The Choice

Bain Attwood on race, rights and history

*INC GST

Celebrating twenty years of great world poetry!

Entries are now open for the twentieth Peter Porter Poetry Prize, one of Australia’s most prestigious poetry awards. Worth a total of $10,000, the prize honours the great Australian poet Peter Porter (1929–2010).

This year’s judges are Dan Disney, Felicity Plunkett, and Lachlan Brown.

For more information, visit: australianbookreview.com/prizes-programs

First place $6,000

Four shortlisted poets $1,000 each

Entries close 9 October 2023

Category 2 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023

Advances

Prime Minister’s Literary Awards

In the December 2022 issue, some readers may recall, ABR lamented the tardiness of the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards and questioned the representativeness of two of the juries: fiction/poetry and non-fiction/Australian history. In our editorial, we also recalled past interference in the judging process by two former prime ministers (one Labor, one Liberal).

The industry was heartened, earlier this year, by the federal government’s announcement that responsibility for the management of the PMLAs (worth a total of $600,000 in prize money last year) would move from the Office for the Arts to the Australia Council for the Arts (soon to become Creative Australia), as part of Revive, the National Cultural Policy.

Since we are halfway through 2023, Advances has put several questions to the organisers, including: when the PMLAs will be opened; if the judges have been appointed; how representative the juries will be; when the shortlists will be announced; and when and where the official ceremony will take place.

As we went to press, we received this statement from the Australia Council: ‘We are working with the Office for the Arts through the transition, including the selection of the judges and timing of the announcements.’

Last year’s PMLAs were announced on 13 December, far too late in the publishing calendar, according to many publishers and booksellers. Let us hope that this year’s prizes – which should be so transformative for the winners and their commercial prospects – will be known well before then.

Backstage

To complement our four existing Q&As (Open Page, Poet of the Month, Critic of the Month, and Publisher of the Month), last month we created Backstage, a monthly column featuring a noted performing artist or someone closely associated with the arts sector. Fittingly, Robyn Archer – legendary performer and ABR’s second Laureate – inaugurated Backstage, with some typically pithy, original comments about seminal performances, favourite songs, artists she would have liked to work with, the best advice she’s ever received, and so forth.

Asked to nominate her favourite theatrical venue in Australia, Archer opted for the Dunstan Theatre at the Adelaide Festival Centre. Archer’s current national tour (An Australian Songbook), which supposedly coincides with

her seventy-fifth birthday (though we don’t believe it for a minute), took her to the Dunstan in mid-June. Chris Reid reviewed it for ABR Arts (now online).

This month’s Backstager is Helen Morse, veteran of theatre, film, and television – and a superb reader of poetry, too, as we were reminded during her tribute to Gwen Harwood at the recent Adelaide Writers’ festival.

Morse, who will soon perform in Caryl Churchill’s Escaped Alone for the MTC, has this advice for aspiring artists: ‘Train your voice, body, and mind, but don’t forget to live life! Serve the play – it’s all in the text.’ And her favourite venue? Fortyfivedownstairs, that valiant project in Flinders Lane, Melbourne.

Backstage appears on page 63. If Advances were on the ABC, we’d encourage you to nominate future Backstagers –but actually we’re always open to suggestions.

Reader survey

Apropos of openness, or suggestibility, we’re grateful to everyone who responded to our recent survey. Several hundred people did – thoughtfully, informedly, mostly supportively, sometimes grumpily (what’s a survey without a bit of ‘lively feedback’!).

We’ll repeat the survey in due course, all part of our ongoing refreshment of the magazine that obviously means as much to many readers as it does to everyone at ABR.

We offered two prizes in our promotion. Judith Bishop has won a bundle of tickets to the Spanish Film Festival, courtesy of Palace Films, and Prakash Subedi receives a three-year digital subscription.

Facsimile edition

One response did surprise Advances. Asked to nominate their preferred format of ABR, almost ten per cent of respondents named the facsimile edition (the digital reproduction of the print edition that we produce each month). We had no idea so many people were using it regularly. ABR started to publish this format in 2020 because of the long postal delays caused by Covid-19. Now, it seems, many readers are turning to this add-on digital version, which offers a facsimile of the entire issue – ads and all!

A reminder to all our subscribers (print or digital): you can access the facsimile edition via our website.

Encouraged by the response, we will now set about

[Advances continues on page 9]

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023 3

The old songs are always new Singing traditions of the Tiwi Islands

AVAILABLE NOW

Genevieve Campbell with Tiwi Elders and knowledge holders

Australian Book Review

July 2023, no. 455

First series 1961–74 | Second series (1978 onwards, from no. 1)

Registered by Australia Post | Printed by Doran Printing

ISSN 0155-2864

ABR is published eleven times a year by Australian Book Review Inc., which is an association incorporated in Victoria, registered no. A0037102Z.

Phone: (03) 9699 8822

Twitter: @AustBookReview

Facebook: @AustralianBookReview

Instagram: @AustralianBookReview

Postal address: Studio 2, 207 City Road, Southbank, Vic. 3006 This is a Creative Spaces studio. Creative Spaces is a program of Arts Melbourne at the City of Melbourne. www.australianbookreview.com.au

Peter Rose | Editor and CEO editor@australianbookreview.com.au

Amy Baillieu | Deputy Editor abr@australianbookreview.com.au

Georgina Arnott | Assistant Editor assistant@australianbookreview.com.au

Grace Chang | Business Manager business@australianbookreview.com.au

Christopher Menz | Development Consultant development@australianbookreview.com.au

Poetry Editor

John Hawke (with assistance from Anders Villani)

Chair Sarah Holland-Batt

Deputy Chair Billy Griffiths

Treasurer Peter McLennan

Board Members Graham Anderson, Declan Fry, Johanna Leggatt, Lynette Russell, Robert Sessions, Beejay Silcox, Katie Stevenson, Geordie Williamson

ABR Laureates

David Malouf (2014) | Robyn Archer (2016) Sheila Fitzpatrick (2023)

ABR Rising Stars

Alex Tighe (2019) | Sarah Walker (2019) | Declan Fry (2020) Anders Villani (2021) | Mindy Gill (2021)

Monash University Interns

Will Hunt, Menachem New, Kai Norris

Volunteers

Alan Haig, John Scully

Contributors

The ❖ symbol next to a contributor’s name denotes that it is their first appearance in the magazine.

Acknowledgment of Country

Australian Book Review acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the Kulin Nation as Traditional Owners of the land on which it is situated in Southbank, Victoria, and pays respect to the Elders, past and present. ABR writers similarly acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands on which they live.

Subscriptions

One year (print + online): $100 | One year (online only): $80

Subscription rates above are for individuals in Australia. All prices include GST. More information about subscription rates, including international, concession, and institutional rates is available: www.australianbookreview.com.au

Email: business@australianbookreview.com.au

Phone: (03) 9699 8822

Cover Design

Amy Baillieu

Letters to the Editor

We welcome succinct letters and online comments. Letters and online comments are subject to editing. The letters and online comments published by Australian Book Review are the opinions of the named contributor and not those of ABR. Correspondents must provide contact details: letters@australianbookreview.com.au

Advertising

Amy Baillieu – abr@australianbookreview.com.au Media Kit available from our website.

Environment

Australian Book Review is printed by Doran Printing, an FSC® certified printer (C005519). Doran Printing uses clean energy provided by Hydro Tasmania. All inks are soy-based, and all paper waste is recycled to make new paper products.

Image credits and information

Front cover: Photograph by Brent Lukey, www.brentlukey.com

Page 31: J.M. Coetzee (MALBA Buenos Aires, 2014, viaText Publishing)

Page 57: Helen Morse in Rivers of China, a 1988 Melbourne Theatre Company production – photograph by Jeff Busby

4 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023

ABR July 2023

LETTERS

COMMENTARY MEDIA

HISTORY

John Carmody, Dennis Muirhead, Lyn Jacobs

Bain Attwood

David Rolph

Jack Corbett

Ebony Nilsson

Patrick Mullins

Sheila Fitzpatrick

Georgina Arnott

Ceridwen Spark

A referendum in trouble

A vindication of investigative journalism

Sovereignty games in the Pacific Islands

The ALP’s uneasy history with immigration

Media Monsters by Sally Young

Beyond the Wall by Katja Hoyer

The Lives and Legacies of a Carceral Island by Ann Curthoys, Shino Konishi, and Alexandra Ludewig

Helpem Fren by Michael Wesley

BIOGRAPHY

MEMOIR

INDIGENOUS STUDIES

POEMS

ECONOMICS

FICTION

Michael Hofmann

Brenda Walker

Kevin Foster

Malcolm Allbrook

Anthony Lawrence

Lisa Samuels

Knox Peden

Geordie Williamson

Andrew van der Vlies

Naama Grey-Smith

Giselle Au-Nhien Nguyen

Jay Daniel Thompson

Scott McCulloch

Wifedom by Anna Funder

Eleven Letters to You by Helen Elliott

Line in the Sand by Dean Yates

The Queen Is Dead by Stan Grant

‘Reading the Conditions’ ‘Dise’

Capitalism by Michael Sonenscher

The Pole and Other Stories by J.M. Coetzee

The Five Sorrowful Mysteries of Andy Africa by Stephen Buoro

The Fire and the Rose by Robyn Cadwallader

After the Rain by Aisling Smith

Where I Slept by Libby Angel

Anam by André Dao

LITERARY STUDIES

POETRY

Philip Mead

Felicity Plunkett

Chris Arnold

Barron Field in New South Wales by Thomas H. Ford and Justin Clemens

Spore or Seed by Caitlin Maling and Increments of the Everyday by Rose Lucas

I Have Decided to Remain Vertical by Gaylene Carbis and The Drama Student by Autumn Royal

NATURAL HISTORY

ENVIRONMENT

LESBIAN STUDIES

INTERVIEWS

ABR ARTS FROM THE ARCHIVE

Danielle Clode

Ruby Ekkel

Susan Sheridan

Nick McKenzie

Helen Morse

Josh Stenberg

Kirk Dodd

Anwen Crawford

Clare Monagle

Jo Case

Goldfish in the Parlour by John Simons

The Power of Trees by Peter Wohlleben, translated by Jane Billinghurst

She and Her Pretty Friend by Danielle Scrimshaw

Open Page Backstage

The Poison of Polygamy

A Streetcar Named Desire

Saint Omer

Do Not Go Gentle

All That I Am by Anna Funder

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023 5

8 10 17 23 29 15 19 33 46 20 22 45 26 27 43 32 36 38 39 40 41 42 44 48 50 51 54 55 56 63 58 59 60 62 64

Our partners

Australian Book Review is assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council for the Arts, its arts funding and advisory body. ABR is supported by the South Australian Government through Arts South Australia.

We also acknowledge the generous support of our university partner Monash University; and we are grateful for the support of the Copyright Agency Cultural Fund; Good Business Foundation (an initiative of Peter McMullin AM), Australian Communities Foundation, the City of Melbourne; and Arnold Bloch Leibler.

Arts South Australia

6 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023

ABR Patrons

The Australian Government has approved ABR as a Deductible Gift Recipient (DGR).

All donations of $2 or more are tax deductible. To discuss becoming an ABR Patron or donating to ABR, contact us by email: development@australianbookreview.com.au or by phone: (03) 9699 8822.

In recognition of our Patrons’ continuing generosity, ABR records multiple donations cumulatively. (ABR Patrons listing as at 22 June 2023)

Parnassian ($100,000 or more)

Ian Dickson AM

Acmeist ($75,000 to $99,999)

Blake Beckett Fund

Morag Fraser AM

Maria Myers AC

Olympian ($50,000 to $74,999)

Anita Apsitis and Graham Anderson

Colin Golvan AM KC

Augustan ($25,000 to $49,999)

In memory of Kate Boyce, 1935–2020

Dr Steve and Mrs TJ Christie

Professor Glyn Davis AC and Professor Margaret Gardner AC

Pauline Menz (d. 2022)

Lady Potter AC CMRI

Ruth and Ralph Renard

Mary-Ruth Sindrey and Peter McLennan

Kim Williams AM

Anonymous (2)

Imagist ($15,000 to $24,999)

Australian Communities Foundation (Koshland Innovation Fund)

Emeritus Professor David Carment AM

Emeritus Professor Margaret Plant

Peter Rose and Christopher Menz

John Scully

Emeritus Professor Andrew Taylor AM

Vorticist ($10,000 to $14,999)

Peter Allan

Geoffrey Applegate OBE (d. 2021) and Sue Glenton

Dr Neal Blewett AC

Helen Brack

Emeritus Professor Anne Edwards AO

Good Business Foundation (an initiative of Peter McMullin AM)

Dr Alastair Jackson AM

Neil Kaplan CBE KC and Su Lesser

Steve Morton

Allan Murray-Jones

Susan Nathan

Professor Colin Nettelbeck (d. 2022) and Ms Carol Nettelbeck

David Poulton

Emeritus Professor Ilana Snyder and Dr Ray Snyder AM

Susan Varga

Futurist ($5,000 to $9,999)

Gillian Appleton

Professor The Hon. Kevin Bell AM KC and Tricia Byrnes

Professor Frank Bongiorno AM

Dr Bernadette Brennan

Des Cowley

Professor The Hon. Gareth Evans AC KC

Helen Garner

Cathrine Harboe-Ree AM

Professor Margaret Harris

Linsay and John Knight

Dr Susan Lever OAM

Don Meadows

Jillian Pappas

Judith Pini

(honouring Agnes Helen Pini, 1939–2016)

Professor John Rickard

Robert Sessions AM

Noel Turnbull

Mary Vallentine AO

Bret Walker AO SC

Nicola Wass

Lyn Williams AM

Ruth Wisniak OAM and Dr John Miller AO

Anonymous (3)

Modernist ($2,500 to $4,999)

Professor Dennis Altman AM

Helen Angus

Australian Communities Foundation (JRA Support Fund)

Kate Baillieu

Judith Bishop and Petr Kuzmin

Professor Jan Carter AM

Donna Curran and Patrick McCaughey

Emeritus Professor Helen Ennis

Roslyn Follett

Professor Paul Giles

Jock Given

Dr Joan Grant

Dr Gavan Griffith AO KC

Tom Griffiths

Dr Michael Henry AM

Mary Hoban

Claudia Hyles OAM

Dr Barbara Kamler

Professor Marilyn Lake AO

Professor John Langmore AM

Kimberly Kushman McCarthy and Julian McCarthy

Pamela McLure

Dr Stephen McNamara

Rod Morrison

Stephen Newton AO

Angela Nordlinger

Emeritus Professor Roger Rees

Dr Trish Richardson (in memory of Andy Lloyd James 1944–2022)

Emerita Professor Susan Sheridan and Emerita Professor Susan Magarey AM

Dr Jennifer Strauss AM

Professor Janna Thompson (d. 2022)

Lisa Turner

Dr Barbara Wall

Emeritus Professor James Walter

Emeritus Professor Elizabeth Webby AM

Anonymous (2)

Romantic ($1,000 to $2,499)

Damian and Sandra Abrahams

Lyle Allan

Paul Anderson

Australian Communities Foundation

Gary and Judith Berson

Jim Davidson AM

Joel Deane

Jason Drewe

Allan Driver

Jean Dunn

Elly Fink

Professor Sheila Fitzpatrick

Stuart Flavell

Steve Gome

Anne Grindrod

Associate Professor Michael Halliwell

Professor Sarah Holland-Batt

Anthony Kane

Professor Mark Kenny

Alison Leslie

David Loggia

Dr Brian McFarlane OAM

Emeritus Professor Peter McPhee AM

Felicity St John Moore

Penelope Nelson

Dr Brenda Niall AO

Jane Novak

Professor Michael L. Ondaatje

Diana and Helen O’Neil

Barbara Paterson

Estate of Dorothy Porter

Mark Powell

Emeritus Professor Wilfrid Prest AM

Ann Marie Ritchie

Libby Robin

Stephen Robinson

Professor David Rolph

Dr Della Rowley (in memory of Hazel Rowley, 1951–2011)

Professor Lynette Russell AM

Dr Francesca Jurate Sasnaitis

8 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023

Michael Shmith

Dr Diana M. Thomas

Professor David Throsby AO and Dr Robin Hughes AO

Dr Helen Tyzack

Ursula Whiteside

Kyle Wilson

Dr Diana and Mr John Wyndham

Anonymous (5)

Symbolist ($500 to $999)

Douglas Batten

Jean Bloomfield

Raymond Bonner

Professor Kate Burridge

Dr Jill Burton

Brian Chatterton OAM

Professor Graeme Davison AO

Dilan Gunawardana

Robyn Hewitt

Dr Amanda Johnson

Michael Macgeorge

Hon. Chris Maxwell AC

Emeritus Professor Michael Morley

Patricia Nethery

Mark O’Donoghue

Gillian Pauli

Anastasios Piperoglou

Professor Carroll Pursell and Professor Angela Woollacott

Dr Ron Radford AM

Alex Skovron

Professor Christina Twomey

Anonymous (1)

Realist ($250 to $499)

Dr Linda Atkins

Caroline Bailey

Jennifer Bryce

Antonio Di Dio

Barbara Hoad

Margaret Hollingdale

Margaret Robson Kett

Ian McKenzie

Margaret Smith

Emeritus Professor Graham Tulloch

Dr Gary Werskey

Anonymous (1)

Bequests and notified bequests

Gillian Appleton

Ian Dickson AM

John Button (1933–2008)

Peter Corrigan AM (1941–2016)

Dr Kerryn Goldsworthy

Kimberly Kushman McCarthy and Julian McCarthy

Peter Rose

Dr Francesca Jurate Sasnaitis

Denise Smith

Anonymous (3)

The ABR Podcast

Our weekly podcast includes interviews with ABR writers, major reviews, and creative writing. Here are some recent and coming episodes.

Race, rights and history

Bain Attwood

Ben Roberts-Smith

David Rolph

Slut Trouble

Beejay Silcox

Politics in India

John Zubrzycki

Calibre Essay Prize

Tracy Ellis

Westminster politics

Gordon Pentland

Child Adjacent

Bridget Vincent

Elizabeth Hardwick

Peter Rose

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023 9

What do Monash University, the Zentralbibliothek Zurich and the University of Pennsylvania have in common?

They all subscribe to Australian Book Review

ABR publishes Australia’s most distinguished academics, its finest long-form journalism, and reviews scholarly publications from around the world.

ABR is a rich and essential digital resource for academics and students. Why not trial a digital subscription now for your institution?

Eleven new issues each year

A rapidly growing digital archive of content from 1978

Long-form academic articles, reviews, and commentary

Access via IP address authentication for institutions

Usage statistics on request

Request your free one-month digital subscription to ABR today

australianbookreview.com.au/subscribe

Matheson Library atrium, Monash University, Clayton (photograph by Dianna Snape)

Matheson Library atrium, Monash University, Clayton (photograph by Dianna Snape)

*INC GST The Choice Bain Attwood on race, rights and history

creating facsimiles of all past issues of ABR, to complement our unique digital archive going back to 1978.

Peter Porter Poetry Prize

Where have the years gone? It’s been thirteen years since Peter Porter, one Australia’s greatest poets, died, and nineteen since ABR first offered the poetry prize that now – abundantly alliteratively – bears his name. Open to all poets writing in English around the world since 2014, the Porter Prize has become one of the world’s leading awards for a new poem. Past winners include Judith Bishop and Anthony Lawrence (twice each), Judith Beveridge, Stephen Edgar, and Sara M. Saleh.

The twentieth Porter Prize will open on 3 July, with a closing date of 9 October. Again, we welcome poems of all shapes and styles. The prize money totals $10,000, with a first prize of $6,000, to be chosen by our three judges, distinguished poets all: Lachlan Brown (shortlisted in 2020), Dan Disney

Fickle testimony

Dear Editor,

(winner in 2023), and Maria Takolander (shortlisted in 2005). Full details appear on our website.

We remain truly grateful to the prize’s principal patron, Morag Fraser, and also to Andrew Taylor.

Brent Lukey

Amy Baillieu – Deputy Editor of ABR – has done some fine covers this year, but this month’s one is choice, greatly helped by a characteristically stylish and atmospheric photograph from Melbourne artist Brent Lukey, a finalist in the 2023 Olive Cotton Award. Brent is actually a neighbour of ours at the Boyd Community Hub, through Creative Spaces, our mutual landlord. It’s great to have him on our cover.

The finalists’ works in the Olive Cotton Award will be on display at the Tweed Regional Gallery (NSW) from 14 July to 24 September. Brent’s entry is a luminous new portrait of Marcia Langton. g

Letters

I was surprised that neither Kate Lilley, in her warm tribute to the late John Tranter (ABR, June 2023), like Philip Mead in his detailed Sydney Morning Herald obituary (8 May), mentioned the ‘poetry wars’ between Tranter and Les Murray in the 1970s, which were so bitter that, at the last moment, Murray even withdrew from an Academics and Writers conference (at the University of New South Wales) because Tranter was scheduled to speak on the following day.

When I wrote to them a few years ago asking about the true basis of that ‘war’, both poets flatly denied all recollection of any such thing. Testimony, plainly, is fickle and fallible.

John Carmody

Barry Humphries in full flight

Dear Editor,

I am grateful to Peter Tregear for his tribute to Barry Humphries (ABR, June 2023).

I first saw Humphries in Adelaide in 1960, when Edna Everage was a much gentler character. My favourite was and remains Sandy Stone, who was so laid-back in his chair and slippers that I didn’t think he would get up again.

The last time I saw Humphries was at Australia House in 2019 at a University Alumni event. It was rumoured that Humphries would attend, but there was no sign of him until the vice-chancellor was halfway through his speech. The double doors of the room were suddenly flung open and there was Humphries, in hat, coat, and scarf. He pushed his way through the standing crowd and positioned himself halfway between the audience and the vice-chancellor. Unannounced, he interrupted the vice-chancellor and broke into a speech as Barry Humphries that had us all in stitches for thirty minutes. As he spoke, he patrolled the front row of people, who feared they might be picked on by Edna. Humphries exhausted

himself and stopped. He had a quick word with the vicechancellor, spoke calmly to a few members of the audience, and left through the same double doors that hadn’t closed.

I will miss him.

Beyond the lane

Dear Editor,

Dennis Muirhead (online comment)

Oxford is a favoured setting for novels exploring tensions between town and gown (from Jill Paton Walsh’s renovations of Dorothy Sayers’s texts to R.F. Kuang’s more recent dismantling of power in Babel), but Pip Williams’s depiction of The Bookbinder of Jericho (reviewed by Jane Sullivan in the May issue) embraces issues of language and loyalty that troubled an ancient walled city, and not simply a district in a university town, in a country fractured by class, education, repressed aspiration, and diminished opportunity.

At its heart is a love story that celebrates a gift of creation in one man’s restoration of women’s words arbitrarily censored. The bookbinder who sorts, repairs, and steals fragments of revered texts in order to read the byways of a world beyond the ‘lane’ that is Oxford, is an agent registering change at a place and time of world crisis, where words have irremediably tipped order into chaos. Beyond the grand rhetoric, where the limbs of compatriots and enemy are being amputated or the horrors of witness transcend speech, mute silence shouts. Williams’s text is metaphoric, an evocatively nuanced investigation of the power, eloquence, saving grace, and inadequacy of the languages of the world’s words. But Williams implies that the narrow boat, with its remnant but resilient human cargo fighting to stay afloat, offers a potential for recovery in the face of change.

For its kindness and acuity, this generous book will undoubtedly be rightly treasured.

Lyn Jacobs

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023 11

A referendum in trouble

Race, rights, and history talk in 1967 and 2023

by Bain Attwood

On 27 May 1967, a proposal to change two clauses of the Australian Constitution won the approval of 90.77 per cent of those who voted, the highest ever achieved in an Australian referendum. In the forthcoming referendum, according to various opinion polls, the best the advocates for a ‘yes’ vote can hope to achieve is a bare majority. How can this difference be explained? Several factors appear to be at work. They range from the simple, which are acknowledged, to the complex, which don’t seem to be known.

In 1967 the Aboriginal question in the referendum enjoyed bipartisan support or at least no major political party recommended the punters vote ‘no’. No official ‘no’ case was presented. Few Australians expressed misgivings about the ‘yes’ case in the media. No one campaigned against it. The forthcoming referendum does not have bipartisan support. There will be an official ‘no’ case. And many non-Indigenous and some Indigenous people have already expressed opposition to the proposal.

No political party took the lead in the 1967 referendum campaign. It was dominated instead by FCAATSI (the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders) – an organisation that had been campaigning for a referendum since 1958 – and its allies in the trade unions and the churches.

In 1967, it was the Liberal-Country Party Coalition government of the day that was responsible for sponsoring the legislation that enabled the referendum to occur. But it was only lukewarm about the proposal to change two clauses of the Constitution in regard to Aboriginal people, and so played hardly any role in the campaign. This time the Labor Party is sponsoring the referendum and is driving the campaign – and, more importantly, it is seen by most voters to be doing so.

There was a second question in the 1967 referendum – known as ‘the nexus question’ – to increase the number of members in the House of Representatives relative to the number of members in the Senate. This was strongly supported by both the Liberal and Labor parties, but received only 40.25 per cent support. Perhaps

the presence of this question on the polling paper gave voters an opportunity to express a residual suspicion of the political class and yet still vote ‘yes’ to the Aboriginal question. The forthcoming referendum provides nothing of the kind.

The factors I have just discussed provide some explanation of why we cannot even conceive of a huge ‘yes’ vote in the forthcoming referendum. But I doubt they are the most important. I suggest the reasons lie elsewhere, in the enormous changes that have occurred in Australia since 1967 in regard to a series of intersecting discourses (or talk) about what we might call race, rights, history, and culture.

Campaigners for a ‘yes’ vote in 1967 led an assault on ways of thinking and acting that were rooted in notions of racial difference. They believed that the disadvantages that contemporary Aboriginal people suffered were a result of the fact that they had long been treated as different. The white campaigners held that Aboriginal people would be better off if all Australians could largely transcend a sense of being racially (or culturally) different. Aboriginal people were to be assimilated into a common Australian culture. While they might remain different, their cultural difference was not considered to be terribly significant.

The rights the campaigners sought in 1967 were those of citizenship (even though Aboriginal people had been granted those rights, which included the right to vote, in the ten years that preceded the referendum, largely as a result of the repeal of racially discriminatory legislation). That is, the campaigners demanded for Aboriginal people the same rights as other Australians enjoyed – what they called ‘equal rights’.

To be sure, some of the campaigners had another kind of rights in mind – what we can call special rights – which was why FCAATSI had sought the amendment of section 51 (26) of the Constitution, which gave the Commonwealth the power to pass special laws for ‘the people of any race, other than the aboriginal people in any state, for whom it is necessary to make special laws’ – rather than its repeal.

The special rights the campaigners called for were concep-

12 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023

Commentary

tualised by them in two particular ways. First, as temporary in nature: Aboriginal people would enjoy what amounted to a form of positive discrimination to enable them to overcome the disadvantages they presently suffered, but at some point in the not-so-distant future it was assumed that those rights would no longer be necessary and so would cease to be granted. Second, as individual rights, not as group rights: rights that Aboriginal people could claim on the basis of being members of Australian society, not rights that they could claim by virtue of the fact that they belonged to a group, the Aboriginal race.

This kind of rights talk barely featured in the campaign as the campaigners realised that they might trouble many voters. They urged them to ‘Vote Yes for Aboriginal Rights’, but the ‘Aboriginal rights’ they spoke most about were those associated with Australian citizenship and thus the same ones that all Australians enjoyed.

History – by which I mean the stories we tell about the past – played some role in the 1967 referendum. Campaigners told voters that Aboriginal people had been treated poorly in the past and that this had to be redressed. But they merely drew attention to that past as a means to realise their goal of equality for Aboriginal people in the future.

If history played only a small part in the referendum, this was even truer of culture in the sense that is spoken about now. The major political parties conceived of cultural difference among Australians in very different terms, not the least of which was class, and sometimes religion.

The ways in which the campaigners presented the 1967 referendum to the predominantly white Australian voters in terms of race, rights, and history made it relatively easy for the vast majority of them to embrace the modest constitutional changes that were being proposed. (In addition to the one I have already mentioned, section 127 was to be repealed so that Aboriginal people could be counted in the national census, rather than by some other governmental procedure.) They appealed, we could say, to their best selves, as Gordon Bryant, a vice-president of FCAATSI and a Labor member of the Commonwealth parliament, remarked shortly after the resounding ‘yes’ vote:

The average voter at the time of the referendum … may not have known very much about the Aboriginal question and probably had the idea, based on a good Australian tradition, that the Aboriginal people of this country had not had a fair go. Most voters probably had vague ideas that the Aboriginals [did not have] full citizenship rights and might not be able to vote. Doubtless some voters were misinformed on many matters, but most were directed by their consciences and sense of social justice to take the view that something ought to have been done to better the lot of the Aboriginal people (my emphasis).

To put this another way, the campaigners presented their case in such a way that white Australians could feel that by voting ‘yes’ they were bestowing on Aboriginal people the same rights and privileges they had and were thereby enabling them to become Australians just like them. In voting ‘yes’, they were able to feel proud rather than ashamed that the changes were badly needed (though the campaigners undoubtedly raised the spectre of

Australia’s reputation being tarnished if the people voted ‘no’).

The talk about race, rights, and history in 2023 is very different from what it was in 1967. Indeed, this has been the case for several decades, and by and large for the better in my opinion.

The vision of those who are advocating voting ‘yes’, and especially the vision of Aboriginal people (who played only a minor role in the 1967 campaign, for reasons we can attribute to the history of race in this country), is racial in nature rather than non-racial. Unlike in 1967, racial difference – or what some might prefer to call cultural difference – is regarded as something to be embraced, nurtured, celebrated. To be different, and to be regarded as different, is, in large part, no longer seen by most people as something bad but as something good. (This had always

been the case for white or at least British Australians: once upon a time they talked a great deal about being racially different and they celebrated it.)

The rights for Aboriginal people that have been most sought for a long time now are not those of citizenship – that is, the rights all Australian citizens can claim irrespective of their differences – but Indigenous rights, that is, the rights that only Indigenous people can claim on the basis of the fact that they trace at least some of their ancestry to the original or Aboriginal peoples of this land.

These rights are also special ones, but they are very different

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023 13

Harold Holt and two government MPs meeting with representatives of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI).

L-R: Gordon Bryant, Faith Bandler, Harold Holt, Doug Nicholls, Burnum Burnum, Winnie Branson, and Bill Wentworth, February 1967 (National Archives of Australia via Wikimedia Commons)

from the special rights I mentioned earlier. They are conceptualised as being permanent rather than temporary in nature, and they are claimed on the ground that Aboriginal people are members of a group rather than individuals. Liberal democracies have long found it more difficult to accommodate claims to this kind of special rights claims – that is, collective rights – than the individual rights mentioned earlier: for example, Australian governments have long granted individual returned servicemen –or at least those servicemen classified as non-Aboriginal – what amount to special rights.

The past is more fundamental to the forthcoming referendum than it was in 1967. Indigenous rights are essentially historical in nature, as they rest on a historical fact that Aboriginal people are the first peoples of this land. Claiming them demands a good deal of talk about Australia’s black history.

In short, contemporary talk about race, rights, and history means that the future of Aboriginal people in relationship to the non-Aboriginal majority is figured very differently from the way it was in 1967. This lies at the very heart of what is being proposed in the forthcoming referendum. First, that Aboriginal people be recognised as different from other Australians on the basis that they are the country’s first peoples. Second, that a ‘voice’ to both the legislative and executive wings of government be formally created for Aboriginal people that no other racial or ethnic group in Australia enjoys (but which practically all such groups already have in an informal sense).

The nature of present-day thinking about rights, race, and history, unlike that in 1967, evidently troubles many nonIndigenous voters as it places them on what is deemed by many other Australians to be the wrong side of history. This threatens to rob them of the powerful feeling many white Australians long enjoyed, that of imagining themselves as victims and being recognised as such by others. The proposal in the referendum, despite the fact that it is very modest, can be interpreted by such voters as one that discriminates against them as Aboriginal people stand to gain something they don’t and can’t have – because they are not Aboriginal. Furthermore, the basis of what is being sought by Aboriginal people rests on a history that is characterised as inherently shameful, involving as it does the legacies of the dispossession, displacement, decimation, deprivation, and discrimination that the nation’s first peoples have suffered.

In short, the profound shifts that have taken place in thinking about race, rights, and history in Australia in the decades since 1967 mean that campaigning for a ‘yes’ vote is an infinitely more difficult task than it was fifty-six years ago.

Yet this would not be so much the case had not several other profound changes taken place in Australia in recent decades.

The first concerns the politics of recognition, whether this

involves claims for legal, cultural, or historical recognition, or all three of them, as is the case in the forthcoming referendum. The politics of recognition is a form of politics in which those people who can be said to belong to the majority in any society are called upon to help alleviate the pain and suffering of minorities by recognising their loss and suffering. When this kind of politics emerged more than thirty years ago, it was part of another kind of politics – the politics of distribution – which can be defined as a politics of socio-economic distribution that seeks to bring about a fairer and more equal society by shifting a portion of the goods of the rich to the poor. In recent years, the connection between these two kinds of politics, once taken for granted, has diminished, perhaps even to the point that it has been severed. It often seems that many of those who champion the Aboriginal cause have convinced themselves that the politics of recognition on its own amounts to a serious form of ameliorative politics.

The fracturing of the connection between the politics of recognition and the politics of redistribution means two things. Many if not most of those people advocating a ‘yes’ vote are now finding it very difficult to explain to others, if not themselves, how voting ‘yes’ in a referendum that is largely presented as being about recognition will bring about the radical changes that are required if the ongoing disadvantage that most Aboriginal people continue to suffer is to be addressed.

Even the leading Aboriginal advocates of the ‘yes’ case struggle to explain the connection between the ‘recognition’ part of the referendum and the ‘voice’ part of it. This is not to say that there is no connection, merely that the connection is by no means self-evident.

Presumably, the connection between these two parts of the referendum lies in a belief that politics must become three-dimensional so that it incorporates not only the socio-economic dimension of distribution and the cultural, historical, and legal one of recognition, but also one that can be called representation: that recognition and distribution are necessary but insufficient to bring about the amelioration that most Aboriginal people require. In other words, it must be explained to voters that recognition of, plus representation for, Aboriginal people are required in order to achieve the much-needed redistribution.

Ninety years ago, an Aboriginal advocate, William Cooper, used a term that explained to White Australia why he was calling for an Aboriginal voice in parliament: ‘thinking black’. He told Australia’s political leaders that no matter how sympathetic whitefellas were to the plight of his people, they could not ‘think black’. He called upon them to recognise that fact and act accordingly, creating a mechanism by which blackfellas could provide their perspective: an Aboriginal voice to government.

14 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023

A promotional badge concerning the 1967 Australian constitutional referendum, in the collections of Museums Victoria (photograph by Jon Augier for Museums Victoria via Wikimedia Commons)

These days few seem to have the political acumen required to explain why an Aboriginal voice to government is important. Perhaps this is because the political language of redistribution has fallen into disuse. Once upon a time the Labor Party used it as a matter of course in talking about Aboriginal affairs. They have tried using it again recently but have done this so self-consciously that it hasn’t persuaded those sceptical about the need for the Voice.

The campaigners not only need to explain the connection between the two parts of the referendum. They must also do what the 1967 referendum campaigners did: tell a really good story so they can appeal to voters’ minds, but more especially their hearts. This is the case, political psychologists tell us, because the political brain is an emotional brain. So far, the proponents of the ‘no’ vote have done a much better job in this respect.

If the 1967 referendum is anything to go by, the story that needs to be told to achieve a majority for the ‘yes’ case will be a big, symbolic one that doesn’t necessarily have any obvious connection to the modest reform being proposed. In 1967, the campaigners spun a moving story about counting Aboriginal people as Australians and making them citizens – giving them a fair go, as Gordon Bryant put it.

Another major change that is making it difficult for the ‘yes’ case to gain sufficient traction is the fact that for thirty or more years now the major political parties have converged as they both accepted neoliberalism as the guiding framework for economic and social policies. This has had at least two outcomes.

First, the major political parties have had to find some other

means to distinguish themselves from each other and have found it in history and culture. This has resulted in the so-called culture and history wars of recent decades, in which Australians have been exhorted to identify themselves and fight in these terms, rather than in terms of class, for example, which is a word we seldom hear these days. This change means that the 2023 referendum is more vulnerable to being exploited for political gain by the major parties than the 1967 one was, with Aboriginal people being the major losers.

Second, the adoption of those neoliberal economic and social policies has impoverished many white Australians at the same time as it has left them feeling that they have been deserted by the mainstream political parties, especially the Labor Party with whom many of them once identified. Not surprisingly, many of those people resent a form of politics that appears to talk a great deal about oppression and inequality in reference to race (and sex and gender) but hardly ever discusses what used to be signified by the word ‘class’. To make matters worse, these Australians, and the history they identify with, feel that they are being attacked as racist bigots rather than recognised as among those who have suffered major losses of one kind or another in recent years.

Another profound change since 1967 has been the demographic make-up of Australia. The non-Anglo-Australian migrant population has increased significantly, and yet public discussion of Aboriginal people’s post-1788 history is represented almost entirely in terms of a relationship between those of British descent and Aboriginal people. In varying degrees, the former enjoy the privileges that spring from the historical dispossession

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023 15

blackincbooks com

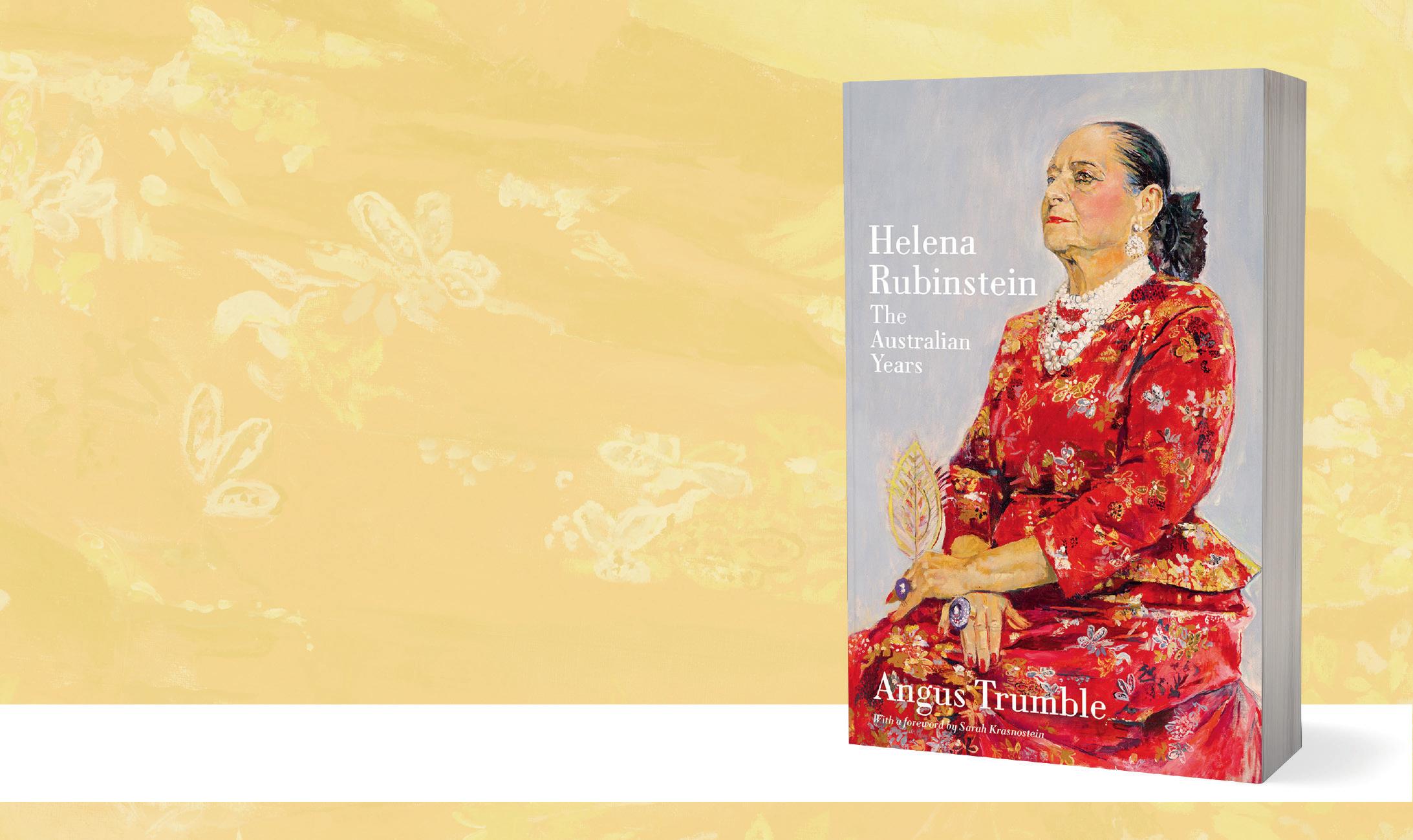

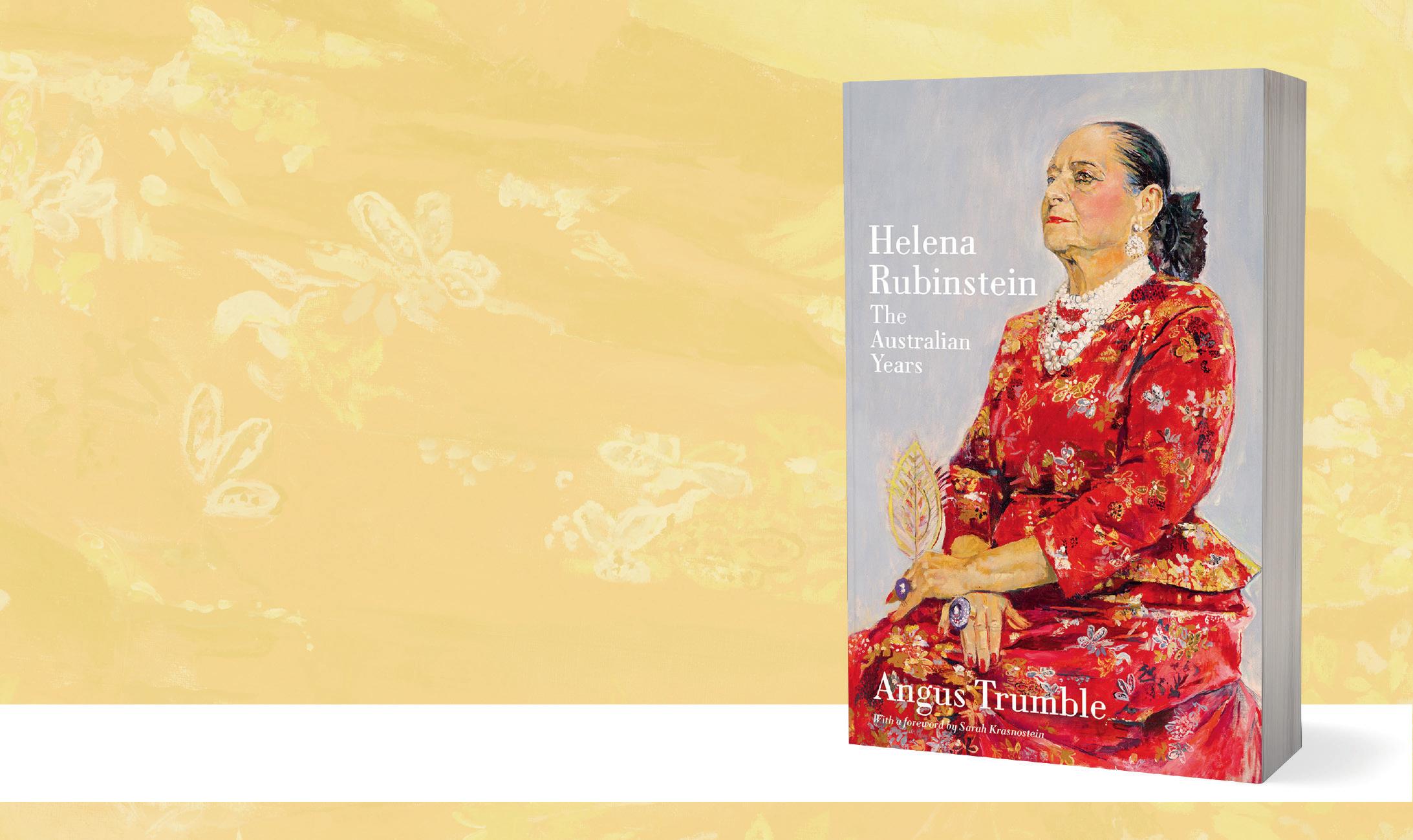

The captivating story of the first global cosmetics empire, the fascinating woman who built it, and the past she preferred to leave behind

Out Now

Take two!

Australian Book Review is delighted to offer a range of joint subscriptions with other Australian journals.

Eleven issues of Limelight (print only) plus eleven issues of ABR and one year’s digital access

$169

Four issues of Meanjin (print and digital) plus eleven issues of ABR and one year’s digital access

$170

Four issues of Overland (print only) plus eleven issues of ABR and one year’s digital access

$135

Two issues of Westerly (print and digital) plus eleven issues of ABR and one year’s digital access

$126

Four issues of Island (print only) plus eleven issues of ABR and one year’s digital access

$136

Four issues of Griffith Review (print only) plus eleven issues of ABR and one year’s digital access

$155

Available for Australian addresses only.

www.australianbookreview.com.au

and displacement of Indigenous people from the rich natural resources of this country, but relatively few of them have much sense that they might share some responsibility or obligation to help redress the legacies of the country’s black history, as they are seldom if ever included in political conversations about this matter.

Finally, the rise of new forms of media and the decline of older ones have contributed to an unprecedented increase in partisanship and a corresponding decrease in common public spaces. This makes it difficult for the campaigners for a ‘yes’ vote to counter misinformation and misrepresentation of the matters at stake.

This is all the more the case because of the increasing challenges to the notion of truth. A good deal of public life in any democracy rests on truth, but it seems we are no longer able to agree about how to establish what is true, as many people have become blind to proof. As Michael P. Lynch, an American philosopher, has put it: ‘Without a common background of standards against which we measure what counts as a reliable source of information, or a reliable method of inquiry, and what doesn’t, we won’t be able to agree on the facts, let alone values … When you can’t agree on your principles of evidence and rationality, you can’t agree on the facts. And if you can’t agree on the facts, you can hardly agree what to do in the face of the facts.’

The changes in Australia I have just been discussing are deeply woven into contemporary Australian culture, society, and politics. As a result, the influence they are having on the current yes campaign cannot be readily countered. Consequently, I find it hard to imagine that the ‘yes’ case will succeed.

I assume – or at least I hope – that in the next month or so the Labor government and their closest Aboriginal advisers will tackle what Freud would call a state of denial – the state of knowing but being unable or unwilling to acknowledge what you know – and reluctantly agree that it would best for the government to accept that the ‘yes’ case will probably lose, abandon the referendum for the foreseeable future, and seek to pass legislation that will create an Aboriginal voice to parliament.

If the government does this, it will undoubtedly disappoint the non-Aboriginal advocates and demoralise the Aboriginal advocates for the ‘yes’ vote. But perhaps the latter might be prompted to question their assumption that entrenching the Aboriginal voice in the Australian Constitution will ensure that their people will always be represented in Australia’s system of government. In reality, there is no such guarantee. An Aboriginal voice would remain, but any government could choose to ignore it. This is a discomforting truth about the position of a small, relatively powerless Indigenous minority in a settler colonial democracy. It means that their struggle for recognition, representation, and redistribution is a struggle without end. g

Bain Attwood is a professor of history at Monash University and co-author (with Andrew Markus) of The 1967 Referendum: Race, power and the Australian Constitution (Aboriginal Studies Press, 2007).

This article is one of a series of ABR commentaries on cultural and political subjects being funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

16 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023

‘Nasty, brutish, and banal’

The ploys of media moguls and politicians

Patrick Mullins

Media Monsters: The transformation of Australia’s newspaper empires

by Sally Young UNSW Press

$49.99 pb, 576 pp

In 1968, Rupert Murdoch was one step from acquiring his first international media holding, in the British tabloid The News of the World. That Murdoch was so close was a personal coup, given that his press ownership had begun sixteen years earlier with a much-diminished inheritance, largely based in Adelaide. To pull off the News of the World acquisition, however, Murdoch needed government approval to transfer $10 million Australian offshore. Speed, secrecy, and surety were pivotal, and in search of all three Murdoch went to John McEwen, the deputy prime minister and leader of the Country Party. The two had an enduring bond: McEwen had helped Murdoch buy his grazing station and family bolthole, Cavan, and when McEwen was appointed acting prime minister after the death of Harold Holt in 1967, Murdoch had argued in The Australian that McEwen should be prime minister in his own right. Now, in 1968, McEwen took Murdoch to the prime minister, John Gorton, who was also familiar with the young press baron. Gorton had briefly been lined up to work for Murdoch’s father in the 1930s and owed something of his present job now to the influence Murdoch had wielded when it became clear that McEwen could not remain prime minister.

McEwen and Gorton brought the matter to Cabinet a few days later. Treasurer Billy McMahon raised objections. An unequivocal departmental brief was McMahon’s main prompt, but another was his close relationship with Murdoch’s rival Sir Frank Packer, who had once promised to send Murdoch back to South Australia ‘with his fookin’ tail between his fookin’ legs’. Not this time. Murdoch’s path, with Gorton and McEwen behind him, was cleared. Politely ignoring a comment from Paul Hasluck that Murdoch was a ‘brigand’, Cabinet approved the transfer and Murdoch duly took his money offshore and got The News of the World – and then the world.

All the ingredients figuring in this small moment – press barons, politicians, an urgent acquisition, rivalries real and proxied, seamy deals and understandings – loom large in Media Monsters, Sally Young’s account of Australian corporate media history in the middle of the twentieth century. The sequel to Young’s lauded Paper Emperors (2019), this book focuses on how the newspaper companies of her earlier volume transformed themselves into multimedia behemoths in 1941–72. The title, drawn from a phrase by journalist and media executive Colin Bednall, refers to the sprawling empires that resulted from an unprecedented period of change

in the media industry, where the ‘monsters’ feasted on smaller competitors, staked out new territories, and took up new technologies. Yet the title performs a double duty of also describing the people leading those empires. The reptilian sense of contest and conquest, the paranoia and predilection for power and politicking, make these men – and they are all men – fearsome and compelling figures, even when the more cartoonishly thuggish ones (e.g. Packer) are set aside.

Rupert ‘Rags’ Henderson, for example, was a long-serving steward of the Fairfax family and The Sydney Morning Herald, yet he was also so frightening that journalists were rendered like the granddaughters who shook in their boots to meet him. Dubbed on his retirement the ‘Black Prince’, Henderson simultaneously nurtured the Fairfax empire and built his own in its shadow, with acquisitions – made always in a ‘personal capacity’ – of a litany of television stations and regional newspapers. The intent was to skirt rules that limited media holdings; the result was a sprawling corporation structured with interlocking entities that owned one another in fragments. The information Young compiles to depict this is a circuit board of controlled connections: John Fairfax Limited owned the Fairfax Corporation Pty Ltd, which owned Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd, which in turn owned a one-third share of Queensland Television Holdings Pty Ltd, which was also partowned by Amalgamated Television Services Pty Ltd, which was – ta-dah! – seventy-one per cent owned by the Fairfax Corporation Pty Ltd.

The proliferation of these structures was an answer to the rules introduced in the 1950s as Australia’s government and media barons reckoned with the arrival of television. Young recounts that reckoning with a wealth of unseemly detail and hardnosed insight. The press barons worked tirelessly to tip Labor from office in 1949, in part from fear that a re-elected Chifley government would establish a public broadcasting system in the mould of Britain’s, where the BBC reigned supreme. In the 1950s, they took obsequiousness to new lows by giving Prime Minister Robert Menzies free airtime on their radio stations, at peak listening periods, and pointedly denied the same airtime to Labor’s leader, Doc Evatt. In turn, the Menzies government appointed a royal commission into television that it stacked and then pre-empted by instituting a dual system of public and commercial broadcasting. Amid a self-interested campaign to accelerate the arrival of commercial television – ‘It’s time they gave us TV,’ ran a Daily Mirror headline – the press companies forged alliances to crowd out competitors and ensure they were the only viable candidates for the few commercial licences on offer. Undertakings freely given by the press barons about control and ownership were then rescinded, abandoned, or adhered to only in a black-letter law meaning. ‘There is no attempt to create an empire or anything like that,’ Murdoch said, during public hearings for the first licence in Western Australia, in 1958. ‘It would not interest me.’ Fine promises of what the press barons would do with those licences, too, were inevitably cast aside. Lectures by famous educationalists, demonstrations by leading scientists, programs that would be ‘wholesome, good, entertaining’, writes Young, were within a decade scarce on Australian commercial airwaves. What was plentiful was content that The Times of London called ‘nasty, brutish, and banal’.

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023 17 Media

Young depicts this unedifying process with clarity; her history demystifies and enlivens the tactical urgencies and strategic audacities that Australian media companies contended with and displayed at this time. She weaves around the more prosaic decisions – of premises, industrial relations, and capital-heavy investment in new printing plants and computers – their responses to broader social and economic changes, pointing sometimes to structural factors and at other times to personal influences. She lays bare the reasons for the demise of the 111-year-old Argus newspaper in 1954, for example, pointing to the poor decisions made by its owners, the British-based Daily Mirror group, and she explores the resurgence of The Age under editor Graham Perkin in the 1960s. Some pages of Media Monsters fossick well-excavated ground, but Young finds new bones. Her deep archival research, particularly through the Fairfax business records, suggests that Murdoch’s ultimate entry to the Sydney newspaper market in 1960 came about thanks to Rupert Henderson’s desire to help the young Murdoch on his way – a desire made benevolent by his belief that Murdoch, having purchased the failing Daily Mirror newspaper, would pose no competition to Fairfax and The Sydney Morning Herald. This, of course, was profoundly mistaken: the Packers, who received a gloating phone call from Murdoch immediately after the deal was sealed, knew just how competitive he would be.

What is sometimes heavy-going corporate arcana is also enlivened by an unexpected humour attained through tart juxtapositions. The first Gallup poll in 1941 registered fifty-nine per cent support for equal pay for men and women, Young

points out, and was reported on the same page as advertisements for stockings, lipstick, and curtain sets. The first two advertisements broadcast on new television channel GTV-9, in 1956, were for cigarettes and an analgesic linked to kidney damage and cancer: two products, Young notes dryly, that kill their consumers.

When Media Monsters opens, in 1941, the power of newspaper owners was at its peak: more than a million newspapers were delivered to homes in the morning, and a million more were sold after lunch at kiosks, street corners, train stations, and racetracks. By the end of the book, the decline of the newspaper business seems offset by the tremendous power wielded by many of the same owners through television. And yet, as Young closes, a very different future was ahead of them, and another transformation – perhaps for a sequel volume – awaits.

Young’s diligent and voluminous study sheds new light on the media companies still with us and reiterates with fresh force well-known conclusions. Among the most important is the role played by politicians in creating the massive media companies still with us. Wary of press power but hopeful of seeing it deployed in their favour, they unshackled the snarling monsters to rampage across the body politic. As John Gorton said, recalling how he had swung Cabinet in favour of Murdoch’s 1968 request, ‘I always liked Murdoch, and I started him on his way.’ g

Patrick Mullins is a Visiting Fellow at the Australian National University’s National Centre of Biography. His most recent book is Who Needs the ABC? (2022), co-authored with Matthew Ricketson.

ALCATRAZ

An illustrated anthology showcasing many of the most exciting poets writing in English across the globe.

18 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023

LEFTOVERS CASSANDRA ATHERTON TYPEWRITER PAUL HETHERINGTON poetry has a new home for more L ife B efore M an titles visit gazebobooks.com.au $34.99 inc. gst L ife B efore M an isBn 978-0-6454648-8-7 63 poets . hardBack . 22.5 × 14cm . 272pp . 100 + coL our i LLustrations

Self-inflicted wounds

A vindication of investigative journalism

by David Rolph

Justice Anthony Besanko’s dismissal of Ben Roberts-Smith’s defamation proceedings against a trio of mastheads – The Age, The Canberra Times, and The Sydney Morning Herald, at the time all owned by Fairfax – was a comprehensive victory for those newspapers. It was a vindication of their serious investigative journalism on matters of high public interest. And it was a devastating blow to the reputation of Roberts-Smith.

The stakes in this litigation were high. On one side was a highly decorated soldier, a Victoria Cross recipient – a person of high reputation in a country where the Anzac tradition is memorialised and valorised. On the other side was an exercise of the freedom of the press, to expose real or alleged crimes and abuses of power. At the centre of the dispute were allegations made against Roberts-Smith in a series of newspaper articles from June 2018 of the utmost seriousness. He was accused of murder, war crimes, bullying, and domestic violence. In response to the publications, Roberts-Smith elected to sue the newspapers and their journalists.

The articles themselves and the subsequent defamation trial may form the beginning of a reckoning with the truth of what happened during Australia’s involvement in the war in Afghanistan. Extremely serious findings were made in the Brereton Report (2020), but no criminal charges have yet been laid in response to them. The findings against Roberts-Smith may increase the political pressure for charges to be laid against him or others in relation to their conduct in Afghanistan. In the meantime, his defamation trial served, in significant respects, as a de facto war crimes trial. This was obviously undesirable but was an inevitable consequence of Roberts-Smith suing upon those allegations.

The trial was long, occupying more than a hundred days of hearings, and was protracted due to Covid-related interruptions. The proceedings were aggressively contested. More than forty witnesses gave evidence in the case. There were multiple interlocutory judgments. The final judgment, when it was handed down in early June, was the forty-first one in the proceedings.

The evidence was factually complex. Ultimately, though, the legal issues were straightforward. This was due to the defences pleaded by the newspapers.

The principal defence relied upon by the publishers was truth. Truth is a complete defence to defamation. The principled basis for this is that a person is only entitled to protect the reputation they deserve. If a person has enjoyed a high reputation undeservedly and a publisher tells the truth about that person, defamation law does not regard the person’s reputation as damaged. Rather, the person’s reputation is recalibrated down to the level at which it always should have been. This is, of course, precisely what happened to Roberts-Smith.

There were two variants of the truth defence relied on by the publishers in the case. The first was the straightforward defence of truth. Roberts-Smith had pleaded fourteen imputations arising from the articles. The newspapers were required to establish the substantial truth of each one of them in order to have a complete defence of truth. The standard is substantial accuracy, not strict or absolute accuracy. So minor errors of detail will not defeat the defence if the allegation is proved to be true in substance. Also, given that this was a civil proceeding – a claim for damages for defamation – not a criminal trial, the standard of proof was on the balance of probabilities, not beyond reasonable doubt. However, the seriousness of the allegations necessarily had to inform the cogency of the evidence Justice Besanko required to be actually persuaded that the allegations against Roberts-Smith were more probably true than not true. (This principle is known at common law as the Briginshaw standard, after an influential 1938 High Court of Australia decision.)

The newspapers were able to justify all but three of RobertsSmith’s pleaded imputations. To defend the remaining three imputations, they had to rely upon a statutory defence of contextual truth. Contextual truth is a fallback defence. It allows a defendant to have a complete defence if the substantially true allegations about the plaintiff outweigh the harm done to the plaintiff’s

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023 19

Commentary

reputation by the false allegations. Here, given the number and gravity of the allegations the newspapers had proved to be true, Justice Besanko readily found that the two undefended imputations of domestic violence and one undefended imputation of threatening a soldier would not further damage Roberts-Smith’s reputation. By this stage, Roberts-Smith’s reputation had been so diminished by the truth of what had been published about him that no further harm was done to his reputation.

The truth defence in this case worked. Had it not succeeded, the likely damages for Roberts-Smith, in addition to the legal costs, would have been crippling for the newspapers. Investiga-

The contours of the principal defences to defamation – truth, privilege, and comment – were settled in the nineteenth century. As they developed, courts decided against recognising a broadbased defence for publication to the world at large on matters of public interest. Legislatures introduced various forms of statutory protections directed at providing a measure of protection for such publications.

The focus of defences like statutory qualified privilege and the new public interest defence is on the journalists. To establish a defence of statutory qualified privilege, the defendant has to establish the reasonableness of their conduct in the circumstances of publication. The public interest defence requires the defendant to have a reasonable belief that the publication of the matter was in the public interest.

The effect of the newspapers relying solely on defences of truth in the Roberts-Smith case was that the quality of their journalism was not the focus of the trial. Had they pleaded a defence of statutory qualified privilege, the reasonableness of their journalists’ conduct would have been closely scrutinised over the course of the trial. Instead, by relying on truth, the intense focus of the trial was on Roberts-Smith’s conduct. Were the allegations the newspapers published about him true? It was a risky strategy for the newspapers, but it worked in this case. However, media outlets should not always have to run such a high risk in order to undertake serious investigative journalism on matters of public interest.

tive journalism is expensive and resource-intensive to undertake, but serves the vital public interest of holding power to account and informing the public about what is occurring. Its costs are compounded by the risk of defamation. This risk has to be managed pre-publication and, if that fails, has to be dealt with through defamation litigation, which is extremely costly. The estimated cost of the Roberts-Smith trial is $25 million. Media outlets have long agitated for greater protections to facilitate public interest journalism. In doing so, they are seeking at once to advance the public interest, but also, it should be frankly acknowledged, their own commercial interests.

These proceedings were conducted under the national, uniform defamation laws prior to the commencement of potentially significant reforms to them. From mid-2021, across Australia, except in the Northern Territory and Western Australia, the first stage of those reforms has come into effect. They include a reform that media outlets have been seeking for many years: a public interest defence to defamation. This defence closes a gap in the common law and brings Australian defamation law closer to the position in the United Kingdom, Canada, and New Zealand.

It is important to be clear about what the case decided. Clearly, it was not a criminal prosecution. There were no charges and no conviction. The case did not concern Roberts-Smith’s liberty but what can be lawfully said about him. By deciding to sue for defamation, Roberts-Smith himself put his reputation in issue. He asked a court to determine whether it was defamatory to say of him that he was a murderer, a war criminal, and a bully. A court found that those allegations were true. Those findings were not provisional: they were final determinations following a full hearing of the evidence. There may or may not be an appeal, and any such appeal may or may not be successful. All that is in the future and is contingent. The possibility of a successful appeal does not detract from the fact that Justice Besanko’s judgment finally determines the issues in the case and what can now be lawfully said about Roberts-Smith.

Sometimes, allegations are so serious and so public that a person may think that they have no choice but to sue for defamation. But ultimately, suing for defamation is a choice – and a risky one, as Roberts-Smith learned publicly and to his great cost. The reputational harm ultimately done to Roberts-Smith was self-inflicted. g

David Rolph is a Professor at the University of Sydney Faculty of Law. He is the author of several books, including Reputation, Celebrity and Defamation Law (2008) and Defamation Law (2015). From 2007 to 2013, he was the editor of the Sydney Law Review, one of Australia’s leading law journals.

This article is one of a series of ABR commentaries on cultural and political subjects being funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

20 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023

Angus Campbell, Ben Roberts-Smith, and former Governor-General Peter Cosgrove in Iraq, 2015 (Office of Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, gg.gov.au via Wikimedia Commons)

Ostalgie

Examining a vanished world

Sheila Fitzpatrick

Beyond the Wall: East Germany, 1949–1990

by Katja Hoyer Allen Lane

$35 pb, 485 pp

by Katja Hoyer Allen Lane

$35 pb, 485 pp

Katja Hoyer, born in East Germany, was four years old when, on the eve of the state’s collapse in 1989, her parents took her to the Berlin Television Tower and she gazed spellbound from its rotating visitors’ platform at the protesters and police cars gathering in the square below. In this book, Hoyer sets out to show an East Germany that amounted to more than just the Berlin Wall and the Stasi. That nowvanished, would-be-socialist world is presented critically, but also with empathy and the undertone of affection you may feel for something that mattered to people you love.

I started Beyond the Wall with high expectations that were at first somewhat dashed. Yes, East Germany had good child care, support for the advancement of women, cars for the people (Trabants, affectionately called ‘Trabi’), regular paid holidays at resorts for workers, a fair amount of comradeship, and even some rock musicians, as well as offering much more opportunity for upward mobility than most countries in the West. Yes, it had deutsche Qualitätsarbeit, that is, a level of workmanship and technical finish that was the envy of the socialist world. And yes, this all coexisted with boring sanctimonious leaders (first, Walter Ulbricht, then Erick Honecker) who seemed either old before their time or just old; the country was kept under surveillance by the secret police, whose reach and size (proportionate to population) were without parallel; and a Wall had to be built to keep the population in. But, while some of this might be a shock to those who know East Germany only via Anna Funder’s Stasiland, it isn’t too much of a surprise to anyone with any acquaintance with the GDR before 1989.

But forget those reservations, because the story becomes fascinating as it gets into the 1970s and 1980s, and the reader starts to grasp Hoyer’s underlying sense of a country with the odds stacked against it but a lot of resourcefulness in dealing with its situation. East Germany (officially the German Democratic Republic, or GDR) was created, in the face of a Soviet preference for a neutral united Germany, out of the postwar Soviet Occupation Zone in Germany that remained as a rump

after the American, British, and French Occupation Zones were united, under US and British tutelage, as the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949. Industrial and energy resources were concentrated in the West, not the East; and on top of that, West Germany had the benefit of generous financial support from the United States. East Germany’s backer was the Soviet Union, but it was a parsimonious sponsor even after it had got over its postwar zest for stripping Germany of any economic asset that could be shipped east on a train. The bright lights and employment opportunities in the West were as much part of its lure to Easterners as democracy; and brain- and population-drain was a constant problem that the Wall was built to solve (a solution, well described by Hoyer, that created other problems).

Dependent on the Soviet Union for energy, and largely cut off from the world market for other necessary products, East Germany showed ingenuity in finding alternative sources. For example, when a desperate shortage of coffee developed in the mid-1970s, the solution was a deal with Ho Chi Minh to establish coffee plantations over a large area, with the GDR’s investment repaid with half the crop. Lacking aluminium for their Trabants, the GDR used Duroplast – a mix of synthetic resin, cotton waste from the Soviet Union, and paper – and apparently it worked.

Their greatest ingenuity was in establishing more or less covert relations with West Germany to solve some of their worst economic and financial problems as Soviet support became increasingly unreliable. This was not just a product of Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik of the early 1970s, but continued under successive

West German chancellors (after the discovery of an East German spy in Brandt’s office ended his chancellorship in 1974). There was the cash-for-people scheme, by which the West German government paid East Germany to let political prisoners and would-be emigrants leave (by 1983, the GDR had sold 33,755 people to the West at an average price per head of DM 95,847). Foreign currency stores and special mail-order catalogues enabled

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW JULY 2023 21 History

Street art graffiti painting ‘The Kiss’ by Dmitri Vrubel, East Side Gallery, 1991 (photograph by Joachim F. Thurn, German Federal Archives via Wikimedia Commons)

West Germans to help both their relatives in the East and the East German state by sending West German money and gifts.

All this produced what Hoyer describes as an almost cosy behind-the-scenes relationship between West and East German leaders that annoyed the Soviet Union, which warned the East Germans several times to avoid ideological contamination (not incurred, apparently, in the separate game of détente it was playing

A black hole

The airbrushing of George Orwell’s reputation

Michael Hofmann

Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s invisible life by Anna

Funder

Funder

with the United States). Then, in the 1980s, the Soviet Union pulled the plug on the energy supplies, with scant regard for the welfare of its socialist ally. If Leonid Brezhnev was unsympathetic, Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika liberals were even more so, and fresh admonitions followed against the East German version of ‘openness to the West’, which was openness to West Germany on the basis of a shared sense of Germanness. When Gorbachev abruptly cut East Germany loose in 1989, causing the fall of Honecker and the Wall, he was not just going after a ‘reactionary’ leadership, but one that was trying to assert some independence of the Soviet Union.

When the GDR collapsed at the end of 1989, the result was different from what East German leaders in the years of sub rosa amity might have hoped. As West Germany’s negotiator put it bluntly, it was ‘not the unification of two equal states’, but rather, an opportunity for East Germans to become citizens of the Federal Republic, that is, a straight-out West German takeover. There were pluses and minuses for East German citizens in this. Their new country was richer; on the other hand, they were the poor relations, their qualifications often undervalued and jobs hard to find. There was more democracy and less surveillance (although, in Hoyer’s telling, most people had got used to the Stasi, which in latter years was into surveillance and admonition rather than terror and punishment). Their new country was less provincial but in many ways more demanding: in Hoyer’s words, East Germans had ‘had a fair amount of money and time on their hands without having to worry too much about having to make the most of it. As a result, they spent a lot more time socializing and enjoying leisure pursuits.’ Capitalism meant less leisure, more anxiety, and harder work.

Some sullen resentment was noted in the East after the Wende (East Germans’ preferred term for unification, implying a switch to a new direction), and the term Ostalgie had to be coined to describe nostalgia for the old East German way of life. Most people did not want the GDR back. But it was not nothing that they had lost, and that’s one of the two thoughts Hoyer wants to leave with her readers. The other, addressed mainly to Germans, is that the GDR was not just a historical wrong turn that led to a bit of a detour before getting back on the main road, but part of German history. g

Sheila Fitzpatrick is the author of many books, including The Shortest History of the Soviet Union (2022), and ABR’s new Laureate.

Hamish

Hamilton

$35 pb, 407 pp

Wifedom is both an immovable and an irresistible book, an object and a force. Anna Funder, the author some years back of the bestselling Stasiland (2003), has written another great and important narrative of oppression and covert suppression, in this case of the first Mrs George Orwell, Eileen O’Shaughnessy (1905–45). The oppression and suppression are or were the work of her liberal and emancipatory husband – the nearest thing we have these days to a lay saint –and of his six (male) biographers. While nowhere a nasty book (what the Americans would call ‘mean’), it’s a kind of St George and the six dwarves. What’s strange is the persistence of the old bromides. In a recent Guardian review of D.J. Taylor’s Orwell: The new life (2023) – the biographer’s second go-around – Blake Morrison refers to ‘the practical Orwell’ and ‘the complaisant Eileen’. He wouldn’t have said either thing if he’d been able to read Funder’s new book.

As the title would suggest, Wifedom amplifies effortlessly into the question of what it is that allows clever men, productive men, brilliant men, impractical men, to produce work, if not their invisible, misunderstood, neglected, and then effaced wives. To men, whether husbands or sons, brothers or lovers, old men or New Man, it will be more or less painful reading. To women, it will, I dare say, be shockingly familiar. When I read it – short sentences, plain language, and slashing conclusions – I was reminded that Anna Funder once trained as a lawyer. It has the lawyerly virtues: urgency, mobility, tenacity, consequence.