6 minute read

AQUACULTURE ECONOMICS, MANAGEMENT, AND MARKETING

By: Ph.D. Carole R. Engle*

The startup years are particularly challenging for aquaculture and aquaponics businesses. A great deal of capital is typically required to construct facilities, purchase equipment, acquire seedstock, and to raise the first crop. The startup period may last several years during which adequate capital must be available to cover all expenses and to perhaps support a family. Given that the major reason for business failure is that the owners simply run out of cash, careful and thorough planning is needed to prepare to survive the startup years. This column will discuss several key considerations from the perspective of financial requirements but also that of gaining the management experience necessary to be successful in an aquaculture or an aquaponics business.

Development of an aquaculture or aquaponics business begins with construction of the production facility and acquisition of the necessary equipment. Some individuals use their own cash reserves to cover these initial investment costs, while others rely primarily on borrowed capital from financial lenders or investors. There are costs for the use of either owner equity capital or borrowed (debt) capital. Debt capital results in interest costs that must be paid to the lender in periodic installments. Clearly the greater the amount of capital that is borrowed, the greater the interest cost to the business. If the capital used to build facilities and purchase equipment is from the owner, there is an opportunity cost in the form of the returns that could have been received by investing that capital in a different way or of its value as a reserve for emergencies. The operating costs associated with purchase of the seed, feed, water amendments, utilities, and hired employees must also be paid with either cash reserves from the owner or an operating loan. The most immediate problem for a startup business is the lack of revenue during the startup years. It takes time, often more than anticipated, to get an aquaculture or aquaponics business up and running. For those new to aquaculture and aquaponics, it is advisable to start slowly and not attempt to gear up too quickly to full production levels, to avoid substantial mortalities that often occur due to lack of experience with the animals being raised. The learning curve in aquaculture or aquaponics is quite steep, and it is advisable to invest the time and money to first gain experience on a trial basis with a small unit stocked at a low rate. It may take several crops before the owner is able to tell at a glance whether the animals are doing well or if there is a problem that needs prompt attention.

Another reason to start slowly is that it takes time to build markets,

even with well-known and preferred species. There are not many new businesses that have people immediately clamoring for their product. Unlike more mainstream types of agriculture, there is no grain elevator or auction barn where product can be dropped off. Aquaculture and aquaponics farmers must devote time to develop their own markets by searching out prospective buyers, providing samples, conducting active promotional campaigns, and otherwise convincing individuals to purchase their product.

Starting on a small, trial scale, however, also means that costs will be greater due to the economies of scale that exist in aquaculture and aquaponics. Thus, not only are cash flow problems more pronounced during the startup years, but overall costs are higher and profitability lower or nonexistent.

The startup budgets must reflect the realities of higher costs and cash flow deficits. Detailed plans (including planning for contingencies and

Table 1

Annual revenue projected for first three years of hypothetical, Indoor shrip farm producing 15,000 lb a year at full production. Year 0 1 2 3 Total revenue for year $0 $73,854 $147,708 $221,562

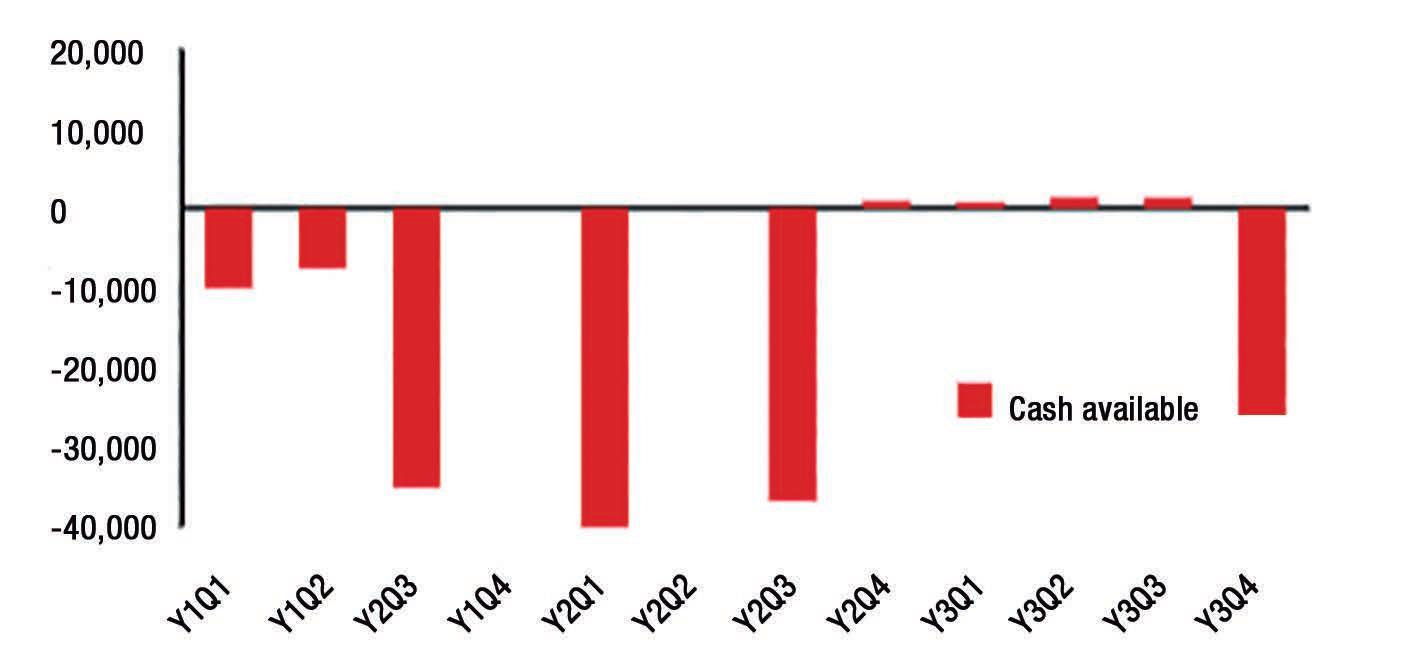

un-anticipated emergencies) must be made to acquire and manage levels of capital that are adequate to survive the early years. Table 1 and Figure 1 illustrate the financial challenges of a hypothetical, startup indoor RAS shrimp farm. (For more detailed financial statements for this hypothetical example request further info to the author). Year 0 of the business was the construction year. The farm was assumed to produce and sell at a level equivalent to one-third and twothirds of full production in Years 1 and 2, respectively (Table 1). Only in Year 3 did the farm reach full production with the expectation to receive full revenue.

The financial problems created by the startup realities are evident in Figure 1, that shows a 3- year cash flow budget (quarterly) for this hypothetical farm. The cash available does not become positive until Year 2, in the second quarter (Y2Q2), but is only marginally positive and remains so for three quarters until becoming substantially negative again in Quarter 4 of Year 3, when annual payments on real estate and equipment loans are due. (This example assumed that the owner contributed 20% of the real estate and equipment investment capital.)

Thorough and accurate planning will minimize the chances of failure, even with the substantial financial risk of the startup years. Unfortunately, many enterprise budgets do not adequately reflect the realities of the startup years. Most published enterprise budgets reflect a steady-state business that has survived the startup years, moved up the learning curve, and is in full production with full sales.

Figure 1

Cash available, first three years of indoor shrimp farm (Y1Q1 = Year 1, Quarter 1)

The above considerations are, of course, in addition to the many decisions that must be made in terms of system construction and design, and accurate and realistic projections of steady-state production volumes, costs, and sales targets. For Additional Resources that provide additional detail on business planning and preparation of necessary financial statements and analyses, please contact the author and request the information.

Another reason to start slowly is that it takes time to build markets, even with well-known and preferred species. There are not many new businesses that have people immediately clamoring for their product.

Thus, a thorough and accurate business plan will include, in addition to the analyses of the business when in full production, financial projections for each year of the entire startup period.

The projections for the startup period should reflect the following: 1) first and second year sales much lower than those estimated at full production; 2) higher costs due to lower scale of production; and 3) contingency cash reserves to work through the many un-anticipated problems that will emerge. Such analyses will clarify the cash flow and borrowing needs for the business and provide a solid basis from which to acquire sufficient capital and better position the farm to survive the critical startup years.

Additional Resources available under direct request to the author. Ph.D. Carole R. Engle*, Engle-Stone Aquatic$ LLC Carole Engle holds a B.A. degree in Biology/Rural Development from Friends World College and M.S. and Ph.D. degrees from Auburn University where she specialized in aquaculture economics. Dr. Engle is a past-President of the U.S. Aquaculture Society and the International Association of Aquaculture Economics and Management. She is currently a Principal in Engle-Stone Aquatic$ LLC, and can be reached at cengle8523@gmail.com