12 minute read

BALK AN RIDE

On an early morning in August 2013, we lined up with our bikes in a sun-drenched street in Budapest. Few of us had spent time together on a bike before, some had never even met before. And until that morning one of us had never even ridden more than 60km.

But there we stood, with nearly 1700km of riding ahead of us, and little more than a week to do it.

Thirteen different characters, unified by a love of cycling and the will to cross the Balkans on fixed gear bikes. Through Hungary, Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece and finally Istanbul and Turkey, right up to the border of our continent.

It all began in 2012 with a ride from Munich to lake Bodensee, to meet some friends from Stuttgart and circle the lake on a sunny weekend. Surprisingly, three guys from Hamburg had mixed with them and after two days of riding and having fun we felt that 300 kilometers was not enough. In the end, we rode more than a thousand; from Milan to Barcelona, fixed, with racks and panniers, sleeping on beaches and traffic islands. After that, everybody knew that this was just the beginning.

We started with a beautiful ride alongside the river Donau. Half of us were riding brakeless, which led to some exciting moments when sudden obstacles appeared, such as stray dogs bursting out of the undergrowth. Just as we were getting used to the dogs and making headway, a deep pothole destroyed all vague dreams of a perfect day one - skidding, a leg in the air, a sudden crash. The front rider had forgotten to warn the rest. Clenched teeth; a wounded hand barely out of plaster. We nursed our injuries with a long soak in the warm waters of the river Donau later that night. Our first night’s shelter was the backyard of A Müheli’s, a lovely bike shop in Szeged. That first night under the stars we made contact with the most aggressive mosquito species known to man, highly skilled in precisely spotting any non-protected millimeter of bare skin, and impervious to the several layers of absolutely useless expensive mosquito repellent. Within minutes we had been all but drained of blood.

All we’d learned about cycling in Serbia so far was that Belgrade’s cycling clubs stage their championships indoors on rollers because it is too dangerous to attempt them outside. Promising.

On our way to Belgrade we somehow split into two groups and lost each other. Now, a rule we’d set at the beginning of the tour raphaelkrome.com / zeitrapha.tumblr.com

Few of us had spent time together on a bike before, some had never even met before.

And until that morning one of us had never even ridden more than 60km.

(because it had worked on our 2012 excursions) proved to be wise: follow the route, no matter what! That might not sound too adventurous, but considering our route was devised on Google maps by connecting scenically promising stages and exciting cities while roughly avoiding big highways, believe me: it is.

A fully lit up football field in the middle of nowhere was the stage for our sudden and unexpected reunion. The group that had ridden ahead had been forced to a standstill by punctures. Without a pump between them, they had enjoyed a long walk to the football field. Just a few kilometers later we were given the chance to celebrate that unexpected reunion – a crazy Serb waved a bottle of Jack Daniels out of a little café on the darkened village road and shouted: “Come on! Drink with us!” – and sure we took that chance.

Barely fifteen minutes and half a dozen ‘one more, why nots’ later, some of us were doing joyrides in the crazy Serb’s car. We were wasted. Breaking loose was hard and some Serbs followed us, long after we’d left the village behind, doing wheelies on their superbikes.

50 kilometers later and a little closer to sober again we entered Belgrade, followed the biggest neon ‘hotel’ sign we could see and before anyone could even express his feelings on the idea, we found ourselves in fully Bang & Olufsen-equipped luxury apartments with rainforest showers, eating falafel on our expansive balconies.

The kind hotel owner loved the story of our journey to Belgrade and gave us some really special rates. The next day came as they always do, and we had to leave amazing Serbia and the crazy Serbs.

We met the first Bulgarian hills, leading to some intense tunnel rides - the local lorry drivers have their very own definition of safety-clearance.

Escaping onto a parallel cobbled road led us directly into a Roma ghost village with a big factory ruin.

Spotting an American flag on its roof, we approached curiously, coming to a sudden stop when we met a Spanish-speaking military guy who advised us to turn around NOW and immediately leave the area. Welcome to no-mans-land.

For the first time during our trip we could feel vibes of depression in the villages we passed. Everything was rather shuttered, compared to Serbia or Hungary. It was hard to believe that Bulgaria is a member of the European Union. The monstrous apartment blocks of Sofia, with junkyards in between functioning as playgrounds underlined this impression.

After Sofia, the mountains got higher. We crossed four, more than 3,000 meters high, over a distance of 230 kilometers.

We circumnavigated a huge, upland reservoir with clear, turquoise water, fantastic views after every bend. The riding was so demanding, so satisfying. Cold, wayside mountain spring water every few miles helped to cool our heads.

Our daily energy supply was always at hand. There were fresh figs, plums and grapes growing wild along the road. But promising alternatives serving local specialties were always welcome - the most memorable being the ‘Cantina’, little more than a roadside shack. Hungry and thirsty as always, we were served a simple meal of spicy, grilled meat with roasted tomatoes and onions, prepared by a wonderful old man who told us that we had just eaten all his supplies for an entire day, as he never stored ingredients for more than 15 meals because otherwise the shed would get robbed by night!

And this was just one example out of so many stories on our tour that showed the boundless hospitality, kindness and joie de vivre of the inhabitants of the Balkans. It is hard to describe what you feel when you are utterly thirsty, and you discover a little shed in the middle of nowhere where an old farmer selling watermelons for 80 cents a piece rejects your money, smiles and nods.

In the slipstream of a herd of sheep, we passed the Greek border.

Arriving at the tourist town of Orestiade we had to ask ourselves: who on earth chooses this city for vacation? Loads of tourists and tourist-shops, ultra hot, no sea, no beach, no nothing. Instead, soldiers and camouflaged vehicles passed us on a regular basis.

The Turkish border seemed to be close.

There are only two checkpoints between Greece and Turkey and with loads of kilometers still to go to the border, we were already passing watchtowers and parked armadas of old tanks, being maintained for eventual use. The atmosphere was tense.

One of us had lost his passport in Sofia. At the Greek border, thanks to some tourists being able to speak some German, the border officials turned a blind eye to the scrap of paper our guy had gotten at the German embassy in Sofia. We were lucky that time. But when approaching the Turkish border, flanked by dozens of national flags, the armed troops immediately put our debating about the right tactics for our passport-less guy to bed. We had entered the zone in between the countries. After some irrelevant back and forth with a supervisor guy, our man was escorted into the police station. The police officers took their own sweet time to decide his destiny, but this time, we were fucked. He had to take the bus back to the German embassy in Thessaloniki to get proper travel documents. Darkness was already falling and riding circles in front of the police station couldn’t protect us any more from armadas of Balkan mosquitoes so we decided to move on.

Downhearted by the border experience, it was a calm and hard ride, accompanied by muezzins singing throughout the night, even in the remotest and darkest areas we crossed. I won’t forget the feeling of that night ride.

Fresh tarmac had been kind of an exceptional thing for quite some time so a long descent on super fresh tarmac raised the mood of the whole team by 100%. We felt that we must be very close to the coast: could we really taste salty air? Then, after another demanding gravel climb through dark fields, fleeing some wild dogs in a village, the sun emerged out of the ocean right in front of us. We came to a stop to relish the moment. Overwhelmed by the beauty of that moment, by and by some of us fell asleep right there on the warm tarmac. The rest watched the spectacle from the comfort of a roadside ditch, and let their minds wander to the horizon, to Istanbul.

Spending the night in the Turkish ‘tourist paradise’ of Sarköy felt strange. Prices for a hotel room varied according to the number of visible tattoos of the person asking, and for the first time on our tour we didn’t feel welcome. The bizarre presence of huge national flags on every square and on exterior walls added to this uneasy feeling. We realised that we had entered a very different culture.

Meeting at 4 o’clock in the morning to hit the road to Istanbul, no one shed a tear for Sarköy.

Harsh and salty head- and side-winds bid us welcome on the curvy coastal road.

But another spectacular sunrise revealed a lunar-scape with serpentine roads leading us into a vast coastal mountain-chain, climb by climb.

The asphalt hairpins were followed by rough and steep gravel ones, and in combination with the continuing winds, these were by far the most intense climbs of the whole tour.

No less intense was the scary downhill ride into a small fishing village that followed – so steep that we even got faster while skidding! I still wonder how our tires survived. After ensuring that all legs were still in place we devoured everything a flying Börek-seller had, and drank some of his self-made brandy to calm our nerves after that breakneck descent.

We entered civilization again in the form of a two-lane highway filled with potholes too deep for any road bike tyre and without any kind of road markings. Together with the fucking headwind making everyone stand still if they took power off the pedals for three seconds, it was a complete nightmare; we were on our last legs. Too exhausted even to be angry about the 40-tonners rushing past us with inches to spare, we stopped at nearly every gas station to flee the crazy traffic, like they were some kind of sacred haven of recovery. Reaching Istanbul seemed impossible.

When night fell, we chose a longer, parallel route in the hope of meeting less traffic, but we ended up in a Turkish wedding which completely blocked the street, with dozens of people dancing to live music and celebrating.

We had no choice but to get ourselves into this party. We were well received by the celebrating crowd and served fruit juices before we could say ‘hello’ and dance our way through!

With another 30 kilometers to go, despite several people we asked claiming that we were already in Istanbul, we decided to take the short cut and return to the highway – which meant taking a night-ride on a four lane inner-city highway. Filled to the brim with adrenaline and with all the motorists staring, weaving or honking at us - even the police just looked on and smiled - we flew directly into the heart of the city and only stopped when we reached Taksim Square.

We had set out as near strangers, but we arrived as soul mates. I can’t wait to reunite with the boys and hit the road again. With those guys, you never know what might happen in the next ten seconds. What better recipe is there for adventure?

A journey inside the legendary Reynolds

s the samurai sword glides cleanly through your neck, it’s unlikely that your last thoughts will be of the meticulous folding and layering of steel that went into the blade’s manufacture. With any luck, the tangled whirl of your brief existence will flicker through your fading consciousness as carotid claret sprays luridly all around. But sword aficionados – especially those whose lives depended on their blades – had a keen interest in steel and its structural qualities. The men who made those blades became legends.

As you glide cleanly through the rush hour traffic, it’s similarly unlikely that your mind will dwell upon the processes that resulted in your bike’s frame behaving as it does. But bike aficionados give a great deal of thought (and money) when choosing a frame material. The varying qualities of different metals – stiff, superlight carbon, imperious titanium, lively steel – all give a different ‘feel’ to the ride, and bring their own distinct characteristics.

And of the men and women who make these frames, many are now legends. When it comes to steel, one name stands out: Reynolds.

But it is not frames themselves for which Reynolds are most famous, but the simple steel tubing needed to construct them. Their slender, elegant tubes have carried the winners of 27 Tours de France and made the company a household name around the world.

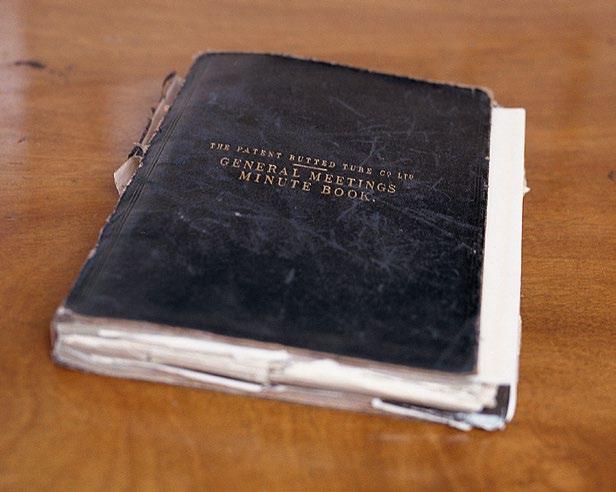

It all began with nails. John Reynolds – the man who started it all – was born the same year as the Battle of Waterloo (that’s 1815, fact fans). At 26, in 1841, he founded a company producing ‘cut’ nails – nails stamped out from rolled iron. The company became very skilled at powered metalworking processes. Years passed, the business thrived, and when the bicycle boom of the 1890s began exciting industrialists across Britain, John’s grandson Alfred turned his mind to the possibilities of manufacturing seamless steel cycle tubing, and, more importantly, to overcoming a problem which was troubling the bicycle builders of the time – how to overcome the weaknesses caused by joining thin tubes to relatively heavy lugs. Before long, Alfred had cracked it, devising a means of manufacturing tubes whose wall thickness increased at the ends only, without increasing the outside diameter, giving the cycle builder the much needed extra strength at the joints and eliminating the necessity of inserting a liner into each end of a tube, which, until then, had been the only means of achieving this.

In 1898, the Reynolds Tube Company was officially founded and it has remained at the forefront of bicycle production ever since – barring a few years during the two world wars, when work for the war effort took over. This led into tubing for aviation, and the ongoing quest for lighter, stronger tubes – a quest which bore fruit in 1935 in the form of the now world-famous Reynolds 531. The ‘5,3,1’ figures are the ratio of the three main elements in the steel’s chemical composition. Now you know.

Reynolds as a business has diversified and grown into many areas of engineering, embracing new materials including titanium, aluminium and carbon fibre. They’ve been called upon on to make all sorts of things, from Spitfire wing struts to flamethrower parts and even the oxygen tanks used by Edmund Hillary when he conquered Everest. One of these original tanks ended up being used as a gong, calling the Lamas to prayer at the monastery of Thyangvoche at Khumvu, high in the Himalayas. What a strange journey Reynolds steel has made from those first cut nails of 1841.

The bicycle tubing’s a tiny part of what Reynolds do now, but to cyclists there will always be something reassuring about those familiar green and gold labels bearing the legend ‘531’, ‘753’ or, if you’re very lucky, ‘953’.

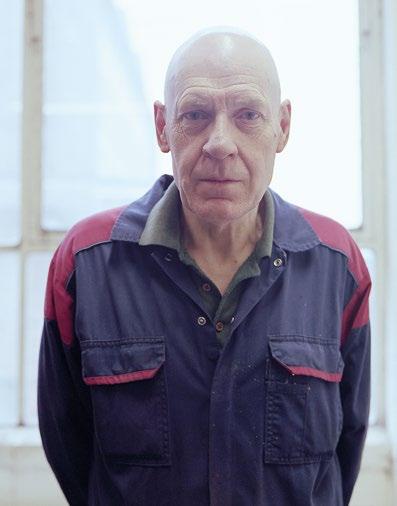

When photographer Chris Lanaway went to visit the hallowed Reynolds production plant in Birmingham, he was struck by the “industrial aroma”, the orderly arrangement of machines and men, the prevailing sense of calm efficiency. Through a door painted in Reynolds’ signature livery, two old prototype frames by British bicycle builders hang proudly above the vast machine that draws each tube to a specified diameter.

Tucked away in the corner lies what Chris describes as “some form of torture chamber”, a large machine “encased in a steel container which when fired up unleashes repeated banging that resembles a mid-summer thunder storm rumbling through the factory floor”. This machine produces fork blades and oval-shaped tubes by a cold forging process which forces the metal into shape.

Once finished, each tube set is meticulously inspected and carefully boxed up; a selection of boxes sit neatly beside the inspection area labelled with the names of individual frame builders awaiting their delivery.

It may be 20 years since steel left the pro peloton, but it continues to fuel the growing cottage industry that is bespoke frame building. The number of independent frame builders has seen a happy resurgence in recent years, as more cyclists opt for characterful, custommade steel over mass-produced aluminium and carbon frame sets. Earlier this year the Madison-Genesis cycling team announced that their riders would be competing on 953-built bikes, saying “in 953, Reynolds have a steel tubeset to trump Titanium, clawing back some much needed, long-lost ground to the favoured modern materials – stainless, stiff, competitively light yet still retaining that unmistakable compliant and roadconnected ride feel for which steel is famous.” words Jet McDonald / jetmcdonald.com illustration Matias Fiori / re-robot.com

More than a century after the release of the first double butted tube, steel remains the stuff of legend.