Gods & Rats Rejoice?

Hammer Time Testbeds Architecture & Disability

“In the United States, people with disabilities in the architecture profession and architectural academia are statistically invisible,” disabled designer and New School professor of architecture David Gissen wrote in AN in 2018. “Neither the American Institute of Architects nor the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture collect data on the number of architects or architecture students in the United States who self-identify with physical or cognitive disabilities,” he wrote. While in the past few years the discipline itself has made strides in becoming more inclusive, Gissen argued then that “it is time that we let people with disabilities partake in this important transformation occurring in American architectural education and the profession.”

Five years later, Gissen’s new book, The Architecture of Disability: Buildings, Cities, and Landscapes beyond Access, marks a watershed moment in this ongoing struggle for disability equity. continued on page 81

Distinctive designs. Unparalleled solutions.

At BŌK Modern, we think beyond the ordinary. As a single-source provider of a complete line of structurally integrated architectural metal systems for the building envelope, we ensure your designs are realized. We speak your language and are committed to design excellence from concept to completion.

2023 AIA Conference, San Francisco is held at MOSCONE CONVENTION CENTER

Around the World

Cofounder and CEO

Diana Darling

Executive Editor

Jack Murphy

Art Director

Ian Searcy

Web Editor

Kristine Klein

Market Editor

Sophie Aliece Hollis

Associate Newsletter Editor

Paige Davidson

Assistant Editor

Chris Walton

Vice President of Brand Partnerships (Southwest, West, Europe)

Dionne Darling

At the outset of her recent Aga Khan Program Lecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Tosin Oshinowo defined the term àse as “the power that makes things happen and produces change.” The word, also the title of the architect’s presentation, comes from the Yoruba religion. (Oshinowo, from Nigeria, is Yoruba.) She related this force to the intention or contextuality of material in architecture and shared how the close study of environmental context is important in her work.

Oshinowo told the story of designing new structures for a village in northeast Nigeria whose residents had been displaced in 2015 after being attacked by Boko Haram.

(AN covered the project last summer.) Educated as an architect in London, Oshinowo worked there for SOM and in Rotterdam for OMA before returning to Lagos and eventually founding her practice, cmDesign Atelier, in 2012. For this project, she had to apply her skills to a new cultural context, as she had never been to northeastern Nigeria. The architect set to work understanding the familial structures, weaving practices, and traditional compound-house layouts of the Kanuri people. That research, joined with an attention to cost and the speed of construction, shaped the complex’s architecture.

The effort captures two ideas that are central to contemporary architectural practice: a close attention to local environments and users, and the deployment of design in response to crises. These ideas are valid everywhere; see, as one example, this issue’s Studio Visit with Duvall Decker on page 16.

Days later, Oshinowo was the leadoff presenter at The World Around (as seen in the image above), a one-day symposium in New York on Earth Day. Those two aforementioned ideas were on full display during the afternoon’s presentations, organized by curator Beatrice Galilee, about “architecture’s now, near, and next,” which had a consistent focus on the climate crisis. Additionally, winners of the group’s Young Climate Prize Awards were recognized. There were friendly New York faces, including Andrés Jaque (whose Reggio School won AN’s Project of the Year last year and was reviewed in AN’s previous issue), Dominic Leong (whose firm, Leong Leong, was named one of AN Interior’s Top 50 Architects and Designers in 2022), and Vishaan Chakrabarti (whose office, PAU, remains a part of shaping the fate of Penn Station; see page 12).

Other international speakers were less familiar to me: Ana Maria Gutiérrez presented a new bamboo building realized at Organizmo, a center for regenerative training and the exchange of intercultural knowledge in Colombia; Deema Assaf, of TAYYŪN, is attempting to rewild Amman, Jordan, through

the planting of new forests; Fernando Laposse, a designer based in Mexico City, is researching avocados, a conflict commodity as their production in the Mexican state of Michoacán is largely controlled by drug cartels; and Joseph Zeal-Henry, from London, shared Sound Advice, a platform for exploring spatial inequality, ahead of its curation of the British Pavilion at the fast-approaching Venice Architecture Biennale.

I was inspired by the day’s sessions. They made me think about the venue’s entanglement with larger issues. We were gathered on the Upper East Side in the basement auditorium of the Guggenheim Museum, an institution that has faced criticism for its handling of race and, earlier, the working conditions at the construction site of a new outpost in Abu Dhabi. Inspired by the day’s lessons and fatigued by their pace, my mind drifted upward into the museum’s rotunda. With ecology on the brain, I thought of how Frank Lloyd Wright’s spiraled void summoned less the image of the Tower of Babel or a “concrete funnel”—as Lewis Mumford wrote in 1959—and more that of an open-pit mine, the kind of excavation from which the Guggenheim family extracted their fortune in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Ecological concern also powers this issue’s feature section (page 21) and in part the Focus section about facades (page 29).

Facade design matters because it largely establishes a building’s thermal performance and is often layered in specialized assemblies sourced from around the world. Continued innovation within this part of the construction industry will aid efforts to reduce architecture’s carbon emissions.

Planetary relations are top of mind as I prepare for this month’s Venice Architecture Biennale, curated by Lesley Lokko with the theme of Africa as a laboratory of the future. AN will, of course, provide thorough coverage of the main exhibition and assorted national pavilions. (As a teaser, see my interview with the curators of the American pavilion on page 82). AN will also host an event on May 18 at Carlo Scarpa’s Fondazione Querini Stampalia to celebrate the life of William Menking and mark the importance of architectural criticism through a symposium with five critics: Erandi de Silva, Mohamed Elshahed, Davide Tomaso Ferrando, Inga Saffron, and Oliver Wainwright. Please join us if you will be in Venice this year.

One voice almost missing from the action is that of Aaron Seward, who departed his role as AN’s editor in chief last month. We at AN wish him continued success. But AN readers aren’t fully bereft of Seward’s wisdom: Turn to page 26 to read his swan song. Jack Murphy

Director Brand Partnerships (East, MidAtlantic, Southeast, Asia)

Tara Newton

Sales Manager

Heather Peters

Assistant Sales Coordinator

Izzy Rosado

Vice President of Events Marketing and Programming

Marty Wood

Program Assistant

Trevor Schillaci

Audience Development Manager

Samuel Granato

Events Marketing Manager

Charlotte Barnard

Business Office Manager

Katherine Ross

Design Manager

Dennis Rose

Graphic Designer Carissa Tsien

Associate Marketing Manager

Sultan Mashriqi

Marketing Associate

Anna Hogan

Media Marketing Assistant

Wayne Chen

General Information: info@archpaper.com

Editorial: editors@archpaper.com

Advertising: ddarling@archpaper.com

Subscription: subscribe@archpaper.com

Vol. 21, Issue 3 | May 2023

The Architect’s Newspaper (ISSN 1552-8081) is published 7 times per year by The Architect’s Newspaper, LLC, 25 Park Place, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10007.

Presort-standard postage paid in New York, NY. Postmaster, send address changes to: 25 Park Place, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10007.

For subscriber service: Call 212-966-0630 or fax 212-966-0633.

$3.95/copy, $49/year; institutional $189/year. Entire contents copyright 2023 by The Architect’s Newspaper, LLC. All rights reserved.

Please notify us if you are receiving duplicate copies.

The views of our reviewers and columnists do not necessarily reflect those of the staff or advisers of The Architect’s Newspaper.

Corrections

An article about the St. Sarkis Armenian Orthodox Church misstated the provenance of the commission for David Hotson Architect. Rather than being won via competition, the office came to the project via Stepan Terzyan, an Armenian architect who had worked for him on projects in New York and Armenia. (Pre-2008, Hotson’s practice had a location in Yerevan, Armenia’s capital.) Terzyan’s family, with sponsorship from Hotson, immigrated from Armenia to Texas, where they joined a local Armenian church that was worshipping in a converted residence. Seeking a permanent home, the congregation began work on a new-construction complex. Terzyan worked with the effort’s lead donor and philanthropist Elie Akilian on early stages before subsequently inviting Hotson to head the design team. Additionally, the gaps between the panels are 1 centimeter wide, not 1 inch wide. Corrected article texts are available on AN ’s website and in the digital version of the March/April issue.

Due to an editorial oversight, a review included an incorrect abbreviation of its subject’s title. The publication, edited by Samia Henni, is named Deserts Are Not Empty Corrected article texts are available on AN ’s website and in the digital version of the March/April issue.

6 Open News

Black Sands California’s Central Park

FÖDA and Gensler create a materially rich interior for chef Aaron Bludorn’s latest venture.

SWA Group shares a comprehensive master plan for Irvine’s unfinished Great Park.

Seventeen years after Ken Smith Workshop’s master plan for Irvine, California’s Great Park was approved, an updated scheme will envision a new era for the park.

SWA Group’s Laguna Beach studio has released its plans for the 1,200-acre Orange County park, working with local planning and urban design firm Kellenberg Studio.

Currently, the park features a visitors center, an outdoor agricultural classroom, a water park, extensive athletic facilities, an arts complex, considerable parking space, and 1.5 miles of pedestrian and cycling trails, which will soon be joined by an amphitheater, a museum complex, a botanical garden, and a public library.

Built on the site of the former Marine Corps El Toro Air Station, the park has been long envisioned as California’s Central Park. A 2006 design competition, won by Ken Smith Workshop, brought forth a new vision for the park. While some parts of the park came to fruition, including an often-photographed orange hot air balloon ride, the full plan was never realized.

The park has become a fixture in local politics. In a deposition, a worker from the construction management company MCK, which performed program and construction management and filled advisory roles on the project, described aspects of Smith’s design as impractical. This included a manmade lake that would have required the Navy to clean up contaminated groundwater and the redirection of water into a wildlife corridor. The Smith plan also included an artificial canyon.

Navy Blue

2445 Times Boulevard

Houston

713-347-7727

navybluerestaurant.com

Over time, Rice Village, an eclectic, tree-lined Houston shopping center that originated in the late 1930s and ’40s, has grown into a beloved (and periodically down-at-the-heels) destination for nearby residents, hobbyists, college students, home-goods shoppers, moviegoers, and diner patrons. Beginning in 2018, public space upgrades like covered outdoor seating, landscaping, and widened sidewalks have attracted new upscale shops and restaurants to open amid decades-old favorite haunts, bringing a renewed vibrancy to the district.

Navy Blue, a new seafood restaurant concept helmed by Aaron Bludorn, a veteran of New York’s Café Boulud and operator of his eponymous restaurant in Houston, opened late last year. The eatery represents the latest entry in the Village’s refashioning into a fancy Houston destination. Designed by Austin-based brand consultancy and design studio FÖDA in close collaboration with Gensler, the restaurant has transformed a former food hall into an expressive dining room. (FÖDA also worked with chef Bludorn on the design of his prior venture, his first in Houston.)

Upon entering, diners are greeted by an oyster shell–inspired reception area perforated with circular apertures, in accidental homage to Jean Prouvé. Curved bays of deep blue Japanese tile and tall white oak planks differentiate upholstered banquettes and tables in the dining room, which is served by a show

kitchen, from the seating areas around the bar; both are surfaced in white Japanese tile.

The design leaves the concrete structure exposed. Above, the ducting and concrete are offset by jellyfish-like wire lamps. Glimmering tiles on the exterior facade and glowing chartreuse tiles in the bathroom areas strategically animate the walls. Throughout, subtle elements (like hidden mirrors to accentuate handblown glass pendant lights in the booths) and discreet space planning (to ease natural circulation in the dining room and offer the servers view corridors while concealing them from guests) afford a refined dining experience.

“The working title for this project was Black Sands,” Jett Butler, founder and chief creative officer of FÖDA, told AN . (Prior to starting the office in 2003, he studied architecture.) “We used this prompt to avoid nautical kitsch; instead, we centered on that moment where the raw, visceral nature of the sea collides with the land.”

Butler continued: “The booths curl into one another in waves of tile, the frames of the oak center planes curve inward into themselves, breeze-blocks emerge as a cylinder with circular perforations that cast layered ellipses on the floor, the flowing script of the menus is hand drawn and spaced with nautilus shell ratios.... The room is simple, the gestures are spare. Yet Navy Blue is loaded with subtle symbolism.”

The concept—and the cuisine, of course— has already won over critics: Writing in Texas Monthly in March, Patricia Sharpe proclaimed that “Navy Blue is the best restaurant to open in Texas in the past year.”

After Governor Jerry Brown shut down California’s municipal development agencies in 2011, the city lost a potential funding source for the park. The city then negotiated with a development company, FivePoint, to construct high-end single-family housing around the park. FivePoint had already

been working with the city on the park’s development, and after the state-level changes were passed, Irvine allowed FivePoint to triple the number of houses being built in the area surrounding the park. The housing scheme was key to the plan not only in terms of the city relinquishing a degree of control over the larger project to a private developer but also in that homeowners in the neighborhood adjacent to the park pay additional taxes for infrastructure development through a Mello-Roos scheme.

In July 2022 the Irvine City Council approved a new plan for the park. Funding will continue to come from the Mello-Roos scheme and bonds, with some of the park’s original promises coming back into development.

SWA’s plan breaks the park into five sections: The Heart of the Park will include an amphitheater that could hold 12,000 seats, a farm, and lakes; the Cultural Terrace will convert existing hangars, alongside new construction, into a museum complex; a botanical garden and Veterans Memorial Park will include a public library and “living laboratory” for species native to Southern California; the Bosque will be “a sculpted linear park of naturalized landscape trails, playgrounds, and native California chaparral”; and a 200acre sports park will complete the plan.

SWA’s design for the lake system covers 22 acres. The forest reserve and botanical garden will cover an additional 40 and 60 acres, respectively. A large promenade will connect the park’s five components and will include tram stops and bike storage facilities. This is key, as the Irvine Transportation Center is located across from the southwest side of the park.

SWA managing principal Sean O’Malley described the park as an act of hope: “Planting trees and planning this endeavor is an investment in our future.” Chris Walton

7 News News

Train as Theater

Gensler to renovate Baltimore Penn Station’s historic building and add a new facility.

Venting the Stacks

An archive at Yale University and a new website continue the legacy of architect Kevin Roche.

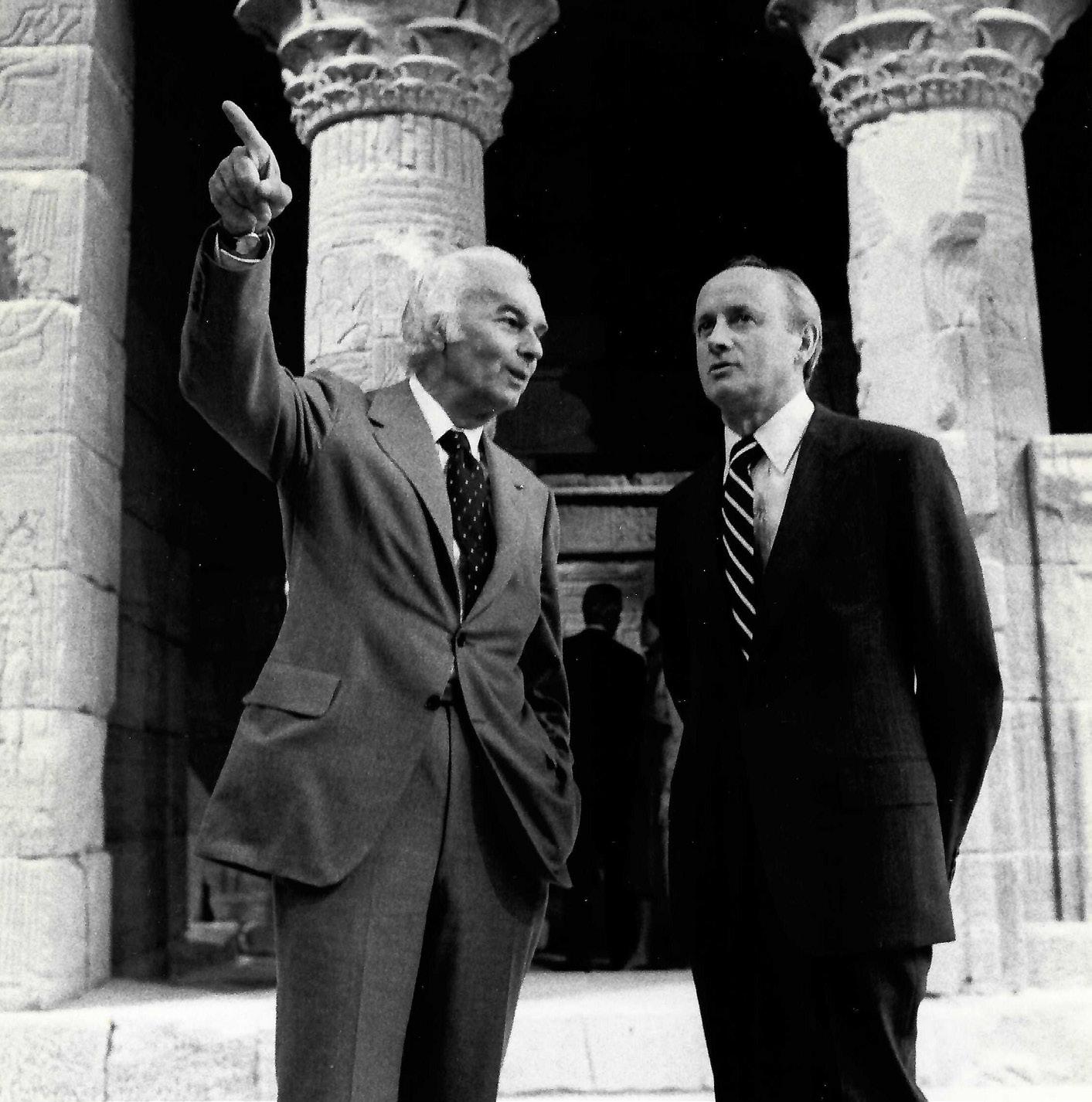

Yale University Library’s Manuscripts and Archives department has acquired an archive of the career of architect Kevin Roche. Roche’s family donated correspondence, project documentation, interviews, drawings, and photographs from the architectural firm of Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo and Associates (KRJDA) to cement the architect’s legacy. In addition to the newly housed archive at Yale, a recently organized legacy website for KRJDA has also launched.

Work on the archival project started in 2007. Robert A. M. Stern, then dean of the Yale School of Architecture, supported the project from the beginning. “The Kevin Roche archive is one of the most important resources for the study and appreciation of postwar architecture,” he noted in a press release. “International in scope and brilliantly occupying the crossroads of corporate postmodernism, it documents the work of a major talent.”

Roche, who was born in Ireland, launched his architectural career in the Michigan office of Eero Saarinen. After Saarinen passed away in 1961, Roche eventually founded a firm with John Dinkeloo in 1966 and completed many of Saarinen’s designs, among them the St. Louis Gateway Arch and the TWA Terminal at JFK Airport. Roche went on to win the Pritzker Prize in 1982. In 2021, following Roche’s death in 2019, the firm rebranded as Roche Modern, and it continues to operate from an office in Connecticut under the direction of Jerry Boryca and Eamon Roche, Kevin’s oldest son.

transferring them. Scinto began working at KRJDA in 1997 as an interior designer and worked as Roche’s executive assistant from 2011 to 2019.

“It was an honor to be chosen by Kevin Roche to be the lead archivist on such a monumental project and I am delighted that people will be able to study the collection today and in the future,” Scinto said in a statement.

Among the items in the collection are drawings and plans for several corporate headquarters designed by KRJDA, including those of the Ford Foundation, Cummins, and ConocoPhillips, as well as a number of museum renovation projects, theaters, and university buildings.

Items in the archive are listed online by project name. They are physically stored at Yale University’s archive locations.

In addition to the archive at Yale, the Roche family has produced an archival website that highlights the history of the firm, the people who shaped it, and information on how the archive was assembled. It also showcases KRJDA’s portfolio with project imagery and building models.

Gensler has redesigned Baltimore’s Penn Station (BPS) to be a multimodal hub open to the public. Set across the train tracks from the existing 1911 edifice, with its Beaux Arts features, the new station which will stage a “train as theater” concept that “sets the design apart experientially, putting the old station and the transit activity itself on display.”

BPS is Amtrak’s eighth-busiest station and the second-busiest in the Maryland Area Rail Commuter (MARC) network. The original station was realized for the Pennsylvania Railroad. It features a granite facade, terra-cotta and cast iron elements, arched windows, and Tiffany glass domes. The station hasn’t been updated since 1984.

As part of the renovation, the existing train hall will be expanded, and the addition will replace a parking lot across the tracks from the main building. The station’s two entrances will be joined by three others.

The expansion will be fronted with an all-glass facade and a low-lying, copper-lined roof that draws inspiration from the existing train hall’s three Tiffany domes. A covered passageway will connect the modern addition to the historic building.

In facing the addition with glass, Gensler has designed a “window to history,” meaning that travelers will be able to view the historic building from the new portion. Similar to the existing station, the expansion will be naturally illuminated by sunlight filtering through the glass elements.

“The expansion maintains clear views to the historic, offering levity and fluidity, where the historic headhouse is designed around ideas of mass and permanence,” Peter Stubb, the project’s design director, told AN

The addition will primarily house ticketing and baggage services for Amtrak, while

the old building’s main concourse will accommodate new retail and restaurant options. In a project that the developers hope to complete by the end of this year, upper floors of the existing Penn Station will house office space, for either a single tenant or as a co-working space.

Renderings of the expansion show a brightly lit, open lobby with tables and seating options where passengers can work or have a cup of coffee while waiting for their train. The glazing overlooks the train tracks below.

The reimagined train station is part of a larger plan to redevelop the neighborhood as a commercial destination. An office complex and adjacent residential development are planned for the area immediately north of the new station. Visuals shared by Gensler and Amtrak depict the office portion as a glass tower that is angular in form and faced with balconies. The surrounding sidewalks and landscape will be improved with new seating and plantings.

“Together, the station expansion and future commercial buildings amplify the presence of Baltimore Penn in the Station North neighborhood—literally bridging the tracks and connecting neighborhoods. By meshing with the city of Baltimore, it stitches it together, strengthening a tapestry that tells the story of a bright future,” Stubb said.

Construction is now underway. Improvements will be made to the existing building this summer, including the installation of a new roof, restoration of old windows, updates to stairs and ramps, and maintenance and updates to the aging mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems. Kristine Klein

The archive includes 789 boxes of Roche’s personal and professional correspondence, along with 954 drawing tubes, 64,000 four-inch-by-five-inch transparencies, and over 88,000 35-millimeter slides.

Archivist Linda Scinto has been responsible for sifting through the materials and objects, cataloging, packaging, and

“Speaking on behalf of my siblings we are delighted to have been able to fulfill our father’s commitment to form this comprehensive archive of KRJDA’s mid to late 20th Century architecture. We are so grateful for Bob Stern’s instigation of the effort in the first place, to Yale for their partnership and of course for the fifteen years of documentation and cataloging put forward by the team at KRJDA,” Eamon Roche shared in a written statement.

The completed archive and the new website follow an announcement last year that the architect’s family would reallocate the money received from Roche’s Pritzker Prize to launch a scholarship program in the name of Roche and his wife, Jane, whom he met while working for Saarinen. KK

Ahoy!

Designs unveiled in “artistic ideas competition” for new National Museum of the United States Navy.

Design teams led by five prominent architecture firms revealed proposals last month for what could lead to the next major museum in Washington, D.C.—a new home for the National Museum of the United States Navy. The selected schemes are by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), Gehry Partners, DLR Group, Perkins&Will, and Quinn Evans.

The five teams were finalists in an “artistic ideas competition” held by the U.S. Navy and its historical and curatorial arm, the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC). The competition was meant to show “the full spectrum of possibilities” for creating a museum and ceremonial courtyard to replace the current 1962 museum, which is on the grounds of the Washington Navy Yard in the District of Columbia.

A location for the new museum has not been finalized, but the Navy has a preferred site at M Street SE and Sixth Street SE, just outside the security fence that surrounds the Navy Yard complex in southeast Washington. For the purposes of the ideas competition, the brief was “site-agnostic,” as one official put it.

The NHHC’s vision is to create a new, “public-facing” museum and campus that will “energize public awareness of the integral role the Navy plays in the defense of our country and in the protection of our interests as a maritime nation.”

Besides honoring service members and veterans, the museum is intended to “engage, inspire and educate civilians, active-duty personnel and future generations of Sailors by connecting cutting-edge interactive and multimedia displays to the Navy’s most important and enduring historic artifacts.”

The goal of the competition, according to planners, was to “share conceptual museum ideas with America” and find out what prospective visitors would like to see included in a new museum.

“The Artistic Ideas Competition is an effort to explore the full realm of artistic concepts that might be incorporated,” a fact sheet distributed at the event stated.

Each finalist received $50,000 for participating. A winner was not named. Organizers said all five submissions will be used to show the possibilities for the prospective museum and the renderings may be used to raise money to build it.

The project’s estimated budget is $475 million, according to the U.S. Naval Institute. Sponsors of the competition say their goal is for the museum to be privately funded. That makes it different from the museums planned by the Smithsonian Institution, which are owned by the federal government and rely on funding from Congress.

Now that the designs have been unveiled, the competition organizers intend to get reaction from the public to see what resonates with potential visitors. The NHHC plans to hold additional public showcases this summer. Charles Swift, the museum’s acting director, said the navy and NHHC hope to arrive at a design and secure funds in time to break ground on October 13, 2025, the Navy’s 250th anniversary.

DLR Group designed a building whose faceted form is meant to be “a dialogue of water and sky,” said principal Dennis Bree. Visitors would enter “through water” and “rise to the sky” via an “interpretive platform lift,” then descend through ramped walkways toward the exhibit galleries, where they’ll learn about the Navy and its history. The building would be clad in reflective metal panels so that its shape would reflect the water and the skies, “forging them together.” The preserved mast of the USS Constitution would be mounted on top of the occupiable portion of the museum, up to 170 feet in the air, making it a city landmark that’s visible from a great distance.

BIG designed its museum as a series of five elongated, gabled galleries that step up in height and represent the five branches of the Navy: Surface, Subsurface, Exploration, Aviation, and Space. The five “wings” merge in a “sinuous plan,” creating a “landmark” atrium space on the inside and a sculptural roofscape on the outside. The designers said the rising of the volumes references “the formation of naval fleets in the ocean and the sky,” while the gables are references to the gabled buildings elsewhere in the Navy Yard. Their copper cladding was inspired by overlapping wood boards or metal plates on a ship’s hull. The wings could be built in two or more phases, as funding permits.

Perkins&Will conceived of the museum as “a physical manifestation of endurance,” symbolic of the “resilient and flexible fiber of the Navy—shaped and strengthened over centuries of maritime power.” Sail-like volumes sweep across the site, expressing a sense of balance between forces “forged by the sea.” The arrival experience marks “the moment a visitor leaves the civilian landscape to join the team-oriented world of the Navy” and explore its history “from the depths to the stars.” The Honor Courtyard is a place where land, air, and sea intersect, and artifacts are displayed in settings that evoke the context in which they function.

Gehry Partners, with Craig Webb as project designer, proposed a large, simple volume with glass on three sides filled with naval artifacts and images that would be visible from outside the building. Inside, images, graphics, and video projections would be layered to tell a story about the different eras in the Navy’s history. Brian O’Laughlin, senior associate from Gehry Partners, said Frank Gehry didn’t propose a highly sculptural form for the museum because he didn’t want the building to overwhelm what the messaging is. The building is “meant to, on a subconscious level, not be so linear and to really convey the depth of who the Navy is.”

Quinn Evans conceived of the building as “Homeport,” a place

meets

community and the Navy

together.” The building’s long, linear forms “reflect the piers, ships and Navy Yard vernacular, providing a connection to the work of the Navy and a greater appreciation for its history and heritage.” With multistory window walls providing views of what’s inside, the design “metaphorically places the individual visitor at the threshold of land and sea, surrounded by immersive experiences and paths of discovery.”

A Second Life

Saved from destruction, a rock installation by artist Elyn Zimmerman is relocated to American University and renamed.

Five massive boulders are arranged in semicircular formation, abutting a reflecting pool on the American University campus in Washington, D.C. This isn’t the first installation of the oversize granite rocks, which have a combined weight of 450,000 pounds. The five pieces compose a work by artist Elyn Zimmerman originally titled Marabar that was commissioned in 1984 as a landscape element for the National Geographic Society (NGS) campus in the nation’s capital.

Marabar was prominently installed in the public plaza at the NGS campus designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) and landscape architect James Urban. Several decades later, a campus overhaul at the NGS called for the removal of the art piece. In 2017 the organization wrote to Zimmerman about its planned campus redesign, detailing in its correspondence the need for the installation to be located elsewhere. The letter gave the artist a deadline and asked her to decide what to do with the sculpture.

“If you do not let us know by then of your intent to move the sculpture, the sculpture will need to be removed by us,” the letter stated.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) stepped in to help Zimmerman.

TCLF is a nonprofit organization that educates and engages the public to make our shared landscape heritage more visible, identify its value, and empower its stewards. It launched a campaign for Marabar

that designated the piece as one of its at-risk Landslide sites, and it gathered letters from landscape architects, architects, and journalists committed to seeing the work installed somewhere else. David Childs of SOM, who had worked on the original NGS campus, was among the supporters. To save the work, in 2021 the NGS agreed to relocate the sculpture and covered the cost of its removal.

The NGS suggested moving the sculptures to Washington Canal Park, but the idea was nixed by Zimmerman and Dave Rubin, landscape architect of Washington Canal Park. The artist explored several spots, ultimately settling on a location on the campus of American University. On the new site the positioning of the rocks was altered from its original iteration; here, the boulders are arranged in response to existing plants and trees. Zimmerman felt that with a new location, arrangement, and refurbishment the sculpture deserved a new title. She rechristened the piece Sudama

“Although reminiscent of Marabar, the new setting, and a thorough cleaning and repolishing of worn spots after 40 years made the piece look new and unique, so it needed a new title,” the artist said in an interview with TCLF.

In both locations the rocks are placed around a water element. Some faces of the rocks are left in their unaltered, rugged state, while others are cut and polished. These mirrored surfaces reflect their sur-

roundings, including other rocks, nearby buildings, and the landscape.

Both titles are references to the E. M. Forster book A Passage to India. In the novel, the author recalls a visit to the Barabar Caves in northeast India. In Forster’s dramatization, the name of the caves was changed to Marabar. Sudama is the name of another cave referenced in the text.

“Though we regret the loss of Marabar at its original location, we are pleased that

its creator, artist Elyn Zimmerman, with the support of National Geographic, retained the ability to control its reconfiguration and relocation to the American University campus,” TCLF’s president and CEO, Charles A. Birnbaum, said in a statement.

“Had TCLF not intervened beginning in March 2020, when the artist was resigned to the loss of one of her most important works, this acclaimed installation would likely have been demolished.” KK

Side By Side

Grimshaw Architects designs a sustainable and community-oriented office complex in Los Angeles.

Copper Topper

The Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, affectionately nicknamed St. John the Unfinished, remains without a spire, its south transept, and fully realized towers. Construction on the cathedral for the Episcopal Diocese of New York began in 1892 but only two-thirds of the church was ever completed. Still, the complex is making progress. The cathedral, which by some measures is the largest in the world, has just completed a three-year, $17 million renovation to repair its dome.

Ennead Architects, alongside Silman, Building Conservation Associates, and James R. Gainfort Consulting Architects, has refaced and restored the dome, which was a 1909 addition by Spanish American architect and master builder Rafael Guastavino. The rounded top was a provisional design element that spans the church’s four granite arches, occupying the location of an unrealized spire.

providing necessary thermal insulation and preventing water entry. To start, waterlogged insulation was removed, and tiles were allowed to dry out. The original tile work was evaluated and damaged pieces replaced with new, custom-made ones from Sandkuhl Clay Works. The design team specified the installation of sprayfoam insulation on the exterior surface of the structure to aid in thermal regulation.

Grimshaw Architects is looking to transform a parking lot in Los Angeles’s Chinatown into a bustling creative hub. The lot, at 130 West College Street, is slated to be a five-story, 233,000-square-foot development massed as two office buildings separated by a central atrium. The design, which will be structured in mass timber, places a strong emphasis on sustainable methods and systems as well as occupant wellness.

The proposal to reimagine the site—currently a vacant lot wedged between College, Bruno, North Alameda, and North Main streets in an underutilized section of the mixed-use neighborhood—has been submitted for entitlement review. Grimshaw developed the design with Riboli Family Wines and development manager Granite Properties.

Initial renderings of 130 West College show the two rectangular buildings standing side by side with a midblock courtyard. At street level, landscaping wraps the perimeter of the building where restaurants and shops can be situated. Above a wood-clad podium, two two-story rectangular volumes are layered and shifted in plan. Expansive terraces on the south-facing facade give the building its tiered appearance.

The program for 130 West College is reflected on its dynamic facades: Along the shorter faces, large spans of glass open to public-facing outdoor deck spaces. Meeting rooms and other spaces for more concentrated or private work are placed within the building’s core. Upper floors of the eastand west-facing elevations are fronted with a vertical grid of narrowed windows, while at street level timber slatting crowns the glass storefronts.

“The design vision is to create a vibrant and flexible exterior environment to accommodate different types of occupation across all levels of the development,” Andrew Byrne, managing partner of Grimshaw’s Los Angeles studio explained in a press release.

The project is an important one for Grimshaw, as its Los Angeles offices are just a few blocks away.

“With Grimshaw’s studio located just down the street from 130 West College, we feel very connected to the Chinatown neighborhood,” Byrne added. “It is important to us that our design for the building complements the local architecture and contributes to the vibrancy of the community.”

Though the buildings occupy much of the site, this does not close it off to the public: A landscaped plaza and raised outdoor terrace sandwiched between the two buildings create an inviting meeting spot for the entire community.

The proposed building prizes sustainability. As a firm, Grimshaw has “publicly committed to design and deliver socially and environmentally regenerative buildings and assets by 2030.” According to the firm’s website, it strives to achieve net zero carbon/net zero carbon–ready in all its design work by 2025. With all-electric systems, an array of photovoltaics, and the use of carbon-sequestering mass timber within the building, Grimshaw is making headway toward those decarbonization goals.

Another project goal promotes wellness among tenants. In addition to office space and collaborative work environments, the buildings would house bike storage, showers, and lockers.

“Today’s workers prioritize wellness and social engagement in their everyday experiences, so it is imperative to design the modern workplace with purpose and intention to draw people back into the office,” Byrne continued. “Our design for 130 West College will provide a robust mix of flexible workspace, desirable amenities, and outdoor space to support new ways of working.”

Alongside Grimshaw and developers, the project team includes SALT Landscape Architects, with Holmes Structures as the structural engineer, Buro Happold as the MEP engineer, and civil engineering work from Langan.

An entitlements review will be the next step for 130 College Street. The next design stage is anticipated to begin in early 2024. KK

Guastavino’s recognizable tile-work designs can be found all over New York City: at the Registry Room at Ellis Island, in the Oyster Bar in Grand Central, and on the underside of the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge. Guastavino designed the dome in the early 20th century as a temporary solution. Originally built in granite with a terra-cotta underside, the central dome defines an area known as the Crossing. The interior of the dome was never an ornate affair; rather, it was faced with concentric rings of tiles. In the years following its construction, several proposals circulated to replace the rounded volume with a completed Crossing, to be topped with a tower and spire.

As a structure built for short-term use, it wasn’t long after its completion that the dome required maintenance and structural upgrades. The landmark cathedral has been troubled with other issues for decades, as temperature fluctuations cause the dome to expand during hot weather and contract when the temperature drops. This seasonal (and daily) shift led to cracking and water infiltration. Beyond that movement, two fires caused damage within the church. In 2001 a blaze overtook the church gift shop and a part of the north transept, and in 2019 flames broke out in the crypt but were contained.

Renovation efforts have remedied these issues by improving structural integrity while

Working on the dome has required a careful balance between retrofitting for structural considerations and maintaining architectural quality and integrity. The tiled interior of the dome was recently restored and the new copper roof was added. This recent renovation is the first time in decades that the terra-cotta work has been visible. According to the Very Reverend Patrick Malloy, dean of the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, the tiles have been covered over by layers of “New York City soot, candle wax, and incense smoke,” blackening their appearance.

Ennead has a long history of working with St. John the Divine. The firm has overseen the continued upkeep of the building and property, collectively known as the Close. Its work has been consistently informed by the church’s mission and needs.

“Working closely to align with the cathedral’s priorities and concerns, we were privileged to have contributed to the enduring design within this magnificent landmark,” Charles Brainerd, senior associate at Ennead Architects, stated in a press release. “Our restoration harmonizes with the designs from a series of other architectural authors in the Cathedral’s century-plus existence, further enriching and honoring its history while reinforcing its integrity.”

Copper on the newly refaced dome matches the copper used on the cathedral’s choir and apse. The design utilizes a batten-seam copper roof construction, and the installation is laid out in a radial arrangement of rectangular copper sheets. The reddish-brown tone of the copper will patina to green over time, matching the color of the longstanding angel Gabriel statue on the apse roof.

The architects said that with the right care, the dome could last another 100 years. Whether a spire will ever rise atop the cathedral remains to be seen. KK

The International Mass Timber Conference brought together architects, contractors, fabricators, and foresters.

Progress and Possibility Deborah Berke Partners rebrands as TenBerke

At the International Mass Timber Conference, held at the Oregon Convention Center in Portland from March 27 to 29, a mood of celebration filled the air as a series of overlapping communities came together to acknowledge and plan for mass timber’s growing (if still small) presence in mainstream construction.

While some industries may be struggling to attain pre-COVID attendance levels, according to Arnie Didier, cofounder of the International Mass Timber Conference and COO of the Forest Business Network, the International Mass Timber Conference “had just under 3,000 this year, almost double our 2019 numbers.”

The packed exhibit hall was a case in point. “There’s clearly a tide raising all ships,” said Dean Lewis, who directs mass timber and prefabrication for construction giant Skanska USA and has attended the conference since its outset in 2016, when there weren’t enough booths to fill the space. Now, however, “in this hall we’ve got fabricators, installers, suppliers. You’ve got people that sell the equipment, people that sell coatings. There’s even a glue booth.”

The opening keynote was a panel discussion about equity in mass timber and beyond hosted by Portland developer and U.S. Green Building Council board chair Anyeley Hallová. “Real estate development in the United States is almost exclusively white,” Hallová said, citing figures showing that less than 1 percent of U.S. real estate developers are Black or Latinx, only 2 percent of licensed architects are Black (just 0.4 percent Black women), and 0.2 percent of construction companies are Black-owned. Yet the mass timber movement’s relative newness in America means opportunity. “We can’t wait for something to move forward before we make it equitable,” panelist Chandra Robinson, LEVER Architecture principal, said. “We have to start with equitable practices.”

A keynote the following day featured Vancouver, Canada, architect Michael Greene, who presented “Buildings of the Future: The Next Evolution of Wood.” Recent work by Greene, long among the profession’s foremost advocates for tall wood buildings and skyscrapers, includes 2020’s Peavy Hall for the College of Forestry at Oregon State University, which featured the first cross-laminated timber (CLT) rocking wall system in North America—it’s able to move and self-center during an earthquake.

The conference brought together a constellation of architects and academics. Members of Pritzker Prize–winning architect Shigeru Ban’s firm were here to promote its new book Timber in Architecture. Though Ban may be best known for experimenting with paper structures or pursuing humanitarian design solutions, he is also a timber innovator. “It’s not wood for wood’s sake,” cautioned Dean Maltz, partner at Shigeru Ban Architects. “He’ll pick the appropriate material for the appropriate place.” Yet the book makes a point of highlighting process and collaboration: It shows how to work with structural engineers and other partners to stretch wood’s material capabilities.

Lindsey Wikstrom was at the conference for an event celebrating her book Designing the Forest and Other Mass Timber Futures

A founding principal of Mattaforma and a professor at Columbia GSAPP, Wikstrom calls for architecture, material sourcing,

and forest management to be considered together as a single design problem. She said writing Designing the Forest was “about inspiring young architects to know their worth, that they have agency in a climate emergency to do work that matters.”

Wikstrom spoke at Mississippi, a mass timber building designed and occupied by Portland firm Waechter Architecture, which recently won a 2023 WoodWorks National Design Award in the Commercial/Mid-rise category from the Wood Products Council and Forest Business Network. (The latter produces the International Mass Timber Conference.) The building was completed in 2022, and its CLT was imported from Europe, firm founder Ben Waechter explained, because local providers couldn’t handle its extra details, such as a CLT core and stairs. But were it constructed today, Waechter explained, Mississippi’s wood would be locally sourced.

That growing regional capacity can also be seen in larger-scale projects like Portland International Airport’s renovation, currently underway and designed by ZGF Architects, which includes a mass timber ceiling of some 380,000 square feet, or nine acres. The wood was sustainably harvested within 300 miles of the airport and can be traced back to 11 landowners in Oregon and Washington.

How much market share is mass timber—and CLT in particular—gaining? According to separate research by IMARC Group, the global CLT market is projected to grow 12 percent annually from 2023 to 2028, reaching about 45.7 million square feet. “There was a lot of work done on the codes for the 2021 code and the 2024 code. A lot of those hurdles are being cleared now with time and expertise, whether that’s in commercial buildings, tall wood buildings, or modular affordable housing and residential,” Didier said. “You’re starting to see some of those switches as well.”

Even so, IMARC projects that by 2050, CLT would represent only about 0.5 percent of new urban buildings—a still very modest

share of the market. That’s why another key community at the International Mass Timber Conference, the timber industry, has retained a healthy skepticism.

“Most folks are more than willing to be part of the mass timber solution. But it’s not actually [in] a place yet that it’s driving demand,” said Joseph Furia of Portland’s World Forestry Center, a nonprofit devoted to sustainable forestry. “There are a lot of pain points in the system that are making it difficult to scale. How do we change that math? I run into people who are saying, ‘Where’s the beef? Show me that you’re actually going to be able to do this project faster, cheaper than conventional products.’”

The 2023 International Mass Timber Report, released at the conference, says that while mass timber can cost up to 15 percent more than conventional construction, the median project premium is actually less than 2 percent. And, the report noted, these figures do not consider mass timber buildings’ “additional potential to capture more in lease rates and lower tenant turnover” or to reduce construction time by up to 25 percent.

“We still have a shortage of builders and projects looking at mass timber because it has to be fabricated in a factory, and that’s a very different way of building that most of the construction industry is not familiar with,” explained Greg Howes, a partner at Portland- and Vancouver, Canada–based mass timber manufacturer Cut My Timber. “They don’t know how that will impact the labor cost—so you have a lot of bidding that’s happening based on minimal experience. But that’s inevitable in a market where it’s a relatively new project. Essentially, we have a very, very limited supply chain. But a lot more is about to come online.”

Brian Libby is a Portland freelance journalist who has contributed to The New York Times, Metropolis, Dwell, and The Wall Street Journal

New York–based architecture firm Deborah Berke Partners is now TenBerke. “The number ten speaks of multiples and unity, a reflection of the creative collective who form TenBerke,” the firm said in a statement. The firm sees the name change as better suited for its goal of designing for “meaningful and sustainable change.”

The firm also announced two new partners: Aaron Plewke, an architect and design leader, and Damaris Arias, the firm’s comptroller. Later this year, TenBerke’s hybrid-CLT residential buildings at Brown University will be completed, and in 2024 the firm’s expansion to the University of Arkansas Fine Arts Campus is slated to open. The Editors

News

Rossana Hu named chair of architecture at Penn

Rossana Hu of Neri&Hu has been selected by faculty at the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design to lead the architecture department as chair and tenured professor. Hu’s appointment follows that of Winka Dubbeldam, who has held the role since 2013. Hu is a cofounder, alongside Lyndon Neri, of Neri&Hu Design and Research Office, an office based in Shanghai.

Prior to cofounding Neri&Hu in 2004, Hu worked for Ralph Lerner, Michael Graves, and The Architects Collaborative in San Francisco. She holds a master’s degree in architecture and urban planning from Princeton and a bachelor of arts in architecture from the University of California, Berkeley.

Hu’s recent appointment is not her first role as a leader in architectural education. In addition to running her architecture and design practice, Hu has served as a professor and chair of the Department of Architecture in the College of Architecture & Urban Planning at Tongji University in Shanghai. She has previously held lecturer positions at universities across Europe, Asia, and the U.S., including the University of California, Berkeley; Harvard Graduate School of Design; Yale School of Architecture; and the University of Hong Kong.

Hu will begin her new position and join the faculty as a tenured professor starting on January 1, 2024. In the interim, Andrew Saunders, associate professor of architecture and director of the master of architecture program at Weitzman, will serve as acting chair of the Department of Architecture for the fall 2023 semester. The Editors

The Latest Vision for Midtown

ASTM Group, HOK, and, recently, PAU join forces in an attempt to solve New York’s Penn Station while keeping Madison Square Garden in place.

The wicked problem called Penn Station may, at long last, have a solution. Recently, a proposal by Italy’s ASTM Group and HOK emerged as some observers’ preferred option. On April 17, Practice for Architecture and Urbanism (PAU) joined the team. It is neither the optimal solution in all parties’ eyes nor the railroaded political fix that many feared, but it appears to value rail service and public space as its central priorities.

Penn Station and civic contention have been inseparable for six decades. The one point that commuters, architects, planners, activists, and oligarchs of real estate, entertainment, and sports agree on is that the station, the region’s infrastructural pain point, must change. Designed for fewer than 200,000 daily passengers and now subjecting over 600,000 travelers per day to conditions more suitable for scuttling rats than for civilized people, let alone the deities invoked by the oft-quoted Vincent Scully line, Penn Station is a magnet for revisions. On its site, the irresistible forces of design and transportation expertise meet an apparently immovable object: Madison Square Garden (MSG). With the Garden facing a Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) deadline toward the end of July, when the extension to its 2013 permit expires, a collision is inevitable. Yet the latest alignment of fixers could replace an unpopular scheme with one that is both infrastructurally desirable and politically possible.

The Narrative Changes, Again

The Penn Station situation has evolved rapidly since January 26, when a marathon event hosted by The Cooper Union offered several alternatives to the leading proposal at the time, the General Project Plan (GPP) associated with Governors Andrew Cuomo and Kathy Hochul, Empire State Development (ESD), and Vornado Realty Trust. That plan involved a combined station development and funding mechanism that included ten new commercial towers surrounding MSG and a neighborhood “blight” designation that opponents—particularly ReThinkPenn and the Penn Community Defense Fund, the event’s sponsors—viewed as spurious.

The event’s exchanges implied a Davidsversus-Goliath narrative that pitted community advocates and designers of bright, verdant, high-functioning civic spaces against private interests embodied by the Garden. MSG spans the tracks, its 261 supporting columns blocking redesigns that might improve circulation, admit daylight, and allow through-running rail service, which would convert the station from a terminal (where trains must reverse direction) to a more efficient station with two-way traffic. With an established preservationist narrative in full view but clumsily organized, one sensed that the public interest faced fierce headwinds.

A few weeks later, the winds changed. Vornado responded to the soft postpandemic commercial real estate market and high interest rates by putting the GPP on pause. This decision, combined with the impending July 24 expiration date for the special permit allowing MSG to continue current operations, opened a window for alternative plans. The three presented at The Cooper Union—PAU’s 2016 Penn Palimpsest, adapting MSG’s skeleton to create a new, light-filled hall; the Grand Penn open sta-

tion/park complex proposed by Grand Penn Community Alliance; and ReThinkPenn’s reimagining of the 1910 design, envisioned by Atelier & Co.’s Richard Cameron, that would update its materials, technologies, and seismic underpinnings to meet today’s codes—all would require the “World’s Most Famous Arena” to move, seeking the fifth address in its 144-year existence.

MSG Entertainment (MSGE) CEO James Dolan has framed that condition as a nonstarter. A comment by Executive Vice President Joel Fisher at a Community Board 5 (CB5) meeting on February 22, however, admitting the Garden might consider moving within the neighborhood if a suitable plan appeared, gave proponents of more ambitious visions a hint that the powers in charge might channel their inner Daniel Burnham and embrace plans with the magic to stir rail travelers’ blood.

On April 13, CB5 added pressure toward a move by approving a resolution by its Land Use, Housing & Zoning committee to give MSG three years to “pursue a permanent sustainable solution, including relocation.” There may be limits, however, to how much sway the special-permit decision allows the public sector over MSG, which owns the land, the building, and the air rights. The permit is not a lease, as some have described it, but a zoning provision that allows events with over 2,500 attendees; few expect it to expire outright, which would wreck schedules for the Knicks and Rangers and concerts scheduled far in advance for the 20,000-seat space. Likelier outcomes stand to include resetting a time frame and imposing conditions but not evicting the arena outright.

A “Mirror of a Mirror of a Ghost” Further complications appeared with the latest entry by Italy’s ASTM Group and HOK, covered in The New York Times on March 28, which is supported by former Metropolitan Transit Authority chairman and Port Authority executive director Patrick Foye and former U.S. Department of Transportation infrastructure adviser Peter Cipriano. This public-private plan would leave MSG in place, reclad it in aluminum and steel with a glass podium, wrap a new rectangular station around it, and replace the Theater at MSG (formerly Hulu Theater) with a new Eighth Avenue entrance. Further design and construction details will go public in June.

Though only three preliminary conceptual images were available by press time, ASTM Group/Halmar CEO Chris Larsen provided a statement: “Our team has developed a game-changing plan to fully deliver on Gov. Hochul’s new vision for a reimagined Penn Station that is iconic, spacious, accessible, and full of light and air, as well as improves the functionality for all users. We will continue to work closely with all stakeholders and community leaders to deliver a new Penn Station that uplifts the community and makes all New Yorkers proud while limiting risk to taxpayers through an innovative development approach.”

Another twist in the story arrived on April 17, when it was announced that PAU would join the ASTM-HOK team. PAU’s Vishaan Chakrabarti told AN that he was recently invited to view ASTM’s detailed plans.

“What I didn’t expect,” he said, “is at the end of the meeting, the ASTM leadership in-

vited me to join the team as a collaborating design architect.” After learning that ASTM and HOK had been working with various stakeholders for roughly a year, and finding their process “robust and deeply impressive,” he said was “gobsmacked” and lost sleep over the offer.

Decades ago, Chakrabarti had worked on a plan to move MSG to the back of the Farley Building, and as recently as the January event at The Cooper Union, he had been skeptical of other schemes that left the arena in place. It seems he found alignment between his values and those of ASTM, particularly the transit-function priority and the respect for Jane Jacobs’s four components of urban vitality: “density, mixed use, small blocks, and mixing old and new.”

In deciding to join the project, Chakrabarti said he “realized that it is better to light a candle than curse the darkness. I really feel that the team at PAU and I can make what is a very good project even better.” He continued: “It’s the most public plan I’ve seen that leaves the Garden in place.” It’s not surprising that Chakrabarti, who was director of City Planning’s Manhattan Office when Hudson Yards was rezoned in 2005 (and later joined SHoP Architects as its seventh partner prior to founding PAU), sees a public-private partnership as a way to save Penn Station; one challenge in keeping a new Penn Station from repeating the Hudson Yards experience, which combined large tax breaks and luxury condo development, will be for the ASTM team to separate public costs from privatized benefits and keep the two in balance.

In the initial press release for the merger, Chakrabarti said that the current scheme “promises a light-filled public transit hub similar to what PAU has always envisioned.” He pointed out that since ASTM and HOK have worked with MSG and Amtrak engineers as well as Vornado, the team is in a position to offer what PAU has advocated for years: “a comprehensive, full-block vision for how the public moves through that block on all sides of it, and whether there’s dignity to all of that movement; whether that dignity then spills over into a great neighborhood.”

The Metropolitan Transit Authority’s plan, Chakrabarti added, “has a mid-block component, but it doesn’t have the Eighth Avenue component,” as it would leave the theater in place. ASTM’s scheme reimagines the midblock area and both long sides and continues Penn Station’s relationship to the Farley Building, across Eighth Avenue. “McKim designed the Farley Building to be a mirror of [Penn’s] original Eighth Avenue facade, so it’s a mirror of a ghost,” he said. “We are interested in how [one could] make a contemporary mirror of the Farley Building; it’s the mirror of a mirror of a ghost.”

Another strength Chakrabarti sees is that “this plan is not contingent on the GPP. So it does not rely on the demolition of all of those buildings, and it’s not looking for a funding stream from the GPP; it is an independently funded, self-contained entity within the superblock.” One potential avenue for funding is that ASTM, the world’s second largest toll-road operator, could finance the reconstruction of Penn Station through a model similar to that used in airports. The flows of public and private revenues are among the variables that will re-

quire public scrutiny when ASTM’s detailed plan emerges in June.

ASTM and HOK separate the question of station and superblock redesign from capacity expansion: A separate Penn South plan would replace Block 780 (between 30th and 31st streets and Seventh and Eighth avenues) and require cut-and-cover construction, disruptive displacements, and likely eminent-domain seizures. “One of the things that I like about the ASTM plan,” he said, “is it tries to solve one big piece of the problem here, independent of the issues of Block 780 and the GPP.”

In response to ASTM’s plan, an MSGE spokesperson noted: “As we’ve said, we are always open to discussions. As invested members of our community, we are deeply committed to improving Penn Station and the surrounding area, and we continue to collaborate closely with a wide range of stakeholders to advance this shared goal.” The spokesperson also offered a lightly revised statement, dated February 9, dismissing calls for a move as “misguided [and] completely unrealistic,” citing ESD’s estimate that moving would cost the public $8.5 billion and claiming that “no realistic proposal or financial model for moving The Garden has ever been presented,” including the 2007–2008 discussion of moving to the Farley Building before Moynihan Train Hall opened. The statement further argued that the special permit, extended for a decade in 2013 but required of no other local stadium or arena, should become permanent.

Willing to Be Convinced

The impasse could be temporary, say observers who have held that a station worthy of New York is attainable only after the Garden departs and that MSGE underappreciates its own incentives to do so. Chakrabarti is among those reconsidering that position. “I never believed that the only way to fix Penn Station is to move the Garden,” he said, “but what I’ve said is I have yet to see a plan that really fixes the station with the Garden in place.... If you can do all that without the Garden moving, it’s obviously a lot less complicated.” Now the ASTM-HOKPAU team must address key challenges, including loading-access problems (existing service areas cannot accommodate large trucks, which often block sidewalk space) and the question of through-running, an efficiency upgrade recommended in various forms by ReThinkPenn and the Regional Plan Association (RPA), among others.

Putting transit ahead of components that have grown disproportionate in other projects, Chakrabarti says, is essential: Penn Station “is not a shopping mall; it’s not a casino; it’s not the base of an office building. It’s a train station, and it’s got to have a great public space around it, and if we do that the right way, it will pay for itself 100 times over.” Bringing American intercity rail up to global standards, he added, would also create climatic benefits such as reducing the need for short commercial air routes. Chakrabarti revealed that the detailed plan will also improve ADA access. “Between what happens in the midblock train hall between Two Penn and the Garden and the Eighth Avenue train hall, it will be a radically different experience and station. I think that will mean enormous things for this neighborhood.”

Instead of battles over MSGE’s intransigence, Chakrabarti continued, there could be “a moment of enlightened self-interest for the Garden, where if they prove that they’re going to be great citizens and cooperate, then some of the pressure the Garden gets publicly about some of these issues will dissipate.” Discovering that MSG personnel partnered with ASTM for over a year and that “no one in government had approached the Garden about moving whatsoever” catalyzed his realization that the immovable object might not move after all. “Design advocacy isn’t about getting 100 percent of what you want,” he summarized.

Tom Wright, president of the RPA, which has campaigned for major revisions to Penn Station since 2005 and called for its overhaul in the 2017 Fourth Regional Plan, has also had a change of heart about moving MSG—a shift due in part to a previous proposal by FXCollaborative and WSP for the MTA and Amtrak and in part to the ASTMHOK plan. “For a long time, we were in the position that the Garden needed to move to make way for a great train station at Penn,” he said. “We’ve always known there are two parts of this puzzle: One is the renovation of the existing Penn Station, and the other piece will be the expansion of Penn Station. Those are working on parallel tracks and not necessarily on the same time frame right now. We’ve looked at this for years and believe that Amtrak and the MTA and New Jersey Transit will, through a separate process, conclude that they are going to need to expand Penn Station, most likely to the south, to create more tracks and platforms.”

Expansion to accommodate new trains from the proposed Gateway tunnel under the Hudson River will need to undergo National Environmental Policy Act review as well as negotiations with local residents, businesspeople, and advocates, who may find the project unacceptably disruptive.

Block 780 presents complications, as Penn South plans may include two levels of tracks and platforms beneath it, Wright noted, “essentially condemning the entire block.” Planning for the community that must endure the renovation and expansion processes, Wright adds, is thus a third and indispensable aspect of the overall effort.

In the renovation component, FXCollaborative’s design convinced Wright and colleagues that a better station could be created by eliminating one of the floors within Penn Station and relocating Amtrak’s back-office operations without moving MSG. “It would allow you to widen the concourses and create higher headroom,” Wright said. “We started to believe that it showed that you could create a good Penn Station without moving the Garden. And quite frankly, if you can do it without moving the Garden, you should do it without moving the Garden, because moving the Garden is going to be extraordinarily expensive.”

ASTM’s plan improves on FXCollaborative’s, Wright added, by removing the theater and opening the Eighth Avenue side: It removes many (though not all) columns from platforms, expanding egress at notorious pinch points. Seventh Avenue access, widened concourses, and exits and entrances remain to be addressed when the full plan is released.

Extricating design and planning considerations from financial details has been a conceptual challenge for both insiders and the public. The ASTM plan is “now being talked about as an alternative to the GPP, when in fact these are different plans doing different things,” Wright said. The GPP represented New York State’s planning process (as opposed to a city rezoning) to determine where density should go and how to coordinate public and private-sector investments so that “the state would have the ability to benefit from some of the increased proper-

ty values and use those revenue streams to help pay for the portion of the infrastructure that it needs to pay for.”

The general agreement on the Gateway tunnel is that the federal government would pay for 50 percent of it and New York State and New Jersey would split the remaining costs at 25 percent each, according to Wright. The GPP mechanism would allow the state to recoup some of its multibillion-dollar Gateway commitment. “If the GPP goes away, New York State will have to come up with other revenue sources to pay for its piece of Gateway,” he said. Whatever happens with Vornado’s office towers or any other parcels, Wright added, must still undergo public review, including a Public Authorities Control Board vote. “The GPP gave nobody any as-of-right development.”

“I think the GPP should be put on a shelf,” Wright continued. The focus, he said, should return to other questions: “What do we want Penn Station to look like, and how is it going to function, and are we going to need to expand it and, if so, how does that work and how does that connect with the renovation of Penn Station? And once those issues have been brought forward and understood, then I think the public understands what it’s getting for the money, and then it’s a different conversation. But it still needs public approval.”

ASTM’s proposal is “fully integratable” with these mechanisms, he added, and has benefited from proceeding collaboratively rather than “shooting in with a kind of a priori deus ex machina plan.”

As for the other plans that propose relocating MSG, “there’s not much realism in those conversations” about the economics of the different components of the work required,” Wright offered. Among other obstacles, he added, “nobody working in Washington believes that there will be federal funding to contribute to moving Mad-

ison Square Garden.” Although ESD’s $8.5 billion figure may not hold up, Wright estimates that at least $5 billion in costs would be borne by New York State, “and that becomes competition for other infrastructure needs and funding. If the Garden was interested in moving and came up with a proposal with one of the other major real estate developers in the neighborhood and said, ‘This is something we want to do,’ then I think it would make sense for the city and the state and Amtrak and others to all engage with them and talk about that. But there’s been no indication whatsoever that they’re interested in that.”

An MSG move remains a must for many citizens for many reasons, including the illogic of a private entity having so much leverage over a public process and an essential public good; the ways the organization has treated its critics and legal opponents; the rankling vision of hardball obstructionism rewarded; and the tabula rasa that its move could create for broader expansion of public space. Beyond those objections also lie visions of a newer, better, more profitable MSG at a different site, a potential outcome that might eventually attract the company’s attention. (Knicks fans, in particular, may take note of how new quarters have sometimes breathed life into snakebitten sports franchises.) MSG’s opponents have even offered designs for offsite facilities.

With the clock ticking on the Garden’s permit extension, there stand to be complications on the path to solving Penn Station.

For the present, however, the basic proposition, according to Chakrabarti, is: “If you accept the fact that MSG is not going to move, how do you make a great public station at Penn? What we’re working on now with ASTM and HOK is the way to address that problem.”

Tripartite Timber

Construction finishes on a CLT pavilion designed by Rice Architecture students.

Despite being centrally located in Houston, Rice University falls along a major bird migration route, making it one of the most biodiverse universities in the country, with one of the biggest bird species lists of any campus in North America. The Harris Gully Natural Area is a restored watershed within the Rice campus that includes several microhabitats for the migrating birds, including prairies, open woodland, and dense shrubland. The Mass Timber Pavilion, an observation deck immersed within the landscape, represents a small step toward the long-term management of this ecosystem.

The pavilion itself is an abstract object, conceived and sited in the picturesque tradition. Like the ruin of a small temple, it invites and accommodates nature around it. In its simplicity, indeterminacy, and openness, it insinuates the lightness of touch that should guide the stewardship of Harris Gully in the future.

Made of CLT sourced from southern yellow pine, the pavilion is a carbon-negative structure and an essay on the possibilities of this sustainable construction technology. A didactic design, the building showcases the CLT panels in their purest form, like a giant piece of furniture that conveys the logic of its assembly. The immediate way in which the material is presented underlines its structural versatility, featuring CLT serving as roof, pillar, and capital.

The project was designed in Rice associate professor Jesús Vassallo’s wood seminar by a team including graduate students Pouya Khadem and Lene Sollie in collaboration with structural engineer Tracy Truc Huynh. Under Vassallo’s supervision, the students developed the construction documents and took the project from conceptual design all the way through permitting. Funding for the project was obtained through a federal grant from the U.S. Forest Service, with additional funds provided by generous gifts to the School of Natural Sciences and the Rice Arboretum Committee.

Jesús Vassallo is a Spanish architect and a writer and professor at Rice University.

Pouya Khadem is a recent graduate of the MArch program at Rice Architecture and currently works at SCHAUM/SHIEH in Houston.

Lene Sollie is a recent graduate of the MArch program at Rice Architecture and currently works at Dark Arkitekter in Oslo.

Tracy Truc Huynh is a structural engineer with degrees from Rice and Princeton and currently works as an expert in decarbonization of the built environment at RMI.

Gold Among Green

In 2012, the Hoge Veluwe National Park, the largest nature reserve in the Netherlands, launched a competition for the design of the park’s new visitor center. The brief contained a surprising stipulation: Architects were kindly advised not to submit structures clad in wood. To many this must have been strange, since a facade mirroring the eco-identity of the building’s context, possibly even sourcing timber from the immediate vicinity of the building site, seemed to make a lot of sense. Yet that very environment was the reason for the provision: Previous wooden structures had deteriorated quickly in the park’s humid forests and required a large amount of maintenance to be kept free of moss and algae. The client, driven by a pragmatism often found in those whose relationship with nature extends beyond the romantic, simply wished to avoid costly upkeep of the structure intended to be the last one built within the park for the next 50 years.

Unsurprisingly the winning design, a submission titled Park Pavilion and designed jointly by Dutch offices Monadnock and De Zwarte Hond, does not have a wooden facade. Instead, the exterior, a dynamic composition that succeeds in making the building appear smaller than its actual size (about 35,000 square feet), features light yellow bricks and gold-colored aluminum mullions that make it stand out from its green surroundings. The clear separation of building and nature mirrors two notable predecessors located nearby: a hunting lodge designed by Hendrik Berlage and the renowned KröllerMüller museum by Henry van der Velde. All three buildings utilize a contrast in materiality and geometry to carve a sanctuary out of

the wilderness. Further, all three also evoke an interpretation of sustainability that favors durability over renewability

Now, three years after construction has finished and about a decade after the design competition was announced, Park Pavilion serves as a case study about the shifting tone of the debate around sustainability and ecology. Enough time went by between conception and inauguration for opinions to significantly change: Do we consider what seemed acceptable and sensible in 2013—a building made of brick and aluminum inside a nature reserve—to still be so in 2023?

Perhaps not, Job Floris, cofounder of Monadnock, told AN: Today, both client and designer would probably push for a more conspicuously nature-inclusive approach. However, he adds, that push would reflect not only an advanced understanding of the impact of buildings on the environment but a change in taste as well: Buildings that wear their modest carbon footprint on their sleeve are en vogue at the moment.

As an example, consider the resurgence of interest in using stone in construction, as explored in The New Stone Age, a 2020 exhibition curated by the London-based office Groupwork. The embodied carbon of a load-bearing superstructure in natural stone, the show claimed, is as much as 90 percent lower when compared with steel or concrete alternatives, depending on the type of stone and the distance it needs to be transported. This means that, for instance, load-bearing stone facades might be the most sustainable option in some cases—especially if we make sure the buildings they support last a very long time.