The text pages of this publication have been printed on paper manufactured in Australia and produced from responsibly managed forests.

The text pages of this publication have been printed on paper manufactured in Australia and produced from responsibly managed forests.

As a professional body with individual members, the AIQS principal role is the development and promulgation of educational, behavioural and technical information and standards for the benefit of members and their clients.

So why does AIQS develop standards?

The simple answer is to establish appropriate professional benchmarks to assist members in the delivery of professional services to their clients.

The development and application of professional and technical standards provides guidance to AIQS members in relation to the delivery of professional

services (are aware of the risk issues in the delivery of a particular service) and informs clients and other stakeholders of those risks and the reasonable expectations from members (and nonmembers) in the delivery of those services.

Across the professional services sector there has, all too frequently, been a “raceto-the-bottom” in terms of fees in order to secure a contract. Unfortunately, this has invariably resulted in the provision of less than professional levels of service including, omissions, errors in reports, and potential negligence.

Over the past seven years, AIQS has received complaints against quantity surveyors in relation to breaches of AIQS’s Code of Conduct. These include complaints concerning deficiencies in the provision of tax depreciation reports, unprofessional conduct in the provision of progress valuation reports, not acting in an independent and impartial manner, major errors in calculating project construction costs, and overstating progress claims.

There have been several court cases over the years concerning duty of care, erroneous valuations, and negligent valuations. The outcomes of these court

cases highlight the necessity for quantity surveyors and other built environment cost professionals to check that they have adequate measures to manage their liability to financiers and developers. This should include appropriate quality assurance / quality control systems and processes, terms of engagement (including limitations on liability), and qualifications in respect of their valuations. As well as ensuring that they have appropriate insurances in place, quantity surveyors should keep a careful record of contributory negligence or failures to mitigate by other parties. While many companies will have in-

house systems with respect to how they deliver services to their clients, AIQS’s role is not to cut across those systems but provide impartial and expert information concerning a particular subject.

AIQS information papers are intended to reflect the most up-to-date information on a particular subject and are independent, expert, and impartial in nature (and at times may challenge traditional / existing approaches to the subject matter). They do not reflect the views of any one individual or company, rather they are designed to be transparent in nature, informative and educational. They provide information in such a way as to be equally informative to AIQS members and their clients. Should an information paper be interrogated with respect to its veracity it should be able to withstand such scrutiny in a court of law.

Professional standards establish benchmarks in relation to client engagement, the delivery of services by members, and increased awareness and benefits to members clients (including other end users of member services).

Clients of AIQS members and end users should also gain an appreciation of the level of service to be expected of quantity surveyors, at the same time understanding that the provision of high standards of quality professional services, comes at a price. That price reflects increased surety, reliance on standards, and level of professionalism in the service provided by the quantity surveyor.

Compliance with standards supports the professional standing of members as well as providing clients and end users with confidence in the quality of services being delivered. Standards also help members companies by:

1. reducing costs - through minimising errors, redundancies and increasing productivity.

2. efficiency - improving quality, safety, and lead-time of products and services.

3. mitigating risks - identifying and mitigating risks within their business and supply chain.

4. customer confidence - promoting acceptance of services into the marketplace by increasing customer confidence in their quality.

5. uniformity – providing uniformity of units of measurement, enabling accuracy and confidence in commercial transactions locally and globally.

In recent years, AIQS has been working with governments to provide guidance and explanatory information to members and the broader quantity surveying profession with respect to the application of regulations covering the delivery of built environment cost management services.

AIQS members with expertise on particular subject matters are encouraged to participate in the development of standards for the longterm benefit of the profession.

GRANT WARNER CEO Australian Institute of Quantity Surveyors

A key point I learnt during my studies was to pay close attention to detail in estimates and scheduling. It is easy to miss details hidden on the side of plans or in the specifications, and the absence of acknowledging could drastically change the outcome and accuracy of the work. Taking the time to check these details ultimately creates a more precise figure that could mean the difference between providing a weak or strong estimate.

Learning from mistakes and applying the corrections for future use is another great skill I learnt, as well as not being afraid to ask for help from my peers and tutors. This included attending extra tutorials, class discussions and acknowledging feedback on class exercises and assignment submissions. This translates into the industry as I find myself asking my work colleagues questions frequently, no matter how small or silly the question may be, allowing me to grow and improve on my knowledge and skills.

Finally, gaining exposure to the industry through organisations such as the NZIQS and Quantity Surveying Emerging Professionals (QSEP), has allowed me to network with working professionals and a variety of companies within the construction sector. I particularly found that attending events put on by the organisations offered great opportunity to be seen in a professional environment as well as learning valuable skills and information through conferences and presentations. In addition, networking through LinkedIn provided opportunities for making professional connections and keeping updated on potential jobs and career opportunities.

The most important things I learnt throughout my studies were the fundamentals of construction, measuring/estimation techniques and contract administration.

Gaining an understanding of building components and systems has given me the ability to interpret project documentation and determine construction methodologies and timeframes. Increasing my overall construction knowledge and understanding was essential in developing measuring and estimation skills.

Undertaking a wide range of measurement exercises resulted in being able to accurately produce schedule of quantities for a variety of trades and work packages. Experimenting with different methods of estimation for various projects and construction phases formed the basis of cost planning and management.

Learning about NZ construction contracts and understanding typical contract terminologies will enable me to better navigate and use construction contracts on projects throughout my career.

Achieving my Diploma in Construction (Quantity Surveying) has given me a solid foundation to start my career in the New Zealand construction industry. I’m confident that the many learnings and experiences I have gained from this time will be called upon as I head into the future.

During my degree at the University of Melbourne, I learnt how to work effectively in diverse teams, meeting goals, and embrace new experiences. The program attracted many enthusiastic students who enjoyed working on team projects and inter-university competitions. I had the chance to live at International House, where I made friends from around the world, and joined the mountaineering club, which allowed me to learn abseiling, camp in Central Australia, and challenge myself.

Moreover, I volunteered as the Partnership Manager at Robogals with Marita Cheng, Young Australian of the Year. Robogals is a worldwide organisation that aims to inspire and empower young women to consider studying engineering and related fields. I gained valuable skills in networking, and working with corporate sponsors to support Robogals' mission. Through the experiences, combined with my knowledge, I was enabled to develop a level of social skill, business acumen and cultural awareness. These skills have helped me build strong relationships and work collaboratively with clients and colleagues, and they have been invaluable in navigating the complexities of large projects. With a goal-oriented mindset, I perform to the highest standard and provide reliable cost management service, and I have had the chance to work on many significant projects in Australia, such as Metro Tunnel Stations, Westgate Tunnel, Queen Victoria Market, Royal Adelaide Hospital, Housing First and the Victorian School Building Authority as well as receiving scholarships to attend the PAQS Conferences and participated in the YQS program in Canada and Australia.

While working on the QVM asset register, I collaborated with other QS's and leveraged my skills to determine their strengths. I observed that one team member had excellent counting skills while I was more proficient in information management. As a result, we collaborated and played to each other's strengths to work more efficiently. This experience highlighted the importance of teamwork and communication and taught me how to identify and use individual strengths to achieve common goals. In conclusion, the team working skills and the strive for excellence I learnt in my QS studies have been highly relevant in my career and have provided the foundation I need to continue learning and growing in my field.

I came up through an engineering background, so AIQS Academy was the only formal QS education I receivedapart from learning on the job, of course. This helped me in many ways:

• It gave me a broad appreciation for what a QS can do, and what goes into doing it - definitely not exhaustive, but far more than you get in day to day work at even the best firms with the strongest grad programs.

• I had limited BQ experience at the time, and this gave me both an appreciation of the detail of what goes into it, and how. From memory, almost a third of the course is dedicated to BQ measurement methodology, and it's very important to do them consistently.

• Gave me a useful set of reference docs that I fire up every now and then.

AIQS Academy also took a lot less time than my university course - I completed the bulk over a 3 month period, while working full time and still having some form of life. There may be things I missed out on - a construction management degree means you'll meet a lot of your peers that you'll be working with for the rest of your career in construction - but I make do.

Other than the learning objectives that were provided to me prior to the commencement of my enrollment in the Construction management degree, the full extent of what I would experience and take away from the course was a little vague and somewhat missing worldly examples.

However, in looking back on my learning experiences, I conclude that much of the learning objectives undertaken have given me a thorough understanding and appreciation of the 4 following areas:

1. Cost Estimation and Management: the Quantity Surveying studies focussed on teaching the principles of cost estimation, cost planning, and cost control, which are essential skills in the construction industry. These skills have helped me to accurately estimate the cost of a construction project, manage costs, and identify cost-saving opportunities, which are all critical in the industry.

2. Project Management: Exposure to the construction management degree taught me the principles of project management, including project planning, scheduling, and monitoring. An ability to now be able to successfully manage time, cost, and quality to ensure that construction projects are completed on time, within budget, and to the required standards.

3. Contract Administration: I have obtained the relevant principles of contract administration, including contract law, contract drafting, and contract management. In parallel with also working for a PQS firm, I have been able to learn how to administer contracts, negotiate contracts, and

resolve disputes, which are all critical skills in the construction industry.

4. Communication Skills: As a Quantity Surveyor, you will need to communicate with various stakeholders, including clients, architects, engineers, and contractors. Quantity Surveying studies will help you develop strong communication skills, including the ability to communicate technical information to a non-technical audience. Good communication skills are essential in the construction industry to ensure that projects run smoothly and stakeholders are satisfied.

As I reflect on my journey through quantity surveying, there are a lot of essential skills and knowledge gained from my quantity surveying studies that have been invaluable in my career.

Some of the most important lessons I took away from my studies include a deep understanding of construction processes and materials. This has provided me the ability to understand work progress on site and determine if works are done as stated when assessing claims and variations.

Apart from that, the knowledge of building information modelling (BIM) during my quantity surveying studies have equipped me with the fundamental knowledge of this fast-evolving technology. I learnt to create BIM models, interpret complex models and navigate when working on BIM software. This has enabled me to navigate through BIM software, which has become the trend for quantity surveying.

Additionally, the cost estimation knowledge from my quantity surveying studies have built solid foundation for my estimation techniques. For instance, we learnt to use different functions in an estimation software and were taught various techniques in measurements. This allows me to work efficiently when it comes to measurement and pricing of an estimate. My proficiency in cost estimation is a valuable asset that continues to benefit my career.

Overall, my quantity surveying studies have provided me a wealth of theoretical knowledge and skills that I have been able to apply to real-world situations. This has helped me build confidence when navigating in the ever-evolving industry and succeed in the field.

Did you know that 100+ job titles sit within the quantity surveying profession? In this edition, we explore the numerous job titles and associated key responsibilities that are within the Utilities sector. In a future edition we will cover the Resources sector.

Electrical Estimator

An Electrical Engineer provides accurate cost estimates and cost advice for materials, subcontractors, and labour pricing. They liaise closely with suppliers, subcontractors and operational departments to determine accuracy of product pricing and availability, tenders and compliance. They also work to improve the estimating function by recommending and updating procedures and programs.

Senior Estimator

A Senior Estimator has proven estimating experience in utilities, projects or terms contracts with the flexibility to work on multiple bids across a range of disciplines within Utilities. Experience in Utilities sectors such as Water, Wastewater, Power Transmission Lines or Civil Structures, proprietary estimating packages and a strong commercial/numerical & analytical history. They usually undertake Take-offs and review Bill of Quantity / Drawings and utilize project management principles and scheduling. The also govern tendering, reviews and approvals.

Intermediate Estimator

Project Estimator

Civil Estimator

ToC (Target Outturn Cost) Development Manager

Contract Administrator

An Intermediate Estimator is responsible for reviewing contract documents such as scope of works, specifications, bill of quantities using first principle estimates and open market quotes from subcontractors and suppliers. They are also responsible for risk management, the management of tenders, evaluating subcontractor and supplier pricing, negotiating subcontract terms and conditions, and assist with the preparation of variation and EOTs.

A Project Estimator has experience in estimating HV and Gas infrastructure projects (Transmission Lines, Hydrogen, Desalination Water Projects).

A Civil Estimator provides leadership support to Estimating Lead and team members, undertakes detailed first principle estimating, obtains market coverage, and quantity take off, and provides support for cost loading of risk registers, program and forecasting. They coordinate with all stakeholders using estimating software with consideration of work break down structures, productivities and risk factors.

A ToC Development Manager leads the project/estimating teams on the strategy and construction methodology and builds a suitable program. They are responsible for coordinating overall bid development processes and managing compliance, pricing the tender and ToC submissions. They may also assist in the preparation of high-level cost plans, review of tender cost reports and pricing and scheduling, valuing risk and opportunities and maintaining relationships with owners, consultants, subcontractors, and suppliers.

A Contract Administrator prepares, manages and monitors contract securities, insurances, claims and variations under the head contract and key subcontracts. They support and coordinate the review and timely approval (or dispute) of payment claims, and overall lead the administration of subcontracts to support the project in achieving its cost, time and quality targets.

Cost Control Engineer

A Cost Control Engineer is responsible for the reporting, management, administration, and maintenance of project costs provided by the finance function. They also work with the project team to manage project risks, extract and analyse cost information and ensure schedule and cost phasing data are aligned.

If you feel that your job is related to the construction costs and isn’t listed here, we encourage you to let us know via marketing@aiqs.com.au

Will artificial intelligence and automation eliminate the need for quantity surveyors? I asked the world’s most advanced AI, ChatGPT, this question and the answer was emphatic.

“While AI can perform certain tasks quickly and accurately, it still lacks the human judgment and experience that is essential for making informed decisions. Quantity surveyors require not only technical knowledge, but also creativity, critical thinking and effective communication skills, which are difficult for AI to replicate.”

One paragraph is all it takes to dispel the myth that quantity surveying is limited to cost estimation or value engineering. Our profession is about problem solving – and that places us at the centre of project teams tackling the biggest problems of our time.

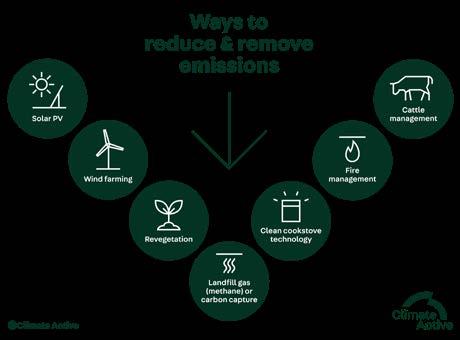

At Slattery, we are seeing this in our Carbon Planning Service, which we launched in 2021. Around a third of the average building’s total emissions are ‘locked in’ upfront, during early design phases, and we are increasingly working with developers, designers and builders to quantify those emissions. Our multidisciplinary team of quantity surveyors work alongside the design team to problem-solve and provide alternative design and specification options.

Similarly, our clients are looking to us to quantify their spend with Indigenousowned businesses and we are beginning

to embed this into our cost plans. We are also thinking deeply and widely about ways we can measure the value of Indigenous procurement to deliver the best outcomes for First Nations people with the help of our First Nations advisor, Yemurraki Egan.

These are just two examples of how the QS role is evolving into a trusted advisor that helps clients to solve problems and uncover new sources of value. And as every good quantity surveyor knows, as soon as we assign a value to something – whether environmental or social impact – it gets valued.

By Graham Topp MAIQS, CQS

By Graham Topp MAIQS, CQS

“The days of the court requiring parties in detailed commercial and construction cases to plead out everything to the nth degree are over. It is not sensible; it is not cost-effective; it is not proportionate. The parties, with the assistance of the court if they cannot agree, are duty bound to find a way of trying out the principal issues between them in a sensible and proportionate way.”

LJ in Standard Life Assurance Ltd v Gleeds (UK) [2022] EWHC 1310 TCC noteThis short article explores the ways in which sampling and extrapolation may arise. It also provides considerations for expert witnesses, and particularly those experts appointed to provide opinion on matters of quantum.

The proposition being that, absent a particular reason, if the findings of an appropriate sample are extrapolated, the outturn product is representative of the data set as a whole.

The first way in which sampling and extrapolation may arise is as a conscious choice. Where the testing of all evidence is plainly unmanageable and disproportionate to the value in dispute, the lawyers may plead from the outset that a sample and extrapolation methodology is required. A typical example is defect rectification. If 100 similar defects are claimed, the claimant’s lawyer may plead from the outset that the testing of 20 defects is a sample sufficient in size to obtain a decision from the court by extrapolation.

The second way in which sampling and extrapolation may arise is as a case management tool. This is where the court makes an order for trial by sample. Again, a typical example would be defect rectification. If 5,000 welding defects are claimed across a gas pipeline, the court may make an order for trial by sample.

The third and perhaps most frequent way sampling and extrapolation may arise is where the appointed expert proposes an appropriate approach to corral data sets. A helpful example may be the appointment of an expert to opine on the validity of costs incurred. Cost reports produced from modern business management software systems frequently run to several thousand transaction items.

Absent instructions from the court or the instructing lawyer, the expert should consider:

1. asking the instructing lawyer if a sampling and extrapolation approach is acceptable; and

2. if yes, select a representative sample in a pragmatic way.

The early meeting of experts is often beneficial. Assuming the party appointed experts are suitably experienced, early agreement as to sample size, sample type and other similar items can help narrow the difference in outturn opinions. For the quantity surveying expert, an early meeting of experts may even produce a ‘figures as figures’ valuation.

In instances where the expert is left to determine a representative sample, consideration should be given to the sampling method, sample size and presentation of findings.

In terms of the sampling method, the expert has a number of helpful tools at their disposal. The random array formula in Excel may be appropriate where each of the items in the data set are not dissimilar in type and value. For diverse data sets, monetary unit sampling is perhaps more appropriate. This is a statistical sampling method that is used to determine if costs or claims in a data set contain any issues or errors. When applied correctly, the monetary intervals provide a representative sample size and appropriate selection of items to be tested. Absent instructions from the appointing lawyer, it is perhaps best to avoid the ‘big ticket’ or ‘random’ method of sample selection. To my mind, these methods may invite challenge in cross examination. That is, a cross examiners assertion that items in the sample were ‘cherry picked’ in a manner that is favourable to the party paying the experts fees.

Once the chosen method is applied to the data set, it is perhaps an appropriate juncture to touch base with the instructing lawyer and discuss the sample size that is produced from the application of the chosen parameters. The instructing lawyer may have their own views as to the sample size produced and the extent to which it is representative of the data set as a whole.

A helpful starting point may be to apply a methodology that produces a sample which is greater than 50% of the data set as a whole. A sample of this size is preferred on the simple proposition that a conclusion is sought for the whole data set on the balance of probabilities. Depending on the objective, the sample may be determined based on either a value or numerical methodology.

Lastly, the expert should have regard to the construction and presentation of their analysis. A typical example of this is defect rectification where different types of defects are alleged. In this instance, the valuation ought to be constructed in a manner that enables a ‘pick and mix’ selection of defect categories, which are interlinked to items such as, for example, volume related preliminaries. This approach seeks to produce a valuation that permits the instructing lawyer to hypothesise valuation scenarios in the event it is decided that categories of alleged defects are not, in the court’s view, defective.

The correct approach to sampling and extrapolation is informed by the type, nature and value of the dispute. Please reach out if you would like to discuss this article, or any other quantity surveying principle.

For quantity surveyors, absent a particular reason, it is generally accepted practice that a sample size should be determined based on value.

If there is one thing that the past three years has taught us, it is to expect the unexpected.

Whilst there is very little that anyone can do to prevent pandemics and wars from breaking out, or earthquakes from occurring, we can at least do our best to protect what is ours by minimising the various business, market, legal and even governmental risks that could result in their reduction, diminution, or outright loss. Therefore, while we move forward with acquiring and accumulating our personal and business wealth; our empire, it is best to have a parallel asset protection process running in the background to ensure that we preserve and protect that wealth.

Asset protection often attracts a complicated mix of laws and regulations pertaining to companies and business structures, trusts and property, taxation, bankruptcy, and estate planning. Additionally, it often involves legally implementing a distinction between the legal ownership of the assets and the effective control and/or beneficial ownership of such assets.

Further, managing our wealth wisely usually includes consideration of the best way not only to preserve those assets depending on our individual financial circumstances and preferences but also the most efficient and cost-effective way to transfer or dispose of such assets to benefit others after our demise.

Of course, you need an advisor who is aware of the risks and claims which are common in the construction industry to properly plan the defences in extent and depth because otherwise, the taxefficient structure set up by an optimistic and friendly accountant will only mean that there is more for the creditors and other claimants.

Perhaps the first thing that comes to mind when it comes to asset protection is insurance, broadly covering property loss or damage and liability.

Beyond the insurance coverage required by law, there is a wide array of insurance policies available in the market. The advice of a trusted broker can certainly assist you to make a wise choice among these confusing choices, including helping you realistically identify and evaluate the risks you face. However, one has less protection under the Insurance Contracts of Australia, if you have a broker. This relieves the insurer of having to explain any unusual clauses.

It is obviously important to ensure that the appropriate type and level of cover is obtained depending on one’s circumstances and asset level, especially to avoid being over-insured and paying needless premiums or overlapping policies.

In any event, having the right amount of cover will go a long way to defray the costs of any damage or loss that you might sustain either in business or otherwise whilst holding an asset. One must always understand that the insurance company has a bi-polar condition. On the one hand, they have their friendly and charming premium collecting department; on the other hand, they have their aggressive and tightfisted claims department.

When one has endured and enjoyed the idea of having a substantial claim against you and indemnity denied, one has less confidence in insurance and more interest in protecting the empire.

There are several business structures that could be used with a view to protecting one’s assets and/or business.

Businesses could be run either by a sole trader, by a partnership, by a corporation, or by a trust. In the context of asset protection, the most common vehicles adopted are those of a corporation and of a trust.

This is because a sole trader does business in his or her personal capacity and therefore would be personally liable for the business’s debts or claims, leading to an unsatisfactory situation where the business’ creditors are able to recover payment against the sole trader’s personal property.

A partnership on the other hand involves the sharing of the management or control of the business and, being not a separate legal entity, generally renders all partners or any partner liable for the debts of the partnership. A partnership is generally, particularly in the construction industry, a highway to disaster.

In contrast to a sole trader or to a partnership, a corporation is a separate legal entity created under law and as such can hold property and assets separately from its shareholders, who are thereby shielded from the corporation’s debts and whose liability is limited to the amount due on their shares (although company directors may be held personally liable for company debts where certain director’s duties are breached or if the company commits insolvent trading).

Ease of transmission of ownership also exceeds that for sole trader or partnership businesses as each shareholder can transfer or dispose

of their shares quite effortlessly. A shareholder is usually protected from claims from creditors unless they are a de facto director.

Trusts are an established and very convenient way in which to protect assets in a form where they are fundamentally protected from your creditors if they have been set up appropriately and appropriate protection incorporated into the trust deed. However, the trust has to have a trustee who is trustworthy. One of the challenges in setting up a trust is to ensure that there is both a trustee who is trustworthy and also a reserve power in an appointor to appoint a different trustee if the first trustee is not performing in the way that one would expect the trustee of such a trust to perform.

Trusts have two basic structures. One is a discretionary trust where the trustee can allocate the income and capital among the beneficiaries; the other is a unit trust where the division of the income and capital is in proportion to the units held by each beneficiary.

A unit trust has to be used carefully in order not to put an asset in the hands of a beneficiary that might be attacked by creditors.

A unit trust has advantages in the sense that it might divide income, for example, proportionately among children or other beneficiaries, but has the problem that if the child is attacked by a disgruntled ex-spouse or a creditor, they may lose their unit entitlement. The best way to achieve family purposes is often to ensure that there is a combination of the

discretionary trust and the unit trust to achieve the desired purpose.

It is usually able to be attacked if an arrangement or trust is set up to avoid creditors. One must be careful to adopt appropriate stratagems with a view of protecting particular beneficiaries or family members rather than to avoid legal obligations.

If one has a spouse and one is committed to the spouse and the commitment is returned by the spouse and the commitment remains for the rest of the spouse’s lives, then it is a common strategy to have the assets held by the “non trading” spouse in order that they are immune from the attack of the potential claimant.

Of course, if the marriage breaks down, then the Family Court will have to decide on an apportionment of the assets among the two spouses and will generally take into account a fairly practical view of the relative needs and assets of each spouse.

Of course, spousal arrangements might be solid at the parental level, but one may have to plan with the view to blended families and protecting children who may go through the divorce many years hence, and accordingly, careful asset planning is involved.

Having acquired wealth, one is sensibly advised to ensure that one does have a Will that is consistent with your objectives and provides for efficient and effective means of protecting the transmission of the assets to those to whom you wish to direct it, whether that be your favourite child or the cats' home. Accordingly, one should have a current Will consistent with the assets that are

held and the direction in which they should travel, should you go to heaven early.

Without a clear and coherent plan to protect your assets in this life and to direct them appropriately while you're in the next life, a great deal of the effort and assistance that goes into acquiring an empire will be dissipated to the disadvantage not only of yourself but those who could look to you for assistance.

Accordingly, where in the construction industry, there are only the inevitables - death, taxes and risk, every constructorparticipant should have considered the options available and have the plan to continue to sophisticate their asset holdings as their assets grow.

Building with renewable engineered wood rather than concrete offers a significant win for the environment and the financials, a new case study has revealed.

The study used Clearwater Quays luxury apartments in Christchurch, New Zealand as a test case. Clearwater Quays was constructed as a part of Mid-Rise Wood Construction, a public-private partnership between the Ministry for Primary Industries and Red Stag Investments.

The aim of this $6.75 million programme is to encourage widespread adoption of precision engineered timber in mid-rise building construction. Since its inception in 2018, the programme has assembled a pool of New Zealand professionals experienced in mid-rise wood building design and construction to help share and grow knowledge and expertise with the broader industry.

‘Mid-Rise Wood Construction’ complements the government’s initiatives to encourage high value domestic processing and manufacturing from New Zealand’s plantation forests and deliver a zero-carbon construction sector by designing to increase low carbon materials used in construction. Programme projections suggest if engineered timber is widely adopted, this construction method could save the country $330m annually by 2036.

This extract focuses two sections of the case study:

1. Cost Management and Analysis of the project

2. Environmental Impact Analysis and CO2 Calculator.

“Calculations show that using wood in place of concrete to build this five-storey demonstration building is removing over a million kilograms of carbon dioxide from the environment,” says Barry Lynch,

MNZIQS, Reg QS, director of Logic Group, and Eoin McLoughlin, NZIQS (Affil), senior quantity surveyor for the Clearwater project.

Mr Lynch says carbon calculations for the Clearwater building show its timber construction saved 87,400kg of carbon dioxide (CO2), compared with a CO2 release of 952,600kg if it had been built of concrete, and 794,600kg if built of steel and concrete. The $3.37m price to design, develop and construct the apartment block would have been $3.89m for concrete construction or $3.59m for steel and concrete. The calculations include financial impacts of a reduced construction time.

The full Clearwater case study is now freely available for construction professionals (https://midrisewood. co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/ Clearwater-Case-Study-V2.4.pdf.). The full case study also includes general considerations, design, construction, and learnings.

The project has been deliberately designed to be open source, with all project information being made available to showcase the advantages of the new building materials and methods.

This case study uses a five-level, luxury, residential apartment building to highlight the holistic benefits of engineered- timber construction compared with a traditional steel and concrete approach.

The Clearwater Quays Apartments has a total floor area of 2,130 m2 (including garages) with two open-plan apartments per level overlooking the lakefront of the prestigious Clearwater development in Christchurch, New Zealand.

Combining cross-laminated timber (CLT), laminated veneer lumber (LVL), glulam and panelised framing timber (e.g., structural insulated panels) creates a cost-effective, fast, resilient, and sustainable system for mid-rise construction. Engineered timber is not only naturally beautiful but also provides a very strong, low carbon and comparably low-cost alternative to steel and concrete. It is easy to transport, relatively light, and has outstanding earthquake and fire resilience.

Cost comparisons for the Clearwater Quays project across three construction methods; concrete, steel, and masstimber, show that on a materials-only basis mass-timber had the highest cost. However, when the development impacts of the shorter construction programme were taken into account, the mass timber options became the least expensive by 6% compared to concrete and steel and 13% compared to the all-concrete option. In addition to the financial advantage of mass-timber builds, this case study shows environmental benefits that cannot be ignored. For the Clearwater Quays project, the carbon calculator for the mass-timber building was a net negative 87,500 kilograms. If the building were to be built in traditional steel and concrete, it would have resulted in 800,000 kilograms of carbon being released into the atmosphere, and over 950,000 kilograms of carbon if concrete alone had been used.

The Clearwater Quays project was commissioned by a company with an interest in the timber industry. Showcasing timber both structurally and visually was a driving factor of the design brief.

The challenge for Mid-Rise Wood Construction was to maximise

opportunities to highlight the aesthetic and structural quality of timber. This goal was achieved by incorporating dramatic, sculptural staircase structures projecting from the southern façade of each residential tower. These curvaceous forms create a counterpoint to the otherwise linear road- facing southern façade.

The spacious entrance lobby was designed to draw people into the building via a large portico structure. The apartment living areas face north with bedrooms and services areas orientated to the south.

The structural frame of each residential tower is entirely timber including CLT panel floors, and a lift featuring lightframed timber. The only non-timber elements to the structural system are the concrete slab ground floor, and footings.

The cost of a mass timber build compared to concrete and steel Mass-timber building using LVL, glulam and CLT is a relatively new method of construction. In the past decade, the building industry has seen an increase in interest, due to awareness of climate change and the need for sustainability leadership. This type of interest means that most mass-timber builds have been “passion” projects or statement buildings

that have been developed to show the possibilities as well as the direct and indirect benefits of this type of building. The construction of many bespoke masstimber buildings has involved a steep learning curve for the industry. Most buildings have been architecturally and structurally different and built to stand out as exemplar projects so extracting meaningful cost data from such projects can result in a wide range of information. Using such data can result in invalid comparisons with traditional construction methods, and many projects have defaulted to traditional builds due to this lack of validity.

More recently, the costs of mass-timber builds have been affected by increased industry experience, methodology developments, refined prefabrication techniques and greater competition among suppliers. These factors, combined with more accurate cost estimation software, better understanding of both programme savings and capital return durations, have resulted in more informed cost comparisons.

Increasing both the quality and type of information available to developers will continue to increase the uptake in masstimber builds

At the outset of this project, the quantity-surveying team built a ‘digital twin’ cost model for the Clearwater Quays development. (A digital twin in construction, engineering, and architecture is a dynamic, up-to-date replica of a physical asset or set of assets). The structural engineer developed alternative designs to sufficient detail for the construction manager to be able to estimate the build programme time and for the QS to be able to price the structure and foundations and estimate

Mass-timber construction is very much the hero of this project.

the cost implications of the time saving from constructing in mass timber. Building digital twin models for the structures was the next best option to constructing these on site. Within these models, design elements were incorporated that would be associated with these build methodologies.

For example, CLT floors would require acoustic cradle and batten flooring where concrete floors would not. Mass timber-builds would typically have lighter foundations than other methodologies.

The various approaches and considerations of structure, acoustics and fire across each design were addressed and incorporated into the cost estimates.

Utilising a building information modelling (BIM) / virtual design and construction (VDC) approach increases accuracy and allows cost findings to be communicated in a language that clients and design teams understand. All elements are

quickly interchangeable and can be fed back into build budgets. Back and forth discussions with the engineer refined these structures and increased the accuracy of cost estimation.

To fully understand any cost comparisons, there must also be a consideration of intangible inputs within the comparisons. Often such inputs are overlooked or there is simply not enough knowledge or expertise to inform feasibility investigations/comparisons. These are:

• reduced construction durations

• development cost - market risk

• development cost - carrying costs

• development cost - completion settlement.

Typically, the longer it takes to deliver the project, the higher the non-productive costs are. This is true for the construction programme but is also relevant to the developer’s capital investment and financing.

To put it simply, the longer it takes to complete the project the longer it will take the developer to return capital investment. It leads to longer finance carrying durations, increased risk, and can delay further opportunities to invest in the next project.

Utilising the above digital methodology has enabled a more robust and detailed cost estimation to be developed than could previously be completed without physically constructing each design.

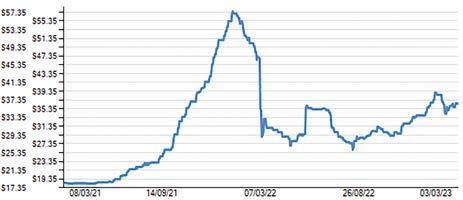

The results of these feasibility investigations are valid at the time of this case study (September 2021). Since September 2020 the cost of concrete and steel has increased relative to mass timber materials, improving the cost advantages of mass timber. The chart below contains typical cost-data comparisons for different types of construction materials.

Comparisons for the Clearwater Quays project across the three construction methods examined show that on a materials-only basis the mass timber had the highest cost. However, once Preliminary and General were factored in, all- concrete options were the most expensive.

When the development impacts of the shorter construction programme were taken into account, the mass timber options became the least expensive by 6% compared to concrete and steel and 13% compared to the all-concrete option. The development items are made up of the following being applied to each week saved or delayed:

• Market Risk – adverse property market move risk of 5%/year on a $18m value development

• Carrying cost impact – carry cost of $3m land, design/consent fees $2m and head office overheads $1m. Total $6m at 5%.

• Completion settlement/redeploy profit – Assume developer redeploys $2.7 (15%) profit in their next development worth $6.75m at 15% profit in the next year.

It is important to note that development costs will be subject to the developers’ own financing model, capital and

investment structure, and contractual exposure to market risk. The referenced figures are based on internal calculations for this project provided by Clearwater Development Ltd.

The length of time it takes to build a mass timber build compared to concrete and steel, and where savings can be made

Every project has different infrastructures and demands on programme deliverables. Preliminary and General items will usually include project costs that will not physically be left on site, e.g., professional supervision, site fencing, utility costs, insurance etc. On a typical medium sized contract of $10m, the

expectation would be for a $30,000 monthly average spend on preliminary and general.

For this project, the Clearwater Quay’s construction manager developed alternative delivery programmes for steel and concrete and full concrete structures and compared these with the known mass-timber programme. (It is worth noting here that the construction manager’s background and experience prior to this project had been in traditional building methods, and no allowance was made within the mass-timber programme for efficiencies associated with the learning curve required or lessons and skills attained).

The results of the comparison show that the mass-timber build had a programme saving of 2.5 months. These 2.5 months were saved during what would have been the critical frame-installation process where costs exceeded the average $30k spend and were closer to $70k. Theoretically, savings during this period would have been $175k when compared with an alternative build method.

Less time on site has many positive benefits in addition to the financial benefits discussed above. Using masstimber construction for the Clearwater Quays project has reduced disruption to neighbouring properties and generated interest that has resulted in positive engagement with the local community. Contractors working on site have noted the positive effects of a cleaner site and floors, reduced construction risk and an enclosed weathered environment earlier in the programme.

In summary, mass-timber builds can be cost effective when compared with other construction method but many factors need consideration to ensure comparisons are fair.

The most sustainable aspect of the building is the carbon sink of the building’s structure.

The living spaces are heated via reversecycle heat pumps, negating the need for a central heating system. Natural ventilation has been used for cooling in lieu of an artificial system and trickle vents were also introduced to provide make- up air (with acoustic baffles to control exterior noise).

Low-E glass was originally to be used just for the bay windows as these have the greatest potential for overheating, but following an upgrade from the glass supplier, all windows will now be double-glazed. Low E. Solar panels will supply the electricity demand to the majority of the common area (lobby and stairwell).

The Clearwater Quays project promotes environmental benefits in several different processes. These include:

Carbon

The processes of manufacturing building materials such as concrete and steel produce far more carbon than mass timber. In fact, there is more carbon already efficiently and safely stored within the timber material than produced during manufacture.

Mass timber is a carbon-negative material so using it results in carbon being extracted from the atmosphere and stored in the building material. That carbon storage can off-set the impact from other materials used in the building process, such as steel fixings, cladding systems, and foundations.

Lean construction and minimal waste is synonymous with off-site construction. The core structure of the Clearwater Quays Apartments can be categorised into three main elements: (1) CLT floors replace concrete and steel floors; (2) structural steel is replaced with LVL columns and beams to support these floors; and (3) there are the panelised / prefabricated timber frames. These components have all been manufactured off site in controlled manufacturing environments that utilise technology to control and minimise wastage, which substantially reduced onsite waste output.

The Clearwater Quays site was striving to be as close to zero-waste as practicable with all material being sorted before leaving the site. Materials that could be recycled were diverted to the correct facilities.

The use of a QS 3D BIM cost model added significant value in this area. The model not only replicated the construction build and every element, it also accurately quantified every piece of timber, every bolt and tape etc. The model contained information on material specifications, such as sheet sizes, timber supply lengths etc so was able to provide accurate order quantities by unit supply and could produce cutting lists for trades. This process provided key site performance information that encouraged efficient material ordering and use on site.

Most heavy traffic on site was generated from the movement of material. The biggest saving to time and cost of a mass-timber build is through the use of CLT floors, but this has other positive benefits too. Construction of a concrete suspended floor requires delivery and installation of several individual elements.

These include steel decks, timber formwork, steel reinforcing, and of course concrete. All this requires multiple truck deliveries arriving and moving on site. A typical CLT floor level at Clearwater Quays can be delivered to site and installed in less than one day.

As discussed above, alternative design methodologies were completed for concrete and steel construction. Using BIM 5D Cost modelling technology, the QS team explored various build options and demonstrated some significant findings regarding carbon footprints. The metadata now stored in the 3D geometry is typically used for cost calculation, but also contains embodied

carbon data. Carbon calculation is becoming a major consideration in building projects and can now be automated allowing for quicker and more flexible comparisons across build options. The results allow the client to understand the environmental impacts of their materials choices in conjunction with cost data allowing for more informed decision making. This system has been refined in house and automated for completing carbon calculation assessment at feasibility/ concept design stage. The models can be generated quickly by focusing on the variable core structures only, while the advanced parametric capability allows for quick conversion to the alternative material choice.

Live data feedback with referenceable 3D-model information allows for indepth analysis of different building and elemental options, which facilitates identifying and understanding the sweet spots between cost and carbon results in cost effective sustainable buildings. For the Clearwater Quays project, the carbon calculation for the masstimber building was net negative 87,500 kilograms. If the building were to be built in traditional steel and concrete, it would have resulted in 800,000 kilograms of carbon being released into the atmosphere, and over 950,000 kilograms of carbon if concrete alone had been used.

By Paul McArd MAIQS, CQS

By Paul McArd MAIQS, CQS

Following on from part one that was featured in the December edition of the Built Environment Economist, we consider four additional salient issues regarding common planning and programming issues:

• The project baseline and the level of detail

• Program updates and maintaining an as-built program

• Contemporaneous records and actualising: programs

• Delay allowances and contingencies.

All too often, baseline programs contain either too much or too little detail. An overly complex baseline can be challenging to manage and can quickly become irrelevant if it is not regularly updated. The level of detail must be proportional to the complexity of the project. However, subprograms or short-term programs should be developed, which relate directly to the baseline or “master” program.

contract deem that the tender program is the baseline program (AS2124) or is deemed a contract document, as is the case of AS4000.

Upon contract award, the contractor is usually required to submit a baseline or “contractors” program within a relatively short time frame (sometimes referred to as the “contract” or “construction” program). This updated program should capture more detail in the initial phases of the project, say the first six months, depending on its complexity and duration. Notwithstanding the contractual obligations regarding the program, the program can and should be updated to reflect future changes to the project’s delivery.

Depending on the contract requirements, the accepted baseline program should be updated with actual progress at intervals of no longer than one month (or more frequently on complex projects). The program operative should input the actual progress on a copy of the accepted program to create the periodically updated or “status” program by adding additional activities (“fragnets”) and updating the activity logic and durations to create a “live”, as-built program. The more often the program is updated, the easier this process will be.

to the program since the previous update (the accepted program). The purpose of saving periodic updates of the program is to provide good contemporaneous evidence of what happened on the project in case of a dispute.

The contractor must seek approval from the superintendent or employer’s representative with every update to the baseline program. Upon approval, the updated program will become the new contractor’s program. The superintendents view on progress should be reflected in the updated programs and disagreement resolved through the contract dispute resolution procedures.

“The CA’s view on progress should be reflected in the Updated Programs. The contractor’s position on the areas of disagreement should be recorded and submitted with the Updated Programs.”[1]

The as-built method of status updating has many advantages. As well as serving as the best method of delay analysis, it gives a clear presentation of planned against actual performance (a factual account of what happened, when and why).

The tender program is often used as the basis for the baseline program. It should be a fully logic linked network of activities that captures the true critical path and general delivery methodology, including the project key interfaces, deliverables, and constraints. In addition, one must consider the contractual obligations concerning the program. For example, some of the Australian standard forms of

Any delays to the planned works should also be incorporated into the updated program, including methodology changes and EOT events. Further program revisions should be created to assess potential (“what-if”) scenarios and their potential time impact analysed.

The updates should be saved electronically and archived. Each revision of the updated program should be accompanied by a BOS (basis of schedule) report that details any changes

It is systemic in construction project management that the program is only used to communicate “progress”, not the essential forecasting tool that it is supposed to be. This is primarily due to the way in which the program is updated. This may be in part to a lack of time or skill set. Typically, a perceived level of progress is determined by the program operative who is often

“All too often, baseline programs contain either too much or too little detail.”

SCL Delay and Disruption Protocol 2nd Edition: February 2017

divorced from the project. The operative may receive “status” information from the project team in relation to their perceived level of task completeness. However, more often than not, this perception is not reinforced with factual support and is incorrect.

The status of the works should be reinforced with evidence of progress, such as:

• photographs

• measured quantities correlating with progress claims

• marked up drawings

• drawing issue registers

• material delivery dockets.

The program operative should maintain an as-built program to maintain a historical critical path. “Actualising” activity start and finish dates or simply entering when the activity started and/or finished essentially removes historical logic, thus rendering the program useless in determining the historical critical path through the project. Similarly, relying on the software to determine the completion of an activity based on an interim perceived level of completeness often produces inaccurate forecasts.

works, whereas contingency constitutes a future event or circumstance which is possible but cannot be predicted with certainty.

Typical delay allowance considerations might include (contract dependent):

• inclement weather

• site IR disruption

• latent conditions (defined contractor risk events)

• resource availability and productivity

• changes to construction methodology or complexity not identified at contract award.

AS4300-1995 (unamended) allows for an extension of time to be claimed for inclement weather. However, most standard forms are amended to the effect that an inclement weather delay allowance should be pre-determined and incorporated into the date for Practical Completion (PC).

(a) The contractor acknowledges that the Approved Program allows for anticipated delays to the performance of the Works by reason of:

(i) inclement weather and the effects of inclement weather

A delay allowance should not be confused with “float” or contingency. A delay allowance represents a genuine assessment of potential delays and their probable impact to the progress of the

(ii) weekends, public holidays, rostered days off and other foreseeable breaks in the continuity of the works

(iii) subject to clause 35.5(d), any other delays that is reasonable having regard to the nature of the works.

The contractor is not entitled to any

extension of time for PC of the works if any delays to the progress of the works for any of the anticipated delays noted in this clause 35.5(a), all of which are and will remain at the contractor’s risk.

Recovery plans and strategies should be developed early on for high-risk activities to mitigate potential delays should they arise.

Such contingency strategies examples include:

• using air freight, not sea for long-leadtime materials from overseas

• working double shift work patterns

• working out of regular hours

• re-sequencing of works to overlap work fronts.

“The as-built method of status updating has many advantages.”

Early Contractor Involvement (ECI), in its broadest sense, can include any meaningful input provided by a contractor, prior to the commencement of the actual construction works.

Contemporary ECI tends to encompass a discrete pre-construction services stage, utilising the contractor’s expertise to procure better time, cost, and quality outcomes for the project. Ideally, this then flows on to a second stage, the formation of an agreement to undertake the actual building work.

Highly suitable for complex projects and new works to existing facilities, ECI has the potential to significantly de-risk a project. Design reviews that examine buildability, materials delivery, planning and value engineering, as well as more considered site investigations can help improve chances of project success. Other advantages can include the early provision of ancillary documentation such as environmental, safety, and management plans, and the opportunity to embed wider outcome requirements, together with local and cultural considerations. The nascent discipline of carbon accounting can also be initiated with the contractor, in conjunction with the wider supply chain. It is the contractor’s construction experience and relationship with the supply chain that can yield the greatest synergies, assuming these are deployed and managed in a timely and effective manner.

The ECI procurement model is currently a la mode, partly due to its efficacy in securing resources in a heated market. It can also provide synergies with contemporary initiatives that seek to engender higher levels of trust and partnering philosophies. It is advocated by the New Zealand Government Construction Procurement Guidelines for ‘large, complex or high-risk projects…

enabling robust risk management, innovation and public value’ . Topically, within the purview of the current revision of New Zealand’s pre-eminent construction contract, NZS3910, there is an initiative to define, in plain English, a framework for conducting ECI services.

The development of well-considered standard conditions of contract for ECI is timely and significant. There are currently few standard terms to define this growing procurement model. The UK’s Joint Contracts Tribunal and the collaboration-centric NEC4 contracts do provide options that cover such ‘preconstruction services’ but their suitability for application in current ECI initiatives in Australasia is limited. This leaves clients wishing to take advantage of the significant opportunities afforded by ECI to draft their own, bespoke provisions. This is not only wasteful but leaves parties to navigate and observe novel contract conditions when they could be concentrating on the ‘value-add’ activities noted above.

So, what should we be looking for in this process? What factors help increase our chances of success with this procurement model? Arguably, the foremost attributes are collaboration and commitment to the overall project. Client, consultant, and contractor teams that understand and can competently manage the process, working in a collaborative environment with successful delivery of the project at the forefront of all their endeavours, are much less likely to fail.

Timing of inception is also key. There is nearly always a trade-off between certainty of outcome and the opportunity

to influence. The optimum time for initiation of an ECI agreement is at concept design stage. With a reasonable outline of the project requirements, a high-level budget can be established, and a contractor proposal formulated which more easily offers a fixed allowance for on-site overheads as a starting point for an ECI bid. Much later than this, value management, buildability and design inputs tend to yield diminishing results and risk abortive work.

It is also absolutely critical that the scope of the ECI services is well defined. This would include confirmed deliverables and time obligations for all parties, as well as other salient performance criteria. All necessary deliverables and timing of information required should be clearly defined (yes, this is worth saying twice). The extent to which the contractor may be required to procure consents and the like (if applicable) should also be considered and agreed.

For the contractor’s part, they should be mindful of being held to the higher standard of ‘fitness for purpose’, rather than the lesser ‘reasonable skill and care’ usually applicable to consultant engagements. It is also important to consider how design liability may affect the wider supply chain where subcontractors and suppliers are providing design advice and alternative selections. This also applies to requirements relating to the use of intellectual property provided by any party. Matters of copyright and license,

¹ New Zealand Government Procurement (2019). Information Sheet: Early Contractor Involvement Construction Procurement Guidelines https:// www.procurement.govt.nz/assets/procurementproperty/documents/early-contractor-involvement-construction-procurement.pdf

“Any contractor design responsibility should be properly defined, understood, and insured.”

commonly addressed in consultancy contracts, are especially important where a subsequent build contract may, in some circumstances, be awarded to another party.

Other risks for contractors may include an expectation that the contractor, being more intimate with the project, will not seek further costs relating to deficient design or unexplored site conditions. Additionally, the ambit of ‘reasonably foreseeable’ may widen considerably because of the contractor’s deeper involvement in the pre-construction phase. To manage this, the contractor needs to thoroughly review the buildphase documentation, employing adequate design management skills to identify and adequately address any potential shortfall. This may be through revised documentation, agreed risk allocation, or the inclusion of contractorowned contingencies.

And for all this to work optimally, all parties need the requisite skills and attitude. The client’s team need to fully understand and drive the process and consider team delegations; the appointment of a lead consultant (often the client’s Architect) can provide a delegative authority (within the context of a collaborative partnership). The contractor should be able to provide the right people with the right aptitude. Selection of the team cannot be underestimated, and once engaged, they should not be removed without equal replacement (although this might be wishful thinking, given our current resource availability issues). Practical initiatives to encourage collaboration include facilities where teams can meet face-to face, focused workshops, and team building exercises. A prominently displayed project charter that records the agreed commitments of individual team members can also be effective.

It should be noted that the provision of pre-construction services does not sit within the traditional contracting economic model. Contractors often realise relatively low margins, based on high turnover and positive cashflows. Contractors’ staff engaged in ECI work are not focusing on their core, traditional construction duties. This raises the issue of proper remuneration for ECI services. Contractors have frequently offered such services free-of-charge, in exchange for the chance to procure work with better certainty. However, effective pre-construction services on large, complex projects requires consultancy-type skillsets, deployed for extended periods, incurring considerable expense. Adequate consideration (by way of payment) can also help define ownership of work to date should a subsequent build contract not be concluded.

Arguably the main disadvantage of the ECI model is lack of competitive tension in respect to the build contract price. Clients should consider engaging the services of a Quantity Surveyor, ideally to work closely alongside the contractor’s commercial team. As in other procurement models that utilise open-book pricing, confirmed benchmark rates and margins can form part of the contractor’s initial ECI bid, together with an agreement to seek multiple conforming tenders for subtrade work.

This should extend to other specific contract conditions for the build phase too; negotiating bond requirements and liquidated damages can become more awkward after the completion of the ECI phase. In our contemporary

market, agreed mechanisms to address fluctuations and super-normal price increases need to be pre-empted too.

If, for whatever reason, the construction contract cannot satisfactorily be concluded, consideration should be given to available action at that point. Indeed, the backstop of having a viable ‘out’ will undoubtedly assist in ensuring the parties stay focused on delivering value for money (although the philosophy of true collaborative spirit should, in theory, make this quite redundant!).

The risk of any implied obligation to proceed to a construction contract should be addressed in the terms of the ECI agreement. This may unavoidably extend to the wider supply chain, particularly with subcontractors and suppliers that provide input. The requirement to formally agree such matters at the outset extends to the continued use of intellectual property, and any ongoing design liability. Indeed, the relationship with the wider supply chain, both in a legal and societal sense, is a key risk (and opportunity) in the ECI model.

The successful conclusion of a beneficial ECI function on a complex project either requires an awful lot of luck, or a wellmanaged and competent team, engaged under a clearly defined and documented agreement. That agreement should confirm key deliverables, timeframes, and team members, with contractual provisions analogous to a suitable consultancy agreement. Hopefully, the hard work being undertaken in New Zealand by the team reviewing the NZS3910 form of contract will provide a useful basis for us all to conduct successful ECI projects in the future.

TOWARDS THE FUTURETRANSFORMATION, GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY

NZIQS invites our AIQS colleagues to join us at our 2023 conference in Hamilton from 7 – 9 June 2023.

A record 500 delegates attended the 2022 conference in Christchurch, the largest gathering of construction cost professionals in New Zealand. We have more topical and interesting speakers lined up for 2023 focused on the themes of transformation, growth and sustainability, as well as fun social events for team building.

The cost of achieving Greenstar

Economic updates

Legal presentations

Showcase of Hamilton projects

Carbon Accounting

Emerging Professionals mini conference

Motivational & Personal Development speakers

Communication workshop

Empowering women in construction panel

Workplace support – MATES in Construction

AIQS members can register at NZIQS member prices. Early bird registration closes 30 April 2023.

Wednesday 7 June 5.30 pm Welcome Drinks

Thursday 8 June Conference Plenary

Optional Social at Cosmopolitan Club

Friday 9 June Conference Plenary

Conference Dinner

See the 2023 Conference webpage for more information and how to register, or contact events@nziqs.co.nz

In Auckland New Zealand, about 40% of waste which goes to landfill comes from the construction and demolition (C&D) sector. This was about 570,000 tonnes of waste in 2019 (AKL Council)¹. Approximately 4% of this is plastic waste². Despite these large amounts of plastic waste coming from the C&D sector, there is a general lack of knowledge and focus around plastic C&D waste management.

In some other countries (e.g. UK, Germany, Sweden), there is a strong focus on reducing construction waste, which is closely connected to achieving carbon emission reductions. Europe is aiming for net zero carbon emissions by 2050, which is to be accomplished through the European Green Deal. As one of the adopted implementation strategies, a Construction Products Regulation is being proposed, whereby construction products must meet certain sustainability criteria. This includes giving preference to recyclable materials and designing products to facilitate reuse, re-manufacture and recycling, and producing instructions for repair of products. Additionally, the environmental information about the life cycle of products must be made available [3].

Although these legislative changes are not likely to impact New Zealand (NZ) immediately, this could pave the way for similar requirements to disclose key sustainability markers for construction products. This should provide an incentive for suppliers and manufacturers to work with the construction sector to improve product sustainability and could lead to lower waste production during construction. However, at the moment, construction waste reduction continues to be hindered by shortfalls in education and on-site practices, availability of

locally-based recyclers, coordinated and accessible waste transportation for reuse/recycling, and financial incentives. The following case study was undertaken to establish what could be achieved and if this model could be replicated further across the construction sector in Auckland.

A new residential build of eight terraced houses (six three-storey and two twostorey units) was constructed from August 2021 to September 2022, with the aim to divert 90% of its waste (Benton Ltd). Site staff (Windsor Construction) separated the different waste types into different bins/bulk bags. Plastic Waste generated from this site was separated into three categories (pipes, polystyrene and all other plastics), then audited by the Environmental Solutions Research Centre (ESRC). All remaining waste (e.g. timber, metals, cardboard) was audited and diverted by an external waste management company (Junk Run).

In order to prepare the site staff and subcontractors for the plastic waste sorting, ESRC delivered basic training and prepared a list of common construction plastics. All signage was provided with plenty of graphic support (e.g. pictures of waste types) and in collaboration with the site staff.

Once bags were full, the site owner delivered the plastics to recyclers (pipes to Marley, polypropylene to IP Plastics, ¹ Why construction waste matters. (n.d.). Make the Most of Waste. Retrieved February 3, 2023, from https://www.makethemostofwaste.co.nz/ construction-waste/why-construction-waste-matters/

² Ministry for the Environment. (2007). Targets in the New Zealand Waste Strategy: 2006 Review of progress (ME 802). https://environment.govt.nz/ publications/targets-in-the-new-zealand-waste-strategy-2006-review-of-progress/

³ European Commission. (2022). Q&A: Revision of the Construction Products Regulation. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/ presscorner/detail/en/QANDA_22_2121

“The as-built method of status updating has many advantages.”

polystyrene to Divert NZ, soft plastics to saveBOARD). All plastics (except for pipes and polystyrene) were delivered to ESRC for auditing, where they were weighed and analysed for polymer type (using FTIR spectrometry).

This trial conducted to gauge the cost of plastic was recycling on site, as well as to identify the different plastics coming from a construction site and their possible recycling endpoints.

The total cost of waste diversion on site, including waste management services for all waste types and transportation of waste to recyclers, was estimated to be NZD$16,400. The plastic waste management itself was estimated to cost NZD$600, which is very low compared with other waste. We estimate that the cost of hiring traditional skips for this site (for all waste going to landfill) would have been between $6,000-$10,000, which varies depending on the duration of hire and the mass/volume materials in the skip [a]. Therefore, the cost of waste management was significantly higher on this site than the traditional approach to send waste-filled skips to landfill. However, site staff expressed that they found on-site waste separation to be easier than anticipated. They thought that

while it did take more time and money than using a traditional skip, the results were worth it and they would recommend it to other sites. They were generally proud of what they achieved, despite it being more work.

Based on this study, the largest additional spend on waste management (for a 90% diversion) would be $10,000, which would be only a fraction of the profit made. This

amounts to 1% of the median Auckland house price ($1.1m in 2022) [e].

This residential 8-unit project was able to save 563 kg of mixed plastics, which is a carbon saving ranging between 2,300-3,900 kgCO2e (kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent) [b]. To put this into perspective, in 2021 there were 16,500 new residential homes built in Auckland [c]. Based on the same types

[a] Assuming a skip costs $300-400 (actually $360, based on Green Gorilla costs https://www.greengorilla.co.nz/services/ ). The min value is calculated using mass of total waste, max using volume of total waste.

[b] Based solely on the extraction and processing of raw materials, not including manufacturing or carbon used in recycling/transporting materials to recyclers (therefore: Cradle to gate system boundaries). Also – there is great variation in kg CO2e produced for different polymers, so the relevant minimum and maximum values were selected.

[c] Estimated from the number of homes consented in 2021, excluding apartments and retirement villages. https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/recordnumber-of-new-homes-consented-in-2021

“… Carbon savings would have equated to removing between 1,000 - 2,000 cars from Auckland’s roads in a year.”Image: Sign for new build residential site (40 Titirangi Rd, Benton Ltd) Image: Waste separation on site