8 minute read

PHILOSOPHY WAS ‘LET’S GIVE IT A GO.’”

To watch the footage of Trimble riding on YouTube is a beautiful thing. Something that can rival any Tour de France clip for get-out-and-ride inspiration. It’s no surprise the story got picked up on the news, though how it happened was pure serendipity. Mike B and Mike T were simply cruising around the Pittsburgh Pirates’ baseball field, where the wide, flat sidewalks make for a good first test-ride.

After a little while they realised they were being watched with interest by a couple, also on bikes. The man who eventually introduced himself turned out to be the assistant editor at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. The small article Mike was expecting turned out to be a double page spread, which triggered both a flurry of online attention and a flurry of orders from more people, far and wide, who needed his help to saddle up.

San Francisco-based Josselyn Crane has one arm nine inches shorter than the other. She now rides with custom-made Maestro handlebars that allow full piloting control on the left side, afforded by a double-pull handlebar and grip shifter. He’s also in the process of building a rig for a man with one leg eight inches shorter than the other.

Making these dreams come true is, for Mike, quite a lot like dreaming. He spent some time sat on Mike’s cruiser in the workshop, visualising the solution, arms tucked behind his back.

The trick, he says, is re-imagining the bicycle, without corrupting the essence of it. Many people who saw the article on Mike Trimble rang him to say the better solution would have been a three-wheeled recumbent. “But that wasn’t the idea,” he says, incredulous. “Mike wanted to ride a bike!” e One thing always leads to another. For Chris Sleath, it all begin with a dream to restore vintage bikes. He began working on classic racing machines from the 1950s and 60s, and needed a way to fund the habit.

Last year Mike received a brown envelope from the City of Pittsburgh and, suspecting a sinister bill, left it on his shelf for some time, afraid to open it. “I thought it was back taxes!” When he finally did, it turned out to be a letter informing him he had been nominated to receive the ‘keys to the city’ (quite an honour) for his work making special bikes.

So if you’re ever in Pittsburgh on 6 December don’t forget to celebrate Michael Brown Day. If it’s not snowing you could go for a ride around the smooth, wide sidewalks that circle the Pirates’ ground. Mike still doesn’t know who nominated him. The list of suspects is probably quite long.

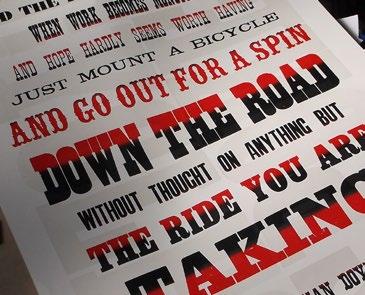

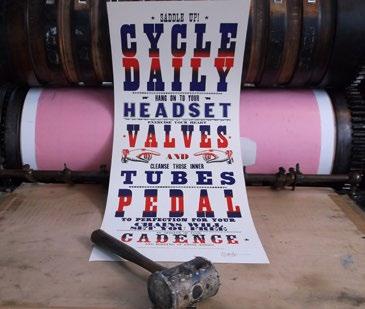

Why not create bicycle-related prints, and sell them?, he thought. Although lacking any formal training, he’d always had an interest in design and illustration, so he did a short, self-initiated printmaking course, then began helping out at a printmaker’s. Then, as these things do, the bicycle art began to take over from the bikes themselves. Soon, Chris found that he’d founded Dynamoworks, and was busy producing limited edition typographic screenprint and letterpress posters, all with a cycling theme.

Boneshaker first met Chris at the inaugural Bespoked Bristol Handmade Bicycle Show, back in 2011. We shared a stall, several beers and even more stories with him over that sun-bleached weekend. Talking to him brings the world of printmaking alive, and reveals parallels between it and the world of cycling. “There’s an immediacy, a direct contact between me and the created thing,” he says. He tries wherever possible to work without involving computers, so that “the process is not filtered through a screen, in the same way that travelling by bicycle puts you immediately in touch with the world around you, instead of filtering it through glass. It’s about that heightened awareness, being in the environment, feeling, seeing, smelling, hearing – all those things that are going on when you’re on a bike.” e In a past life he’d worked as a scene painter and set carpenter, so the old wooden blocks of letterpress had an immediate appeal. “When you pick up a piece of type, it’s a bit like being a kid again, they’re like the old-fashioned wooden play blocks”, he says. Chris rides in every day along the river to work as a technician at Edinburgh Printmakers, the oldest, biggest open-access print studio in the UK. “It’s a wonderful place,” he says, “a place where anyone can come in and have a go at lots of different kinds of printing.” When he can, he heads out of the city, up the Tweed Valley to Robert Smail’s Printworks, an atmospheric, National Trust-owned working museum in the Scottish Borders. “I’m very lucky to be able to use it, this amazing old place, full of history, with huge mountains just outside the window. The oldest continually inhabited house in Scotland is just around the corner. It’s all very beautiful.” The printworks was bequeathed to the Trust in the 1980s, but is still set up as it was in the 1940s, when every town used to have a small jobbing printworks, much as many towns used to have their own bike builder. Things changed dramatically in the 1960s, when cheaper, quicker offset litho printing became the industry standard – and letterpresses were scrapped in their thousands. “They were pushing them out of the windows, selling them for scrap, leaving them to rust in car parks.” Now, much as there is a resurgence in handmade bicycles, there’s a small fire burning anew for traditional printing processes like letterpress. James Lucas, Boneshaker’s beardy founding editor, has also helped establish the Letterpress Collective, another open workshop in Bristol aimed at ‘bringing slumbering presses back to life’. Part of the attraction was a form of creativity that is tactile, rhythmic, immediate. People are always asking Chris “why don’t you do it all digitally?” His answer is simple. “I’m not interested in looking at a computer. I like being hands-on. I like getting dirty. I like doing it this way. It’s a labour of love. Same as I could get the bus to work – but I like riding my bike in instead.” e The prints are designed around memorable cycling quotes. “I’ve read a lot of books about cycling and quite a few of them just jumped out of the page,” he says, despite the fact that “cyclists aren’t particularly well-known for saying insightful or inspiring things because they’re usually interviewed after they’ve just ridden a huge race and they’re completely shattered.” But he’s found some good ones: Italian racing legend Fausto Coppi’s “Age and treachery will overcome youth and skill”, JFK’s “Nothing compares to the simple pleasure of riding a bike” and visionary architect Sir Bertram Clough Williams-Ellis’s “Cherish the past, adorn the present, construct the future”, inked out above a huge spanner. e Chris begins each print with letterpress, then, for the screenprints, there’s a quick stint on the computer, “just using it as a photocopier really, and then blowing the whole thing up,” in order to prepare the design as a screen, so that colours can be added. He also creates posters that are pure letterpress from start to finish. “They’re great,” he says, “but they take much longer to do.” But you can tell that this slowness is part of the appeal. “Often when I ride, I ride at a speed that means I can really enjoy the heightened awareness that cycling brings, and when I see something interesting I’ll swerve off down a side road or stop to investigate. I get that with printmaking too; I can go off in different directions, it doesn’t matter if I make mistakes. They’re just happy incidents that can take the work to new and interesting places. It’s a lot like being on a bike, you just set off and let it all unfold...” e www.dynamoworks.co.uk

Words & Photos: Marko Šajn

The infamous ‘spring classics’ hold a special place in many a cyclist’s heart. These are tough one-day races like the Tour of Flanders, Liege-Bastogne-Liege and Paris-Roubaix that typically include horrible roads and a lashing from the elements. The ridiculous terrain and bad weather certainly contribute to their masochistic allure, but the major attraction for me is the stories surrounding these fabled rides.

The stories from a hundred years ago when the idea for such races first emerged (usually to promote a local newspaper), the stories of blizzards (like the one that harried San Remo-Milan in 1910) why the start points and routes keep changing (to avoid landslides, or to include a particularly hazardous cobbled descent), and the ones explaining why they didn’t just use normal roads and make it easier (where’s the fun in that?). Cycling is a series of amazing stories written over and over again, and yet we still read and enjoy them. It’s a sport that makes me feel like I know everything and nothing about it at the same time. I see professional cyclists on a TV screen and I can easily imagine being there; everything seems so familiar and natural, but the reality is very different. It’s all planned out: a theatrical drama to benefit the sponsors, a moving billboard orchestra peopled by superhumans.

But like any other orchestra it has to be tuned just right; in order for it to work everyone has to know their place. It’s a constant search for perfection, and if I had to choose one word to describe cycling, it would definitely be ‘perfection’.

The classic races are a true test of this perfection, as teams work hard all year round to ensure they have the best equipment, but it can all go to hell with one unforeseen fault. The riders train all winter only to face the possibility of getting scattered across the cobbles in the first mile, which could ruin a whole year for them. But if it all goes right and the equipment works like it has to, and luck is on the riders’ side, they get to punch the air above the finish line, stagger to the podium and become immortal alongside Merckx, Coppi, Boonen… a dream that any professional rider is willing to risk their life for. I love watching these races because I would like to take part in them one day, too. But I know it’s too late for me to do that on a professional level. So I’ve devised my own way of tasting the grim-faced glory of the spring rides: The Classics Experience.

It’s a project we’ve been organizing for the past few years; through it we try to bring road racing closer to people who started cycling too late to get into it professionally, or the ones who have never been interested in the racing part of cycling at all. Basically, people like me. On the day of a given Classic race, such as Paris-Roubaix, we do a tribute ride. We happen to live near the capital of Slovenia, so that’s where we usually stage them – but the geographical location isn’t want matters.

The start, finish and most of the segments of the ride are thematically and technically similar to the original race. Participants are divided into groups and every group takes care of its riders just like they do in the pro peloton. In this way the participants get to experience the thrill of racing and the intense camaraderie that unites the pro tour teams. It’s not a race but it definitely isn’t a tourist ride either.

This project has brought unexpected moments of selfknowledge and vastly deepened my understanding of bike racing, but most importantly, I’ve gained new friends that I know I can rely on when I don’t want to ride alone. For as long as I can remember, cycling has given me a satisfaction unlike anything else, and the fact that I can share that with other people is what gives me the energy to work on projects like the Classics Experience.

If you feel a sense of longing when you realise you’ll never battle the lethal cobbles of the Tour of Flanders or suffer on the inclines of La Doyenne, then stage a Classics Experience of your own. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

Things change and things don’t change.

Things change and things don’t change. We’ve worked with New Orleans historian and cyclist Lacar Musgrove across several issues of Boneshaker, and a while back she shared with us a scrapbook created by members of the Louisiana Cycling Club towards the end of the nineteenth century. We couldn’t resist reproducing a few excerpts from this fascinating, crumbling old collection of thoughtful asides, playful poems, caricatures and cameraderie that shows that in more than a century of riding so much has changed – the machines, the clothing, the roads – but the heart of ‘cycledom’ remains reassuringly the same.