19 minute read

Alaska Nellie

“There were possibilities of an extensive business at this place for at least three years, as I saw it, and now I would be needing a dog team and dog kennels, a place for harnesses and a small building in which to cook dog food. On the mountain above the lodge I cut logs for the kennels and the cookhouse." ~Nellie Neal Lawing in her autobiography, Alaska Nellie

Nellie Neal Lawing, Peerless Hostess for the Alaska Railroad

Advertisement

Alaska Nellie was one of the territory’s most colorful and beloved personalities, a largerthan-life adventuress whose exploits would easily fill a number of exciting books, beginning with her own autobiography. She was reportedly quite sweet-natured and ladylike, but she was also a hard-working, sharp-shooting, fearlessly independent entrepreneur who carved a place for herself at a time when that was a difficult challenge for anyone, let alone a diminutive woman with oversized dreams.

Nellie Trosper Neal, who would become familiar to Alaskans as “Alaska Nellie,” arrived in Seward on July 3, 1915, just as construction of the Alaska Railroad was getting underway. Nellie wrote in her autobiography, Alaska Nellie, that she set out to seek a contract “to run the eating houses on the southern end of the Alaska Railroad,” and she described her effort: “On my first time out on an Alaskan trail, I had walked one hundred fifty miles and as usual was alone. This accomplishment, in itself, might have satisfied some, but I was out here in this great new country to contribute something to others, and I felt this means could best be served by becoming the ‘Fred Harvey’ of the government railroad in Alaska.”

Likely due in part to her plucky approach, she was awarded a lucrative government contract to run a roadhouse at mile 44.9, a scenic location which she promptly named Grandview. Nellie was the first woman to be awarded such a contract. Her wage agreement with the Alaska Engineering Commission was to provide food and lodging for the government employees; her skill with a rifle filled out the menu, and her gifted storytelling kept her guests highly entertained. According to the terms of her contract, Nellie could purchase supplies from the government commissary, her freight would be delivered at no charge, and she would be paid fifty cents per meal and one dollar per night for lodging. The government employees on the railroad paid her with vouchers, which she turned in monthly for payment.

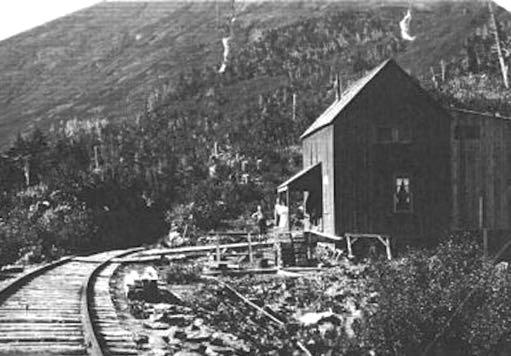

Alaska Nellie’s Grandview Roadhouse, Alaska Railroad mile 44.9, 1915

Nellie described the accommodations at Grandview in her book, Alaska Nellie: “The house was small but comfortable. A large room with thirteen bunks, used as sleeping quarters for the men, was just above the dining room. A small room above the kitchen served as my quarters. To the rear of the building a stream of clear, cold water flowed down from the mountain and was piped into the kitchen. Nature was surely in a lavish mood when she created the beauty of the surroundings of this place. The timber-clad mountains, the flower-dotted valley, the irresistible charm of the continuous stretches of mountains and valleys was something in which to revel.”

One harrowing event Nellie’s life occurred in the dark cold of winter. She generally used her dog team for trapping along the corridor which would later become the Seward Highway, but her team would play an important role in one of the major events in Nellie’s life. She tells the story in her autobiography, setting the stage with a description of a blizzard raging in the mountains, a mail carrier overdue, and the brief daylight passing:

Nellie at Grandview.

“A few hours of daylight was all we had and the Alaskan night settled down by 2 o’clock in the afternoon. The telephone rang and I was advised the mail had left Tunnel at 9 a.m. with a seven-mile journey by dog team to Grandview, the summit, and another five miles to Hunter. What a day to be on the trail! And still no sign of the mail carrier and five hours had passed since he left Tunnel.

“Five more hours went by and still no one arrived. During the next hour I decided to hitch up the dogs and go in search of the man, for I judged he must be in trouble.

“I left at 8 p.m., at the height of the storm, after putting a rabbit-skin robe, shovel, lantern and snowshoes on the sled. As I drove the dogs around the mountain where the howling north wind hit us, it was almost unbearable. The dogs refused to go and turned back to the sled. By putting on my snowshoes and breaking trail ahead of them, I urged them on and on.

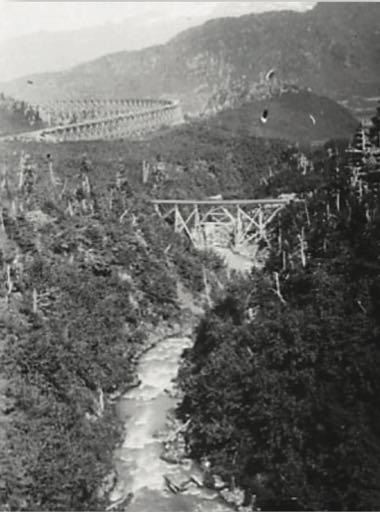

The railroad’s high trestle at mile 49. This is the area where Nellie rescued the dog team mail driver.

“As we entered Hell’s Acres, we encountered a large snowdrift covering the trail. After working our way over this, the dogs started on a run. They had scented the mail carrier’s dogs! They couldn’t be far away, but the blinding snow and darkness made it impossible to see but a short distance. After working our way over another drift, we came to the carrier’s dogs lying in the snow.

“Henry Collman, the carrier, was near the sled in a stooping position and nearing the point of becoming helpless, with his face, hands and feet frozen. His dogs were nearly exhausted. Hell’s Acres had him in its clutches and nearly claimed his life! I helped him on to my sled, but his dogs were not ready to go, as they were bedded down in the snow. At the approach of my dogs they growled and barked, but I was prepared to end their fight if they had attempted it. I put two of Henry’s dogs to my sled and turned the others loose to follow us.

“After arriving at the roadhouse I helped Harry into the house and began rounding up the loose dogs and tying them up. Back in the house, I found Harry in great pain. He was thawing out too rapidly. After filling a washtub with snow, I packed his feet with snow, then applied snow packs to his face and hands, keeping him warm at the same time so the snow would melt fast.

“He took hot drinks and I applied kerosene, which has a healing effect on frozen parts. After several hours be became drowsy and fell asleep. At 3 a.m. I hitched two of his dogs in with my team of five and went back for his sled and the mail. The wind ceased and the trail was covered with huge snowdrifts, but I made it through with snowshoes and the help of the noble dogs.

“I hitched the dogs to his sled and trailed my sled behind, working on the gee pole. When I returned to the house, my patient was still sleeping. I decide to take the mail through to Hunter, where they were holding the train for it, when I last heard from them. The wires had since gone down and there had been no news since early evening.

“The trail to Hunter was mostly down hill and was made without much difficulty, except for a few drifts. As I was driving up to the train, Lloyd Maitland, the conductor, said: ‘Here’s that damn mail carrier now! Say, dog musher, where have you been? What happened to you? We’ve been holding this train here all night!’

“‘Well, what a question to ask at a time like this!’ I said. ‘And besides, who do you think you’re talking to?’

“As I pulled back the hood of my parka, Maitland said:

“‘For the love of dog mushers! If it isn’t Nellie Neal! How did you happen to get the mail? We’ve been trying to get you on the ‘phone. I guess the wires are down.’

“‘I’m not guessing. I know they’re down,’ I replied. ‘Henry Collman, the carrier, didn’t get to Grandview, so I went after him and found him frozen down in Hell’s Acres. I took him to the roadhouse where he is now, and he was sleeping when I left. He was badly frozen.’

“The mail was put aboard and Mr. Maitland, the conductor on the train, gave me a receipt for the sacks and pouches, which I later learned contained valuable goods.

“It was 7 a.m. when I returned home. Henry was still sleeping. After putting the dogs in the kennels and making a fire in the kitchen range, I sat down to rest.

“When I attempted to get up, I staggered and nearly fell, but after breakfasting I felt better. I fed my patient and took food to the dogs. Henry’s first thought on waking was about the mail and his dogs.

“‘You have nothing to worry about,’ I said to him. ‘Your dogs are in the kennels and the mail is in Seward.’

“‘Well, tell me, how did it get there?’ he asked.

“‘If you must know, I took it. Here are the receipts for it that the conductor gave me.’

“Several days later, he and his dogs were taken to Anchorage where he entered the hospital and received treatment for frost bite. He fully recovered and left for his home in the ‘States.’

“Along this same trail where this young man came so near to losing his life, can be seen graves of several trail blazers who lost their lives at this point, where storms do their utmost to try the strength of man and beast. In the summer months a more beautiful place is hard to find. Acres of wild flowers cover the mountain slopes and valleys.

“Toward the end of the year, at the approach of the holiday season and my third Christmas in Alaska, a small package came through the mail, over the trail by dog team, for me. This contained one of the greatest surprises of my life. It was a necklace of solid gold nuggets! A large nugget formed the pendant in which a diamond was set. In the package was a note containing many names and these words:

To Nellie–from oldtimers Who on snowshoes broke down the trail; Who fought the elements to take through the mail. They struggled on without food or rest–To rescue the perishing they did their best.

Nellie proudly wears her gold nugget necklace.

Nellie tells another dog team story in her autobiography, Alaska Nellie:

“One cold winter day in December when the daylight was only a matter of minutes and the lamps were burning low, two U.S. marshals, Marshals Cavanaugh and Irwin, together with Jack Haley and Bob Griffiths, arrived at the roadhouse. The heavy wooden boxes they were removing from their sleds had been brought from the Iditarod mining district. They contained $750,000 in gold bullion. ‘Where do you want to put this, Nellie?’ called the men, carrying their precious burden.

“‘Right here under the dining room table is as good a place as any,’ I answered. And it was as simple as that. There it stayed until the men carried it back to the sleds, next day. They were able to go to sleep, for it was as safe right there in my dining room as it would have been in the United States Mint. No one would dare to touch it.”

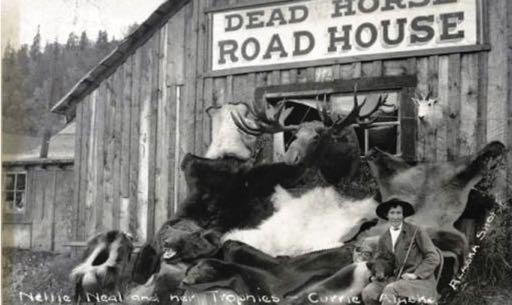

Over the years Nellie, known for her game hunting skills, built an impressive collection of trophies.

Alaska Nellie became known far and wide, and the foreword to a 2010 reprinting of her autobiographical book, Alaska Nellie, by Patricia A. Heim, sums up her legendary status:

“Nellie Neal Lawing was one of Alaska’s most charismatic, admired and famous pioneers. She was the first woman ever hired by the U.S. Government in Alaska. She was contracted to feed the hungry crews on the long awaited Alaska railroad connecting Seward to Anchorage. The conditions were harsh and supplies were limited. She delivered many of her meals by dogsled, fighting off moose attacks and hazards of the trail, often during below-zero blizzards. She always brought with her a great tale to tell of her adventures along the trail, how she had wrestled grizzlies, fought off wolves and moose, and caught the worlds largest salmon for their dinner, always in the old sourdough tradition. The workers listened and laughed with every bite.

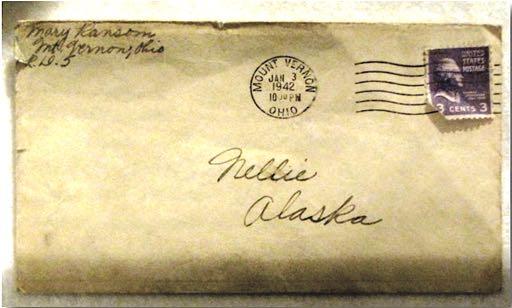

“Nellie was an excellent cook, big game hunter, river guide, trail blazer, gold miner, and a great story teller! It wasn’t long before Nellie became legendary and was known far and wide as the female ‘Davy Crockett’ of Alaska, her wilderness adventures and stories of survival on the trail spread like wildfire. Letters addressed simply ‘Nellie, Alaska’ were always delivered.”

Letters addressed simply ‘Nellie, Alaska’ were always delivered.

Leaving Grandview to operate the Kern Creek Roadhouse at mile 71 for a short time, Nellie then moved to the Dead Horse Roadhouse at a railroad construction site known as Camp 245, 22 miles north of Talkeetna. Almost at the halfway point between Seward and Fairbanks, on a level, well-timbered bench on the east bank of the broad Susitna River, Dead Horse Hill was the name first given to the remote camp, as it was said that in 1916 a team of horses was frightened by a bear and fell to their deaths from the top of a steep hill nearby.

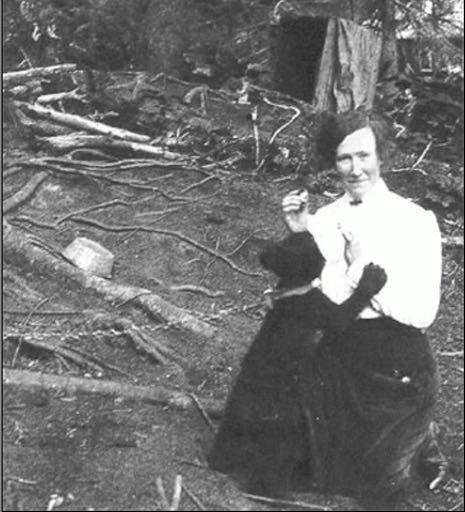

Nellie Neal and her pet bear at the Crow Creek mining camp near Girdwood, circa 1918. At the time Nellie ran the railroad roadhouse at Kern Creek, 71 miles north of Seward and five miles southeast of Girdwood.

Dead Horse Hill became the headquarters of the Talkeetna District and an important staging point for supplies and equipment on the northern half of the Alaska Railroad construction project, which included three important bridges: Susitna River, Hurricane Gulch, and the Tanana River at Nenana. Because Dead Horse Hill was such a key location, a large roadhouse was built at the site in 1917 to accommodate the construction workers, officials, and occasional visitors, and management of the new roadhouse was entrusted to the venerable Nellie Neal.

The Dead Horse Roadhouse, June, 1922.

Nellie took on running the Dead Horse Roadhouse with all the pluck and dedication she'd shown at Grandview, cooking meals on two large ranges for the dining room which seated 125 hungry workers at a time, and filling 60 lunch-buckets each night for the construction crews to take on their jobs the following day. In her autobiography she wrote, "I dished out as many as 12,000 to 14,000 meals per month, having two cooks, two waitresses and several yard men as help.”

In his pictorial history of the unique town which would later take the place of the government construction camp, titled Lavish Silence: A Pictorial Chronicle of Vanished Curry, Alaska, (Petersville, Alaska: Trapper Creek Museum Sluice Box Productions, 2003), author Kenneth Marsh described the roadhouse: "Nellie furnished meals to all employees of the Alaska Engineering Commission, who were building the railroad in the Talkeetna district, for fifty cents a meal. Sixty lunch buckets were filled every night. Sugar and flour was ordered by the ton. Meat came in whole animal carcasses. Her dining room seated one hundred and twenty five people at large, twenty-five person tables with benches. Nellie’s kitchen had two large ranges with hot water tanks attached. Thirty kerosene lamps lighted the dining room. All laundry was done by hand with washboards and washtubs. When a bath was requested the washtubs were moved from cabin to cabin and became bathtubs.”

And of the upstairs accommodations Marsh wrote: “...spring-less wooden bunks, straw mattresses and oil-drum wood-burning stove, all in one large room at the top of a flight of rickety stairs, held together by a warped wooden shell (which, at times, put up an uneven fight against the elements)."

With the completion of the railroad came significant changes to the little community, largely in the form of a luxury resort hotel built across the tracks from the roadhouse by the Alaskan Engineering Commission. In 1922 the name of the community was changed to Curry, to honor Congressman Charles F. Curry of California, chairman of the Committee on Territories, who was a strong supporter of the Alaska Railroad.

In his book Lavish Silence, Kenneth Marsh included an article from the December 2, 1922 issue of The Pathfinder of Alaska, newsletter of the Pioneers of Alaska, which described the impending demise of the Dead Horse Roadhouse: "The famous old roadhouse located at Mile 248 on the Government Railroad is now singing its Swan Song and will soon cease to function as a hostelry. The camp's name has also been changed to Curry–named in honor of Senator Curry, Alaska's friend. The Alaskan Engineering Commission now has a large railroad hotel nearing completion, which will be modern in every detail. Electricity, steam heat, hot and cold water systems are being installed, telephones, baths, laundry, big dining room and other conveniences all under the same roof as the depot, will ensure comfort to all guests. Old timers, however, will always think of the place as Dead Horse and in the same flash of memory will recall the days when Nellie Neal, the proprietor and domineering spirit of the place, reigned supreme."

Nellie at the Dead Horse Roadhouse, with some of her big game trophies.

In July, 1923, President Harding, his wife, and Secretary of State Herbert Hoover stayed at Curry on their way to the Golden Spike-driving ceremony at Nenana. The next morning Nellie served heaping plates of sourdough pancakes in her warm kitchen, commenting, "Presidents of the United States like to be comfortable when they eat, just like anyone else!"

Nellie retired from railroad service when the Alaskan Engineering Commission closed the Dead Horse Roadhouse at Curry in 1923. But from her days on the Seward end of the rail line, she remembered a lovely little log roadhouse near the beautiful blue-green waters of Kenai Lake, at a stop called Roosevelt. She had long admired the location, and when the roadhouse came up for sale in 1923 she purchased it and turned it into a museum for her multitude of big game trophies. Her collection already filled two railcars when she moved to the roadhouse, and it continued to expand while she lived there; among other prizes, it included three stuffed glacier bears.

In 1936, documentary maker James A. FitzPatrick produced and narrated a nine-minute travelogue film titled "Land of Alaska Nellie."

Nellie had been engaged to a friend named Kenneth Holden in 1923, but he was killed in a heavy equipment accident before they could marry. After she retired to the Roosevelt roadhouse on Kenai Lake she received a marriage proposal from Holden's cousin Bill Lawing; the two were married on the stage of Seward’s Liberty Theater on September 8, 1923. Nellie and Bill worked together to convert the Roosevelt roadhouse to a restaurant and museum. According to the 1975 National Register of Historic Places form, during Nellie’s lifetime the site included “about eight buildings, including greenhouse, garage, boathouse, museum, cafe/bar, four cabins, barn, and windmill. Probably the only structure dating before 1923 was the roadhouse, a one-story log building (about 20’ x 48’) with three large rooms: a trophy room, dining room, and kitchen.”

Nellie and Bill Lawing, at their home at Lawing, on Kenai Lake.

When a post office opened at the site in 1924, it was named Lawing in Nellie's honor, and she served as the postmistress for its first nine years of operation. Lawing became a popular tourist stop on the railroad and the highlight of any Alaskan visit. Her guest register of over 15,000 visitors over the next few years read like the Who’s Who of the early twentieth century: two U.S. Presidents, Will Rogers, the Prince of Bulgaria, authors, generals, politicians, celebrities, and many silent-screen movie stars. Nellie served her guests fresh vegetables from her garden and fresh fish from the lake, and the stories of her many adventures in Alaska kept her audiences thrilled, for here was a true Alaskan sourdough, a pioneer, a living legend.

Alaska Nellie became known far and wide, and in the foreword to a 2010 reprinting of her autobiography, Alaska Nellie, Patricia A. Heim sums up her legendary status: “Colt pistol on her hip and a baby black bear by her side, Nellie was always ready with one of her outrageous tales of adventure. ‘I was just minding my own business on Kenai Lake when a huge grizzly showed up, I fired my Colt, but as luck would have it, somehow, it misfired, I then had to kick the heck out of the brute and he ran off, but before he ran off he bit me good, right on the wrist, see here.’ She would then fold back her sleeve to show a scarred arm. Nellie was so popular and loved that she was honored in Anchorage with an ‘Alaska Nellie Day’ on January 21, 1956.”

Bill Lawing died of a heart attack in 1936. Heartbroken at losing him, Nellie continued entertaining guests and visitors for another twenty years, cementing her place in Alaska’s history by welcoming the humorist Will Rogers, General Simon Bolivar Buckner, and the actress Alice Calhoun into her home.

On May 10, 1956, Nellie died peacefully while sitting in her favorite rocking chair. She was buried next to her beloved husband Bill in the Seward cemetery, under magnificent huge Alaskan spruce trees. Her gravestone bears the image of a pineapple, a symbol of hospitality which began with the sea captains of New England, who sailed among the Caribbean Islands and returned bearing cargos of fruits, spices and rum.

According to tradition in the Caribbean, the pineapple symbolized hospitality, and sea captains learned they were welcome if a pineapple was placed by the entrance to a village. At home, the captain would impale a pineapple on a post near his home to signal friends he’d returned safely from the sea, and would receive visits.

Nellie’s happiest days were spent with the love of her life, Bill Lawing, in their log cabin on the shores of beautiful Kenai Lake. She mentions this in the opening paragraph of her autobiography:

“Glancing out through an open window of a large log home on the shores of Kenai Lake at Lawing, Alaska, the rippling waves had become glittering jewels in the full moonlight of a summer’s night. Mountains covered with evergreen trees and crowned with snow were reflected in the mirror-like water of Kenai Lake. Was I dreaming, or was the curtain of the past rolling up, so that I might glance back over twenty- four years spent in the great Northland and say, ‘No regrets.'”

Alaska Nellie on the porch of her wildlife museum at Lawing, on Kenai Lake.

In an article for Alaska Sportsman, published a year after Nellie's death, Carrie Ida Pierce wrote about a stay at Nellie’s roadhouse at Lawing: "That night I slept in a tiny room, in a huge bed that covered more than half the floor space," wrote Pierce. "On the wall was a lifesize oil painting of Alice Calhoun, an actress of silent movie days. A silk patchwork quilt was folded on the foot of the bed. Each piece of silk brought the memory of some tale. An old desk was crowded in a corner, and on it was the framework of cubbyholes that had been Lawing's post office when it had one, and Nellie was postmistress. Over the desk was a rack filled with loaded guns. It seemed I'd never get to bed. Nellie wanted to tell me the story of each thing in the room. A new and sympathetic listener was just the right person for Nellie to have around.” ~•~