Indian Paintings Royal Portraits ART PASSAGES

Maharashtra, Aurangabad, circa 1740

Ink, opaque watercolor, washes, and gold on paper

Painting 9 ¹⁄₈ x 8 in (23.2 x 20.3 cm)

Two noblemen sit with their legs under them against striped bolsters on a patterned carpet. Clearly, they are outside on a terrace with a black railing. The figure on the left holds a white flower in his left hand and the mouthpiece of a huqqa in his right. He faces the other man who has one hand on his lap and holds prayer beads in the other. It is clearly a formal scene. Assorted items are placed on the carpet including a katar or punch dagger, a zafar takieh or cushion of victory, a fan, and a bidri huqqa is in the bottom left corner. A small pet cat is perched on the bolster to the left and a small table with a written piece of paper is between the two pillows. At a distance, a mango tree full of fruit hovers against a dark olive-green background, with the hint of the sky at the very top. It is populated by squirrels, monkeys, and parrots. An egret flies to each side.

The main figure to the left, possibly a foreigner, is wearing a North African garment, a type of kaftan called a farasia or farajiya that is a thin diaphanous garment worn over other clothes. The Deccan was quite cosmopolitan and individuals from various parts of Africa often rose to important positions.

This painting has affinities to a painting in the Mittal collection of a man called Nawab Muhtaram Khan Bahadur Muhtasham Jang. It is attributed to an artist named Muttam who used to be referred to as the Jaipur artist. The way the carpet is seen from above with its borders along the edges of the painting and the egrets in the sky are similar. The palette here is less varied and subdued.

John Seyller and Jagdish Mittal, Deccani Paintings, Drawings and Manuscripts in the Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art , Hyderabad: Jagdish and Kamla Mittal Museum of Indian Art, vol. I, no. 45.

India, Mughal, circa 1680-1700

Ink drawing with colored washes

Folio 9 ¾ x 7 ¹⁄₈ in (24.7 x 18 cm)

Painting 8 ³⁄₈ x 5 ¾ in (21.2 x 14.6 cm)

Provenance

Private collection, Paris 1975-2000

In this superb and detailed drawing of a man in midlife, one gets an impression of the sitter’s determination and intensity as he gazes straight ahead. His pagri or turban is delicately detailed with floral scrolls separated by bands of lavender stripes. He sits with one leg tucked under him and the other one with a knee bent against a bolster upon a carpet with a border of delicately drawn floral scrolls containing a field of similarly drawn floral sprigs. A small lota and a white cloth lie nearby. He holds the mouthpiece of the huqqa with his left hand and rests his right on his lap.

The artist gives just a hint of the details of the blue and white ceramic base for the huqqa and handles the folds of the man’s diaphanous jama or garment deftly. A light wash of white over the carpet and bolster delineates the space from the background. Horizontal strokes of color give a dreamy quality to the sky letting us know that he is positioned on an outdoor terrace.

This type of drawing with a few hints of color is called Siyah Qalam and is a technique often used for portraits during the Mughal period.

Ink, opaque watercolor, washes, and gold on paper

Painting 16 ⁷⁄₈ x 10 ¾ in (42.8 x 27.3 cm)

Provenance

Indian Paintings from the 17th to 19th centuries, Waddington and Tooth Galleries, London, May-June 1977, no.4

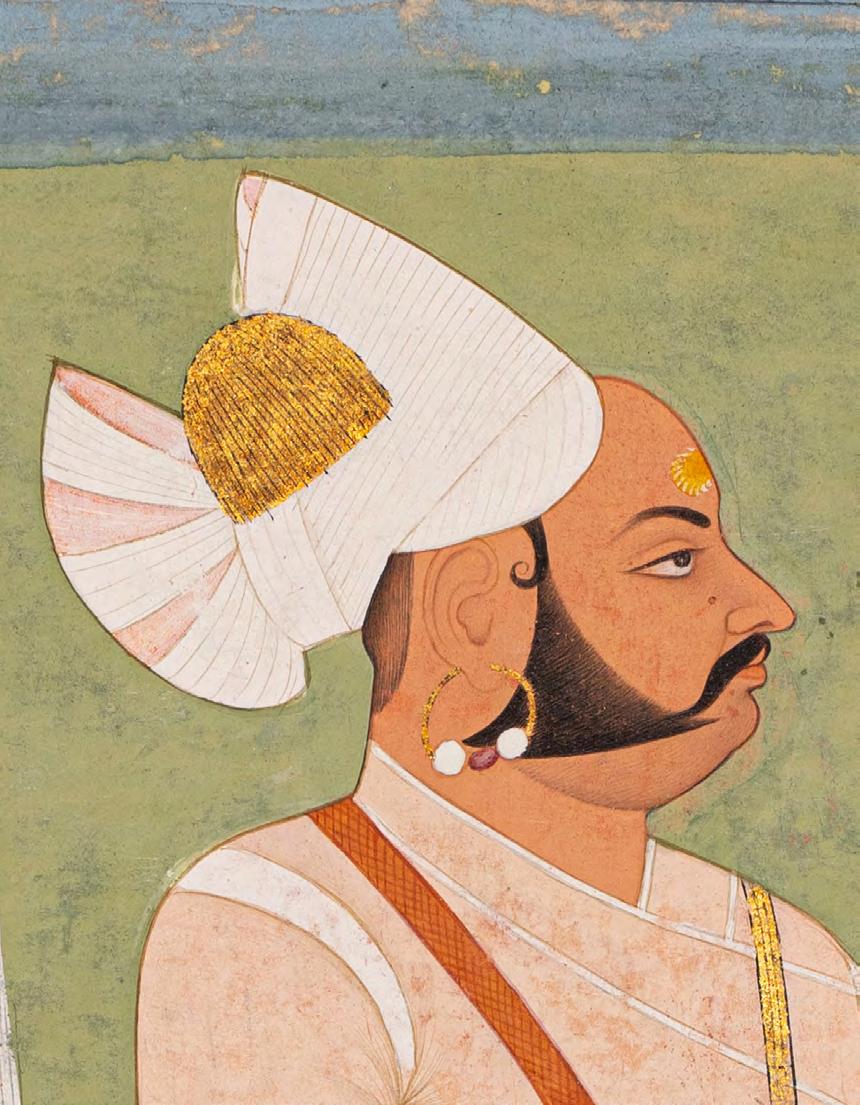

Inscribed on the back in Nasta‘liq: Abu Sa‘id and in Dutch: Aboe Seeth and in Devanagari: AbhuSed pata?jah

Towards the end of the 17th century artists at Golconda, the capital of the Qutb Shahi dynasty, created many albums or muraqqa‘s depicting both Mughal and Deccani rulers and dignitaries for Europeans visiting the city. Pauline Lunsingh Scheurleer in the reference cited below listed seventeen albums. Unbound examples in many public and private collections are likely from such muraqqa‘s

This portrait and that of Aurangzeb in the next painting are from a luxury album of large portraits that was labeled Mongolsche Keysers which was possibly acquired by the Dutchman Cornelis de Bruijn (Cornelius de Bruyn and Corneille Le Brun) in 1700.

The painting here represents Sultan Abu Sa‘id Mirza who was the great-grandson of Timur, founder of the Timurid Empire. He was the greatgrandfather of Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire of India. He appears in engravings that were copied from two albums published by Chatelain and Valentijn in the early 18th century. In Chatelain, the figure with the bow and arrow is labeled as Mirza Seyed and in Valentijn as Mohamed ou Miramont. In both cases he is seated, which is consistent with four paintings of him in two albums in Dresden, noted below, which are labeled with different names from the genealogy.

A properly labeled group of the Timurid and Mughal genealogy portraits comprised of oval Telangana, Golconda, circa 1695-1700

head shots has Sultan Abu Sa‘id Mirza’s father Sultan Muhammad (C111/3) holding an arrow so there seems to have been some confusion.

Following a typical Mughal format, Sultan Abu Sa’id Mirza stands on a thin groundline against a solid blue background. The ground is strewn with flowering bushes. He wears a Persian style pagri and sumptuous sherwani or overcoat, trimmed with fur around his neck.

For the Dresden paintings see: Petra Kuhlmann-Hodick, ed., Indian Paintings the Collection of the Dresden Kupferstich-Kabinett , Dresden: Sandstein Verlag, 2018.

CA 113/161 inscribed Miran Saida , CA 111/18 (fol. 14) inscribed in devanagari: Miran Shah, CA 111/54 (fol. 50) not inscribed, and CA 111/60 (fol. 56) inscribed in nasta’liq and devanagari Abu Sa’id and also on the reverse in devanagari with the number 4.

Henri Abraham Châtelain, Atlas Historique…, Amsterdam: Chez l’Honoré & Châtelain, vol 5, 1719, p. 176. Mirza Seyed Derde groote Mogol Francois Valentijn, Oud en Nieuw Oost Indien…, Dordrecht: Joannes van Braam and Amsterdam: Gerard Onder de Linden, vol. V, plate no. 36, 1724–1726.

Pauline Lunsingh Scheurleer, “Het Witsenalbum: zeventiende-eeuwse Indiase portretten op bestelling,” Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum 44 , 1996, no.3, pp. 167254 with an English summary: “The Witsen Album: 17th-century Indian portraits to order,” pp. 266-270. The museum also has this album on-line. Her list does not include quite a few other albums, some which include numerous portraits. The most accessible sets are in the British Museum which concentrate on the Mughal lineage with a few later Qutb Shahi kings (acc. nos.: 1974,0617,0.2 .1-67 and 1974,0617,0.4.1-51).

An on-line article on these albums can be found at: http://www.journal18.org/issue6/efgies-in-transit-deccanportraits-in-europe-at-the-turn-of-the-18th-century/

Mirza

Telangana, Golconda, circa 1695-1700

Ink, opaque watercolor, washes, and gold on paper

Painting 16 ¾ x 10 ¾ in (42.5 x 27.3 cm)

Provenance:

Indian Paintings from the 17th to 19th centuries, Waddington and Tooth Galleries, London, May-June 1977, no.5

Inscribed on the back in Nasta‘liq: Aurangzeb and in Dutch: Oranseeb ouwd 80 Jaaren

Aurangzeb (the emperor ‘Alamgir, 1618-1707) wears a simple white jama and pagri. He holds a sword in his left hand and a dagger is tucked in his decorated patka or sash. As is common in paintings of Aurangzeb he holds an open book in his right hand. It is unclear when or why the Dutch inscription claims that this is a painting of Aurangzeb at the age of 80, since portraits of him in old age usually have his head bent forward and his shoulders hunched over. A painting dated 1110 AH/1698-99 in the Victoria and Albert Museum (IM.234-1921) depicts ‘Alamgir with hunched shoulders. The album from which this painting comes from also contains a portrait of Aurangzeb as a much younger man and purports to be him at the age of sixty.

Single portraits from the present album have sold in Sotheby’s, London, 12 October 1981, lot 34; 15 October 1997, lots 72 and 73; 26 April 2017, lot 127 and 128; Sotheby’s, New York, 21 March 2002, lot 218 and Christie’s 24 April 1990, lots 85 and 86 and 27 October 2023, lots 6465 and 2 May 2003, lot 500.

Also see the Khalili Collection, MSS 1027-1028, Shah ’Alam and Babur.

Mughal, circa 1680s

Ink, opaque watercolor, washes, and gold on paper

Painting 8 ⁷⁄₈ x 6 in (22.6 x 15.3 cm)

‘Azam Shah (1653-1707) was the third son of the Emperor Aurangzeb who briefly reigned from March until June following the death of his father in 1707. Azam was appointed as the heir-apparent (Shahi Ali Jah) to his father on 12 August 1681 and retained that position until Aurangzeb's death. Soon after ascending the throne following Aurangzeb’s death, ’Azam Shah was defeated and killed by his older half-brother Shah Alam, the later Bahadur Shah I, at the Battle of Jajau. Since this portrait has a nimbus, perhaps this painting is celebrating his becoming heir to the throne although other portraits of the royal princes sometimes do have halos.

The nimbate ’Azam Shah stands in strict profile. Richly dressed in a gold brocaded sherwani or overcoat, he has a dagger tucked in his patka or sash and his right hand is on the hilt of his sword, and he holds a jewel in his left hand. His feet are planted on a narrow strip of grass and the background consists of pale washes with billowing clouds at the top populated by birds.

The Boston Museum of Fine Art has a tracing of ’Azam Shah on skin (15.98) that is labeled in Devanagari as Ajam Shah Sajada which must stand for the Persian title for a prince Shahzada since Devanagari does not have the letter z. It is remarkably close to this painting in detail although his hands are in slightly different positions.

For a large portrait of Azam Shah from the aforementioned Deccani album, see An Eye Enchanted: Indian Paintings from the Collection of Toby Falk , Christie’s 27 Oct 2023, lot 64.

India, Mughal, circa 1660-70

Ink drawing with hints of color wash and gold

Folio 16 x 10 ³⁄₈ in (40.6 x 26.3 cm)

Painting 5 ⁷⁄₈ x 3 ½in (15 x 8.9 cm)

Inscribed lower bottom in Nast’aliq: Shabih Khan ‘Alam bin Najabat Khan (Likness of Khan ‘Alam son of Najabat Khan)

Inscribed in Devanagari: Sabir/ Khan Alam Ni [sic] jabat Khan robe?e

The placement of the painting within multicolored borders as well as the gold inscription in Devanagari at the bottom points to a Mewar royal muraqqa‘ or album of portraits of Mughal dignitaries. A Mewar inventory number on the verso further attests to its royal ownership. The strict standing pose in profile was extremely popular in Mughal and Mughal influenced centers. Placed against a plain background he wears a simple jama over richly brocaded tight trousers and shoes. His pagri or turban is banded in gold. A katar or punch dagger is tucked into his sash or patka and he rests both his hands on the helm of his sword. This type of drawing with a few hints of color is called Siyah Qalam and is often found in many formal portraits.

Ghairat Khan (Muhammad Ibrahim), the son of Najabat Khan, a distinguished courtier of Shah Jahan, was granted the title of Khan ‘Alam by Alamgir/Aurangzeb. This took place after Ghairat Khan commanded the Aurengzeb’s armies in battles against Maharaja Jaswant Singh and a battle with Dara Shikoh on April 25, 1658, during the Mughal War of Secession (1658 – 1659) between the four sons of Shah Jahan.

For biographical details see Samsam al-Dawla Shah Nawaz Khan and Abdul Hayy, The Maathir-ul-umara , trans, H. Beveridge, vol. 1, reprint Delhi 1999, pp 577 – 78.

His father Najābat Khān Mīrzā Shuja‘, an important courtier, is discussed in Vol. II, pp. 364 – 71.

For similarly treated portraits of other Mughal nobles from the same Mewar album, see “Portrait of Darab Khan at an Older Age” in B.N. Goswamy, Painted Visions: The Goenka Collection of Indian Paintings , New Delhi: Lalit Kala Akademi, 1999. No. 52, page 66 and for one depicting Abu’l-Hassan Asaf Khan formerly in the collection of Toby Falk, see Christie’s, 27 October 2023, Lot 5.

Madhya Pradesh, Orchha, circa 1740

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Painting 12 ¾ x 8 ¼ in (32.4 x 21 cm)

Inscribed in Devanagari: Śrī Mahārājā Pṛthī Sīṃha jī

The portly Maharaja Prithvi Singh (r. 1735-1752) stands on a marble terrace with his arms raised holding pink lotus flowers. He is worshipping a figure of Krishna as Venugopala, playing a flute, who stands on a low four-legged table with pink lotus covering. Krishna looks directly at the king. Balancing the composition, an attendant to the deity stands to the right side holding a morchal, a peacock-feathered flywhisk. The temple appears to consist of a shallow room with Krishna standing in the left bay. The building is topped by a small turret and flying flags of different colors. The courtyard appears small with a lone tree to the left and a narrow band of the parterres of a garden is along the bottom of the composition with a fountain at its center.

Prithvi Singh wears a diaphanous garment over his pink pajama and sports a bejeweled golden pagri or turban. He was known as a great patron of literature and music and was a poet known as Rasnidhi.

See: “Prithvi Singh watching a dance performance,” Asian Art Museum San Francisco 1991.245, circa 1750 and “Raja Prithvi Singh of Orchha being entertained” in B.N. Goswamy, Jeremiah Losty, and John Seyller, a secret garden Indian Paintings from the Porret Collection, Zurich: Museum Rietberg, 2014, no. 75, pp. 150-51.

Rajasthan, Udaipur, Mewar, circa 1830

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Folio 13 ½ x 10 in (34.2 x 25.4 cm)

Painting 12 x 8 ¼ in (30.5 x 21 cm)

Inscribed:

Māhārājadhīrāja Māhārāṇā Śrī Bhīm Sīngh jī Yāptā Kuvara Javāna Sīngh jī yīrājyāthakā://

The nimbate Maharana Jawan Singh (1800, r. 1828–1838) sits on a carpet against a bolster under a shamiana of red fabric decorated in gold and silver in front of a marble hall. He sits with a shield on his lap and has prayer beads in his left hand and the tube of an elaborate huqqa in the shape of a woman in his right hand. A noble sits facing him with his clasped hands raised holding his prayer beads and resting on a shield in front of him. Two attendants stand behind Jawan Singh, one holds a morchal or peacock flywhisk and the other holds a flower. Behind the noble, a courtier stands holding a flower and prayer beads in his hands. Another man stands on the marble terrace and holds prayer beads as well. All the men wear white jamas and pagris or turbans.

A hanging at the back of the tent depicts the radiating sun, a symbol of the Mewar house as head of the Solar Rajputs, is flanked on either side by worshipers. Below it a crescent moon hovers outside Jawan Singh’s nimbus. A processional or hunt scene is painted below the sun and parts of it are visible from behind the prince, his shield, and the bolster for the king. All the men wear jewelry with that of the Maharana and the noble elaborately displaying their status.

The inscription at the top of the painting misidentifies the figure of Jawan Singh as his father Bhim Singh but the features are clearly those of Jawan Singh who is easy to recognize.

For another painting of Jawan Singh in an interior setting receiving a noble, see Christie’s 10 May 2018, lot 1016. R. Ellsworth et al., The David and Peggy Rockefeller Collection: Arts of Asia and Neighboring Cultures, New York , 1993, vol III, p. 296, no. 225.

Attributed to Pannalal Rajasthan, Udaipur, Mewar, circa 1905

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Folio 13 ½ x 10 ¹⁄₈ in (34.2 x 25.7 cm)

Painting 10 ⁷⁄₈ x 7 ⁵⁄₈ in (27.6 x 19.4 cm)

The nimbated Maharana Fateh Singh (1849, r. 1884-1930) stands facing a courtier. Two attendants stand behind him on an elaborate floral carpet. Both attendants hold cauris or yak-tail flywhisks. Fateh Singh has his right hand resting on a sword and grips a shield with his left. He has a ram-headed dagger tucked into his patka or sash. The courtier facing him has his hands in a position of greeting and has a shield on his back. Details are all carefully rendered with bold outlines. The four men are placed against a bright green background with pink and blue washes at the very top representing the sky.

Unlike earlier Mewari paintings that depict rugs from above, here the rug suggests depth and spatial progression. The way attendants are placed on the rug also suggests a sense of space. All the men wear white jamas and similar patkas or sashes and pagris or turbans, with Fateh Singh wearing more jewelry and an elaborate turban jewel, or sarpesh

Compare this painting to Bonhams 18 October 2016, lot 305, attributed to Pannalal where the portrait of Fateh Singh is virtually identical.

Rajasthan, Marwar, Jodhpur, circa 1775

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Painting 11 ³⁄₈ x 9 ½ in (28.9 x 24.1 cm)

Bijay Singh (1729, reigned 1752-93) had one of the longest reigns of any of the Jodhpur rulers, but his rule was not a particularly successful one. According to Colonel Tod’s account, Jodhpur lost both territory and population during his reign, however the art of painting did flourish.

Bijay Singh is clearly the focus of this painting with his large figure dwarfing the horse and his smaller retainers. Against a pale green background Bijay Singh sits rigidly astride his caparisoned horse and is accompanied by three attendants. Standing behind the horse, one carries a stiff morchal, a peacock feathered flywhisk, while another one strides in front holding a staff. The Maharaja is dressed in a white diaphanous jama and dons an elaborate pagri or turban. He has a gold punch dagger or katar tucked in his patka or sash.

The hilt of a sword and the top of a black shield are evident from his left side. He is rather modestly dressed but the dramatic shape of his sideburn and elaborate pagri or turban add a regal quality to the whole.

For a discussion of Bijay Singh’s reign, see: Rosemary Crill, Marwar Painting, a History of the Jodhpur Style, Mumbai, 2000, pp. 98-108.

For a similar equestrian portrait of Bijay Singh, see Robert J. Del Bontà, Courtesans and Kings, Indian Paintings from Art Passages , San Francisco: ePress Books, 2008., no. 29.

Rajasthan, Marwar, Jodhpur, circa 1795

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Painting 12 x 9 ½ in (30.5 x 24.1 cm)

Inscribed in Devanagari:

Rājarāje sura māharājādharāja Śrī Śrī Bhīva Sīga Jī rī

Jodapar pasāprārāje?

Bhim Singh (?, r. 1793-1803) was the Maharaja of Marwar Kingdom. Bhim Singh seized Mehrangarh and proclaimed himself ruler in place of his grandfather on 13 April 1792. On 20 March 1793, he surrendered and retired to his personal jagir at Sawana but again seized the fort and proclaimed himself ruler for the second time on 17 July 1793. He spent his entire reign contesting the succession with his uncles and cousins. He managed to have most of them killed, leaving only Man Singh (1783, r. 1803-43) who succeeded him.

Sitting on a spirited horse, Bhim Singh towers over groups of retainers depicted in different sizes. The ones in front carry staffs while the group behind the horse carry tall spears. Another spear crisscrosses a standard decorated with a large symbol of the solar Rajput’s, a golden disk on a black background representing the sun. Other attendants carry cauris and morchals, flywhisks made of yak-tail and peacock feathers. This is a softer, more animated portrait than that of his grandfather, no. 10, and is drawn in a looser and energetic style. Bhim Singh wears elaborate jewelry consisting of gold, pearls and emeralds and a bejeweled turban.

See: Rosemary Crill, Marwar Painting, a History of the Jodhpur Style, Mumbai: India Book House Limited, 2000, pp. 109-13 for paintings during his reign.

Rajasthan, Mewar, Udaipur, circa 1760

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper

Folio 12 x 16 in (31.5 x 42 cm)

Painting 11 x 15 in (28 x 39 cm)

Maharana Ari Singh uses a popular technique for hunting exclusive of the nobles: falconry. Astride a rather determined, richly decorated stallion, he releases the bird from his gloved right hand and stretches his left hand suggesting the movement of the bird as it flies off. We see the bird three times in continuous narration; it flies towards its prey; it attacks it, and the two birds fall to the ground. The other birds. egrets or herons, make their escape.

The royal Ari Singh is accompanied by two men on foot who gesticulate in wonder at the success of the peregrine falcon. It all takes place in rolling hills suggestive of the setting of Ari Singh’s capital, Udaipur, on the side of Lake Pichola, with its marble architecture sporting cupolas like so much of the architecture there.

For a similar painting of Ari Singh hawking on foot see Andrew Topsfield, Paintings from Rajasthan in the National Gallery of Victoria , Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1980, no. 159. His attendants are in similar poses of wonderment.

West Bengal, Kolkata (formerly Calcutta), Kalighat, late 19th century

Ink and opaque watercolor on paper

Painting 17 ¾ x 10 ¾ in (45 x 27.3 cm)

Karttikeya is one of the sons of Shiva and is known by a wide variety of names including Skanda, Subrahmanya, Shanmukha, and Murugan, and is the Hindu god of war. The various names are due to a syncretization of gods from different traditions throughout the subcontinent. His birth is described in several ways. One is that Shiva spilled his seed, and the seed was preserved by the heat of Agni, the god of fire. He was raised by the Krittikas who we know as the Pleiades, hence his name Karttikeya “of the Krittikas.”

This composition is typical in the art of the Kalighat temple. Karttikeya is usually depicted with six heads with his vahana or vehicle, the peacock, and holds a spear; however, at Kolkata he usually has one head and sits astride the peacock whose foliage fans out behind him. He holds a small spear in his right hand and places his left hand at his waist. Curiously, he wears a Prince Albert hairstyle and English-style hat and pumps. The artist uses flat contrasting colors and heavy arbitrary shading that accents his chest, arms, and curve of his cheeks.

Similar paintings are in the Cleveland Museum of Art, 2003.151, the Penn Museum, Philadelphia, 29-225-28, and see Christie’s 20 March 2008, lot 317.

Rajasthan, Nathadwara, circa 1850

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on cotton Painting 70 x 58 in. (178 x 147 cm)

This cloth painting, a simhasana, represents the festival of Gopashtami celebrating the graduation of Krishna from a herd-boy, who took care of calves, to a full-fledged, mature cow-herder. This picchavai is called a simhasana due to the peaked top that mimics the back of a throne. Other simhasanas do not have a lot of figures since they are actual throne covers. The main image itself relates to an important scene during Krishna’s life, his arm is raised in the form of lifting Mount Govardhana to protect the cowherds and cows from a torrential downpour. Mount Govardhana was where the statue of the swarup (selfmanifesting) Shri Nathji was found.

Here Shri Nathji wears clothes that are constantly changed to correspond to times of the day and according to the religious calendar. He wears a flared skirt, scarves and lotus garlands and sports a cow-herd’s cap surmounted by the moracandrika, a peacock crest on the headdress. At the bottom, at Shri Nathji’s feet, are several auspicious objects. These are a banta (snack box filled with sweets — laddus), pan-bida (a pair of folded betel leaves) and a jhari (decorated water jug) filled with Yamuna water (the Yamuna is associated with the region of Krishna’s formative years). One must recall that the self-manifested image of Shri Nathji is treated as a living person, so these are necessary treats for him. These items are common to even the simplest paintings of the image of Shri Nathji.

By keeping the image in the gesture of lifting Mt. Govardhana or in the pose of the young cowherd playing the flute, the living narrative is never far from the minds of the devotees. Other paintings at Nathadwara depict exploits of Krishna, particularly ones that have to do with his boyhood.

Shri Nathji is after all a small child and not the fully grown romancer and hero as seen in so many depictions of Krishna.

At the top gopis (cowgirls) flank the figure of Shri Nathji in the pichhavai within the simhasana

The picchavai has vertical rows of cows running up the two sides and peacocks across the top in a narrow band and is placed before a starstudded sky although the festival takes place in the afternoon during Sharada (Autumn). The gopis hold up their hands in praise. Cows with two gopas, cow herders, take up the middle register and four more gopis are below standing along a pink-lotus decorated Yamuna (Jumna) River at the very bottom. The whole displays a rather formal symmetry with the two sides basically mirroring each other.

For other examples of this festival see: Robert Skelton, Rajasthani Temple Hangings of the Krishna Cult , New York: Federation of Arts, 1973, no. 17, p. 64-65.

Kay Talwar and Kalyan Krishna, Indian Pigment Paintings on Cloth, Vol. III, Historic Textiles of India at the Calico Museum, Ahmedabad, Bombay: Vakil & Sons Limited, 1979, nos. 45-54, pls. 47-55a. Throne covers: no. 60 pl. 57; no. 69, 65A; no. 73, pl. 68; no. 83, pl. 73; and no. 91, pl. 79

Madhuvanti Ghose, ed., Gates of the Lord: The Tradition of Krishna Paintings , Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 2015, pp. 27, 31, 129 and cat. No. 63.

Rajasthan, Nathadwara, circa 1850

Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on cotton 66 ½ x 54 ¼ in.

The festival of Annakuta commemorates Krishna raising Mount Govardhan with the mound of rice symbolizing the mountain. Annakuta (the Mountain of Food) commemorates when Krishna persuaded the villagers of Vraj to present their autumn harvest to the hill spirit of Mount Govardhana.

The main image of Shri Nathaji and other statues of Krishna swarupas are depicted on the altar of the temple at Nathadwara, one of the most vital living temples in northern India. In the center we find Govardhana puja (essentially a small version of Annakuta), and Dana Lila (the toll of curds). A huge pile of rice and vessels full of food are placed below the images while two of the main priests of the temple flank the images at their level. The one on the left holds a lamp and performs a ritual called arati. Vallabhacharya (1478-1530), the founder of the Pushtimarga sect and his son Vitthalnath and others sit below. Below them are the sons of Vitthalnath. Flanking the main Shri Nathji image are depictions of the shrines for the six images Vitthalnatha distributed to his sons. The hundreds of portrait circles (608) surrounding the scene represent the descendants of Vallabha and the lineages are connected by red and yellow lines from each of their individual swarupas.

The lower register is painted with scenes from his daily life of Shri Nathji within the Nathdwara complex. To the left the toddlers, Shri Nathji and Balarama, sit in the laps of Nanda and Yashoda, Krishna’s foster parents. In the center we find Govardhana puja (essentially a small version of Annakuta), Dana Lila (the toll of curds). To the right is the figure of Balarama with his wife Revati. Below the puja and Dana Lila, a gopa (cowherder) and cows line at the banks of the Yamuna (Jumna) River.

Kalyan Krishna and Kay Talwar, In Adoration of Krishna , Pichhwais of Shrinathji, Tapi Collection, Surat and Mumbai: Garden Silk Mills and New Delhi: Roli Books Private Limited, 2007, no. 28, pp. 102-04.

Robert Skelton, Rajasthani Temple Hangings of the Krishna Cult , New York: Federation of Arts, 1973, nos. 1415, pp. 58-61.

Madhuvanti Ghose, ed., Gates of the Lord the Tradition of Krishna Paintings , The Art Institute of Chicago, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015, no. 60, p. 125.

Kay Talwar and Kalyan Krishna, Indian Pigment Paintings on Cloth, Vol. III, Historic Textiles of India at the Calico Museum, Ahmedabad, Bombay: Vakil & Sons Limited, 1979, nos. 38 and 40, pls. 43-44 and other plates without the lineage.

16 Jagannatha, Balabhadra, and Subhadra as Rama, Lakshman, and Sita

Odisha (formerly Orissa), Puri, circa early to mid-20th Century

Ink and opaque watercolor on cotton 19 x 23 ⁵⁄₈ in (48.4 x 60 cm)

The image of Jagannatha (meaning Lord of the Universe) is unusual since it is a stump of wood with no arms or feet. It is likely a figure with tribal roots in Odisha which was later co-opted and incorporated into Hindu devotion and associated with Vishnu, usually Krishna; however, he is also associated with other avataras of Vishnu, including Vamana during the month of Bhadra. He is usually depicted as a Triade along with his brother Balabhadra (or Balarama) and his sister Subhadra. He is the figure on the right with a black face and large circular eyes. Although the actual icons do not have limbs, merely stumps sticking out from the pillar-like figures, the artist has added them to all three figures here. In fact, the artist has given Jagannatha and his brother four arms each. Both hold a bow and arrow associating them with the avatara Rama and his brother Lakshman. Balabhadra also holds an ankusha (elephant goad) and a rod. Jagannatha holds a diminutive cakra (discus) and shanka (usually called a conch in the literature). Subhadra holds a padma (pink lotus) and has her right hand on her hip. The male figures sit with their legs folding into a half lotus.

The association of Jagannatha with Rama probably relates to the visit that the Hindu saint and poet Tulsidas (1511–1623) made in the 16th century. Tulsidas worshipped him as Rama and called him Raghunath.

The figures in the white frieze at the base include two winged Garudas, the rishi Narada, another rishi, Shiva, and a kneeling figure. Underscoring the clear association with Rama, others include a standing monkey and a large Hanuman touching Jagannatha’s toe.

For a related image of the trio with human limbs, see Philadelphia Museum of Art 2008-116-1.

Odisha (formerly Orissa), Puri, circa 1960s

Ink and opaque watercolor on cotton 18 x 18 in (45.5 x 45.5 cm)

Jagannatha, Balabhadra, and Subhadra appear above seated figures of priests along with plates of offerings to the deities. Other figures worship at the feet of the gods and goddess. All is placed over the depiction of a shankha shell, often referred to as a conch although it is a different shell altogether. The various avataras of Vishnu usually hold these shells, the most important one named Panchajanya, features often in the stories of Krishna. Unlike number 16 in the catalogue the figures have short arms without hands which are closer to the actual wooden statues in the temple at Puri. The circular form is reminiscent of ganjifa, a popular card game in Puri.

For other related round images of the trio with similar iconography, see Philadelphia Museum of Art 1972-237-18 and 1994-148-575.

17 Jagannatha, Balabhadra, and Subhadra

Odisha (formerly Orissa), Puri, circa mid-20th Century

Ink and opaque watercolor on cotton 20 ³⁄₈ x 18 in (51.5 x 45.5 cm)

In an elaborate temple-like setting the eightarmed Durga as Mahishasuramardini stands on the backs of a lion and a buffalo and looks out at the viewer with her arms fanned to each side. She is sumptuously dressed in her regalia and carries a weapon or an attribute in each of her ten arms. The demon Mahisha kneels below her with his arms stretched to the sides holding a sword and shield. He has just emerged from the severed neck of the green buffalo and Durga’s vahana takes a bite out of his right knee. This static depiction shows Durga before she kills the demon rather than depicting her in the dramatic act itself.

In an opulent interior, the deity is flanked by elaborate white columns, each surmounted by a head of a Makara and supporting a cusped ceiling decorated with green drapery. A pair of flying apsarases flank the tiered temple tower each holding a garland. The whole is encircled with a twisted serpentine-like border.

For a related image of Durga from Puri, see Philadelphia Museum of Art 1995-151-2.

Karnataka, Mysore, circa 19th century

Opaque watercolor and gold on stiff paper 46 cards at 2 ¾ in (7 cm) or less in diameter

The Ganjifa card game is believed to have originated in Persia and was established in India in the 16th century when it was popularized by the Mughals referred to as Mughal Ganjifa which had eight suits of twelve cards each.

The playing cards were called Chada in Mysore where Mummadi Krishnaraja Wodeyar (1794-1868) devised several elaborate board and complicated card games, some with up to eighteen suits, one with a pack of 360 cards. The games are described in the last chapter called Kautukanidhi (treasure of games and pastimes) of the Shritattvanidhi, a long treatise by the king covering all sorts of topics from various forms of the gods, each in a separate treatise, yoga, music, etc. Many of these games may only have been played at the palace.

One group of cards here consists of part of a twelve-suit deck, each representing a sign of the zodiac. Each of the cards depicts a deity seated atop a symbol representing the sign of the zodiac. Clearly, these come from a few known sets of what are called Rashi Ganjifa, Rashi being the Indian name for the signs of the zodiac. The player would have to take the whole image into account without the number of details known in the Mughal ganjifa deck, which had the two court cards, and the rest of the cards had the suit symbol from one to ten.

Here presumably there is a progression with the most powerful gods down through to the lesser ones. The hierarchy is unclear, but one can see that the same god is found with several signs of the zodiac. A player would have to take in the specific god and the sign for the zodiac below. For instance, the Vishnu incarnation Vamana, the figure holding a lota or pot and umbrella, is seen five times from different suits: Cancer, Scorpio, Pisces, Virgo, and Leo.

The other group of cards are from a different pack representing one of Mummadi Krishnaraja Wodeyar ganjifa games. The suits appear to be the conveyances upon which the gods ride. There are suits of palanquin, horse, throne or chair, elephant, chariot, and flag. This group also includes suitless cards called cakravarti. These are the three that have cusped edges: Shiva, Devi, and birds. These appear to be only in some of Mummadi Krishnaraja Wodeyar’s games and presumably acted like trump cards in western card games.

Odisha (formerly Orissa), Puri, circa mid-20th Century

Opaque watercolor and shellac on cloth 65 cards at 2 ¾ in (7 cm) in diameter

The most popular Indian card game that evolved from the eight-suited Mughal Ganjifa pack is the ten-suited Dashavatara set with a suit for each of Vishnu’s ten incarnations. Often the pack is extended to twelve and includes a suit for Ganesha and Karttikeya. This partial deck includes the main card for the first five of the avataras (Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Narasimha, and Vamana) along with a few court cards. These are the ones with figures in chariots. One of those is from the Karttikeya suit with him mounted on a peacock.

The numbered cards have symbols for each of the avataras: fish, tortoises, shanka or conch, cakra or discus, lota or pot and Karttikeya’s peacocks.

For a related group of Dashavatara cards, see Philadelphia Museum of Art 2009-210-1 through 2009-210-9.

1.415.690.9077 info@artpassages.com www.artpassages.com