8 minute read

il0llt0il1 il

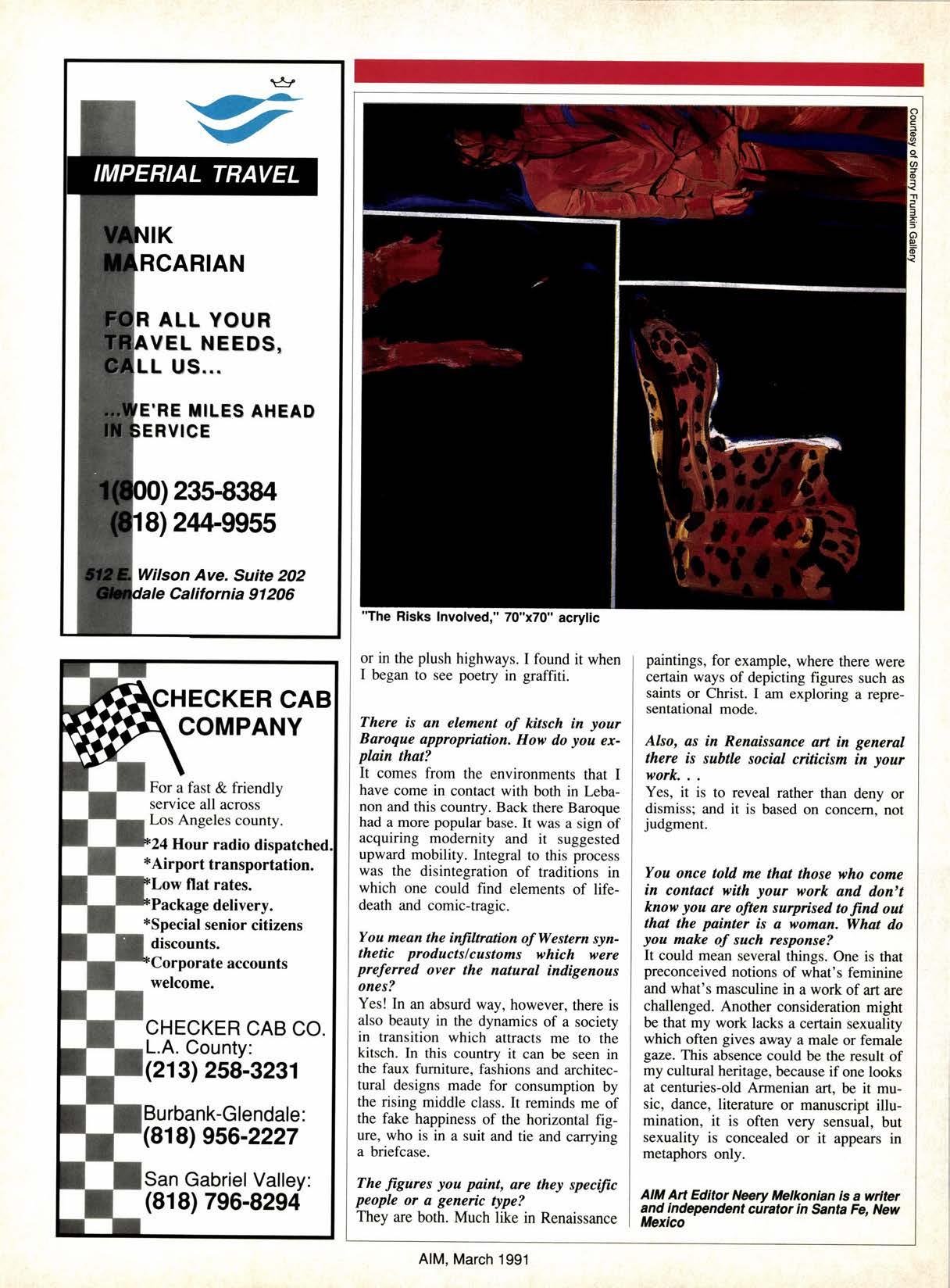

As events in the Miiltle East continue to nake hedlines, an artist who comes tron that part of the global village would have plenty to oller us through her work* a.-Frcp*.tive on rssugg relatd to expriencing war, conlronting the prplexities ol lile in a diaspn, and being a womah in maledoninatd socidies. ' llanoukian's most recent works are on display with those ol llissak Tenian at the S_heny Frunkin Gallery in Santa Monica, Cafitomia. The exhibit, entiild,Two lrom Beirut," runs llarch &April 6.

.^_Bom_in *iryt, .Lefulngn, *ta Manoukian's pintings have been exhibited since 1.976 in.tlp tliddle.East, Annania, Ew^ope and nbw in tfre unlted states. cunentty an instructor of art in La cresent4, cdlitornia, where she resides, llanoukian'has grduated lron the Adeny of Fine Arts in Rome and has studid at Barkins cotlqe of rxhnology in Londdn. she is the author of two books on the art of Lertnese children during the civil war.

Advertisement

By NEERY ilELKONIAil

NM: lYhot does the "7" shape or the horizontal-vertical element of your compositions in essence represent?

MANOaKIAN: The fusion of primordial signs and everyday realities. One symbolizes the spiritua[metaphysical, and the other socio-political dimensions.

Are they, then, the meeting of two opposile notions as well?

Yes, as in life-death, masculine-feminine, intellectual-sensual, etc.

In realiflt, aren't fusions of opposites such as the spiritual and the socio-political contradictory?

Not at all. Wherever one is spiritually that's where one is as a socio-political being. When ego or individuality is stressed, however, one becomes destructive because there is no unity or harmony. That is when one may be alive but dead at the same time.

So which is which in your compositions?

The horizontal is the ego. It can also signify other problems such as: violence, political turmoil, neglect or abuse of nature. It is when decadence prevails. .

What is the significance of objects likt the chaits, columns and minors which you incorporate in some of the paintings?

They are baroque in design, which is derived from organicfliving forms, but their appropriation expresses decay or death of the natural.

war is a rlpened version of conlllcts registered in my work"

Your most recent work introduces the circle; what specific meaning do yoa afroch to thol universal symbol?

For me the circle represents our "center," meaning to be in harmony with one's self. Its juxtaposition with the horizontal male figure symbolizes a loss of that center.

Why the ahsence of the feminine figure in your compositions?

I left her out primarily to avoid narration or anecdotal interpretations. to stay with the bare essence of what I am orying to resolve, which goes beyond problems related to gender conflicts.

How or when did these explorations entcr your work ?

In the late '60s and early '70s, after my retum from Italy in 1967 and before the eruption of the Lebanese civil war in 1974, I was preoccupied in dealing with the big philosophical questions concerning life-who are we, where do we come from, and where are we heading? Those kinds ofquestions. It was a period ofselfindulgence. This decadent existence was also present throughout the country. There was an overall atmosphere of stagnation. Despite constant attempts to resist that life, a great boredom overcame me and I began to paint obsessively large canvases that depicted white wrinkled sheets in big empty spaces. To answer your question, those compositions were horizontal, and in retrospect they represented an enormous burden that I was carrying.

Which was what, and how did you cope with it?

It was the predominance of personal explorations which later, during and after the war, came to include others. But before that occurred I went through a major depression, which I overcame only when I began to integrate metaphysical contemplations to explain the world. To this day I remember the experience of a huge light that I saw for two days. It was through a spiritual process that I healed myself and got out of the isolation of the previous four years. I began to love people in ways I wasn't capable of before. It enabled me to redefine my relation to the socio-political environment, which later helped me endure the war. Anyway, that is also when I began to incorporate people and bright colors in my paintings.

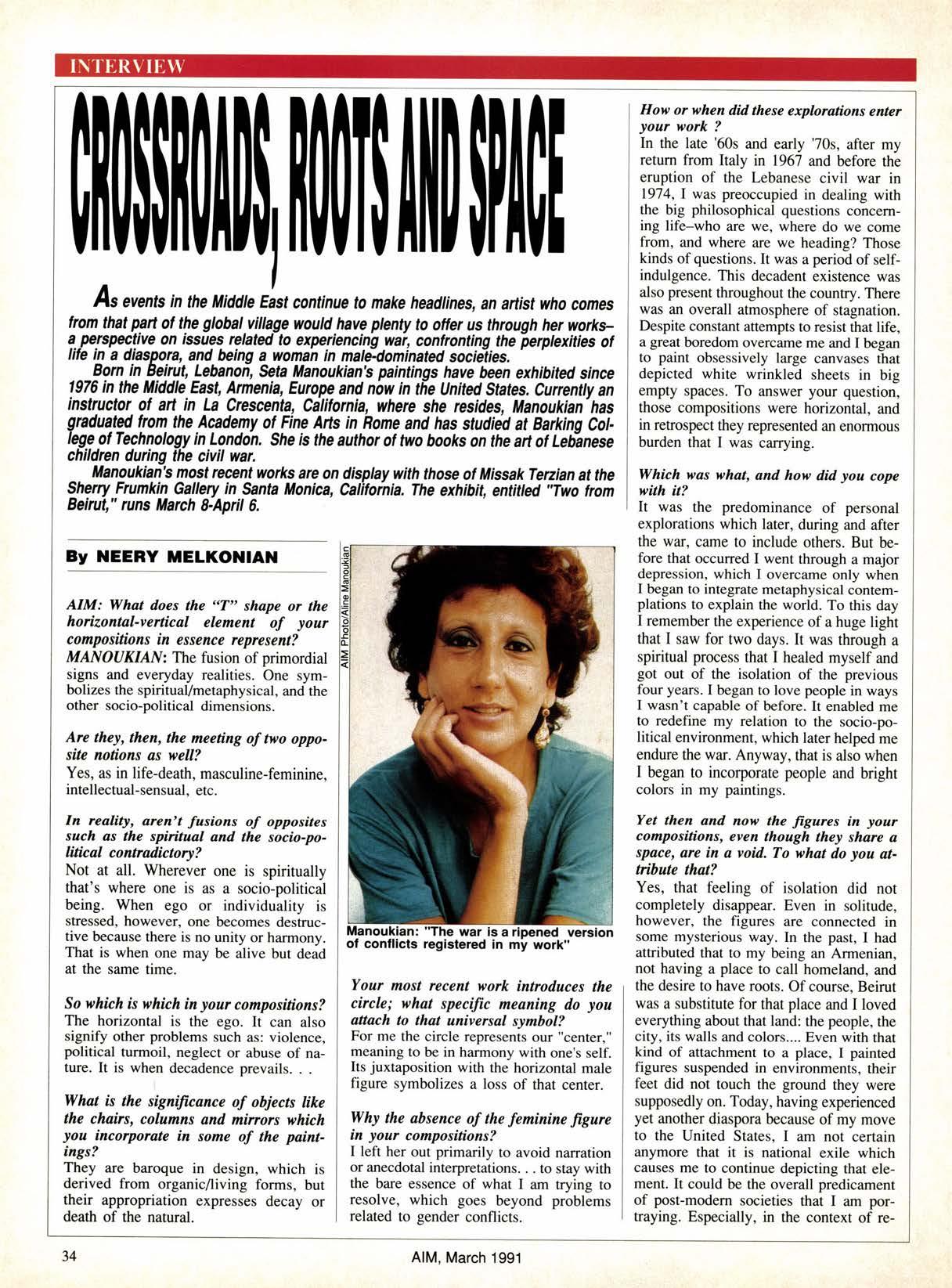

Yet then and now the figures in your composilions, even though they share a space, are in a void. To whal do you attribute thal?

Yes, that feeling of isolation did not completely disappear. Even in solitude, however, the figures are connected in some mysterious way. In the past, I had attributed that to my being an Armenian, not having a place to call homeland, and the desire to have roots. Of course, Beirut was a substitute for that place and I loved everything about that land: the people, the city, its walls and colors.... Even with that kind of attachment to a place, I painted figures suspended in environments, their feet did not touch the ground they were supposedly on. Today, having experienced yet another diaspora because of my move to the United States, I am not certain anymore that it is national exile which causes me to continue depicting that element. It could be the overall predicament of post-modern societies that I am portraying. Especially, in the context of re- cent developments in global affairs, I am questioning whether anyone has roots; how we ever had roots; what does having roots mean

Italy in the '60s was an excifing place both artistically and politically. What kind of eflects tlid it have on you and how did it feel to return to Lebanon af' terward?

Overall the retum to a Third World environment took some adjustment, especially for a woman artist in a male dominant society. Yes, in comparison, art was everywhere in Italy and was integral to the political climate. In fact, I entered politics through the realm of Italian cinema with Pasolini, Fellini, etc. So I experienced a major void. In painting, for example (other than children's art, which for me were more genuine depictions of everyday realities), artists were still working in the tradition of arabesque, impressionist and abstract genres. The constraints I encountered, in both my socio-political and my artistic environments, led me to leave for the U.S. in 1986.

Whal was the nature of your involve' ment wilh chiWren and their art?

Besides teaching at the university I gave art lessons to children and have produced two books on their work. One of them, in 1976, embodied the works of children from a poor Muslim community located between the east and west zones. I used to visit them three times a week, gathering the children from the streets and conducting art lessons in an abandoned school. The proceeds from the sale of the books went to buy food and other goods for the community. The book published in 1982 brought together works by children from mixed ethnic and economic backgrounds.

Do you consider the extent of your in' volvement in the war, vis-a-vis the chil' dren, an existential or political one?

I cannot separate the two. I wasn't allowed to fight and I couldn't remain inactive, protected by the four walls of my studio. I did similar visits to mental institutions and hospitals. It is true that the war provided me with yet another aspect of painting, but it was to personalize and understand experiences of others. That is why I do not comprehend how an artist like Robert Longo can take a photographic image of Beirut and pretend to have captured the devastation by depicting corpses and rubble. I find that to be a very superficial relation. Those of us who experienced the war could not approach art from that simplistic angle. The physical destruction of Lebanon was one manifestation of the larger, more complex, destruction.

At one point you implicd thal the war was inevitable. As iI it liheraled you and the country, in general, from the experi' ence of boredom, void and decodence which you perceive as another torm ot death . Yes, but it should not mean that the country did not worsen due to the war.

The war is a ripened version of conflicts registered in my work.

How did your move to the United Sutes affect your work ?

Gradually, the figures whose feet were not on solid ground began to acquire the horizontal-vertical "T" shape. My distancing from the war helped develop this clearer imagery. That is probably due to daily life being relatively simpler in this country, which is allowing me to concentrate on fewer issues and take them further.

What did it take tor you to adiust to this land and culture?

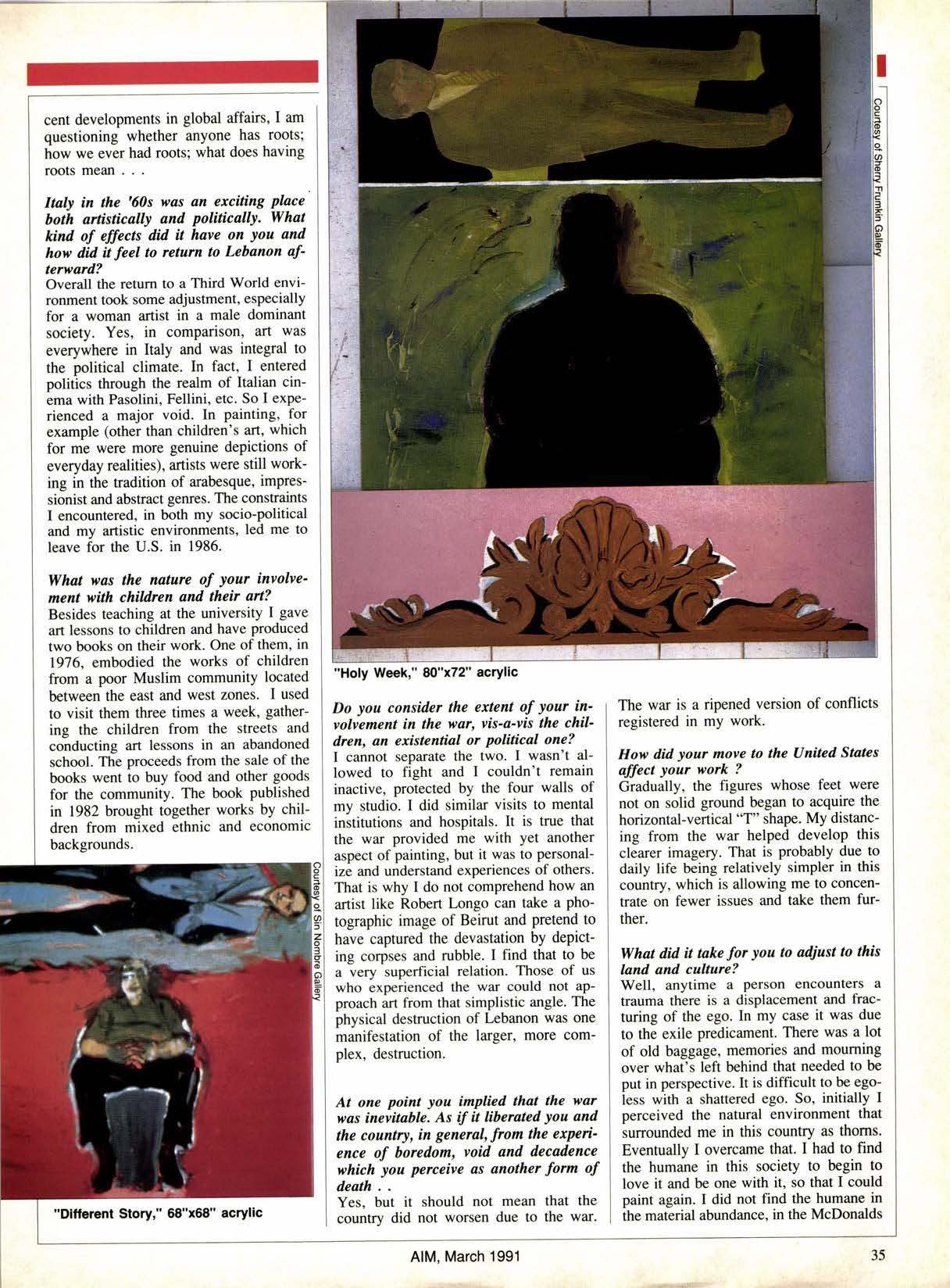

Well, anytime a Person encounters a trauma there is a displacement and fracturing of the ego. In my case it was due to the exile predicament. There was a lot of old baggage, memories and mouming over what's left behind that needed to be put in perspective. It is difficult to be egoless with a shattered ego. So, initially I perceived the natural environment that sunounded me in this country as thoms. Eventually I overcame that. I had to find the humane in this society to begin to love it and be one with it, so that I could paint again. I did not find the humane in ahe material abundance. in the McDonalds

'The RIsks lnvolved," 70"x70" acrylic or in the plush highways. I found it when I began to see poetry in graffiti.

There is an element of kitsch in your Baroque appropriation. How do loa explain that?

It comes from the environments that I have come in contact with both in Lebanon and this country. Back there Baroque had a more popular base. It was a sign of acquiring modernity and it suggested upward mobility. Integral to this process was the disintegration of traditions in which one could find elements of lifedeath and comic-tragic.

You mean the infiltrotion of Western syn- thetic productslcustonts which were prefened over the nataral indigenous ones?

Yes! In an absurd way, however, there is also beauty in the dynamics of a society in transition which attracts me to the kitsch. In this country it can be seen in the faux fumiture, fashions and architectural designs made for consumption by the rising middle class. It reminds me of the fake happiness of the horizontal figure, who is in a suit and tie and carrying a briefcase.

The tigures you paint, are they specific people or a generic type?

They are both. Much like in Renaissance paintings, for example, where there were certain ways of depicting figures such as saints or Christ. I am exploring a representational mode.

Also, as in Renaissance art in general there is sabtlc social criticism in your work.

Yes, it is to reveal rather than deny or dismiss; and it is based on concern, not judgment.

You once told me that those who come in contact wilh your work and don't know you are often surpriscd n find out that the painter h a woman. What do you make of sach response?

It could mean several things. One is that preconceived notions of what's feminine and what's masculine in a work of art are challenged. Another consideration might be that my work lacks a certain sexuality which often gives away a male or female gaze. This absence could be the result of my cultural heritage, because if one looks at centuries-old Armenian art, be it music, dance, literature or manuscript illumination, it is often very sensual, but sexuality is concealed or it appears in metaphors only.