T

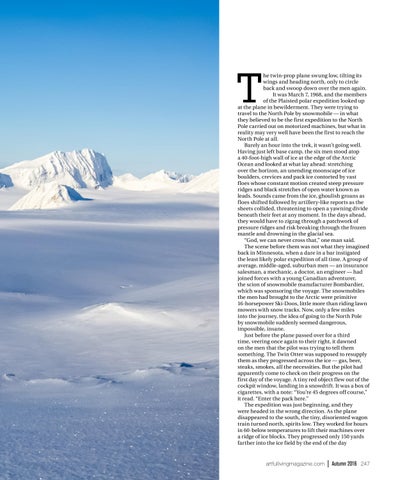

he twin-prop plane swung low, tilting its wings and heading north, only to circle back and swoop down over the men again. It was March 7, 1968, and the members of the Plaisted polar expedition looked up at the plane in bewilderment. They were trying to travel to the North Pole by snowmobile — in what they believed to be the first expedition to the North Pole carried out on motorized machines, but what in reality may very well have been the first to reach the North Pole at all. Barely an hour into the trek, it wasn’t going well. Having just left base camp, the six men stood atop a 40-foot-high wall of ice at the edge of the Arctic Ocean and looked at what lay ahead: stretching over the horizon, an unending moonscape of ice boulders, crevices and pack ice contorted by vast floes whose constant motion created steep pressure ridges and black stretches of open water known as leads. Sounds came from the ice, ghoulish groans as floes shifted followed by artillery-like reports as the sheets collided, threatening to open a yawning divide beneath their feet at any moment. In the days ahead, they would have to zigzag through a patchwork of pressure ridges and risk breaking through the frozen mantle and drowning in the glacial sea. “God, we can never cross that,” one man said. The scene before them was not what they imagined back in Minnesota, when a dare in a bar instigated the least likely polar expedition of all time. A group of average, middle-aged, suburban men — an insurance salesman, a mechanic, a doctor, an engineer — had joined forces with a young Canadian adventurer, the scion of snowmobile manufacturer Bombardier, which was sponsoring the voyage. The snowmobiles the men had brought to the Arctic were primitive 16-horsepower Ski-Doos, little more than riding lawn mowers with snow tracks. Now, only a few miles into the journey, the idea of going to the North Pole by snowmobile suddenly seemed dangerous, impossible, insane. Just before the plane passed over for a third time, veering once again to their right, it dawned on the men that the pilot was trying to tell them something. The Twin Otter was supposed to resupply them as they progressed across the ice — gas, beer, steaks, smokes, all the necessities. But the pilot had apparently come to check on their progress on the first day of the voyage. A tiny red object flew out of the cockpit window, landing in a snowdrift. It was a box of cigarettes, with a note: “You’re 45 degrees off course,” it read. “Enter the pack here.” The expedition was just beginning, and they were headed in the wrong direction. As the plane disappeared to the south, the tiny, disoriented wagon train turned north, spirits low. They worked for hours in 60-below temperatures to lift their machines over a ridge of ice blocks. They progressed only 150 yards farther into the ice field by the end of the day

artfullivingmagazine.com | Autumn 2016 247