FALL 2022 PO-TAY-TOES! BOIL 'EM, MASH 'EM, STICK 'EM IN A VODKA Can YOU DO IT? THERE AND BACK AGAIN: DRY FLY DISTILLING 10 YEARS LATER cheers TO 10 YEARS

BRAND STRATEGY | STORY DEVELOPMENT | NAMING LOGOS | PACKAGING | CUSTOM BOTTLES | PRINT | DIGITAL DRINK WITH YOUR EYES ® 2787 NAPA VALLEY CORPORATE DR, NAPA, CALIFORNIA 94558 T | 707 265 1891 WWW.CFNAPA.COM CFN216_ArtisanSpiritsAd_2_ FALL_2022.indd

TABLE of CONTENTS

QUARTERLY GUILD & INDUSTRY REPORTS 13

Updates from guilds and associations within states, across the nation, and beyond!

BOOTSTRAPPING YOUR BRAND — WHAT YOU REALLY NEED TO HAVE FOR LAUNCH 33 Brand Buzz with David Schuemann

THE SCIENCE OF SULFUR: METHYL THIOACETATE GENERATION AND CONTROL 37 From the Good Guy Distillers

DISTRIBUTING THE COMPETITION AMONG DISTRIBUTORS 41

Executive order aims to compel competition

MASH FILTERS ARE YOUR FRIEND 45

A humble brewers' tool

TRADEMARK APPLICATION CONSIDERATIONS 49

For alcohol beverage brands

TEN PRODUCERS REFLECT ON A DECADE (OR MORE) IN CRAFT DISTILLING 52 It's a party, and everyone's invited

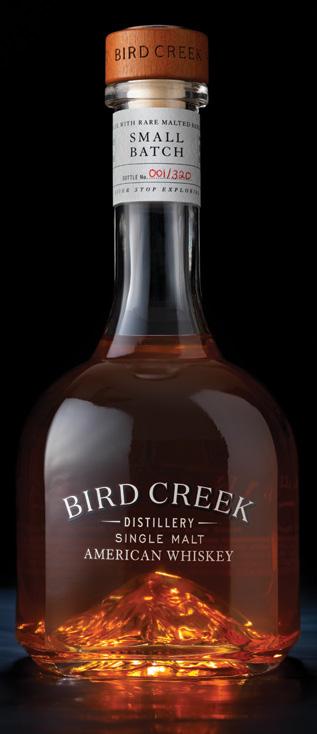

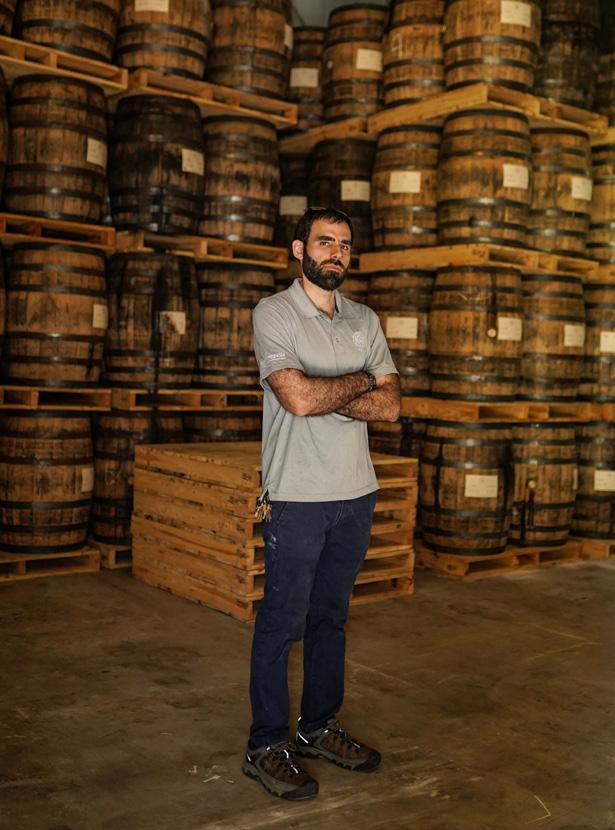

DRY FLY DISTILLING 58 of Spokane, Washington

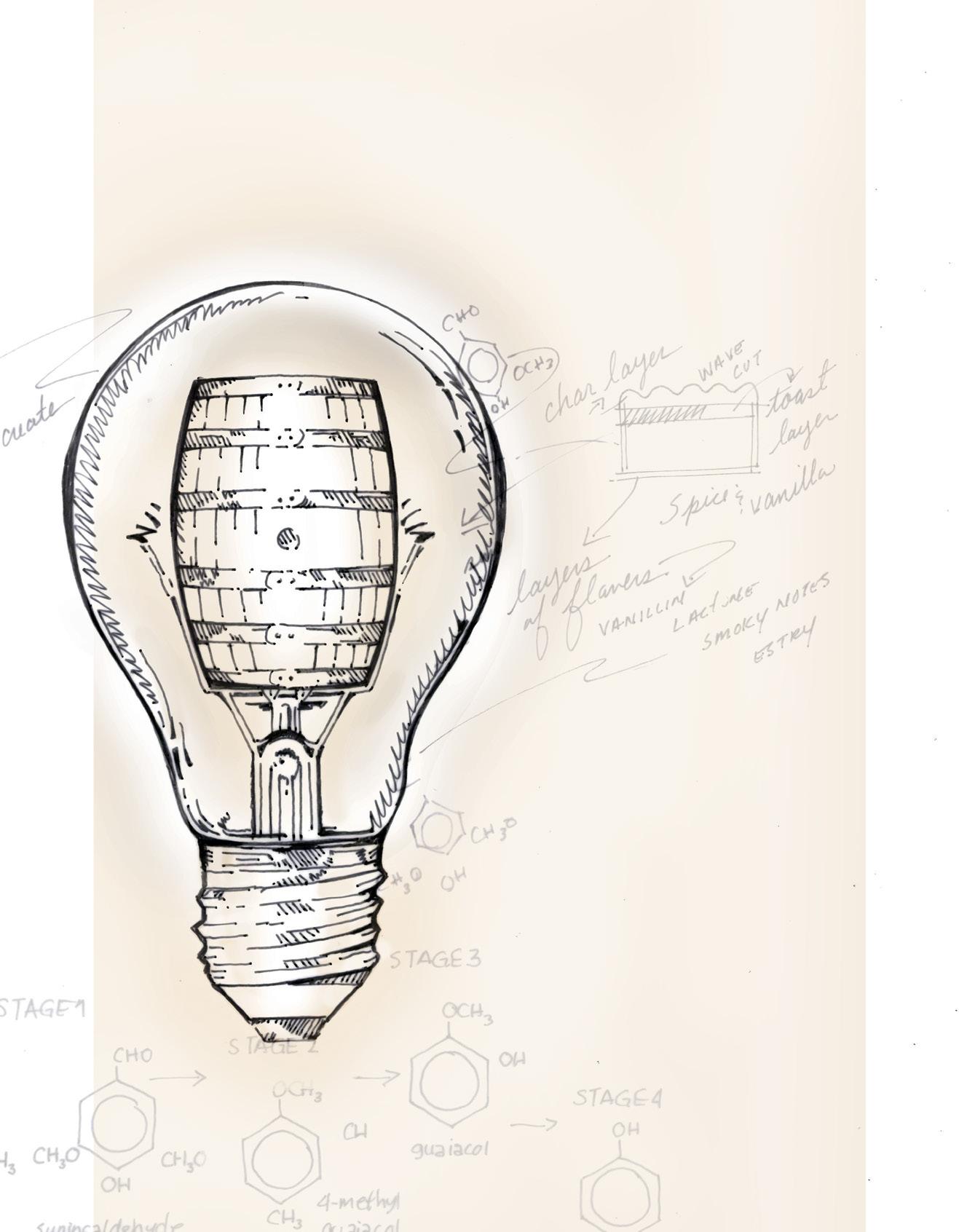

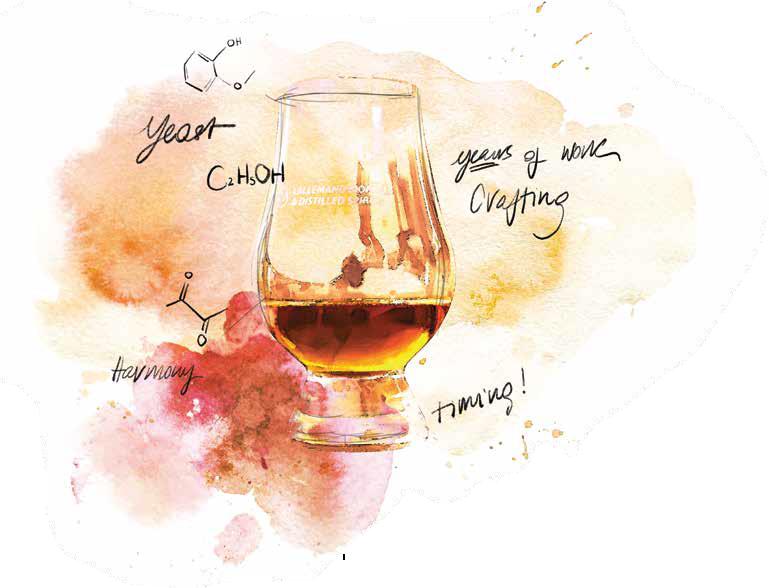

YEAST 63

Dissecting the flavor contribution of yeast

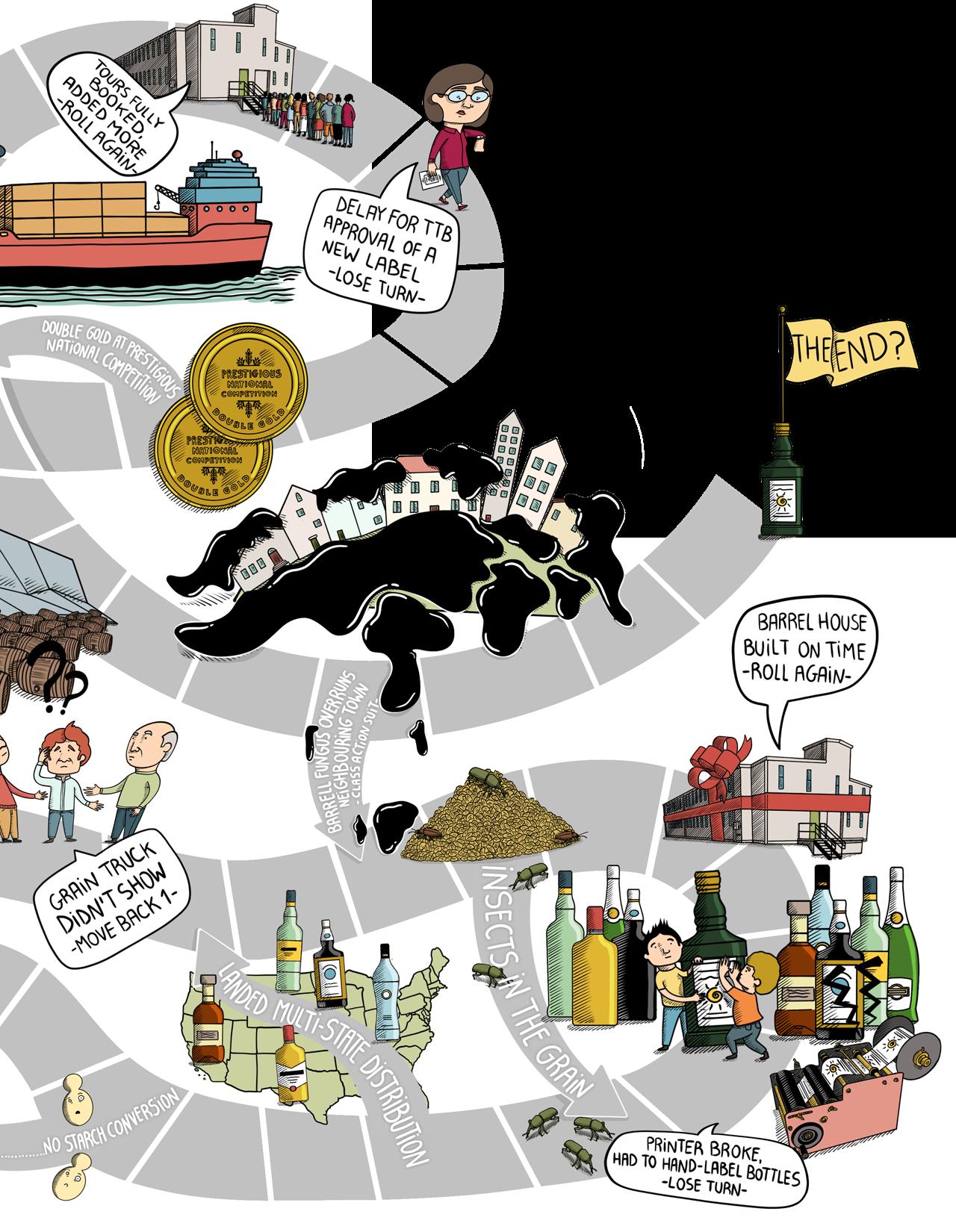

THE DISTILLER'S LIFE 66

A board game created just for you, just add dice!

FAIR GAME SHINES A SPOTLIGHT ON NORTH CAROLINA AGRICULTURE 68 Beyond the Bottom Line

A DECADE OF GIN 73 A ten-year retrospective

THE POWER OF PREGNANCY 77 How to grow a human and make whiskey: A guide

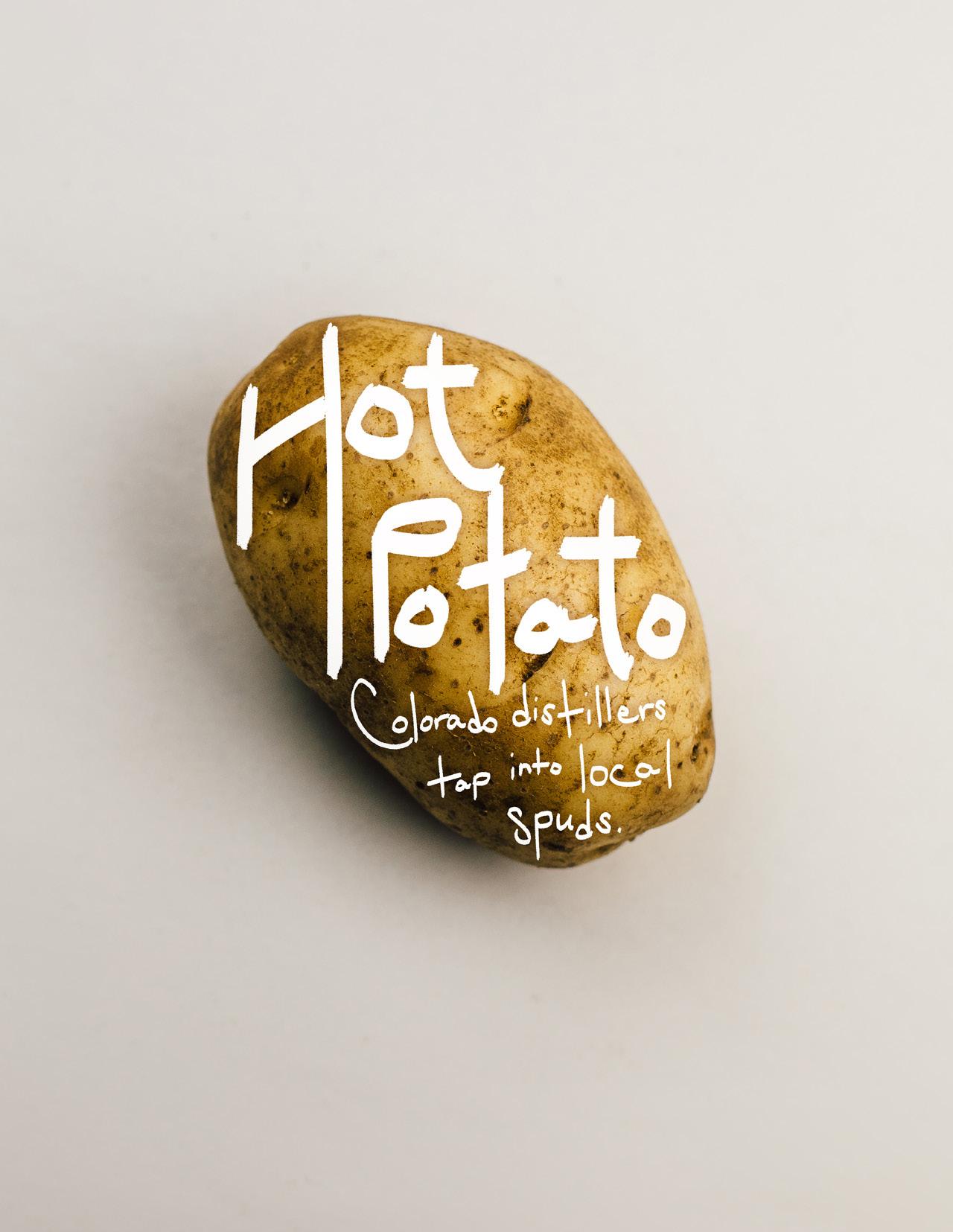

HOT POTATO 80 Colorado distillers tap into local spuds

THE GRASS IS GREENER FOR PUERTO RICO’S SAN JUAN ARTISAN DISTILLERS 84

A family business looks to rum’s future after a tumultuous decade

DEFINING A DECADE 88 What’s in craft

WHEN IT COMES TO SPIRITS AND COCKTAILS PRODUCTION, SHOULD YOU CAN IT? 92 Aluminum cans: steeling the way forward

THE AGE OF (DISTILLED SPIRITS) ENLIGHTENMENT 95 The inevitability of change

WHAT A DIFFERENCE A DECADE MAKES! 100 “There ain’t no laws when you’re drinking Claws.”

COMMUNITY BUILDING TAKES TIME 104 Jason Barrett reflects on Black Button Distilling's first 10 years

NO ALCOHOL, NO PROBLEM 106 Wilderton’s N/A spirits stand out on their own

MORE ON THE NEW WORLD OF FEDERAL EXCISE TAXES 109 Changes to the The Taxpayer Certainty and Disaster Tax Act of 2020

DISCUS, EPA PARTNER TO RELEASE ENERGY STAR GUIDE FOR DISTILLERIES 111 A new sustainability tool emerges

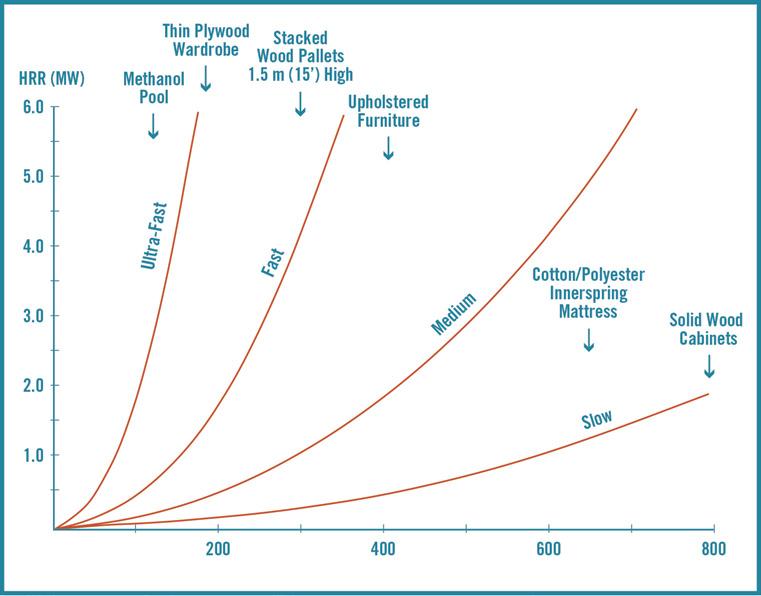

IT’S PARTY TIME — INTRODUCING HIGHER OCCUPANCIES 114 Fire and Life Safety Corner

THE SOUL OF SPIRITS 117 Bar Convent Brooklyn 2022 highlights why distilling matters

THE HISTORY OF PRE-MIXED DRINKS 120 The rise of the cocktail

BIG EXCITEMENT IN THE BIG EASY 122 The 2022 DISCUS Conference proves the industry is stronger together

EMERGING TREND: INCUBATOR BUSINESS MODEL 125 A new business model for craft

LETTER BAG 128

ADVERTISER INDEX 130

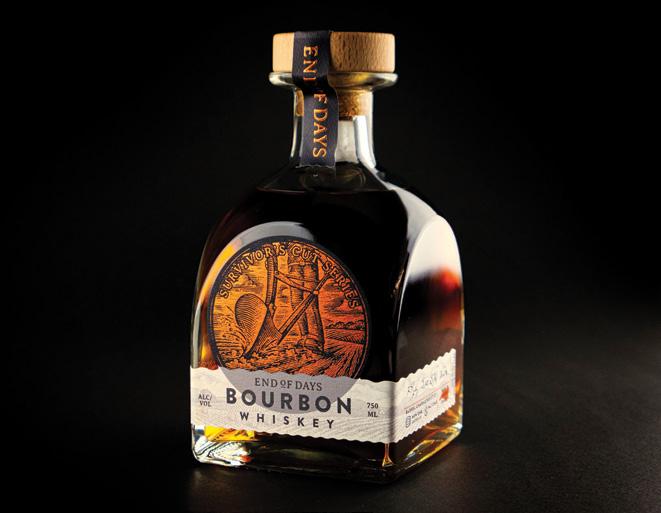

from the COVER Dry Fly Distilling in Spokane, Washington. Image by Amanda Joy Christensen. See their story on page 58

40

PUBLISHER & EDITOR Brian Christensen

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Amanda Joy Christensen

SENIOR WRITERS

George B. Catallo Devon Trevathan

CONTRIBUTORS

Luis Ayala

Shane Baker Jason Barrett Corey Day Carrie Dow Chloe Fisher Doug Hall Harry Haller Ashley Hanke Pat Heist, Ph.D. Reade A. Huddleston, MSc. Paul Hughes, Ph.D. Aaron Knoll

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Amanda Joy Christensen Carrie Dow

Francesca Cosanti

David Letteney

Rich Manning Jim McCoy

Michael T. Reardon, P.E. David Schuemann Gary Spedding, Ph.D. Grady Szuch

John P. Thomas Gabe Toth, MSc. Molly Troupe

Lisa Truesdale Margarett Waterbury

Ayano Hisa Carey McKelvey

ARTISAN SPIRIT

Ashley Monroe

Artisan Spirit Media.

General Inquiries (509) 944-5919

31494, Spokane, WA 99223

(509) 991-8112

All contents ©2022. No portion of this magazine may be reproduced without the written consent of the publisher. Neither Artisan Spirit Media nor ARTISAN SPIRIT magazine assume responsibility for errors in content, photos, or advertisements.

While ARTISAN SPIRIT makes every effort to ensure accuracy in our content, the information is deemed reliable but not guaranteed. We urge our readers to consult with professional ser vice providers to meet their unique needs.

At ARTISAN SPIRIT, we take the opportunity to enjoy many different craft spirits and adult beverages. However, it’s also our responsibility, and yours, to always drink responsibly. Know your limit, and never drink and drive.

ARTISAN SPIRIT’s number one goal is to share and celebrate the art and science of artisan craft distilling. But please remember to follow all the laws, regulations, and safety proce dures. Be safe, be legal, and we can all be proud of the industry we love.

ISSUE

/// FALL 2022

ILLUSTRATOR

SALES & MARKETING

is a quarterly publication by

www.artisanspiritmag.com facebook.com/ArtisanSpiritMagazine ArtisanSpiritM ArtisanSpiritM

Advertising

PO Box

INNOVATIVE SOLUTIONS since 1912

A barrel should be more than an aging vessel, it should be a partner in achieving your desired flavor profile. Using science-based research and experimentation, ISC barrel experts collaborate with world-class distillers to create innovative barrel solutions for their unique spirits.

iscbarrels.com

THANK YOU TO ALL OUR SPONSORS.

The American Spirits Exchange is a national importer and distributor serving the alcoholic beverage industry (spirits, wine, and beer). We provide domestic and international companies with access and support to the U.S. market. Regardless of your size — from micro, craft distiller to publicly traded multinational — our focus fuels your growth. Our flagship Foundations™ program provides companies with access to the U.S. market. We handle your business-to-business functions from start to finish: permitting, brand approvals, purchase order processing, invoicing, and compliance.

Founded in Boulder, CO in 2016, Arryved is a point-of-sale based software company specializing in the food, beverage, and entertainment industries: distilleries, breweries, cideries, wineries, brewpubs, restaurants, and music venues. In five short years, it grew from being an idea scribbled on a taproom coaster to a revered platform serving over a thousand happy customers across the country.

Arryved is a team of tech geeks with relentless passion for, and extensive experience in, the hospitality industry, as both employees and consumers. The goal is simple: Deliver a flexible, reliable, team-centric platform that puts service first in every way.

Arryved’s flexible, all-in-one system simply makes business easier, so you can focus on enjoying life — distilling craft spirits, lifting up your staff, and creating core memories within your community. We’ll cover the rest.

Boelter is a strategic partner to the most successful distilleries, breweries, beverage distributors, wineries, and cidermakers in the country. With over 90 years of beverage industry experience, we provide guidance and essential promotional products to ensure that through every service and season, our partners are performing at their peak. Our key product categories include glassware, tap handles, coasters, cups, and barware, but we pride ourselves on our willingness to work hard to serve our customers — whatever their need may be. We are passionate and enthusiastic because we believe we have a purpose that transcends the day-to-day work that we all do.

Montanya Distillers, Headframe Spirits, and Maker’s Mark. Seems like an odd list, right? Well, they are all certified B Corps. It’s not easy to make it in the spirits world much less do it while being mindful and transparent about staff, process, and environmental impact. — Colin Blake

Hanson Distillery. When developing their product, they allowed themselves over 100 attempts to achieve their final formula of grape varietals for their organic vodka. Their tasting room and distillery are perfectly situated on a vineyard in picturesque Sonoma Valley, lending to an incredible customer tour and tasting experience.

Which distilleries have impressed you recently and what could their peers learn from them?

Our mission at Artisan Spirit Magazine is to share and celebrate the art and science of artisan craft distilling.

6 WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM

We are humbled by the support of our sponsors. With their help, we can further our common goals of supporting creativity, innovation, and integrity within the industry we all love so much.

BSG is focused on supplying craft distillers with the best ingredients from around the world. The craft distilling market trusts BSG to deliver the finest ingredients at competitive prices, without sacrificing customer service. With distilling malts and grains from Rahr Malting Co., Weyermann®, Simpsons, Crisp and Malting Company of Ireland, as well as a full range of yeasts, yeast nutrients, enzymes, botanicals, and finishing products, we have a wide range of distilling ingredients to help you create high quality, artisanal spirits.

Cage and Sons Distilling Systems build premium distillation systems and equipment for premier distilleries.

Every element of Cage and Sons equipment is designed and crafted to provide you with the very best distilling experience at an affordable rate because we know that bottom line matters, but so does function. At Cage and Sons, adequate is never an option, and we continue to develop and design new high functioning, cutting-edge distillation systems that enhance the distillation industry. Cage and Sons works every day to bring you the very best distillation systems for the very best value.

Unlike other agencies that work within a blinding myriad of industries; our focus is 100% within the spirits, wine, beer, and other alcohol sectors. This specialization has allowed us to become experts in the alcohol beverage category. We have an exceptional understanding of design that sells, complemented by professional project management and flawless production oversight. The result has been strategic solutions that consistently produce both critical acclaim and strong measurable return on investment for our clients.

The Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (DISCUS) is the leading voice and advocate for distilled spirits in the United States. Representing producers and marketers of distilled spirits, DISCUS advocates on legislative, regulatory, and public affairs issues impacting the distilled spirits sector at the local, state, federal, and international levels; promotes the distilled spirits sector, raising awareness and opening markets in the United States and around the globe; and encourages responsible and moderate consumption of distilled spirits as part of a healthy adult lifestyle based on evidence-based research and policy. DISCUS also powers Spirits United, a grassroots platform for the distilled spirits industry. Spirits United is comprised of a community of advocates united with a common goal: to ensure adult consumers can enjoy distilled spirits where they want, how they want, and when they want. Learn more at distilledspirits.org and spiritsunited.org.

Trusted Oak Expertise Since 1912.

We’ve been in this industry for over 100 years, during which time we’ve learned a thing or two about what makes a great barrel to age great spirits. Our R&D team and account managers have hundreds of barrels currently in experimentation. Partnering with distillers, we think outside the box to develop new products that push your vision forward.

Our Mission: To craft world-class oak barrels and other cooperage products so our employees, customers, and communities flourish.

WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM 7

Lallemand Biofuels & Distilled Spirits is the industry leader in supplying fermentation products and valueadded services to the distilled spirits industry. We specialize in the research, development, production, and marketing of yeast and yeast nutrients as well as a solid belief in education of the distilled spirits industry.

A vital part of the alcohol production process, fermentation products from Lallemand Biofuels & Distilled Spirits have been designed and selected to create value by tailoring objective solutions to distillery needs.

Standing out in a crowded marketplace is an ongoing challenge for wine and spirits producers today. MCC’s experienced team of label engineers take a consultative approach, helping guide your project from inception to finished label. Whether it's an existing design, or a highly embellished new project, we are poised to give your brand the look it deserves. Housing many different printing technologies under one roof allows us to match our passion and expertise to your project, each and every time, without compromise. This ensures that your final packaging always achieves the desired look. With MCC and Fort Dearborn recently joining forces, we are poised to provide all spirits customers with amazing service and quality products.

Southern Distilling Company is one of the largest artisan distilleries in the nation. We offer product development, contract distilling (standard and custom mash bill whiskeys, rum, and agave spirits), barrel warehouse aging, batching, blending, bottling, and co-packaging of award-winning products. We also keep an extensive inventory of aged bourbon and rye whiskey available year-round.

Our spirits are distilled in top-of-the-line Vendome Copper & Brass Works continuous column stills. Our product development services include working with you to perfect an existing recipe and consultations to help you create your own recipe. We can barrel and warehouse age your product to meet both short and long-term goals. At Southern Distilling Company, you get standout spirits that make brands unforgettable.

For over 60 years Tapi USA has produced cork stoppers and a wide variety of bottle closures. Family-owned and operated since its inception, our company continues to develop new products and enter new markets. Tapi USA is proud to support the growth of the artisan distillery industry and is honored to be the Bottle Closure Sponsor for Artisan Spirit Magazine.

Total Wine & More is the country’s largest independent retailer of fine wine, beer, and spirits. Our strength is our people. We have over 5,000 associates, who must demonstrate comprehensive beverage knowledge before they are invited to join our team. After coming on board, all of our team members undergo an extensive initial training program. We believe that an educated consumer is our best customer. We want to demystify the buying experience for our customers so they will feel confident in choosing the bottle that is perfect for them. Total Wine & More works closely with community and business leaders in each market it operates to support local causes and charitable efforts.

8 WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM

A LETTER FROM THE EDITOR:

What the hell are we doing?

I think I can finally answer that question. Perhaps not with absolute confidence, but that’s never really stopped us from trying.

That question, which appeared in our very first issue of Artisan Spirit Magazine 10 years ago, has been a guiding mantra for our inde pendent trade publication. It was a question we asked ourselves, but more importantly it was the question our readers were asking themselves. Hundreds of new entrepreneurs jumping into a fledgling craft industry where the art and science of distilling were common ly shrouded in mystery and misinformation.

At the time we were four outsiders talking about starting a distillery, and quickly real ized we were completely inept and ignorant. Luckily we had a wide range of skills we could blindly throw at a new idea. Graphic design, web development, sales, and whatever it is I do (I talk to people, mostly).

Like so many startups the ideas morphed into something different. In our case, the business became a trade publication. A print trade publication. Oh, and we wouldn’t allow paid “advertorials,” and we would always pub lish more content than advertisements, and then we would give a copy to any distiller in America for free!

Yes, we were very idealistic, but somehow the ethics stuck. More importantly, those ideals resonated with an audience. We found ourselves surrounded by like-minded people who forgave our naivete and embraced the sincerity that drove us.

Within a year the team running Artisan Spirit was a core group of three friends: Editor Brian Christensen, Creative Director Amanda Christensen, and Director of Sales and Marketing Ashely Monroe. Within two years Artisan Spirit Magazine was our full

time job, backed by an incredible group of talented writers, academics, and distillers all around the world.

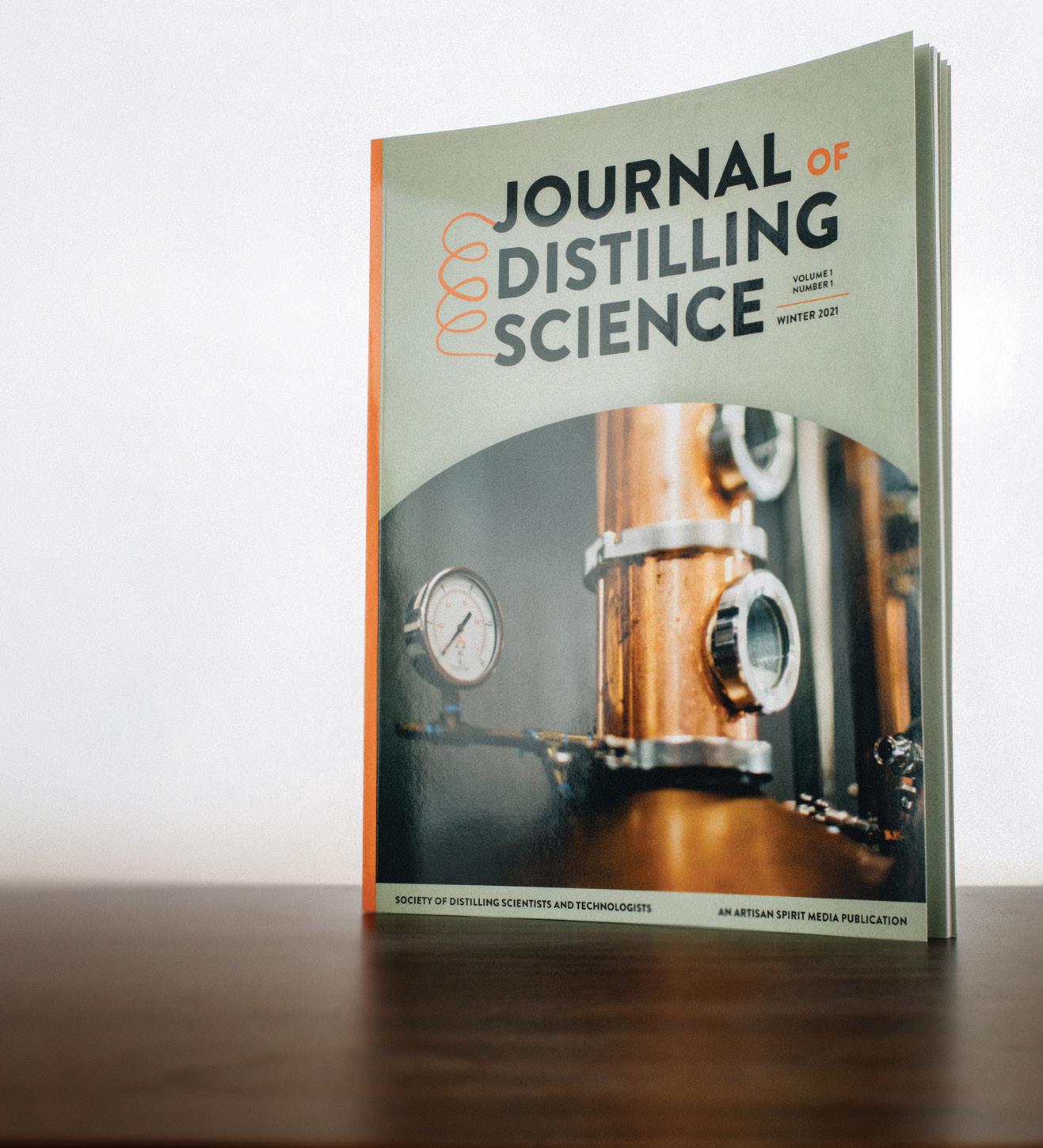

Over the course of 10 years Artisan Spirit Magazine has gone from a 36-page “pam phlet” to a respected 100+ page quarterly journal, distributed in 44 countries, read by almost every DSP in the United States, and now publishing a companion peer reviewed scientific journal (Journal of Distilling Science) and a wildly irreverent podcast (the Still Talking Podcast).

None of this happened in a vacuum. It wasn’t just three scrappy friends who made this happen. It was a collection of industry mentors and organizations that bent over backwards to guide us and support our vi sion. People like Steven Faith, former VP of Spirits at Total Wine and More who said, and I quote, “You would be complete dumbasses not to make a magazine like that.” Or our first two sponsors, the “Jacks.” Jack Joyce, founder of Rogue Ales and Spirits who was my very first industry interview, and who classically said, “Anything worth doing should be done half-assed. If you can make it work by bare ly trying, it’s probably a good idea.” And Jack Vogel, then of St. Louis Litho, now of MCC Label, who was a consistent sounding board, advisor, and advocate for the educational po tential of suppliers.

So many people helped us and opened their doors without question. Complete strangers like George Manska of Neat Glass who offered to share his booth with us at an Oregon state trade show. Distillers like Don Poffenroth, our first cover story and fellow Spokane, Washington resident, John and Courtney McKee along with Johnny Jeffrey who would eventually go on to form the Good Guy Distillers, Ted and Dana Huber who invited us into their homes and distillery year after year, and godfathers of the industry like Ralph Erenzo and Jimmy Russell who would take the time to share a drink and a sto ry with young nobodies like us.

There were the incredible industry pro fessionals like Leah Hutchinson and Penn Jensen who we randomly met in an elevator at an American Distilling Institute convention 10 years ago, and would soon go on to help form the American Craft Spirits Association. Also, Frank Colman of Distilled Spirits

Council of the United States (DISCUS) who just happened to be walking by during our first meeting of advisors in year two, and pulled up a chair to lively and graciously de bate what “craft” was.

Groups like the Kentucky Distillers Association, Washington Distillers Guild, American Distilling Institute, and DISCUS all welcomed us into the industry without question or pretense.

Not to mention those first few advertisers who answered Ashely’s cold call and then spent 40 minutes on the phone inundating us with ideas before asking us if they could ad vertise in a publication that didn’t even exist yet.

Most importantly, the readers, who picked up the phone or emailed with ideas and sug gestions. Always feeding us with positivity and encouragement to keep doing what we were doing.

Finally, because they rarely get a chance to speak up (did I mention I talk a lot?), I want to thank the true heart of this publication. My partners Ashley Monroe and Amanda Christensen. They are the best people I have ever known. It is impossible for me not to im mediately smile when I think of them. Hard working, clever, wildly creative, talented, gracious, and kind. They are my partners, my family, and my friends.

I could go on for several thousand more words thanking and recognizing the people who helped us, who continue to help us, ev eryday. I hope you know who you are, and please understand that you have made the last 10 years the most professionally and person ally rewarding decade of our lives.

So, what the hell are we doing? We are fos tering a community of scientists, artists, en trepreneurs, and fellow nerds. Sharing your stories, and welcoming the next generation of distillers into this industry with open arms.

With greatest appreciation,

(509) 944-5919 /// brian@artisanspiritmag.com PO Box 31494, Spokane, WA 99223

Brian Christensen

10 WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM

Sales@TheTierraGroup.com ww w TheTi er r aG r oup. c o m 1 . 844 . 825 . 828 2 O R GA N I C B L U E A G A V E G R O W N • H A R V E S TED • P R OD U CE D 100% ORGANIC BLUE AGAVE CONCENTRATE PREMIUM 100% BLUE AGAVE SPIRITS - USA 100% BLUE AGAVE TEQUIILA - MEXICO The Industry Standard for creating distilled agave spirits Distilled bulk Agave Spirits Bottled TEQUILA MIXTO - MEXICO AGAVE DISTILL - MEXICO Bulk Bulk, Great for RTD Products AGAVE SYRUP Bulk P E R F E C T I N G THE S PIRI T OF A G A V E

UPDATES FROM GUILDS AND ASSOCIATIONS WITHIN STATES, ACROSS THE NATION, AND BEYOND!

QUARTERLY GUILD & INDUSTRY REPORTS

State guilds are the most important organizational entities within the spirits industry. There, I said it, and I’d fight to the death to defend my mostly subjective opinion. In our experience it's the guilds that are consistently the front lines of regulations, legislation, consumer attitudes, and industry fortunes. More than national associations or news nerds like Artisan Spirit, the guilds know what's coming down the pipe before the rest of the industry. That's why it has consistently been the most-read, best-reviewed section of this publication since it debuted. Selfishly, it’s one of my favorite parts of Artisan Spirit, and we are delighted to set up the soap box for the state distilling guilds every issue. With that said, buckle up, because we have 14 guild updates in this anniversary edition of ASM. There is a lot to go over.

Brian Christensen Editor, Artisan Spirit Magazine

AMERICAN CRAFT SPIRITS ASSOCIATION

Fall is here, and so is election season in many places around the country. The American Craft Spirits Association (ACSA) would like to remind every distiller to connect with your elected offi cials at every level. They want to hear your feed back on policies and how market conditions are affecting you. 2022 has proven challenging for most members with supply shortages, increasing costs, and tightening margins. Both your state guilds and ACSA are working at every level to improve your business landscape, from advocat ing for more flexibility in packaging with TTB, to working with your state legislatures toward parity with wine and beer. The number of craft distilleries is increasing yearly, as is our political power, but we need distilleries to work together

to make progress happen. If you aren't already involved, dip your toes in the water either in a na tional committee with ACSA, or with your state guild — it's also a great way to connect with the community of fellow distillers on a personal level. Market access is still the primary challenge facing small independent distillers. The 2022 Craft Spirits Data Project results will be out in November, and over the past 10 years, distillery starts are up tenfold. In that same time, the num ber of wholesalers has decreased by a third due to consolidation. ACSA is working to help distillers understand and navigate this changing landscape with our distribution partners, while at the same time, working to improve access to the distri bution system by creating and improving ways

QUARTERLY REPORTS

13

to connect distillers with their customers through expanding access to direct-to-con sumer shipping and other tools available to breweries and wineries.

Look for more information on the advoca cy work of ACSA at www.americancraftspir its.org. Cheers!

AMERICAN DISTILLING INSTITUTE

California is the largest spirits market in the U.S., and is home to Gallo, the largest winemaker and one of the largest distilleries in the country. A few years ago, the California Artisanal Distillers Guild, in the effort to get basic business rights such as being able to sell tastings and bottles directly from a tasting room, got legislation passed that also defined a craft distiller as making fewer than 150,000 proof gallons per year.

This definition is now being used by dis tributors and retailers to create division between the large and small distilleries in California and in other states to retain the status quo and prevent direct-to-consumer (DTC) legislation. At the time of writing, it appears that CA SB620 will not be moving forward, which means that California will not have DTC shipping any time soon. This is a huge setback to the 229 distilleries in the state — and any distilleries who wish to sell to California consumers.

Much like the efforts to get the Federal Excise Tax reduction passed, we need to work with all distilleries and make sure they are in cluded, not excluded, from new legislation. We hope that we can work with state guilds and all distillers to get laws changed, in and out of state.

Changing topics, ADI 2022 Craft Spirit

Conference & Expo returns this year with a new look to reflect a modern, determined, and forward-looking industry. The 19th annual ADI Conference will be held at the Americas Center Convention Complex in St. Louis, Missouri, from September 14 to 16. With a renewed focus on education, ADI expects re cord attendance in 2022 of more than 1,900 attendees and 190+ sponsors and exhibitors. In addition to being the world’s largest gather ing of craft distillers and suppliers, the event is chock full of exciting first-ever features. The jam-packed agenda features over 50 top ic-specific breakout sessions and workshops, distillery tours, and tastings. Registration is now open at Distilling.com.

The St. Louis Conference kicks off on Wednesday, September 14, with an all-day Corn Whiskey Masterclass. This immersive workshop features a theoretical session, fol lowed by a visit to Wood Hat Distillery led by its founder Gary Hinegardner. We are also holding several other pre-convention work shops, including our first-ever financial work shop for distilleries.

Also on Wednesday the 14th is the Legislative Summit, hosted by DISCUS for the U.S. guilds. The Legislative Summit will focus on U.S. guild collaboration on legisla tive topics of interest and actionable items

CRAFT MALTSTERS GUILD

Craft maltsters are continuing to adjust to the ever-changing grain market issues driven by the conflict in Ukraine. Traditional market prices soared during the initial weeks of the war’s start and have remained volatile as win ter wheat harvest began in late May and early June. In an odd twist, these conditions have provided an opportunity to educate brewers

and distillers on the value of sourcing from more stable, local suppliers. Maltsters antici pate continued market disruption and higher overall prices throughout the remainder of 2022.

In May, the guild hosted the first in-person Advanced Class in Craft Malt Production since 2019! This course was developed

Rebecca L. Harris President, Head Distiller, Catoctin Creek Secretary, Board Member, STEPUP Foundation President, American Craft Spirits Association

for our industry’s state leaders. Wednesday’s events culminate with an evening open ing night tasting in collaboration with the Missouri Craft Distillers Guild at the Marriott St. Louis Grand, our headquarter hotel locat ed steps from the convention center.

On the morning of Thursday, September 15, the ADI Conference kicks off with a key note from Dr. Anne Brock, the Gin Guild’s Grand Rectifier and the much-celebrated master distiller at Bombay Sapphire. The evening of the 16th features a visit to the Gin World event at the St. Louis Grand, one of the world’s largest gin consumer events. The day after the 2022 Conference, September 17, ADI convenes the Gin Summit at the Marriott St. Louis Grand. Please see ADI’s monthly e-newsletter and Distilling.com for updates and registration details on all our events.

“The 2022 Conference promises to be our biggest ever,” said ADI President Erik Owens. “And it’s the perfect set-up for next year’s 20th anniversary conference, ADI 2023 Las Vegas!” For those who plan to attend the 2022 St. Louis ADI Conference, don’t miss any issues of ADI’s e-newsletters, which will feature famous travel and beverage reporter Virginia Miller’s reviews of the best bars and restaurants in “the Lou.”

Erik Owens President, American Distilling Institute

by Hannah Turner from Montana State University and Hugh Alexander, an experi enced maltster from Scotland. The course was designed to serve the needs of malthouses in planning as well as staff training for existing malthouses. Topics included engineering, safety, grain selection, and quality control. Students also received hands-on training on

14 WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM

OUR CRAFTED RECIPES AND CUSTOM MASH BILLS MAKE SURE YOU WON’T BLEND IN CONTACT US TO DISCUSS YOUR PROJECT TODAY SouthernDistilling.com + 704-978-7175 Custom Mash Bills + Guaranteed Consistency + Contract Distilling

germination testing and sensory evaluation. The course was hosted by Southern Illinois University at their beautiful new Fermentation Science Institute in Carbondale, Illinois. The next Advanced Class is slated for March 13-16, 2023, in Portland, Maine, and will precede our seventh annual Craft Malt Conference.

This fall, the guild will host the third annu al Craft Malt Week from September 11-17. Each year this event is designed to coincide with the Harvest Moon as a way to connect the craft beer and spirits lovers with the

agricultural roots of their chosen tipple. Malthouses, breweries, and distilleries are invited to plan tasting events, educational presentations, bottle releases, and collaborations to celebrate.

The guild will also host our sec ond annual Malt for Brewers & Distillers Workshop on September 19-20. This intensive two-day workshop will be hosted by the University of California Davis and will include lectures on sensory evalu ation, certificate of evaluation assessment, barley breeding efforts, and malt production.

Attendees will also tour the UC Davis Brewing Program’s pilot brew ery and fermentation science labs and visit Admiral Maltings in Alameda, California.

As we look to 2023, we hope to (finally) make it to Portland, Maine, for an in-person Craft Malt Conference. Please stay tuned to www.craft malting.com for more information on con firmed speakers and registration information.

Brent Manning Board President North American Craft Maltsters Guild

DISTILLED SPIRITS COUNCIL OF THE UNITED STATES

Happy 10-year anniversary to Artisan Spirit Magazine! We are proud to sponsor and celebrate such an incredible outlet that shares the creativity, innovation, and integrity of our industry!

Annual DISCUS Conference: Stronger Together

It was great to see many folks in the indus try at our annual conference in New Orleans this year. From the opening welcome fea turing a marching band with Lt. Governor Billy Nungesser (R), to the trade show and innovation showcase, to closing with a Spirits United parade right on Bourbon Street, we were thrilled to be together again. This year we celebrated the outstanding contri butions of the following exemplary leaders who have each, in their own way, support ed the growth of our great industry and the wider appreciation of our great products: DISCUS Lifetime Achievement Award, Dr. Joy Spence, Master Blender, Appleton Estate Jamaica; DISCUS Dave Pickerell Memorial Craft Member of the Year, Scott and Becky Harris, Owners Catoctin Creek Distillery; DISCUS Humanitarian/Service Award, Women of the Vine & Spirits Foundation (Deborah Brenner, President); and DISCUS Impact Award for Emerging Leaders, Nicole Austin, General Manager and Distiller, Cascade Hollow Distilling Co. This year’s

grand winner of the innovation showcase was SoMax Circular Solutions for their inno vative resource recovery technology, which uses hydrothermal carbonization and can help distilleries convert distilling byproducts, including spent grains, into renewable energy, eliminating disposal cost while also improv ing the environment.

DISCUS Launches New Industry Website and Foundation

The DISCUS team is excited to share the launch of two new initiatives to con nect and support the distilled spirits indus try: Destination Distillery™ and DISCUS Foundation.

DestinationDistillery.com is a new website providing a tourism-driven experience and educational journey into the cultural heritage and history of spirits in America. Visitors to the website will be able to explore many of America’s most famous distilleries as well as up-and-coming ones, state-by-state trails, the economic impact of the spirits industry by state, and important landmarks connected to the history of distilling and spirits in our country. By showcasing distillers large and small, Destination Distillery™ will serve as a unifier for our industry and will continue to drive tourism to local regions and further the economic contributions that all distillers make to their communities.

If you know a distill ery looking to partici pate, simply have them fill out the intake form to opt into the platform.

DISCUS Foundation, the association’s new 501(c)(3) charitable arm, was established to operate exclusively for charitable purposes in support of the betterment of the distilled spirits industry. Specifically, the DISCUS Foundation will support the sector by:

1) Providing education scholarships that support personal and business develop ment within the industry to bolster the growth of a diverse talent pipeline;

2) Increase awareness and adoption of industry sustainability best practices;

3) Increase opportunities and funding for diverse distilleries and promote diversi ty across all levels of employment across the industry;

4) Promote social responsibility and adver tising guidelines and best practices to educate consumers and businesses on responsible consumption; and

5) Support the industry’s continued growth in key U.S. and global markets.

Fill out Destination Distillery™ intake form

Learn more about Craft Malt Week

Learn more about the Malt for Brewers & Distillers Workshop

16 WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM

Where S cience Meets Ar t

Yeast, Nutrients, and Process Aids

At La l l e m a n d D ist i l l i n g, o u r si n g l e s o u rce p h i l o s o p hy p rovide s t h e hig h es t q u a l i t y i n g redi e nt s, t a i l o re d te c h n i c a l s e r v i ce a n d e d u c at i o n , a n d i n d u s t r y l e a di n g experi e n ce to s u p p o r t yo u r n ee d s. Yo u r spirit s a re o u r p a ss i o n , yo u r needs a re o u r m o t i vati o n .

Contac t us to learn more today.

w w w.lallemanddistilling.com

As the leading voice and advocate for dis tilled spirits in the United States, DISCUS is uniquely positioned to set the industry standard for giving back to our communities, rising leaders, and consumers. The DISCUS Foundation will serve as our industry’s stan dard-bearer when it comes to providing funds to support the betterment of our sec tor through nurturing our future workforce, enhancing sustainable practices, promoting diversity and supporting the growth of our great spirits industry. Financial donations to the DISCUS Foundation are tax-deductible and can be applied to a specific initiative or to the general fund.

Securing Wins in the States for the Spirits Industry in 2022

As the first half of 2022 wraps up, DISCUS’ efforts on the state level have resulted in sup plier savings of at least $176 million. This

includes: Defeating tax threats in four states (CO, HI, MS, NY); engaging on spirits-based ready-to-drink bills in 15 states including passing a tax reduction and retail access ex pansion in VT; securing studies in three states (ME, MD, WV); defeating a bill to limit con tainer sizes for spirits-based RTDs to receive a reduced tax rate in NE; passing permanent cocktails to-go (CTG) in two more states (DE and RI) bringing the total to 18; passing CTG extensions in another three states (ME, MA and VA) and adding a new temporary measure in New York bringing the total to 16; monitoring direct-to-consumer shipping in 15 states; engaging on bills in seven states and securing a study bill in Maine; passing or expanding distillery sales laws in Iowa, Minnesota, and New Hampshire; and gaining additional market access wins in 13 states.

Virtual Bar Helps Educate Distillery Visitors & Consumers

It’s easy to say “know your limits and stick to them” when it comes to drinking, but much harder to learn what your limits should be — that’s why we created the new and im proved Virtual Bar app. Our Virtual Bar is a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) calcula tor that uses the latest science to help folks get a better understanding of how different factors like food, age, gender, height, weight, alcohol content, and others affect their in dividual BAC. Just this summer we gave the Virtual Bar a fresh coat of paint and other en hancements to make it even easier and clearer for consumers to understand their limits and know what “drink responsibly” means for them. Find the Virtual Bar in the Apple App Store and Google Play stores, or at www.re sponsibility.org/virtualbar.

Chris R. Swonger President & CEO

AMERICAN STATE GUILDS

ARIZONA CRAFT PRODUCERS ASSOCIATION

The Arizona Craft Producers Association has spent the past decade laying legislative foundations and affecting changes to Arizona’s liquor laws creating an extremely favorable

climate for craft production of exceptional distilled spirits. This environment has prov en successful in international markets and competitions for our members, from winning numerous Best of Class, Best of Show, global top 10s, and icon awards. Arizona has moved to the forefront of American rum production

led by distilleries in Kingman and Elgin. Guild/Association lobby measures have cre ated a unique and positive relationship with wholesalers and retailers, and their lobbies, that don’t exist in most markets. This rela tionship allows for further advancement of our young Arizona industry.

Dr. Garrison Ellam, Ph.D. D.Sc. Arizona Craft Producers Association

CALIFORNIA

CALIFORNIA ARTISANAL DISTILLERS GUILD

I am writing this from the ACSA confer ence in New Orleans and looking back to my first industry meeting at ADI in Louisville, Kentucky 2012. So much has changed, and yet many things have stayed the same. The California Artisanal Distillers Guild was

formed in 2012 and immediately went to work on legislation. We met with Senator Nancy Skinner and wrote AB #933 which gained us the privilege to pour tastings, ¼ ounce with a maximum of six per person/per day. Then the focus was bigger and AB #1295 was written in 2014 and became known as the California Craft Distillers Act.

CADG has had to raise money, find

members, and elect board of directors all while remaining a 100 percent volunteer or ganization. We have paid for top-flight rep resentation with Nossaman LLC, Richard Harris was our representative and passed the torch this year to Nate Solov. There have been a number of smaller “wins” alongside those two big bills as well. But, nothing prepared CADG for the storm that became SB #620.

Distilled Spirits Council of the United States and Responsibility.org

ARIZONA

18 WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM

During COVID-19, California came to a grinding halt and tasting rooms became stag ing areas for hand sanitizer orders. Distillery life became more of a fight to survive, while also helping the public deal with a global pan demic. It was during this time our work with ABC paid off and we were offered a chance to work on some relief efforts aimed at helping us stay in business. We gained DTC shipping on an emergency basis, and many distillers found a new way to keep customers involved and in touch with their businesses. Those sales kept the lights on, overhead paid, and employees on the payroll. Unfortunately, that temporary status came to an end on March 31, 2022. Our customers are slowly coming back, but giving up DTC shipping was much tougher than anticipated. A combination loss of revenue and disappointing the customers with “I’m sorry we can no longer ship to you” made the summer of 2022 a rough one. That brings us to SB #620 that held so much hope for small distillers in California.

The bill was the result of nearly two years of negotiations with every interested party we could think of. The original bill was as inclu sive as possible, and was greeted by the spirits industry as a “best case”. Unfortunately, the

senate governmental organization commit tee was not as welcoming, and immediately pulled out the trimming scissors. Gone were distillers producing more than 150,000 gal lons a year and alliances questioned. CADG was told the senate is only going to allow small distillers (Type 74) to ship DTC, no type 4, type 7 and nobody over that production cap. Our decision was to take it and live to fight another day, or turn our back on the authors and everyone loses. That decision was clear, we had to support the bill that helped the vast overwhelming number of our members.

This new language was to be heard by the assembly G.O. committee in June, but that was not allowed to happen. Forces not orig inally considered came forward to voice op position, even though the bill did not affect their membership in any way. The Wine Institute was concerned that accepting limits may be seen as the new direction DTC ship ping could go and wine’s unlimited shipping harmed. ACSA and the distributors stayed and supported CADG while other industry groups did not; ultimately the bill was pulled from being heard and died.

Now we are back to square one and a very important lesson has been learned. Industry

unity, joining trade associations, being in volved and doing the hard work is vital. We can’t just make whiskey, vodka, or gin and ex pect our business environment to get better. Hard work, money, and time are needed to gain what’s needed. For 10 years CADG and other state guilds have worked with ACSA to make the distillers' business environment bet ter. It takes volunteers who step up and work together on these legislative efforts and raise money to pay the bills.

CADG has experienced so much over the years, and the number of licensees shows the result of that work. Our first meeting had seven attendees, we now have over 50 mem bers. The new type 74 license now accounts for 169 DSPs out of a total of 191, more than all other license types. That explosion has truly made CADG a statewide association with a wide variety of products. The original pioneers St. George Spirits, Charbay Spirits, and Germain-Robin opened up this industry in 1982. The job over the next 10 years is to bring unity, a singular voice, and dedication to local, state and national issues affecting the distilling industry. It is a very big job, but somebody has to do it.

Cris Steller Executive Director, California Artisanal Distillers Guild

SAN DIEGO DISTILLERS GUILD

We recently added three more festivals to our annual activities. North County, East County, and South County, in addition to our main Distiller's Guild Festival on August 27

at the Lane in Downtown San Diego. We will also be offering a "consumer" level mem bership for $250 per year that will include a t-shirt, custom Glencairn tasting glass, and inclusion to all four festivals. Some distilleries

will be offering perks at their tasting rooms (10 percent off, special releases, member events, etc.) too.

THE DISTILLERS OF SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY

The beverage and tourism industry in San Luis Obispo County continues to grow. The Distillers of SLO County increased its mem bership to 14 distilleries this year. Our mem ber distilleries are churning out a wide variety of innovative spirits, including whiskey, bran dy, rum, gin, vodka, and liqueurs. We enjoyed welcoming our community and its visitors

to our third annual Distillery Trail Weekend from August 12-14. During Trail weekend, each distillery was able to showcase their ar tisan spirits as well as unique experiences like craft cocktails, food pairings, music, distillery tours, and more. For the first time, the growth of our organization has warranted the expan sion of our executive team: Lynette Sonne has been hired as our executive director.

Aaron Bergh

President & Distiller, Calwise Spirits Co.

Founder & Distiller, Old Harbor Distilling Co.

THE DISTILLERS OF SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY OFFICERS

PRESIDENT

Aaron Bergh, Calwise Spirits Co.

VICE PRESIDENT

Monica Villicana, Re:Find Distillery

TREASURER

Lola Glosner, Pendray’s Distillery

SECRETARY

Max Udsen, Bethel Rd. Distillery

Michael Skubic

20 WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM

COLORADO

COLORADO DISTILLERS GUILD

It has been a busy spring and summer for the Colorado Distillers Guild. Outside of our legislative agenda (outlined below), we have been diligently working on re-launching the Colorado Spirits Trail. The trail will now live in an app which can be downloaded onto your Apple or Android devices. The trail in cludes all of our guild members with tasting rooms and will serve as a platform for tourism to our distilleries once again!

During the 2022 Colorado Legislative Session, which finished-up a few weeks ago, the Colorado Distillers Guild was forced to fight a defensive battle against multiple threats. These included:

I. A BILL THAT WOULD HAVE APPLIED A “SIN TAX” ON ALL ALCOHOL, TOBACCO, AND OPIOID MANUFACTURERS AND DISTRIBUTORS IN COLORADO.

Without going into a lot of detail, we and the other affected constituencies were able to work together to keep this bill from ever being formally drafted and sent forward. The concern, however, is that it will likely be pro posed again next year.

II. HOUSE BILL 22-1355

The Producer Responsibility Program for State-Wide Recycling. This bill requires all industries that use any sort of packaging to pay fees (essentially another excise tax, based upon production volume) into a fund to cre ate a non-governmental agency to pay for recycling in Colorado. This agency under the proposed legislation would have had no over sight, and very broad powers to fine produc ers and “remove products from the Colorado market,”

This bill is backed by can manufacturer Ball Industries and Coca-Cola (a major owner of recycling centers in Colorado). It is essential ly a green-washing of the recycling and alu minum can industry’s business development efforts in an attempt to force Colorado’s man ufacturers to pay for recycling services that the bill’s underwriters would provide.

We and others worked hard to defeat this bill unsuccessfully, as it could cause significant harm to Colorado’s distillers. We were able to get changes made to the bill that was signed

into law that made much of the bill a “study,” and required oversight of the new nonprofit’s operations. We were also able to get language put into the bill excluding smaller businesses (including the majority of Colorado’s distill ers). Regardless, this issue will remain prob lematic for all manufactures and food produc ers of any sort in Colorado and will need to be revisited in the near future.

III. HOUSE BILL 22-1417

Alcohol Beverages Task Force and Retail License. This bill was a cobbled-together piece of proposed legislation that included both a task force to rewrite Colorado’s liquor laws and a liquor compromise that would have un done the prior liquor compromise Colorado’s liquor constituencies worked so hard to put in place several years ago. Most notably, this would have eliminated the “Liquor-Licensed Drug Store” license that allows grocery stores to bring in spirits over time, while delaying wine in grocery stores for a few years.

The latter half of this piece of draft legisla tion was an attempt by certain members of the alcohol constituency here in Colorado to delay big-grocery’s proposed upcoming bal lot issues that will bring wine into all grocery stores, and allow for third-party delivery of beer and wine.

The first half of this piece of draft legislation was to create, by statute, a task force to spend the next two years rewriting and renegotiat ing all of Colorado’s liquor laws. This piece of the bill was strongly backed by Governor Polis. The structure is something that was largely considered as unconstitutional by many. Further, it proposed that the distilled spirits industry would have only one member on this task force to represent all manufactur ers, both here in Colorado and elsewhere.

There were lots of problems that would have caused harm to Colorado’s distilleries in both parts of this piece of legislation. Fortunately, so many people opposed part or all of this legislation that it was killed in committee.

IV. FORMATION OF THE COLORADO LIQUOR ENFORCEMENT DIVISION’S 2022 ADVISORY GROUP

In the aftermath of the failure of HB221417 to make it out of committee, Governor

Polis’ office has called for the formation of an advisory group to look at rewriting Colorado’s Liquor Laws (essentially the same task force that HB22-1417 would have created).

While this effort will move forward, the Colorado Distillers Guild was successful in both making sure that there are two represen tatives from our industry in the group — one representing “local” manufacturers and one representing “large” manufacturers — and that one of those two be a Colorado Distillers Guild representative.

Since this effort is no longer in statute as it was originally proposed, it means that the next couple of years’ legislative sessions will be heavily dominated by additional liquor is sues coming out of the group’s recommenda tions forcing the Colorado Distillers Guild to continue to be on the defensive.

V. ALCOHOL BALLOT ISSUES

The grocery industry has proposed multi ple ballot issues to ultimately bring wine into all grocery stores and to allow beer and wine products to be delivered directly to consum ers by third-party providers. While the most broad-reaching of these ballot issues has re cently been struck down by the Colorado Supreme Court, Ballot Initiative 121 (wine in grocery) and 122 (third-party delivery) will ultimately move forward. Given the polling, Coloradoans will likely vote to approve both next year, giving the beer and wine catego ries much greater market access then spirits, and threatening the future of the majority of Colorado’s liquor stores.

In response the Colorado Distillers Guild will need to work with the other alcohol con stituencies and the legislature next session to work out some sort of parity deal if possible. That may be an uphill fight.

In conclusion, the current legislative and regulatory environment in Colorado is rap idly changing, posing significant threats to Colorado’s distillers. As such, rather than being able to work on issues such as directto-consumer shipping and other things to help our businesses, the Colorado Distillers Guild will need to continue to focus most of our efforts on defense in our legislative and government affairs activities for the next cou ple of years.

22 WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM

Lastly, it should be noted that throughout this past legislative session the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (DISCUS) has been incredibly supportive and cooperative with the Colorado Distillers Guild. This is

largely due to both their CEO’s increased sup port of craft producers and their new regional Government Affairs Director, Kristi Brown. While the Colorado Distillers Guild and DISCUS won’t always have common ground

or interests, many of these current issues are areas where we do share common purpose and their additional “reach” will continue to be incredibly valuable to us.

Stephen A. Gould Golden Moon Distillery Board Member for Government Affairs, Colorado Distillers Guild

CONNECTICUT

CONNECTICUT SPIRITS GUILD

Congratulations on 10 years!

In the same ten year span, the Connecticut craft spirits industry began to catch steam and has grown as well. One of the oldest craft dis tilleries in the US, Westford Hills Distillery, is our oldest here in Connecticut and it and about 15 others and thriving today within the small Connecticut footprint. We have

award-winning and unique distilleries in all four corners and the center of our state with more in the pipeline. In 2016, we founded the Connecticut Spirits Trail and started out with 10 distilleries. Through the ensuing years, we have accomplished with the state legislature a lot for the state's distillery industry including being able to sell bottles in our tasting rooms, offering visitor tours and tastes, local deliv ery and shipping of bottles and cocktails to go, the ability to operate a Connecticut craft

cafe or full restaurant, and the ability to sell bottles at festival events. Of course, we are al ways looking to formulate changes to the law, whether it be to encourage more favorable taxation, overall business environment fac tors, and marketing/sales opportunities.

We truly appreciate everything you have done for our industry including allowing us to contribute to this space in your wonderful publication. Cheers to a great ten years and to many, many more!

Tom Dubay

Co-founder, Hartford Flavor Company President, Connecticut Spirits Trail

FLORIDA

FLORIDA CRAFT SPIRITS ASSOCIATION

The Florida Craft Spirits Association (FCSA) officially ramped up in 2020, and we hit the ground running! FCSA hosted the first Sunshine Spirits Festival in Tampa in the Fall of 2021 where almost 30 Florida distilleries showcased their hard work and unique flavors to hundreds of attendees. The second annu al Sunshine Spirits Festival is taking place Oct. 15, 2022, in Jacksonville, and we are

thrilled to announce that the FCSA will be releasing the Florida Bastard, a blended whiskey using distillate from our member distilleries at this year’s festival. As far as we know, this is the first time a blended whiskey has been released exclusively from multiple Florida distilleries made of only Florida dis tillate. The Florida Bastard will be a limited release available only at the Sunshine Spirits Festival, and all proceeds from sales will go back to the FCSA.

Also, this past April we officially launched

the Florida Distillery Trail, to lead adventur ers on a journey through the Sunshine State to discover the flavors and cultures that make up Florida’s vibrant landscape. Our member distilleries have given out more than 10,000 maps to date, and we've seen incredible par ticipation among spirits enthusiasts. The trail map can also be found on our website with more distilleries to be added in the future. Email floridacraftspiritsassoaciation@gmail. com for more information.

David C. Cohen

President & Head Distiller, Manifest Distilling President, Florida Craft Spirits Association

ILLINOIS

ILLINOIS CRAFT DISTILLERS ASSOCIATION

The Illinois Craft Distillers Association (ICDA), a membership organization consist ing of and advancing the interests of indepen dent craft distillers in the state of Illinois, with associate membership for industry suppliers, voted to elect two new members to the Board of Directors ahead of the 2022 term. The

ICDA board of directors then elected officers.

The ICDA held its first in-person member meeting of the year on April 6, with the main topic of discussion being the guild’s legisla tive agenda for the year. Following success ful efforts to update craft distillers’ license classes to achieve greater parity with other beverage alcohol sectors in the state in 2019, the guild’s membership identified Direct to Consumer Shipping (DTC) as its principal priority for Illinois’s next legislative session.

ILLINOIS CRAFT DISTILLERS ASSOCIATION OFFICERS

PRESIDENT

Ari Klafter, Thornton Distilling Company

VICE PRESIDENT

Nick Nagle, Whiskey Acres

TREASURER

Jordan Tepper, Apologue Liqueurs

SECRETARY

Andy Faris, JK Williams Distilling

24 WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM

Representatives from the Ship My Spirits campaign attended this meeting to update the guild on their DTC efforts in New York and elsewhere.

To help guide and streamline our DTC

efforts, the ICDA Board has been in touch with DISCUS, the ACSA’s DTC committee, the Kentucky Distillers Association, and oth er key stakeholders. The ICDA would like to invite leaders of any state guild that is finding

success in DTC-shipping legislation to reach out to discuss lessons learned and potential ways to partner. Please reach out to Ari at President@IllinoisDistillers.org to connect.

Ari Klafter

President, Illinois Craft Distillers Association Head Distiller, Thornton Distilling Company

MAINE

MAINE DISTILLER’S GUILD

On December 2, 2014, a group of eight Maine distillers met at Sweetgrass Farm Winery & Distillery in Union, Maine, to form the Maine Distiller’s Guild (MeDG) with the purpose of joining together to focus on mar keting, legislative actions, and other indus try needs for Maine distilleries. Now seven and a half years later, the number of Maine distilleries has grown to 20 and so have the accomplishments. Also in 2016, the MeDG launched www.MaineDistillersGuild.org website to showcase the unique and varied members of the guild from across the state. Included in this website is an interactive map of distillery locations, information, and driv ing directions. Additionally, MeDG focused on legislative actions through work with BABLO, Maine Liquor Control, as one voice in regulation and legislation to accommodate changes to improve business for craft distill ing in the state of Maine and saw the passage of key legislation that eased onerous product transportation rules for distilleries.

In 2017 the MeDG focused on building relationships with national craft spirit groups, other Maine beverage guilds, state liquor control, the bar associations, restaurateurs, and spirit marketing groups with its target of developing a Maine spirit event. The MeDG partnered with Maine Spirits, the exclusive

wholesale distributor for spirits in the state of Maine. Maine-made spirits and distilleries now have a dedicated section on their website, www.mainespirits.com. With Maine Spirits’ assistance the MeDG rolled out a campaign to consumers, bars, and restaurants to choose locally made spirits. The slogan “Make Mine from Maine” is now ubiquitous throughout the state.

In 2018, the MeDG worked on marketing efforts to showcase member spirits at events in Maine. The first was a partnership with Portland’s spectacular food and drink celebra tion called Harvest on the Harbor, harveston theharbor.com. This event showcases locally made spirits in cocktails paired with Mainesourced foods. The second was the MeDG joining the Maine Harvest Festival, which celebrates the bounty from farms across the state, www.maineharvestfestival.com. These events are ongoing each year and the MeDG is proud to be involved.

The MeDG’s major focus for 2019 was on needed legislation. MeDG partnered with the food and beverage division of the Bernstein Shur lobbying firm with efforts centered around three bills, the most im portant of which lowered the fee the state charges for products sold in our own tast ing rooms.

The year 2020 found the members of MeDG focusing on implications of the pandemic with our individual businesses.

Maine distilleries retooled to produce hand sanitizer, increased their wholesale business, found creative and safe ways to welcome visi tors on our premises, and took the opportuni ty to create new products. Then 2021 forced us to adjust to the rapidly changing circum stances of the pandemic, which interrupted our supply chains and employees.

This year, 2022, the MeDG will be coming back together to meet as a group, reassess our needs, and look to other states for guidance and perspective with new legislation and lobbying efforts that ease the burden on dis tilleries. The guild will continue to draft legis lation following the examples of other states that enjoy a more favorable business climate for distilleries. MeDG congratulates Artisan Spirit Magazine on its 10-year anniversary, gives thanks to all its support of state guilds and the growing distilling industry, and wish es Artisan Spirit continued success.

MAINE DISTILLER’S GUILD OFFICERS

PRESIDENT

Ned Wight, New England Distillery Company

VICE PRESIDENT

Jordan Milne, Hardshore Distilling Company

TREASURER

Jeff Johnson, Stroudwater Distillery

SECRETARY

Keith Bodine, Sweetgrass Farm Winery & Distillery

Constance A. Bodine Sweetgrass Farm Winery & Distillery

MINNESOTA

MINNESOTA DISTILLERS GUILD

As far as the legislative session, we are so excited for the omnibus liquor bill that was passed in Minnesota. We can now sell

one 750mL per person per day or up to two 375mLs per person per day. This will help so many of our distilleries that want to get their brand to the customers that are traveling to their distilleries and tasting rooms.

We had amazing support from so many of

our legislators and senators who got this bill across the finish line. We also had an incredi ble lobbyist who helped us along the way, and we couldn't have done it without the amazing Minnesota guild legislative committee.

As far as what's happening in the industry

26 WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM

We’re a branding and design agency built to show brave brands a way forward. We deliver strategy, storytelling and package designs that move products off shelves as fast as they’re stocked.

creaturetheory.com The soul is in the details.

See more examples of our branding and label design work

Photography: Andrew Welch

See more examples of our branding and label design work

Photography: Andrew Welch

here in Minnesota we are focused on working hard together now that everything is opening up. We're also highlighting all of the distilleries

using local grain fruit and botanicals. This will be our third year at the Minnesota State Fair, so a huge shout out to our president Mark

Schiller, and our state fair team that makes it happen every year.

Gina Holman

J. Carver Distillery, Founding Partner American Craft Spirits, VP Minnesota Distillers Guild, VP Minnesota Distillers Guild, Legislative Chair

MISSOURI

MISSOURI CRAFT DISTILLERS GUILD

The Missouri Craft Distillers Guild, found ed by five distilleries in 2018, is 39 members strong four years later. In March 2022, mem bers from 26 distilleries attended the annual meeting in Kansas City, hosted by Restless Spirits, J. Rieger & Co., and Tom’s Town Distilling Co. Industry ally members, and representatives from the Missouri Division of Alcohol and Tobacco Control and DISCUS attended as well. Elections were held, and the current board of directors responsible for promoting and advocating for Missouri’s growing craft distilling industry are listed to the right.

MCDG is ready to publish its third annu al Missouri Spirits Expedition brochure, an

MISSOURI CRAFT DISTILLERS GUILD BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Lynn DeLean-Weber, PRESIDENT Edelbrand Pure Distilling, Marthasville

Ryan Maybe, VICE PRESIDENT J. Rieger & Co., Kansas City

Sarah Miller, TREASURER & FINANCE COMMITTEE CHAIR Switchgrass Spirits, St. Louis

Tara Steffens, SECRETARY

Pinckney Bend Distillery, New Haven

Keith Hock, MEMBERSHIP & EDUCATION COMMITTEE CHAIR

Copper Run Distillery, Branson West

Van Hawxby, LEGISLATIVE COMMITTEE CHAIR DogMaster Distillery, Columbia

Brandon Eckardt, MARKETING COMMITTEE CHAIR Naked Spirits, Brentwood

experience that takes visitors across Missouri to meet its family-owned distillery mem bers and explore the spirits they love creating. Coming up in September, the 2022 ADI Conference is being held in St. Louis for the very first time. MCDG members will host the Welcome Tasting as part of the kickoff and unveil its new branding: Missouri –The Heart of American Craft Spirits. We are indeed excited to have our distillers gath er together to shine a bright spotlight on the vibrant craft distilling scene in our state.

Lynn DeLean-Weber President, Missouri Craft Distillers Guild Edelbrand Pure Distilling, Marthasville

NEW YORK

NEW YORK STATE DISTILLERS GUILD

The New York State Distillers Guild notched a significant public policy win this summer with the passage of a bill that creates parity within the craft beverage community by extending tasting room privileges to all distiller license classes. Before the passage of this bill, only products produced with New York agricultural products could be offered for sale in tasting rooms. This means a dis tillery that, for example, produces rum or gin made from out-of-state GNS can for the first time taste and sell on- and off-premise any spirit they produce.

The new law also reduces monthly price

posting requirements to annually. This signif icant win has been a priority for the guild for the past six years.

This fall the guild will build on this legis lative victory with a renewed push for di rect-to-consumer shipping. Like many states, during the pandemic New York allowed DTC shipping, which was a huge benefit to craft distilleries and demonstrated that other sales channels were not impacted by DTC ship ping. Since those privileges were rescinded, we have been working to enact permanent DTC in New York. This effort will include a coordinated effort by our members to turn our consumers into advocates for legislative change, as well as support from our national partners at ACSA and DISCUS.

The guild will also continue to press for equal tax treatment with other beverage manufacturing classes under the Alcoholic Beverage Production Credit.

On the marketing side, the guild is wrap ping up a year-long effort to help all our mem bers tap into guild online resources including listings on NYDistilled.com and guild social media channels (@nydistilled).

The guild is proud of its roughly 100-dis tillery membership representing the whole state and a wide range of world-class distilled spirits. Our distilleries are in cities, small towns, and rural areas. Please contact us at NewYorkStateDistillersGuild@gmail.com if you would like to join our community as a distiller or as a sponsor.

Teresa Casey Executive Director, New York State Distillers Guild

28 WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM

NORTH CAROLINA

DISTILLERS ASSOCIATION OF NORTH CAROLINA

The Distillers Association of North Carolina congratulates Artisan Spirit Magazine for its 10th anniversary celebra tion! Cultivated Cocktails, my family’s distill ery, is also celebrating our 10th anniversary in business in 2022. Our longevity in the distill ing industry and overall success occurred be cause DANC’s advocacy for North Carolina’s craft distilling industry significantly improved business conditions for distilleries.

When we started our family business in 2012, North Carolina state law allowed dis tilleries to manufacture spirits and sell our products at wholesale to local ABC Boards and exporters in North Carolina. We could offer visitors free tastings of our products, but

they could not purchase our products direct ly. We had to send them to a local ABC store to buy our spirits. Despite these limitations, my family still opened a distillery!

Fast forward to 2022. We have expanded our business to two locations that include our production distillery and a tasting room/dis tillery that serves most of our visitors. At our tasting room, consumers can learn about our distilling process and receive a free tasting. As a result of DANC’s hard work advocating for our industry, consumers can now purchase our spirits directly from us with no bottle lim itations and on Sundays and holidays when ABC stores are closed. They can try our prod ucts in a cocktail, in our lounge, and learn how to create cocktails with our products at home. We can offer free consumer tastings at special events outside our distillery and ABC

stores which allow us to introduce our prod ucts to consumers who do not have an op portunity to visit our distillery. We can ship our products directly to consumers in other states where permitted by law (not in North Carolina). The legislature recently authorized distilleries to receive a mixed beverage cater ing permit which means we now can serve our spirits at catered events.

DANC’s advocacy for improving business conditions and reducing unnecessary regula tions is why North Carolina’s craft distilling industry continues to grow. By the end of 2022, North Carolina will have over 100 dis tilleries operating across the state. To support that growth, DANC is looking forward to the next 10 years and will focus on promoting our industry and advocating for improving busi ness conditions.

SOUTH CAROLINA

SOUTH CAROLINA CRAFT DISTILLERS GUILD

The South Carolina Craft Distillers Guild (SCCDG) is pleased to announce that it was able to provide its members with a massive legislative win during last year’s legislative ses sion (January 2021-May 2021). This victory allows South Carolina’s distilleries to include a restaurant, separated from the production side, which can serve unlimited quantities of its own product for on-site consumption and increased the number of bottles distilleries could sell directly to a consumer from three to six 750 mL bottles. In addition, the restau rant can serve food and other alcoholic prod ucts via a wholesaler. This win was possible due to the SCCDG engaging with

Sweatman Strategies Government Affairs, which led the guild in 2021 at the state house in successfully passing this legislation. The bill passed with bipartisan support on May 4 and became law when South Carolina Governor Henry McMaster signed it into law on May 17, 2021.

The guild decided to immediately build upon its victory by also retaining Sweatman Strategies for its association management. In six short months, the guild has accelerated membership growth, activity and participa tion with well-attended quarterly member ship meetings and a legislative reception. In addition, the SCCDG made significant updates to its website, and with all the re cent achievements and activity,

the Guild has also attracted affiliate members.

The South Carolina Craft Distillers Guild is excited to announce that it will be hosting its first ever trade show at our fourth quarter, full membership meeting on November 10, 2022, from 1 p.m. to 7 p.m. at High Wire Distilling in Charleston, South Carolina.

Learn more about SCCDG's upcoming event

Scott Blackwell President, South Carolina Craft Distillers Guild

Leah Howard

President, Distillers Association of North Carolina, CEO, Cultivated Cocktails

IS YOUR GUILD OR ASSOCIATION MISSING? Don’t miss out on this opportunity to reach a national audience of distillers and suppliers! Share your latest victories, recruit supporters, request suggestions to solve your latest challenges, and inspire fellow groups. EMAIL BRIAN@ARTISANSPIRITMAG.COM TO GET INVOLVED!

30 WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM

BOOTSTRAPPING YOUR BRAND

WHAT YOU REALLY NEED TO HAVE FOR LAUNCH

With so many moving parts leading up to launching a new brand, it’s easy to get overwhelmed by next steps, logistics, and costs.

The road to launching a new brand is like riding a train: When everything is on track and run ning smoothly, your destination greets you with seamless speed and agility. When the train goes off the track or gets delayed, your journey can turn into a long and laborious trek, and in the worst cases result in absolute catastrophe.

BOOTSTRAPPING TIPS: THREE KEY BRANDING ELEMENTS

1 LOGO & PACKAGING

If your brand is the moving train, its packaging is the ticket. The logo and package are the first entry point into your world for the consumer. The way a package looks not only invites consumers to try your product, but it also reinforces its quality during consumption and assists with recall when your consumer wants to repurchase. Alcoholic beverage experts can act as a conductor and take a holistic ap proach to your launch while also getting granular; strategically realizing your vision while ensuring your precious time and money is never wasted on work you don’t like, and always adhering to regulatory standards.

2 WEBSITE

Eventually, you’ll want a fully built-out website that illustrates your brand’s story as well as your various offerings while allowing for quick purchases. But when you’re bootstrapping your launch, you at least need a landing page with contact information and a field for email list signups. While you can work with branding experts to de velop your initial landing page, you can easily create your own using WordPress, SquareSpace, Wix, and other DIY platforms. I recommend WordPress — it is a free, opensource content management sys tem that can easily allow your web site to grow as your needs increase, though it will take a bit more web site development knowledge to build on than would be required with a platform like SquareSpace.

BRAND BUZZ WRITTEN BY DAVID SCHUEMANN

WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM 33

SOCIAL MEDIA

Every train needs passengers, and social media is a help ful tool to invite people along for the ride. Even before your brand launches, gaining traction with your target audience through photos and videos of your products and the peo ple behind them lets users get to know you and your brand well before their first sip. If you don’t have those yet, shar ing the development process can capture the soul of your brand and provide a fun inside look for users. You can also work with a branding firm to develop social media post templates for an overall ‘vibe’ that you can use to create a cohesive look — this can be done relatively inexpensively.

You’ve poured your soul into your brand, and its launch isn’t the end of your journey — it’s only the beginning. We can’t stress this enough — it’s never too early to start planning. Setting yourself up for success by having an organized, realistic plan for what you can manage on your own, and what you’d rather have a team help you with will help keep your train on its track. Choose strategic partners to help you set a clear road map, establish clear budgets, realistic timelines, and connect you to strong vendor partners you can trust. These will all be key in making your bootstrapped brand a huge success. All aboard!

David Schuemann is the owner and creative director of CF Napa Brand Design. For more information, visit www.cfnapa.com or call (707) 265-1891.

3

1 8 6 25 6 2 7 0 0 + 9 0 + V I S I T M O O N S H I N E U N I V E R S I T Y . C O M 34 WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM

Non-GN, AMBA approved barley variety, assuring low levels of Ethyl Carbamate Predominant barley used to make single malt Scotch Sweet & bready, with notes of honey Available in whole kernel and flour Learn more about this whiskey malt at BrewingWithBriess.com/Odyssey ©2022 Briess Industries, Inc.

WHEN GLASS IS A TASTE EXPERIENCE. BY YOUR SIDE, SINCE 1994. Vetroelite Inc T: +1 646 559 0674 T: +1 (518) 984 3178 www.vetroelite.com ORIGIN LINES - VETROELITE ∧ SELF PROMOTION

S

ulfur compounds are of particular con cern in neutral spirits (e.g. vodka) as they can be detected easily because of the lack of other aromatic compounds usually found in gin and barrel aged spirits. In the distilling industry, there are many organic sulfurous compounds that can contribute to sensory faults. The three compounds that receive the most attention are the dimethyl sulfides, namely dimethyl sulfide (DMS) and dimethyl disulfide (DMDS), and meth yl mercaptan (MeSH). These compounds have low sensory thresholds, which means that their presence, even in low concentra tions, can have significant impacts. The sen sory thresholds for these compounds have been measured in wine and are 25 parts per billion (ppb), 29 ppb, and 3.1 ppb respective ly.1 It can be reasonably assumed that these threshold values would be even lower in a neutral spirit. Methyl thioacetate (MTA), a common compound created during fermen tation,2 is a thioester formed from acetic acid and methyl mercaptan, which has a sensory threshold of 50 ppb in wine.1 This compound is much harder to detect compared to the aforementioned compound. However, the problem arises when MTA naturally breaks down via a reduction reaction (Figure 1) into MeSH over time in a bottle of finished spirit.

This phenomenon has been studied in wine, which showed “[MTA] contributed signifi cantly to free MeSH concentrations in the wines post-bottling.”3

This is an order of magnitude shift in the sensory threshold limit. MeSH is a strong nucleophile, which often is oxidized to yield DMDS. Clean spirit that was put into the bottle would, over time, turn into a spirit no consumer would want. This is the issue that was discovered in the first few batches of vod ka produced at the distillery.

FIGURE 1: Reaction pathway of methionine to MeSH, MTA, and DMDS.

FIGURE 1: Reaction pathway of methionine to MeSH, MTA, and DMDS.

In the distilling industry, there are many organic sulfurous compounds that can contribute to sensory faults.

GOOD GUY DISTILLERS WRITTEN BY DAVID LETTENEY METHYL THIOACETATE GENERATION AND CONTROL IN DISTILLATION PROCESSES THE SCIENCE OF SULFUR Methyl Thioacetate Methyl Mercaptan DMDS Methionine H2S Reduction Oxidation Oxidation Reduction + Acetic Acid

WWW. ARTISANSPIRITMAG .COM 37