8 minute read

We can all be public mental health workers

WE CAN ALL BE PUBLIC MENTAL HEALTH WORKERS

This past year, public mental health has been under the spotlight as perhaps never before. Clare Laker offers personal and professional insights into what it means.

Advertisement

I work in a local authority public health team. When I told people this a year ago, they would ask “What does that mean?”. I would explain that my role related to children and young people’s health and that I support work to promote public mental health. They would look blank!

Now, a year on, everyone has heard of public health and everybody is talking about mental health. When I say what I do now, people just reply “You must be busy.”

In the 2019 report 'What Good Looks Like' by the Association of Directors of Public Health, the authors explain that public mental health is a population-based approach to improving mental health and wellbeing. It encompasses primary (or universal) prevention – for example antistigma campaigns such as Mental Health Awareness Week; secondary prevention – providing targeted support to those at higher risk of mental health problems; and tertiary prevention – helping people who are living with mental health problems to stay well.

PUBLIC MENTAL HEALTH IN PRACTICE

Work such as Charlie Waller’s can promote mentally healthy schools, universities, and workplaces. Education staff can receive training to help them understand mental health issues and support young people better, and school nurses and counsellors can provide one-to-one support. Websites, podcasts and apps can also be helpful sources of support and information at this level.

For those who need more help, early intervention services supplement the important work of local Children & Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) providers, supporting people as they step down from in-patient care. Early intervention services include support for looked after children, those with special educational needs, those who have been bereaved and LGBT young people, as well as online and talking therapies.

Basically, public mental health is the same as public health as a whole: a discipline that aims to stop people becoming ill in the first place, helps prevent early symptoms from escalating and supports people in recovery. Specifically, it includes the following actions in relation to whole populations:

• Promoting good mental health and wellbeing

• Preventing mental health problems

• Preventing suicide and alleviating mental distress

• Improving the lives of people living with mental health problems

THE THREE TRUTHS OF PUBLIC HEALTH

Three broad truths underpin all public health work, including mental health.

Public health truth #1: our mental health fluctuates

Firstly, our health is not static. We all have mental health; sometimes it can be flourishing, sometimes it languishes; and what impacts my wellbeing may not have the same effect on yours. Some of us experience mental ill health which, if treated and managed, need not damage our lives. All of us experience difficult feelings, periods of low mood and normal anxiety and sadness relating to common life events.

Helping young people manage normal changes of mood

When you are young these are hard to bear but there is a lot we can do to help children and young people manage these natural feelings before we give them a medical diagnosis of depression and anxiety.

Today there is an assumption that the mental wellbeing of the nation’s under-18s is worse than it ever has been. It is true there are many new pressures on them, maybe from social media, certainly from our education system, but 2017 data from the Office of National Statistics suggests that for England the increase over a 10+ year period was not actually that great.

What then has changed? In the 1980s I began my professional life as a secondary school teacher in a Bristol comprehensive. I can only think of one child who had any sort of mental health issue but many who had 'behavioural problems'! The impact of adverse childhood experiences on mental health was never mentioned. Now I realise that those children who were always in detention were struggling socially and emotionally. Today their teachers would be talking about their mental health needs and although sometimes help isn’t as available as we would like, thank goodness attitudes and understanding have changed.

Public health truth #2: our mental health is often outside our control

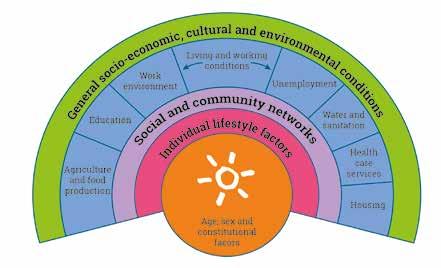

Students of public health will be familiar with the Dahlgren and Whitehead (1991) rainbow model of health determinants (see opposite). This acknowledges that our lifestyles affect our health and that there are strategies we can use that can radically improve or damage our wellbeing.

Being active, being outdoors, having hobbies, connecting with friends and helping others can all boost our spirits. Conversely, risky lifestyle choices can lead to low mood that may escalate into something more serious. But ultimately the model acknowledges that our health outcomes are fundamentally the result of things external to us.

As with our physical health, our genetic make-up, gender, age, ethnicity, our childhood experiences, education, relationships and community networks, our living and working conditions, income, local services and infrastructures, political decisions and social policy all play their part in how robust our mental health is throughout our lives.

Working with policy makers

Public mental health is concerned with this broad spectrum of determinants and so must work with a wide range of partners and policy makers, constantly prompting them to consider how what they do impacts upon the population’s mental health. For children and young people this means thinking about ante-natal care, early years experiences, what happens when they start school, how and where they play, how parents and carers are supported to nurture them, what our exam systems look like, how we support young adults into work and building strong and safe communities.

Public health truth #3: social inequality impacts our mental health

Our propensity to be healthy both physically and mentally is riddled with inequality. For sure money does not make you happy, but your postcode is a good indicator of your life expectancy, and economic hardship brings many hurdles that make maintaining your emotional equilibrium very hard indeed.

Just like adults, children and young people from all walks of life experience poor mental health but for those whose parents and carers experience social deprivation the challenges are immense, often overlooked and not championed.

Consider suicide rates amongst young people. Of course, the number of suicides amongst university students is a tragedy that hits the headlines and breaks our hearts but what of the even higher rate of death by suicide amongst young people who don’t go on to higher education? These continue to be less well reported.

A hill to climb

The Mental Health Foundation report (2020) 'Tackling social inequalities to reduce mental health problems' talks about a social gradient in mental health, stating “those who face the greatest disadvantages in life also face the greatest risks to their mental health”.

The Marmot Review ‘Fair Society, Healthy Lives’ (2020) highlighted such inequality, tracing its insidious impact from the point of conception onwards. As Mark Rowland, CEO of the Mental Health Foundation, comments: “Socially disadvantaged children and adolescents are two to three times more likely to develop mental health problems. We owe it to them to act, collectively and individually, to reduce social and economic inequalities and their mental health effects, so that everyone has an opportunity to have good mental health and to flourish.”

What is happening to children during the pandemic illustrates this well. It was brought home to me whilst walking my dog recently. I bumped into a fellow dog walker whose son’s year 9 group had been sent home to self-isolate due to a positive case in their bubble. The dad remarked how great it was as his son was getting almost one-to-one attention in the remote lessons as it was “unbelievable how many kids just did not bother to turn up to online classes’”. My blood pressure increased a little and I gently suggested it might be easier for some children to learn online than others.

Not everyone has the space, the equipment, or parents who are working at home and able to be supportive. This basic inequality not only impacts the young person now; the consequences of the increasing divide will be felt into the future.

Vicious circle

Finally, on the point of mental health inequality, it is important to note there is a ‘double whammy’ here, as the relationship between deprivation and mental wellbeing operates in two directions: being poor can bring about mental health problems, but mental health problems can also lead people into poverty due to discrimination in employment and reduced ability to work. How society tackles this and other social conundrums is the role of public health.

WE CAN ALL BE PUBLIC MENTAL HEALTH WORKERS

I started this piece saying that Covid-19 has increased the public’s awareness and understanding of public health. It has also highlighted the importance of public mental health. The Local Government Association report (2020) 'Public mental health and wellbeing and COVID-19' suggests the impact of the virus has been both immediate (for the duration of the epidemic) and is likely to continue longer term.

Children and young people may experience anxiety caused by concerns about the outbreak and possible illness, loneliness and friendship problems caused by self-isolation and social distancing, stress caused by adjusting to new routines and fears about the future. In the longer term they are also the generation who will be adults in the pandemic’s aftermath.

The consequences of this are likely to mean increased demand on local government and the NHS. The solution requires a whole systems approach with statutory services such as schools and health care, the voluntary and community sector coming together to provide neighbourhood action.

As you have got to end of this piece I am pretty confident this is something that matters to you. You too can be and probably are already a public mental health worker. You are an essential cog in the wheel for bringing about the change we need. You can do this through your work but equally through how you live your life and support the people dear to you. Keep going.

To conclude let me share a few lines from a poem I recently discovered:

Go to the Limits of Your Longing by Rainer Maria Rilke