ITALIA

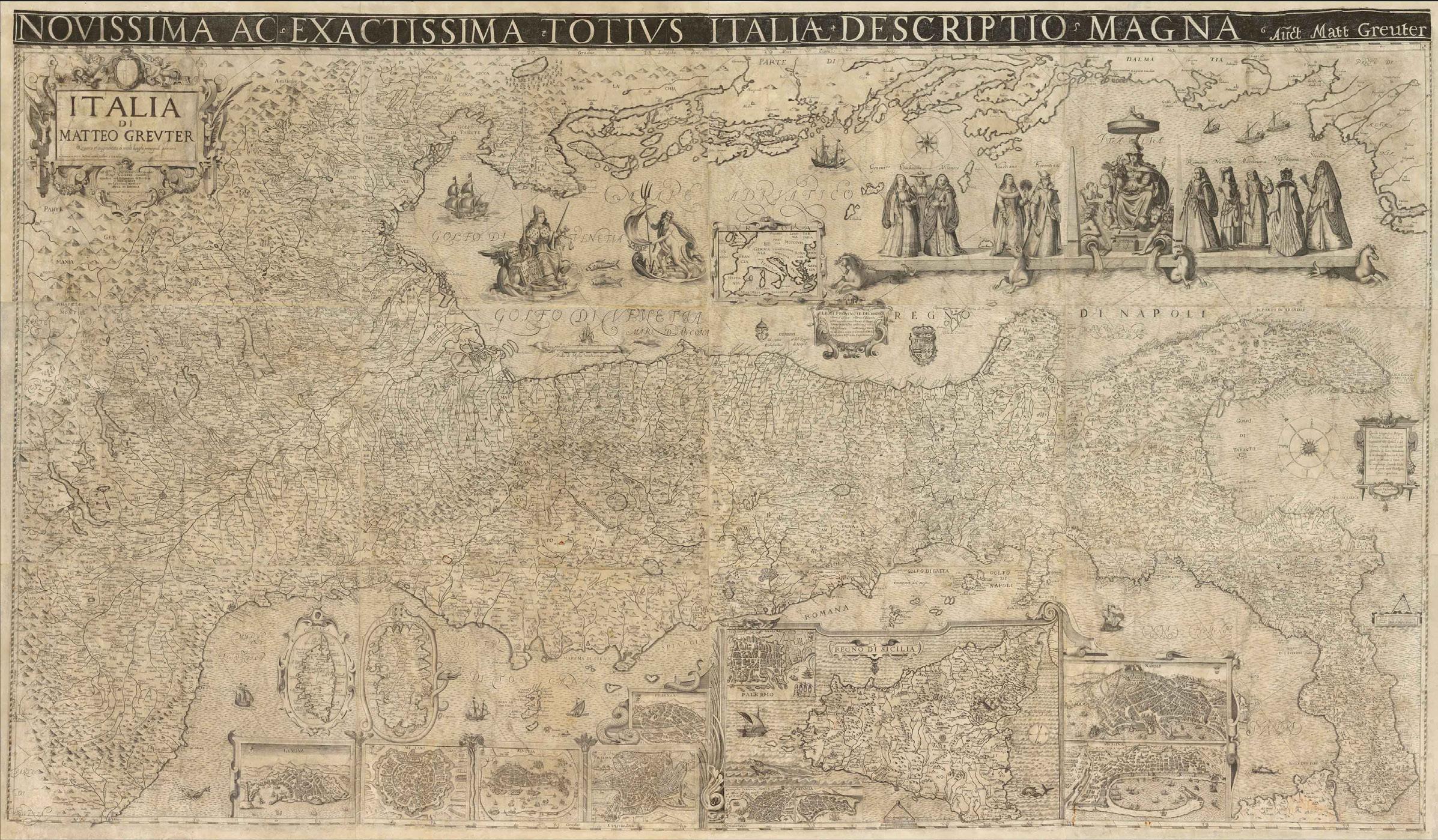

STEFANO SCOLARI (c. 1612-1691), after MATTEO GREUTER (1564-1638)

Novissima ac Exactissima Totius Italia Descriptio Magna . . . / Italia di Matteo Greuter Revista et augmentata di molti luoghi principali MDC. LVII

Engraved map

Venice: Stefano Scolari, 1630 (1657)

87 1/2” x 47 1/2” sheet

$145,000

Monumental wall map of Italy in 12 sheets, first published by Matteo Greuter in Rome in 1630 and here, the second publishing by Stefano Scolari in Venice in 1657. At the time of its publication, the map was the largest map of Italy in existence and the present map is the only known example that includes the title above the map with white letters on a black background, an unusual and visually striking element.

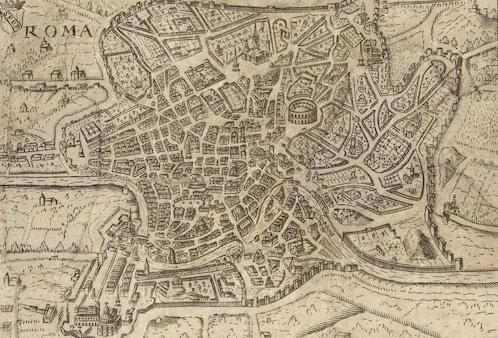

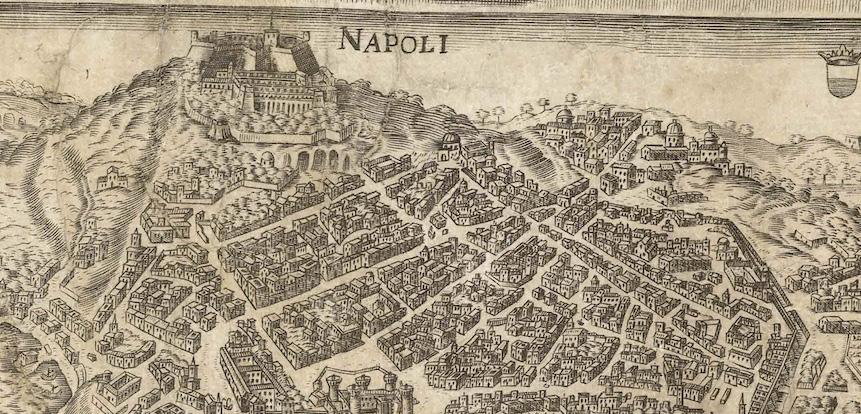

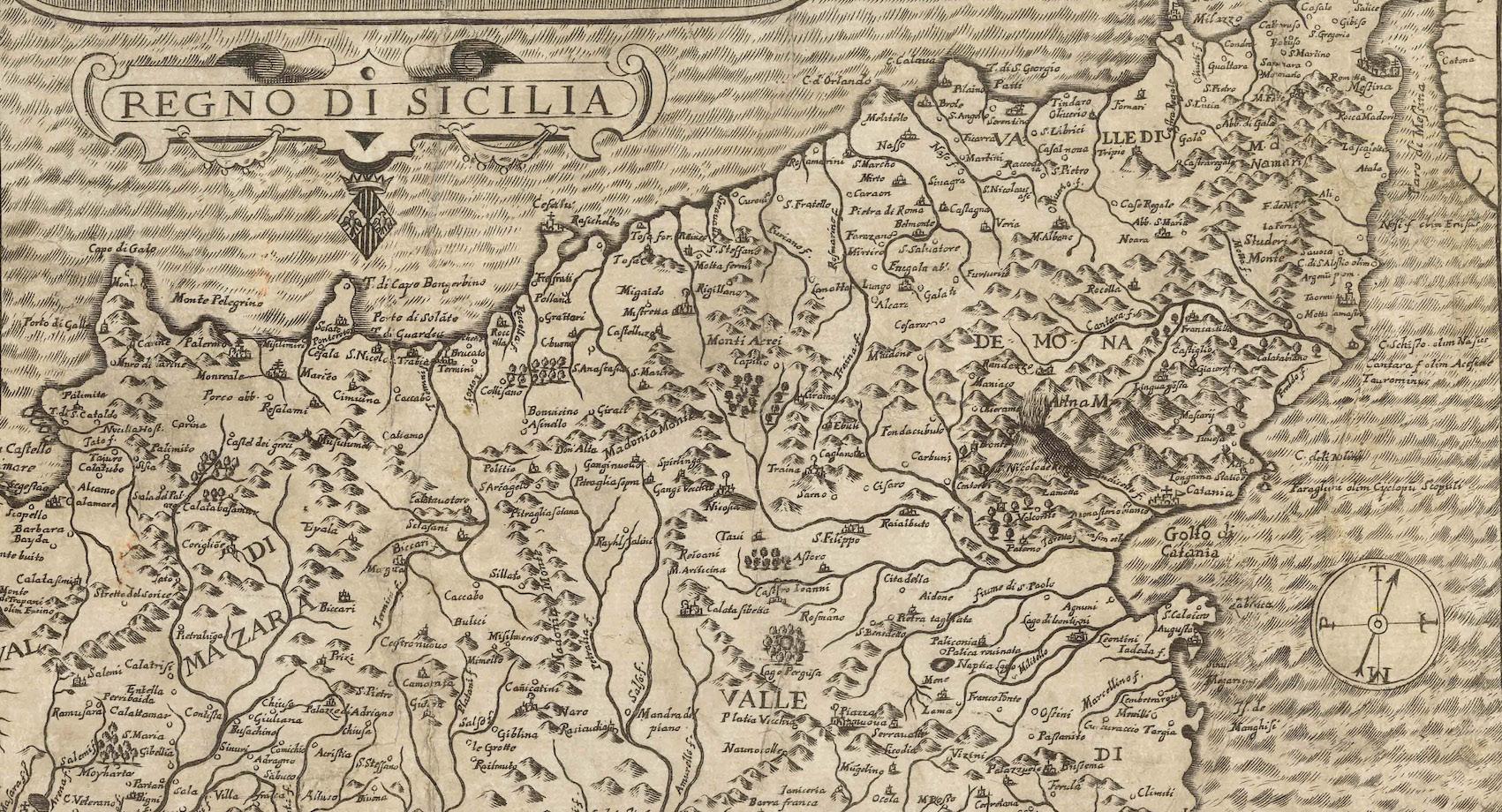

Atypical to most maps of Italy, the map is oriented with the northeast at the top. The map notes, “Questo Geografico Disegno è Voltato à traverso per la Comodità del Lettore.” In English, “This geographical design is turned sideways for the comfort of the reader...” Greuter and Scolari spare little in cartographic detail. The interior is teeming with markings for hundreds of villages and towns. The infrastructure is not denoted by a single symbol — as was common in maps of this scale — but painstakingly details the size and type of church the locale has, the scale of the settlement, provincial and familial coats of arms, and dotted lines to separate political entities. Certain cities have recognizable features to modern eyes, including St. Peter’s Basilica and the city walls of Rome. Hills and mountains are also marked, some with unique features such the cavernous hole depicting Mount Vesuvius near Naples.

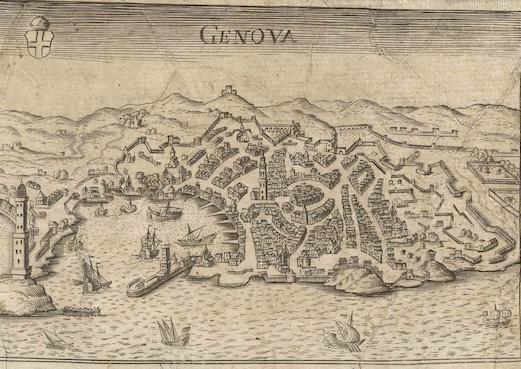

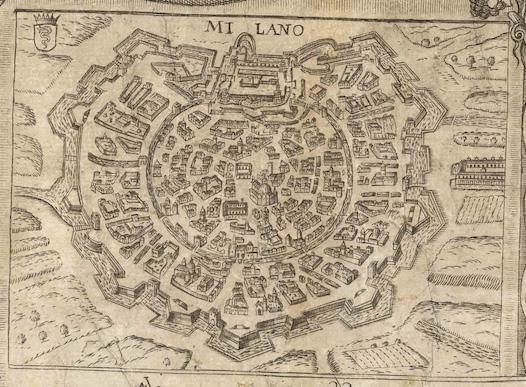

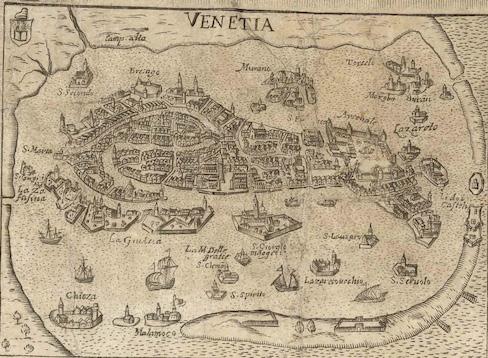

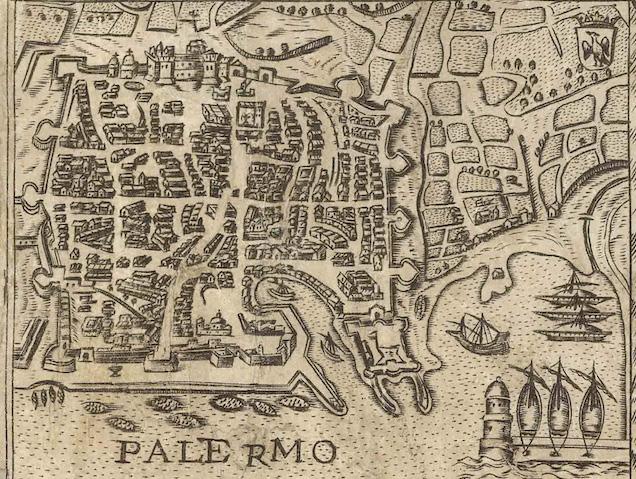

The longitudes shown are relative to the Cape Verde, and islands, cities, and landmarks are printed in Italian. The three major islands of Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica are shown separately as insets. Views of major Italian cities are also shown, including Genoa, Milan, Venice, Rome, Florence, Palermo, Syracuse, Catania, Naples and Messina. An inset map of Europe rests in the Adriatic Sea.

In the Gulf of Venice, a hand emerges from the waves to point to a scale in Venetian miles. It is protected by a Venetian vessel and menaced by a hungry sea-bear. Just below the main allegorical vignette (discussed below) is a cartouche with the twelve southern provinces of the Kingdom of Napoli. This cartouche is flanked by coats of arms. Many ships are adrift in the waters all around Italy.

In the Mediterranean, to the south of the peninsula, a cartouche houses a brief text explaining the orientation of the map. The decorative but not ostentatious strapwork on this cartouche is echoed in the title cartouche in the upper left, as well as in the inset maps and views below. There is also a compass rose with the directional winds labeled. Slightly farther east is another scale measuring twelve miles and topped with dividers.

The title cartouche contains a dedication to Signore Gioseppe Sauoldo, a judge of the College of Brescia. Brescia, a province and city in Lombardy, was then under Venetian rule. Sauoldo was also the consigliere, or

advisor, to the Elector and Duke of Bavaria. In 1657, when the map was reissued, this was Ferdinand Maria, who ruled Bavaria from 1651 to 1679. Ferdinand needed the advice of men like Sauoldo, for he was only 15 when he ascended to the position of Elector. He was officially crowned in 1654 and is known for modernizing the Bavarian army and introducing the first Bavarian local governmental code.

Greuter’s map of Italy must have been popular, as it was reissued several times over the course of nearly two centuries. First, it was re-released in Venice by Stefano Scolari in 1657; then, by Pietro Tedeschi and Giuseppe Longhi in Bologna in 1676; and then, by Domenico De Rossi in Rome in 1695. Finally, Tedeschi and Longhi released another example in 1713.

ALLEGORICAL FEATURES

The rich allegorical figures at the top right are yet another visual treat of this map. These center around a female representation of Italy, seated on the throne, with the Po and Tiber rivers at her feet. On either side are the trappings of civilization, including armor, a vase, an artist cherub, musical instruments, and crowns. To the left and right, Italy is flanked by five costumed ladies representing the various provinces of the region. On the left, the Northern cities of Genoa, Lombardy, and Milan stand separate from Venice and Florence. Milan and Lombardy were firmly under Spanish imperial control, while Genoa was a powerful but dependent ally, whose wealth helped fund Spanish wars in exchange for protection and prestige. Their subjection is evidenced by their conservative fashion. Donna Milanese even sports a ruff — a stiff pleated collar that had fallen out of vogue in Europe at large by the early 17th century but lingered for decades after in Spanish clothing. To the right are Rome, and two women from Noto and the Amatrice region (whose physical depiction is likely referencing a late 16th century series of ancient regional costumes). Donna Matriciana lacks the torch and spool she is meant to hold. The woman from Naples stands with her back to the viewer (and perhaps to Italy herself), likely representing the period of social and political turmoil in the region. Naples was similarly under Spanish rule throughout the 17th century, but the Neapolitans voraciously supported the imperial army, crushing their economy and increasing public debt fourfold. Sicily — the last depicted region of the Spanish Empire — is outfitted with a mantilla

veil, standing furthest from the personification of Italy.

To the left of these women is Neptune with his trident. Interestingly, Neptune floats in a shell filled with wares and propelled by a sail as opposed to riding on a chariot drawn by horses. By the 17th century, Italy’s overwhelmingly Catholic population had conflated depictions of the Greek Poseidon with the Roman Neptune, but Greuter has made the choice to differentiate the two, divorcing Neptune from association with equine forms or the god Consus, protector of grain and most recognized by horse iconography. This decision was likely to highlight Venice’s mercantile success, but has nationalistic undertones and suggests a cultural purity, as Consus was the deity who urged Romulus to abduct and rape the women of Sabine — a contentious period of Roman hisotry that incorporated the region of present-day Umbria. The figures are thrown into further theological tension, as the Roman goddess Justitia sits to the left of Neptune, draped in ermine and sumptuous clothes. She holds the scales of justice and a sword, but additionally sports the corno ducale, a horn-like bonnet made of brocade and embellished with gold and gems, invoking the Doge of Venice. Next to her on the decorative shell in which she floats is a lion holding a book which proclaims, “Pax Tibi Marce Evangelista Meus,” translating to “Peace be with you, Mark, my evangelist.” According to legend, these words were uttered by an angel who appeared to St. Mark in a dream after landing on an island in the Venetian lagoon. The phrase was understood as a prophecy that the saint would find rest, devotion, and honor among the Venetian population.

The prophecy was fulfilled eight centuries later, when Saint Mark’s body was smuggled out of Alexandria in a shipment of pork and vegetables. The most famous church of the city is the Cathedral Basilica of St. Mark, built to house his remains, and double as the chapel of the Doge of Venice.

Together, the decorative elements of Scolari and Greuter’s map dramatize a broader ideological struggle: Catholic piety is put in conversation with Roman dieties, republican virtue overlaps with imperial ambition, and regional pride sits uncomfortably against the backdrop of foreign rule. In symbolically portraying these contradictions, Scolari and Greuter’s map goes beyond charting geography, and becomes a visual argument for Italy’s fragmented identity, torn between a classical past, papal authority of their present, and the pressures of emerging nationalism.

EDITIONS & RARITY

Greuter’s original Rome edition from 1630 does not survive but two later states are known: a 1640 (Bibliotheque National de France) and a 1647 (Mediateca di Santa Teresa di Milano). Scolari’s Venice edition of the map survives in very few recorded examples. These include examples in the Biblioteca Nazionale di Firenze (Fondo Palatino) and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. There is also a privately-owned example in Rome.

GREUTER & SCOLARI

The Strassbourg-born Matteo Greuter (Matthaus, 1564–1638) published many religious and mythological scenes throughout his life, the antithetical nature of which is not unsurprising, as Greuter converted to Catholicism in middle-age. He first moved to Avignon with his three children, and in 1603, settled in Rome and opened a shop in the Piazzadi San Marcello. His first year in Rome afforded him success, evidenced by his 1604 petition for a 10 year papal privilege (a copyright, essentially) on a blanket statement of “engravings.” The penalty for violation was no pittance. A fine of 500 gold ducats (today, roughly $180,000) was to be divided between Apostolic Chamber, Greuter, the accusers, and the judges. His precautions were warranted, as he quickly rose to prominence and is most well-known for the technological feat of his grand twelve-sheet map of Italy, considered one of the finest ever produced of the country. Greuter produced countless maps of Italian cities and is known to have engraved several globes for a variety of patrons, including Cardinal Scipione Boghese, Pope Paul V, the Accademia dei Lincei, and Pope Urban VIII. He additionally created the plates for Galileo’s Macchie Solari [Letters on Sunspots] (1613) using a combination of engraving (maneuvering a tool to carve) and etching (utilizing acid to corrode the surface of the metal) to develop a sophisticated variation in tones that mimicked the smoky, ephemeral sunspots Galileo described.

Greuter was strongly influenced by his Dutch counterparts, especially Willem Blaeu, whose globes he diligently updated. Stevenson notes that during the last years of his life, Greuter went on to produce a 1635 celestial globe and several reduced-size globes. Following Greuter’s death in 1638, Giovanni Battista Rossi and, later, Domenico de Rossi, released subsequent Greuter globes. A number of these are detailed in Elly Dekker’s book Globes at Greenwich and Stevenson’s Terrestrial and Celestial Globes

Stefano Scolari (c. 1612–1691) was known primarily as an illustrator and would be among the first engravers to devote his activity entirely to illustrated editions. His work included pieces drawn and engraved by himself, images produced in collaboration with other artists and editors, and the reproduction of already published copperplates, such as this re-issue. Originally from Brescia, Scolari practiced his trade in Venice. His shop, in San Zulian under the sign of the Three Virtues, was one of the best known in 17th century Venice.

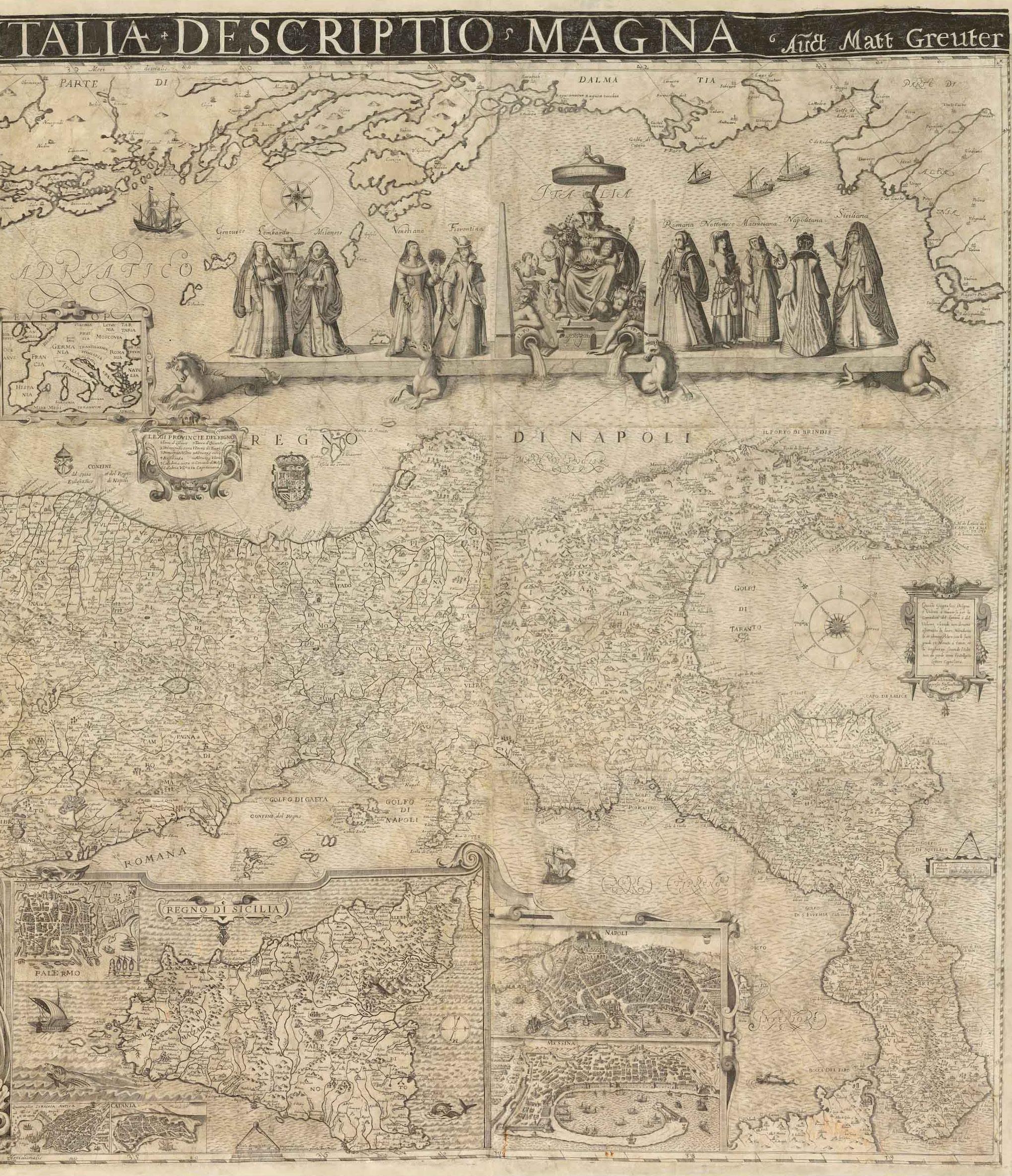

THE MOST IMPORTANT MAP OF ITALY FROM THE 16TH CENTURY

Paolo Forlani (1560-1571) & Giacomo Gastaldi (1500-1566)

[Italy] [Ded. to Carlo Vicentino] Al Molto magno. et exccellmo Sigor. Carlo Vicentino sup sigor sempre ossexmo. Tra Ie piu belle e plu perfette opera di M. Giacomo Gastaldi prestantissimo Cosmografo, alcuna no e’ che mai s’habbi possuto coparare alla sua Italia .. . Di Venetia il pm« dell Anno MDLXVIIII Paolo Forlani Veronese.

Engraved map Venice: 1569

22” x 31 3/16” sheet; 33 1/2” x 42 3/4” framed

$28,000

A highly important and influential map, the apex of Gastaldi’s cartographer’s vision of Italy, and certainly one of his great masterpieces. This is Forlani’s derivative of Gastaldi’s great map.

The peninsula is shown with great detail and accuracy, a broad panopticon sweeping diagonally across the map from the alpine lakes in the north to the Strait of Messina in the south, with seas adorned with elegantly engraved ships. It is based on Gastaldi’s earlier Italian regional maps supplemented with the best contemporary sources. While it bears a resemblance to the southwestern plate of his monumental four sheet map of southeastern Europe, the image had been revised and enlarged. Although Gastaldi, originally of Pied-

mont, had been working as a cartographer in Venice since 1539, this is his first large-scale map of Italy. One of the most influential maps of the sixteenth-century, Roberto Almagià referred to it as “truly one of the milestones in the evolution of the cartography of Italy” (see Karrow, p.236).

Giacomo Gastaldi (or Giacopo; ca. 1500–1566) was undoubtedly the greatest master of Venetian cartography. Having been established in the city for two decades, by the late 1550s Gastaldi was devising the largescale monumental masterpieces that would confirm his legacy: his colossal maps of Asia, Europe and Italy. “Cosmographer to the Venetian Republic, then a powerhouse of commerce and trade. He sought the most up to date geographical information available, and became one of the greatest cartographers of the sixteenth century” (Burden). Giacomo Gastaldi was, and styled himself, ‘Piemontese’, and this epithet appears often after his name. Born at the end of the fifteenth or the beginning of the sixteenth century, he does not appear in any records until 1539, when the Venetian Senate granted him a privilege for the printing of a perpetual calendar. His first dated map appeared in 1544, by which time he had become an accomplished engineer and cartographer. Karrow has argued that Gastaldi’s early contact with the celebrated geographical editor, Giovanni Battista Ramusio, and his involvement with the latter’s work, “Navigationi et Viaggi”, prompted him to take to cartography as a full-time occupation. In any case Gastaldi was helped by Ramusio’s connections with the Senate, to which he was secretary, and the favourable attitude towards geography and geographers in Venice at the time.

Paolo Forlani (fl. 1560-1571) was perhaps the most prolific producer of maps in the mid-16th century, and largely responsible for diffusing advanced geographical information to other parts of Europe. He was responsible for some of the most beautiful and visually appealing maps of his time, following in the footsteps of his great colleague Giacomo Gastaldi, and was a Venetian engraver and publisher of many significant maps and charts in the period of the Renaissance. It was in Italy, and particularly in Venice, that the map trade, which was to influence profoundly the course of cartographic history, was most highly developed during the first half of the 16th century. Venice was the most active port in the world, and successful trading expeditions necessitated accurate maps. Venetian ships made regular trading voyages to the Levant and into the Black Sea, to the ports of Spain and Portugal, and along the coasts of Western Europe. In the 15th century the city had already become a clearing-house for geographical information, and the development of cartography in the city was further impelled by the accomplishment of Venetian printers and engravers. This beautiful map was engraved by Ferrando Bertelli (fl. 1556-1572), one of the most prolific of Venetian map publishers and engravers, who also sold composite atlases and worked at various times with other great names in Venetian cartography.

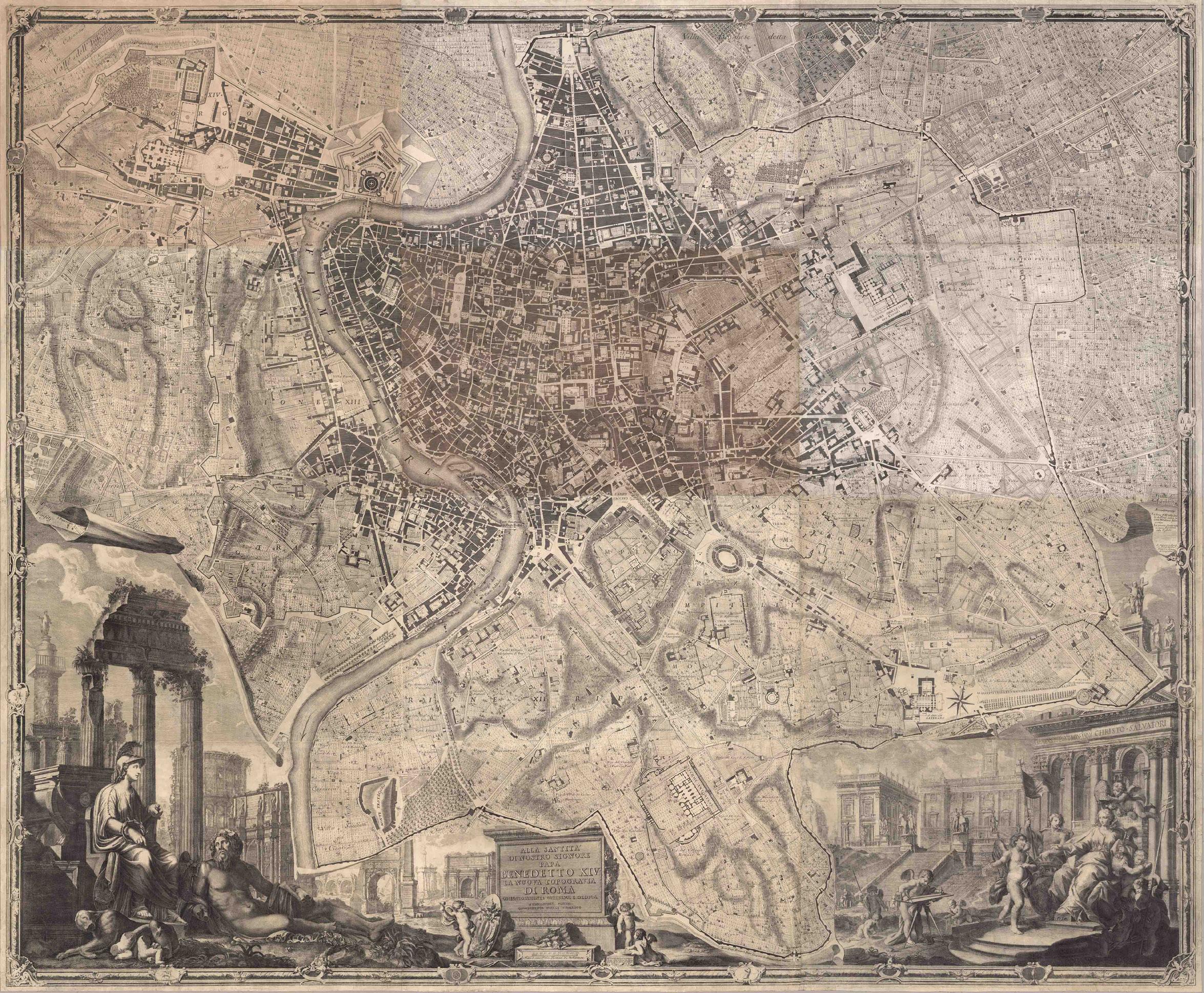

THE DEFINITIVE MAP OF THE ETERNAL CITY USED BY OFFICIALS FOR THREE CENTURIES

Giovanni Battista Nolli (1701-1756)

Nuova Pianta di Roma data in Luce da Giambattista Nolli l’anno 1748

Engraved map

Rome: 1748

70 ⅞” x 110 ⅝” sheet

$38,000

A celebration of both ancient and modern Rome, Giovanni Battista Nolli created Nuova Pianta di Roma… to showcase the epicenter of Italy. Published in 1748, Nolli’s map exhibits nearly eight square miles of the city, and some surrounding terrain. Through this map, Nolli provided a highly important record of Rome in the midst of the city’s heyday. Rome during the mid-eighteenth century was a mecca for cultural institutions and blossoming scientific ideas.

Initially born in the province of Como in April of 1701, but later moving to Milan as an adult, and subsequently Rome, Nolli spent his time in Italian cities initially working as an architect. Nolli spent time working on the churches of Sant’Alessio and Santa Dorotea in Rome before providing his remarkable contributions to the field of cartography. Rome, being an independent papal-state during the 1700s led to generous and frequent contributions by the popes – some of the most important patrons of the art. Pope Benedict XIV commissioned Nolli to create this map of Rome as a means to establish clear borders of the rione, the different regions in Rome at the time.

Leonardo Bufalini, a cartographer who predated Nolli, had created the most celebrated and important map of Rome until Nolli’s Nuova Pianta di Roma… Nolli built off Bufalini’s pre-existing revolutionary map that was the first large-scale map of Rome since antiquity. Even more notable, Nolli’s map was drawn to scale. Moreover, Nolli’s map reflects the advancements that Bufalini had made, but Nolli built upon these previous contributions to go a step further.

Comprised of twelve copperplate engravings, Nuova Pianta di Roma documents significant streets, churches, palaces, piazzas, and even drains and cemeteries in the city. The process for Nolli took over ten years to complete. Beginning in 1736, Nolli began surveying the city. Then and now Nolli’s map of Rome was majorly celebrated for its accuracy and thoroughness. It is considered the first scientific rendering of Rome.

On either side of the bottom of the map, Nolli created two large cartouches that are allegorical scenes. On the left side of the map are Minerva and Tiberinus – Roman classical figures each with large, individual significance. Both Minerva and Tiberinus are tied to Rome’s identity, values, and geography, making them critical additions to any map of Rome, especially one done in the eighteenth century at the height of neoclassicism. Minerva, as the Goddess of wisdom, represents strategy, warfare and ghe arts, as well as law, governance, justice and culture. In cartography, Minerva is often symbolic of the protector of cities and the guardian of civilization. Tiberinus, the Roman river god of the Tiber, signifies Rome’s geography and lifeblood. Together, the pair exemplify the long-standing cultural legacy of Rome.

On the bottom right side of the map is an enthroned woman surrounded by cherubs. On the temple behind her there is an inscription that reads: “DIVO. CHRISTO. SALVATORI,” Latin for “To the Divine Christ the Savior," showcasing the importance of the Catholic Church in Rome. Notably, this inscription also identifies the structure as the Archbasillica of Saint John Lateran – the cathedral of Rome and the official ecclesiastical seat of the Pope. At the center of the map, Nolli honored Pope Benedict XIV by dedicating this map to him.

Giovanni Battista Nolli embarked on a mission not solely to showcase Rome’s geography, but also to conceptualize the city through its most important ideals – religion, neoclassical thinking, and Enlightenment practices.

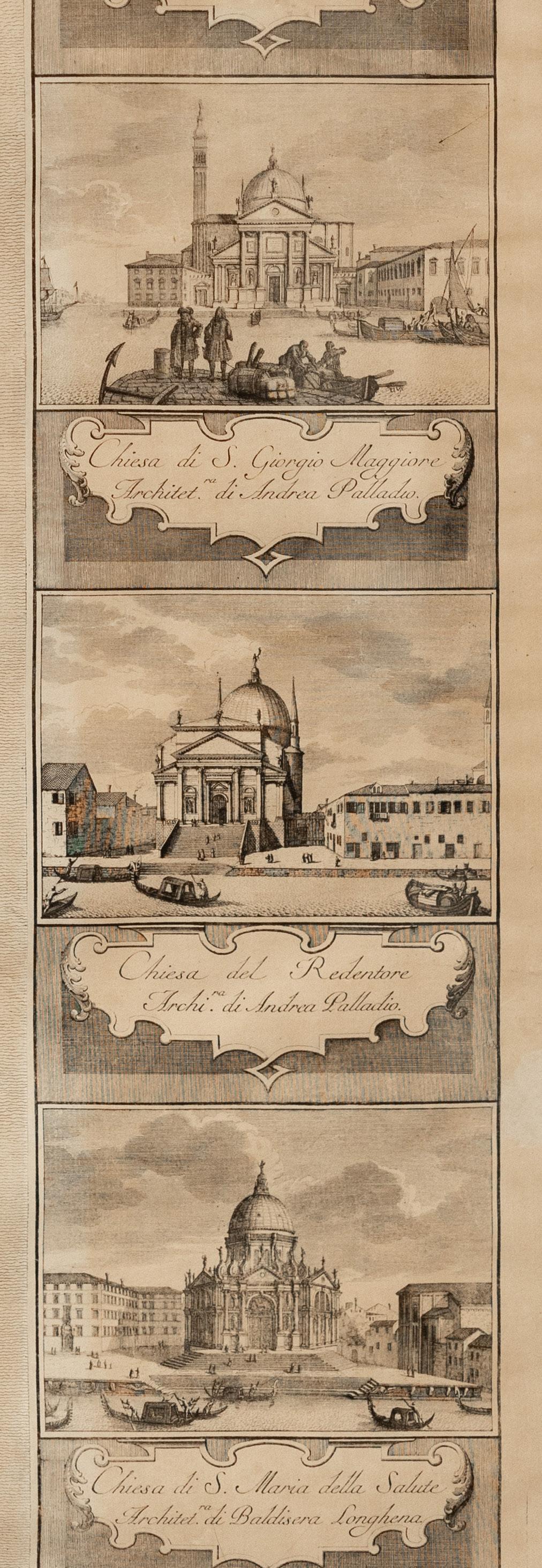

LARGEST OBTAINABLE MAP OF THE FLOATING CITY

Ludovico Ughi (Fl. c. 1700-1740).

[Venice] Iconografica rappresentazione della inclita citta di Venezia consacrata al reggio serenissimo domino veneto.

Engraved map

Venice: 1703 (Second State, 1739)

74” x 83” sheet, 82” x 91” framed

$58,000

Of Lodovico (Ludovico) Ughi, nothing but his authorship — or at least his dedication — of the present map is known. He signs his inscription as a “Kavalier,” i.e., a cavaliere (knight; this is the only rank) of the Ordine di San Marco. Some sources claim that he was from Bologna or from Ferrara.

His map, however, has gained everlasting fame as the epochal and defining depiction of La Serenissima. Depictions of Venice have a long history, but Ughi’s 1729 plan is based on a re-surveying of the city — no easy task in a swamp — and underlaid depictions of the city well into the XIXc.

Composed from 20 sheets, the vast map (nearly 7 feet wide) is flanked by 16 vignettes engraved by Francesco Zucchi after Luca Carlevarijs (1663–1730) and surmounts eight columns of text detailing the principal sites and structures of the city. At the top-right is an allegorical scene (after Sebastiano Ricci) of La Serenissima atop the lion of Saint Mark, borne by dolphins and escorted by putti, tritons and mermaids. At the upper edge, a putto holds a banner on which is a poem of Sannazaro, “Viderat Adriacis Venetam Neptunus in undis/ stare urbem…” (Neptune had seen Venice, a city standing in the Adriatic waves…) published in 1535. At the bottom left are the arms of the Mocenigo family,[1] which supplied seven doges; the doge at the time of the original plate (the only difference between the first state and the present is the alteration of the publisher at lower right, from Giuseppe Baroni to Lodovico Furlanetto) was Alvise III Sebastiano Mocenigo (1662–1732; r. 1722–1732).

The date of the map is based on Moretto, who gives no explanation. Schulz, citing Gallo, asserts that the map’s “plates were acquired by Furlanetto before 1779, when they were listed as part of his stock.” 1739 is certainly a more plausible date.

Moretto, Gino (ed.). Venetia: le immagini della Reppublica. Padova: Papergraf, 2001; 152.

Schulz, Juergen. “The printed plans and panoramic views of Venice (1486-1797)”. No. 117.

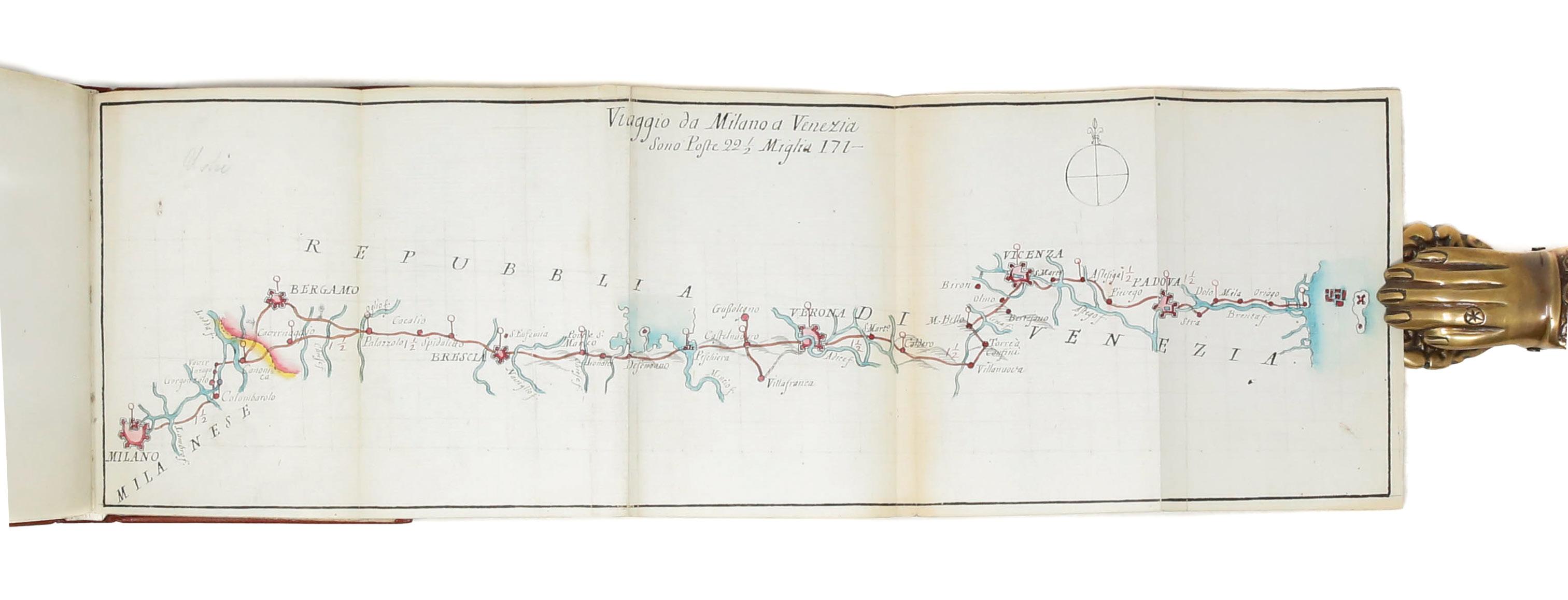

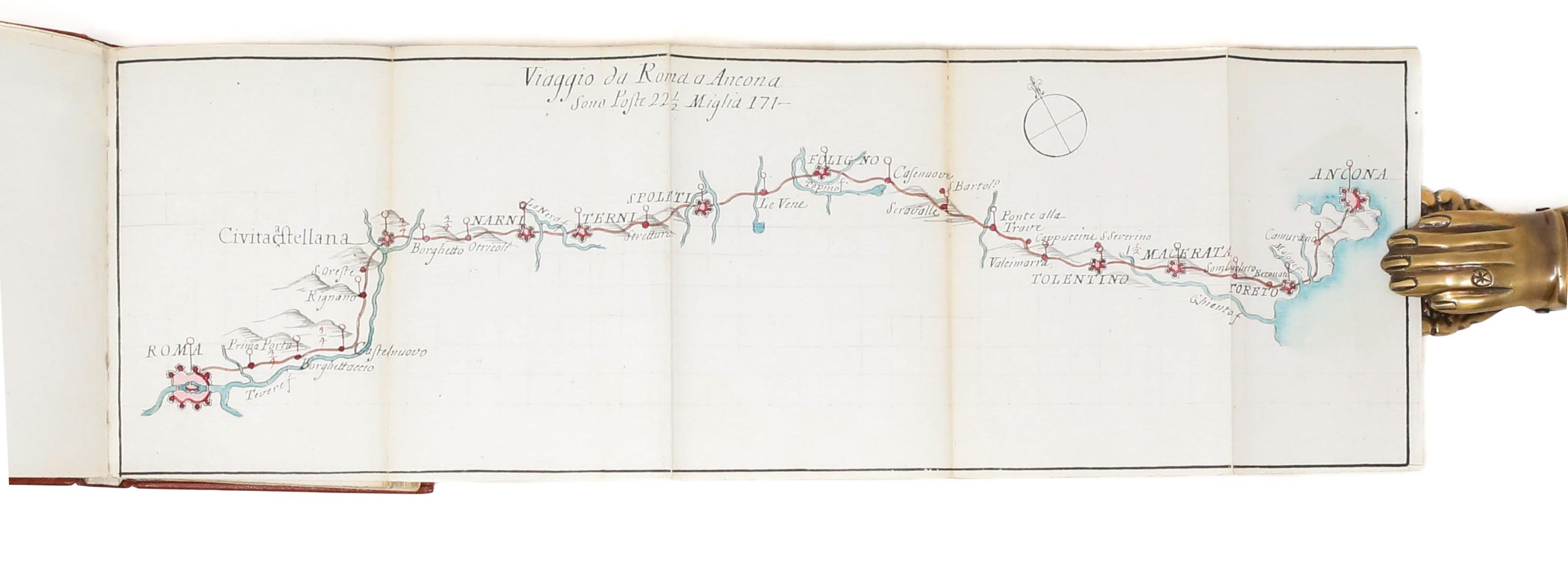

Italian, 18th century

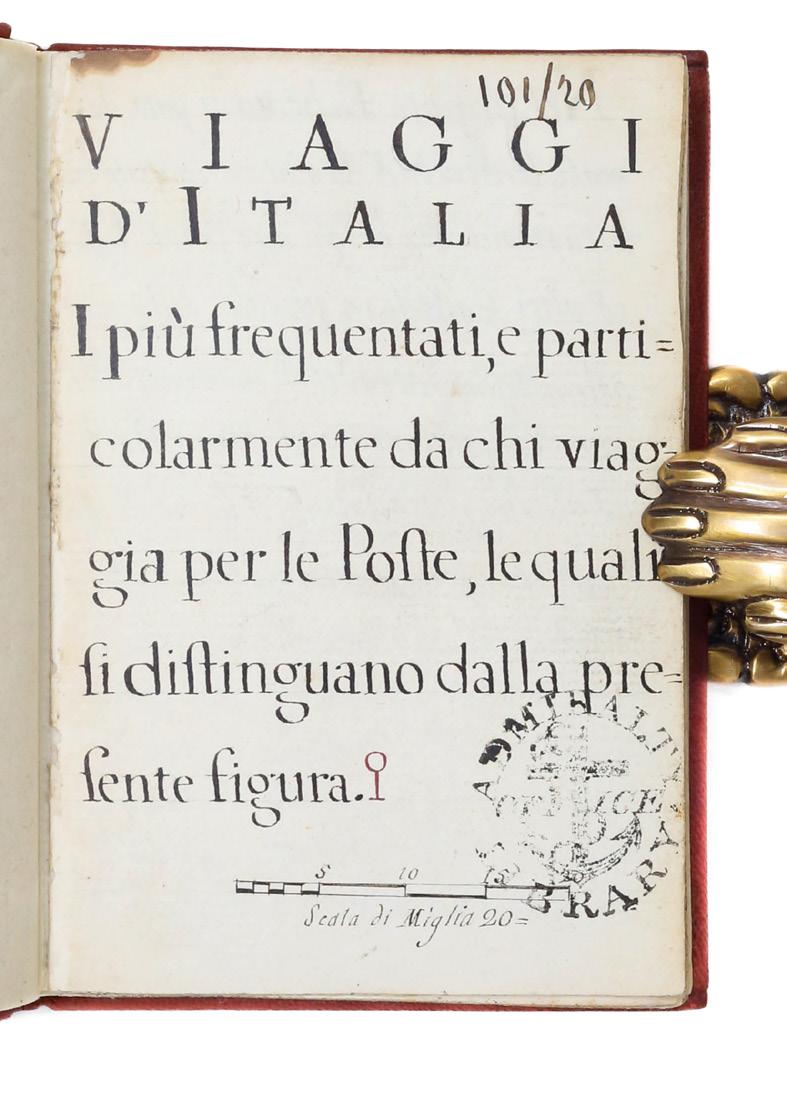

Viaggi d’Italia i più frequentati, e particolarmente da chi viaggia per le Poste, le quali si distinguano dalla presente figura.

[Florence: ca. 1775-1800.]

$9,500

Small octavo in 1s and 2s (5 1/8” x 3 7/16”, 131mm x 87mm): 12 2-311. 32 leaves, pp. iv (title, description, contents, notes) 30 (15 titles on the verso of a leaf, each followed by a folding map of varying length (some made from joined sheets).

With 15 hand-colored manuscript folding maps. Bound in russet morocco in 1968 by “SE” (signed blind on the rear fore turn-in).

As a system of posting or staging — traveling via established routes with designated points for stopping and changing horses — developed in Europe, travelers could move much more quickly and safely than before. Indeed, this is the beginning of the shift from traveler to tourist: the local explorer, keen to see the world but not with any unnecessary discomfort. Small collections of maps such as the present item became part of the necessary equipage of these tourists. Reflecting the most frequent routes of the time (not dissimilar to those taken even now), the maps are for Italy north of Rome, with the exception of the Rome-to-Naples map. The maps are beautifully if simply drawn and colored, but quite precise, with accurate compasses and a consistent scale of about 2mm to the mile. These will have found their way into the hands of wealthy Grand Tourists; this one, perhaps, into the hands of an Englishman.

Although these collections were written and colored by hand, they are not exactly unique; in the libraries of Europe and elsewhere similar volumes exist. The manuscript likely emerged from the workshop of the Giachi family of Florence (cf. Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale Firenze, Fondo Naz. II_XI_4 and II-XI_76; the former is signed by Antonio Giachi). In the closing decades of the XVIIIc they specialized in the production of these little pocket guides, usually with about 15 maps, as here. Errors, such as the erroneous title of map 4 or the misspelling of “medesime” as “mdesime” on line 5 of 11v (p. 2), suggest an exemplar copied by scribes in the workshop.

Lord Wardington (Christopher Pease, 1924–2005; bought at his sale, Sotheby’s London, 9 May 2006, lot 113) was an avid collector of maps and atlases at his home in Oxfordshire, Wardington Manor. A stock-broker by trade, he was a bibliophile by nature: he was the first chair of the Friends of the British Library. In 2004 a fire ravaged the house, and a human chain of villagers bore his books to safety. He was a captain in the Scots Guards stationed in Italy in WWII, and so the present collection must have had no little significance to him. Perhaps he purchased after its deaccession from the Admiralty Office Library, which in addition to records related to the British navy also held material related to travel and exploration.

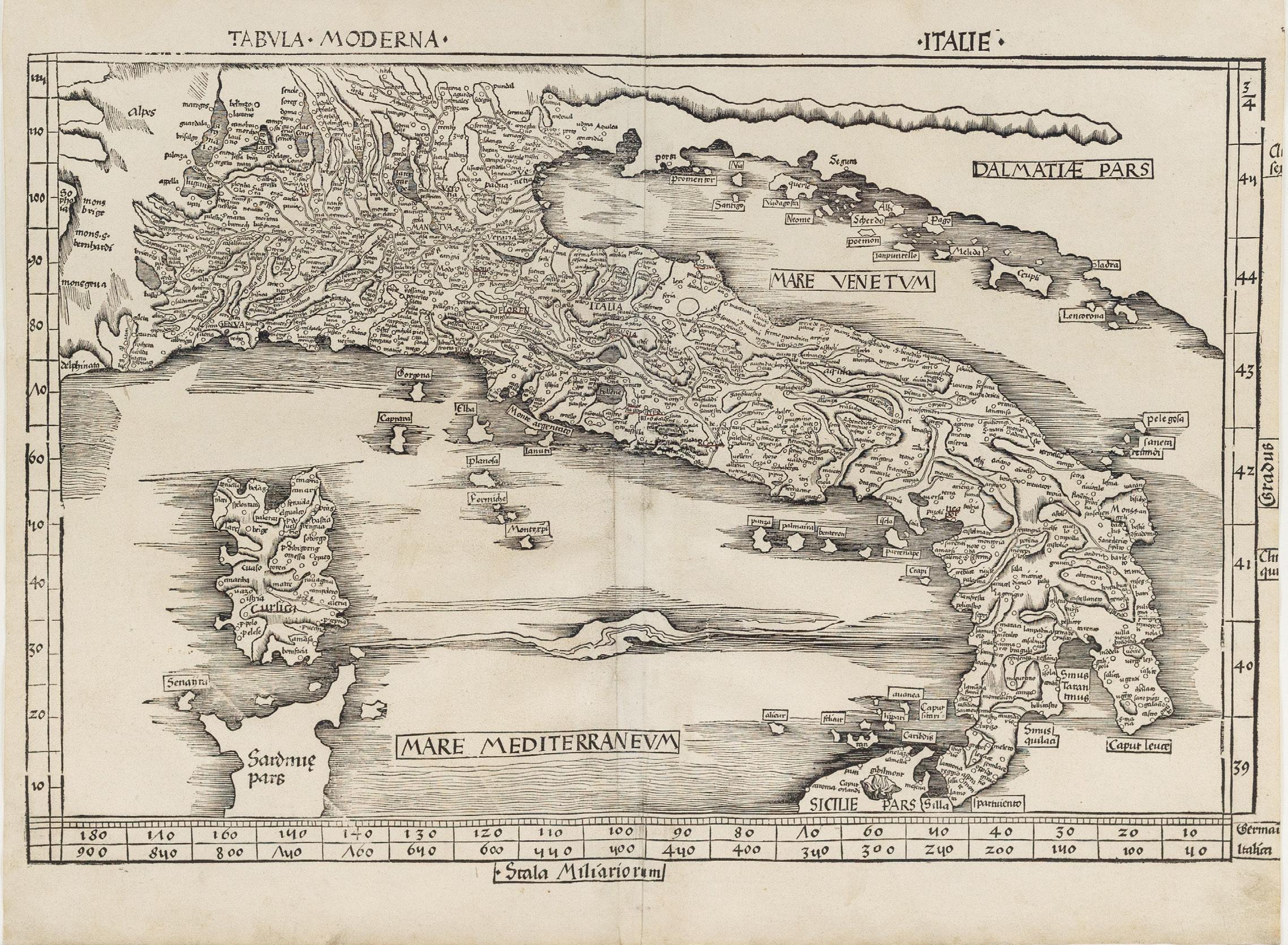

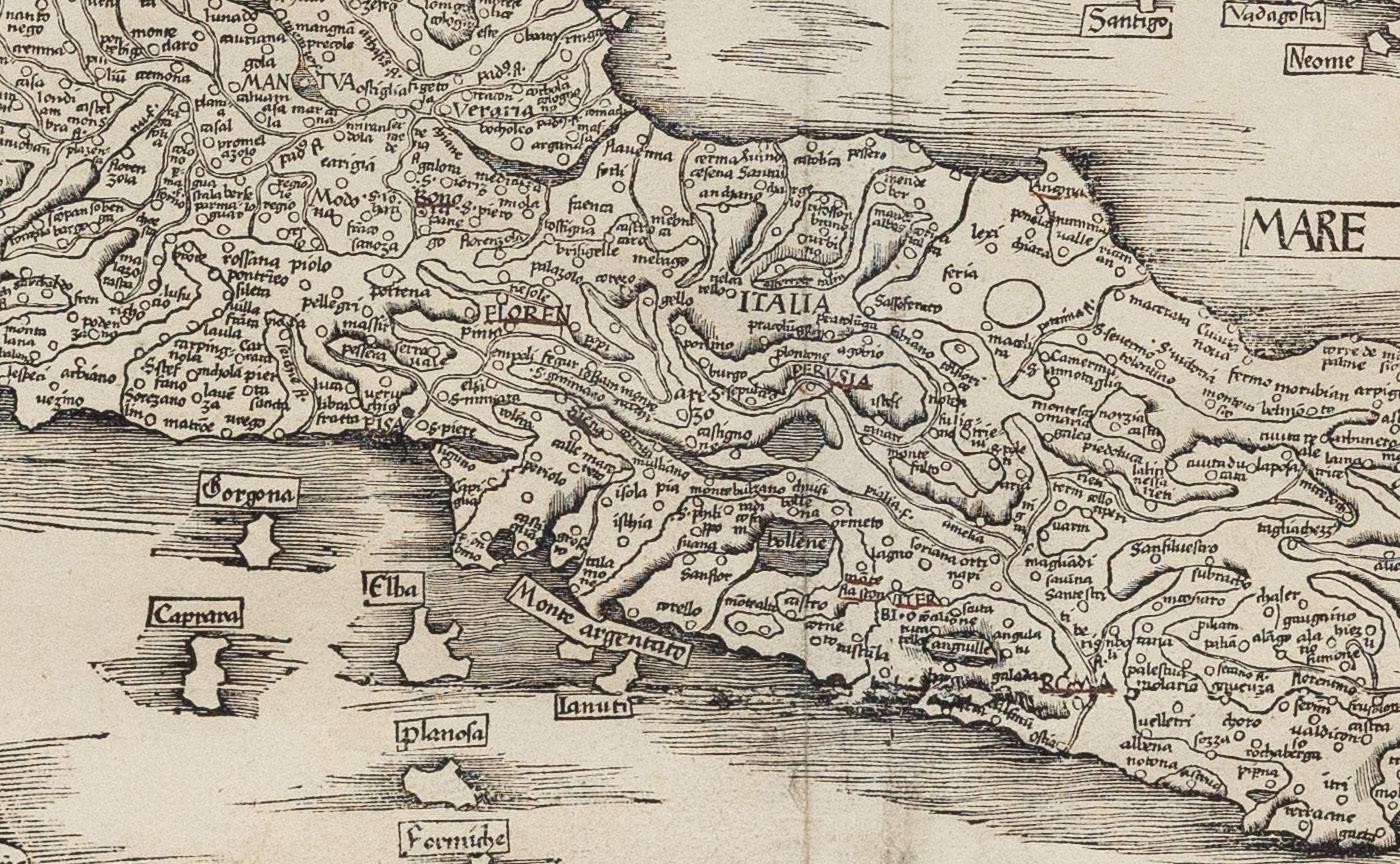

Ptolemy’s First Modern Map of Italy

Martin Waldseemüller (c. 1470-1520)

Tabula Moderna Italie

Woodcut map

Strassbourg: 1513

17 1/2” x 23 1/4” sheet

$9,000

One of the earliest maps of Italy based on modern toponymy rather than classical place names. The present map of Italy is part of the Supplementum Modernior which Nordenskiold calls the first modern atlas of the world. Waldseemüller in the introduction to his Pars Secunda: “We have confined the Geographia of Ptolemy to the first part of the work, in order that its antiquity may remain intact and separate”.

Claudius Ptolemaeus was a second-century philosopher living in Roman Alexandria in Egypt. In the Greek tradition (Ptolemy wrote in Greek, which was the administrative language of the Roman Empire in the Eastern Mediterranean), philosophy — the love of wisdom — bridged what we now divide into the humanities and the sciences; he was a mathematician, natural scientist and geographer-astronomer. No manuscripts of the Geographical Guidance survive from before the 13th century, but some 13th century examples survive with maps that bear some relation to those Ptolemy himself drew. Thus, with the exception of some excavated carved maps, Ptolemy is the source for ancient cartography as well as its culmination.

Florence was the port of entry for the Greek text in Europe (ca. 1400), and almost immediately it was translated into Latin, which was much more widely understood. Various translations circulated, but Ringmann’s is generally regarded as superior to his predecessors’. In the 15th century, the Geographia was the core of ancient knowledge of the world, extending from the Canary Islands in the West to China in the East (though not quite to the Pacific), Scandinavia in the North and beyond the Horn of Africa to the South. It was crucial to explorers; Columbus expected to find the East Indies because of Ptolemy’s calculations and assertions about longitude.

As the world expanded beyond its ancient bounds, discoveries were integrated into the Ptolemaic maps, distinct with their trapezoidal frames. With funding from René II, Duke of Lorraine, Walter Lud, canon in StDié-des-Vosges, gathered a group of humanists to knit together the new knowledge coming from Christopher Columbus and other early explorers with a new translation (Ringmann) and new maps (Waldseemüller). Together they revolutionized cartography, and were likely responsible with the coinage of America and a description of the New World.

Giovanni Francesco Camocio

(Fl. 1550-1575)

Territorio di Roma

Engraved map

Venice: 1559

18 15/16” x 12 13/16” sheet

$4,500

Giovanni Francesco Camocio (active from the 1550’s through the 1570’s) was one of a group of Italian cartographer-booksellers known, a little artificially, as the “Lafreri school.” His name has come to be associated with the present map because it was added in later states, this being the first of Bifolco-Ronca’s four; the point is the absence of an address below the scale. Camocio appears to have cut a near-replica of an anonymous map dated 1557, which is itself based upon a 1556 map attributed to

Vincenzo Luchini, all deriving ultimately from a 1547 map of Eufrosino della Volpaia. These maps all depict Lazio (the territory immediately surrounding Rome) with North at the upper-left corner (i.e., NE at the top). Visible within the city of Rome are the Castel Sant’Angelo, Pantheon and Colosseum.

In the cartouche at bottom left are the impaled arms of the Camera Apostolica (the papal treasury; the crossed keys below the umbraculum in lieu of the papal tiara) and those of the city of Rome (S.P.Q.R., Senatus Populusque Romanus, “Roman Senate and People”). When the Catholic church is sede vacante —between the death of a pope and the election of his successor — the Chamberlain as president of the Camera Apostolica is its temporal leader. Bifolco-Ronca locate this period sede vacante as that between the death of Paul IV 18 August 1559 and the election of Pius IV on Christmas day that year, the longest such period of the XVIc.

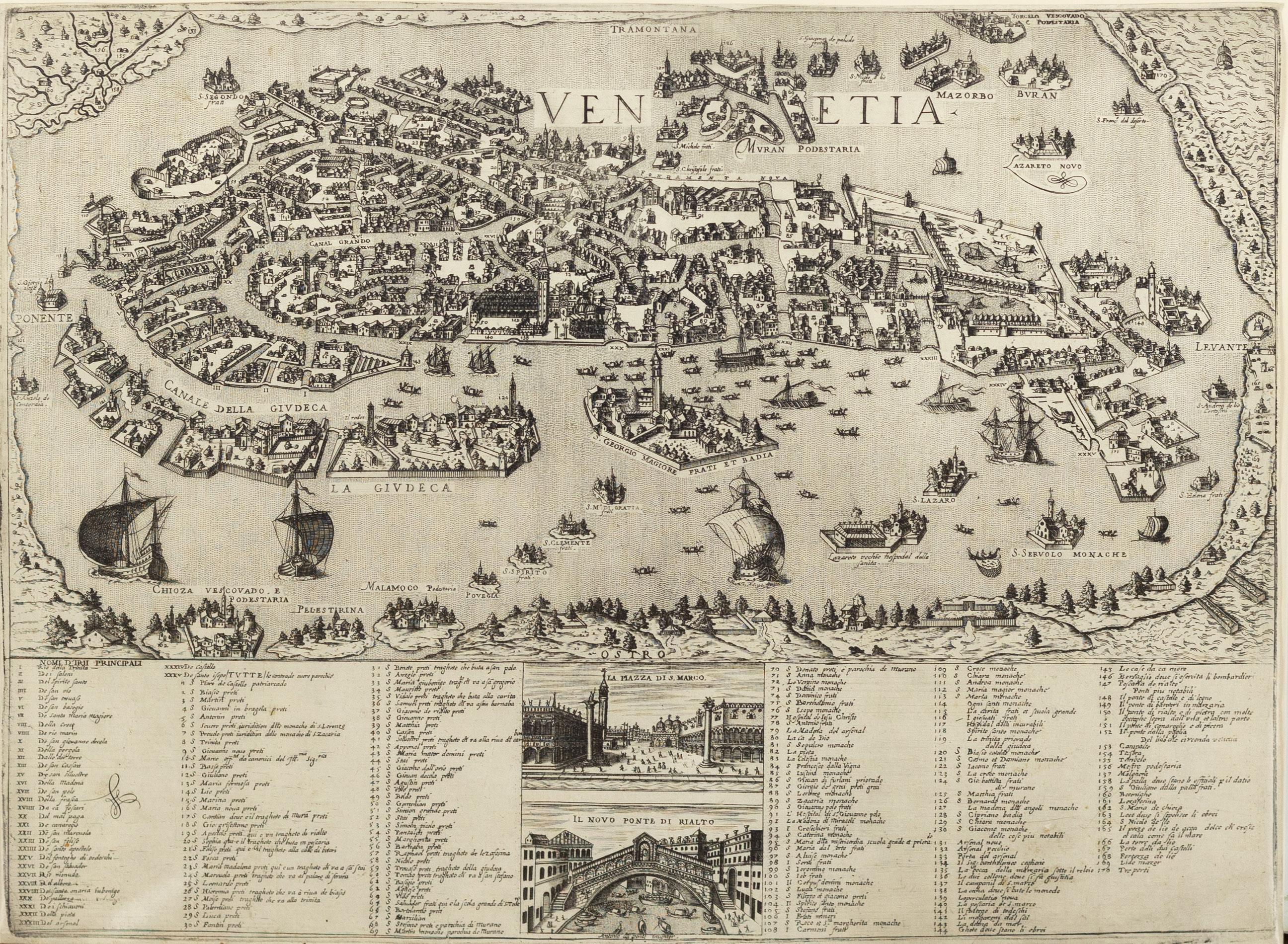

Stefano Scolari (1612-1691)

Venetia

Engraved map

Venice: ca. 1670

20” x 21” sheet

$16,000

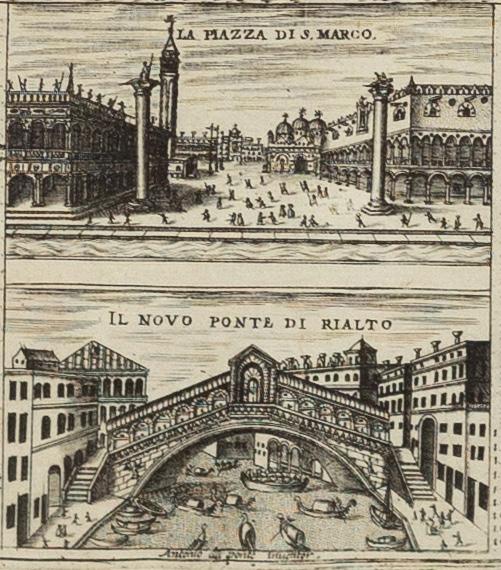

Scarce and highly detailed bird’s-eye view of Venice with extensive index of place names. Set in the center of the index are two englarged views of the famed Piazza San Marco (top) and Rialto Bridge (bottom).

The map is based upon the Bernardo Salvioni (1597) plan of Venice. This gorgeous bird’s-eye view of Venice gives a taste of how this city existed during the seventeenth century. Buildings are shown as well as several traveling vessels including gondolas and ships. Other topographical features are also illustrated.

(1650-1718)

Territorio Bresciano

Engraved map with original hand color in full and elaborate decorative border

Venice: c. 1690

29 1/2” x 18 1/2” sheet

$2,800

Beautifully colored map of Brescia in Northern Italy showing Lakes Garda and D’Iseo.

Vincenzo Maria Coronelli (1650-1718) was a Franciscan friar, cartographer, and publisher based in Venice. Although Coronelli is best known for his globes, some of his noteworthy publications include: Atlante Veneto and Corso Geografico. Coronelli’s international renown led to his employment in various European cities. Most notably, King Louis XIV of France invited Coronelli to Paris and commissioned him to produce a pair of globes, each weighing two tons. Coronelli founded the world’s first geographical society, Accademia Cosmografica degli Argonauti; he was also given the title Cosmographer of the Republic of Venice and Father General of the Franciscan Order.

Coronelli’s thirteen volume cartographic series, Atlante Veneto, was published in Venice between 16901698 intended as a continuation of Johannes Blaeu’s Atlas Major. The encyclopedic publication provides information about cartographers and geographers, with celestial, terrestrial and sea charts, depictions of ships and historical figures.

Vincenzo Maria Coronelli

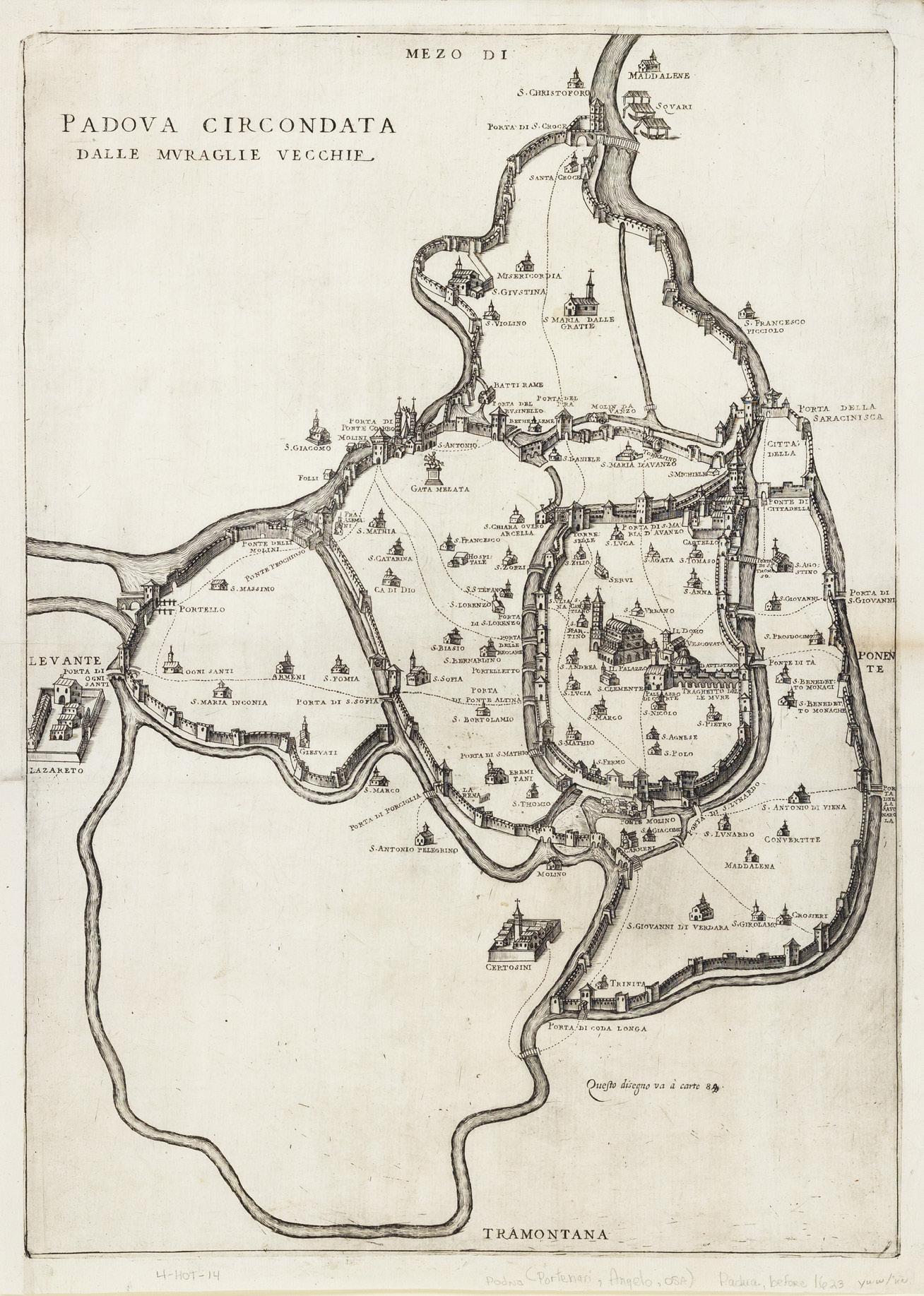

vincenzo Dotto (1572-1629)

Padova circondata dalle muraglie vecchie

Padua: 1623

Engraved map

21” x 15 3/4” sheet

$2,800

RARE & EARLY MAP OF PADUA

This detailed 1623 copperplate engraving by Paduan cartographer Vincenzo Dotto presents a scarce view of the city encircled by its ancient walls. Created during the height of the Venetian Republic’s influence, Dotto’s map reflects the city’s rich architectural and cultural heritage, showcasing its fortified layout, Renaissance buildings, and urban planning before the modernization and expansion of the city. In addition to his maps, Dotto is also known for his architectural work within Padua, including designing the facade of the Church of San Canziano which had previously long been improperly credited to Andrea Palladio.

Two Spectacular views of Rome by the Famed English Artist & Poet edward lear (1812-1888)

edward lear (English, 1812-1888)

The Campagna di Roma taken from Cervara

Signed with monogram (lower left); signed, inscribed and dated ‘The Campagna di Roma taken from... of Cervara,/looking East to the Sabine Hills/Painted from drawings made on the spot in 1859, 1860; and completed by me for/Walter Congreve Esq. in 1871/ Edward Lear/San Remo (on a label on the reverse)

Oil on canvas

25 9/16” x 51” canvas

Provenance:

Commissioned directly from the artist by Walter Congreve Esq., San Remo.

The

Campagna di Roma

Signed with monogram (lower left); further signed, inscribed and dated ‘The Campagna di Roma. Taken from the Quarries of Cerbara, looking/ South-East towards the Volscian Hills & Alban Mount./ Commenced by me from drawings made on the spot in 1859-1860 & completed/for Walter Congreve Esq. in 1871/ Edward Lear./ San Remo/ June 18.1871’ (on a label on the reverse)

Oil on canvas

25 9/16” x 51” canvas

Provenance:

Commissioned directly from the artist by Walter Congreve Esq., San Remo.

$185,000 each or $350,000 for the pair

Edward Lear was born into a middle-class family at Holloway, North London, the penultimate of twenty-one children (and youngest to survive) of Ann Clark Skerrett and Jeremiah Lear. He was brought up by his eldest sister, also named Ann, twenty-one years his senior. Owing to the family’s limited finances, Lear and his sister were required to leave the family home and live together when he was aged four. Ann doted on Edward and continued to act as a mother for him until her death, when he was almost fifty years of age.

Lear was already drawing “for bread and cheese” by the time he was aged sixteen and soon developed into a serious “ornithological draughtsman” employed by the Zoological Society and then from 1832 to 1836 by the Earl of Derby, who kept a private menagerie at his estate, Knowsley Hall. He was the first major bird artist to draw birds from real live birds, instead of skins. Lear’s first publication, published when he was nineteen years old, was Illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots in 1830. One of the greatest ornithological artists of his era, he taught Elizabeth Gould while also contributing to John Gould’s works and was compared favorably with John James Audubon.

In 1842, Lear began a journey into the Italian peninsula, traveling through Lazio, Rome, Abruzzo, Molise, Apulia, Calabria, and Sicily. In personal notes, together with drawings, Lear gathered his impressions on the Italian way of life, folk traditions, and the beauty of the ancient monuments. He eventually settled in San Remo, on his beloved Mediterranean coast, in the 1870s, at a villa he named “Villa Tennyson.”

In 1846, Lear published A Book of Nonsense, a volume of limericks that went through three editions and helped popularize the form and the genre of literary nonsense. In 1871, he published Nonsense Songs, Stories, Botany and Alphabets, which included his most famous nonsense song, “The Owl and the Pussycat,” which he wrote for the children of his patron Edward Stanley, 13th Earl of Derby. Many other works followed.

Lear’s nonsense books were highly popular during his lifetime, but a rumor developed that “Edward Lear” was merely a pseudonym, and the books’ true author was the man to whom Lear had dedicated the works, his patron the Earl of Derby. Promoters of this rumor offered as ev-

idence the facts that both men were named Edward, and that “Lear” is an anagram of “Earl.”

Lear’s nonsense works are distinguished by a facility of verbal invention and a poet’s delight in the sounds of words, both real and imaginary. A stuffed rhinoceros becomes a “diaphanous doorscraper.” A “blue Boss-Woss” plunges into “a perpendicular, spicular, orbicular, quadrangular, circular depth of soft mud.” His heroes are Quangle-Wangles, Pobbles, and Jumblies. One of his most famous verbal inventions, the phrase “runcible spoon,” occurs in the closing lines of The Owl and the Pussycat and is now found in many English dictionaries.

Among other travels, he visited Greece and Egypt during 1848–49, and toured India during 1873–75, including a brief detour to Sri Lanka. While traveling he produced large quantities of colored wash drawings in a distinctive style, which he converted later in his studio into oil and watercolor paintings, as well as prints for his books. His landscape style often shows views with strong sunlight, with intense contrasts of color.

Throughout his life he continued to paint seriously. He had a lifelong ambition to illustrate Tennyson’s poems; near the end of his life a volume with a small number of illustrations was published. After a long decline in his health, Lear died at his villa in 1888 of heart disease, from which he had suffered since at least 1870.

LEAR IN ROME

Edward Lear travelled to Rome for the first time in December 1837, and he spent most of his time in the city until 1848, returning subsequently in the winters of 1859-60, 1871 and 1877. Each summer the artist would spend time exploring other parts of Italy. Lear started painting in oil in 1838. His compositions were mostly created in his studio starting from his travel sketchbooks.

The artist was fascinated by the beauty and force of nature that led him to create the most poetic of views and landscapes. Rome and its surroundings acted as a great source of inspiration for Lear and inspired the creation of his first travel book, Views in Rome and its environs, published in 1841.

The present paintings were painted starting from sketches made by Lear on the spot in the tufa quarries of Cervara, east of Rome, during winter 1859-60. He wrote "there is a charm about this Campagna when it becomes all purple & gold, which it is difficult to tear one’s self from. Thus-climate & beauty of atmosphere regain their hold on the mind-pen & pencil."

Lear’s brushwork reveals his command of the medium. He uses sweeping horizontal strokes to render the distant mountains with myriad lilacs and lavenders, and rich impasto to capture the texture of the rocks bathing in the golden Mediterranean light. Lear also explores the contrast of complementary colors alongside the contrast of light and shadow in the late afternoon. Rather than remaining studies of terrain, the canvases introduce typical Italian countryside figures — paesanos — that would have appealed to Congreve’s post-Grandtour attitude toward the Continent.

the 1822 ERUPTION OF MOUNT VESUVIUS

john thomas serres (1759-1825)

A British Frigate in the Bay of Naples

Oil on canvas

Signed and dated at lower center “Giov.ni T. Serres/ 18

23.”

32” x 42” canvas; 36” x 52” framed

$175,000

The golden age of Naples was epitomized through art, culture, science and modernity reaching an apex. Naples enjoyed a period of rapid modernity, an influx of cultural institutions, and critical industrial developments, such as the implementation of the first railroad in Italy. In 1734, Spanish prince, later known as King Charles III, conquered Naples and Sicily to come under rule of the Spanish Bourbons. In remaining steadfast with the eighteenth century theme of “Enlightened absolutism,” the Spanish autocratic ruler sought to modernize Naples, culturally grow the city, as well as create social and political reforms for the city.

When Charles III took the throne to rule both Naples and Sicily, he immediately commissioned artists to paint his portrait, thus leading to a surge in Neapolitan art. Additionally, there were a number of building projects and the restoration of royal residences that led to a cultural flourishing. The city blossomed artistically, economically, and politically under the Bourbon dynasty, especially through the patronage of Charles III. Commissions under Charles III gave way to the development of Naples and the city’s golden age. The Kingdom of Naples comprised all of Italy south of the Papal States, including Sicily. Moreover, Naples proved to be one of the most powerful and alluring European cities at the latter half of the 1700s throughout the early 1800s.

After the Napoleonic Wars, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was established in 1816 which consisted of a merger between the Kingdom of Naples and the Kingdom of Sicily under King Charles III. Although Charles III had ruled both Sicily and Naples, they were technically still two separate kingdoms until he merged the two in 1816. Following the unification of Sicily and Naples, Naples became the capital. Therefore, the port of Naples was paramount to the continued success of the Bourbon dynasty. The city’s position in the Mediterranean Sea made Naples a hub for trade, commerce and other maritime activity which is clearly referenced in the painting by Serres. The Spanish Bourbons ruled Naples until 1860, roughly ten years before the unification of Italy in 1871.

A British Frigate in the Bay of Naples, created in 1823, is evocative of the growth and prosperity Naples was experiencing up to and throughout the 1800s. Serres’s view shows an English frigate at anchor in the bay, flying the Blue Peter, indicating that she is ‘ready to depart’. The bay is filled with local small craft, one of which is flying the red and white colours of Malta. Behind the frigate, to the left, is Castel dell’Ovo on its promontory, and further to the left Castel Nuovo, a thirteenth century stronghold rebuilt by the Aragonese conquerors of Naples in the mid-fifteenth century. The buildings of the Old City march up towards the star-shaped Castel Sant’Elmo, which crowns the horizon with the dazzling white complex of the Certosa di San Martino. In the distance Vesuvius is seen erupting.

John Thomas Serres was born 1759 in London and was the eldest son to artist Dominic Serres, the Elder. Serres inherited his father’s position as Marine Painter to King George III in 1793 following his passing. Serres’s work is represented in numerous presitigous institiutional collections including the Royal Collection, London and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

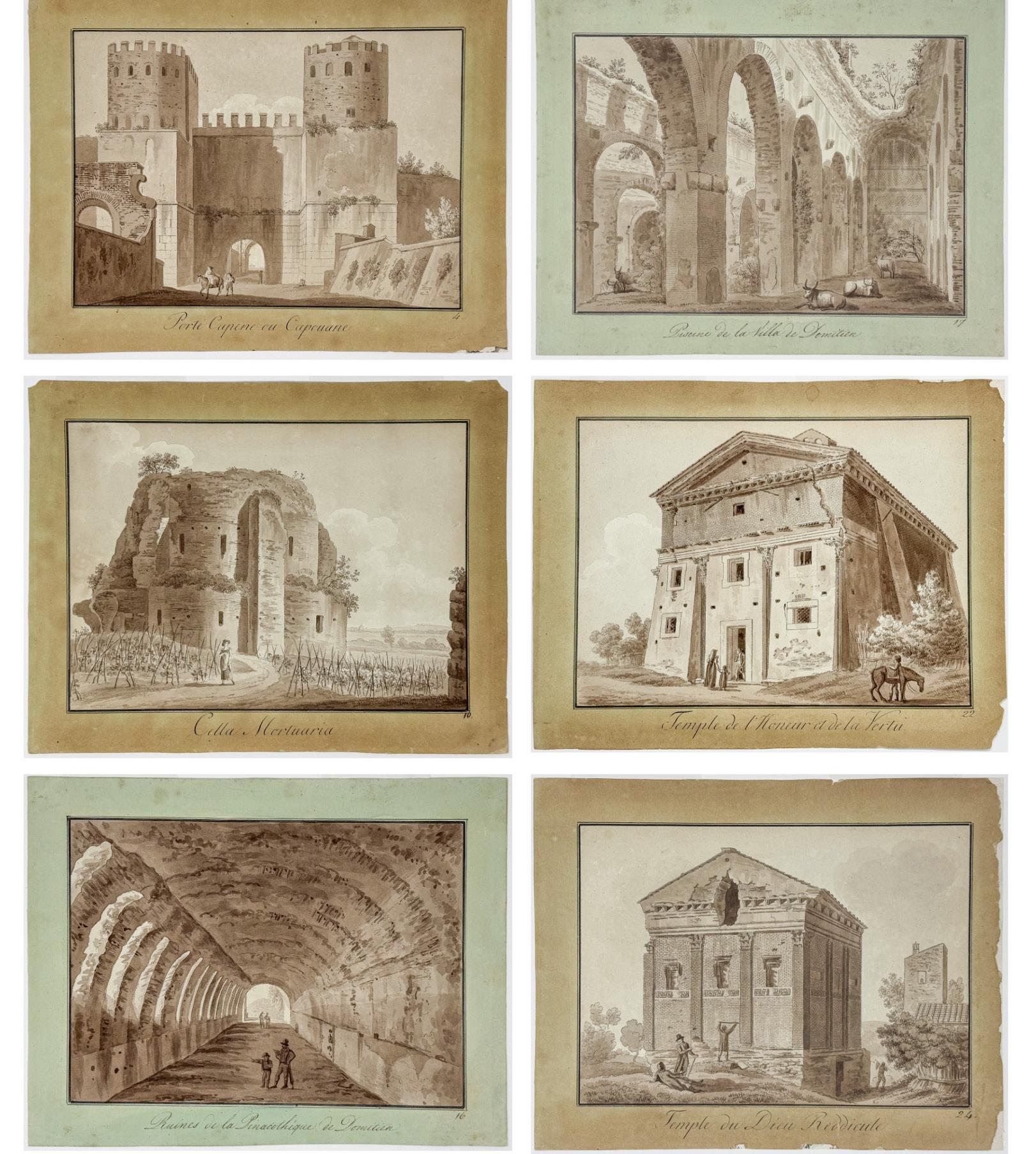

Angelo UGGERI (1754-1837)

Six ink-and-wash paintings over etched lines from his series “Journées pittoresques des édifices antiques dans les environs de Rome”

Rome: A. Fulgoni, 1804[–1810]

Approximately 9 1/2" x 11" each sheet

$4,200 for the set

1) Porte Capene ou Capouane; no. 4, pt. I (1804)

2) Cella Mortuaria; no. 10, pt. I (1804)

3) Ruines de la Pinacothéque de Domitien; no. 16, pt. V (1810)

4) Piscine de la Villa de Domitien; no. 17, pt. V (1810).

5) Temple de l’Honeur et de la Vertù; no. 22, pt. I (1804)

6) Temple du Dieu Reddicule; no. 24, pt. I (1804)

Angelo Uggeri (1754–1837) was an abortive seminarian who was wooed to the ways of architecture and art-history. Working in the generation after Piranesi (whose prints continued to be made and sold by his descendants well into the XIXc), he saw the ruins of Rome and the Italian landscape surge in the imaginations of Grand Tourists and scholars both as pathways to history and as embodiments of the aesthetic category of decay. Uggeri came under the patronage of Angelika Kauffmann, who was a nexus for German-speaking (and other Protestant) visitors to Rome; she provided him with introductions as well as, probably, money for the early volumes of his ambitious Journées pittoresques: a series of described and illustrated journeys out of Rome in particular directions.

Although published from 1804, the Journées began from a series of drawings begun in the late 1780’s and into the 1790’s. The first of five journeys, albeit augmented with supplementary discourses on architectural orders and other more academic studies, was the Journée de Capo di Bove, et vallée des Camenes (published in 1804 with parallel text in Italian), and four of the six present works are from this first itinerary along the Via Appia heading southeast from Rome — now the route to Ciampino airport — into the Alban Hills. The remaining two — both depicting the villa of Emperor Domitian (r. ad 81-96) — are in the same area, viz. along the shores of Lago Albano near Castel Gandolfo. These came from the fifth and final journey, Vues pittoresques d’Albano et de Castel Gandolfo (1810).

The published illustrations are etchings, but entirely linear in style; they are really quite spare, doubtless meant principally to indicate that the tourist had reached the right place. The six present pictures are lavishly ink-washed, such that the etching becomes almost invisible (indeed, previous cataloguers and even contemporary museum descriptions call these inkand-wash drawings). They were presumably produced by Uggeri as de luxe pictures to be hung (as the drawing-pin holes in our plates indicate). Though similar assemblages have come up at auction, these inked etchings are held primarily in a few institutions. In 2015 the Lindenau-Museum in Altenburg had an exhibition from among their 249 Uggeri views, more or less identical to these (although many of theirs without the manuscript title) in execution and format. The catalogue, Souvenir de Rome Ansichten aus Rom und Umgebung von Angelo Uggeri (1754–1837) (edd. Julia M. Nauhaus and Daniel Roberts) has been an essential resource for the above description.

FIRST EDITION OF THE FIRST BOOK OF CITRUS

Giovanni Battista Ferrari (1584-1655)

Hesperides sive de malorum aureorum cultura et usu. Libri Quatuor

Rome: Hermann Scheus, 1646. First edition.

$28,000

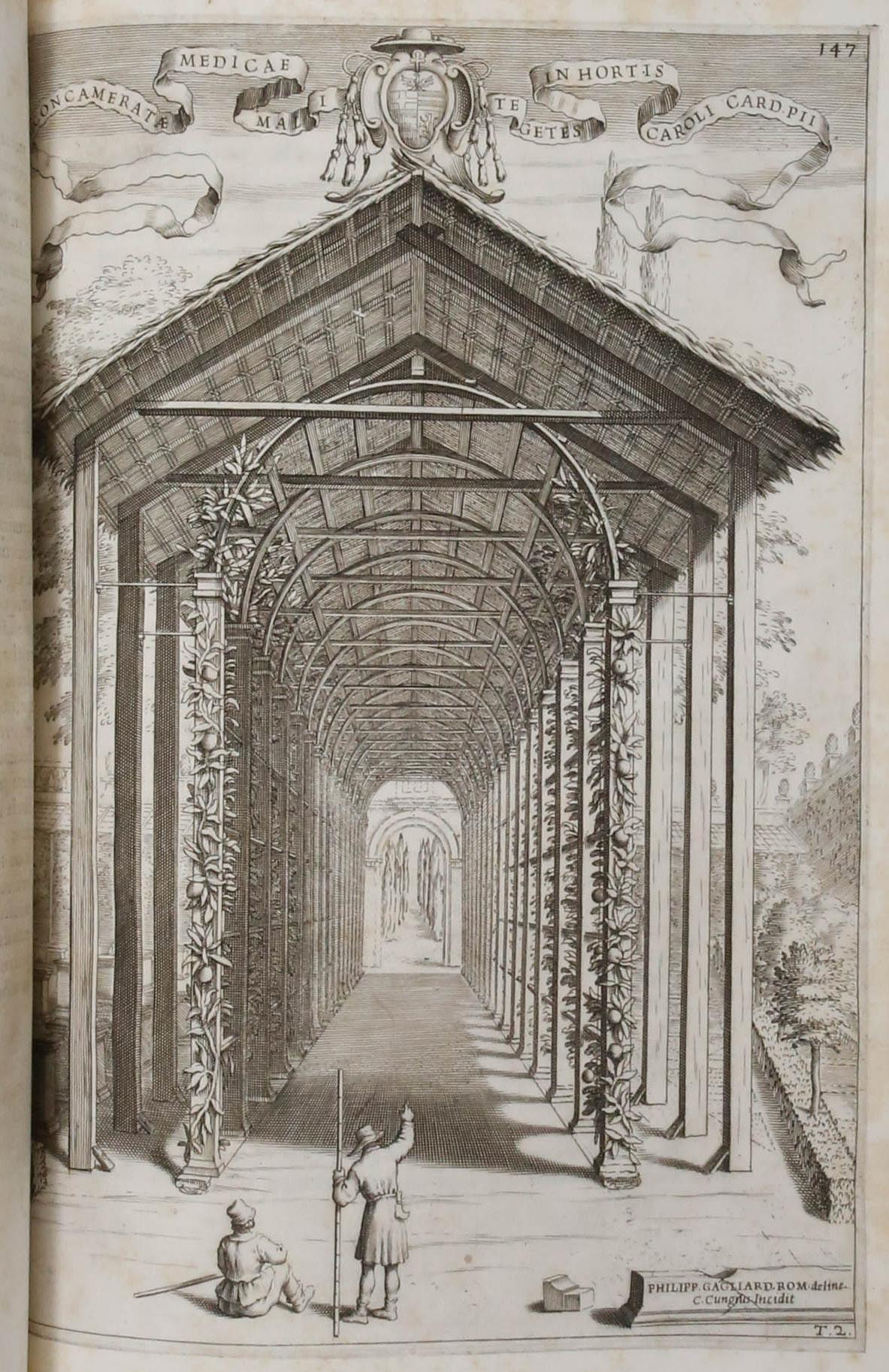

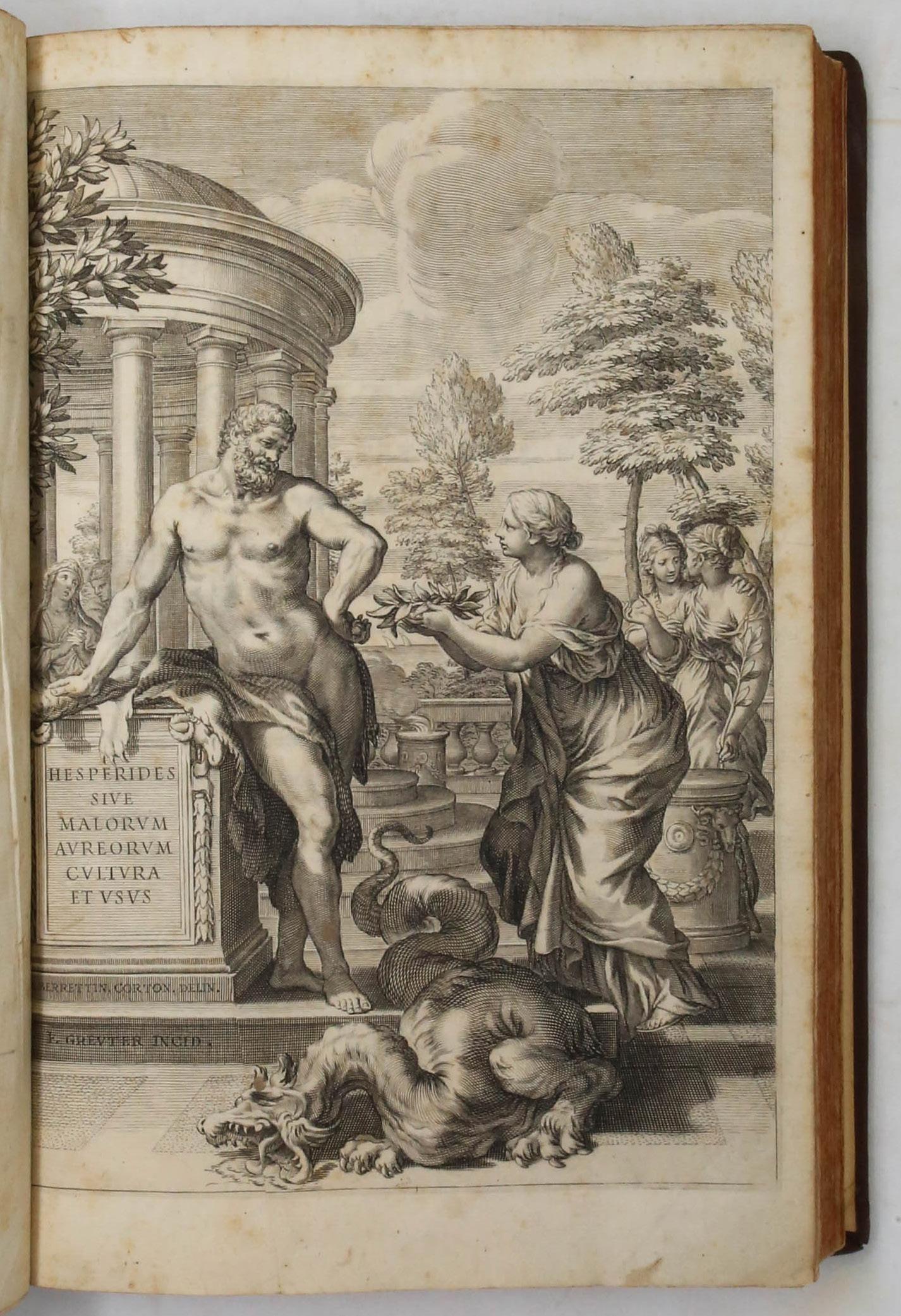

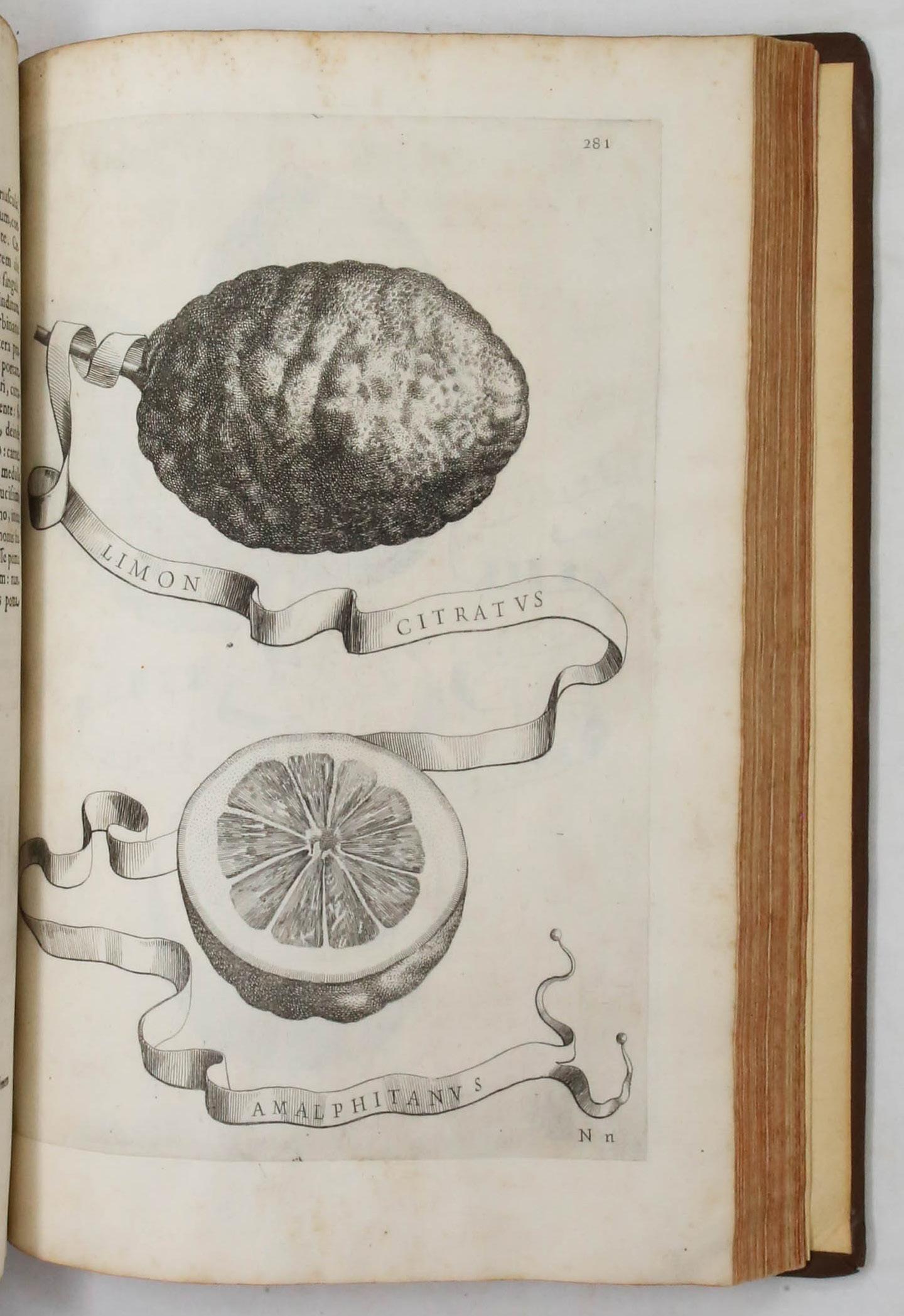

Folio (13 7/8” x 9 3/8”, 352mm x 240mm). Letterpress title, engraved frontispiece by Johann Friedrich Greuter after Pietro da Cortona, 101 engraved plates (of which 80 are of citrus fruits by Cornelis Bloemaert after Vincenzo Leonardi and 8 other non-botanical plates after Andrea Sacchi, Nicolas Poussin, G.F. Romanelli, Domenico Zampieri (Domenichino), Pietro Paolo Ubaldini, Francesco Albani, and François Périer). The remaining plates were engraved by Camillo Cungi, Claude Goyrand and Greuter after Filippo Gagliardi, Guido Reni, and others.

Bound in modern speckled calf, with the original covers laid down. On the spine, six raised bands. Title gilt to red morocco in the second panel, date gilt to red morocco in the fourth panel. (Original) marbled end-papers. All edges of the text-block stained red. Rebound. Internally quite lovely, with mild toning throughout.

One of the most attractive and lavishly illustrated botanical works of the Baroque era. Ferrari’s greatest works were De Florum cultura (1633) and Hesperides (1646). In each he attempted to name and classify new species, his predecessors having failed to provide solid nomenclatural coverage. His second treatise resulted directly from his close association with Cassiano dal Pozzo, one of Rome’s leading scholars and patrons of natural history. Hesperides was a collaborative work, with Cassiano providing the source of much of the information through correspondence and specimens while Ferrari as editor and author dedicated himself to establishing a precise taxonomic classification for this family of fruit.

Hesperides is divided into four books. The first deals with the archaeological, numismatic, mythological, and etymological background of citrus lore, beginning with the story of Hercules’ penultimate labor: his procurement of the golden apples, guarded by the Hesperides, daughters of Atlas. The frontispiece depicts one of the Hesperides timidly offering him the laurel wreath of victory. Three other plates show the arrival of the apples in Italy, specifically at Rome, Lake Garda, and Naples. Also featured are dramatic engravings by Bloemaert depicting the mythological metamorphosis into citrus trees of Harmonillus (after Andrea Sacchi, p. 89), Tirsenia (after Giovanni Francesco. Romanelli, p. 277), and Leonilla (after Domenico Zampieri, p. 419).

The last three books are named after each of the Hesperidean nymphs: Aegle, Arethusa, and Hesperthusa. These are devoted to the citrons, lemons, and oranges over which they presided respectively. Ferrari also details various aspects of the cultivation of citruses that range from propagation, grafting, potting, and pruning to irrigation, manuring, and protection against heat and cold. Several plates depict orangeries and hothouses as well as pruning and grafting tools. Also mentioned in the treatise are culinary uses of citrus such as details on candied peel and pastilles, and recipes for lemon sherbet.

Arader possesses five magnificent 17th century Italian watercolors of citrus fruits, of which three were produced by Leonardi (one corresponding to plate 67 and another very similar to plate 311). Two other drawings of clusters of citrus fruit on branches are attributed by scholar David Freedberg to a 17th century Italian artist whose style parallels that of Leonardi. For information on the watercolors, please inquire. Property from the Estate of Anita Peek Gilger, M.D. (sale, Christie’s New York, 14 October 2003, lot 48); Acquired from: Lathrop C. Harper (1966).

Cleveland Collections 206; Freedberg, David, and Enrico Baldi, The Paper Museum of Cassiano dal Pozzo. Part One. Citrus Fruit, pp. 60-76 passim; Hunt 243; Nissen BBI 621; Oak Spring Pomona 67; Pritzel 2878. See also, Mazzoni, Christina. Golden Fruit: A Cultural History of Oranges in Italy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018).