Susan Pierotti

Welcome to the first issue of Stringendo online! Ideas about broadening the reach of Stringendo, adapting to modern technology and making the magazine more attractive and accessible for readers and potential subscribers have been discussed between National Presidents and the National Editor for at least ten years.

The onset of Covid lockdowns meant that all of us learnt to improve (begin?) our online skills. We learnt how to get the information we wanted via the internet. After lockdowns, this seemed the ideal time to move Stringendo from expensive paper printing (which for at least 30 years has eaten up over half of AUSTA’s budget!) to free digital access.

Concertino ad Feb21_Layout 1 21/02/2022 8:11 AM Page 1

We now have the capacity to include weblinks in every article. Over the next year, we will be working to improve mobile phone readability. We are planning social media campaigns that will align with Stringendo advertisers and articles. And it will be now issued four (yes, four!) times a year. For those, like me, who love a glossy magazine to use as a show-off item on the music stand, there will still be a printed issue once a year.

Now, here’s the interactive part – we need your feedback! My wonderful Stringendo Board of Nicole Strohfeldt (President), Louise Booth (Graphic Designer) and Mina Grieve (Social Media Manager) have churned out ideas each month for over a year. However, a ‘good idea’ is only a good idea if it works for everyone. We need to know if you like it online, if you like the look of it, if it is easy to access, easy to read … All bright ideas will be considered!

Happy reading!

Next year AUSTA turns 50! We want to celebrate this achievement so the theme for the entire year, 2025, will be AUSTA.

If you have a great story about how AUSTA has transformed your teaching, playing, connecting etc. we want to hear about it. If you are turning 50 in the same year, we would like to interview you. If you have some fabulous reminiscences about AUSTA over the last 50 years, please share them with us.

The National Conference will also take place in 2025. Any articles about previous AUSTA conferences will be enthusiastically accepted. Deadline for the next issue is Friday 31 January 2025.

is a different voice in the string orchestra market. Owned by Saraband Music, Concertino produces inviting editions of music for school and community orchestras at very reasonable prices. Score & full set of parts. To order, call Patrice on 07 3129 0537

Available now:

C001 Patrice Connelly - Somewhere a River, for string orchestra $66

C002 John Jenkins (arr. Connelly) - Suite in g minor, for string orchestra $77

C003 Patrice Connelly - Weazel Waltz & Weazel Tango, for string orchestra $80

C004 William Brade (arr. Connelly) - Suite in G, for string orchestra $77

C005 Johann Hermann Schein (arr. Connelly) - Two suites, for string orchestra $77

C006 Graeme Webster - Get the Red Dress Out, for string orchestra $88

C007 Graeme Webster - Dugongs & Pelican Rock for string orchestra $99

C008 Graeme Webster - The Owl on Crane Street & Gedachten for string orchestra $70

C009 Patrice Connelly - Visiting Day at the Factory, for string orchestra $66

C010 Caroubel/Praetorius (arr. Connelly) - Gavottes from Terpsichore (1612) for string orch $66

C011 Johannes Ghro (arr. Connelly) - Two intradas (1603) for string orchestra

$55

should do it!”

Paige Gullifer

Adelaide at the beginning of January might draw the height of summer to mind, that muted time of year between New Year and the frantic beginning of the year anew. But while most of Australia’s orchestras are in their summer slumber, the members of the Australian Youth Orchestra are just getting started on what’s often quoted as the highlight of their musical year: National Music Camp

From across the nation, hundreds of Australia’s emerging musicians, artistic administrators, composers and writers will make their way to the University of Adelaide for two whirlwind weeks of all things music.

Now approaching its 77th year, National Music Camp, known affectionately as NMC, is a watershed of the Australian musical year. It’s been the foundation of friendships and even marriages and launched the careers of numerous aspiring musicians. Most importantly, it’s a place where passionate musicians, from all walks of life, come together to celebrate music. While alumni of the program occupy orchestras in Australia and across the world, for some, the program is a great way to

solidify their relationship with music as they move onto other fields.

AYO alumna and MSO violinist Monica Curro has been appointed Creative Director of NMC in 2025. Drawing on both her personal experience of NMC and her international network of artists and mentors, Monica has assembled a highly anticipated program.

“It’s an incredible experience,” Monica says, “You will step into an immersive world of orchestral and chamber music for two of the most intense and inspiring weeks you will ever have, guided by the best conductors and tutors from Australia and around the world. You will gather mentors, colleagues and friends you will have for the rest of your life. I met my best friend in the world at the National Music Camp in Adelaide in the ’80s.”

In 1948, two teachers, John Bishop and Ruth Alexander, held the very first NMC in Point Lonsdale, Victoria on an actual beach in actual tents. After that first camp, as they shook the sand out of their shoes, could they have anticipated that NMC would one day host “giants” of Australian music? From John Curro AM MBE, Richard Gill AO and Lindley Evans to James Judd (ex-chief NZSO), Umberto Clerici (Chief QSO), Ariel Zuckermann (Israeli Chamber Orchestra), Alex Briger (Chief AWO) …

NMC participants are assigned to one of two full symphony orchestras (the Bishop and Alexander orchestras named in honour of the founders) or a string orchestra, and everyone is involved in chamber music opportunities. Here they’ll prepare two full

concerts’ worth of repertoire, often rehearsing from the early morning until late at night. This is no ordinary music camp – these are the cream of the crop of Australia’s young musicians, auditioned and handpicked. They are here to learn and grow, make mistakes and bounce back from them, but most of all, they act, rehearse and play as if in a professional ensemble. In between rehearsals, musicians eat together, relax together, embark on the traditional tutors versus students cricket match and take in everything Adelaide has to offer. The effects can be lifechanging, as Sophie Rowell, Artistic Director of the Melbourne Chamber Orchestra and director of the Brislan Chamber Orchestra at NMC in 2024 reflects.

“It was through AYO that I really found that I couldn’t live without being a violinist, without having music

in my life. [At NMC] I get so inspired being around not only the amazing young musicians, but also the energy of the young musicians and their inquisitive natures, their willingness to learn – you give them a challenge and the way that they’ve surmounting that challenge day by day by day.”

Of course, it’s not just a camp for performers. My first NMC was in 2020, and it was one of the very last large-scale musical programs I was involved in before the onset of the pandemic. I was part of the Words About Music program, which is now known as Media and Communication. For two weeks, I met and worked with world class music critics, presenters, orchestral librarians, radio hosts and of course, musicians. It was an eye-opening foray into a wider musical world, one I’d never encountered before, and the first time I’d had the opportunity to so overtly combine my two passions, music and writing. Although it was almost five years ago now, that camp is so firmly etched into my mind. While I honed my skills in presenting, writing program notes, interviewing musicians and composers, it was just as much about the friends I made.

I remember hearing the finale of Sibelius’ Second Symphony being whistled by audiences as they left. A fellow participant from another orchestra said, ‘Professionals have nothing on that kind of energy.’

Then in 2022, I had the opportunity to return to NMC again, this time in a performance capacity as the sole saxophone player. It’s not often I get the opportunity to perform with orchestra, and this audition opportunity was not one I could pass up. Following the pandemic’s restrictions, NMC temporarily migrated to Melbourne, and two weeks of music making became one. But the spirit and joy of NMC

certainly wasn’t affected; in fact, the joy of reuniting and the value of music making was only enhanced.

It was at this camp I played with a now AYO regular, violinist Hanuelle Lovell. It was her first of three NMCs, trumped by regulars with seven or more to their name. We performed Rachmaninov’s Symphonic Dances together, and she describes the significance of this moment.

“My first NMC was in 2022. I missed out on a lot before I finally got the opportunity to go – for various reasons – so when the opportunity finally aligned, it was really exciting. We’re playing Rachmaninov’s Symphonic Dances at Queensland Con this year and I’m unbelievably excited to play it because it was the first major work I ever did with AYO, at NMC. I just remember it being the most electrifying feeling ever walking off that stage after finishing it. It was just amazing. It’s just such a celebration and every time I get to the end of NMC, I’m like, ‘Oh no, I don’t want it to be over!’ because it feels like you pour, everyone pours so much of themselves into it. I think that’s why everyone gets the NMC blues afterwards because suddenly, where’s all this passionate energy going to go? And I do think people do try and take it back into their daily lives, which is really just a beautiful way to start the year.

“But there’s something special about those two weeks at the start of the year that sets everything off on the right foot. It’s absolutely amazing, honestly. It feels in some ways like school camp, where you go down in the morning and you have breakfast with everybody ... but I think the nice one of the nicest things on camp is just walking back from rehearsals at the end of the day with people in your orchestra and chatting about how the day’s gone, and I think that’s just a really nice atmosphere, and the best way to get to know people. Sometimes you just end up chatting to some random person you never chatted to before in the orchestra and then suddenly

you become friends with them because of this one conversation you had that one time after rehearsing. I think that’s the nice thing about NMC – it has so many little gems that you take away and you’ll remember for a long time.”

And to potential auditionees, Hanuelle offers this advice: “I think everybody should do it! I auditioned so many times before I actually got in, and when I finally did, I got to experience so many different programs and have so many valuable experiences. The audition process also really prepares you for anything, and the exposure to challenging music is really important. This year, I had my first professional audition and one of the excerpts that came up was one that was in my very first AYO audition. I couldn’t play it at all at the time, and so it was a gratifying feeling being able to go, ‘Oh! I can actually play this now!’

“You can imagine how much you change as a person across your time with AYO. They’re like a family, and they see you grow up and that’s so beautiful and really makes you not want to ever leave! I think AYO just feels like a safe space where you feel so cared for, and every person in the orchestra is always valued.”

Paige Gullifer is a saxophonist currently completing her Bachelor of Music (Honours) at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. She has performed with the Australian Youth Orchestra and participated in several programs in the United States. Paige is a regular program note and copy writer for the Adelaide and Queensland Symphony Orchestras, and has enjoyed writing for AYO, Ensemble Apex and New York Public Radio’s New Sounds.

Nicole Strohfeldt AUSTA National President

Welcome to our first digital copy of Stringendo!

We are excited to bring you this new version of our journal and we hope that you will enjoy interacting with the online format. There are many advantages to the digital spread: namely, the ability to link you directly to websites, videos and other online spaces, as well as the obvious benefit that your Stringendo magazine is now available to you whenever you can spare a minute to scroll. We hope that you will enjoy this fresh, online edition of Stringendo, and that the integrated features will allow you to explore topics with ease. We welcome any feedback on our new format.

We will now be able to archive our Stringendo magazines on the AUSTA website, providing a rich source of information (and perhaps even a walk down memory lane) for our members.

At the time of writing, we have just farewelled our magnificent AUSTA Touring Artist for 2024, and AUSTA patron, Barry Green. In a mammoth tour spanning 27 days, he has spread his joy and love of music far and wide to AUSTA audiences. We are grateful for his wisdom, enthusiasm and willingness to try anything (including Bundaberg Rum), and from all accounts, we have left him with a heart full of wonder and delight.

Our national conference committee has been meeting behind the scenes since last December and we are excited to be bringing the 2025 Conference back to Sydney, at the beautiful venue of the Sydney

Conservatorium, 10–13 July 2025. As it’s also AUSTA’s 50th anniversary next year, it promises to be an inspiring conference, full of joy and celebration. Mark your calendar now and stay tuned for more announcements in the coming months.

As always, I thank the state committees and their incredible presidents for their endless enthusiasm. Australia’s string community is in great hands, and I am grateful for the mountain of volunteer hours that are poured into our organisation by these generous people. If you would like to join your local state committee as a metropolitan or regional representative for 2025, I encourage you to contact your president now. The Annual General Meetings will be held towards the end of the year and an extra pair of hands is always welcome.

Wishing you a wonderful end to the year.

Molto AUSTA!

Our latest 2023 edition of the Sydney Directory of Music & Speech Teachers is now available on-line free of charge for all music lovers. You can now keep up to date with all the exciting opportunities for young performers and also gain access to Australia’s most prominent Music and Speech Teachers !

Choosing the right teacher is without doubt the most important decision a parent will ever make when embarking upon a musical education for their child. Students and parents are also invited to stay in tune with the many exciting opportunities available for young musicians by subscribing to our FREE musicteachers.com.au email news broadcasts.

View the Directory today at – simplebooklet.com/2023sydneydirectoryofmusicspeechteachers

For further information contact Catherine & Warrick Dobbie –Email: contactus@musicteachers.com.au or Phone: 0412 642 048

TAmy Phillips President, AUSTA Q

he first half of 2024 was a gratifyingly and rewardingly busy time for the AUSTA Q community. The year commenced with our flagship annual Reading Day and AGM on 4 February. It was a delight to see so many local, regional and interstate attendees. Being part of the collegial and enthusiastic energy, and hearing and playing the new works, was the most inspiring way to commence the year. The quality and number of new compositions presented by our local composers was exceptional! Bundaberg also hosted a Reading Day on 18 February for their local AUSTA members and teachers in their community.

It was my pleasure to attend the AMEB Qld 2024 Performance and Awards Ceremony on 8 March to see AUSTA Strings Award (Qld) 2023 Nathan Niessl receive his award. Congratulations, Nathan!

We were honoured to have Ed Le Brocq as the keynote presenter for the AUSTA Q Mini-conference, held 13–14 April. Ed’s presentations focusing on ease, joy and glory (comfort, happiness and success) in string playing and teaching, and presentations by Dr Bernardo Alviz (intermediate Double Bass), Raquel Bastos and Loreta Fin AM (AMEB Viola Series 2), David Deacon (Scales – are they ‘weighing’ you down?), Gyorgy Deri (The Popper-Code), Jonny Ng (Juggling a Portfolio Music Career), Natalie Sharp (Fundamentals of Left-Hand Technique) and Dr Anthony Young (Musicianship in the Instrumental Setting) provided excellent professional development and inspiration leading into Term 2. The first day of the Mini-conference concluded with an informative and fascinating interactive forum session with the panel of Dr Bernardo Alviz (double bass), Gyorgy Deri (cello) and Natalie Sharp (violin and viola) facilitated by Theo Kotzas. The second and final day concluded with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for the delegates orchestra to rehearse Triptyque for String Orchestra by Yasushi Akatagawa conducted by Michael Patterson.

At the time of writing this, the AUSTA Q committee is making final preparations for AUSTA International Touring Artist 2024 Barry Green’s time in Brisbane (10–14 July) and Bundaberg (15–18 July) and for the Concerto Championship and Strings Festival (27–28 July). Preparation is also well underway for Brisbane and regional events later in the year; keep a look out for details via the AUSTA website and newsflashes.

Wishing everyone all the very best as the year continues and we look forward to seeing you at the upcoming AUSTA Q events!

Bethany Nottage President, AUSTA SA

On2 June, 10am–12 pm, we held our Student String Ensemble Workshop in the Performing Arts Centre at Seymour College. Georgina Price and I facilitated and conducted the groups and the students enjoyed performing their pieces to their families in a concert to conclude.

On the afternoon of Sunday 2 June, string players and teachers gathered at Seymour College to play through some new string ensemble music written by Australian composers. Martin Butler conducted this Repertoire Reading Day and we enjoyed playing through many new pieces and were accompanied by Stuart Robison.

We had our term 2 Beginner Adult String Players Workshop on 16 June, kindly hosted by Kathy Wozniczka. Of the three pieces we played, two were original compositions. ‘Swoon Tune’ was written by Robyn Handreck who also conducted, and ‘Gentle Giant’ was written by Samantha Zwolak who helped by playing violin.

On Friday 26 July in Hartley Concert Room, AUSTA Patron Barry Green worked with the Adelaide University Elder Conservatorium undergraduate classical, jazz, vocal, instrumental and education students. They experienceed Barry’s unique insights in the Inner Game of Music Workshop and Coaching Masterclass, and heard Barry play some works on double bass and learn principles in Mastery of Music.

On Saturday 27 July, Barry ran a Music Mastery workshop covering his books, Bringing Music To Life and The Mastery of Music. Prince Alfred College kindly allowed the use of their chapel from 1:30 to 5pm, with this workshop designed for all musicians, music and instrumental teachers, as well as Year 12 and tertiary students interested in improving their own sound and performances.

IAndrew Schellhorn President, AUSTA Vic

t is again a pleasure to reflect on the recent achievements of AUSTA VIC and celebrate the positive impact that this body has had on teaching and learning.

In committee member news, Helen Holt resigned earlier in the year. After serving on the AUSTA Q committee from 1982, Helen moved to Melbourne in 1990 and served as AUSTA VIC Treasurer and State President. Helen fondly remembers starting the String Orchestra festival with Julie Hewison and being prominent in the instigation of the cello spectaculars. We thank her for her wonderful work.

Eight Victorians and an ex-Victorian (now based in Perth) attended the 2024 ESTA Conference in Porto in March. Committee members Diana Wuli and Marcel Trussell-Cullen both presented at the conference and were outstanding. Yes, we did all eat too much and enjoy ourselves!

In May, Warwick Stengards, the Australian/Swedish freelance conductor based in Vienna, led a group of mainly string teachers in a full two-day workshop on the principles of conducting.

The String Performers Festival held in June was another success, with a healthy group of committee members and many performers. Special thanks to James de Rozario who once again ensured the event’s smooth operation and StephanieJane Lewendon-Lowe for again being the official accompanist. The performers were delighted to receive their newly designed sashes and reports. This July, we are full engaged and excited for the arrival of Barry Green, the American bassist and author. Our own Andrew Moon studied with Barry at the University of Cincinnati in the 1980s. Andrew is to be Barry’s personal driver while he is in Melbourne.

This year’s Paul McDermott Violin Scholarship was also held in July and was adjudicated by Kirstin Kenny. We sincerely thank Kirsten for taking so much time to make each performer have a positive experience and play to their best. The 2024 Paul McDermott Violin Scholarship winner was Audrey Chen. We look forward to seeing and hearing Audrey play at an AUSTA VIC event in the future.

Reviews Editor Mary Nemet interviews Australian violinist Chris Kimber.

MN: Chris, our history goes back a long way. What are your earliest memories of playing violin and who were your inspirations?

CK: It all began at 316, Sandy Bay Road, Hobart, when I was 10 years old. The celebrated violinist, Ginette Neveu, performed the Sibelius concerto in the Hobart Town Hall on 10 August 1948. That was a memorable experience. Afterwards, Neveu came to our home and I played to her with my brother William on piano. Later, when my family moved to Melbourne, I went to the first National Music Camp directed by Professor John Bishop. It was there I joined you, Mary, in performing Sibelius’ Symphony no. 2. Professor Bishop invited three of us to perform as soloists in the Bruch Concerto: I performed the first movement, Gillian Rosefield the second and Graham Wood the third.

MN: Who were your teachers and what are your recollections of them? Did any stand out in particular?

CK: In 1954, Max Rostal, the eminent violinist and distinguished teacher, toured Australia for the ABC. Rostal awarded a scholarship to enable the most

gifted young violinist in Australia to study with him in England. You and I were jointly awarded that scholarship! The irony is that neither of us found study with Rostal ideal. Not all teachers, no matter how celebrated, fit the needs of every student. You moved on to a distinguished career under the auspices of Arthur Grumiaux and Isaac Stern, and I moved on to study in America. At the Julliard School, New York, I studied with Ivan Galamian and later Oscar Shumsky. Shumsky was not only a great violinist but also a wonderful teacher who made everything easier to play, including works as difficult as the Bartok Solo Sonata.

MN: Do you think it essential for young musicians to seek further tuition overseas, or are there now enough fine teachers in Australia?

CK: Australia is still isolated geographically and musically. The excitement of studying overseas surrounded by great violinists like Zukerman, Perlman and Kyung Wha Chung raises your standards and inspires you to achieve more. For example, I was greatly inspired when hearing Milstein, Stern, Francescatti and Morini all performing together in a Carnegie Hall concert. Another memorable experience was hearing the Cleveland Orchestra performing a Schubert symphony conducted by George Szell. I later had the privilege of playing to George Szell who offered me a position in the New York Philharmonic. A thrilling experience was playing in a scintillating performance of Schumann Symphony no. 2 with the exciting Scherzo conducted by Leonard Bernstein at the Casals Festival, Puerto Rico.

MN: In your long and distinguished career, there must be many highlights, but what are some of the most memorable?

CK: Being appointed Assistant Concertmaster of the Baltimore Symphony and performing as soloist with the orchestra. Touring Europe and Israel with “Soloists from Marlboro” along with Rudolf Serkin, Jaime Laredo, Leslie Parnas, and

Peter Serkin. Recording Beethoven’s 8th and Bach Brandenburg Concerti with Pablo Casals at Marlboro. Performing as soloist with the Boston Pops Orchestra conducted by Arthur Fiedler and Joseph Silverstein. A concert with Jack Benny in Symphony Hall, Boston. (Dressed as a stagehand, I brought a music stand to the front of the Boston Symphony. Jack Benny handed me his Strad, and I played the soloist opening of the Brahms Concerto, with Jack Benny glaring menacingly at me!) Being appointed Associate Professor at Oberlin College. Accepting the offer of Artistic Directorship of the Australian Chamber Orchestra along with Chairman of the String Department and Senior Lectureship at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. (I subsequently resigned from the ACO but following a rapprochement, I performed as Artistic Director of the Australian Chamber Orchestra and soloist on tours for Musica Viva.) Joining the Primrose Quartet with Oscar Shumsky, Harvey Shapiro and William Primrose for concerts in Japan. (A magical experience! Oscar Shumsky had complete command of his instrument and was able to create intense musical and emotional impacts in the masterpieces we performed.) Performances as soloist with the Adelaide, Melbourne, Sydney and Queensland Symphony Orchestras with celebrated conductors including Walter Susskind. Touring with distinguished pianist Gerard Willems in Asia and Australia – the most rewarding concerts for me.

MN: Looking back, what would you tell your 12-yearold self?

CK: While becoming an accomplished violinist is a worthy goal, the importance of a thorough education at a good school with the opportunities for making friendships with fellow students is invaluable in youthful years. Most distinguished musicians are also gifted in other areas. However, a musical career can provide a remarkable life. I have been extremely fortunate to make music with many great artists, ensuring that my life has been uniquely fulfilling.

Mary Nemet

Gopinko is a name that deserves much greater recognition among string players.

Born in 1891 near Mogilev, Ukraine, little Jascha was tutored at home before winning a competition to study in Moscow where he became a pupil of Auer, later entering Pawel Kochanski’s virtuoso classes at the Warsaw Conservatory.

However at age 22, to avoid being drafted into the Russian army, Gopinko set sail in the Orvieto, reaching Melbourne in 1914, a year of continuing civic turmoil and conflict in his homeland. Partly to avoid conscription, one can surmise that he also left because of the savage pogroms against Jews. In cities like Odesa and Kyiv, thousands of Jews were killed while the police stood by, under the Tsarist regime of the Romanovs. The families of Heifetz, Milstein and Elman must have been similarly affected by this recurring social terror.

Who knows what heights Gopinko may have achieved if he had stayed? A wonderful player by all accounts, he may have reached those of the other Jascha – Heifetz. His musical circle included luminaries like Artur Rubinstein, Igor Stravinsky and Prokofiev. World War I robbed Gopinko and his colleagues of any hope of a performing career or teaching at the Conservatorium. They all emigrated. Fluent in Russian, German and French, Gopinko fled to Australia but spoke no English. With no opportunity to perform, he moved to Sydney where he washed bottles in a factory, and then to Kurri Kurri, a mining district near Newcastle. His application for Australian citizenship was for some time denied, since his presence in the area was regarded as suspicious. Gopinko became a citizen, after several years of attempts, in 1930.

In the surrounding coal mining towns of Bellbird, Cessnock and Maitland, there was no shortage of music. Irish and Welsh émigré miners had brought their traditional choirs, brass bands and instruments with them, forging bonds in the community.

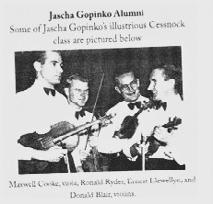

with mistrust as a Russian immigrant, possibly even a spy, Gopinko’s violin playing soon prompted fellow miners to ask him to teach their children. Among the first of these were Ernest Llewellyn and Nelson Cooke. Cooke remembered him as ‘an extraordinary man, with tireless energy, enthusiasm and dedication’.

Because the instruments were readily available, he formed a mandolin orchestra composed of miners and began to teach on violin, viola and cello. He founded the Cessnock Symphony Orchestra, touring the region as its conductor. Local audiences cheered them on. Visiting professional soloists like oboist Joseph Post were engaged.

In time his students began to win prizes at eisteddfodau and gained leading positions in orchestras and chamber ensembles at home and abroad. Here is an irony. Since Gopinko was barred from joining the Sydney Symphony Orchestra because he was a foreigner, the orchestra was soon replete with his students.

Although at first viewed

His undoubted earliest success was his student, Ernie Llewellyn, who went on to become concertmaster of the Sydney Symphony. Llewellyn later reflected that Gopinko had played a role in Australian string playing comparable to that of Leopold Auer in Hungary and Russia; indeed, the entire musical world. “He had miners with their big, gnarled hands playing Mendelssohn concertos on the banjo and mandolin – he was quite amazing.”

Born in Kurri Kurri in 1915, Llewellyn, the son of a Welsh miner, began lessons with Gopinko in 1934

and joined the Sydney String Quartet as a violist. Other students who joined the SSO’s ranks were Ron Ryder, Ron Cragg, Donald Blair, Errol Russell, Maxwell Cooke on viola and Nelson Cooke on cello. By then Gopinko and his wife Rebecca (to whom he had taught the cello) had moved to Sydney where he rented a teaching studio at Paling’s music store, teaching very long hours. However, he still taught at Maitland twice a week.

Rebecca cooked meals for students and frequently boarded them free of charge. Gopinko explained, “You don’t play well unless you feel good.”

Other students included Beryl Kimber, Chris Kimber, Ronald Woodcock, Errol Collins, Marjorie Hystek, Leslie Chester and Brian Blake. The three Sumner girls, Dorothy (cello), Roma (viola) and Heather (violin), all in the SSO, were among his pupils.

Chris Kimber reminisces:

“Many years have passed since my childhood, but I clearly remember those few months I spent in Sydney studying with Jascha Gopinko. I went along Hunter Street with my sister Beryl to Palings Studios where Gopinko taught and sat in on Beryl’s lessons. He taught me little folk melodies; one such piece was a beautiful little Russian air. Gopinko got me to play it with all my soul, and he would accept nothing

less. After those few months in Sydney – I must have only been aged around ten – I flew back to Hobart by myself, played the Russian air to my father and he was bowled over by the new expressive feeling in my playing!

Adult strings

Chamber music

Classical Guitar

Folk Mandolin

Also, I remember many trips in the tram to Gopinko’s home in Double Bay, where all his protégés played chamber music together and enjoyed a stimulating time. Mrs Gopinko acted as hostess. I have great memories of those chamber music evenings and Gopinko’s great influence.”

Leslie Chester, aged 22 in 1936 and Concertmaster of the TSO, had this to say in the Hobart Mercury. “Under Professor Gopinko I learned not only the concerto repertory but also chamber music, conducting and how to teach.”

When Paling’s Building was demolished, Gopinko moved his teaching to his home, continuing chamber music evenings every second Thursday, according to another student, Phillip Silver. The coalminers still wanted to learn, so they hitched a ride on the coal train once a week for lessons. Phillip studied with Gopinko for seven years from the age of 18 and considers him his greatest mentor. Lessons consisted of scales, Kreutzer studies, concertos, sonatas and salon pieces. His students were brought up in the solid Russian school of violin playing, as he had been. Phillip recalls, “If you had done the work, the lesson had no time limit, but if you hadn’t, the lesson was over immediately. As his last student of the day, he drove me down the hill to the nearest bus stop in his big old 1940 American Packard car, turning the motor off and just coasting down – quite dangerous!”

Students like Gillian Bailey-Graham attest to his fine teaching. “I studied with Jascha Gopinko for five years, travelling from Newcastle every Saturday during my last two years of school before moving to Sydney to study with him full-time. He was an amazing teacher and beautiful person. I was never afraid of him. He was always encouraging and kind while still demanding. Mr Gopinko has been an inspiration for my teaching to this day.” Teaching in Gillian’s grandparents’ building in Cessnock, miners’ children flocked to the door. Gopinko kept long

hours, as did the miners. Gillian remembers him as a handsome man with dark hair, dark eyes and fine expressive hands that sought to bring out the essence of the music, but he also had a mischievous sense of humour.

A picture emerges of a remarkable man, dedicated to music, devoted to his students and determined to make the world a better place.

[I am indebted firstly to Patrick Brislan (former AYO Alumni Coordinator) for initially piquing my interest in this amazing string teacher. Several former students of Gopinko enthusiastically shared their reminiscences; among them, Gillian Bailey-Graham, Chris Kimber and Phillip Silver. Anna Cooke shared recollections and photos of her husband, eminent cellist Nelson Cooke’s time with Gopinko. The Coalfields Historical Association also shared data. My gratitude to all who contributed to this project.]

Mary Nemet’s extensive performing career has taken her across Europe, Asia and Australia. Her studies with luminaries such as Arthur Grumiaux and Isaac Stern have enlightened her teaching practice. A long-time AUSTA member, she was Stringendo’s National Editor for five years and is currently its Reviews Editor.

Edwina Kayser

From Deborah Greenblatt, USA: I was discussing the art of practising with one of my little students, and I asked her what she could do to make her piece better. She confidently replied, ‘Put in repeat signs’.

The author of the article, ‘South Australian State Music Camp’, in the last issue of Stringendo (Vol. 40/1), was not Agnes Weinstein but Jennifer Watkins, a MPhil student at the Elder Conservatorium of Music. Her thesis topic is ‘The History of the South Australian May Music Camp: 1962-1987’. She is Administrative Assistant to the Music Staff at Concordia College and is Secretary of the SA State Music Camp Association committee. Stringendo apologises for the error and for any grief caused.

On a Sunday in January, chamber music enthusiasts travel from all over Australia to the picturesque alpine village at Mt Buller in Victoria. The Chamber Music Summer School begins with lunch, the first meal in a week of gourmet dining, catered for by chef Ben Davies from High Country Food Co. The afternoon is spent settling into comfortable ski lodge accommodation, and then it is into the music. Dusting off those holiday cobwebs, string chamber music ensembles ranging from trios to sextets begin their intensive week of rehearsals. In the evening, participants are treated to an informal concert presented by tutors in the intimate surroundings of the Benalla Ski Club lounge.

The timetable from Monday to Friday has been developed with assistance from participant feedback over many years and contains the essential ingredients for the development of chamber music skills. The days can begin with an early morning walk along a beautiful alpine track or an informal yoga session; however, the first scheduled activity is a warm-up/technical class with your instrument group. It’s an ideal place to discuss specific technical issues, gain insight into a warm-up routine, stretch in preparation for a long day or play a massed viola version of Puccini’s ‘Nessun Dorma’ not to be outdone by a gorgeous celli rendition of ‘Danny Boy’.

The next two sessions (1.5 hours each) are dedicated to rehearsing with your ensemble. In one of these sessions, participants are coached by a member of the excellent tutorial team. To gain the most out of this experience, participants are encouraged to apply in pre-formed groups and to have chosen their repertoire. The lengthy tutorial time provides an opportunity to study a movement in depth.

Following a well-earned lunch break and a reacquaintance with the coffee machine, participants enjoy a one-hour ‘ad hoc’ session. The purpose is to play chamber music with others you may not have met before. Apart from adding to the camaraderie of the summer school, this session is a wonderful opportunity to play in larger ensembles and explore new repertoire or revisit old favourites.

OFFERS A SELECTION OF VIOLINS, VIOLAS, CELLOS & BOWS TO SUIT STUDENTS AND PROFESSIONALS

OFFERS A SELECTION OF VIOLINS, VIOLAS, CELLOS & BOWS TO SUIT STUDENTS AND PROFESSIONALS

Another 1.5-hour rehearsal with your group precedes the daily cocktail concert. Frequent performance opportunities for participants are one of the most successful aspects of the week. The cocktail concerts expose everyone to a wealth of repertoire and provide performers a chance to put into practice advice they have received from tutors in a very supportive and relaxed environment.

Expert Repairs and Restoration undertaken. Bow Rehairs & Repairs carried out on the premises.

Expert Repairs and Restoration undertaken. Rehairs carried out the premises.

Dinner is a gourmet affair. Chef Ben has been preparing delicious cuisine for participants since 2014. His dedication and ability to cater for every dietary requirement combined with an easygoing

INSTRUMENTS AND BOWS BOUGHT AND SOLD

INSTRUMENTS BOWS BOUGHT AND SOLD

222 NEW SOUTH HEAD RD. EDGECLIFF, SYDNEY 2027

208A NEW SOUTH HEAD RD. EDGECLIFF, SYDNEY 2027 & FAX: (02) 9363 0203

PHONE & FAX: (02) 9363 0203 irwinviolins@bigpond.com www.irwinviolins.com.au

irwinviolins@bigpond.com www.irwinviolins.com.au

disposition ensure the kitchen is always a happy place to be, particularly if rehearsals become intense! The summer school has always been very fortunate to receive support from the local Mansfield community. For more than 15 years, chef and vocalist extraordinaire Maria Lurighi delighted our tastebuds with dishes that were as creative as the musical offerings. In more recent times, Ann Jaggard, a remarkable supporter of the Mt Buller and Mansfield communities, has contributed enormously to the success of the week, not only through her connections but also her unselfish and tireless hard work.

After dinner, the tutors present a concert or forum. Since its inception, the summer school has attracted some of Australia’s finest chamber musicians as tutors. Their extraordinary generosity of spirit, sharing of musical ideas and dedication to the week has been a key factor in the success of the summer school. The evening forums have varied from a resident contemporary composer discussing their work to a candlelit performance of solo Bach cello suites in the beautiful alpine chapel. There have been discussions about Alexander technique, an opportunity to sing Bach chorales and play a massed ensemble version of the Mendelssohn Octet.

An evening at Mt Buller is never complete without taking the time to enjoy a sunset from the balcony. Once the scheduled activities have concluded, it’s time to join friends over a Brahms sextet or two, perhaps saving the Schubert quintet for Tuesday night.

Other highlights for the week include time on Wednesday afternoon to explore the incredibly beautiful alpine region. A range of activities is organised by our hardworking manager, David Dore, including nature walks or a swim in the Delatite River.

Musical activities of the Summer School culminate with the presentation of two public concerts in the resonant acoustic of the Alpine Chapel. The first concert on Friday evening is presented by the tutors and the second concert on Saturday afternoon provides participants with an opportunity to play one movement of a piece they have been studying throughout the week.

The summer school concludes with another delicious meal and time to reflect on all the wonderful happenings of a week filled with music, friendship and fun. Many repeat attendees leave the mountain counting the weeks until the next Chamber Music Summer School at Mt Buller.

The summer school began in 1985 under the artistic directorship of Janis Laurs. A person of extraordinary vision, energy and artistry, later joined

by the Australian String Quartet, Janis created and supported an institution that has lasted for nearly 40 years. Original committee members Roy Bull, Fiona Rixon, Jenny Johnson and Jim Vizard found the perfect location and developed the format of a seven-day residential string summer school for participants consisting of amateur, tertiary student and professional string players. AUSTA generously supported the summer school by helping to spread the word through advertisements and an article written by then National President, Philip Carrington. Forty years later, Jim Vizard continues to help ensure the summer school’s longevity. A key component of the school’s success is that it is run by a voluntary committee who attend as participants, nurturing

the joy of music making in a totally supportive environment. As a registered charity with tax deductible status, the summer school maintains a scholarship gift fund which regularly supports tertiary music students with career aspirations in chamber music.

The summer school has a rich history of offering outstanding tuition and chamber music performances through the services of some of Australia’s finest musicians and teachers. The Australian String Quartet (William Hennessy, Douglas Weiland/Elinor Lea, Keith Crellin and Janis Laurs) played a significant role in establishing and supporting the school. As a participant, I will never forget an extraordinary week when the ASQ delighted us with a performance of a Haydn Op. 20 quartet every lunchtime followed by a late Beethoven quartet after dinner! Spiros Rantos with Ensemble I colleagues (Brachi Tilles, Tor Fromyhr, Gwyn Roberts and Simon Oswell) have been great supporters. Bringing an international flair, Simon also delighted us by inviting his group, The Capitol Ensemble, from Los Angeles. Tutors from Queensland have made a significant contribution to the summer school with artistic director Michele Walsh and her wonderful colleagues from the Merlin Ensemble (Margaret Connolly, Patricia Pollett and Sydney cellist Rosemary Quinn) attending ten times. The summer school has been supported by many other outstanding musicians such as Caroline Henbest, David Berlin, Christopher Martin, Peter Tanfield, Miki Tsunoda and the Flinders Quartet (who initially attended as students), and composers including Ross Edwards, Graeme Koehne, Lisa Lim, Richard Mills, Ian Munroe and Larry Sitsky.

Last year, the summer school was delighted to welcome back Elinor Lea as director and provided the opportunity for a family reunion with her brothers from the Vienna Philharmonic, Benedict and Tobias Lea. They were joined by William Newbery, David Berlin and Anna Pokorny, resulting in a very happy school and culminating in a magical performance of Schoenberg’s Transfigured Night.

Next year CMSS is delighted to welcome back long-time friend and supporter of the summer school, Wilma Smith, as artistic director. The dates are 19–26 January 2025; applications open in late August. Tertiary musicians who have an established string chamber music ensemble are invited to apply for funding to attend at cmssbuller@gmail.com

If you would like more information on next year’s Chamber Music Summer School, go to https://cmss.org.au/2025/

Edwina Kayser is a freelance professional violinist and teacher who enjoys performing frequently with Orchestra Victoria and Aequales Ensemble. She feels privileged to teach and have the opportunity to share a love of music with a wide community.

Grace Ah-quee

“I loved every bit of it! … We all work together to create something fabulous at the end.”

“I love Perth Summer camp! It’s the highlight of the year for me”.

Young music lovers from early level to advanced youth instrumentalists have a place at Perth Summer Orchestra Camp, 13–24 January 2025. PSOC has created a pathway in their holiday program for all levels that’s fun and engaging. The Junior, Summer and Brilliant Strings orchestras will run 13–16 January, followed by the Advanced Baroque Orchestra, 20–24 January.

The program started in 2011 and has become so popular that there are now five orchestras for string players as well as places for winds in our top level Baroque skills orchestra. Social and foundational friendship skills are an important part of our group philosophy.

Our musical home has always been at Moerlina School in Mt Claremont, expanding to Quintilian school next door. The PSOC Baroque Summer School is held at Aquinas College in Salters Point.

Perth Summer Orchestra Camp’s 25 extremely experienced staff are professional musicians with a strong background in education. Conductors, specialist tutors, assistants and operations staff with orchestral skills cater to all the needs of the different level players.

Junior string players who’ve been playing for two years or more work with inspiring and caring conductors in the Junior Ensemble. Middle level players of Grade 2–3 standard join the joyous Summer Strings with our founding conductor,

Daemon Clark. More experienced players of grade 4–5 standard focus on style at our Brilliant Strings level or go up to the advanced level Baroque Summer School orchestra, aimed at Grade 6 to AMusA standard for a uniquely in-depth week with Music Director Grace Ah-quee and Australian Baroque’s Artistic Director, Helen Kruger. Masterclass and solo opportunities are also available.

All PSOC places are available without audition except solo and masterclass placements at Baroque Summer school. Auditions for advanced solo and masterclass places close in November with general enrolment (no audition) closing early December.

PSOC is very interested in providing places to regional players and we are grateful for AUSTA’s sponsorship in helping to provide this.

All applications and information can be found at www.psorchcamp.com/

Grace Ah-quee studied violin in Sydney. She currently works as a violist in the Perth Symphony Orchestra, WA Philharmonic ballet orchestra and as a principal for Fremantle Chamber Orchestra. She is Conductor and Music Director for Allegri Chamber Orchestra and has worked as a conductor for the Western Australia Youth Orchestra for 20 years. Grace has created and performed in many interactive concerts for children and informative pleasure concerts for adults. Grace is Music Director of Perth Summer Orchestra Camps, including its Baroque specialisation camp.

As the lights in Hamer Hall dimmed, we lifted our instruments and all 45 pairs of eyes looked directly at me, eagerly anticipating the first familiar chords of Eine Kleine Nachtmusik. They rang out with precision and unity. We had become a finely tuned ensemble; however, we hadn’t started like that …

Morning – beginning

It was during the staff briefing the afternoon before the MYO Summer School began when all 15 ensemble leaders and conductors were introduced. The sheer number of young musicians, who were forgoing a week in the sunshine, became apparent –820 in total and from across all of Victoria! This was some mighty thing the MYO had going.

We came to the first morning, anticipating some of what was to come but not really knowing. Excited instrumentalists lined up en masse to receive their lanyards and raced inside to discover their ensemble positions. Music stands (with a wide variety of stabilities!) were unfolded and, with instrument in hand, each member of the Rowell Chamber Orchestra sat down. Some chatted wildly with their neighbours (and continued to do so for the rest of the week), others sightread all the music in their folder at the loudest possible volume, while the rest sat quietly, not quite sure of what was to come. In all honesty, I also fell into the last category. I could see string players who came up to my shoulders and others who towered over me. Turning this gaggle of young musicians into a unified ensemble was going to be no mean feat.

We began by tuning. At this stage of the summer holidays, the instruments had a less than ideal range of pitches, and the resultant noise was absolute cacophony. Not for the last time that week, I spoke as loudly as I could and waved my arms in the air like one of the inflatable tube people at a used car saleyard. Silence reigned, followed by my first directive of the week – “Please tune softly so that together we can all tune carefully and accurately.” It was not the last time I would say/shout/ exasperatedly sigh this directive during our time together, but it was our first foray into becoming a united team – each of us gaining awareness beyond our own bow on the string.

It is very hard for the person at the back of the violins to hear their counterpart in the cello section. That is the case in any orchestra, let alone a string orchestra of nearly 50 young players. As the week progressed, so did this awareness. With an array of playing levels and ensemble experience, one of the things I hoped all would benefit from was an increased cognisance of their own playing in relation to those around them. Utilising a warm-up of scales gave us the opportunity to focus on intonation and blend of sound. Often, we explored dynamics through each scale, these variations not only being led by me but by individuals and by sections throughout the orchestra. My favourite was the laser-like attention paid to our lone double bass player as her ‘section’ led the orchestra through her dynamic variations.

We tackled a wide array of repertoire through which we could touch on many aspects of playing. There were technical challenges, rhythmic complexities and ensemble conundrums. These challenges are further compounded when the ensemble is directed by someone who is also playing, as I was. It means that my ability to hear exactly what was happening always is somewhat hampered. I was most grateful to the wonderful tutors who helped

guide the musicians through the week. Their tutorials were invaluable not only to aid in the development of the parts, but also to create a team bond within the sections, noticeably stronger after each session. This was something I tried to actively foster further through various exercises during our rehearsals. This was a string orchestra of rather large proportions, but my aim was to ensure that each musician would feel like they were a valuable part of the team. Finding unity and identity within their sections was important in fostering that.

Another aspect I was particularly keen to hone in on was playing in the same part of the bow. With so much focus on the music in front of us and the technical demands of our left hands, I find (in orchestras of all sizes and ages) that this skill can be overlooked. To maintain that focus without constant reminders, I was rather insistent that bow distribution instructions be written in their parts, although, without fail, that did lead to a sound so synonymous with pencils and wire stands – a chorus of pencils dropping to the ground.

As a string orchestra, one of the distinct advantages in a long week such as this, when minds (of all ages!) are starting to wander, is that we can stand up, our cello colleagues notwithstanding. When tired minds were flagging, the heat was soaring, wills were waning and all in the room were dreaming of things outside our four walls, there’s nothing like the iron will of an orchestra conductor that makes everyone move their chairs out of the way and come to attention for the practice performance they didn’t know they had in them! Each day we were becoming more harmonious, more homogenous and more like a team.

And so, it was finally our chance to showcase our efforts for the week. The warm-up room was by turns giddy with excitement and hushed with expectation. By now, this group were no longer strangers to each other, and I noticed the more experienced helping others with their instruments, checking that everything was in order. As we walked onto the stage, my heart was in my mouth, and it would remain there for the rest of the performance. I knew we all knew what to do – in theory! As it turned out, I needn’t have worried … except for one bit for which I gained at least four new additions to my increasing numbers of grey hairs, but that’s a story for another day … The care and the responsibility each musician took with everything they played was overwhelming. More than anything, the unity of spirit and the willingness to be a valuable and accountable part of a group shone through.

Mine was just one of 15 ensembles and this magic had happened with each one of them during this week. Music isn’t just good for the community – it creates a community, and it creates people who are willing participate in it, no matter what path they take to get there.

Thank you to MYO and all those who create opportunities for this to happen for our young musicians.

[Ed. The 2025 MYO Summer School will take place at the University of Melbourne Southbank Campus, 6–11 January, with seven string orchestras (Preliminary to Grade 8) and two symphony orchestras (Grade 7 and above).]

For more information see https://myo.org.au/programs/ summer-school/2025-summer-school-residential-camp/ Sophie Rowell studied with Beryl Kimber Alice Waten and the Alban Berg Quartet. After winning the ABC Young Performer’s Award in 2000, Sophie founded the Tankstream Quartet, later named the Australian String Quartet. Previously Concertmaster of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, in 2023 she was appointed Artistic Director of the Melbourne Chamber Orchestra. She is the Head of Chamber Music (Strings) at the Australian National Academy of Music.

Concerto by Leatherwood Bespoke Rosin is your luxurious, super-premium rosin for intense soloistic playing. Designed for the soloist, power, focus and projection are prominent with minimal dust and sound deterioration.

After years of rosin recipe refinement for string players all over the world, the Leatherwood Bespoke Rosin team have worked to create the ultimate rosin recipe for the Concerto Soloist and International Competition Performer. When performing in these settings, there are even more demands on the rosin such as projecting the sound to all corners of the concert hall, conveying warmth of sound up close and far away, and the ability of the rosin to endure a long performance with minimal deterioration to the sound quality right through to the last note!

The result is a rosin that offers a very powerful and clear attack on the string, with the string vibrating at it’s maximum capability from the very beginning of the bow movement. This rosin improves sound endurance, overall projection, power, with a warm undertone.

Available online or through your desired string retailer

“Concerto by Leatherwood Bespoke Rosin is truly extraordinary; I’ve never used anything like it! So potent but also refined, so pure. Just a little bit of touch up every morning makes the hair feel renewed. It has been a real joy using it, and I highly recommend it!”

James Ehnes - International Soloist Violin: “Marsick” Stradivarius of 1715. Image © Benjamin Ealovega

Margaret Hoban

“The most amazing thing to me about RSSC is the musical camaraderie that is evident from the very beginning of camp. The age or ability of each camper does not matter. In this beautiful setting, everyone is having a great time playing music with their friends. The week at camp is simply magical.” (Mary Sorlie, conductor, Greater Twin Cities Youth Symphonies, Minneapolis, USA)

Where did it all start? In 1989, Lynne Price, an adult violin student based in the north-west of Tasmania enlisted the help of three Launceston string teachers, Rosemary Evenhuis, Jenny Kershaw and myself, to set up a string camp to give local young players a “tribe” to belong to plus an opportunity for professional development for string teachers. Originally intended to run for five years, it was to be a fun and challenging time for both students and teachers alike. The five years ran out 30 years ago but an organic, intuitive, living creature which continues to evolve remains. The foundation principle was to continue to make learning music the joy and wonder it should be. I needed to create something that people were excited to be part of – including me.

Originally, funding for the camp came from the first venue, Marist College in Burnie, along with local and national arts groups and private sponsors. It quickly became self-supporting to provide the flexibility we felt was essential to fit with our vision of what we wanted it to be. This has proven to work over the years and has developed an abiding culture of independence and resilience. Participant growth coincided with a move of venue to Camp Clayton, a much larger facility which offered the opportunity to include adult students and development of a more serious and focused ethos.

James Anderson, the new camp Director in 2023 and camp participant from nine years old writes: “This was the great tribal gathering. These were

my people, all in one place at one time. Through beach walks, campfires, swimming, games, wildlife spotting, eating, I have learned life lessons, gained role models and met some of the most interesting people in the world. These people became my second family, and my best and longest friends. Funnily enough, the camp was also about music, which enriched and enhanced all of the above. Music is firstly about connection and community. At string camp, you are always doing with others; there are no solos and not even a hint of competition. So often competitions, auditions, exams and assessment turn people away from playing and loving music. The risks are too high. At string camp, there’s nothing to lose. Music isn’t just about getting the right notes. The character, feeling and expression are primary objectives of the camp orchestral experience where the technical attention becomes merely a device to achieve these things in this atmosphere.”

The string camp is the result of my efforts to discover a way of teaching and presenting an instrument as an adventure, a giant puzzle, transfixing and utterly absorbing. Music is a wonderful teacher – it teaches honesty and integrity, shows you how your brain works and demonstrates how we all learn in our own ways. True creativity comes from authenticity and fearlessness; so many want to learn this –students, tutors and conductors. Sight reading is a critical part of camp experience. Music is not sent out prior and everyone comes to a level playing

field. Camp conductors and tutors are high level professionals with very wide orchestral backgrounds who also have a passion for supporting community music. Many have significant overseas and national experience. Camp participants witness professional musicians at play, reading and enjoying often unrehearsed chamber music with much laughter and jokes for all to share. I don’t give much direction to camp musical staff. I encourage them to bring their own special passions and interests to the camp which has built the unique flavour of each camp over the years. As electives, we’ve included scales competitions (hotly contested), Chinese music, Celtic fiddling, jazz, free improvisation, Pilates for string players, Dalcroze workshops – a wide spread of different aspects of music with a community flavour that people can elect to be part of, or not. The choice is each individual’s.

RSSC today is a much larger, thriving camp in a lovely area of the Bass Strait, a week-long residential camp for all ages and ability levels which is attracting staff from the mainland and the US. Would-be tutors and conductors are interested in how the camp runs and how the model works. What are we doing to support its ongoing success? One factor has definitely been the banning of mobile devices and access to social media which had begun to detract from the quality of the camp experience. This gave us back of lot more than we really understood we had lost. Conversations flourished, as did participation in physical activities and just joining in.

Susie McMahon, an adult string student camp participant from 2009 writes, “The annual Residential Summer String Camp is a wonderfully immersive experience, not only musically (that is a given) but also an intensive week of sharing meals, conversations, fun and activities with like-minded creative people of all ages and backgrounds. We all have one thing in common: the love of making music together. There is the euphoria of arriving at the seaside site, with friendships renewed, meeting conductors and tutors and having that first playthrough of the week’s music, with occasional hilarious results. The camp’s organisational structure is similar from year to year, but there are always exciting new and different things to look forward to. Tutorials and specialist workshops are keenly attended. Almost as soon as it’s begun, time has really flown and RSSC is over for another year as we perform our final concert, pack up and say our goodbyes as we head home. Everyone is a bit tired

and sore, but on a real high and already making plans for next year.”

String camp as an organisational entity doesn’t strictly exist. Somewhat like that musical village of yesteryear, Brigadoon, it rises up at the same time each year because of the love people have for it. It has survived a couple of near endings, but each of these has given an opportunity for a new and better way forward. Because the camp has no staff, property or external funding, relying solely on the goodwill of people who love it, it has an enduring flexibility and is very adaptable as a result. Those characteristics are the camp’s great strength and advantage and underpin its long-term success. It’s not about short-term goals but rather engaging people of whatever age for the rest of their lives.

Visitors have often remarked that the camp is unique to Tasmania and couldn’t be replicated elsewhere. But music is a universal language and the desire to be involved is compelling. What I have done is to find a community and build on its strengths, and not be frightened of challenging the status quo. A realistic approach and desire to add opportunity and value to an exchange of energy which will be of benefit to teachers and students is a fundamental principle, as is the maintenance of financial independence which supports flexibility and freedom of choice. Each camp generates reflection and is treated like a good student. What has worked? What hasn’t? Were campers engaged and happy with the activities provided? Did tutors meet and match expectations? Can our offering be improved, and if so, how? How do we keep the camp accessible in an unequal world for those who might find it beyond their means? Planning for the next camp begins as the old one finishes.

We will keep going as long as it’s possible to keep a residential, inclusive and mixed age camp going. The camp will transition to other people over time, and there will be change and challenges to maintain the ethos and culture of the camp experience. In the end, music must exist in, and of, love to have life. Music is participatory, not just a spectator sport. For more info, go to https://www.lyco.org.au/rssc/ about-the-rssc/ Margaret Hoban studied violin in Minnesota before moving to Australia. She has a thriving private studio and conducts the Launceston Youth and Community Orchestra. She is the cofounder, long-term camp Director and Musical Director of the Residential Summer String Camp in northern Tasmania.

James Pensini

One of the key evolutions of the last decade at Sydney Youth Orchestras has been the introduction of what we affectionately call our “Open Programs”. These Open Programs, including Summer School (13–18 January 2025) and Winter School (14–19 July 2025) roughly mirror the regular SYO structure of orchestras, but are condensed into a week and do not require an audition for entry; hence, “Open”. Summer and Winter Schools are designed for students 6–18 years of age.

The intensive week-long model allows students from all around New South Wales, and indeed nationally, who simply could not be in Sydney every weekend for orchestra rehearsal their chance to “meet their tribe”. Through the generosity of SYO donors, SYO is also able to help offset the cost to many of these families.

Each new Summer and Winter School is structured based solely on enrolments and is completely separate in terms of ensemble placement from the regular SYO program. Alongside orchestral rehearsals, tutorials and concerts, every member of Summer and Winter School will also sing each day with some of the leading vocal instructors in Sydney.

A typical orchestra structure normally looks something like this:

Yellow Strings – AMEB Preliminary–Grade 2 or equivalent

Orange Strings – AMEB Grade 2–3 or equivalent

Pink Strings – AMEB Grade 4–5 or equivalent

Purple Strings – AMEB Grade 6–7 or equivalent

Green Symphony Orchestra – AMEB Grade 7–AMusA or equivalent.

The orchestras work with the outstanding regular SYO conductors, tutors and staff and special guest conductors like the inimitable SYO alumni, Stephen Chin, at the start of this year. Where possible and practicable, SYO also tries to include professional development for educators in the Summer School program.

The other Open Program that SYO runs is called the Youth Orchestral Camp (YOC) where we take four SYO orchestras (Peter Seymour Orchestra, Richard Gill Chamber Orchestra, Symphonic Wind Orchestra

and Western Sydney Youth Orchestra) to a location in regional NSW and invite players from all around NSW and nationally to join one of the orchestras for a week of intense music making including rehearsals, tutorials and multiple performances. In 2025, the Youth Orchestral Camp (YOC) will be held in Armidale, NSW, 23–27 April. This program will be most suitable for players roughly AMEB 6th Grade or equivalent or above, aged 12–24.

The Open Programs are, of course, rooted in SYO’s ethos of inclusivity, excellence and community. They serve as fun catalysts for personal and artistic growth, empowering students to unlock the boundless potential of their musical aspirations, no matter how long they have been learning an instrument.

We look forward to seeing your students and potentially you (!) at one of our SYO Open Programs in 2025.

Go to www.syo.com.au for more information on SYO’s Summer School programs and weekly programs. For any specific enquiries, please feel free to contact james.pensini@syo.com.au

James Pensini is a former State and National Board member of the Australian Band and Orchestra Directors Association. He is the founding conductor of the Western Sydney Youth Orchestra, conducts the Peter Seymour Orchestra, and is SYO’s Head of Orchestral Training and Artistic Programming.

At Alex Grant Violins, our bows by master Austrian bow maker Thomas Gerbeth are now sold out! Three new bows are expected in spring; book now to secure your trial. We are also excited to announce that the playful and dynamic Greenline cases for violin and viola from Jacob Winter in Germany will soon be in stock. Constructed using non-toxic glues, these cases feature eco-friendly cotton and velvet interiors, reducing the cost of our music making on the environment.

Saraband Music has more of Louis Bégin’s Classical bows for sale. Violin, viola and cello available and more can be ordered if these have been snapped up. $2500 each plus packing and postage. These bows make string playing a pleasure.

Kickstart your 2025 music program with the Simply for Strings Workshop. As our string teachers prepare for some well-earned rest, so do the many instruments that have spent a year in the hands of an excitable student. With years of experience in assessing, repairing and setting-up instruments for budding and established music programs, the team of luthiers at Simply for Strings are preparing for their biggest season of school repairs yet. Last year saw hundreds of instruments make their way through our workshop, and we expect this year to be even greater! In 2024/25, our focus is on making the repair process as simple and streamlined as possible, both for string teachers and their admins. With every instrument being assessed by a member of our workshop team, and lovingly quoted

by Jacqueline, our Education Manager, you are guaranteed a smooth experience that is uniquely tailored to the needs of your program. If you would like your instruments repaired and returned to you asap, get in touch with Jacqueline as spots are limited.

Pirastro’s newest addition to our Perpetual string line is the Perpetual Cadenza for violin, with a warm and deep tone with a great wealth of colour and noticeably easy to play. For all cellists, let’s discover the new Flexocor Deluxe cello string, inspiring ease and comfort. And don’t forget our innovative new KorfkerRest® Luna® shoulder rest for viola. Its unique design and materials allow the viola an astonishing freedom of range, accuracy in response and trueness of timbre. Its ingenious snap-in system means personal adjustment is only one click away.

Kreutzer’s 42 Etudes are well-known as thorough study material for violinists and violists. Twofold Media is pleased to announce that we’re now working with Fintan Murphy on a Kreutzer Etudes website, with demonstrations and teaching points, due for release in 2025. Meanwhile, Violin Bow Technique+ and New Sevcik Variations by Fintan are still your go-to subscription sites to answer your technique and musicianship questions. From only $6 per month.

Rainer Beilharz

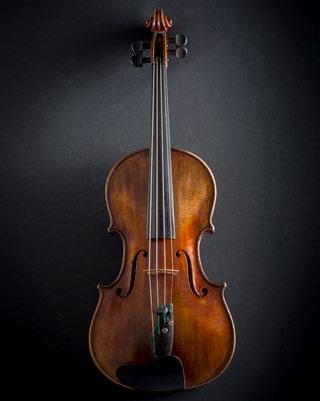

To anyone with an interest in violin acoustics, a proposition is quite often put along the lines that Stradivari didn’t have these tools available to him, so what makes them important now? My answer would be: He was certainly able to judge pitch (representative of stiffness) with some accuracy and he was able to measure weight.

These two elements alone are in fact the basis of all commonly used acoustics in violin making. I find it hard to believe that the old Cremonese makers would not have relied on their judgement and observation of these elements over time to help ensure the quality of their instruments. Interestingly, Stradivari was probably not able to measure thickness exactly, something modern makers take for granted, a thicknessing caliper accurate to 1/10th of a millimetre being standard equipment on every modern violin makers workbench.

So, why not leave it at just that? Now we are measuring things and using concepts way beyond the 17th and 18th centuries. Why all the extra paraphernalia? Well, we could keep going with the careful, empirical methods violin makers have been using for centuries and have served us well, but to actually know why a certain change has a certain result is both forward leading and liberating. We can truly start to imagine the violin we want to make and be less a slave to the physical shapes we already know. For me, one of the most dramatic benefits has been better consistency from instrument to instrument. In fact, one of the great promises of violin acoustics is of improved consistency in making without the decades of trial and error.

Given the right equipment, it’s now possible to measure everything, from the speed that sound waves travel through the materials before making a violin as well as the density and the damping of these, to the potential output of a finished violin across its spectrum and the shapes of each individual mode of vibration. In addition, the way in which the bow moves the string, the way the bridge moves, the way mode shapes change from one to the next as well as many subtle side effects of relative mode position and amplitude have been exhaustively studied, and though much of this study is ongoing, the general effects are now well known.

So how can such an enormous amount of information be incorporated in violin making in a practical way? Obviously, it’s not possible or even

practical for a humble violin maker to utilise all of this, not least because of cost and time constraints, but a lot of it is easily accessible via a smartphone and a few other bits and pieces. Unfortunately to be effective, it still requires consistent note taking, something that doesn’t always come naturally to the craftsperson type!

Here are some examples from my own workshop practice, with a disclaimer: none of these procedures are my own invention. I’m indebted to numerous acousticians and violin makers over the last half century who have worked on both theory and practice and continue to do so.

To begin with, I measure the speed that sound waves travel along the grain of the rough pieces of wood for the top and back. This is easy to measure quite accurately with a smartphone, a hammer and a simple formula. I also measure the specific density. Again, easy to do by weighing it and dividing by the calculated volume. The two resulting figures for speed of sound and density give me an overview of the responsiveness I can expect from the plates as well as giving me some guidance for arching height and shape. Some measurements I have enough experience with for them to provide direct guidance. I do also measure the speed of sound across the grain, but this is observational only for me at this point.

A concept borrowed from other branches of structural acoustics is the notion of impedance. This

involves combining, via a formula, the mass and the calculated stiffness of an object to estimate how much energy is required to cause it to move, or flex. Stiffness in the case of violin plates is calculated from tap tone frequencies, taken on an app on a smartphone. As I work on the thicknessing of the plates, I regularly recalculate impedance, treating the number the formula gives me as a reference number to guide progress. Over the years I have become very sceptical of our (including my own) ability to feel when a plate has the “right” amount of flexibility, maybe as a result of too many conflicting views while attending violin making group workshops! I still flex plates as much as anyone, but as much as my scepticism about the accuracy of feel has increased, my confidence in the impedance calculation has grown.

Two violin bridges cut to exactly the same dimensions can sound very different to each other because of the variability of the material, even with a material as carefully selected and controlled as bridge wood. This unwanted effect can be minimised by bridge tuning. The side-to-side rocking/flexing frequency of the bridge, along with the weight, are two of the most important measurements for this. Most violins will sound better with a rocking frequency above about 3000 hz, measured by

Abandon all that hard metal for some lovely soft guts under the fingers. Great strings from Aquila, Kurschner, La Folia, and Toro are available now. Plus rosins, baroque and transitional bows and some wonderful string and ensemble music.

Contact patrice on (07) 3129 0537 or patrice@saraband com.au

clamping the feet in a small vice, flicking one bridge arm with a fingernail and measuring frequency at the other side with, you guessed it, a smartphone. In my workshop, I aim for a much higher frequency than this, as much as 3400 hz if the bridge blank will allow it, and mostly this sounds round and balanced just as it is. Occasionally, a violin will feel a little glassy under the bow and I have had success solving this by narrowing the waist and thus lowering the frequency by up to about 150 hz. It seems some violins benefit from having a bridge tuned to match in some way.

Recently I have been working on a special rig to measure sound radiation, not only for violins and violas but also for cellos, which have been much less studied in this way. On this rig, the instrument is held in a way that is firm but allows the body to vibrate and the strings are damped. The side of the bridge is tapped with regulated force by a small hammer. The sound output is picked up by a specially designed, flat spectrum microphone and fed into a computer where it is transformed into a graph showing the instruments output spectrum from that tap. On this graph we can see all the peaks, troughs and their relative amplitudes that the instrument produces from an even, “white noise” input. This is still work in progress, there are still many details to iron out particularly in the specifics of microphone placement and the regulated tap. All the same, seeing what I think I am hearing quantified on the screen has been profound for me and I’m looking forward to seeing what avenues this opens up.

I think it’s worth reminding ourselves that musical instruments are physical objects and are subject to the laws of physics. Understanding the interwoven causes and effects in a complex structure like the violin is not easy, but a lot of work has already been done and with smartphones and computers, it’s more accessible than ever. The violin, though it’s about as deeply woven into our culture as it’s possible for an object to be, can never really stand on its own, rather as a tool, an intrinsic part of the greater artwork that is music. Let’s work to make the best tools we can. Whether or not Strad needed acoustics is irrelevant in my view. I hope many makers will join me in using acoustics to improve our work and our knowledge about the violin.