Asian & Pacific Islander American Studies

Francis Tanglao Aguas, MFA

Sasikumar Balasundaram, PhD

R. Benedito Ferrão, PhD

Monika Gosin, PhD

Tomoko Hamada, PhD

Roberto Jamora, MFA

Jenny Kahn, PhD

Theresa Ronquillo, Joanna Schug, PhD

Stephen Sheehi, PhD

Chinua Thelwell, PhD

Lynn Weiss, PhD Andrea Wright, PhD

Publisher

Francis Tanglao Aguas

Monika Van Tassel

Vivian Hoang '24 Nina Raneses '22

Design Editors

Vivian Hoang '24

Joey Houska '24

Cori Ingram '23

Diana Kim '25

Yannira Lopez Perez '22 Brandon Nguyen '24

Nina Raneses '22

Angelique Vo '22

Staff Writers

Eddie Choi '22

Ninjin Gankhuleg '23

Vivian Hoang '24

Emily Key '23

Calvin Kim '22

Shreyas Kumar '21

Aidan Lowe '23

Sreya Malipeddi '23

Myra Simbulan '25

Mey Seen '23

Sumie Yotsukura '22

Rayna Yu '21

Cori Ingram '23

Effie Zhang '24

Fiscal Coordinator, Global

Academic &

Studies

Chief Organizational

Co-Editors in

Management Lead

Graphics Lead

TABLE OF CONTENTS 02 04 05 13 30 33 35 37 40 43 48 50 52 54 56 59 63

FromtheDirector: FromtheDirector:

CelebratingAPIA CelebratingAPIA &theAsian &theAsian Centennial Centennial

Two years ago, when I first took over as the director of the APIA program, we were in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Two years ago, when I first took over as the director of the APIA program, we were in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, attending Zoom classes, headed towards a violent attack on the Capitol, and dealing with rising anti-Asian hate While attending Zoom classes, headed towards a violent attack on the Capitol, and dealing with rising anti-Asian hate. While unfortunately we still continue to face many of these same issues today, my goal here is to celebrate and highlight the strong we still continue to face many of these same issues today, my goal here is to celebrate and highlight the strong counter-narrative that we are creating in APIA and with the Asian Centennial in the face of these challenges counter-narrative that we are creating in APIA and with the Asian Centennial in the face of these challenges.

Since 2019, when APIA officially became a major, we have grown from a graduating cohort of four students to the class of 2022’s Since 2019, officially became a major, we have grown from a graduating of four students to the class of 2022’s cohort of seven majors and one minor with an expected graduating cohort of 10 majors next year Our growth in majors is due in cohort of seven majors and one minor with an expected graduating cohort of 10 majors next year Our growth in majors is due in large part to our ability to create an inclusive space that allows critical analysis of U S institutions and attitudes, which is large part to our ability to create an inclusive space that allows critical analysis of U S institutions and attitudes, which is especially needed today It is also reflective of our growth in affiliate faculty such as professors Esther Kim, Jason Chen, and especially needed today. It is also reflective of our growth in affiliate faculty such as professors Esther Kim, Jason Chen, and Jamel K. Donnor from the School of Education, professor Laura Guerrero from the philosophy department, and in adjunct faculty Jamel K Donnor from the School of Education, professor Laura Guerrero from the philosophy department, and in adjunct faculty members such as professors Theresa Ronquillo, Roberto Jamora, and Sasikumar Balasundaram, which has allowed us to offer a members such as professors Theresa Ronquillo, Roberto Jamora, and Sasikumar Balasundaram, which has allowed us to offer a broader variety of courses seen through a more diverse set of disciplinary lenses. broader variety of courses seen through a more diverse set of disciplinary lenses

This year also marks the centennial commemoration of the first Asian student and likely the first student of color at W&M Pu This year also marks the centennial commemoration of the first Asian student and likely the first student of color at W&M Pu Kao Chen More than a celebration of one individual, the Asian Centennial has allowed us to highlight the history and legacy of Kao Chen More than a celebration of one individual, the Asian Centennial has allowed us to highlight the history and legacy of Asian, Pacific Islander, and Middle Eastern/Muslim students, faculty, and staff The Asian Centennial also contextualizes their lives Asian, Pacific Islander, and Middle Eastern/Muslim students, faculty, and staff. The Asian Centennial also contextualizes their lives in the racial climate of their times. in the racial climate of their times

In doing so, we were able to develop a platform for collaborative programming that opened conversations on how to continue to In doing so, we were able to develop a platform for collaborative programming that opened conversations on how to continue to build a more inclusive community build a more inclusive community.

This has meant bringing in renowned authors such as Pulitzer Prize winner Dr Viet Thanh Nguyen and supporting prominent artists has meant bringing in renowned authors such as Pulitzer Prize winner Dr Viet Thanh Nguyen and supporting prominent artists such as Roberto Jamora, Rinabeth Apostol and Marissa Aroy, all of whom have diversified our physical spaces All the while, we such as Roberto Jamora, Rinabeth Apostol and Marissa Aroy, all of whom have diversified our physical spaces All the while, we have recognized our connections to the past, as seen in our dedications of the Arthur Matsu Arcade at Zable Stadium and the have recognized our connections to the past, as seen in our dedications of the Arthur Matsu Arcade at Zable Stadium and the Arthur Matsu historical marker and in the reading of the W&M Charter in multiple Asian languages at Charter Day My hope is that Arthur Matsu historical marker and in the reading of the W&M Charter in multiple Asian languages at Charter Day. My hope is that the amazing energy we have witnessed this past year allows us to continue building more sustainable projects and programming the amazing energy we have witnessed this past year allows us to continue building more sustainable projects and programming for the future for the future.

Finally, a big thanks and shout out to my collaborator, brother Bruin, and fellow co-chair of the Asian Centennial, Professor Francis Finally, a big thanks and shout out to my collaborator, brother Bruin, and fellow co-chair of the Asian Centennial, Professor Francis Tanglao Aguas Thanks for sharing this fun and crazy year Next year, I am on research sabbatical researching, writing, and Tanglao Aguas Thanks for sharing this fun and crazy year Next year, I am on research sabbatical researching, writing, and recharging In the meantime, I am delighted to announce that professor Stephen Sheehi has agreed to serve as the interim director In the meantime, I am delighted to announce that professor Stephen Sheehi has agreed to serve as the interim director of APIA in my absence of APIA in my absence.

I know the program will be in great hands I can’t thank enough all my colleagues in APIA whose efforts and support has ensured I know the program will be in great hands. I can’t thank enough all my colleagues in APIA whose efforts and support has ensured the continued success of our program and has made directing APIA so rewarding. I also cannot thank enough our students, whose the continued success of our program and has made directing APIA so rewarding I also cannot thank enough our students, whose participation in research projects, in community building (Yeah, Asian Centennial Ball!), and in everyday interactions in class and participation in research projects, in community building (Yeah, Asian Centennial Ball!), and in everyday interactions in class and outside make being at William & Mary so joyous and worthwhile. outside make being at William & Mary so joyous and worthwhile

ProgramDirectorofAsian& ProgramDirectorofAsian& PacificIslanderStudies, PacificIslanderStudies, ProfessorofSociology,Co-Chair ProfessorofSociology,Co-Chair oftheAsianCentennialatW&M oftheAsianCentennialatW&M

DeeneshSohoni, DeeneshSohoni,

Introducing: Introducing: TheCentennialEight TheCentennialEight

Oddly enough, I formed my relationship with the class of 2022 online Oddly enough, I formed my relationship with the class of 2022 online through Zoom screens or over social media before I was able to ever through Zoom screens or over social media before I was able to ever interact with them in person. I had heard about each one of them interact with them in person I had heard about each one of them through their involvement in our community, whether it be advocacy, through their involvement in our community, whether it be advocacy, performance, research; it is truly a testament to the impact each of performance, research; it is truly a testament to the impact each of these individuals has had on William & Mary that I knew them by their these individuals has had on William & Mary that I knew them by their talents before properly meeting any of them. talents before properly meeting any of them.

Beyond being classmates, we are a coalition who has witnessed and Beyond being classmates, we are a coalition who has witnessed and endured a number of historical moments From the pandemic to Stop endured a number of historical moments. From the pandemic to Stop Asian Hate, it has been far from easy to be a member of this community Asian Hate, it has been far from easy to be a member of this community on top of our own personal challenges. In this issue, you will find many of on top of our own personal challenges. In this issue, you will find many of us, alongside our peers, discussing the discovery of our identities. Many us, alongside our peers, discussing the discovery of our identities. Many of us have sought out communities that we did not have the privilege of of us have sought out communities that we did not have the privilege of having in our hometowns or high schools. having in our hometowns or high schools

Through our coursework, involvement in student organizations, and Through our coursework, involvement in student organizations, and confiding in one other, we have arrived at the end of our undergraduate confiding in one other, we have arrived at the end of our undergraduate journeys having successfully navigated many of these challenges. Now, journeys having successfully navigated many of these challenges. Now, we get to celebrate. We celebrate unapologetically being ourselves. We we get to celebrate We celebrate unapologetically being ourselves We celebrate taking up space. We celebrate the Asian Centennial and the celebrate taking up space We celebrate the Asian Centennial and the early Asian students who arrived at this institution during time periods early Asian students who arrived at this institution during time periods we may not be able to relate to, but share their struggles all the same we may not be able to relate to, but share their struggles all the same. We honor some of these students through this journal's namesakes, Art We honor some of these students through this journal's namesakes, Art Matsu '27 and Hatsuye Yamasaki '37, and we do so in the background of Matsu '27 and Hatsuye Yamasaki '37, and we do so in the background of our cover photo, which was taken in front of Brown Hall, Yamasaki's our cover photo, which was taken in front of Brown Hall, Yamasaki's dorm. During her time at William & Mary, Yamasaki was elected hall dorm During her time at William & Mary, Yamasaki was elected hall president by her peers a noble feat for who we believe to be the first president by her peers a noble feat for who we believe to be the first woman of Asian descent to attend Willam & Mary woman of Asian descent to attend Willam & Mary.

So, congratulations, Centennial Eight, for dealing with the challenges of So, congratulations, Centennial Eight, for dealing with the challenges of our community and within ourselves while also being able to celebrate our community and within ourselves while also being able to celebrate our past, present, and future. Eddie, Andrea, Gabby, Mitchel, Calvin, our past, present, and future Eddie, Andrea, Gabby, Mitchel, Calvin, Angelique, and Sumié I look forward to seeing all of the amazing things Angelique, and Sumié I look forward to seeing all of the amazing things you accomplish Thank you for your contributions to this university, and you accomplish. Thank you for your contributions to this university, and thank you for being a shoulder to lean on, in good moments and bad thank you for being a shoulder to lean on, in good moments and bad. Here's to us and everyone who helped get us here! Here's to us and everyone who helped get us here!

NinaRaneses'22, NinaRaneses'22, Editor-in-Chief Editor-in-Chief

Photos taken by Patrick Pham 23

Photos taken by Patrick Pham 23

Hyunkyu"Eddie"Choi'22

Thesis:"WheninWilliamsburg"

rted with questions.

environment notorious for its academic rigor? Would I be in a community that is so culturally different from what

g to be the “typical” William & Mary student. But questions ey are answered, and no answer will be as clear as when osure. And so that’s what I pursued my own "twamp" virtually every student comes across during their time at nds for “typical William & Mary person.”

ical” in a setting that is structured to encourage many of growth? And what if the chef plated this setting with a demic? I realize my international upbringing already sets my rom that of the greater student body, but hasn’t COVID-19 styles to a certain degree?

y the least, we’ve all had our share of self-development journeys thanks to enty of indoor time that allowed for much-needed self-confrontation. es having forced us to make perhaps some of the greatest sacrifices, -19 has also graced us with the gift of learning to appreciate our unique and identities

ypical” in “twamp” has lost its meaning but in the most beautiful way nable My difference is not to be set apart, but rather to coexist with

SENIOR ESSAY BA, Asian & Pacific

American Studies BS, Psychology 2021 International Student Achievement Award Recipient 2022 International Student Opportunity Award Recipient 2022 Asian Centennial Service Award

Photos courtesy of Hyunkyu Eddie Choi 22

Islander

Sociology

Treasurer and External Committee Member, Filipino American Student Association, 2019-2021 Secretary, Asian American Student Initiative, 20202021 Research Fellow, Salary Equity Project for Social Justice Policy Initiative, 2021-2022

AndreaDalagan'22

Thesis:"TheEffectofAmericanPedagogyon ColonialRuleinthePhilippines"

The last time I wrote for Art & Hatsuye, I talked about why I majored in APIA While I don t think I need to recap my journey, we’re gonna need some context here Here is my love letter to APIA

In my first semester here at William & Mary, I was adamant in avoiding influences from others about what I should do, instead searching for something I completely believed in. Every conversation that started with, “You should take this APIA class,” was met with an internal eyebrow raise. I was not to be told what to do and what path to follow. I would decide.

My own curiosity eventually led me to take Asian American History with Professor Chinua Thelwell. During our first class, he asked us, “Why are you taking Asian American History?” While it seemed like such a simple question, I struggled to communicate a comprehensive answer, complicated by feelings I hadn’t taken the time to define before. How do I tell this classroom full of people about the generations of Asians before me, my own migration, and the generations after me? How do I tell them about the need to know what context I was placed in and what context I would be placing my children in? What is the American quilt that I am sewing them into by being here? In the end, all I said was, “I’m Asian,” in the hopes that the implication was enough

By taking the class, and the subsequent APIA classes afterwards, I viewed the world differently. Through APIA, I grew closer and closer to having a grasp of the millions of nuances and contexts that the world operates in. The dramatic shifts in the lights and the darks. A battered hand holding another, and a beating hand hitting another The most beautiful pictures of communities coming together with the ugliest pictures of exploitation tearing people apart.

Before, I wrote about not regretting any of it, that I would rather inch forward than live with a wool over my eyes. In the years I’ve taken APIA classes, it wasn’t always easy seeing things in my life a little differently This isn’t the kind of major you join because you think it’ll pay a sixfigure salary right out of college. This isn’t a major you join because you are enamored by a culture like a Francophile This community I joined through APIA isn’t delicate; it isn’t a fragile flower unable to withstand hardships. It’s gritty in its struggles: the fight against tokenization, fetishization, erasure Invisibility

The APIA majors I know are here because they saw themselves in it. They saw their painful experiences and the things they have pushed away for years But it was their ability to constantly envision a better future, a reality to strive for, that inspired me time and time again. This community will continue to amaze me with its faith a faith that is not born out of idealism and ignorance but one born out of trials and adversity.

SENIOR ESSAY

Photos courtesy of Andrea Dalagan 22

BA, Asian & Pacific Islander American Studies BA,

Coming into William & Mary, I was nervous. Coming from a high school in Las Vegas in which 84% of the students were students of color, and my closest friends were Asian American, William & Mary’s student body was far from familiar William & Mary is a predominantly white institution next to a theme park celebrating colonialism. I guess I wasn’t nervous so much as terrified.

To deal with the culture shock, I joined the Filipino American Student Association, where I started to feel more comfortable. It was more than just the fact that they ate adobo or loved karaoke – it was a community that I could turn to, that would just get it The upperclassmen in FASA I met and admired all had one thing in common: they were all studying Asian & Pacific Islander American Studies. So naturally, I started taking APIA classes.

In my freshman spring, I registered for Filipino American Diaspora, and for the first time in my academic career, my experiences were put front and center. It wasn’t just a single sentence in a textbook – it was in every weekly reading As a senior seminar, the readings were challenging, and the work was intimidating, but everything I learned felt significant

When I’d finally mustered the courage to go to Professor Aguas’ office hours, he sat me down and showed me why we need APIA studies Literally Watching Jin Hyuk Ho’s honors project, “Why We Need APIA Studies,” is a rite of passage amongst APIA majors, and I was no different. After that moment, I decided to become an APIA major, and I am thankful that I did With a smaller major, I was able to connect with my professors and like-minded peers I found a community that I was afraid wouldn’t exist, one that taught me how to leverage and celebrate my identity.

When the pandemic hit, I suddenly felt like I had lost that community The toll isolation took on my mental health made me unsure if I would be able to graduate at all, much less finish my APIA major But when I reached out for help, my community reemerged to support me Inspired by the words of Professor Aguas, that anything I do is APIA, I challenged myself to return to aspects of my life that I had been neglecting. My APIA capstone, an EP of songs about my Filipino American experience, fully centralized me, and in doing so, centralized APIA studies in my life

Looking back, I am incredibly grateful to be a part of this community, to be surrounded by people who revel in my successes and help me recover from my struggles My coursework and community have generated my drive towards public service, and my passion for uplifting marginalized communities, and I would not be the person I am today without it.

BA, Asian & Pacific Islander American Studies

BA, Public Policy, Phi Beta Kappa

Research Fellow, International Justice Lab at the Global Research Institute, 2019-2020

Tournament Director & Team Captain, William & Mary Mock Trial Team, 2019-2022

External Programming Committee, Filipino American Student Association, 2019-2020 1693 Scholar

2020 Freeman Fellow

2022 IPAX Performing Arts Award

GabrielleDeBelen'22 Thesis:"SongsoftheIbongAdarna"

SENIOR ESSAY

Photos courtesy of Gabriel e DeBelen 22

MitchelHosuKhim'22

Coming into William & Mary from a predominantly white high school with little to no knowledge about the history or experiences of Asian Americans, I was unaware that APIA studies even existed in any curriculum, let alone be something I could minor in.

I began my journey into APIA the spring of my freshman year taking Filipino American Diaspora after my freshman hallmate and great friend Sidney Miralao suggested I take the class with her Being a Korean American, I didn’t think this class would pertain to me in any way, but I was quickly proven wrong Professor Aguas’ lectures and the reading material opened my eyes to a history I never knew before, and I found myself relating more and more with my own experiences as a Korean American After this class, I continued taking at least one APIA class every year of my college curriculum, and now I have the honor of being an APIA minor

Joining the APIA community has allowed me to foster so many great friendships and find opportunities that I never would have had otherwise From all the cultural organizations I have been a part of, to the conferences we would travel to, I became much more aware and educated on what life as an Asian American meant.

Today, I am proud to be a Korean American, and I am proud to be an Asian American. As I reflect on my time here, I strongly implore those who are Asian American on this campus to take at least one APIA course during your time as an undergraduate. We are privileged that our school offers courses that give us representation of our own culture, and you never know how that one class can shape your view of the world.

District 7 Representative, Filipino American Student Association, 2019-2020

Internal Committee Member, Filipino American Student Association, 2019-2020

Agape Christian Fellowship

APIAMinor

SENIOR ESSAY

Photos courtesy of Mitchel Khim 22

BS, Kinesiology

Minor, Asian & Pacific Islander American Studies

Social Chair, Chinese Student Organization

CalvinKim'22

Coming to William & Mary, I knew I wanted to major in Sociology. I was also considering International Relations or English for a double major at the time, and I didn’t even know APIA Studies existed But that all changed when I walked into Professor Sohoni’s office for my first ever pre-major advising meeting. Still three credits away from being a full-time student, I was panicking and had no idea which class to take Professor Sohoni suggested that I take Intro to APIA Studies with Professor Ferrao, and my life truly changed from then on.

Intro to APIA studies did exactly what the course title said it would it introduced me to so many aspects of history, culture, and politics that I had never learned before. It was a few weeks into class when I had solidified my decision to major in APIA Studies, and I haven’t regretted that choice for a second APIA studies has given me so much more than just academic knowledge; it has given me courage, compassion, and selflove APIA studies provided me with the tools I needed to fully accept myself in so many different facets of my life.

What sets APIA studies apart from other majors is that it’s not just a major, it’s truly a family. When I joined the family, I was immediately brought into the fold by upperclassmen majors. They quickly became friends and mentors who I could turn to with questions or ask for advice The faculty in APIA were not only our professors, but also elders whose lived experiences and wisdom were valued by all students. The faculty of APIA have made it clear time and time again that their priority is their students’ wellbeing Anytime I needed an extension and that was a LOT my APIA professors were always the most flexible and accommodating to my needs. They would check in to see how I was doing, not how much progress on my paper that I was making I may have been a 6-hour drive from Philly, but thanks to APIA studies I never felt too far away from home.

APIA studies is why I am so proud of who I am as I leave this chapter of my life I have endless love and gratitude for every single professor, major, and friend who supported me throughout my time in college and challenged me to grow into the best version of myself Even before I saw it in myself, my APIA family recognized the potential I held

Thesis:"Woori:TheKoreanAmericanChurch's ExclusiveInclusion"

Asian American Student

2020-2021

of

and

2020-2021

for

and

Photos courtesy

of Calvin Kim '22 SENIOR ESSAY BA, Asian & Pacific Islander American Studies BA, Sociology Co-Director,

Initiative,

Director

Recruitment

HR, Lafayette Kids,

2020 Freeman Fellow 2021 Edward Hong Prize

Student Activism

Leadership 2022 Algernon Sydney Sullivan Award 2022 Cypher Award Recipient

BA, Government

Minor, Asian & Pacific Islander American Studies

2022 Editor-in-Chief, Art & Hatsuye

2021 Copy Chief, The Flat Hat

2021 Copy Chief, Flat Hat Magazine

Resident Assistant, 2020-2022

NinaRaneses'22

Like many of my peers, I discovered APIA at a time when I began taking a deeper look at my ethnic identity in college. Prior to being a student at William & Mary, I frankly did not discuss APIA identity with anyone, not even myself. I had always been confident enough in who I was. In fact, in most circumstances as a teenager, I avoided any opportunity to delve further into my heritage for fear that I might go through what I have ended up going through as a young adult

As I’ve reflected in a deeply personal piece I penned for Flat Hat Magazine last year, the passing of my grandmother opened my eyes to what I was missing out on. I lost my strongest connection to my Filipino heritage that day. I knew I owed it to myself from that point onward to educate myself, to ask myself the hard questions, and to be comfortable with being uncomfortable

Learning more about your identity is not a linear process. Bits and pieces will reveal themselves at times you won’t expect and opportunities you never knew you could have could arise. For me, it was taking Asian American Demography and Law my junior year with Prof Deenesh Sohoni In that course, I learned things about Asian American history that surprised, shocked, and humbled me. I gained a more personal insight into APIA in Filipino Diaspora Studies with Prof. Roberto Jamora, in which I learned more about Filipino history and culture in one semester than I had in my whole life and I even spent a year living in the Philippines!

In terms of unexpectedness, I never thought I’d be able to gain a whole new community as a result of this journey. The support from this program I’ve gotten along the way has been astounding. Thank you, APIA, for being such an unexpected but necessary part of my journey.

SENIOR ESSAY

Photos courtesy of Nina Raneses 22

APIAMinor

AngeliqueVo'22

Entering freshman year was lonelier than I expected.

There was never a part of me that felt like I truly belonged at William & Mary. Despite all of the clubs I joined to match my interests, there was never a club that particularly stood out to me or made me feel comfortable being myself. Thankfully, this all changed my sophomore year when I decided to join the Filipino American Student Association, which introduced me to APIA Studies

While in FASA, I often heard stories about the APIA program and its classes. I would overhear conversations about APIA classes Although I grew curious about what classes with unique names like “SexyRacy” entailed, I never took the time to research the APIA Studies major due to my allegiance to my STEM major Finally, during the spring semester of my sophomore year, one of the FASA seniors, David Fernandez ‘20, convinced me to take a break from my neuroscience courses and enroll in Asian Pacific American History with Professor Thelwell From then on, I was immersed in APIA studies

APIA History was truly life changing for me because it filled a void that I didn’t know I had It introduced me to a new way of learning and unlearning as we read about cultural history and experiences that previous history classes had excluded When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, and hate crimes against AAPI individuals increased throughout the country, my anger on behalf of the AAPI community heightened This anger eventually fueled my passion for advocacy and curiosity for APIA Studies as I went on to enroll in courses such as Intro to Asian & Middle Eastern Studies with Professor Wright and the famous “SexyRacy,” or “Sex & Race in Plays and Films” with Professor Aguas, which ultimately solidified my decision to major in APIA

For me, APIA has taught me the importance of empathy and compassion for others I’ve learned to have the courage to express who I am, share my experiences, and explore my identity. Most of all, APIA has taught me how to unapologetically love myself as a Vietnamese American as my Bà Nội once taught me.

Thank you to my friends and family who provided me love and support in my times of need during my four years. Thank you to APIA professors for not only endlessly encouraging me, but also for molding me into the scholar I am today Thank you to FASA and VSA for giving me the pamilya and gia đình that I longed for my freshman year.

Most of all, thank you APIA Studies for helping me appreciate myself as a Vietnamese American and being my ‘why’ when I think about why I belong at William & Mary

Thesis:"LittleSaigons:Misrepresentation,Identity,andthe VisibilityofSouthVietnamese-Americans" SENIOR ESSAY

Asian & Pacific Islander American Studies BS, Neuroscience

& External Vice President, Vietnamese Student Association, 2021-2022

7 Representative, Filipino American Student Association, 2020-2021

Vice-Chairperson, Filipino

Networking Dialogue Inc.,

of Social Media, The

Award Recipient

BA,

Co-Founder

District

District 7

Intercollegiate

2021-2022 Director

Asian Centennial, 2021-2022 2022 Cypher

2022 Outstanding Capstone Thesis Award 2022 Tomoko Hamada Award for Applied Scholarship

Photos courtesy of Angelique

Vo '22

SumiéYotsukura'22

Surprise, surprise: Francis was right.

He told me that doing APIA would enable me to find my full humanity as an Asian American. He said that the classes I’d take, the professors I’d learn from, and the friends I would meet would allow me to gain knowledge and even comfort in who I am as an Asian American and that all of this would be the most valuable part of my college experience And, lo and behold, two years later, everything has played out exactly as he said it would

But I didn’t always know it would turn out this way. I was a relative latecomer to APIA, and for a very long time, I felt like I might never actually make my way into the program I wasn’t able to fit an APIA class into my schedule until junior year, and for all my efforts, I was never able to make more than two Asian American Student Initiative meetings a semester. The longer I went unable to do anything APIA related, the less I believed I would ever find my place within the community

And then something happened. APIA became my reason for being in college my lifeline. These were the classes teaching me about my history and what it meant to be Asian American These classes taught me how to understand the world as I had always wanted but never been able to In times of confusion, loneliness, and existential doubt during the pandemic, APIA gave me a purpose. I found solace in my classes and biweekly AASI zoom meetings, in which I felt like I genuinely had a community one of the strongest, smartest, most conscientious and supportive communities I ever had the privilege of stumbling into Here was a community I could be fully myself in a way I’d never been able to before.

Getting to learn, talk, laugh, and smile in-person with all the incredible members of this community over the past year has been the greatest gift I never knew I needed This community, which I’d felt so helplessly disconnected from, became like family to me. That I leave here feeling so comfortable and confident in my Asian American self, strengths and flaws and quirks and all, is because of this incomparable community

BA,

President, Theatre Student Association, 2020-2022

Director, Sinfonicron Light Opera Company, 2021-2022

Researcher & Exhibit Designer, APM Research Project, 2021-2022

2021 Catron Grant Recipient

2020-2021

2022 Lord Botetourt Medal

SumiéYotsukura'22

HonorsThesis:"PerformingWhiteandAsianRacialization: SumieYotsukura’s“your(best)asianamericangirl,acabaret”

ESSAY

Photos courtesy of Sumié Yotsukura

22

SENIOR

Asian & Pacific Islander American Studies, High Honors

BA, Theatre, Phi Beta Kappa

Lang Legacy Scholarship for Academic Excellence in Theatre

2022 Albert E Haak Memorial Award in Theatre

2022 Tomoko Hamada Award for Applied Scholarship

2022 Art Matsu Prize for Excellence in Asian & Pacific Islander American Studies

High Honors in Asian & Pacific Islander American Studies

AsianCentennialEvents

Hanako Doherty '96, a member of the Asian-Pacific IslanderMiddle Eastern Alumni of William & Mary (APIM), visits campus during homecoming and reads the Spring 2020 issue of Art & Hatsuye. Photo taken by Mitchel Khim '22.

Patrick Canteros '20 and Emma Shainwald '20 visit the APIA tailgate during homecoming. Photo taken by Mitchel Khim '22.

From left to right: alumnus Franklin Rho '96 visits the APIM tailgate with Gabby DeBelen '22, David Fernandez '20, and Angelique Vo '22. Photo courtesy of Angelique Vo '22.

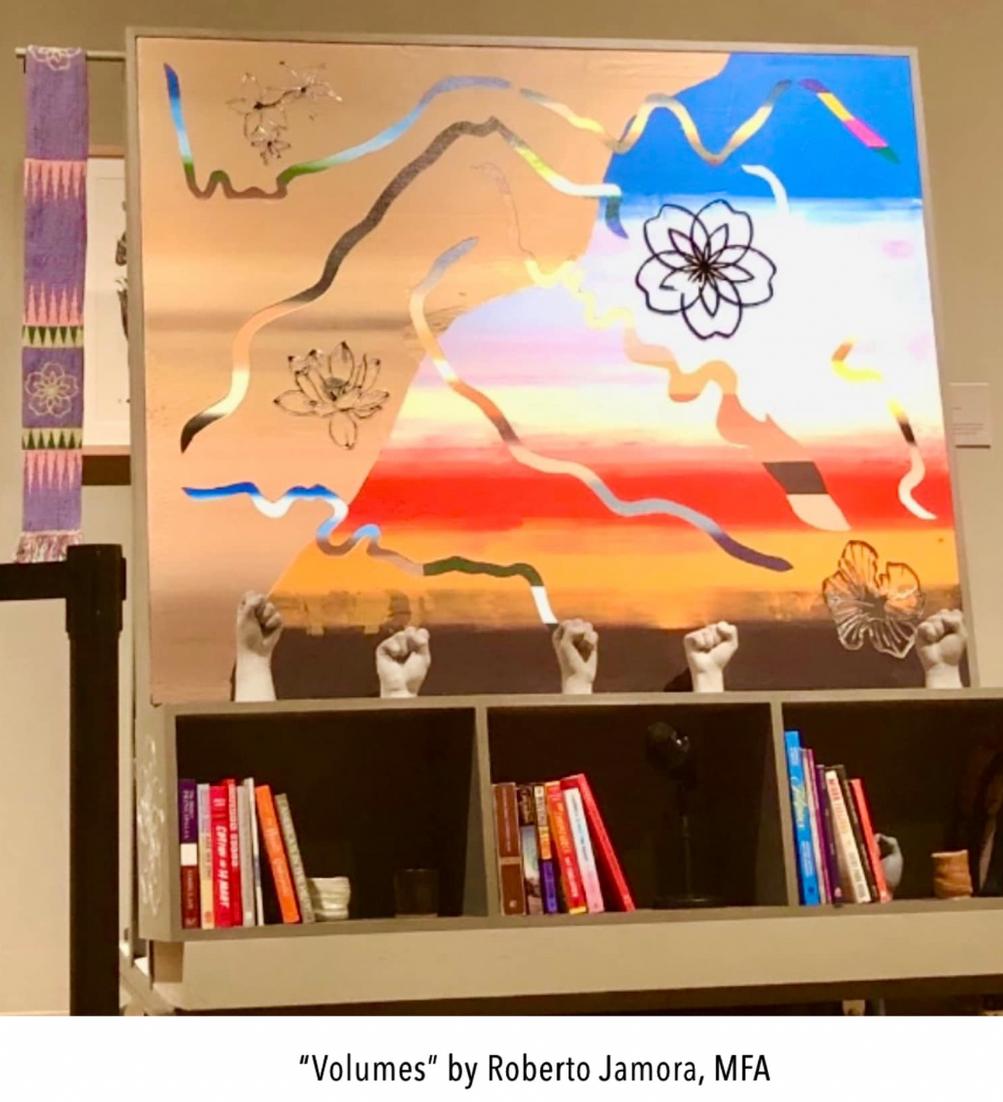

Professor Roberto Jamora delivers an Artist Talk at the Muscarelle Museum. Jamora's talk highlights his

Professor Andrea Wright shares her latest research findings at an APIA Faculty Banh Mi Lecture after being honored as the first recipient of the Jinlan Liu Faculty Research Award. Photo taken by Mitchel Khim '22.

Emmyaward-winningfilmmakerMarissaAroyvisits campustodocumentthehistoryandexperienceof AsiansatWilliam&Mary,workingalongsideWilliam& Mary'sDirectorofVideo&MultimediaLisaCrawford. PhotocourtesyofFrancisTanglaoAguas

Quan Chau '21 performs a personal rendition of "I Can Go the Distance" by Michael Bolton, a centerpiece of the Disney film Hercules. Photo taken by Vivian Hoang '24.

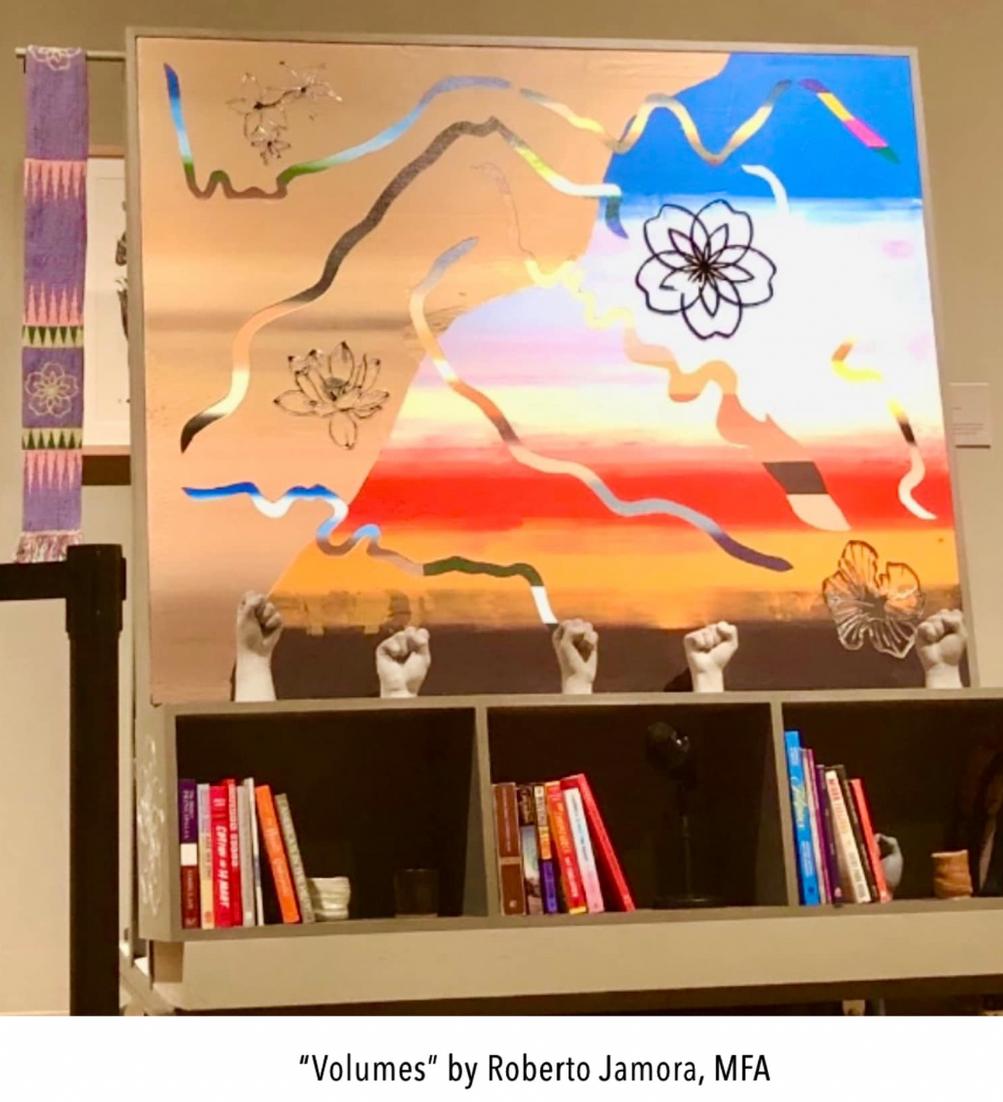

The Asian Centennial at W&M unveils Professor Roberto Jamora's artwork, "VOLUMES." This piece is inspired by the activism and leadership of APIMSW students at W&M. Photo taken by Vivian Hoang '24.

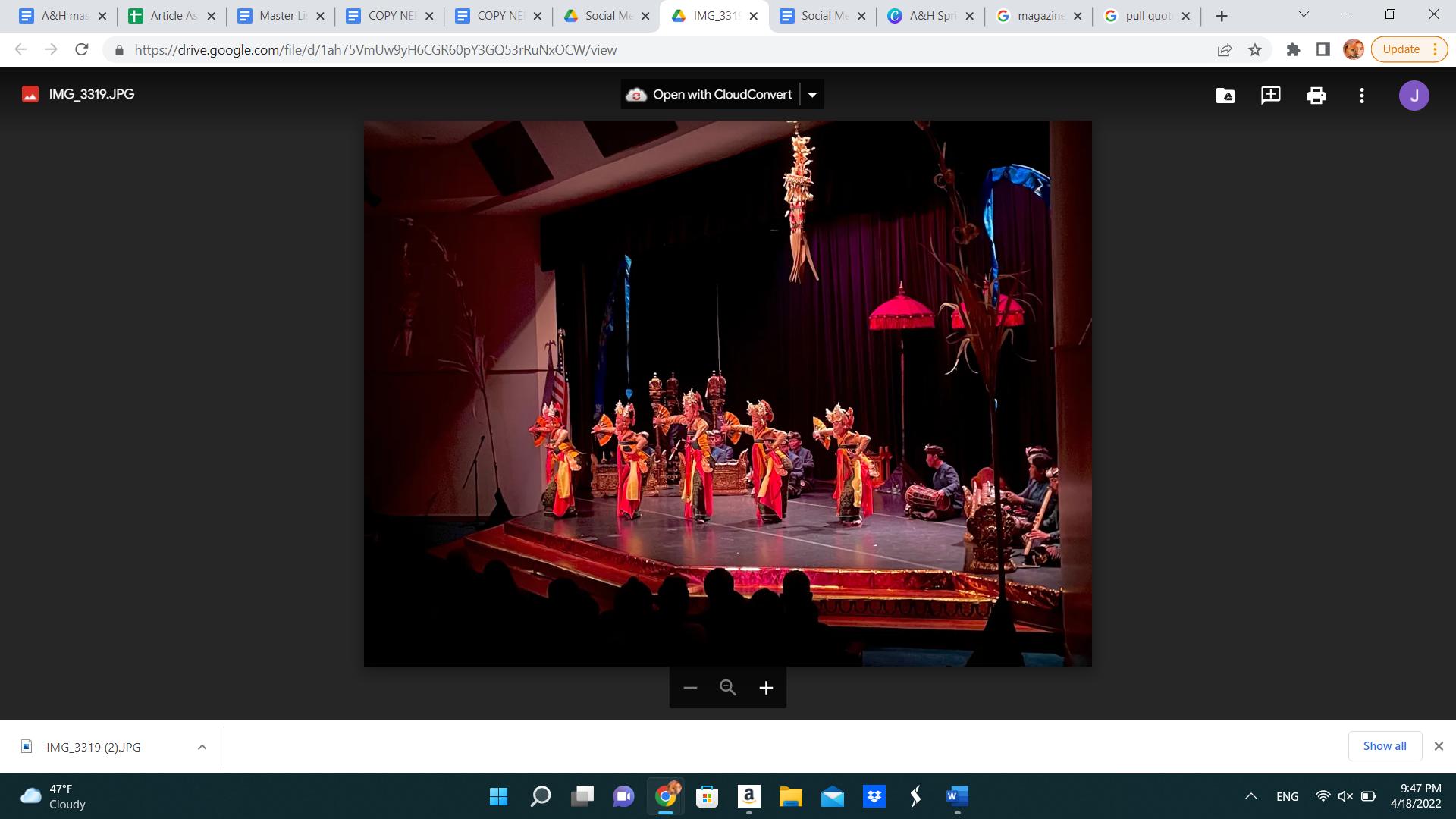

Ameya King '12 performs a traditional Kuchipudi dance at the Asian Centennial Gala. Photo taken by Vivian Hoang '24.

Hanako Doherty '96, a member of the Asian-Pacific IslanderMiddle Eastern Alumni of William & Mary (APIM), visits campus during homecoming and reads the Spring 2020 issue of Art & Hatsuye. Photo taken by Mitchel Khim '22.

Patrick Canteros '20 and Emma Shainwald '20 visit the APIA tailgate during homecoming. Photo taken by Mitchel Khim '22.

From left to right: alumnus Franklin Rho '96 visits the APIM tailgate with Gabby DeBelen '22, David Fernandez '20, and Angelique Vo '22. Photo courtesy of Angelique Vo '22.

Professor Roberto Jamora delivers an Artist Talk at the Muscarelle Museum. Jamora's talk highlights his

Professor Andrea Wright shares her latest research findings at an APIA Faculty Banh Mi Lecture after being honored as the first recipient of the Jinlan Liu Faculty Research Award. Photo taken by Mitchel Khim '22.

Emmyaward-winningfilmmakerMarissaAroyvisits campustodocumentthehistoryandexperienceof AsiansatWilliam&Mary,workingalongsideWilliam& Mary'sDirectorofVideo&MultimediaLisaCrawford. PhotocourtesyofFrancisTanglaoAguas

Quan Chau '21 performs a personal rendition of "I Can Go the Distance" by Michael Bolton, a centerpiece of the Disney film Hercules. Photo taken by Vivian Hoang '24.

The Asian Centennial at W&M unveils Professor Roberto Jamora's artwork, "VOLUMES." This piece is inspired by the activism and leadership of APIMSW students at W&M. Photo taken by Vivian Hoang '24.

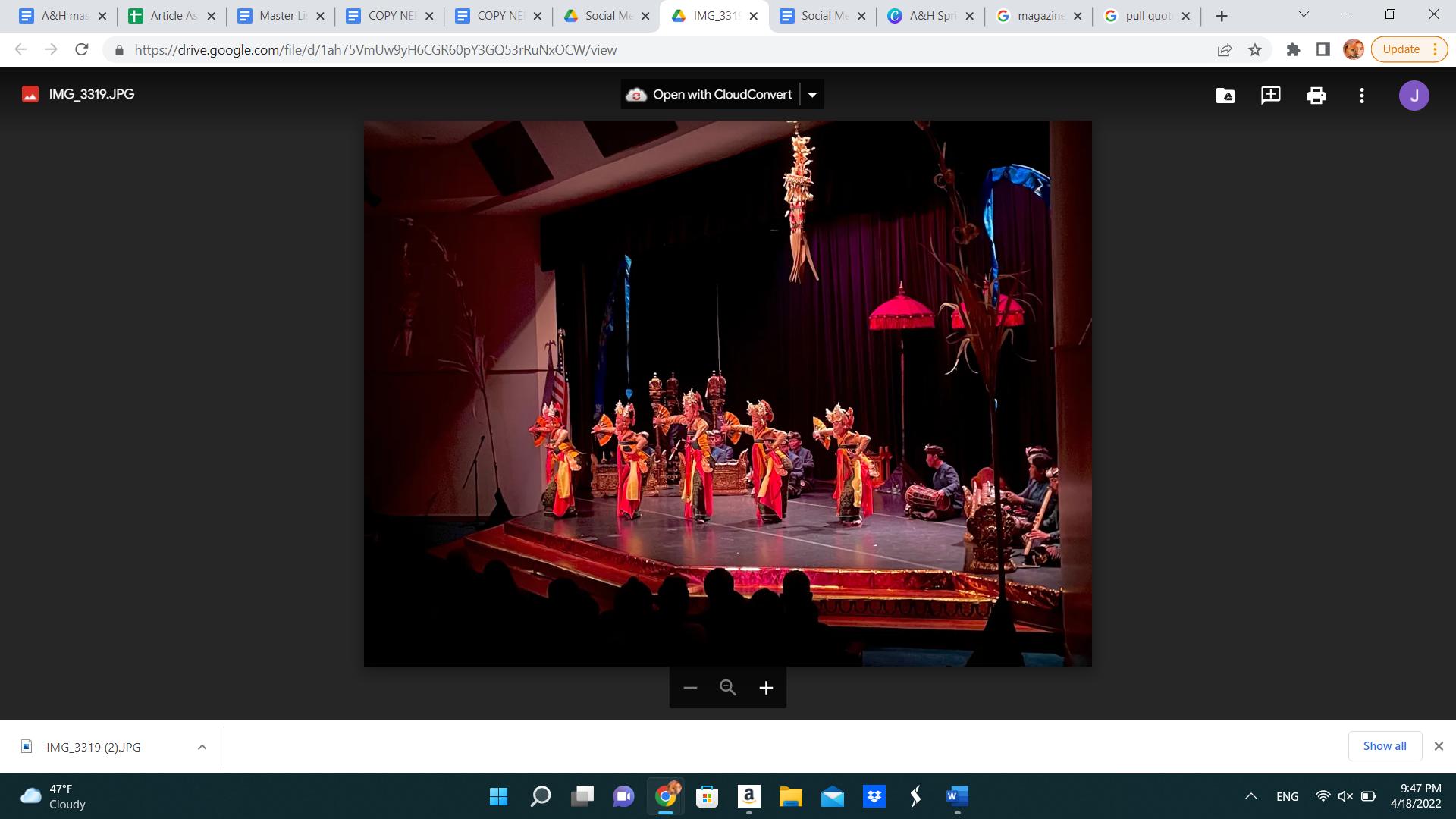

Ameya King '12 performs a traditional Kuchipudi dance at the Asian Centennial Gala. Photo taken by Vivian Hoang '24.

AsianCentennialEvents

At the Asian Centennial Ball, William & Mary's Griffin Bhangra Team delivers an electric performance of a

The Filipino American Student Association (FASA) performs tinikling, a traditional Philippine dance, at the Asian Centennial Ball. Photo taken by Monica Bagnoli '25.

Camille Zeraat, president of FASA and Director of the Asian Centennial Ball, delivers a speech. Photo taken by Monica Bagnoli '25.

Pulitzer Prize winning author Viet Thanh Nguyen visits W&M to receive the Hatsuye Yamasaki '37 Prize for Visionary Leadership. Dr. Nguyen also delivers the 2022 McSwain-Walker Lecture with his talk, "Refugees, Language, and the Meaning of 'America.'" Photo taken by Justin Sherlock.

President Katherine Rowe, unveils a new Virginia Historical Highway Marker honoring Arthur "Art" Azo Matsu '27 in front of the Arthur A. Matsu Arcade in Zable Stadium at William & Mary. This event took place on the April 30th, 2022 — Matsu's 118th birthday and Asian Centennial Day. Rowe is joined by Zack Hoisington, Matsu's great-grandson.

Photo taken by Ryan Goodman '25.

This new Virginia Historical Highway Marker honors Arthur "Art" Azo Matsu '27. Matsu was the quarterback for Tribe football in 1923 and went on to become the first player of Japanese descent in the National Football League. Photo taken by Ryan Goodman '25.

At the Asian Centennial Ball, William & Mary's Griffin Bhangra Team delivers an electric performance of a

The Filipino American Student Association (FASA) performs tinikling, a traditional Philippine dance, at the Asian Centennial Ball. Photo taken by Monica Bagnoli '25.

Camille Zeraat, president of FASA and Director of the Asian Centennial Ball, delivers a speech. Photo taken by Monica Bagnoli '25.

Pulitzer Prize winning author Viet Thanh Nguyen visits W&M to receive the Hatsuye Yamasaki '37 Prize for Visionary Leadership. Dr. Nguyen also delivers the 2022 McSwain-Walker Lecture with his talk, "Refugees, Language, and the Meaning of 'America.'" Photo taken by Justin Sherlock.

President Katherine Rowe, unveils a new Virginia Historical Highway Marker honoring Arthur "Art" Azo Matsu '27 in front of the Arthur A. Matsu Arcade in Zable Stadium at William & Mary. This event took place on the April 30th, 2022 — Matsu's 118th birthday and Asian Centennial Day. Rowe is joined by Zack Hoisington, Matsu's great-grandson.

Photo taken by Ryan Goodman '25.

This new Virginia Historical Highway Marker honors Arthur "Art" Azo Matsu '27. Matsu was the quarterback for Tribe football in 1923 and went on to become the first player of Japanese descent in the National Football League. Photo taken by Ryan Goodman '25.

Photos courtesy of A&H

photographyteam

Photos courtesy of A&H

photographyteam

Oct.7,2021

By: Sumié Yotsukura '22

For attending a school with one of the longest histories in the United States, I had never thought much at all about the history of people like me Asian Americans, that is at William & Mary until around a year ago

The university has always boasted its wealth of (white) alumni contributors to (and throughout) American history and, being half white myself, I’d always embraced that as my inheritance. I’d thought little of my other half and what rich legacy the Asian side of myself might have to inherit and continue at William & Mary.

Such a mindset is not a surprising one. Asian Americans have long been erased from American history, in no small part because of the “perpetual foreigner” stereotype wherein Asian Americans, regardless of their generational history in the U.S., are perceived as outsiders and continually unassimilable into the predominantly white, Anglo-Saxon culture of the U.S. As children, we’re taught very little about the history and contributions of Asian Americans to this country, and indeed, like with object permanence, if we don’t see and learn about something, it might as well not exist.

It was my introduction to the Asian & Pacific Islander American program that made me begin to realize just how much I, like many others, had never even begun to think about these issues,

simply because we were never told to do so. The program takes a great deal of initiative to shine a light on underrepresented faces and voices of the university I knew the names Art Matsu and Hatsuye Yamasaki, the two earliest known Asian American alumni of the university, practically as soon as I began to become acquainted with the program.

As soon as I connected with one student or professor in the program, I’d be pointed in the direction of at least five more Asian Americans at the university to observe and learn from.

For attending a school with one of the longest histories in the United States, I had never thought much at all about the history of people like me Asian Americans, that is at William & Mary until around a year ago

In February 2021, Deenesh Sohoni, sociology professor and director of the Asian and Pacific Islander American studies program, reached out to me to talk about a potential research opportunity what would come to be known as the Asian Pacific Islander Middle Eastern (APM) Research Project.

AsianCentennialEvent

Sumié Yotsukura '22 and Brian Zhao '23 help set up the P K Chen Exhibit, where their original research is published, in Earl Gregg Swem Library Photo courtesy of A&H photography team

Under his guidance and the assistance of Swem Library’s Special Collections librarians and other APIA professors, fellow student researcher Brian Zhao ’23 and I conducted archival research to investigate the lives of the first students of Asian ancestry at William & Mary. Our goal was to bring into public knowledge previously unknown information about the lived history of the first students of color at our institution.

While on assignment for the APM Research Project, I found myself sitting in the tranquil wood-paneled reading room of Swem’s Special Collections on a quiet Friday in early spring 2021, fingers twitching in anxious anticipation. After a few minutes, the research librarian on call emerged, a box of old, worn documents in hand. She laid out a thick foam mat and a long, weighted roll wrapped in blue velvet. Then, ever so gently, she pulled out one thin, bound booklet of aged cream-colored paper a volume of The William and Mary Literary Magazine, dated from “FEBRUARY, 1923” in large lettering and placed it on the mat

At the top of the teaser table of contents on the cover: “A CHINESE STUDENT’S FIRST IMPRESSIONS OF AMERICA By P. K. Chen.”

I delicately opened to the first couple of pages, carefully draping the blue roll along the edges to hold the booklet open, and began to read with wide eyes the selfrecorded story of a young Chinese student’s journey from Beijing, China to Williamsburg, Virginia, where he would become the first recorded student of Asian ancestry to ever attend the College of William & Mary. Pu Kao Chen arrived from China to study here at W&M in 1921, 100 years ago, and I could not believe my luck in finding this complete record, in his own words, of his experience of that arrival. His article painted a picture of his trip over, depicting both his wonder and excitement at the U.S., as well as the xenophobic, racist prejudice he immediately encountered here

My very assignment had been to research P.K. Chen and the racial climate he entered when he studied at William & Mary by digging through archival fragments; here, no mere fragment, but a complete, in-depth account had fallen into my lap written by the man himself addressing that very topic. Further, never before had I felt such solidarity with someone from the annals of history.

I realized that he was writing “A Chinese Student’s First Impressions of America” in much the same way I am writing this article now: a 20-something soon-to-be graduate getting their experiences on paper so that hopefully, they may make a statement about the racial prejudices and injustices faced in their time, mobilizing readers to do something about it and learn how to better understand the other people they share space with.

P.K. Chen’s story ultimately unlocked the creation of the exhibit. Professor Sohoni had suggested that I take advantage of my background in theatre and create an exhibit With every bit of archival material I had read through, the world and racial climate of Williamsburg, VA, circa 1921, came that much more clearly and closely into view. That archival research, the discovery of P.K. Chen’s firsthand account, and my assignment came together in my brain and clicked: the bulk of his narrative followed his travels from location to location, map-like in its maneuvers, so what better way to present his story than a spatial recreation of that map? I would visually retell P.K. Chen’s story by using his own vivid and illustrative narrative and providing the context necessary to understand what he had written about his experiences

Yotsukura '22 and Zhao '23 work with Prof Deenesh Sohoni, APIA program director and Asian Centennial co-chair, to put the finishing touches on the exhibit

Photo courtesy of A&H photography team

Yotsukura '22 and Zhao '23 work with Prof Deenesh Sohoni, APIA program director and Asian Centennial co-chair, to put the finishing touches on the exhibit

Photo courtesy of A&H photography team

From April to August, the exhibit fell into place. I set about examining P.K. Chen’s article with a fine-toothed comb to identify where the piece provided windows into key historical, legal, and sociological moments of the time I looked for where I might be able to further vivify with photographs, charts, and maps Chen’s already vibrant illustrations of the America The whole team had been scouring old issues of the Flat Hat newspaper and the Colonial Echo for indications of the early 20’s racial climate at W&M, and boy, did it come in handy. A number of fragments disclosing white nationalist club establishments, celebrated visits from the creator of the most archetypal racist film Birth of a Nation, and jokes ingrained with the casual racism of the time would make their way into the panels to paint ever more clearly a portrait of what exactly Williamsburg must have appeared as to an Asian man 100 years ago.

Our team of researchers and archivists gathered relevant contextual information, wrote blurbs, and went in search of relevant historical images and records to display as visual context aids For the panel illustrating Chen’s first steps onto American soil in San Francisco, our archivists managed to find images of the actual record he signed upon arrival on Angel Island, along with a whole slew of vivid images in striking clarity of locations from the ports in Shanghai to the Golden Gate Bridge

In its completed form, the P.K. Chen exhibit takes its visitors on his journey from China to Williamsburg. At every stop, you read his words, you see bits and pieces of what he saw, and you have the chance to learn and understand exactly how broader historical developments at the time affected this one Chinese international student personally. Through this exhibit, we are able to place the person back in the history.

Photo Courtesy of W&M Libraries

Photo Courtesy of W&M Libraries

P

h o t o C o u r t e s y o f W & M L i b r a r i e s

This personalization of the history, in which we identify how history was viewed in its time by a real person with authentic and unique experiences, is what helps us connect and empathize with these students who might otherwise seem distant from us here in the present. Far too often, we accept, and to some extent, dismiss the awful racism and discrimination faced by those who came before us in history as a consequence of their being a part of history; it can be all too easy to forget that these seemingly distant historical figures were just as human as we are today. Racism was no more acceptable or bearable an experience for them then than it is for us. By experiencing P.K. Chen’s experience of history, that history, and its consequences in its time, become that much more real and true to us.

For Professor Francis Tanglao Aguas, founder of the APIA program and cochair of the Asian Centennial, this sentiment could not be more central to APIA & the Asian Centennial’s efforts.

"When [P. K. Chen] was called ‘Chinaman’ in 1921, he did not say to himself, ‘What do I expect, it's 1921,’” Aguas said of Chen’s account. “It hurt him deeply 100 years ago."

Unfortunately, the experiences that Chen talks of do still ring so true today: with the rise in anti-Asian sentiment and violence during the COVID-19 pandemic, Chen’s struggle with facing the anti-Asian slurs and prejudices sent his way don’t seem particularly far in the past While it is depressing, it is absolutely crucial that we see nothing has changed

If we see that nothing has changed in the last 100 years, perhaps it will spur us to take further steps to ensure that 100 years from now, anti-Asian slurs will seem unsightly relics of a time long ago. If we continue to do this work, we can make it so that 100 years from now, freshmen may well arrive at William & Mary already well-aware of its rich history of APM alumni and their contributions, 200 years strong.

Racism was no more acceptable or bearable an experience for them then than it is for us

P h o t o s c o u r t e s y o f W & M L i b r a r i e s

Oct.8,2021

In a virtual visit to William & Mary, Russell Jeung hosted keynote lecture on combating anti-Asian hate and racism as a whole.

BY: AIDAN LOWE '23

BY: AIDAN LOWE '23

Oct. 8, 2021, Russell Jeung, a sociologist at San Francisco State University, founder of Stop Asian Hate, and renowned author delivered the lecture, "History, Causality, and Resistance: Stopping Anti-Asian Hatred during COVID" over Zoom. Viewings of the lecture were held in Sadler Center's Commonwealth auditorium Throughout the talk, Jeung explored complex geopolitical topics to break down the fundamental components of the #StopAsianHate movement, which began in response to the sharp increase in discrimination against Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the necessity of these social justice movements in espousing tangible change

Jeong provides nationwide reports and anecdotes of AAPI people’s lived experiences with discrimination, historical roots of racial discrimination within immigration policies analysis, and the Asian American community’s adamant resistance against oppression Jeung cites over 9,000 examples of discrimination, including verbal harassment, name-calling, shunning, physical assault, coughed or spat upon, etc. Furthermore, Jeung reveals over 70% of youth reported seeing "demeaning, racist, or offensive" material online over the last month, vicariously experiencing the physical manifestation of discrimination other members have gone through.

"JEUNG REVEALS OVER 70% "JEUNG REVEALS OVER 70% OF YOUTH REPORTED SEEING OF YOUTH REPORTED SEEING "DEMEANING, RACIST, OR "DEMEANING, RACIST, OR OFFENSIVE" MATERIAL ONLINE OFFENSIVE" MATERIAL ONLINE OVER THE LAST MONTH, OVER THE LAST MONTH, VICARIOUSLY EXPERIENCING VICARIOUSLY EXPERIENCING THE PHYSICAL THE PHYSICAL MANIFESTATION OF MANIFESTATION OF DISCRIMINATION OTHER DISCRIMINATION OTHER MEMBERS HAVE GONE MEMBERS HAVE GONE THROUGH " THROUGH "

However, the hard numbers provided by such statistical data cannot accurately represent the lived experiences Asian Americans have gone through. Jeung stresses the importance of analyzing the creation of anti-Asian hate movements, or even anti-racist movements in general, as it is vital to examine the lived experiences of racism within minority populations and understand the historical roots from which these perspectives may come. While anecdotes and statistics may provide valuable information on current nationwide trends, they do not comprehensively convey important information on the complex origins of racism

The message of "cognitive liberation" and the founding of anti-racist movements that Jeung promotes is paramount to increasing the awareness of the struggles and discrimination the community faces daily.

AsianCentennialEvent

Photo taken by Mitchel Khim '22

Oct.12,2021

Tuesday, Oct. 12 and Wednesday, Oct. 13, Colonial Williamsburg welcomed awardwinning West Coast-based actress, educator, director, and activist Rinabeth Apostol to Kimball Theatre.

Over the course of two days, Apostol gave a moving solo performance about her experience with the nature of womanhood and relationship with her sexuality as a brown woman in America.

As Apostol approached the audience at the start of the show, she expeditiously caught the viewer’s attention Using theatre as a platform through which she connects to and shares her unique experiences, Apostol made “little brown gIRL” stand out as an emotional masterpiece.

Throughout the play, Apostol appeared fixated on the passage of time The performance largely took the form of a memoir, chronicling events in her life in a linear fashion. Using story, song, and raw humor, Apostol walked through her lifelong journey of coming into her own as a proud lesbian Filipina actress in America

Punctuated throughout her retelling of her life were Apostol’s requests that the audience “GTS” (google that shit), generally when she referenced a cultural relic she feared is no longer relevant or mainstream lingo that “boomers” are unfamiliar with.

Starting the story of the “little brown gIRL,” Apostol highlighted age seven as a critical turning point in her life at which she’d ‘learned everything.’ Putting that claim to the test, Apostol then recited four, very personal anecdotes of her encounters from that time

At the age of seven, a “melanin deficient” girl telling young Apostol that she was too brown to be Wendy in her ballet class’ production of “Peter Pan” simultaneously crushed her dreams and allowed Apostol to realize how proud she was of her brownness.

Apostol also opened up about the sexual assault and betrayal of trust from a family member that she experienced at this age. Describing her pain and frustration with the audience through rhyme and reason, Apostol then characterized her existential crisis on the basis of her sexuality.

In a funny, captivating, and lighthearted reflection, Apostol gave the audience a glimpse of her first lesbian crush As the crowd laughed and sat in awe of Apostol’s sentiments, they lived vicariously through her words and ultimately her performance.

AsianCentennialEvent

Rinabeth Apostol in "little brown gIRL"

Photo taken by Aidan Lowe 23

Apostol made "little brown girl" stand out as an emotional masterpiece.

B Y : M Y R A S I M B U L A N ' 2 5

As Apostol wove us through her big moments in life, she touched on one that significantly impacted her as an actress

When offered her first debut role in a well-known blockbuster comedy, Apostol found herself at a crossroads Was she to attain her childhood dream of being a Hollywood star at the expense of autonomy over her body, or was she to stand firm in her morals and reject playing an overly sexualized character, thus sacrificing her dream?

Through engaging the audience in an emotional song that passionately ended with not only Apostol’s tears, but the audience’s as well, the young actress conveyed her respect for herself and her morals

By taking the courageous leap towards self-love by prioritizing herself, Apostol’s manager dropped her, making her a freeagent actress. However, with the advent of the coronavirus pandemic, Apostol, a once thriving actress, was unable to find work as the world was put on pause.

Apostol, along with everyone else who was homebound for months, was going crazy upon being isolated with nothing else but her own thoughts. However, Apostol expressed that social media and news media became her savior during these trying times.

However, one reservation Apostol has with social media is the fear of becoming out of touch with rapidly evolving cultural references and thus unable to communicate, especially with the advent of mass media and its influence on our vernacular.

The audience was moved by the closing scene, as Apostol wrapped the performance with a poignant question: “why was I spared?”

Not understanding why the fight for equality for race, sexuality, and gender is still being fought, Apostol emphasized how she and her Asian brothers and sisters all walk with a target on their backs each day

Apostol took symbolic alcoholic shots representing the lives of the six Asian women whose lives were taken during the Atlanta spa shooting in March 2021, shedding light on the intolerance AAPI individuals face in this country Ending the scene by downing six striking shots, Apostol dedicated each shot towards every reason she routinely fights for survival in a country marked by racial violence.

Though an undercurrent of anxiety ran throughout the performance, and Apostol warned of the consequences of parading proud, Apostol concluded by claiming pride in her journey and who she is today. By the end of the show, Apostol has finally felt a little more grown up.

P

t

t

k e n b y A i d a n L o w e 2 3

From left to right: Francis Tanglao Aguas, Veronica Salcedo 02, Dionne Paniza, and Rinabeth Apostol pose for a photograph following the production of little brown gIRL

h o

o

a

Using story, song, and raw humor, Apostol walked through her lifelong journey of coming into her own as a proud lesbian Filipina actress in America.

"Why was i spared?"

AsianCentennialEvent

Oct.15,2021

ARETROSPECTIVEONASIAN ARETROSPECTIVEONASIAN AMERICANIDENTITY AMERICANIDENTITY

STRIVING FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE THROUGH BELONGING AND LIBERATION

BY: RAYNA YU '21

""THIS THIS ATMOSPHERE ATMOSPHERE OF EXCLUSION OF EXCLUSION BIRTHED THE BIRTHED THE IDEA OF ASIAN IDEA OF ASIAN AMERICANS AS AMERICANS AS PERPETUAL PERPETUAL FOREIGNERS FOREIGNERS THOSE WHO THOSE WHO NEVER QUITE NEVER QUITE BELONG IN BELONG IN AMERICA " AMERICA "

“THE IRONY, OF “THE IRONY, OF COURSE, IS THAT COURSE, IS THAT A RACIST A RACIST STEREOTYPE, THE STEREOTYPE, THE MODEL MINORITY, MODEL MINORITY, HAD TO BE HAD TO BE CREATED IN CREATED IN ORDER TO ORDER TO ‘DEBUNK' RACISM ‘DEBUNK' RACISM AGAINST AGAINST AFRICAN AFRICAN AMERICANS AND AMERICANS AND OTHER NON OTHER NON WHITE WHITE AMERICANS ” AMERICANS ”

FRIENDSHIPSFORGED FRIENDSHIPSFORGED THROUGHARABICMUSIC THROUGHARABICMUSIC

JOHNNY FARRAJ AND THE MIDDLE EASTERN MUSIC ENSEMBLE JOHNNY FARRAJ AND THE MIDDLE EASTERN MUSIC ENSEMBLE

With over-capacity attendance at Ewell Recital Hall in the heart of campus, William & Mary’s Middle Eastern Music Ensemble was joined by guest artist Johnny Farraj to grace many ears with the tunes of West Asia Though the concert was held on the chilly night of Nov 12, 2021, the venue was warmed by the community’s celebration of Middle Eastern stories and cultures.

Born in Lebanon and of Palestanian descent, Farraj triumphs through life as he balances his roles simultaneously as a distinguished musician and a software engineer Farraj was welcomed to William and Mary by his long time friend Anne Rasmussen, a music and ethnomusicology professor at the university. This was actually his second attempt to visit the university; the first would have been for the “Songs for Syria'' concert in March 2020, but it was cancelled due to the pandemic.

After multiple Zoom rehearsals and virtual ensemble productions, Farraj was finally able to join the Middle Eastern Music Ensemble in person, with the added benefit of having Professor Rasmussen as a director. The ensemble has also worked with other scholars and guest artists in similar events, seeking to honor the study and performance of traditional sounds and musical theories from the Middle East and the Arab World The ensemble was delighted to add Farraj to the indispensable network of friendships

BY: EDDIE CHOI 22

Common topics like love and nature are melodically expressed through Middle Eastern storytelling. Common topics like love and nature are melodically expressed through Middle Eastern storytelling It was a powerful reminder that no matter how everyone’s experiences differ, humans can find a way to connect through their ability to follow the flow of life. One may perceive the world through a particular lens, but everybody has an equal body behind that lens.

Though the concert was Though the concert was held on a chilly night, the held on a chilly night, the venue was warmed by the venue was warmed by the community’s celebration community’s celebration of Middle Eastern stories of Middle Eastern stories and cultures and cultures

Though he hopes this is not his last visit, Farraj has thankfully left some unmissable traces through which the public can find him. He is the creator of MaqamWorld, the leading online reference on Arabic music theory that is now translated into 8 languages. He also co-authored “Inside Arabic Music” along with colleague Sami Abu Shumays, and intends to keep serving as an advocate and educator on the matter Until his next visit, William & Mary eagerly awaits Farraj's return

AsianCentennialEvent Nov.12,2021

Courtesy Photo from W&M Libraries

Nov. 30, 2021

AN ARTISTIC REPRESENTATION OF ASIAN PACIFIC MIDDLE EASTERN RESILIENCE AT WILLIAM & MARY

BY: EDDIE CHOI '22 & CALVIN KIM '22

"LOCAL."

This is the very word the Asian Centennial Co-Chair Francis Tanglao Aguas used to explain the reasoning behind the designation of Roberto Jamora as the inaugural Asian Centennial Distinguished Fine Arts Fellow.

Both an adjunct lecturer of APIA studies at William & Mary and assistant professor of fine arts at VCUarts, the Filipino-American artist and educator was born and raised in Virginia Beach and is currently based in Richmond, Virginia.

In an emotional account of his life journey, Jamora shared his personal and artistic development during his multiple relocations before returning home to Virginia Jamora learned to conceptualize the beauty of color something that serves as an integral part of his work and is held close to his heart. To Jamora, colors hold immense power and can ceaselessly inspire, especially in regard to the discourse of people and cultures They show the skin tones of those he loves dearly, the shades of clothing on his wife from a favorite memory, and even the luminescence brought upon by nature.

This kind of power, as Jamora reveals, is what he aims to bring to APIM individuals through artistic expression, a responsibility he does not take lightly Ever since his appointment as the Arts Fellow for the Asian Centennial, Jamora has dedicated much of his time and efforts to

researching how he can successfully achieve this goal, even looking into water bodies and flowers from different parts of Asia.

Another aspect of “Asianness” Jamora sought to highlight was versatility, contrary to what society says it should be Jamora asserted that the "bigotry" described in Pu Kao Chen '23’s essay from over a hundred years ago is still commonly experienced by not only Asian Americans, but also the BIPOC community as a whole. A victim himself, Jamora now has the chance to tackle this issue with his own artwork

AsianCentennialEvent

Pictured to the right: Roberto Jamora, speaking about his vision for the Centennial commemoration piece at the Muscarelle Museum of Art at William & Mary on Sept 29, 2021

TO JAMORA, COLORS HOLD IMMENSE POWER AND CAN CEASELESSLY INSPIRE, ESPECIALLY IN REGARD TO THE DISCOURSE OF PEOPLE AND CULTURES

P h o t o t a k e n b y E d d i e C h o i 2 2

“[Pu Kao Chen’s essay] was inspiring on an artistic and personal level to learn about the early Asian students, what they faced and overcame. I felt called to make something that alluded to power, joy, and reflecting on the past,” revealed Jamora.

All this brought Jamora to the recurring theme of multiethnic coalition building Jamora recognizes the value in working together to fight for a unified cause: representation and inclusion

“My biggest tip is to build the coalition This is not a 'we are the world' approach to social change for the liberation of BIPOC folks, but an acknowledgment of both differences and shared experiences," Jamora said "We need to nurture, show up for, and support the creative callings and curiosities of our community. This is healing work, and healed people heal people."

Jamora also investigated critical questions on diversity, hammering home the point that inclusion must encompass material gains to be beyond performative.

"As more institutions throughout the world and specifically in this country see diversity as a strength, and BIPOC folks are offered a seat at the table, we need to also ask if there is a plate of food waiting for us at the table," Jamora said. "In other words, are we given the resources to succeed when we are included? And if so, what can we share with others?"

Such eloquence was not only present in Jamora’s words, but also in his Centennial piece which he showcased during the Muscarelle APIM Print Art Unveiling on Nov. 30, 2021. Though Jamora humbly stated he was "just making a couple pieces of art" compared to the other Centennial guests

and performers, his painting said otherwise Titled “Confluence,“ the piece left attendees awestruck even through their Zoom screens

“One adjective I would use to describe this piece is dynamic," Jamora said "In my first piece for my Asian Centennial Fellowship, I created a composition with forms that allude to time and change The Asian, Pacific Islander, and South West Asian community is so beautifully diverse with histories that intersect, hence the title of the piece, 'Confluence.' It’s about a lot of experiences coming together."

P h o t o s t a k e n b y E d d i e C h o i ' 2 2

Pictured above is Jamora's Asian Centennial centerpiece, "Confluence," available for public viewing at the Muscarelle Museum of Art in Williamsburg, Virginia

Jamora and Muscarelles Director of Engagement and Distinguished Artist in Residence Steve Prince lead "The Voice of the Artist" vision talk at the Sheridan Gallery in the Muscarelle Museum of Art on September 28, 2021

In addition to its dynamism, Jamora highlighted the piece's acknowledgement of the diverse cultural heritages that make up the Asian diaspora.

"In celebrating the first hundred years of Asian students at William & Mary, I believed it would be important to highlight some of the early Asian students, the land, and waterways as a metaphor for migration, movement, connection, and coalition building,” Jamora said

An artistic representation of Asian Pacific Middle Eastern resilience at the university, Jamora’s Centennial piece can be found at the Muscarelle Museum of Art. As for the arts fellow himself, Jamora is already pursuing research on additional pertinent subjects into which he has yet to delve, which will culminate in the form of his next mixed-media piece to be released this upcoming spring. The public can additionally look for Jamora and his projects on his self-titled website: robertojamora.com.

"WE NEED TO NURTURE, SHOW UP FOR, AND SUPPORT THE CREATIVE CALLINGS AND CURIOSITIES OF OUR COMMUNITY. THIS IS HEALING WORK, AND HEALED PEOPLE HEAL PEOPLE."

Art as a collaborative endeavor: Jamora invites Professor Tanglao Aguas (pictured top left) and students from APIA 380: Media, Agency, and Mobilization to partake in the creative process of producing prints like "Confluence " Photos courtesy of Myra Simbulan 25 Behind the scenes: Pictured bottom left and bottom right is documentation of the physical undertaking behind the creation of "Confluence." Jamora works with one of his students to mix the different shades of skin tones within "Confluence" in order to represent coalition building across the BIPOC community Photos Courtesy of William & Mary

The Asian Centennial Committee founded the W&M Asian Centennial Awards to recognize William & Mary alumni who have advocated for others through their careers and their volunteer efforts The inaugural awardees of the Asian Centennial Awards are leaders and change-makers just like our earlier students of Asian descent such as Hatsuye Yamasaki ’37, who despite being the lone woman of color on campus was the president of Brown Hall, William & Mary’s dormitory for women.

By: Francis Tanglao Aguas

The inaugural W&M Asian Centenn Awardees are Michael Chu J D ’92, Pall Rudraraju ’17, Amandeep Sidhu ’00, Yiq “Pocket” Sun ’13 and David Uy ’93, M.B.A. ’96

Chu and Sidhu are both lawyers who w pro-bono to support important causes their communities. Chu worked for ma years on the board of Asian America Advancing Justice in Chicago.

Sidhu co-founded the Sikh Coalition, the largest civic organization for Sikhs in the US Rudraraju, the youngest of the awardees, was recognized for their work with the Human Rights Campaign Uy is founder of the Chinese American Museum in DC, and Sun is a global change-maker who empowers women in business.

For the community award, the former student leaders of FACES, led by Judith Chaisiri Lee ’00 and Veronica Salcedo ’02 were recognized for their sustained efforts in elevating the visibility of the Asian American community at W&M from 1999 to 2003, which was capped off with a symposium for which they received a grant from the Commonwealth of Virginia

The inaugural winners of the Asian Centennial Awards are exemplars to the global W&M community of how we can serve and embrace those in our communities who have been marginalized or ignored, especially in the time of COVID-19 and conflict.

More than 30 nominations were received by the Asian Centennial Committee for consideration, reflecting the diverse fields where alumni of Asian Pacific Islander, and Middle Eastern/South West Asian descent pursue their agency

The awards were presented by Provost Peggy Agouris at the Masquerade at the Muscarelle, a gala fundraiser for the Asian Pacific Middle Eastern Project Fund, and the recipients each received a special citation from W&M President Katherine Rowe.

AsianCentennialEvent

'24

PhototakenbyVivianHoang

Inaugural W&M Asian Centennial Awards recognize notable alumni during Masquerade at the Muscarelle, an Asian Centennial gala fundraiser

April30,2022

Michael Chu J.D. 92 accepts his W&M Asian Centennial award from Provost Peggy Agouris

Amandeep Sidhu ’00 smiles for a photo alongside Provost Peggy Agouris and Prof Berhanu Abegaz after accepting his W&M Asian Centennial award

PhototakenbyVivianHoang24

Upon receiving a W&M Asian Centennial award, Veronica Salcedo 02 delivers an acceptance speech on behalf of FACES

P hoto taken byVivianHoang'24

PhotoscourtesyofRhademMusawah

IgnitingChange throughFilmmaking

AConversationwithRhademMusawah

BY: RAYNA YU '21

AConversationwithRhademMusawah

BY: RAYNA YU '21

Underneath his easygoing personality lies a fiercely committed advocate of social change

PROFILES

MUSAWAH'S work focuses on bridging the divide between LGBTQ+ and Muslim communities, both of which he belongs to

“I'm quite privileged I have not been red tagged yet by the government,” Musawah said “I don’t want to be in that position because a dead activist cannot make any change.”

The path of an activist isn’t easy, but Musawah will walk it to the end.

PhotoscourtesyofRhademMusawah

BY: EMILY KEY '23

PhotoscourtesyofRhademMusawah

BY: EMILY KEY '23

EARL CARR ’01 HAS EARL CARR ’01 HAS BEEN BUSY BREAKING BEEN BUSY BREAKING BARRIERS IN THE BARRIERS IN THE WORLD OF FINANCE WORLD OF FINANCE AND INTERNATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL POLITICS POLITICS

PROFILES - APIA ALUMNI

ALTHOUGH CARR ALTHOUGH CARR GRADUATED 20 GRADUATED 20 YEARS AGO, HE YEARS AGO, HE STILL HOLDS ON TO STILL HOLDS ON TO WHAT MADE WHAT MADE ATTENDING ATTENDING WILLIAM & MARY WILLIAM & MARY A VALUABLE A VALUABLE EXPERIENCE EXPERIENCE.

ThriceBlessed: ThriceBlessed:

ProfessorChinuaThelwell’s ProfessorChinuaThelwell’s ExtraordinaryYear ExtraordinaryYear

BY: MEY SEEN ‘23

BY: MEY SEEN ‘23

This year cannot be adequately apportioned into words Not ten, not a hundred, not nine hundred. Yet it can neither be ignored nor understated. Professor Chinua Akimaro Thelwell did neither

This past spring, I took Asian Pacific American History with Thelwell, an associate professor of history and Africana studies and a core faculty member of the Asian & Pacific Islander American Studies program Sitting through the first class, there was already something about him that I respected. Perhaps it was the way he spoke almost lost in thought but evidently intentional I hadn’t yet noticed the absence of authoritative assertion that normally accompanies a classroom. Rather, Thelwell filled the room with the sensation of being heard, understood, and seen.

Every personal anecdote was met with immediate empathy: “I’m sorry that you went through that,” and "That must have been an incredible experience.” Every story was counted, every story was important, and no experience was minimized regardless of the degree.

During class, there was no glossing over politics for the sake of neutrality or avoiding conflict. APIA history was intimately intertwined with critical race theory, which inevitably led to discussions of the current social climate It brought me comfort and gave me a sense of safety to come into a class in which the realities of modern white supremacy were acknowledged In this fragile climate, most are hesitant to discuss certain controversial subjects, yet Thelwell had the courage to unashamedly address the problems that people like me face.

Thelwell's lectures inspired mobilization Discussions of discrimination against Asian Pacific Islander Americans and coalition-building between communities of color were not simply factual; they were reminders that people fought for us to be visible and have an undeniable claim in this country They were assertions that we belong. They were recognitions that no change is ever enacted with complacency and inaction; we must cause the change today, tomorrow, and every day thereafter Thelwell instilled in me the knowledge that I can be more and that there are others who will join me in the fight for our community.

Photo courtesy of Emily Wilcox

PROFILES - APIA FACULTY

THELWELL FILLED THE THELWELL FILLED THE ROOM WITH THE ROOM WITH THE SENSATION OF BEING SENSATION OF BEING HEARD, UNDERSTOOD, HEARD, UNDERSTOOD, AND SEEN AND SEEN

When COVID-19 took over, Thelwell became a source of strength At the time, there seemed to only be a few who knew how to react and operate during a major national crisis. People's first inclination seemed to be to simulate normality, which did not work Instead, Thelwell opened every class with a check-in on students and sharing of good news and energy. However, he made sure to recognize the gravity of the situations we face. It was hard to be okay this year, but Thelwell made me feel okay to not be okay

What’s truly noble is that Thelwell exhibited such constant concern for his students and emphasized the wellbeing of greater society during what has been a year filled with his own blessings Thelwell had three major life dreams realized in a single year: publishing his book, achieving tenure, and getting married.

“Publishing a book has been a long-time dream of mine," Thelwell said "Ever since I was a college student, I dreamt of a future day when my book first arrives in the mail."

His book, "Exporting Jim Crow: Blackface Minstrelsy in South Africa and Beyond," discusses anti-Black imagery as a global problem that was caused by the exportation of racist American popular culture around the world. Thelwell asserts that “because anti-Black racism is a global problem, anti-racist thinking also has to be global ”

Imagine working toward your undergraduate degree twice in a row, but instead of taking notes, you’re planning the lectures, and your senior capstone project is getting published. On top of all of that, you're getting assessed by an entire panel of your peers. There is no question that Thelwell has earned his accolades through his unceasing dedication to academia, and Thelwell savors every bit of success he has worked for.

“It’s an amazing feeling to turn this long-term goal into a reality," Thelwell gushed "I’m very happy to be tenured after so many years of graduate school, postdoctoral fellowships, and teaching appointments."

For Thelwell, his tenure and publication is especially rewarding as a person of color working in anti-racist scholarship.

"And here’s the best part: I did not compromise," Thelwell said "I got tenure while representing an anti-racist scholarship There are anti-racists and racists; there is nothing in between. People have already chosen sides whether they know it or not.”

Thelwell is also able to enjoy the fruits of his labor with a life partner: Emily Wilcox, who serves as the program director and an associate professor of the Chinese program at William & Mary. The couple serendipitously met at William & Mary years ago, bonded over scholarship, and supported each other through tenure. The pair married the summer of 2021 in a small, sociallydistanced ceremony