7 minute read

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 2 Welcome to the Community

Advertisement

I drive my bike into the yard and park it under the old tree next to our communal space. As expected everyone is busy. It’s the end of September, peak season in our community. During the last week, the whole community has been involved in the harvesting of the hop. The next days will be challenging: everyone is tired and when working that close, sometimes frustrations grow.

Five years ago we decided to ask for extra help during harvesting season. Normally we are a community of 13 people, most of them are families that immigrated some years ago. Now, we have 4 new temporal inhabitants.

Living together with 13 and sometimes 17 people means we also need social boundaries, rules and structure. These are not fixed and can change if they no longer benefit our community. I think that’s exactly what rules should be. They are beliefs you have in common, but shouldn’t dictate those who live there. Because then they limit the individual freedom.

Inclusion5

The word inclusion means the act of including someone or something as part of a group, list, etc. and thereby excepting his/her differences. Or differently said: the act or practice of including and accommodating people who have historically been excluded. Since it concerns social groups, we can call this ‘social inclusion’. In our current democratic era inclusion is seen as a universal human right, yet it’s not always acted upon. All people, irrespective of

Age – Gender - Sexual orientation – Education – Income – Religion - Cultural beliefs – Ethnicity – Language - Mental health

should be heard and should be given equal rights and opportunities.

architects inhabitants

activities

hop + hopped apple cider

enoki mushrooms

oyster mushrooms

shiitake mushrooms

bricolage

neighbouring farmer tourists / passers-by / the outside world

House Rules

1. Horizontal Governance*

A general assembly is held every two weeks to discuss ongoing issues and take decisions. In case of conflicts too, dialogue is the main governance approach. A third party from another community can be involved, he/she can mediates the dialogue and bring back experience in his/her own one.

2. Tasks Organisation

Taking care of the place should be done collectively (in pairs at least and in a rotational manner).

3. Interaction & Communication

with the commune farms and non-community members (local farmers, outsiders, schools, artist, friends):

Every month someone is responsible of the outside communication and he is in charge of the relations with outsiders (this person can be the third party mentioned above).

4. Support Network

Each community member can engage in the Support Network. Its aim is to support alternatives to distance from industrial farming and develop awareness regarding waste, technology use and associated emissions. Among its actions, this ‘committee’ organize a seasonal event (held in a commune farm) adressed to members, outsiders and the neighbour villages.

*On the first Saturday of each month at the meeting, a new family is designated to be the representatives of the community. Appointing a whole family instead of one individual avoids having a sense of hierarchy. This family takes on a leading role for the month, makes sure the work runs smoothly to meet the needs of the community.

Participation of each inhabitant is required. Daily tasks are divided amongst the inhabitants but are not binding. An activity must not define an individual. But, negotiating is possible.

The Belgian Immigration Climate: What Are the Shortcomings?

To understand the importance of building a community for immigrant families, it can be useful to get a general overview of the Belgian policy of immigration. As most institutional structures in Belgium the immigrant policy is also victim of the complicated federalism. The first stage of immigration, the asylum and reception placement, is defined at the federal level, the following step of integration and housing is regulated at regional level. This difference in administration results in not one institution taking full responsibility. What happens is this: there is no support for recognized refugees when they leave the asylum and are thrown into the housing market.

The integration paradox in Belgium:

“During their stay in these asylum centres, refugees are not supposed to integrate into society; and yet, immediately after their formal recognition, politicians expect refugees to integrate as quickly as possible.” (De Decker, P. et al, 2020, p. 86)

Immigrants experience many difficulties when searching for a house. Most refugees have not built a social network to rely on, moreover the governmental support is almost non-existent. Therefore they are completely independent in the search for a home. The biggest obstacle is the language barrier between immigrant and landlord. The article uses the term ‘taste-based discrimination’. Landlords will more likely rent to families who communicate in the same language and have a guarantee of adequate income. In many cases, the refugee families do find a home, part of specific city neighbourhoods. As those areas are mostly segregated, they can become stigmatized by outsiders. The danger lays here in stigmatizing those who live there too, making it almost impossible for them to fully participate in society.*

The trajectory from reception/asylum to housing in Belgium (adapted from article). *Wyckaert, E,. Leinfelder, H. and De Decker,P. (2020). Stuck in the Middle: the Transition from Shelter to Housing for Refugees in Belgium. Transactions of the association of European Schools of Planning, no. 4: 80-94.

How do we position our community in this reality?

The influence of adequate housing is crucial in the process of social inclusion. As shown in the scheme the transit period, where refugees have time to search for a house, is between 2 to 4 months. Finding a house on the regular housing market is impossible, plus the government doesn’t provide social housing. With our community, we offer an alternative by not only providing a house, but also making them part of an existing community and farming company. We are aware that this will cause conflicts. Evidently the lack in communication and the general stereotyping that happens. It’s also unusual to have a refugee community in a privileged area, that is populated by middle-class natives.

Can we use principles from restorative justice to facilitate a convivial community?

In restorative justice a different approach is applied to conflict; most importantly centralizing communication between all individuals. In the current immigration policy many conflicts occur. Since the lack of verbal communication is one of the main reasons why inclusion becomes so complicated, we were interested if there were other approaches of restorative justice we could put to use in the community. Trust plays an important role in building a convivial community, including the trust in conflict and failure. This is also a characteristic of conviviality: there is no naïve belief in having a perfect community. More important is to acknowledge that challenges and uncertainties will happen.

To achieve trust within the community and between us and outsiders, we have to adjust our obsessive attitude towards security that gives most of us a feeling of false safety. Rigid boundaries distance ourselves from the other and feed segregation, prejudices and fear even more. A certain transparency and sometimes confrontation is needed. This can be done through active participation, preferably individual in a local environment.** In restorative justice the focus lays on the individual, rather than the institution. Ivan Illich advocates for the same individual freedom in his book “Tools for conviviality”:

“A convivial society would be the result of social arrangements that guarantee for each member the most ample and free access to the tools of the community and limit this freedom only in favour of another member’s equal freedom.” (Illich, 1973)*** Being more transparent, opening up communication, promoting cooperation, calling for dialogue and not being avoidant of conflict can make a community a convivial project. These tools go further than just verbal communication. Instead, rather than focussing on creating the same language, convivial communities recognize differences in norms, values, feelings, languages etc. and focus more on restoring when challenges or conflicts occur.**

**Pali, B. (2019). Restorative Justice and Conviviality in Intercultural Contexts. Verifiche, Rivista Semestrale Di Scienze Umane, no. 2: 155-178.

***Illich, I. (1973). Tools for conviviality. London: Harper & Row.

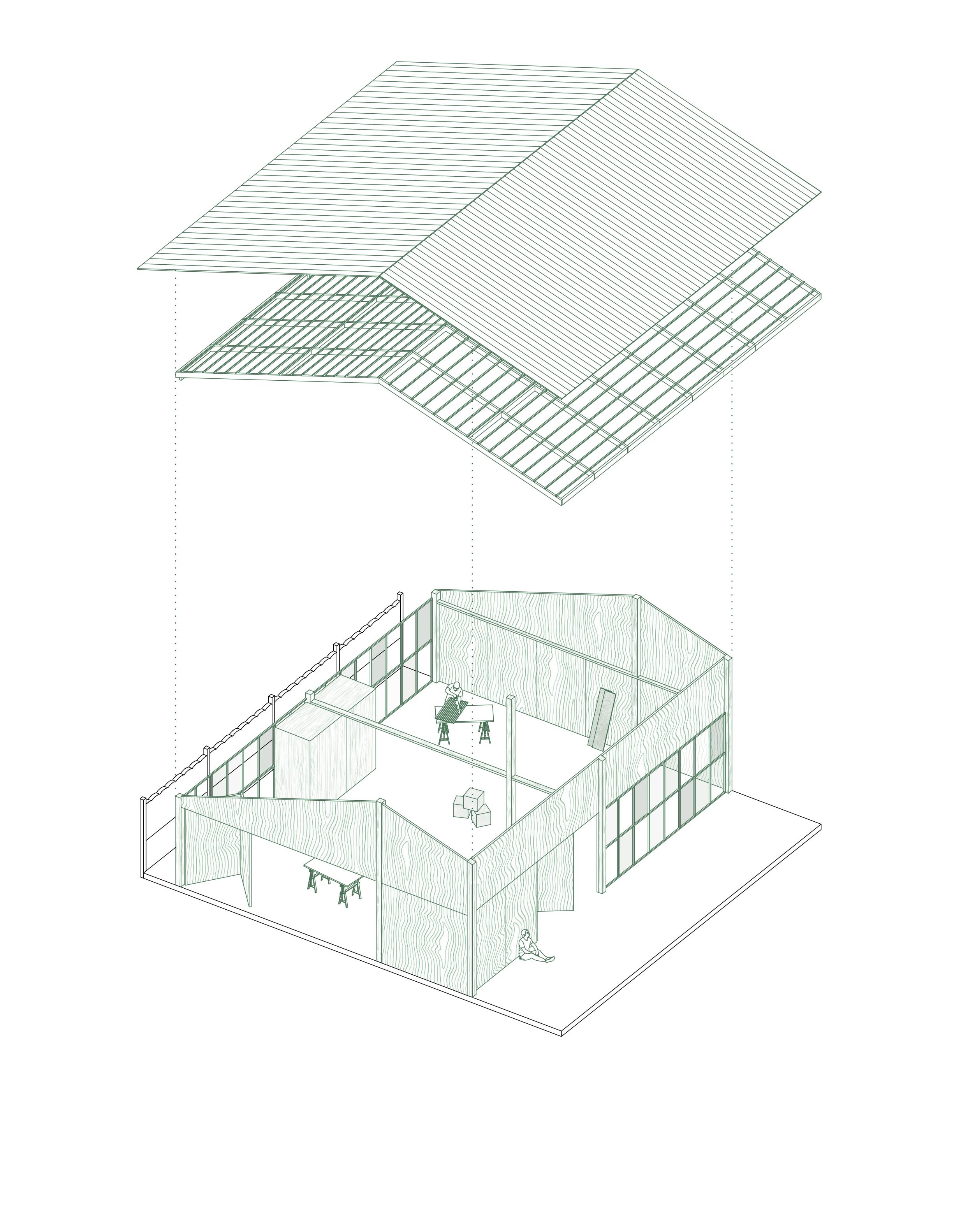

I enter the communal space with the hope of finding someone here. Unfortunately it’s completely empty. Everyone has gathered in the fields. Not that I can see them, they are hidden between the meters of hop bines. Next week when all the hop is picked, we host the harvesting feast in this same space. It always strikes me how many people can fit in this one open space. When we meet each Saterday around the table, everything seems way smaller and more intimate. We close off the doors and only reopen them when all problems are solved.

daily

weekly

monthly

yearly

43