4 minute read

Have a Chuckle, it Might Make You a Better Jew

Gary Hofman

Advertisement

Jerry Seinfeld

As a people, we are quite funny. I could list off Jewish comedians, but it seems like a useless task to me. I am sure that more than one has already come to mind. It also seems useless for me to tell you that the act of laughter is one of the most satisfying sensations that one can feel. Let’s be completely honest, having a good side-splitting laugh is not only an electrifying feeling, but it is also one of the greatest mental cures. If you are having a bad day or even a mediocre one, a good joke can turn that around into one to be remembered for all the right reasons.

There is plenty of academic writing of why laughter and humour are so good. One of the earliest modern pieces on joking was written by everyone’s least favourite psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud. If you want to look at it from Freud’s perspective (in most circumstances I would not want to, but trust me, here it makes sense) it is because jokes are linked to our unconscious and allow us to expel what we have been repressing. This makes sense, humour is an easy way tap into taboo subjects and bring them to the forefront of conversation.

Further, humour possesses power. Persecution is not an unfamiliar circumstance for Jews and neither is their response of joking about such circumstances. Robin Knepp accounts that during the atrocities of the Holocaust “there was laughter – joyful, liberated laughter from those who suffered the most”. Knepp argues that comedy was used to combat the misfortune of the Jewish experience during the holocaust and, ultimately, comedy was a tool to inspire hope, spirit and survival.

So surely, with all these potential powers, making someone laugh is a mitzvah. Right? Perhaps not. When looking around for a religious text on laughter and humour, I came across a quote from Pirkei Avot:

“One should not be a person of levity and mockery (‘s’chok v’hatail’), nor sad and somber, but cheeful (‘samai’ach’). So too did the Sages say, ‘Mockery and lightheadedness accustom [a person] to lewdness’ They likewise commanded that a person not be unrestrained in levity (‘parutz (broken out) bi’s’chok’) nor sad and mournful. Rather he should receive all people with a cheerful countenance.”

This stumps me. Mockery is understandable, Levity, however, I struggle with. Levity, the treatment of a serious matter with humour. Levity is something that Jews are all too familiar with. Going as far back to the exodus from Egypt, when faced with the pursuing Egyptians on one side and an enormous body of water on the other, Bnei Yisrael called to Moshe: “Are there not enough burial plots in Mitzrayim that you took us to the desert to die?”

This line here is a moment of dramatic irony, filled with comedy. There is no doubt that this is not a serious question. It is characteristic of the type of humour that we relate Jewish humour to now but more importantly, it is using a terrible situation as a source of comedy. Even in our earliest moments we were filled with levity.

Fast-forward to World War Two. As the war rages on, the Jews in Europe find themselves in concentration and death camps. Although the humour narrative might not be one that we hear about often, there was one that surfaced in the camps. Charlotte Delbo, a French author, recounts how her and her fellow prisoners created a production of The Imaginary Invalid, a Molière satire about the medical profession in the seventeenth century. She explains that it helped them escape from the situation they had found themselves in. Hani Merich explains how comedy can act as “a shield and as a tool for rising above an incomprehensible, horrific experience”.

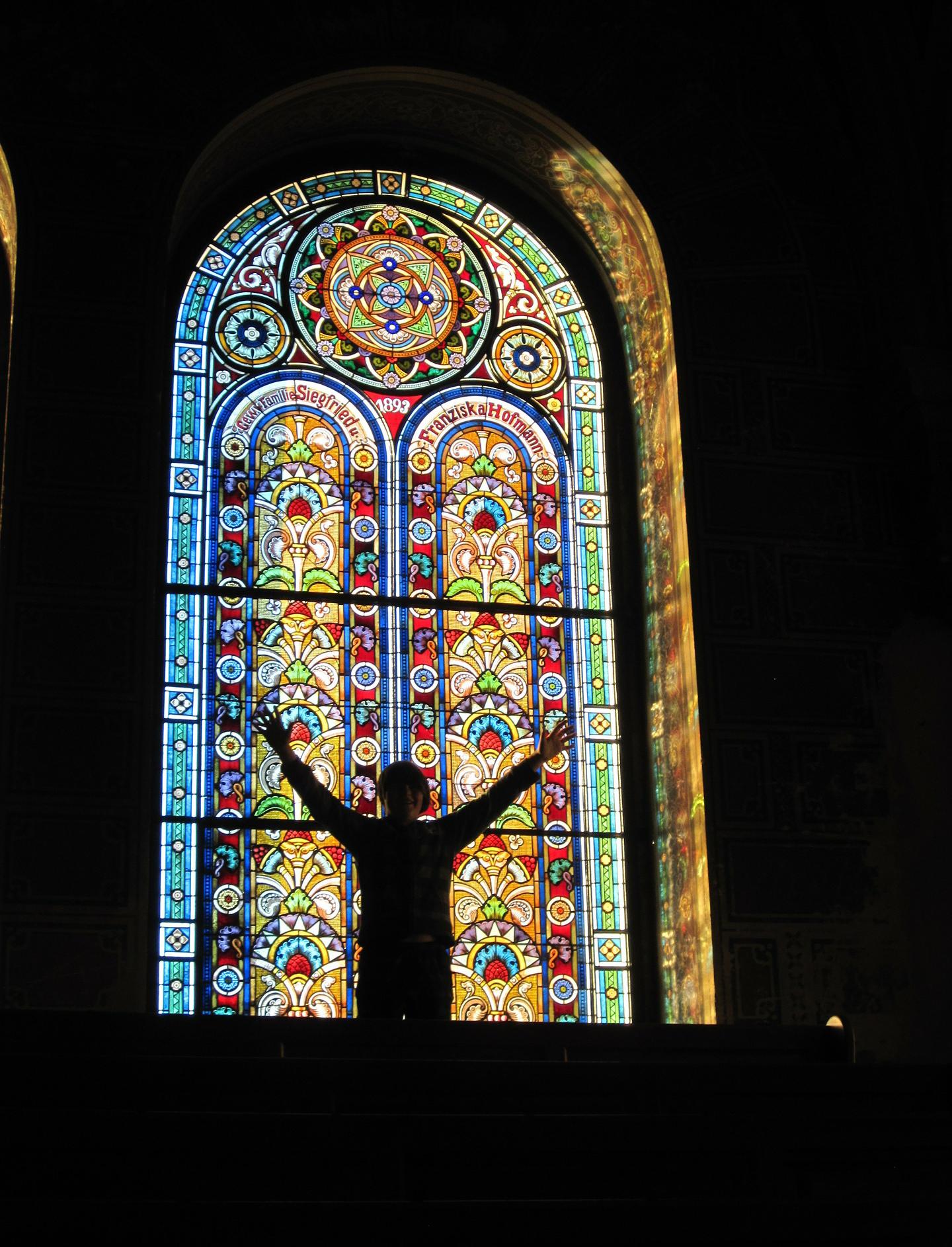

Removing ourselves from experiences of impending death, we even find humour in our places of worship. Surely, this would be the most inappropriate place to crack a joke. It is a common occurrence in my Shul for the Rabbi to start his weekly speech with a joke – although the humour is often lost on me, this reflects what is written in the Talmud. The Talmud writes that “before the great sage Rabba began his lecture, he would crack a joke, the rabbis would laugh, and then he would sit down with awe and reverence and begin his lecture”. Is this not levity?

This brings me to my point. I am no expert. I have laid out some facts but alas, I do not have the answers to the questions I am asking. I think it is obvious though that perhaps humour and laughter is not lost on us. It has been a escape, a medicine and a point of discussion. Of course, if someone like the Rabba would indulge in a bit of levity now and then, why shouldn’t we? The end of the line that says we should not act with levity also says that we should meet people with a “cheerful countenance”. If humour is not a cheerful countenance, then I do not know what is.