3 minute read

EmilyFinley&LillyanPriest,Students,

DepartmentofLandscapeArchitecture, FayJonesSchoolofArchitecture+Design, UniversityofArkansas

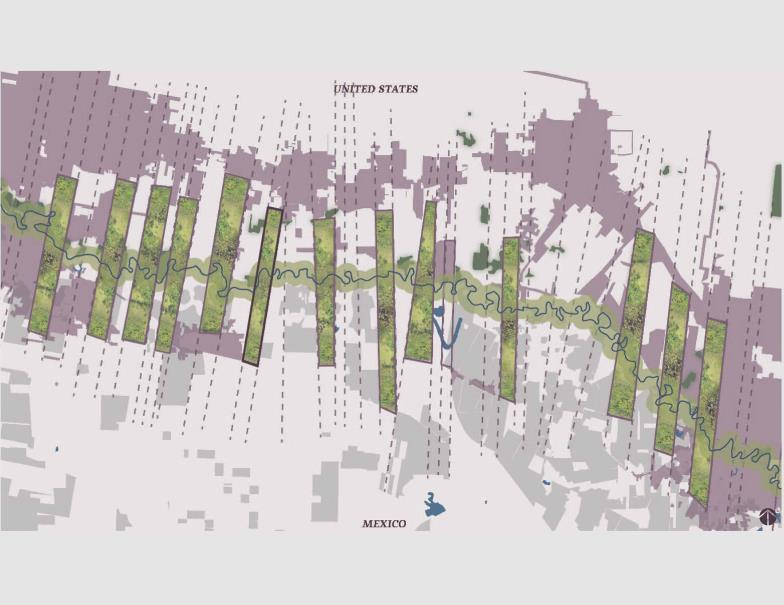

The Lower Rio Grande/Río Bravo Valley is one of the fastest-growing regions in the United States, with a population of 10.4 million people, expected to increase by 175% before 2050. It is also one of the most important ecological zones in the world where more than one billion migratory birds pass through the region each fall, drawing thousands of recreational birdwatchers from across the globe. However, the Valley also faces struggles of social disconnection and ecological fragmentation. To address these challenges, we first studied the region’s history-a fascinating tale of booms and busts, war and peace, poverty and prosperity, belonging and isolation. From that history emerged a physical framework for reconnection, based on historic patterns, which we have named the ‘sutura’ network. We propose the sutura network, with its trails providing physical connection, rows of palms providing visual identity, and social nodes and ecological projects providing opportunities for equitable community access, will heal and reconnect the Lower Rio Grande/Río Bravo Valley region for a healthier and more sustainable future.

Advertisement

In a 1951 Landscape essay, writer and scholar J.B. Jackson makes a compelling claim: “Rivers are meant to bring people together, not keep them apart.” His claim is evidenced throughout history, across time and place, as the magnetic pull of water on human settlement, culture, and development are seen time and time again. The Lower Rio Grande/Río Bravo Valley is no exception. The banks of the Rio Grande have been home to indigenous peoples, Spanish conquistadors, Tejano natives, farmers, ranchers, soldiers, entrepreneurs, travelers, artists, and modern-day inhabitants who spend their lives investing in the place they live–all drawn to the waters of the Rio Grande at the very heart of the Valley. In addition to permanent residents, the population of the Valley increases by over 100,000each winter as thousands of “winter Texans” migrate to the Valley to enjoy warm winter weather, access to inexpensive dental and medical goods and services across the border in Mexico, and seasonal ecotourism activities such as birdwatching and wildlife viewing.

Despite its sustained population growth, the valley faces many long-term challenges. Its ecological systems have disintegrated over a century of subdividing and clearcutting most of the land to prepare it, almost exclusively, for agricultural use. Its social communities and sister cities that developed parallel to one another have been segregated across an international border, which happens to be represented by the river. Tall, threatening walls and security structures loom over the landscape on the United States side a few miles in. The region’s heavy economic dependence on agriculture and the water provided by thriver has added significantly to these issues.

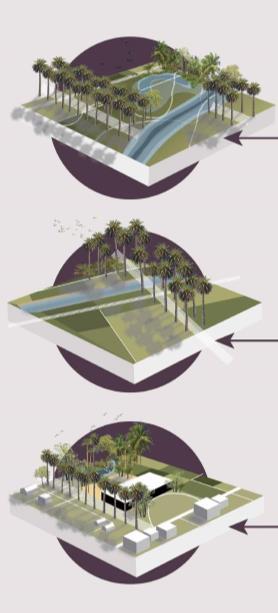

This project aims to heal that regional divide by restoring and reconnecting access to the river through historic landscape geometries. ‘Porción’-Spanish for portion-lines form the foundation of many political boundaries throughout the region and so are still visible in town development and lot lines. Palm tree rows represent visual iconography of the Valley as well as were important in delineating agricultural fields apart from each other, the portion lines. In his paintings, locally well-known artist Gabriel Salazar represents palm tree rows, agricultural fields, rivers, resacas, brushlands, and many other landscape features which bring to light the history and culture of the Rio Grande/Río Bravo Valley. We borrow and intervene his paintings to communicate our concept. Restoring these rows with intention, including multiple species of native palm trees, which lead to the river provides an unconscious path for the people of the region to remember its roots at the river, moving toward it visually and physically. Trees are also important for shade in the hot, humid, tropical/temperate local climate so that people of all ages can safely walk, bike, or ride to the river. The river has served as the physical and cultural heart of the Valley since its very founding and must continue to do so. Therefore, the river remains at the heart of the sutura network, connecting each side to the other. Today, the river is highly patrolled, controlled, and over-allocated with few congested bridges connecting its banks; however, it can serve as a connector for its people again. The historical geometries of this place highlight the nature of the river and what its connection to it means.

Networks of social nodes, trails connection, and renaturalization can instill an old vision of the valley as new again. As regeneration happens locally in the cities and spreads through the region, the sutures begin to create larger healing for the region. From McAllen and Reynosa to Brownsville and Matamoros, socially and environmentally these places will once again be connected to the river as it exists in this larger system.

SUTURES OF THE RIO GRANDE / BRAVO: RESTORING ACCESS

THROUGH HISTORY & ECOLOGY, Brownsville, Texas & Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico