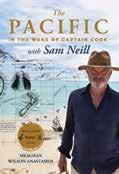

World-first circumnavigation

Around New Guinea by traditional canoe

Barrier Reef mystery wreck

On the trail of the Jardine Treasure

Maritime robots

The future of maritime technology

World-first circumnavigation

Around New Guinea by traditional canoe

Barrier Reef mystery wreck

On the trail of the Jardine Treasure

Maritime robots

The future of maritime technology

ONE OF MY FONDEST MEMORIES leading into the London Olympic Games was working on the design of a vast new gallery for the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich. The Sammy Ofer Wing was to be built right up against the boundary of Greenwich Park. Working with the architects CF Moeller, we had to find clever ways to seamlessly integrate this massive modern structure into a historic World Heritage listed royal park. One way was by creating a series of water features, rills and fountains all carefully positioned around the entrance. Although mainly ornamental, these quickly became one of the most used wetplay interactives in Greenwich Park. Now if you visit Greenwich in summer, you see them ‘adapted’ by families to float paper boats, launch pooh-sticks or simply splash about in. At the time this playful adaptation was largely a happy accident, but for me it’s a powerful reminder of the playfulness and creativity museums can inspire not just in children, but also in adults.

Since the early 1980s museums have developed particular expertise in designing play-centred environments that stimulate children’s imagination, creativity and dexterity. This year the Australian National Maritime Museum launched a new play centre, the Aquatic Imaginarium. The development, led by Annalice Creighton, the museum’s Education and Programs Coordinator, incorporated a range of play-centred activities for children up to 12 years and their families. What Annalice and her team created was an entire learning environment, weaving together a diatom disco sensory space and whimsical sculptures of marine animals, together with a series of carefully conceived and open-ended play activities. The Aquatic Imaginarium has been so successful that we are expanding the concept and bringing it back to Darling Harbour later this year.

But it’s not just children who enjoy playing in museums. This is borne out by responses to our recent visitor survey. When asked their main reason for visiting the Maritime Museum, over half of our adult respondents replied that it was to climb aboard HMAS Vampire, HMAS Onslow and our replica HMB Endeavour. These three ships are enormous interactive environments about which adults as well as children learn primarily through physical interactions – climbing up and down ladders, clambering through hatches, lying in bunks and hoisting sails. I contend that not only are these three ships the largest objects in our nation’s cultural collections, but they are also the most popular playgrounds for adults in Sydney!

Children examine and touch specimens and artefacts in the Aquatic Imaginarium over the summer holidays. Image James Horan Photography

For more than 20 years I have developed play-centred galleries and learning environments at the Australian National Maritime Museum, Powerhouse Museum and Royal Museums Greenwich. In doing so, I have been guided by the work of the education psychologist Howard Gardner who, in his 1983 Frames of Mind study, put forward a list of multiple intelligences as a challenging alternative to rigid, traditional IQ tests. He proposed that humans possess eight distinct units of mental functioning. He labelled these units ‘intelligences’ and asserted that each has its own observable and measurable set of abilities. It was never Gardner’s intention to equate intelligence with play, but I believe he has given museums a wonderful design checklist. Today I continue to use this checklist whenever I approach the task of building a gallery, playground or education centre and always strive to ensure that it incorporates one or more experiences inspired by Gardner’s verbal, inter-personal, intrapersonal, logical, spatial, musical and bodily–kinaesthetic intelligences.

If, like me, you are passionate about play-centred learning in museums, can I recommend the MuseumNext conference. MuseumNext is a major conference series that explores the future of museums and takes place in Europe, North America and now Australia. On 1 and 2 April 2019, the conference is being held here at the Australian National Maritime Museum (see article on page 77) and will feature speakers from around the world discussing the future of play and creativity in our museums.

Kevin Sumption psm Director and CEO Australian National MaritimeMuseum

Acknowledgment of country

The Australian National Maritime Museum acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora nation as the traditional custodians of the bamal (earth) and badu (waters) on which we work.

We also acknowledge all traditional custodians of the land and waters throughout Australia and pay our respects to them and their cultures, and to elders past and present.

The words bamal and badu are spoken in the Sydney region’s Eora language. Supplied courtesy of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council.

Cultural warning

People of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent should be aware that Signals may contain names, images, video, voices, objects and works of people who are deceased. Signals may also contain links to sites that may use content of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people now deceased.

Cover Downward Force on Upward Moving Objects (detail), Wang Luyan, 2018 – one of the works that features in our current exhibition On Sharks & Humanity. Image Samuel Carslake

Number 126

to May

2 A maritime Mordor

The first circumnavigation of New Guinea by traditional sailing canoe

10 $7,000 maritime history prizes

Nominations now open for biennial book and community history prizes

12 Towards 2020 and beyond Cook

Three events coincide to prompt debates about our national identity

18 Black reefs and the ‘Jardine Treasure’

The Boot Reef Project and a mystery shipwreck

26 Remembering AE1’s lone New Zealander

The short life of Able Seaman John ‘Rosy’ Reardon

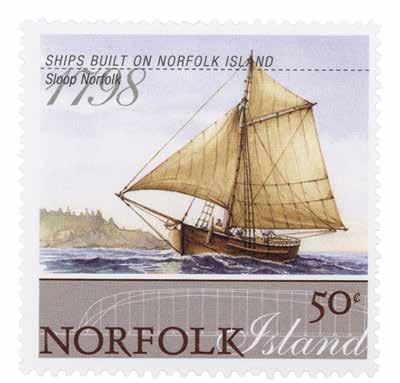

30 The colonial sloop Norfolk

A question of tonnage – did Matthew Flinders get it wrong?

36 The rising tide of maritime robots

Autonomous vehicles revolutionise maritime industries and research

38 The Seabin Project

An Australian innovation helps to clean up our oceans

40 Ida – for love of a classic yacht

A century-old yacht: restored, researched and returned to its birthplace

46 Reconciliation in action

Respecting and involving Indigenous communities in everything we do

48 The Australian Maritime Museums Council

Connecting, discussing and sharing maritime heritage

52 Message to Members and museum events for autumn

Your calendar of activities, talks, tours and excursions afloat

58 Member profile

Welcoming Dawn Gardiner to our new Captain’s Circle

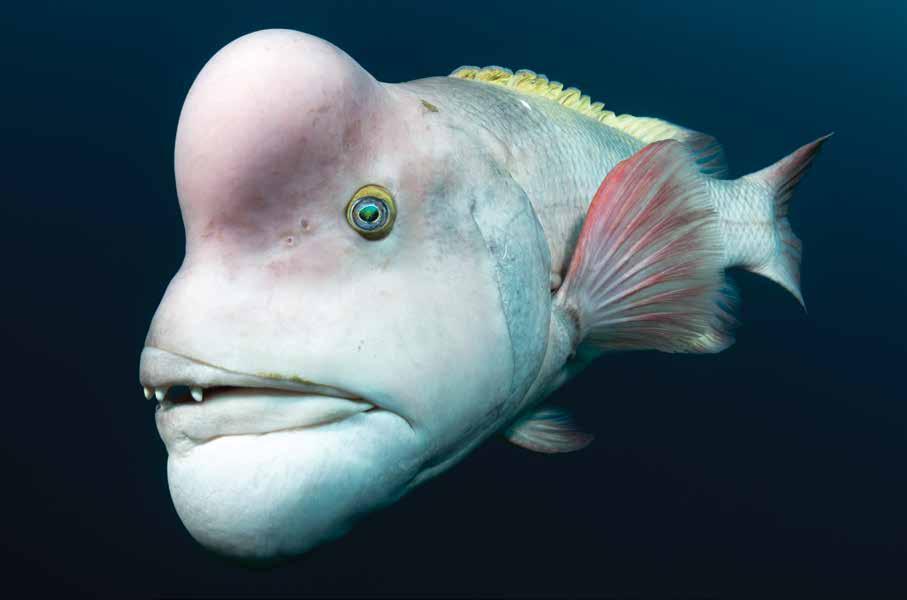

60 Autumn exhibitions

Wildlife Photographer of the Year ; The daring ship: HMAS Voyager and more

64 Foundation

Telling the stories of a nation of migrants

66 Collections

A tea tray memorialises the death of Captain Cook

70 Welcome Wall

A teenage Italian proxy bride finds a new life in Australia

74 Readings

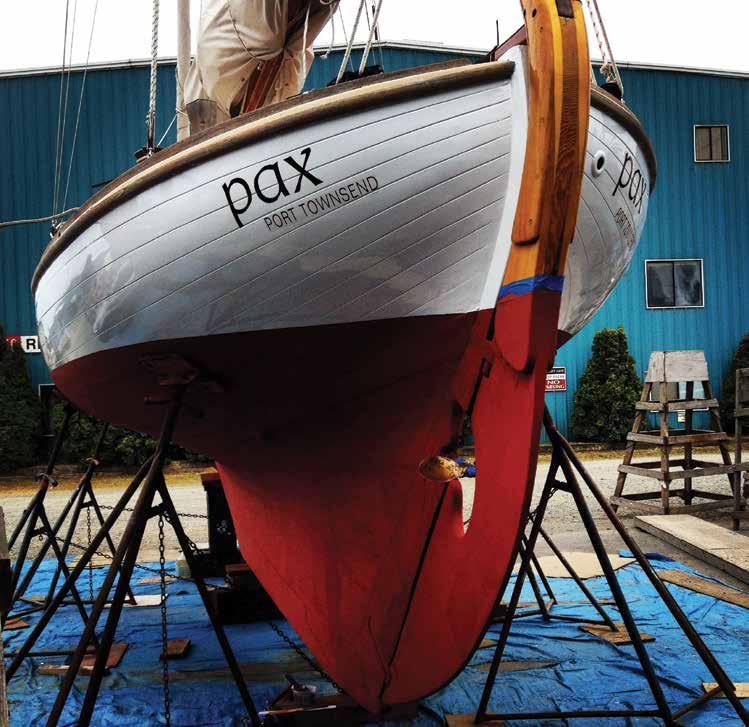

Finding Pax by Kaci Cronkhite

76 Currents

New honourees to the Australian Sailing Hall of Fame; MuseumNext conference

It was intense sailing and several surprise waves just appeared out of nowhere and crashed over our outrigger

Waves in the Gulf of Papua about to break over the outrigger. All images © Thor F Jensen

On 30 August 2016, Danish filmmaker Thor F Jensen and three Papua New Guinean master sailors embarked on the world’s first circumnavigation of the island of New Guinea in a traditional sailing canoe. Their modern-day odyssey covered 6,300 kilometres, took almost 14 months, and faced relentless monsoon winds, dangerous seas, pirates and crocodiles. This is an edited excerpt from Thor F Jensen’s forthcoming book and film of the journey, Salt Water and Spear Tips.

Trying to navigate those breakers in the dimming light at this time of year would be virtual suicide

01

Justin John steering with the yabby yabby (rudder) and Sanakoli John working the mansiti (mainsheet).

02

When the crew first called into Apiope the villagers hid themselves in their huts, but soon the sailors were welcomed.

We were about to sail the most dangerous stretch of coast in the entire Gulf of Papua

THE GULF OF PAPUA WAS A FRIGHTFUL SIGHT, and even more daunting was that people actually ran small dinghies through this maritime Mordor of two-metre-high brown, barrelling destruction. Now I was on one of those vulnerable fibreglass craft, speeding between long rows of breakers. The dinghy driver would see the forming pattern ahead and steer out of one churning boil after another. Every time we made a last-minute escape, he would widen his eyes and exclaim, ‘Zazazazahhhh! ’ There was no doubt that we had a skilled captain and that he was in that perfect ‘sweet spot’, where your skills are challenged to the extreme but you prevail – although I didn’t know how long this would last, because he and his mates were hitting the ‘jungle juice’ (home brew) pretty hard.

When I arrived in the village of Apiope with a bag of sparse provisions, I was greeted by my crew, Milne Bay master sailors Sanakoli and Justin John. Together with the brothers, I was attempting a great world record: the first circumnavigation of the island of New Guinea in a traditional sailing canoe –a 6,300-kilometre odyssey that began on 30 August 2016 from the Tawali Resort in Milne Bay Province. I was worried how they were feeling about taking our chances in the Gulf, so I was glad that I could at least deliver a positive weather report promising fair winds and lower waves for the next couple of days. My companions were used to navigating through their home islands by sight and what I can best describe as instinct. During our last 12 months of coastal travel, we had combined their sense of the sea with charts, a compass and a GPS. I unfolded the map and pointed to the route ahead: ‘There are some difficult sections by the river mouths.’ Sanakoli replied, ‘We take the route, easy-easy, first Vailala, next day we look for the weather, if good we go to K-town [Kerema].’

Early the following morning, we tied everything down on the canoe. Our vessel, named Tawali Pasana (meaning ‘reef flower’ in the Tawal language) was basically a nine-metre-long dug-out tree trunk with a 20-centimetre strake on each side, supported by a long outrigger pontoon in lightwood. The sailau, as this type of canoe is called in Milne Bay, had been built four years previously on Basilaki Island off the eastern tip of mainland Papua New Guinea and used for shark fishing and transport. It was a traditional design with some modern materials. The sail was sewn of plastic sheets, copper nails were used in the strake and the lashings on the outrigger were tied with 50-pound fishing line.

A curious nod to history was the sealant between the strake and the hull. Instead of the traditional glue boiled from bark, our canoe was puttied with tar boiled from a World War II oil drum that Justin and Sanakoli’s father had salvaged from the bottom of the sea. Finally, our bow had a feature inspired by the outer islands – a board covering the top of the bow to avoid swamping when digging into waves. This combination of traditional and outside influences made Tawali Pasana an apt metaphor of contemporary New Guinea. The wind and sea looked promising, but we were vigilant all the same – we were about to sail the most dangerous stretch of coast in the entire Gulf of Papua.

The first difficulty was to get out from the beach. Then, we had to sail east passing the two conjoining river mouths by Apiope (where a dinghy had capsized two weeks prior to our arrival). Unlike a dinghy, Tawali Pasana couldn’t turn on a plate; we had to use the wind and yaya-towa (meaning ‘come about’) every time we needed to change direction. The sailors would have to calculate our course with reference to the lines of breaking swell ahead and thus avoid dangerous sections of canoefloundering waves. If anyone could pull this off it would be Justin and Sanakoli John. Soon one geyser after another exploded off our bow. Tawali Pasana resolutely dug through the growing breakers.

The sheet was tightened then slackened by Sanakoli as Justin stood with stoic alertness by the yabby-yabby (a wide-bladed paddle used as rudder) and cautiously navigated us out through the maze of deceiving conditions. I was fully occupied emptying our ever-filling hull with our bailer (a helmet) and recording the excitement with a GoPro camera. The canoe then turned east and sailed through the unruly swells of the river mouth. This was a most dangerous and delicate manoeuvre. If we went too close to land, the brown estuarine turmoil would devour us. If we went too far out, the incoming ocean swells would break over us. It was intense sailing and several surprise waves just appeared out of nowhere and crashed over our outrigger. After what was the longest half hour of my life, we were past the river mouths and steering towards Vailala.

Our risky exit was celebrated with sak sak (sago) and dirty watar (cola cordial). I warmly complimented my companions. The plan now was to sleep in Vailala, a village beside a river where the brothers had family. When we reached the estuary at 1.30 pm, it became evident that going inside the sandbank leading to the river would be too difficult – we needed protected waters to land the canoe. ‘How far to K-town?’ Sanakoli asked. I looked at my notes and said hopefully, ‘I think we can make it before dark.’

Five hours later, we approached Kerema, the capital of the Gulf area, which is a large bay almost entirely encircled by mountains. We could see the lights of the town being turned on as we approached the long white rows of inshore foam that were reflecting the rapidly receding rays of the day. As we neared the entrance, the waves grew – as did our anxieties. ‘These waves are too much, nowhere to go in,’ Sanakoli said, looking concerned. Trying to navigate those breakers in the dimming light at this time of year would be virtual suicide. There was little we could do except go back out to sea and take our chances overnight in the Gulf, hoping that the wind wouldn’t pick up – and that we didn’t disturb the legendary giant stingray the locals had warned us about.

Clouds of hypnotic marine

shimmered in our wake, lighting up the hull

01

02

This was the beginning of a mysterious night. It was a new moon so there was little light; instead, the mountains began to spit winds at us in strange gusts. We came dangerously close to two fishing trawlers who didn’t seem to notice our lantern or heed my calls on the VHF radio as they hummed past us. The wind then became steady and Tawali Pasana shot up along the undefined coast, dodging a breaking reef – again, at the last minute. A strange cold rain began to fall in sheets and as it passed, clouds of hypnotic marine bioluminescence shimmered in our wake, lighting up the hull. Then the wind suddenly subsided and Justin handed me the sheet and went instantly to sleep in the front of the canoe.

It was long past midnight, but well before dawn. Sanakoli was sitting by the yabby yabby, nodding off. Then I noticed someone cooking on the outrigger platform. It was an old lady. She seemed familiar – it was the same ghostly old woman I had previously seen when we were sailing off Um Island, Sorong, West Papua. I felt that having a good meal was just what we needed. I could feel the warm fire. Then I snapped out of it, as if waking from a dream. I turned my headlight onto the platform; there was no one there. As morning came, we were bobbing through a clear turquoise sea and the land looked different. The Fellowship of the Tawali Pasana had made it through the mighty Gulf of Papua – and during the treacherous south-easterlies. Perhaps the spirit mothers really were looking after us. Of that, Sanakoli and Justin had no doubt.

My companions were used to navigating through their home islands by sight and what I can best describe as instinct

01

Completion of the

02

Hand-drawn map by Thor F Jensen.

The Fellowship of the Tawali Pasana had made it through the mighty Gulf of Papua

On 4 October 2017, we arrived at Inuoro Island and thus we had crossed the border into Milne Bay Province, although the sailors were of the opinion that Milne Bay first started on the Suau coast. As we approached the beach, the wind disappeared –we were in lee of the island, almost touching the coral beach. I was standing ready to jump ashore when a strong current suddenly took our bow and started sweeping us along the beach toward a section of breakers. ‘Damn,’ I thought. But a local kid had seen it all and reached his hands out. I threw the line and he tied us off to a coral head. Yet another close call.

The next morning, we sailed out. The weather forecast didn’t look that good, although we thought we could manage. Leaving Inouro Island went well as the reef protected our launch from the incoming waves but, as soon as we were free, the waves grew, although at that stage, everything was still manageable. ‘Kisoo,’ Justin suddenly yelled. Our nylon fishing line tightened. I untied the string from the mast just in time for a fish to make a violent jerk that burned my hands. I almost lost the reel. ‘Ha ha, that is the pain of the fisherman,’ Justin mused. After some minutes, and an explosion of adrenaline, I heaved in a one-metre-long mackerel. ‘You watch the teeth, they are like razors,’ Sanakoli warned.

The big fish was thrusting violently. Sanakoli pulled the line and, as the spear-like head came out of the hull, I dispatched it with two sharp blows to the head using a piece of firewood. ‘Ho hoo,’ Sanakoli yelled, ‘Now we are home. That’s how we fish in Milne Bay Province.’ Justin joined in. ‘Gulf nothing. Central Province, small fish. Milne Bay, we catch big fish.’ We were all excited but the joyous hype soon evaporated. As I scooped the blood off the deck, the wind started to gust so we made a jaya-towa and went inwards. Here, a sandbank created a nasty chop, so we went outwards again where the waves had grown even bigger. There was nothing to do but diligently jig-jag (tack) while trying to navigate between the two extremes.

We suddenly found ourselves in a very bad situation. The waves were tall and short and angry. The two brothers did their best but the sea was breaking on the outrigger with a force that rattled the whole canoe. We heard a flapping noise. The black plastic had given in and a two-metre-long slit appeared in the sail. There was no time to spend on this as swells broke on the bow and our water containers started to float in the hull. I dumped the bailer and got to our bilge pump. I was getting a now familiar dire feeling and started to think, ‘How much pounding can our Tawali Pasana take?’ The dreadful answer came soon enough. Justin yelled in the Bwanabwana language. Sanakoli turned his head and looked shocked. I followed his red eyes. Disaster! Two poles had already broken off from the outrigger. I looked around. We were surrounded by high seas, six nautical miles from land and the same distance to our next destination of Bona Bona. My heart sank as I instantly recalled Bula, where we had refitted the outrigger … and Justin’s cautionary words – ‘You tie them strong, if one break, all soon break. And we sink.’

Shortly after this episode, Thor F Jensen, Justin John and Sanakoli John completed their historic voyage, which generated enormous media coverage and inspired the young people of New Guinea to celebrate their extraordinary seafaring culture.

Thor F Jensen is a Danish adventurer and award-winning filmmaker. To register for an author-signed first edition of his book, please visit saltwaterandspeartips.com

Thor F Jensen wishes to thank culturalconsulting.com.au and Sophia Pascoe for editorial assistance.

Writers, publishers and readers of maritime history are invited to nominate works for maritime history prizes totalling $7,000, sponsored jointly by the Australian Association for Maritime History and the Australian National Maritime Museum. Nominations for the 2019 round close on 31 July 2019.

EVERY TWO YEARS, the Australian National Maritime Museum and the Australian Association for Maritime History sponsor two prizes: the Frank Broeze Memorial Maritime History Book Prize and the Australian Community Maritime History Prize. Both reflect the wish of the sponsoring organisations to promote a broad view of maritime history that demonstrates how the sea and maritime influences have been more central to the shaping of Australia, its people and its culture than has commonly been believed.

The major prize is named in honour of the late Professor Frank Broeze (1945–2001) of the University of Western Australia, who has been called the pre-eminent maritime historian of his generation. Professor Broeze was a founding member of the Australian Association for Maritime History and inaugural editor of its scholarly journal The Great Circle, and introduced Australia’s first university course on maritime history. He wrote many works on Australian maritime history, including the landmark Island Nation (1997), helping to redefine the field in broader terms than ships, sailors and sea power. He reached into economic, business, social and urban histories to make maritime history truly multidisciplinary.

This will be the eighth joint prize for a maritime history book awarded by the two organisations, and the third community maritime history prize.

The 2019 Frank Broeze Memorial Maritime History Book Prize of $5,000

To be awarded for a non-fiction book treating any aspect of maritime history relating to or affecting Australia, written or co-authored by an Australian citizen or permanent resident, and published between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2018. The book should be published in Australia, although titles written by Australian authors but published overseas may be considered at the discretion of the judges. The prize is open to Australian authors or co-authors of a book-length monograph or compilation of their own works.

Fictional works, edited collections of essays by multiple contributors, second editions and translations of another writer’s work are not eligible.

The 2019 Australian Community Maritime History Prize of $2,000

To be awarded to a regional or local museum or historical society for a publication (book, booklet, educational resource kit, DVD or other print or digital media, including websites, databases and oral histories) relating to an aspect of maritime history of that region or community, and published between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2018. The winner will also receive a year’s subscription to the Australian Association for Maritime History and a year’s subscription to the Australian National Maritime Museum’s journal Signals

Publications by state-run organisations, physical exhibitions and periodicals such as journals are not eligible.

The two biennial prizes reflect the wish of the sponsoring organisations to promote a broad view of maritime history

to nominate

To nominate for the Frank Broeze Memorial Maritime History Book Prize, send one copy of the publication to the address below. Copies of any published reviews may also be included.

To nominate for the Australian Community Maritime History Prize, send a physical copy of print publications or DVDs.

For digital publications such as websites, databases, online exhibitions or apps, nominations must include 250–300 words explaining the vision and objectives of the digital media, plus data indicating its success. For websites and databases, also provide the URL or download details; for an app or other digital media, submit it on a USB. Copies of any published reviews may also be included.

Multiple nominations may be made, but each must be for one category only.

Nominations for both prizes close on 31 July 2019. They should be emailed to publications@sea.museum or posted to:

Janine Flew

Publications coordinator

Australian National Maritime Museum Wharf 7, 58 Pirrama Road

Pyrmont NSW 2009

Judging process

Following an initial assessment of nominations, shortlisted authors or publishers will be invited to submit a further two copies of their publication. These will be judged by a committee of three prominent judges from the maritime history community.

The judges’ decision will be final and no correspondence will be entered into.

The prize will be announced and awarded at a time and venue to be advised.

Judging of the 2017 awards

We regret that the judging of the 2017 awards has been unavoidably delayed. It is currently under way, however, and an announcement will be made as soon as possible.

Previous prize winners: In All

Respects Ready by David Stevens, winner of the 2015 Frank Broeze Book Prize, and Sea of Dreams , winner of the 2013 Australian Community Maritime History Prize.It is clear that Australian society is undergoing a sea change, balanced uncertainly between the desire to honour the past but mindful of the need to embrace the future

In a multicultural country increasingly aware of the history and cultures of its First Peoples, how relevant is Australia’s colonial (British) history? Head of Research Dr Nigel Erskine profiles three recent events and how they relate to notions of our national identity.

THE COINCIDENCE OF THREE IMPORTANT EVENTS in January this year provided a rare moment to reflect on Australian history and its ongoing relevance for Australians today. The first of these is Australia Day, which, since 1988 – the bicentenary of European settlement – has become a major public holiday and national anniversary. It is celebrated on 26 January, the date on which the colony of New South Wales was officially established with the raising of the Union flag in Sydney Cove in 1788.

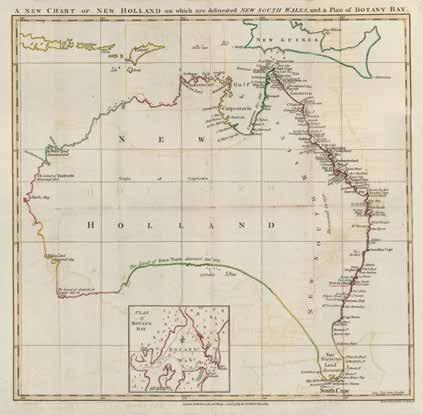

Before 1988, 26 January tended to be looked at as a singularly New South Wales anniversary, leaving the other six states and territories to celebrate anniversaries relating to their own distinct colonial foundations. The initial British settlement in Australia was confined to the east coast of the continent, the part claimed by Lieutenant James Cook in 1770 during his survey of the east coast on board the bark Endeavour. By 1787, the territory of New South Wales had grown considerably and extended from 10 degrees 27 minutes south (Cape York) to 43 degrees 39 minutes south (South Cape) to 153 degrees east (halfway across South Australia). It also included all the adjacent Pacific islands within these latitudes.

The second event of note that occurred in January was the discovery of the grave of Captain Matthew Flinders in London. It was announced on 25 January, only a day before the anniversary of the foundation of British settlement in Australia. The timing could not have better, and the event was major news across Australian media.

Of all the early British naval figures who explored Australia’s coasts after Cook, Matthew Flinders looms largest. He sailed to New South Wales in 1795 aboard HMS Reliance, bringing the new Governor, John Hunter, to the colony. Also aboard Reliance was surgeon George Bass. Over the next five years Bass and Flinders completed a number of small-boat expeditions, including the circumnavigation of Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) in 1798. As a result of this work Flinders was promoted lieutenant and in 1800 returned to England with an ambitious plan to survey the entire coast of Australia. At that time, most of Australia’s south coast remained unexplored by Europeans. Large sections of the west and north coasts had been mapped by the Dutch, and Cook had mapped most of the east coast, but no single survey of the entire coast existed. The Admiralty agreed to place Flinders in command of a ship. They provided the armed vessel Xenophon, refitted it for a voyage of discovery and renamed it, appropriately, HMS Investigator

01

Map from 1787. New South Wales is marked with places named by Cook; New Holland, as the rest of the continent was then known, bears names given by Dutch explorers the previous century. Matthew Flinders was yet to circumnavigate Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) and determine that it was an island. British colonial expansion and gradual claim to the entire continent progressed throughout the 19th century. ANMM Collection 00000368

02

Colonial Wallpapers: Pacific Encounters , Helen Tiernan, 2017. Based on the conventions and elements of early European sea charts, this work takes as its starting point the panoramic French wallpaper design produced in 1805, Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique, which illustrated Captain James Cook’s voyages around the Pacific. It combines images from these voyages with the mythical, romantic and ridiculous to question the depiction of the Pacific that explorers brought back to Europe during the ‘Age of Discovery’. ANMM Collection 00055114 Funded by ANM Foundation. © Helen S Tiernan

Of all the early British naval figures who explored Australia’s coasts after Cook, Matthew Flinders looms largest

01

The breastplate found on Flinders’ coffin. It reads simply ‘Capt n Matthew Flinders RN Died 19 July 1814 Aged 40 Years’. Image courtesy HS2

02

As part of preparatory works for the high-speed London to Birmingham rail link, archaeologists exhumed thousands of graves, among them that of Matthew Flinders, at London’s Euston railway station. Euston Station opened in 1837, and when it was expanded 50 years later, platforms were built over the adjacent St James’s Church burial ground, where Flinders had been buried in 1814. Image courtesy HS2

Despite its great achievements surveying on the south and east coasts of Australia, the expedition was severely hampered by the poor and worsening condition of the Investigator By the time Flinders reached the Gulf of Carpentaria in 1803, he decided the ship was too unseaworthy to continue. Flinders and Investigator ’s crew survived the counter-clockwise voyage around Australia to return to Sydney, but unfortunately were wrecked on an uncharted reef in the Coral Sea only a few weeks later, aboard HMS Porpoise on the passage home to England. Flinders later wrote an account of this journey and his subsequent imprisonment on Mauritius in A Voyage to Terra Australis. He died, aged 40, the day after it was published.

The third event that occurred in January was the Prime Minister of Australia’s announcement of $48.7 million dollars of financial support to mark the 250th anniversary of Captain James Cook’s first voyage to Australia and the Pacific. Prime Minister Scott Morrison stated: ‘That voyage is the reason Australia is what it is today and it’s important we take the opportunity to reflect on it.’

The announcement provoked an immediate social media deluge of varying comments: outright support for the initiative, criticism at the ‘waste of taxpayer money’, outrage at the inappropriateness of funding an anniversary regarded by many Indigenous Australians as the beginning of the end of their culture, and the question ‘Who was Captain Cook’?

Like all societies, Australian society is complex and dynamic, continually changing in response to political, cultural and financial influences that affect the way Australians view our history, and our present and future place in the world.

In 1788, when the colony of New South Wales was formed by just over 1,000 convicts, guards, and administrators on the other side of the world from Europe, it was totally dependent on Britain for supplies, the vast majority of the new arrivals were British, and Captain Cook had been dead less than ten years. Locally, around the new settlement in Sydney, the arrival of Europeans had a devastating impact on the traditional inhabitants, with the introduction of smallpox estimated to have killed at least 50 per cent of those living around Sydney Harbour.

From about 1815 the European population of Australia grew rapidly and by 1820 numbered over 33,000. In each successive decade it continued to more than double, so that by 1850 it exceeded 400,000.

Throughout its colonial period (1788–1901) Australia depended on Britain for its security. It established legal and political systems that mirrored those in Britain, and in 1901, when the Australian colonies voted for independence from Britain, they did so in the understanding that Australia would continue to pay allegiance to the British monarchy through the office of the Governor General of Australia.

The real measure of the success or failure of the 2020 commemorations will be the overall response of Australians to this latest anniversary

01 Australia Day protest march in Melbourne. In recent years Australia Day celebrations have increasingly polarised the population and seen calls to either scrap the national foundation-day holiday or change its date. Image Shutterstock.com

02

Group of male migrants on the deck of MV Napoli, 1951. Part of a collection of items donated by Davide Ellero, who migrated from Italy to Australia in 1951 on board Napoli to work on the Snowy Mountains Hydro Electric Scheme. ANMM Collection 00003536

Australia’s loyalty to Britain was beyond question during the First World War, during the course of which more than 60,000 Australians were killed and 156,000 wounded or taken prisoner. For Australia, with a population of less than five million at the time, the impact on society was profound and the legacy of that sacrifice has become an integral thread of our national identity.

A critical turning point for Australia in its international relations came with the entry of the USA into the Second World War in 1941. The fall of ‘Fortress Singapore’ in 1942 demonstrated clearly that Britain was unable to protect its interests in the Indo-Pacific, heralding a new era when Australia increasingly turned to the United States. In 1951, Australia signed the Australia, New Zealand and United States Security (ANZUS) Treaty, agreeing to co-operate with the USA in military matters. In the 68 years since, Australia has supported the United States in conflicts from South-east Asia to the Middle East.

In the post-war period Australia opened its doors to European migrants seeking to rebuild lives shattered by the war and between 1947 and 1970 more than three million people migrated to Australia – initially from northern European countries, later from southern and eastern Europe, and later still from the Middle East and Asia.

In the 12 months to June 2018, migrants from China and India represented the highest percentage of new migrants to Australia, followed by those from the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Nepal, Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam and the United States.1

At 30 June 2017, people born in England continued to be the largest group of overseas-born residents (4.1 per cent of the total population) but had declined in the decade since 2007, when they represented 4.6 per cent of the Australian population. 2 That decline is expected to continue.

For Indigenous Australians, the pace of change in the postwar period has been much slower, with landmark moments including the right to vote (1962); the right to be included in census population figures (1967); the Mabo land-rights decision by the High Court of Australia (1992); and, in 2008, the apology to Indigenous Australians of the Stolen Generation by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd and the High Court’s Blue Mud Bay sea rights decision. However, while political change has been slow, Australian society more generally has developed a much greater awareness of Indigenous culture and its increasing visibility and incorporation into the national vision of Australia.

Reflecting back on the three events in January, in light of shifting attitudes – our increasing detachment from Britain and declining migration from the UK to Australia, our national embrace of multiculturalism, and our growing desire for greater Indigenous inclusion – it is clear that Australian society is undergoing a sea change, balanced uncertainly between the desire to honour the past but mindful of the need to embrace the future.

Captain Cook’s contact with Australia was limited to the east coast, but for the purposes of marking the milestone 250th anniversary nationally, the Australian government has committed funds for the replica of Cook’s ship Endeavour to circumnavigate the entire country. It anticipates that the vessel’s visits to each state and territory will reinforce the national significance of Cook’s voyage as the event that led to the foundation of European settlement in Australia. However, irrespective of political will and government support for the 2020 anniversary, the real measure of the success or failure of the 2020 commemorations will be the overall response of Australians to this latest anniversary.

Australia in 2019 is a very different society to that which existed at the time of the bicentenary more than 30 years ago, with many people now calling for events that are more broadly inclusive and relevant to a greater cross-section of modern Australian society. James Cook, Arthur Phillip and Matthew Flinders will always have a place in Australian history, but Australians’ responses to the 2020 anniversary will play a major role in deciding how we honour our British heritage in years to come.

1 Australian Demographic Statistics, June 2018, Australian Bureau of Statistics 3101.0

2 Australia’s Population by Country of Birth, ABS 3412.0 Migration, Australia 2016–17

Boot Reef is a perfect ship trap – difficult to see, imperfectly charted and lying across one of the main entrances to Torres Strait

In December 2018, a team from the Silentworld Foundation and the Australian National Maritime Museum located a mystery shipwreck at Boot Reef off Australia’s far north-east coast. Archival research narrowed its possible identity to one of a small handful of wrecks from the early 19th century – foremost among them a site first reported in 1891, which, according to legend, contained a hoard of silver coins that came to be known as the ‘Jardine Treasure’. Authors Kieran Hosty, Dr James Hunter, Irini Malliaros and Paul Hundley were members of the expedition.

Irini Malliaros , Jacqui Mullen and Andrew White from Silentworld Foundation searching for ‘black reef’ on Boot Reef.BOOT REEF IS A DRYING REEF SYSTEM with two central lagoons. It is located 950 kilometres north of Cairns and some 30 nautical miles (56 kilometres) east of Yule Entrance at the extreme northern end of the Outer Great Barrier Reef.

The reef was given its European name by Lieutenant Matthew Flinders, who passed it in 1803 in the Colonial Government Schooner Cumberland on his way to England. Flinders had recently been rescued following the disastrous wrecking of HMS Porpoise and the merchant vessel Cato on Wreck Reefs in August 1803 (see Signals No 90).

In 1891, the crew of a bêche-de-mer (sea cucumber) fishing vessel, Lancashire Lass, located the remains of an early19th-century vessel on a remote coral reef in the northern approaches to Torres Strait. Lancashire Lass was captained by Sam Rowe and owned by Francis (Frank) Lascelles Jardine, a pastoralist and plantation owner from Somerset, Queensland. The shipwreck site was discovered while the crew of Lancashire Lass – which had been pushed across the reef top into an enclosed lagoon during a tropical storm – attempted to cut a channel through the reef to extract their vessel.

Rowe and his crew recovered numerous items from the wreck, including an ‘old-fashioned’ anchor, a small bronze gun and several thousand Spanish silver coins minted between 1713 and the mid-1820s. Six boxes of specie (coins) were later exported from Mer (Murray Island) on 22 May 1891 and sent to England via the steamer Tara. According to the Pall Mall Gazette of 5 January 1892, Tara later landed a large quantity of specie –which the newspaper called the ‘Torres Strait treasure’ –with a value of £6,600 (equivalent to at least $1 million today). Colonial newspapers such as The Sydney Morning Herald and the Morning Bulletin took up the story, and the legend of what became known as the ‘Jardine Treasure’ was born.1

In newspaper accounts reporting the discovery, Rowe and Jardine speculated that the large number of Spanish coins recovered from the wreck indicated it was a Spanish vessel – likely one that had left South America with the payroll for Spanish garrisons in either Mauritius or the Solomon Islands. For some unknown reason, the ship had ended up wrecked in the remote, far-northern Great Barrier Reef.

While willing to share some information, Rowe and Jardine were understandably reluctant to reveal the location of the shipwreck. They only stated that it was at ‘the very northern end’ or ‘the very outer edge’ of the Great Barrier Reef. The mystery of the wreck’s identity and location was compounded when Rowe was later murdered by the crew of his new lugger Wren in 1893. 2

That’s where the story of the Great Barrier Reef’s ‘mystery Spanish wreck’ might have ended, had the Australian National Maritime Museum and Silentworld Foundation not commenced a long-term research project in 2012 to investigate shipping routes through and around the Great Barrier Reef that connected 19th-century Australia with the rest of the world.

Colonial newspapers took up the story of the shipwreck haul, and the legend of what became known as the ‘Jardine Treasure’ was born

Descending off the western side of Boot Reef, expedition divers located a second long-shanked anchor in 39 metres of water. Pictured is Kieran Hosty (ANMM).

As part of their archival investigations into historic shipwrecks along these maritime routes, the team came across several mentions of the lost ‘Spanish shipwreck’ and uncovered a tantalising clue to its possible whereabouts in the collection of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (Powerhouse Museum) in Sydney. Object N12662 is described as a ‘Coin, Spain, Ferdinand VII (1808–33). Dollar, Mexico Mint, 1817 found Boot Reef Torres Strait by Capt Rowe of Lancashire Lass.’ 3

The generous sponsorship of the Silentworld Foundation enabled the project team to survey Boot Reef last December to follow up these leads. Maritime archaeologists, researchers and staff from the Silentworld Foundation and maritime archaeologists from the Australian National Maritime Museum joined MV Silentworld at Thursday Island and commenced a 24-hour passage through the eastern Torres Strait and beyond the outer edge of the Great Barrier Reef to the remote atoll.

Upon arriving at Boot Reef, we were pleased (and somewhat amazed) to find near-perfect weather conditions; the sea was flat and glistening in the tropical sun, with only a slight swell barely breaking to indicate the edge of the reef. While pleasant, these conditions also highlighted what a perfect ship trap Boot Reef could be, as it was difficult to see, imperfectly charted and lying across one of the main entrances to Torres Strait.

Our search for an anchorage emphasised the hazards posed by Boot Reef during the 19th century. No shallow-water anchorages exist at Boot Reef because it is a seamount with near-vertical walls that rapidly rise from a depth of 1,500 metres to a narrow plateau less than 100 metres wide at 90 metres depth. From this point, the seabed again rises vertically to sea level. Armed only with a 50-fathom (90-metre) sounding lead and relatively inaccurate charts, 19th-century sailors would have been caught completely off guard if they encountered the reef at night or in dead-calm conditions.

With no anchorage available, we decided to anchor inside the lagoon of nearby Ashmore Reef (see Signals No 112) at night and make the 10-nautical-mile (16-kilometre) journey to Boot Reef each morning.

One of our first tasks was to circumnavigate Boot Reef in Blackwatch, the largest of Silentworld ’s three tenders. Because Boot Reef has a perimeter of more than 18 nautical miles (33 kilometres), this took several hours but allowed us to visually scan the reef top and look for signs of shipwrecks, including anchors, anchor chain and ballast mounds. It also facilitated collection of a series of GPS plots for the outer edge of the reef, which could be used for mapping once fieldwork was complete. Meanwhile, John Mullen of Silentworld Foundation managed to pilot the project’s remote-sensing survey vessel Maggie III over the reef top into the smaller of Boot Reef’s two completely enclosed lagoons. An investigation of the area located a few promising magnetic anomalies that could indicate the shipwreck discovered by Rowe.

With more fine weather the next day, the team continued the remote sensing survey along Boot Reef’s western side. The crew aboard Blackwatch towed the magnetometer along the outer and northern areas of the reef, while those on Maggie III surveyed the two sheltered, but surprisingly deep, lagoons. They also investigated areas on the reef flat which, in 2017, had been identified by maritime archaeologists from Silentworld Foundation and the Australian National Maritime Museum through satellite imagery as possible locations of a phenomenon known as ‘black reef’ – a consistent pattern of dark discolouration on the reef flat that correlated with the plotted locations of historic shipwreck sites.

Black reef is observed at sites of modern shipwreck or natural disaster.4 The relationship between black reef and shipwrecks has not been well studied, and research is ongoing. However, current and past investigations have noted a biological ‘phase shift’ in affected reefs, 5 in which a coral-dominated benthic ecosystem (inclusive of microalgae) is replaced by a predominantly (macro)algal one in response to stresses such as pollution via run-off, severe storm damage and shipwreck.

Black reef was not observed or recorded during the 2017 field season at Kenn Reefs, as it only became apparent during postfieldwork GIS (Geographic Information Systems) analysis.

The effects of historic shipwrecks on coral reefs are poorly understood. A primary aim of the Boot Reef project was to collect samples and acquire empirical data to contribute to a broader understanding of the relationship between black reef and historic shipwreck sites. Our research also hopes to quantify the potential of black reef to act as a predictive indicator for locating shipwrecks. The ability to review satellite imagery before undertaking fieldwork and to select areas of interest based on the phenomenon’s presence could potentially revolutionise the way sites are located on the Great Barrier Reef and in the Coral Sea.

On the expedition’s fifth day, the magnetometer team found a series of significant magnetic anomalies on the western side of Boot Reef, along the upper edge of a near-vertical 90-metre drop-off. At the very same time, a team of snorkellers investigating a patch of black reef 50 metres to the east of these anomalies coincidentally located a run of anchor chain. Later in the day, the team aboard Maggie III found an early-19th-century old-pattern Admiralty long-shanked anchor lying on the reef top. The anchor appeared to be associated with, but was not physically connected to, the run of chain.

Aided by an aerial drone, additional magnetometer survey work and in-water searches, other shipwreck material was soon discovered, including copper-alloy hull fastenings, iron chain plates (used to attach the standing rigging to the hull of the ship) and a heavily eroded glass decklight.

The presence of an anchor and chain does not necessarily indicate a shipwreck site. It could instead mark where a vessel struck the reef and an anchor was used to ‘kedge’, or pull the hull into deeper water, before sailing away and leaving the anchor behind. However, the presence of the structural material strongly suggested that the vessel had endured significant damage and broke up as it was pushed across the reef flat.

With the anchor chain oriented almost directly east–west across the reef flat, the team investigated the area around either end in an effort to find the remains of the ship.

On the reef’s western side, the anchor chain was broken at the very edge of a 90-metre drop-off. Did this indicate the vessel had come from the east, struck the reef and bounced over the top, paying out its anchor and chain before either sailing away or sinking off the western edge of the reef? The only way to find out was to send teams of scuba divers down the drop-off to search for signs of the wreck.

01 Near the deep-water anchor, divers also discovered fragments of timber – an unusual find, given the warmth of the water and the presence of wood-eating marine borers. Pictured is Kieran Hosty (ANMM).

02

Libby Illidge (AIMS) and Jacqui Mullen (Silentworld) plotting the run of open-link anchor chain across the reef top. The anchor chain led the team to the drop-off and eventually the second anchor.

‘Black reef’ is a consistent pattern of dark discolouration on a reef flat that correlates with the plotted locations of historic shipwreck sites

The presence of an anchor and chain does not necessarily indicate a shipwreck site

01 For their orientation and equipment check dive, the expedition divers revisited the site of the Comet (1829) on Ashmore Reef.

02 Irini Malliaros (Silentworld Foundation) and James Hunter (Australian National Maritime Museum) recording one of the old-pattern Admiralty long-shanked anchors found on Boot Reef.

Recovered from the wreck were several thousand Spanish silver coins minted between 1713 and the mid-1820s

Given the extreme water depth and Boot Reef’s isolation, this would be no ordinary reef dive. It required considerable planning and additional safety equipment, including emergency ‘bail-out’ air cylinders, in case the divers experienced equipment malfunction at depth.

Thanks to the reef’s excellent underwater visibility, the divers were able to scan the edge of the drop-off from sea level down to between 70 and 80 metres depth. They didn’t locate the shipwreck, but they did find a nearly identical Admiralty long-shanked anchor precariously perched on a coral ledge at 39 metres. Its presence, and the broken anchor chain on the reef flat almost directly above it, suggest that the vessel approached from the west and struck the reef’s western edge, where the crew dropped one of the anchors before running out its anchor chain. The vessel then appears to have slid eastward across the reef top, losing various structural components along the way.

A survey of the eastern side of Boot Reef located another scatter of shipwreck material in about two metres of water, including large iron keel bolts, mast rings, mast caps, lead shot, lead sounding weights and fragments of coal. At least two iron gudgeons (large hinges mounted on a ship’s stern upon which the rudder pivots) were also found, suggesting that the vessel’s stern section came to rest on the reef’s eastern edge. While the team did not find articulated timber hull components, evidence suggests that the Boot Reef shipwreck represents an early19th-century sailing vessel of some 200–300 tons that was copper sheathed and iron fastened.

Although the annotation associated with the silver coin in the Powerhouse Museum collection states that Rowe collected it from Boot Reef, the archaeological fieldwork conducted in December 2018 has cast some doubt on his assertions. While an early-19th-century shipwreck was located on the reef flat, the site does not resemble the description provided by Rowe in historic newspaper accounts. Also, archival research conducted by the team after the 2018 survey uncovered a 1911 statement by Frank Jardine that the shipwreck was located ‘in a lagoon of Portlock Reef’.6 This statement appears to contradict Rowe’s 1891 assertion that the wreck was located ‘on the extreme outer reef of the Great Barrier Reef Chain’. However, it is worth noting that Portlock Reef has historically been considered the extreme northern limit of the Great Barrier Reef.7

Whether or not the shipwreck found by Lancashire Lass was on Boot or Portlock Reef is a matter of conjecture, but there is reason to believe that it was the remnants of The Sun, an English-built, 185-ton brig that arrived in Hobart in early 1826 with a cargo of tea from China. It then sailed to Sydney, where its captain secured a cargo worth 30,000–40,000 Spanish dollars (equivalent to as much as AUD1.4 million today) in silver specie to deliver to Singapore. In December 1826, reports arrived in Sydney, via India, that The Sun had been wrecked on a remote coral reef near the northern entrance to Torres Strait. The entire crew appears to have survived and arrived at Mer after a twoday voyage in the ship’s boats. Tragically, 24 crewmen drowned when their boat capsized in the surf as they attempted to land.

Although it is difficult to confirm that Rowe and the Lancashire Lass crew found the wreck of The Sun, the type of coinage and its date range seem to favour the theory.

If the Boot Reef wreck is not the vessel located by Rowe, then archival research seems to indicate that it may be the Eliza (1815), Fame (1817), Henry (1825) or Venus (1826). These share many of the characteristics of the wreck found on Boot Reef, but only further research will be able to confirm its identity.

1 Most of the specie was sent by the Jardine family to England, but it is uncertain what happened to it.

2 The Brisbane Courier, 28 November 1893.

3 maas/291947, accessed 30 May 2018.

4 Hatcher, B, R Johannes and A Robinson (1989), ‘Review of the Research Relevant to the Conservation of Shallow Tropical Marine Ecosystems’, Oceanography and Marine Biology 27: 337–414.

5 Done, T J (1992), ‘Phase Shifts in Coral Reef Communities and Their Ecological Significance’, Hydrobiologia 247(1): 121–132.

6 The Brisbane Courier, 27 May 1911.

7 The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 May 1846.

Our work on Boot Reef would not have been possible without the generous support of our long-time research partner and major sponsor The Silentworld Foundation and the valuable assistance of John and Jacqui Mullen, Peter and Libby Illidge, Julia Sumerling, Andrew White, Captain Michael Gooding, Chris Ellis, Hamish Turvey, Shirley Puth, Victoria Miranda, Kamilah Fox, Maria Jose Gonzalez Rodri and Stephanie King.

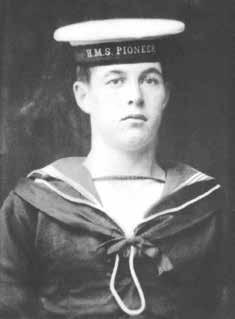

Since the wreck site of HMAS AE1 was found in December 2017, the stories of many of its 35 crew have been highlighted in the press. One crewman, however, has been largely overlooked. The only member of the submarine’s complement not born in either Australia or Great Britain, he was one of New Zealand’s first submariners, as well as the nation’s first combat casualty of World War I. His name is John Reardon. By Dr James Hunter.

Reardon quickly moved up the ranks, and within a year of commencing his five-year naval service he was rated an Able Seaman

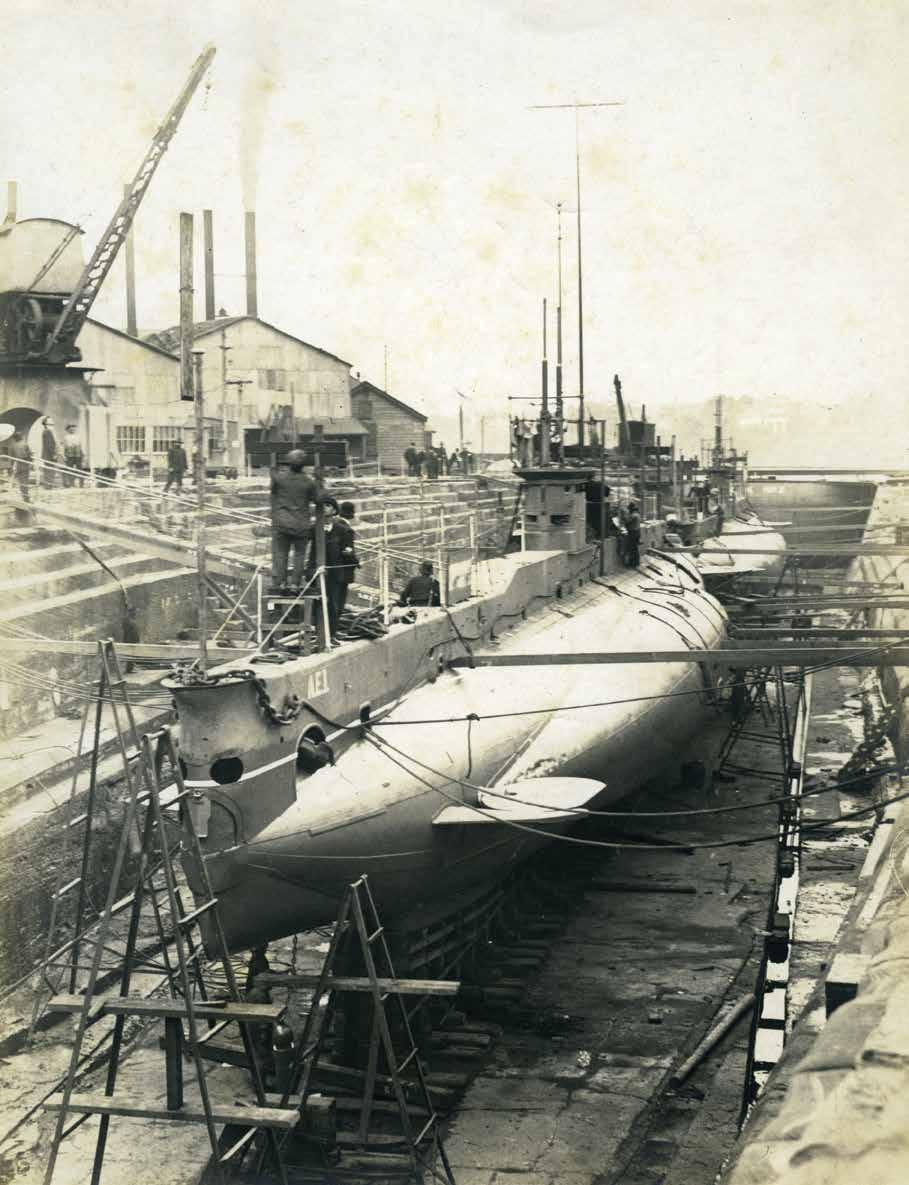

THE DISCOVERY OF THE WRECK SITE OF HMAS AE1 in December 2017 garnered significant media coverage within Australia and around the world. AE1 was the first submarine commissioned into the fledgling Royal Australian Navy (RAN), and would also become the RAN’s first wartime loss when it mysteriously disappeared with all hands off Papua New Guinea’s Duke of York Islands in the opening months of the First World War. Among myriad discussions ignited by AE1’s discovery were those related to its 35 crew members. All frontline RAN warships that served in the conflict were commanded by officers who were (predominantly) British in origin, while their crews comprised a mix of mostly British and Australian ratings, as well as smaller numbers of sailors from other colonies and dominions within the British Empire.

In the case of AE1, 18 men – or just over half of the submarine’s crew – were Royal Navy personnel from Great Britain. Sixteen others were members of the RAN, of whom six were from the British Isles and had formerly served in the Royal Navy. Ten of AE1’s complement were Australian-born and hailed from New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and Tasmania. A number of these men – ranging from the submarine’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Thomas Besant, to Able Seaman James Thomas – have recently had their stories highlighted in the Australian press. One crewman, however, has been largely overlooked in the media coverage of AE1 Often (anonymously) referred to as ‘the New Zealander’, John Reardon was the only crewmember not born in either Australia or Great Britain, and his story – like those of his fellow crewmen – is unique and significant.

Origins and early naval career

John Reardon was born on 9 February 1891 in Kaikoura on New Zealand’s South Island, the third son of Edward and Catherine Reardon. New Zealand was then in the midst of an economic depression and suffering from severe work shortages; consequently, Edward Reardon was unable to find employment in Kaikoura and sought work in the South Island port of Lyttelton. He later moved to Wellington, where he found work as a messenger in the Government Insurance Office. Catherine and the children remained in Kaikoura, where they were assisted by extended family. This support system proved essential when Edward Reardon suddenly collapsed and died of heart failure on Wellington’s Taranaki Street on the night of 12 November 1895. Reardon, who was ‘about 50 or 51 years of age’ at the time of his death, had recently suffered a bout of influenza, and a coronial inquest noted that ‘acute congestion of the lungs’ was likely a significant contributing factor.1

Back in Kaikoura, Catherine and the children were devastated by Edward’s death, but with the assistance of extended family avoided destitution. Catherine eventually remarried and had four more children. John Reardon, meanwhile, was educated in Kaikoura and completed his Standard 3 exams before leaving school in 1906 at the age of 15. He worked as a labourer and in the local fishing industry for a brief period before answering a newspaper advertisement in early November 1907 seeking recruits for the Pelorus class light cruiser HMS Pioneer. One of a number of warships assigned to the Royal Navy’s Australian Squadron during the first decade of the 20th century, Pioneer operated primarily as a drill (training) ship and was usually stationed in Sydney, but made occasional visits to New Zealand ports. On 21 November 1907, Pioneer arrived at Lyttelton, where it tied up at the port’s ‘Skeleton Breastwork’ berth. Reardon was also in Lyttelton by this time, and reported to the ship for assessment. After a brief interview and medical examination, he was entered on Pioneer ’s crew roster as a Boy 2nd Class – the lowest rank for incoming naval personnel aged 15 to 17.

Reardon quickly moved up the ranks, and within a year of commencing his five-year naval service (which officially began on his 18th birthday in February 1909) he was rated an Able Seaman. He remained aboard Pioneer during this time as the vessel transited between Australia and New Zealand, and made a lengthier return voyage from Sydney to Colombo, in Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka). Once back in Sydney in mid-1909, many of Pioneer ’s crew were transferred to other ships, but Reardon was retained to assist with instructing the next influx of trainees – a testament to his skill and the high regard with which he was held by the ship’s captain, Commander William Frederick Blunt rn

01 AE1 at Portsmouth, UK, before its record-setting voyage to Australia. Image courtesy Sea Power Centre AE1 (front) and AE2 in Fitzroy Dock, Cockatoo Island, Sydney, June 1914.

AE1 (front) and AE2 in Fitzroy Dock, Cockatoo Island, Sydney, June 1914.

Those skills were put to the test in January 1910 when Reardon joined other crewmen from Pioneer in rescuing passengers and crew from the Union Steamship Company vessel SS Waikare. The steamer was returning to Dunedin from a tour of Fiordland when it struck an uncharted rock in Dusky Sound and began to sink. The captain beached the stricken ship, and Pioneer – which in a stroke of luck happened to be visiting the nearby port of Bluff – was asked to assist in a rescue operation. All of Waikare ’s 141 passengers and 85 crew were safely recovered from the wreck and embarked aboard Pioneer. Reardon was a crewman aboard one of the rescue boats and was awarded 12 pounds 10 shillings in prize money (the equivalent of about $1,700 today) for his participation.

On 6 February 1911, Reardon was posted to the Challenger class protected cruiser HMS Challenger along with 13 other Pioneer crewmen. All had volunteered to transfer to the newly established Royal Australian Navy and journeyed to England aboard Challenger during the latter half of 1912. Following his arrival at Devonport, Reardon remained in Royal Navy service until 1 January 1913, when he joined the RAN as an Able Seaman for an enlistment period of five years. His naval records describe him as 5 feet 10 inches (178 centimetres) tall with dark brown hair, hazel eyes, and a ‘fresh’ complexion. 2 Reardon’s skin tone and flushed cheeks were among his most notable physical characteristics, and earned him the nickname ‘Rosy’ among his shipmates. 3 Another physical attribute noted in his RAN service record was a tattoo on his left forearm that depicted ‘clasped hands over [an] anchor’.4

Upon enlisting in the RAN, Reardon was assigned to the London Depot to commence submarine training, which he completed on 30 March 1913. He also qualified as a Seaman Torpedoman, which meant he would have been directly involved with the operation and upkeep of torpedoes, torpedo tubes, and the compartments where the torpedoes and their warheads were stowed when not in use. Upon graduating, Reardon was nominated for service aboard AE1, which was then being completed at the shipyard of Vickers Ltd in the English port of Barrow-in-Furness. Following the submarine’s launch on 22 May 1913, Reardon joined its commissioning crew and participated in a series of sea trials and working-up voyages. He was one of two New Zealand-born sailors to be trained for the RAN’s submarine service (the other was Stoker Archibald Wilson, who was assigned to AE1’s sister submarine, AE2) and would be aboard AE1 during its record-setting 83-day delivery voyage to Australia in early 1914.

John Reardon was one of two New Zealand-born sailors to be trained for the RAN’s submarine service

Following the submarine’s arrival at Sydney on 24 May, Reardon was assigned to the submarine depot ship HMAS Penguin AE1 was transferred to Cockatoo Island Dockyard, where it underwent refit, while Reardon enrolled in additional training and qualified as a Torpedoman, 2nd Class. During this period he also had a narrow brush with death, when a naval pinnace on which he was a crewman collided with the steamship Coombar on 9 June. The pinnace was transporting equipment from Cockatoo Island to Garden Island when it altered course to avoid a collision with the ferry Kal Kal near Milson’s Point. In doing so, it inadvertently steered into the path of Coombar, which struck the pinnace amidships and caused it to sink almost immediately. Because the accident occurred at the height of winter, the waters of Sydney Harbour were very cold, and Reardon was described as ‘hampered with [his] clothes … half-frozen and almost exhausted’ when he caught a lifebuoy thrown from Kal Kal and was rescued. 5 An AE2 crewman aboard the pinnace, Leading Stoker William James Groves, was not so lucky and drowned. Reardon was later quoted by a local newspaper as believing the incident was ‘a good omen … that established for him the safety of a life at sea’ and that he was ‘convinced … he would not lose his life by drowning’.6

Sadly, this belief proved misguided: John Reardon would be lost at sea almost exactly three months later on 14 September 1914 and become New Zealand’s first-ever naval casualty and its first combat death of World War I. He was 23 years old.

References

1 ‘News of the Day’, The New Zealand Times , 15 November 1895.

2 Record of Service, John Reardon (Official Number 7474). National Archives of Australia A6770 (Service Cards for Petty Officers and Men, 1911–1970).

3 G Wright, Kaikoura Submariner: John (Rosy) Reardon. Printstop, Wellington, p 8.

4 Record of Service.

5 ‘Collision in Port: Pinnace Sunk’, Sydney Morning Herald, 10 June 1914, p 13.

6 ‘Believed in Omens: Seaman Reardon’s Conviction’, [Sydney] Sun, 20 September 1914, p 1.

Further reading

White, M, 2015, Australian Submarines: A History (2nd edition).

Australian Teachers of Media, Inc, St Kilda West.

Wright, G, 2014, Kaikoura Submariner: John (Rosy) Reardon Printstop, Wellington.

The model makers’ bench at the museum has been a much-loved fixture for many years. Behind the construction of these detailed scale models is a great deal of painstaking scholarship. With curator Dr Stephen Gapps, model makers Col Gibson and John Laing confirm some important details about one of Matthew Flinders’ vessels of exploration, the sloop Norfolk, in research they first began in 2004.

IN THE AUTUMN OF 1798, under the orders of the acting lieutenant-governor of Norfolk Island, Captain John Townson, convict workers built a small vessel from local timbers. The sloop was pushed out into the surf and sailed on its maiden voyage from Norfolk Island to Sydney – a distance of more than 1,600 kilometres – in June 1798.

But Sydney had been beset by convicts stealing vessels and trying to escape – most famously in 1791 by Mary and William Bryant, who sailed with their two small children and seven other convicts to Indonesia in an open boat. For various reasons, including a spate of ‘piratical seizures’ of vessels, colonial authorities had placed severe restrictions on boatbuilding in the colony. When Norfolk arrived in Sydney, it was immediately confiscated, having been built – unbeknown to Captain Townson – against Governor John Hunter’s explicit orders.

When Norfolk arrived in Sydney, it was immediately confiscated

Ocean-going vessels were in short supply in the colony and Hunter ordered that Norfolk be fitted out for a planned voyage under Lieutenant Matthew Flinders to confirm whether a strait existed separating Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) from the mainland, as Hunter himself had long suspected. He reported to the Colonial Office in England that he was ‘endeavouring to fit out a deck’d boat of about 15 tons burthen’ for this purpose. Flinders, along with George Bass and a crew of eight volunteer sailors, departed Sydney in October.

But more than a decade later, in 1814, Matthew Flinders noted that the Norfolk was a ship of 25 tons. Almost all subsequent historical references to the sloop Norfolk, presumably quoting Flinders, are to a vessel of 25 tons.

Before the model makers at the museum commenced hundreds of hours’ work on a scale model of the Norfolk, such a discrepancy in size needed to be explained. Hunter was a naval officer with considerable experience and, as governor, was unlikely to make an error of some 10 tons in his official reports back to England. But Flinders was a careful navigator and a thorough chart maker. He sailed the Norfolk on a long voyage from Sydney to Tasmania and became one of Australia’s most respected naval officers. Was the vessel lengthened at some point? Or could the meticulous Flinders have been wrong?

01 A figure on the deck provides human scale.

02

The fine and intricate detail of planking, hatches and ropes takes many hours of skilled work.

Images Jasmine Poole/ANMM

Master boatbuilder Thomas Moore was undoubtedly in charge of preparing the Norfolk at Sydney Cove for its voyage in October, making it as watertight as possible, as it had been discovered to be leaky on its journey from Norfolk Island. It would seem that with this and much other work to do on the vessel, including provisioning, it could not have been lengthened in the short time available.

There was some uncertainty in Flinders and Bass’s earlier reports on the Norfolk before 1814. Flinders had said in 1801 that the sloop Norfolk ‘was not of 25 tons burthen’, presumably meaning it was less than 25 tons. In a letter to Sir Joseph Banks in May 1799 – only four months after the event – Bass said, ‘A sloop of 20 tons burthen was fitted for the purpose. We passed through the [Bass] strait and returned by the South Cape of New Holland.’

In 1802, in An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, David Collins wrote that Norfolk was ‘only five-and-twenty tons in burden’, which he seemed to have obtained from ‘the accurate and pleasing journal of Mr Bass’. While we know Bass had previously described the Norfolk as of 20 tons, it remains unclear how Collins arrived at 25 tons. It certainly seems he may have influenced the later account of Flinders, who possibly consulted Collins’ work in compiling his A Voyage to Terra Australis (1814).

The first description of the colonial sloop Norfolk was as ‘a decked longboat’. At this time, ‘longboat’ was a specific naval classification, along with pinnace, jolly boat, launch, cutter and barge. While these classifications were rather loose at times and varied due to conditions, the naval officers in the colony certainly knew what a longboat was.

The ships of the First Fleet all carried longboats and the early colony in New South Wales used many, both open and decked, in exploration and cargo carrying. They were the largest boats carried aboard ships, sturdily constructed and meant to carry heavy loads and lay out anchors. The First Fleet flagship, HMS Sirius, had two longboats aboard that were the standard length for that size ship at that time, which was about 25 or 26 feet in length. By contrast Cook’s Endeavour had a longboat of 19 feet.

While their size varied over time, longboats had been a standard design for the navy for many years. The size may be described by length, which may mean length of keel, length of deck, or length between perpendiculars (BP). They were also often described by the number of oars pulled. Larger boats pulled 14 or 16 oars, sometimes with two or three masts with setting sails.

While there was some standardisation, the precise length of a longboat was often determined by the best tree that could be found. To sail the open seas, a 32-foot keel boat would have been preferred to a smaller boat. This would be similar to Governor Phillip’s 16-oared boat of about 34 feet overall length. This vessel lasted very well, as Collins noted in April 1791. Could it have been the model for the first vessel built on Norfolk Island, the sloop Norfolk?

One way to work out the length of a 16-ton vessel is to compare the tonnage and length of other known ships. Museum volunteer guides Pam Forbes and Greg Jackson compiled a database of information on more than 1,000 wooden sailing ships built before 1849, and with an equation relating tonnage and length, a predictive model can be used. In this, a 16-ton vessel such as the Norfolk would be about 34 feet in length with a beam of 9 feet 10 inches.

By comparison, a ship of 25 tons would have a length of 40 feet 6 inches with a beam of about 11 feet 11 inches. This does not appear feasible as a ‘longboat’ of this period – 40 feet in length is more consistent with the early coastal schooners such as the Francis, which had been sent out in frame from England. However, a decked longboat of about 34 feet and about 16 tons eminently suits the characteristics of the colonial sloop Norfolk. 02

While their size varied over time, longboats had been a standard design for the navy for many years

There is nothing like a good historical reconstruction to test the validity of academic theorising

Finally, there is nothing like a good historical reconstruction to test the validity of academic theorising around such matters. For the 200th anniversary of Bass and Flinders’ voyage to Tasmania in 1798, Captain Bern Cuthbertson had built a reconstruction of the Norfolk to re-enact the journey, described in detail in his book In the Wake of Bass and Flinders, 200 years on

In 1996, before the re-enactment, Cuthbertson had said:

There are no known plans or identified illustrations of Norfolk ... Various historians have described her as being of 16 tons or of 25 tons ... We have settled on dimensions of 35 feet by 11 feet beam with a draught of four feet. We believe the given figure of 25 tons refers to Norfolk ’s carrying capacity when trading to the Hawkesbury River and to the Hunter.

In 2006, he remained convinced the dimensions of the Norfolk replica were correct:

Having spent two years living with Norfolk and sailing her over 6,000 nautical miles without an engine, I consider 25 tons was a mistake … I have no idea how this could have been achieved. We carried 6 tons of lead, plus water, anchors, spars, rigging and gear. This made her displacement tonnage 16.

Cuthbertson was adamant: ‘If the replica was ballasted to displace 25 tons she would have had very little freeboard and would have been a dog to handle.’

The precise length of a longboat was often determined by the best tree that could be found

So how did Flinders get it so wrong? When he was writing his Voyage to Terra Australis for publication between 1811 and 1814, he was a very sick man. He died the day after his book was published, the result of a disease he contracted in the South Pacific as a midshipman serving under Captain Bligh.

The ship Providence ’s paybook noted that Flinders underwent at least two of Surgeon Harwood’s customary ‘cures’ for venereal disease – doses of mercury. It was more likely the remedy than the actual disease that killed him.

It seems reasonable to assume that Flinders’ memory in revising his story for publication was not as faithful as he would have wished. We are reminded of other errors: he got the length of Tom Thumb [II] wrong, and the schooner Francis was 44 tons, not the 60 he referred to.

The Norfolk had a short life, sailing for just over two years from June 1798 to November 1800. Despite stringent government regulations on shipping security, it had been ‘piratically seized’ by convicts in Broken Bay, north of Sydney, in late October 1800. But as with many attempted escapes from the colony, the convict pirates didn’t get far. The wreck of the Norfolk was found on the north side of the Hunter River, at Newcastle near the present-day town of Stockton, at a site still called Pirate Point.

The authors contend that all references above to the sloop Norfolk while it was still sailing are more accurate than reports made more than a decade later. We conclude that the original report to the British Navy should stand – that is, ‘Colonial sloop Norfolk, 16 tons’.

Even though Flinders published it once, and many authors since have quoted (and still quote) 25 tons, it should in fact be 16 tons. Indeed, it is practicably unfeasible for a decked longboat of those dimensions to have been 25 tons at that time.

The authors conclude that, perhaps surprisingly, the man who sailed the vessel around Tasmania in 1798 – Flinders – was wrong, and Governor Hunter was correct.

Notes

For extensive notes and further reading, readers are referred to the full version of this article, published in Academia, 12 September 2017: academia.edu/34554380/Flinders_and_his_Sloop_Norfolk_evidence _re-assessed

Col Gibson and John Laing wish to thank Australian National Maritime Museum curator Dr Stephen Gapps for his assessment of their conclusions. Please see Signals No 110 (March–May 2015) for an article about co-author John Laing, master mariner and model maker.

Autonomous vehicles – commonly known as drones – are revolutionising maritime industries and research. Aerial drones can improve surveillance, safety and efficiency; underwater drones can gather data for mapping and surveying work, and even search for missing aircraft. Dean Cook looks at the latest developments in maritime robotics.

A STEALTHY ELECTRIC SHIP navigates silently along the headland until its sonar detects an anomaly on the seabed.

A small team of propeller-driven robots is deployed automatically from port and starboard. The underwater robots receive their mission from the ship, divide up the tasks and dive to the bottom to interrogate the anomaly with an array of optical and acoustic sensors, then spread out looking for more. They may be looking for wreckage, an enemy submarine, a poorly mapped pipeline or an oil-well blowout, but the information that they collect is transferred back to the ship and relayed to a control centre on the other side of the earth. A flashing light on the console alerts the first human in the loop that the autonomous roving fleet has found something.

While we might not be there just yet, this vision of fully remote operations isn’t fantastical. Overwater and underwater, a rising tide of maritime robots is playing an ever-greater role in Australia’s maritime capability – and AMC Search, the training and consulting specialist division of the Australian Maritime College, is at the forefront of these scientific developments.

But the world of robotics poses a heady dose of confusion to the casual observer, starting with its various abbreviations (UAV, AUV), raft of overlapping names (drones, Autonomous Marine Vehicles, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, Unmanned Aircraft System) and distinctions that aren’t always well defined.

Despite the perplexing nomenclature, robots used above and below water fall into two distinct groups, albeit with very similar names.

The aerial drone is officially called an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle, or UAV. This can refer to any aircraft without a human pilot on board, but most recently has become synonymous with the small helicopter-like vehicles flown by millions of people around the globe. These consumer and commercial UAVs are operated by a ground-based controller. They can travel tens of kilometres away from their ground stations, beaming back real-time images and video.

In the maritime sector, UAVs are deployed for surveillance, safety and efficiency, explains Dr Joel Spencer, CEO of The Institute for Drone Technology: