9 minute read

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 3 The Activities Carry the Farm

Hop

Advertisement

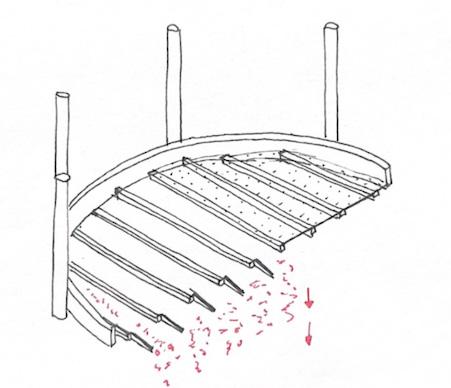

September. The first hop cones are ripe, ready to be harvested. The village gathers on the farm as the sun rises. Men, women, children; no one is left behind. A basket for each, and a chair, ready to head to the field. The cones are handpicked one by one, the baskets slowly fill up. Singing, gossiping, laughing; the day goes by, until the first basket is full. The basket is brought to the kiln. A dark, warm, narrow space. It is carried up the stairs, until an opening is found to enter the central kiln. The basket is turned over, emptied onto the perforated floor. The cones are spread out equally, set to be dried. The basket goes back down, ready to be filled with new cones, again. The cones are dried, the perforated floor is tilted. The hops fall down, into a sack. Time to cool down.

After weeks of picking, the last cones have been harvested. The last batch is dried. The sacks are set for the brewery. The village cheers: time for a feast. Games, dancing, singing, until the sun rises. The baskets, the chairs, the village, disappear. The field is left to rest.

Hopped Apple Cider

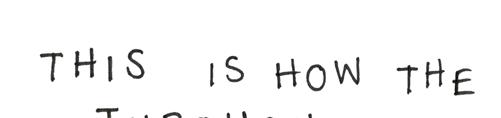

Together with the neighbouring farmer, we produce hopped apple cider, an unicum in Belgium. The making of the apple cider takes place in the neighbouring farmer’s glasshouse. The community takes on the three last steps of the cider making process: the fermentation in wooden barrels, botteling the cider and the riping of the cider in the bottles. There is no fixed furniture in the glasshouse, the area is built up every year when the time for the production starts, and broken back down at the end of the process. A table is also set up for meetings with the farmer.

The two ingredients are brought together in the glass house on the neighbouring site. A transparent space, with a fragile border existing of a wooden door above a ditch. The community takes on the three last steps of the cider making process: the fermentation in wooden barrels, botteling the cider and the riping of the cider in the bottles. There is no fixed furniture in the glasshouse, the area is built up every year when the time for the production starts, and broken back down at the end of the process. Between the barrels and boxes a table is also set up for meetings with the farmer and community.

The second main activity is bricolage, although we don’t expect certain skills. We got this idea after making a photocollage of bricolage in the Flemish countryside. Although by many perceived as poorly made non-architecture, for us it has certain qualities that really fit our community and our vision. Beside the many qualities, we need bricolage in our farm. Because our parcel is not extremely big. The facilities need to be adaptable, depending on the season. By bricolating, we can give buildings multiple functions. It gives a flexibility, which is a strong facet, especially in the current reality of climate change.

Bricolage3

Bricolage is a French word, first introduced by the French anthropologist Lévi Strauss in 1969. It is derived from the French verb “bricoler”, which translated means ‘to tinker’. However, bricolage is more than just tinkering: it is a way of using all that is available to quickly fix a problem or to adapt what exists when new circumstances arise. Bricolage doesn’t depart from a technique or skill, but relies mostly on the creativity of the individual who is performing it, the bricoleur. The bricoleur is more an artist than a craftsman. No particular skills are needed, no aesthetic end result is expected. This takes the pressure of failure away and improves the creative process.

Or as Colin Rowe describes in his book “Collage City”:

‘The bricoleur is adept at performing a large number of diverse tasks. His universe of instruments is closed and the rules of his game are always to make do with ‘whatever is at hand’, that is to say with a set of tools and materials which is always finite and is also heterogeneous because what it contains bears no relation to the current project, or indeed to any particular project, but is the contingent result of all occasions there have been to renew or enrich the stock or to maintain it with the remains of the previous constructions or destructions.’ * (Rowe, 1984, p. 102-103).

When bringing a diversity of materials that have no relation to the current project together, it results most of the time in a patchwork-like non-architecture. This randomness and mishmash are praised by some. And as a result, some architectural offices today use ‘bricolage’ as a design methodology to achieve a certain aesthetic. However, it is important to be critical in these cases, because if we use bricolage as an aesthetic method, it is limited to an architectural style. And this is not what bricolage is about.

*Rowe, C. (1984). Collage City. Mit Press Ltd. CHAPTER 3 - The Activities Carry the Farm

Mushrooms

The growing and harvesting of hop only takes half a year, therefore in order to financially survive the community needs to produce other foods. In our case, these foods are mushrooms. What makes mushrooms really interesting, is not the just the practicality behind it, like the simple infrastructure and circumstances it needs to grow, but also the philosophy of a mushroom. They have a certain flexibility, and randomness in where they grow. They are little satellites that can grow almost everywhere on the farm. They use waste or death material as growing base, giving it a purpose again. Mushrooms are in this way a bit of bricoleurs.

“WHAT DO you DO WHEN YOUR WORLD STARTS TO FALL apart? I go for a walk, and if I’m really lucky, I find mushrooms. Mushrooms pull me back into my senses, not just—like flowers—through their riotous colours and smells but because they popup unexpectedly, reminding me of the good fortune of just happening to be there. Then I know that there are still pleasures amidst the terrors of indeterminacy.”

“Like rats, raccoons, and cockroaches, they are willing to put up with some of the environmental messes humans have made.”

QUOTE from “The Mushroom at the End of the World” - Anna Tsing

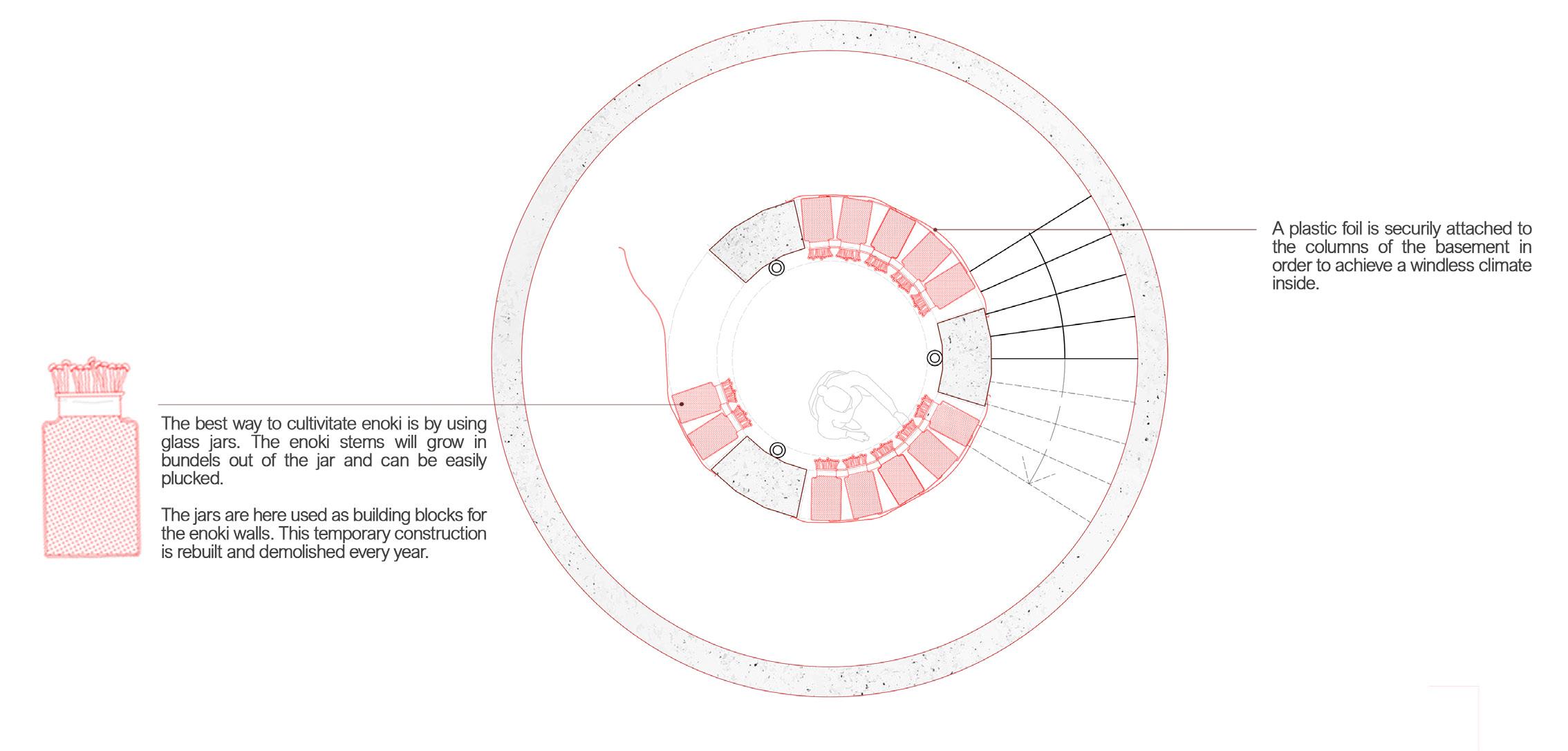

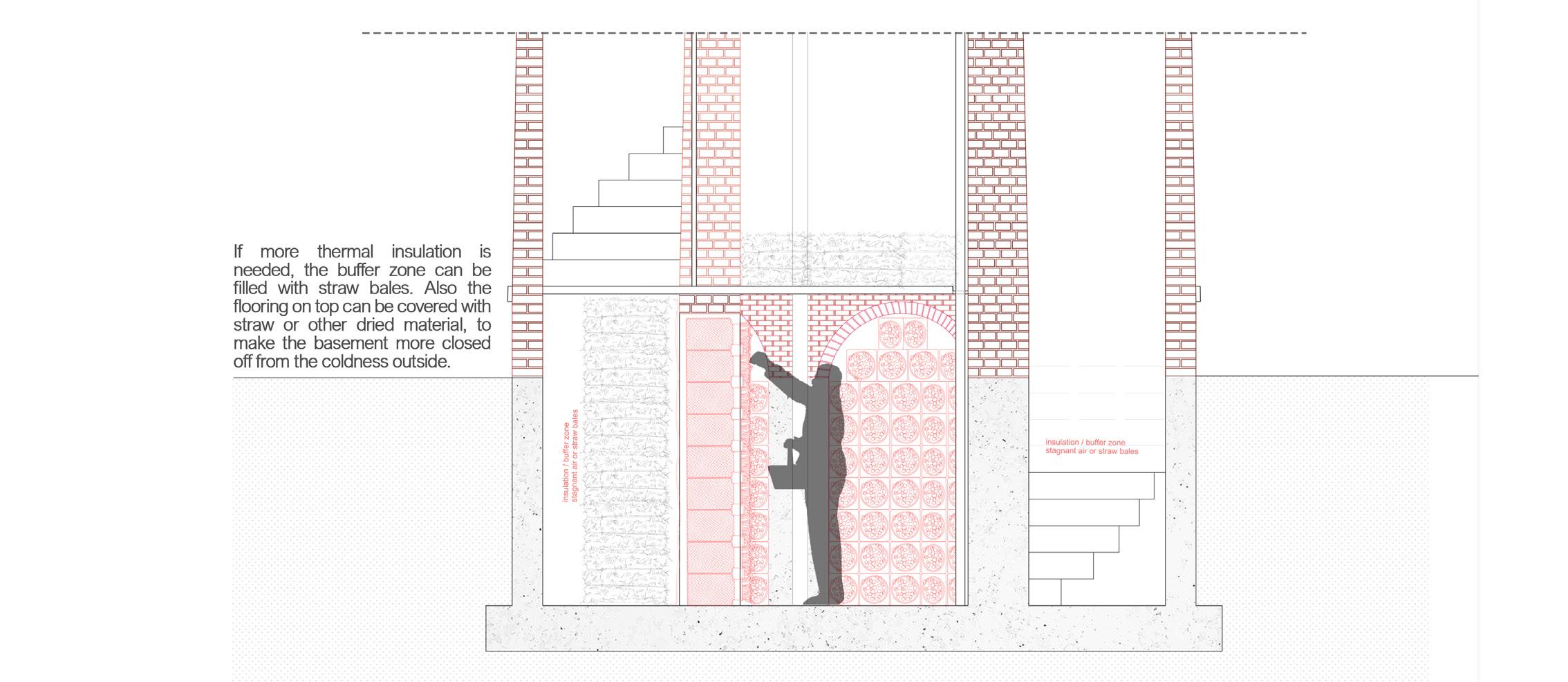

Enoki Mushrooms

enoki basement in the dry tower

Ten months of the year the dry tower isn’t used as a drying tower.

What happens when buildings are not used? Nature takes over. This was the starting point for this mushroom intervention.

An empty basement, with a core, surrounded by a buffer zone, lends itself as the ideal habitat for enoki mushrooms. Enoki mushrooms, also called velvet foot, is the most fragile type of the farm. It needs more warmth, than the others.

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

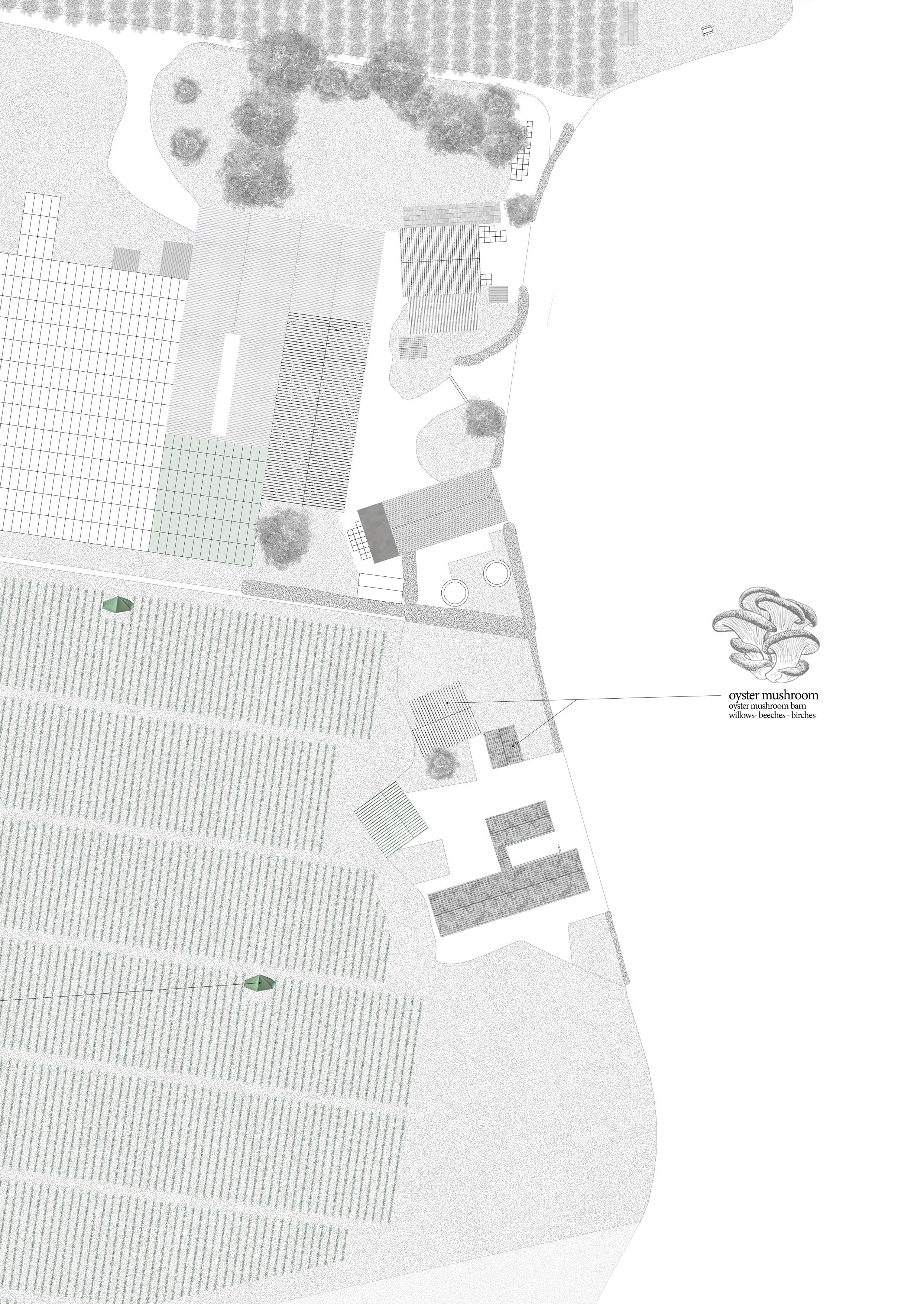

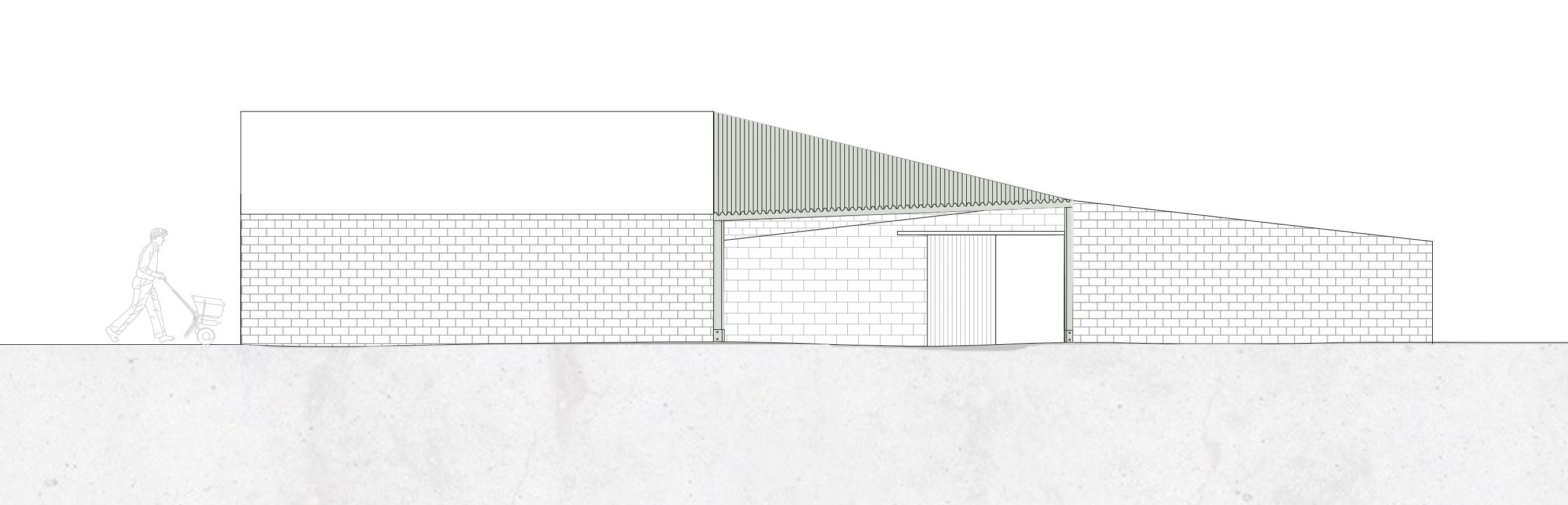

Oyster Mushrooms

in the mushroom grotto

Interestingly these mushrooms thrive on death plant material and are not that high maintenance. Although supermarket ask high prices for them.

Old coffee grounds, collected from different coffee bars and restaurants in Antwerp, are the main compenent of the breeding grounds. The mushroom bags are prepared in the mushroom atelier and then brought into the grotto. Before entering, you need to put on a mask en white gloves and shoe protectors.

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

69

Shiitake Mushrooms

on straw bags and tree trunks hidden in the hop fields

Shiitake are one of the most wanted mushrooms in the kitchen. Even though they are more expensive than the white champignon, they are way more easy to cultivate.

Shiitake, the cleaning mushroom, thrives on death organic material: tree trunks and straw bags as an example. Plus, they are not high maintenance. Only a spot out of the wind and direct sunlight is needed. And if you want a higher production a shiitake bath can also be useful. Letting the trunk bath for 1 day every 6 to 8 week results in a more efficient cultivation.

Spring and summertime: the hoods are hidden between the hop fields. Only the inhabitants know where they are.

Autumn and winter: the hop has been harvested. The hoods pop up and become visible to passers-by. Like a mushroom, out of nowhere and on random places.

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

73