like mindfulness, rewarding social connections, and compassion toward self and others.”

feeling like life is happening to us,” says Steer. “If you’re not getting the results you want, it’s time to explore a different path.”

Positivity—or good vibes, in the colloquial—is important, and people need to maximize their inner strengths, but Steer believes these feel-good ideas must link to tangible results. He says research reveals that executives and managers who lead with positivity drive better performance among their teams. That’s why high-level executives are increasingly interested in engaging in conversations about psychology, energy, and engagement. They’re realizing it’s not only acceptable but increasingly essential to embrace these concepts.

“Business leaders have started having conversations about emotional intelligence and the principles of positive psychology in the world of organizational development,” says Steer. “Modern neuroscience and psychology have finally converged within long-standing intuitions. Now, we can bring them together in a way that’s more accepted and impactful.”

Steer points to Satya Nadella, chairman and CEO of Microsoft. When Nadella took over the company, he instituted a peoplefocused approach and introduced Carol Dweck’s book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success as required reading. “Microsoft talking about mindset? That’s a gamechanger,” says Steer. “The right influencers, backed by solid research, can shift an organization’s culture.”

Positive psychology is no replacement for competitive salaries, good benefits, and the opportunity for professional growth, but Steer says research now reveals that corporate executives who lead with positivity

drive better performance, retention, and development. “You can’t commoditize dealing with people,” he adds, “but the ability to manage the human variable is becoming the most valuable skill.”

As we all know, life isn’t always easy. Hardships happen. Challenges are inevitable. In that sense, the term “positive psychology” is a bit of a misnomer. The practice is not concerned with papering over negative experiences. It’s more about finding tools to cope with negative experiences and even grow from painful events or adversity.

“Positive psychology helps people build on their strengths or resilience resources like mindfulness, rewarding social connections and compassion toward self and others,” says Hunt. “These resources help us withstand challenges and even thrive when facing them.”

Chazz Scott tuned his passion for positive psychology into the launch of Supra Mentem, a consulting business that specializes in helping executives, entrepreneurs, and professionals improve their overall well-being, reach peak performance, and achieve sustainable success. He emphasizes that embracing gratitude and experiencing positive emotions doesn’t involve ignoring life’s difficulties or being overly optimistic.

“Many of us don’t have effective coping strategies in place, so when stress occurs, we don’t know how to deal with it,” says Scott. “I’m now able to recognize when stress levels rise. I know to begin breathing exercises or meditation to get my body back to a state of balance. Having a set of practices to fall back on is essential for effectively managing life’s ups and downs.”

Scott has coached health care profes-

sionals, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, to reduce the negative impact of burnout. He’s also worked with successful professionals who are striving to achieve a better life balance. Many of them are midcareer, feeling disengaged and stressed, and realizing that their current work habits are unsustainable.

“They no longer feel fulfilled and may be contemplating a career change or questioning whether they are on the right path,” says Scott. “They seek guidance to restore balance and find a sense of purpose in their personal and professional lives.”

He knows from experience that positive psychology can help encourage professionals to reconnect with their true selves. “When you align with your personal wellness, even if the job isn’t the right fit, you can still improve your experience,” says Scott. “You can evaluate whether the job is something you still want or confirm that it’s time for a change. Focusing on your wellbeing allows you to make decisions with more clarity and greater confidence.”

Scott is also focused on addressing the youth mental health crisis through Positively Caviar, a grassroots nonprofit he launched to teach positive thinking and optimism to kids in underserved communities throughout Baltimore. Joan Wharton runs a mentorship program in conjunction with the Baltimore City Public Schools and partnered with Scott to lead a series of workshops for the girls at Cherry Hill Middle School.

“Chazz is very impressive and brought an energy that resonated with the girls,” says Wharton. “He met them where they were, and gradually helped raise them to another level. He taught them that the way they think shapes the way they act, and that what they feed their mind, soul, and spirit shows in their actions and attitudes.”

Scott’s workshops discussed personal growth and self-care. “His messaging focused on developing a positive mindset because the way the girls think can influence their behavior and the outcomes they experience,” says Wharton. “Having a positive mindset allows them to grow through empowerment and enlightenment and encourages them to build a strong foundation for

their future.” Weekly workshops aren’t going to solve the world’s problems, but Scott understands the importance of introducing tools to impressionable kids that help them cope with challenging situations. “My goal is to make sure they recognize that they have the agency to control what they think and feel,” he says. “It’s about giving them the ability to respond to their emotions in a healthy way.”

Interest in positive psychology is gaining traction among people who want to perform their best, regardless of their field or profession. But that doesn’t mean positivity can be pursued without consistent and intentional effort. Maximizing one’s potential demands daily focus and work.

“People rarely set aside the time and space in their lives to improve upon their strengths and virtues,” says Hunt. “Cultivating inner strengths and mental qualities that support happiness is something many of us long for and yet we often find ourselves racing toward the future, believing it holds some level of positivity that the present moment lacks.”

Even something as simple as jotting down three good things that happened throughout the day in a gratitude journal can be a powerful practice. Or you can practice “savoring,” which involves intentionally noticing and holding a positive experience in your awareness for 20 to 30 seconds, allowing yourself to fully absorb it. You might even visualize the positive feeling filling you.

The benefits of these practices have been studied extensively, according to Hunt, who says dedicating five to 10 minutes a day to them can be transformative over time.

Our brains naturally focus on the negative. Practices like gratitude, savoring, or acts of kindness help shift this bias, pulling us away from threat-focused thinking and into a mindset of greater positivity and altruism. Meditation and mindfulness, which encourage being fully present in the moment, reinforce these benefits. “What inspires me most is the universal application of positive psychology’s practices,” says Hunt. “We all strive for authentic happiness and fulfillment. At the end of the day, that’s at the core of what we want most in life.”

The Journey to Healing

The author, who survived street violence and prison with the help of therapy, makes the case for recognizing trauma in Baltimore and making counseling more accessible.

One day, I was sitting in my living room eating barbecue Pringles and working on my first book, a memoir of my life as a drug dealer, when a torrent of unexpected emotion rose up. I remember it like it was yesterday. I’d just started recounting the details of a shootout in broad daylight that I’d been involved in with a member of a rival crew decades earlier. As I wrote about the unnerving incident, it struck me, for the first time really, just how incredibly dangerous and reckless that situation had been. Years had passed since that day, but I had buried the memory until I started writing. Putting it on paper ripped open the scab on that old wound and revealed something I hadn’t thought much about.

Our brains have a way of pushing traumatic memories into the deep recesses of our minds, almost as if they never happened. But there I was with tears streaming down my face. Alone, struggling to maintain my composure, I was unsure why this old memory affected me so deeply. Then I realized I was distressed because I could have accidentally harmed an innocent child walking down the street that day—or I could have lost my own life.

After taking some time away from writing, I confided in a friend who worked in mental health services about what had happened. I also told her about my ongoing trouble sleeping and the nightmares. A short time later, I made an appointment with a therapist. That’s where the journey started for me, the journey toward healing.

For decades, I had ignored the traumatic incidents I experienced in the streets of Baltimore. Like when I was 16 years old, and a guy opened fire on me from just six feet away. I still don’t know how he missed but

TRAUMA BY KEVIN SHIRD

thank goodness he did. Or the time a teenage friend and I snuck into a nightclub to hear the tantalizing sounds of the early days of rap music, only to be traumatized when a man was shot and killed inside the club as we danced to the beat. Or the time I was hanging out in Druid Hill Park on a Sunday with some friends, and a man pulled out a handgun, placed it against another man’s head, and pulled the trigger.

Back then, as young men, we didn’t think much of incidents like these. In fact, we had normalized trauma, believing that we could just sleep it off and that it would be gone by morning. We never considered that witnessing these violent acts could affect our mental health decades later and that unresolved trauma could have a significant impact on our lives and decision-making ability. I never understood why I hated the sound of fireworks as a young man and would go out of my way to avoid New Year’s Eve and Fourth of July festivities that included fireworks.

Growing up in Baltimore, I experienced firsthand the challenges of systemic inequality, poverty, and the lure of the underground drug trade, as well as issues related to being the son of an alcoholic father.

These experiences led me into a life of crime, culminating in a federal prison sentence for drug trafficking. However, my incarceration marked a turning point, sparking a quest of self-reflection and redemption. While serving my sentence, I took college courses and began to reimagine my future, using education and personal growth as pathways to transformation.

Over the last 10 years I have authored several books that tackle complex social issues, often drawing from my own life to illuminate broader societal problems. A Life for a Life: Poor Choices and Unresolved Trauma Is Killing America (2025), which comes out this spring, is a true story that examines the intersection of trauma, mental health, and violence. It explores my relationship with

my former cellmate, Damion Neal, who tragically fell into violent crime after struggling with untreated mental health conditions. The book is both a personal reflection and a call to action to address systemic neglect of mental health and trauma. The Colored Waiting Room (2018), which was co-written with civil rights activist Nelson Malden, connects the legacy of the civil rights movement to

this role, I mentor students and continue my advocacy, hopefully inspiring the next generation of leaders and changemakers.

Healing is possible, and every Baltimore resident deserves a quality life.

contemporary struggles for racial and social justice. Uprising in the City (2016) focused on the death of Freddie Gray, the systemic inequalities faced by marginalized communities, and the steps necessary for meaningful rebuilding. My first book, the one that I was writing when the traumatic memory of the shoot-out leapt back into my conscious mind, was Lessons of Redemption (2014), which chronicled my transformation from a life of crime to becoming an advocate for justice and change.

My commitment to advocacy extends beyond writing. In 2014, I worked with the Obama Administration’s Clemency Initiative to address the inequities of the criminal justice system and advocate for fairer drug policies. I have also worked at the Johns Hopkins Center for Medical Humanities & Social Medicine to raise awareness around the public health crises in Baltimore and its effects on individuals and communities.

Currently, I serve as an instructor at Coppin State University, where I educate students about the links between social justice, criminal justice, and public health. Through

But the most significant area of my focus today is mental health. After being diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as a result of my early life and incarceration, I have become a vocal advocate for mental health awareness. My work highlights the impact of unresolved trauma and the need for compassionate approaches to mental health care. I know firsthand the impacts of trauma and stigma on one’s decision-making and how it has hindered communities of color from seeking treatment and counseling. I want to help tear down those barriers.

My personal story of drug dealing, gun violence, and incarceration may sound dramatic to many, but scores of people in Baltimore are trying to heal from growing up and living in a continuous state of survival. Entire neighborhoods have been subjected to generational poverty due to racist policies, leading to traumas stemming from systemic barriers to education, health care, safe housing, and economic insecurity. These obstacles include underfunded schools, limited access to mental health services, food deserts, inadequate transportation, unaffordable housing, and restricted job opportunities. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these vulnerabilities in communities already facing instability.

In the U.S., high rates of trauma and violence stem, in part, from a lack of coordination and commitment to mental health care. Locally, the homicide rate, though thankfully coming down, nonetheless remains at a very high level. The opioid epidemic in Baltimore City claims even more lives, nearly 6,000 over the past half a dozen years. Meanwhile, nearly one in four high school students across Baltimore seriously considered attempting suicide in the previous year, according to a recent Annie E. Casey Foundation study. And these are not issues that only impact Baltimore. Suicide is

the third leading cause of death for ages 1024 statewide in Maryland.

Inevitably, unresolved trauma becomes a major issue for youth affected by violence and opioid overdoses. Unlike physical wounds, psychological scars can persist indefinitely, often triggered by reminders of the past. These triggers vary widely, from loud noises and flashing lights to crowded spaces or even certain sights or smells. Addressing young people’s mental health needs requires a comprehensive approach that includes prevention and intervention, with therapy and counseling among the most effective tools to help them process experiences, develop coping skills, and gain control over their lives.

“When you live in fight-or-flight mode, it’s a daily reminder of the link between trauma and violence,” says Rev. Kim Lagree, CEO of Healing City Baltimore, a communitydriven organization that emphasizes trauma-informed practices and fosters compassion. One of Healing City Baltimore’s core beliefs is that addressing systemic racism is essential to treating today’s traumas. “A lot of homicides and opioid overdoses are rooted in people hurting and trying to cope. Our youth and communities face challenges with depression and anxiety, and often lack access to quality, culturally relevant services, [which are] typically designed by people who don’t look like those they serve.”

The good news is that Baltimore, with the Healing City initiative headed by Lagree, and Maryland, more broadly, have come to the forefront nationally as leaders in addressing long-ignored issues around trauma and its consequences.

In 2020, then-Mayor Jack Young signed the Elijah Cummings Healing City Act, an initiative pushed by now-City Council President Zeke Cohen, requiring that Baltimore City agencies eliminate policies that cause trauma to citizens and provide traumainformed training to all public-facing staff. In 2021, lawmakers in Annapolis passed the

Healing Maryland Trauma Act, sponsored by Baltimore State Senator Jill Carter and Delegate Robynn Lewis.

Lagree emphasizes that healing is possible, and that every Baltimore resident deserves a quality life. “An Ubuntu quote resonates with me: ‘I am because we are.’ It perfectly captures our belief that ‘if I am not free, then neither are you,’ and vice versa.”

One of Healing City Baltimore’s roles is serving as a hub for collaborators and mental health change agents. They assist organizations in developing solutions and strategies for communities that need access to quality, culturally relevant services.

“We elevate lived experiences as expertise and embrace the voices of youth and community leaders,” Lagree says. “Organizations like We Are Us, which connects directly with men in the streets, and Heart Smiles, a youth-led group training hundreds in trauma-informed care, are making a difference,” she adds.

Research shows that men, in particular, struggle to discuss mental health issues due to societal expectations and stigma. Men are often socialized to express emotions through actions rather than words—I’m no exception here—reinforcing norms of selfreliance and stoicism. Fear of judgment, limited role models who discuss mental health openly, and cultural stigma can make men reluctant to seek help. These factors often prevent them from addressing mental health needs until they become overwhelming.

During my time in prison, I had participated in a reentry program that addressed every issue imaginable, from criminal behavior to gambling and drug and alcohol addiction. The program leaders were strict: If you didn’t speak up and actively participate, you’d be kicked out, which could potentially impact your release date. After my release, I knew I needed to continue working on myself. So, when opportunities for therapy came up, I didn’t hesitate, though finding the right therapist proved to be a challenge.

As I talked with Lagree about the impact of unresolved trauma and recalled some of

my story, she shared what she went through growing up in Edmondson Village and how it informs her understanding today. Raised in a predominantly female-led family, Lagree witnessed the impacts of trauma firsthand. Her grandfather, a combat veteran, returned home with severe mental health issues and eventually became homeless. “He struggled with alcohol addiction and left home before I was born, when my mom was still in middle school,” Lagree says. “We couldn’t locate him for decades, leaving my grandmother to raise the family on her own. She was deeply religious and took me to church with her seven days a week. Despite our challenges, her resilience and faith provided a foundation for our family’s healing.”

Trauma affected multiple generations in Lagree’s family. “My mother and biological father both experienced addiction,” she continues. “My mom would disappear for days— or even months. Years later, when we had the chance to rebuild our relationship, the Black community still wasn’t openly discussing mental health. Growing up, it was expected that we handle family issues privately. For years, I experienced the emotional death of my mother countless times from age five to 20. Filing more than 30 missing persons reports alongside my grandmother had a significant mental impact.”

Along with speaking with Lagree about Healing City Baltimore and efforts to address trauma in the city, I also wanted to talk with Rev. Donte Hickman, whom I’ve actually known since our teenage years. One of the most respected faith and community leaders in the city, he offers a unique perspective on community healing from trauma, which includes having to rebuild a neighborhood senior housing complex that was under construction and destroyed in the Uprising after the death of Freddie Gray. Also, a Baltimore native, he has led the Southern Baptist Church on the east side of town for two decades. A pastor, he nonetheless believes that spirituality and religion should not be the sole tools for healing. He has long talked about the impact of trauma among city residents, youth

Hickman acknowledges that while Baltimore is making economic and infrastructure strides ... people and communities still grapple with trauma ... failure to adequately address these mental health needs will not just hold individuals back but hold the city back as well.

in particular, and the deep need for accessible mental health in Baltimore. “Spirituality should enhance social awareness, not blind us to reality,” he explains. “Some use it to block out real threats [to mental health].”

Hickman acknowledges that while Baltimore is making economic and infrastructure strides with redevelopment underway in many parts of the city, people and communities still grapple with trauma. Ex-offenders, for example, he says, face enormous challenges to healing when they return, and it can be difficult for them to navigate life outside of prison. Failure to adequately address these mental health needs will not just hold individuals back but hold the city back as well, he adds. “Healing can be misunderstood; spirituality is often misused, becoming a shield against pain,” Hickman says. “Karl Marx said, ‘religion is the opiate of the masses.’ Similarly, spirituality can insulate us from violence and trauma, giving a false sense of [physical and psychological] security.”

He believes true healing requires intentional effort. “We must first acknowledge what’s wrong, rather than using spirituality to avoid it. Instead, it should encourage us to confront our realities.”

The mental health impact of violence is profound in the neighborhoods around his church, especially among young people, leading to anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Children shouldn’t live in fear at school, worried about what’s around the corner, Hickman continues. “This contradicts the teachings of Jesus, who said, ‘I came that

they may have life, and have it abundantly.’”

In 2021, Hickman and his congregation faced the personal impact of random community violence when Evelyn Player, a church volunteer, was found dead in the church restroom. Hickman arrived to find police tape surrounding the church, shocked to learn she had been murdered. “I thought, ‘Who would stab a woman in a church?’ It made me realize that not everyone views the church as a sacred space,” he reflects.

After the tragedy, Hickman addressed the congregation about the complicated feeling of being protected by God in such a moment and organized a prayer vigil to honor Player and unite the community in the grieving and healing process. This collective spirit has been evident during past violence, such as the 2015 riots following Freddie Gray’s death. “We went door to door and engaged with seniors to understand their experiences,” he recalls.

The day of Player’s murder was no different. Hickman wanted to bring the community together to affirm their faith and support one another. Gov. Wes Moore, then a church member, attended the vigil, emphasizing the importance of community in the healing process.

Tragedies, such as the murder of a beloved community member like Evelyn Player or the death of an innocent man in police custody, as in the case of Freddie Gray, do have the potential to unite people across boundaries, fostering a shared determination to heal.

For long-overdue healing in Baltimore to occur, the community must show up

for each other, transcending both real and imagined divides, Hickman says. But there must still be broad and affordable access to mental health care as well. “If we ignore the needs of the least and most vulnerable in our communities,” Hickman says, “we will feel the repercussions in all neighborhoods.”

I also know firsthand the impact of trauma and stigma on one’s decision-making and how it has all too often hindered communities of color from seeking treatment and counseling. I want to help tear down those barriers and help communities return to being well again, but it’s also important that if I don’t take care of myself, I won’t be of much service to others.

A therapist once told me I had something called the “Superman Syndrome” or “Superman Complex.” It’s an unhealthy sense of responsibility rooted in the belief that others are incapable of handling even simple tasks on their own. Those with this complex—or its counterpart, Superwoman Syndrome—often see themselves as invincible and incapable of failure. They’re driven by an intense need to fix everyone around them, all while believing they have no issues of their own. She described me to a ‘T’ and that was the day that I started to pay more attention to my own emotions and my own feelings—and take on the problems of others as if they were my own.

At the same time, while writing my first book, Lessons of Redemption, I worried about how people might perceive my story. Gregory Kane, a former columnist for The Baltimore Sun, gave me invaluable advice: “Don’t worry about those fools. Just be honest in your writing.” Which is also good advice for life. I’ll never forget when he said, “Write until your hand falls off, and if it does, learn to write with the other hand.”

At the time, Kane was battling cancer, and his resilience inspired me. If he could fight that battle, I could certainly put words down on paper. Those moments, combined with my conviction to always rise to the occasion when it mattered, played a major role in shaping my journey.

Life

B y CHRISTIANNA MCCAUSLAND

line

WHAT’S BEHIND THE NEARLY 50,000 DEATHS BY SUICIDE IN THE UNITED STATES AND HOW CAN THEY BE PREVENTED?