8 minute read

HUNOHAKIANS

Founded More thnn A Century Ago to Liberate Armeninns from Ottoman Rule, the Social Democratic Hunclnkian Party Is Now Involved In Strengthening the New Republic of Armenin

pendence could only be achieved through a revolution, while the Ottoman Empire was at war and vulnerable. After Ottoman Armenia was liberated, Russian and Persian Armenia would be freed and socialism established. Eventually oppression would be eliminated throughout the world with the triumph of world socialism.

Advertisement

The party was to be organized in a centralized manner and through propaganda, agitation, and terror (against Turks and

By ABAil ARKUI{ SpediltoAlf,

Armenian traitors) would obtain the participation of the masses in an initial revolution. European intervention could not be relied upon but could be benefitted from.

After 1889, the party had members in the Ottoman Empire, and local members partisan bands to fight such oppressors. When the feudal lords were unable to destroy these bands through their own forces, they called in the local govemment, who sent policemen and soldiers against the partisans. T\e fedayees, as members of these bands were called, would also ob. tain revenue and weapons by robbing govemment resources. They attempted to cooperate with local Muslims in fighting op pressors along class lines, but this strategy had limited success. worked to raise the national consciousness of Armenians. Those working as teachers in Armenian schools, in addition to Armenian history and culture, secretly taught their students to defend themselves and resist local oppressors like Kurdish and Turkish feudal lords, bandits, usurers and corrupt government officials.

The most visible of the pafty's activities in the Ottoman Empire were the demonsrations it organized. They were intended to weaken the authority of the Ottoman govemment and gain the adherence of more Armenians. Despite the fact that in its theoretical writings the party preached avoiding the pitfall of placing its hopes on European intervention, in practice most demonstrations werc primarily intended to obtain European publicity and pressure for Ottoman reforms. The examples of the Balkan states, lrbanon and past Eure. pean accords and declarations concerning Otto man Armenians werc ap parently too much to resist.

Hunchakian members organized armed

Disappointed that the European powers did not attempt to enforce Ottoman reforms after earlier protest and clashes in Garin (Erzerum), the party organized the first Armenian political demonstration to take place in the Ottoman capital of Constantinople on July 27, l&90, At the end of 1892 and the beginning of 1893, in many cities of Armenia Minor and westem Anatolia, placards were posted calling on Ottoman Muslims, with the support of tndian Muslims and the British, to revolt against their sultan as a disgrace to Islam. Aside from European publicity and the raising of Armenian consciousness, these actions led to many arests, the hanging of some revolutionaries, local fights, and even a few small-scale massacres of Armenians.

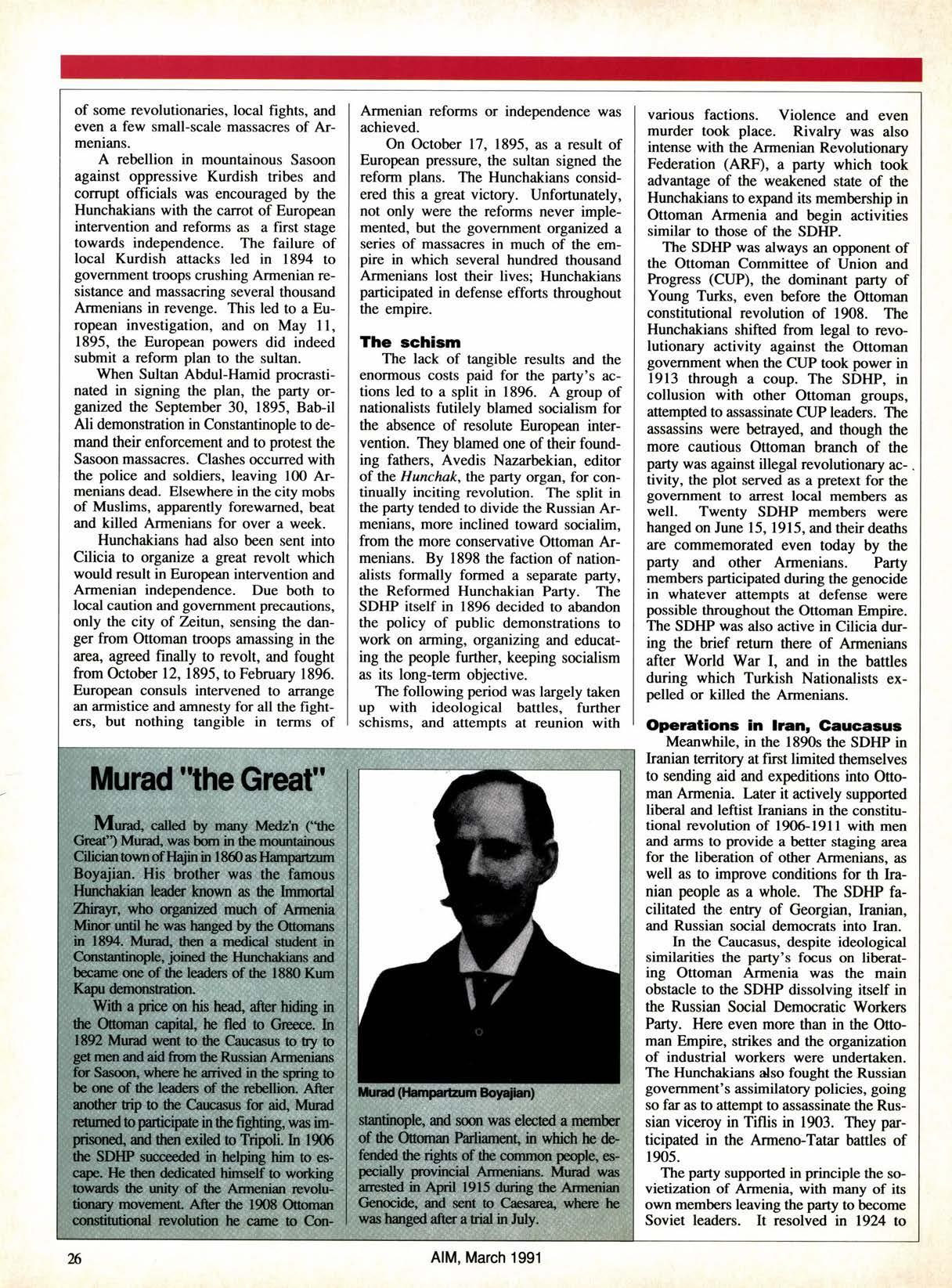

A rebellion in mountainous Sasoon against oppressive Kurdish tribes and corrupt officials was encouraged by the Hunchakians with the carrot of European intervention and reforms as a frst stage towards independence. The failure of local Kurdish attacks led in 1894 to govemment troops crushing Armenian resistance and massacring several thousand Armenians in revenge. This led to a European investigation, and on May ll, 1895, the European powers did indeed submit a reform plan to the sultan.

When Sultan AMul-Hamid procrastinated in signing the plan, the party organized the September 30, 1895, Bab-il Ali demonstration in Constantinople to demand their enforcement and to protest the Sasoon massacres. Clashes occurred with the police and soldiers, leaving 100 Armenians dead. Elsewhere in the city mobs of Muslims, apparently forewarned, beat and killed Armenians for over a week.

Hunchakians had also been sent into Cilicia to organize a great revolt which would result in European intervention and Armenian independence. Due both to local caution and govemment precautions, only the city of 7.eitl'lri, sensing the danger from Ottoman troops amassing in the area, agreed finally to revolt, and fought from October 12,1895, to February 1896. European consuls intervened to arrange an armistice and amnesty for all the fighters, but nothing tangible in terms of

Armenian reforms or independence was achieved.

On October 17, 1895, as a result of European pressure, the sultan signed the reform plans. The Hunchakians considered this a great victory. Unfortunately, not only were the reforms never implemented, but the govemment organized a series of massacres in much of the empire in which several hundred thousand Armenians lost their lives; Hunchakians participated in defense efforts throughout the empire.

The schism

The lack of tangible results and the enonnous costs paid for the parq/'s actions led to a split in 1896. A group of nationalists futilely blamed socialism for the absence of resolute European intervention. They blamed one of their founding fathers, Avedis Nazarbekian, editor of the Hunchak, the party organ, for continually inciting revolution. The split in the party tended to divide the Russian Armenians, more inclined toward socialim, from the more conservative Ottoman Armenians. By 1898 the faction of nationalists formally formed a separate party, the Reformed Hunchakian Party. The SDHP itself in 1896 decided to abandon the policy of public demonstrations to work on arming, organizing and educating the people further, keeping socialism as its long-term objective.

The following period was largely taken up with ideological battles, further schisms, and attempts at reunion with various factions. Violence and even murder took place. Rivalry was also intense with the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARD, a party which took advantage of the weakened state of the Hunchakians to expand its membership in Ottoman Armenia and begin activities similar to those of the SDHP.

The SDHP was always an opponent of the Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), the dominant party of Young Turks, even before the Ottoman constitutional revolution of 1908. The Hunchakians shifted from legal to rev(> lutionary activity against the Ottoman govemment when the CLJP took power in l9l3 through a coup. The SDHP, in collusion with other Ottoman groups, attempted to assassinate CUP leaders. The assassins were betrayed, and though the more cautious Ottoman branch of the pafty was against illegal revolutionary activity, the plot served as a pretext for the govemment to arrest local members as well. Twenty SDHP members were hanged on June 15, 1915, and their deaths are commemorated even today by the party and other Armenians. Party members participated during the genocide in whatever attempts at defense were possible throughout the Ottoman Empire. The SDHP was also active in Cilicia during the brief return there of Armenians after World War I, and in the battles during which Turkish Nationalists expelled or killed the Armenians.

Operations ln lran, Gaucarur

Meanwhile, in the 1890s the SDHP in kanian territory at first limited themselves to sending aid and expeditions into Ottoman Armenia. Later it actively supported liberal and leftist hanians in the constitutional revolution of l9OG191l with men and arms to provide a better staging area for the liberation of other Armenians, as well as to improve conditions for th Iranian people as a whole. The SDHP facilitated the entry of Georgian, Iranian, and Russian social democrats into Iran.

In the Caucasus, despite ideological similarities the party's focus on liberating Ottoman Armenia was the main obstacle to the SDHP dissolving itself in the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party. Here even more than in the Ottoman Empire, strikes and the organization of industrial workers were undertaken. The Hunchakians dso fought the Russian government's assimilatory policies, going so far as to attempt to assassinate the Russian viceroy in Tiflis in 1903. They participated in the Armeno-Tatar battles of 1905.

The party supported in principle the so. vietization of Armenia, with many of its own members leaving the party to become Soviet leaders. It resolved n 1924 to support Soviet Armenia and the spread of Marxism throughout the world, wherever Armenians lived, through legal means, while pursuing the liberation of Turkish Armenia.

As a diasporan party the SDHP had to resist on the one hand Soviet pressures for dissolution into the Comintern, and attacks within the diasporan branches of the Committee for Assistance to Armenia and other bodies established by Soviet Armenia. After the sovietization of much of Eastern Europe, the SDHP's activities were curtailed there, too. One group of members left the party in the 1930s over its unwillingness to openly break with the Soviet Union as an oppressive state.

Glrght ln the Gold

On the other hand, as a result of the world-wide Cold War, the party lost a great deal of membership due to political harassment from the right in the United States, [cbanon and elsewhere. The Armenian Revolutionary Federation, its major political opponent in the Diaspora, sided with the anti-Soviet powen. Thus, continued struggles in [.ebanon, including the deaths of several hundred Armenians who fought each other along political lines in the 1958 lrbanese Civil War, ended up with the ARF in a dominant position with govemment and U.S. sup. port. The SDHP did find an ally in the capitalist Armenian Democratic Liberals, who sup,ported Soviet Armenia for pragmatic reasons. The world-wide rivalry intensified after the ARF in 1956 gained control in a political sense over the Catholicosate of Sis (Antelias).

The gravity of the 50ttr anniversary of an Armenian Genocide largely unrecognized by the world in 1965 led to cooperation between the political parties during commemorations. This continued on a larger scale during the 6(hh anniversary commemorations in 1975. The l-cbanese Civil War, which began the same year, encouraged cooperation irmong the three main Armenian political parties for the self-defense of the lrbanese Armenian community. It also led to emigration to the United States and Canada, among other places, allowing for the reconstitution of active SDHP branches. The halt of the Cold War and the changes in the Soviet Union adminstrated by Mikhail Gorbachev eliminated some of the rea- sons for hostility among the parties, too. All SDHP branches in the U.S.S.R. were dissolved.

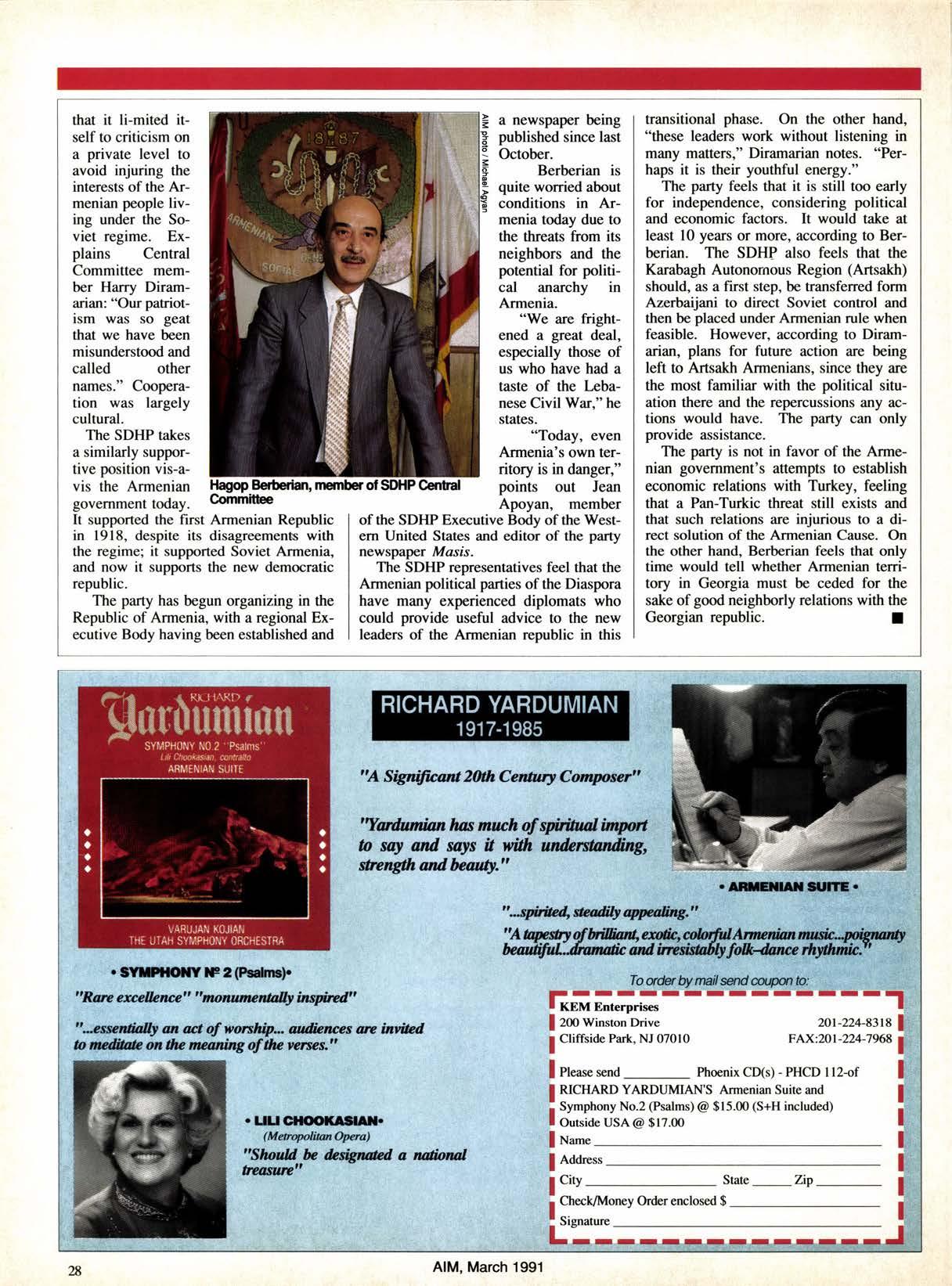

Despite these changes, SDHP Central Committee member Hagop Berberian recently stated that SDHP ideology remains unchanged as a combination of socialism and democracy. Many of the changes that have taken place in the Soviet Union are attempts to introduce democracy to socialism, believes Hagopian. Though the implementation of socialism in the USSR may have not succeeded in the past, that does not invalidate the ideology iself.

Today, the party openly condemns Stalin as an exploitative ruler and declares that it li-mited itself to criticism on a private level to avoid injuring the interests of the Armenian people living under the Soviet regime. Explains Central Committee member Harry Diramarian: "Our patriotism was so geat that we have been misunderstood and called other names." Cooperation was largely cultural.

The SDHP takes a similarly supportive position vis-avis the Armenian govemment today.

It supported the first Armenian Republic in 1918, despite its disagreements with the regime; it supported Soviet Armenia, and now it supports the new democratic republic.

The party has begun organizing in the Republic of Armenia, with a regional Executive Body having been established and a newspaper being published since last October.

Berberian is quite worried about conditions in Armenia today due to the threats from its neighbors and the potential for politi- cal anarchy in Armenia.

"We are frightened a great deal, especially those of us who have had a taste of the l-ebanese Civil War," he states.

"Today, even Armenia's own territory is in danger," points out Jean Apoyan, member of the SDHP Executive Body of the Westem United States and editor of the party newspaper Masis.

The SDHP representatives feel that the Armenian political parties of the Diaspora have many experienced diplomats who could provide useful advice to the new leaders of the Armenian republic in this transitional phase. On the other hand, "these leaders work without listening in many matters," Diramarian notes. "Perhaps it is their youthful energy."

The party feels that it is still too early for independence, considering political and economic factors. It would take at least l0 yezrs or more, according to Berberian. The SDHP also feels that the Karabagh Autonornous Region (Artsakh) should, as a frst step, be transferred form Azerbaijani to direct Soviet control and then be placed under Armenian rule when feasible. However, according to Diramarian, plans for future action are being left to Artsakh Armenians, since they are the most familiar with the political situation there and the repercussions any actions would have. The party can only provide assistance.

The party is not in favor of the Armenian govemment's attempts to establish economic relations with Turkey, feeling that a Pan-Turkic threat still exists and that such relations are injurious to a direct solution of the Armenian Cause. On the other hand, Berberian feels that only time would tell whether Armenian territory in Georgia must be ceded for the sake of good neighborly relations with the Georgian republic. I