15 minute read

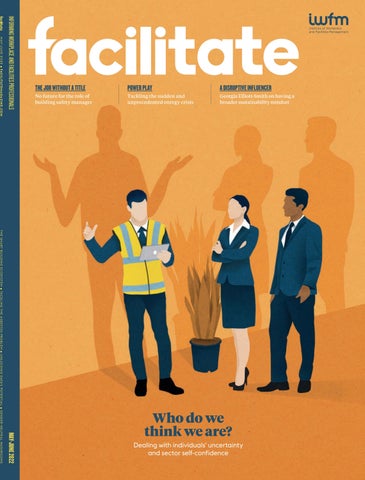

Who do we think we are?

From individually experienced ‘imposter syndrome’ to the sense of a lack of overall sector confi dence, workplace and facilities managers have often had to fi ght to determine how they and their work is perceived by others, internally and externally. Bradford Keen and Martin Read consider how they can instead be seen for the dynamism they routinely bring to their organisations’ performance and productivity

ILLUSTRATIONS: LOU KISS

WHO DO WE THINK WE ARE? Imagine it’s 1982 and you’re a facilities manager at a dinner party. Someone walks up to you and asks: what do you do for work? “You couldn’t answer in two or three words. It was as bad as that,” says one of the profession’s pioneers, Marilyn Standley. “In the beginning, we didn’t even have ownership of the term ‘facilities management’, far less ‘workplace and facilities management’. We didn’t know how to describe ourselves.” Defining, when asked, precisely what the profession does wasn’t easy. But while Standley felt moments of doubt in her career, she’d never have called it ‘imposter syndrome’, the term coined first as ‘imposter phenomenon’ in 1985 by US clinician Dr Pauline Clance, and which refers to the

fear of being found out as not being sufficiently capable, knowledgeable or worthy to fulfil a role.

Specific to the workplace and facilities management profession, Standley questions the relationship between imposter syndrome and whether or not the organisation considers the FM’s role to be core or non-core to its primary purpose – a lingering sense of being ‘outside of the loop’ and so not directly affecting their organisation’s purpose. “A lot of support functions are not seen as core, which may lead to people being less certain of themselves at work,” she explains.

Take a museum, for example. FM’s role in safeguarding the historical artefacts may not be seen as core to the organisation – that would rest with the conservation team – but FM would take care of fire safety, security, environmental conditions, which are all necessary conditions that need to be maintained to ensure the safety of the artefacts. FM, then, can be seen as core, or at least ‘core-adjacent’ – it just requires someone, and perhaps a particular type of character to champion the case (see box, ‘A complex situation’)

A question of belief

It’s worth reiterating at this point that ‘imposter syndrome’ as defined in 2022 is a sensitive psychological condition. The past few years have seen it increasingly recognised as a mental health issue, one brought to the fore through the experience of young people, in particular those newly entering the job market in these immediate post-pandemic times.

It has also, however, been a shorthand for describing that sense of being out of place, of questioning whether you either deserve or are sufficiently capable of carrying out a job. That’s been the experience of various FMs over the years; individuals inhabiting a role that did not exist before the 1980s, perhaps struggling to define the specifics of the role, to explain what they do to others, as in Standley’s case, or indeed to make their case today within the organisations they serve.

Conrad Dinsmore, head of projects at CBRE’s Facilities Management Division and a former IWFM newcomer of the year, says that he’s seen this feeling of imposter syndrome in people coming through graduate programmes. “People don’t know how good they actually are; but maybe that’s

JOB MARKET ASSESSMENT

THE RECRUITER’S PERSPECTIVE

“Imposter syndrome definitely exists within FM with some commentators even suggesting that the industry itself has imposter syndrome,” says Michelle Connolly, strategic development director of FM specialist recruitment firm 300 North.

“And Covid hasn’t made life any easier for those with imposter syndrome. While it has brought about greater recognition of the sector and opportunities within it,” Connolly argues, some managers might feel anxious trying to navigate an evolving role of hybrid working and changing workspaces, along with unoccupancy, energy management and so on.” To overcome this anxiety, Connolly’s advice to managers is to “curate the right team” and ensure that it is based on “mutual trust”.

Currently, says Connolly, it’s a candidate’s job market – and candidates know this. “Many are sure of their value, allowing them to consider all of their various options before taking on a new role,” she says. “Many are comfortable selling their skills to recruiters, particularly those who worked throughout the pandemic, and especially those who managed to change jobs during it.

“There is a flip side to this, however. Some people who were made redundant or spent much of the pandemic not working have found it has knocked their confidence and felt they needed to take on a role as quickly as possible, even if it meant going for something a step down from their previous role.”

Managers who join the FM profession without sufficient training or those who lack technical expertise may experience feelings of imposter syndrome when trying to oversee a team. Plus, reports of mental health concerns in the wake of the pandemic along with remotely managing team members have also contributed to a sense of doubt and anxiety in some, says Connolly.

Managing people is, of course, not the same as managing a building – but being adept at the former is increasingly more important as the numbers of qualified FMs increase and technical expertise is more routinely outsourced.

“Management throughout FM roles has o en become less technically focused,” says Connolly, “with people coming in from different talent streams including areas like so services and university tracks which has helped to lower the age of management teams and has broadened the experience they have, moving away from technical expertise.

“A management team should cover a range of experiences, including technical, but also should include people with good customer service skills, and those with an eye for numbers, able to deliver costeffective projects.

“Managerial confidence, largely, has shi ed to more individual skill sets, particularly as companies’ expectations for managers have changed and as the backgrounds and skills of managerial teams as a whole have changed.”

because they don’t know what good actually looks like,” he says – another issue we will return to.

Although contemporary imposter syndrome tends to be attributed to the young, Dinsmore believes that senior professionals, despite their experience, also suffer. “It’s maybe not reflected in certain parts of the industry or in certain organisations, but people are affected by it. They don’t truly understand what their next step should be or believe in their capabilities. You hear them saying, ‘I’ve been in this job for 10 years but I don’t know what’s next or whether I can do it’.”

Supply side FMs constantly questioned by increasingly inquisitive clients “could affect an FM who doesn’t trust or believe in what they know”, continues Dinsmore. Hasty and thus poor decision-making to reduce costs could be made, “or they might change the scope or approach to something that wasn’t best for that workspace just because the customer challenged their decisions”.

Generational differences

Much like Standley, Simone Fenton-Jarvis, workplace consultancy director for Relogix, believes that imposter syndrome is specific to the individual rather than the role, but tends to be more prevalent among “women and underserved populations”, with potential differences emerging when looking at sectors or verticals. “Certainly there are verticals that can fuel imposter syndrome,” she says. “For example, a working-class FM in a legal firm working alongside high-powered legal professionals. The imposter syndrome may be fuelled by the fact that they don’t feel as important, equal, or as intelligent”. Younger generations, Dinsmore reasons, tend to think of their professional trajectory as being projectbased, taking on stimulating roles to learn. “Then we want to move on to the next thing. That mindset has pushed young people not to be afraid to move faster onto new jobs.” Nevertheless, as new professionals emerge in the sector, armed with formal qualifications, they will arrive with the effective combination of “feeling competent and being competent”, contends Fenton-Jarvis, with the added benefit of the “wider organisation acknowledging such expertise too”.

“Where an organisation has the skill sets and qualifications in-house, I have seen the management team have more confidence and pride, feeling confident that they have the answers as a team,” she adds.

Qualifications and company recognition help, but it’s still up to the individual to adopt the mindset that they are suitably capable. Failure to do so might result in a workplace and facilities management professional who “devalues their role and the key part they play in the organisational functioning and employee experience”, says Fenton-Jarvis.

“This plays out in them not going for that promotion, not speaking up, not putting forward their innovative ideas, being self-critical and being the ‘FM ninja’ we always talk

about… just getting stuff done, staying quiet and ‘just doing their job’. It’s up to the organisation to acknowledge the role FM plays – and we all know how little that has happened in the past.”

Not so suite spot

Liz Kentish doesn’t care for the term ‘imposter syndrome’. The managing director at Kentish & Co thinks of the “internal conversation we’re having with ourselves” as being potentially positive or negative, depending on how severe it is.

A more positive spin, says Kentish, is having a healthy dose of self-doubt and introspective tendencies. “If it keeps us honest, it’s a good thing,” she explains. “If it keeps us striving to be better at what we do, and to have an even greater impact it’s a good thing.”

When imposter syndrome “rears its ugly head”, Kentish’s advice is to check in with ourselves and those we trust. “It’s important to have our tribe of people, your safe community of people who will be honest with you, hold the mirror up to you, and help you find what’s working.”

In 2020, Kentish launched Plan B, an FM mentoring programme. The more than 100 mentees have all been women but the

SECTOR CONFIDENCE

A COMPLEX SITUATION

Lionel Prodgers has been involved in shaping FM in the UK and internationally since its inception. He sees that there has been, and remains, a wider problem for the sector.

“Does the body of FM at large have an inferiority complex? I think you can see signs of it all the way through; as a body we’ve never really stepped up confidently,” says the managing director at consultancy Agents4RM.

One key issue from Prodgers’ perspective is a lack of consistency over the years as to where the workplace and FM function reports into in terms of corporate governance.

“You’d be surprised at the variety of organisational structures I’ve seen,” he explains. “I’ve seen FM reporting into personnel, finance, IT; sometimes directly to the CEO or COO; a whole range of areas where it fits, or perhaps doesn’t fit because no one knows where to put it.”

To Prodgers’ mind, this lack of consistency leads to individual FMs unable to collectively talk to their peers about the same things at the same level. Accordingly, this results in too much variation in how good the typical FM is at articulating their value proposition, the understanding of which is needed for wider organisational acceptance. It’s a classic catch-22.

Emerging governmental decrees about the environmental performance of organisations and the buildings they inhabit “are part of the solution,” accepts Prodgers. “The fact that corporates are going to have to report on environmental performance, FM should be rising to that challenge.”

But the sector “needs to come through with solutions that are generally accepted across the sector and that show to others we know how it should be done”. He adds: “It comes back to that inferiority complex, of not being confident enough.”

Prodgers believes that there is an underlying fear within the sector of being criticised (“that’s the impression I get; not enough boldness”) and that an insecurity exists that needs challenging by a more concerted effort at membership organisation level. Visible influencing of government policy must be the goal, but for Prodgers “the institutes who are representing the discipline aren’t really engaging in these issues.”

Charisma and authority The problem is compounded by the sector’s work continuing to suffer from being seen as dispensable whenever economic conditions, over which even the most brightly shining exponents have no control, suddenly conspire against them. Prodgers talks of extraordinary talents within FM, past and present, whose bodies of work have been undermined by such conditions and, most recently, the impacts of Covid-19. He likens this all too casual dismissal – of FMs who may have been improving processes in leaps and bounds – to the thought process through which an organisation decides it can blithely cut out its maintenance budget for a year and, having survived without consequence, try it again the following year. That this sense of dispensability continues to exist is a reason for any continuing inferiority complex and the need to fight it. individuals with the right combination of charisma and authority to break through this cycle are an important part of the solution, says Prodgers, not least because any FM proposing major projects “is going to need plenty of confidence in his numbers when dealing with the finance director”. “Without being too simplistic,” he continues, “the people who will shine through will always shine through; again it’s that combination of charisma or authority, if you like. And there are many examples in facilities management.”

mentors comprise women and men. “Imposter syndrome is prevalent at every level, and in every role. It’s just that some people don’t talk about it.

“Some people say it’s a gender thing. You read research saying that if a man and a woman go for the same job and the man’s only got 70% of what the job is asking for, he’ll apply anyway. And the woman won’t. I think that’s an urban myth. It comes back to character again; some of us just think we can learn with the help of a supportive organisation and a great manager. I truly believe we all, at times, suffer from imposter syndrome. But as I said, it’s not always a bad thing.”

One thing that won’t help is any lingering fixation of ‘recognition’ by the ‘C-suite’.

“I used to be convinced that it was all about getting FM a seat at the table, a voice in the boardroom,” says Kentish, “but I’m not convinced anymore that it’s as important.”

After all, “will having a voice in the C-suite help us work more collaboratively with our colleagues in HR and IT to create that workplace experience everybody wants? I’m not convinced that being visible at that level will drive those outcomes.”

The solution is in the data

There is a notion that FM, necessarily generalist as it is, is obliged to defer to the ‘experts’ it oversees and is thus less visible as a specific discipline. Could this have an impact on FM’s sense of imposter syndrome? Kentish has her doubts, but she asserts that FMs are specialists. It is perhaps ironic that the FM role of being a broad-shouldered generalist, commissioning and conducting the work of specialists, is in itself a specialist skill, albeit an invisible one to most. And yet, because of this intrinsic breadth of responsibility, the role may well be one that more routinely triggers feelings of self-doubt whatever the seniority level.

For both Kentish and Standley the answer, for individual practitioners and the wider sector, is to be found in the data analytics that environmental performance legislation obliges. Demonstrable truths exposed by data and necessarily addressable by the FM function will help. And ultimately, says Kentish, “you’ve got to have the evidence to quieten those voices in your head”.

For her part, Standley doubts whether the typical client-side FM has properly seized the outsourcing opportunity to the extent that they can free themselves to focus on the more pressing, strategic matters that quality time spent analysing performance data will expose.

“If you’re going to be seen as having successfully contributed to your organisation by outsourcing some of the more functional attributes of facilities and workplace management, you really need to be on top of your information and your data,” says Standley. “You need to find ways in which you can link that data to the key business metrics of success. I think that’s an interesting area for exploration because those metrics very often are performance-based, designed to enable the provider to get paid, as opposed to determining where they’ve brought success to the business.

“They’re more related to the performance of the outsource provider in delivering the KPIs than they are to delivering the business metrics. And I think one of our functions, if we’re in a small team managing a variety of outsourced arrangements, is how do you get those metrics to really translate into things that matter in the boardroom?”

It is this that, ultimately, that will settle any argument as to what the workplace or facilities manager brings to organisational performance – and how they themselves feel about the sector and the work they do within it.

SIMONE FENTON-JARVIS Workplace consultancy director for Relogix

MICHELLE CONNOLLY Strategic development director of FM specialist recruitment firm 300 North

MARILYN STANDLEY Non-executive director of IWFM and veteran of the profession

LIZ KENTISH Managing director at Kentish & Co

CONRAD DINSMORE Head of projects at CBRE’s Facilities Management Division

LIONEL PRODGERS Managing director at consultancy Agents4RM