WOOD ISSUE

Sylvan Industry

Carbon in the Forest

Forms of Mass Timber

2022 DESIGN AWARDS ISSUE

WINTER 2023

Johns Hopkins Surburban Hospital; Batlimore, MD www.polysonics.com 540.341.4988 ACOUSTICS • AUDIOVISUAL • IT • SECURITY • THEATER SYSTEMS

19107 215-569-3186, www.aiaphiladelphia.com.

The opinions expressed in this — or the representations made by advertisers, including copyrights and warranties, are not those of the editorial staff, publisher, AIA Philadelphia, or AIA Philadelphia’s Board of Directors. All rights reserved. Reproduction in part or whole without written permission is strictly prohibited.

Postmaster: send change of address to

IN THIS ISSUE , we look more closely at wood, perhaps the most common of building materials, to better understand the broad implications of its use.

FEATURES

12 Pennsylvania Forests and the Forest Products Industry

by Jonathan Geyer

by Jonathan Geyer

16 Carbon Markets in the Woods

by Calvin Norman

by Calvin Norman

20 Mass Timber Structural Form in Architecture

by Jim DeStefano

35 AIA 2022 Design Awards

Suggestions? Comments? Questions? Tell us what you think about the latest issue of CONTEXT magazine by emailing context@aiaphila.org. A member of the CONTEXT editorial committee will be sure to get back to you.

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 1

WINTER 2023

DEPARTMENTS 7 EDITORS’ LETTER 8 COMMUNITY 24 OPINION 26 EXPRESSION 28 DESIGN PROFILES

ON THE COVER

is published by

Photo: Tatiana Kuklina

CONTEXT

A Chapter of the American Institute of Architects 1218 Arch Street, Philadelphia, PA

Published JANUARY 2023 WOOD ISSUE Sylvan Industry Carbon in the Forest Forms of Mass Timber WINTER 2023 2022 DESIGN AWARDS ISSUE

AIA Philadelphia, 1218 Arch Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107

2022 BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Jeff Goldstein, FAIA, President

Rob Fleming, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, President-Elect

Robert Shuman, AIA, LEED AP, Treasurer

Soha St. Juste, AIA, Past President

Rich Vilabrera, Jr., Assoc. AIA, Secretary

Brian Smiley, AIA, CDT, LEED BD+C, Director of Sustainability + Preservation

Phil Burkett, AIA, WELL AP, LEED AP NCARB, Director of Firm Culture + Prosperity

Erick Oskey, AIA, Director of Technology + Innovation

Erin Roark, AIA, LEED AP, Director of Equity, Diversity + Inclusion

Fátima Olivieri - Martínez, AIA, Director of Design

Kevin Malawski, AIA, LEED AP, Director of Advocacy

Fauzia Sadiq Garcia, Director of Education

Timothy A. Kerner, AIA, LEED AP, Director of Professional Development

Danielle DiLeo Kim, AIA, Director of Strategic Engagement

Michael Johns, FAIA, NOMA, LEED AP, Director of Equitable Communities

Clarissa Kelsey, AIA, At-Large Director

Sophia Lee, AIA, NOMA, LEED AP B+C, At-Large Director

Scott Compton, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP, AIA PA Representative

Mike Penzel, Assoc. AIA, Director of Philadelphia Emerging Architects

Ross Silverman, Assoc. AIA, LEED Green Associate, SEED, Director of Philadelphia Emerging Architects

Tya Winn, NOMA, LEED Green Associate, SEED, Public Member

Kenneth Johnson, Esq., MCP, AIA, NOMA, PhilaNOMA Representative

Rebecca Johnson, Executive Director

CONTEXT EDITORIAL BOARD

CO-CHAIRS

Harris M. Steinberg, FAIA, Drexel University

Todd Woodward, AIA, SMP Architects

BOARD MEMBERS

David Brownlee, Ph.D., FSAH, University of Pennsylvania

Julie Bush, ASLA, Ground Reconsidered

Daryn Edwards, AIA, CICADA Architecture Planning

Clifton Fordham, RA, Temple University

Fauzia Sadiq Garcia, RA, Temple University

Timothy Kerner, AIA, Terra Studio

Milton Lau, AIA, BLT Architects

Jeff Pastva, AIA Scannapieco Development Corporation

Eli Storch, AIA, Looney Ricks Kiss

Franca Trubiano, PhD, University of Pennsylvania

David Zaiser, AIA, HDR STAFF

Rebecca Johnson, AIA Philadelphia Executive Director

Elizabeth Paul, Managing Editor

Jody Canford, Advertising Manager, jody@aiaphila.org

Anne Bigler, annebiglerdesign.com, Design Consultant

Laurie Churchman, Designlore, Art Director

2 WINTER 2023 | context | AIA Philadelphia

ARCH

Peter Martindell, CSI Architectural Representative 29 Mainland Rd • Harleysville, PA 19438 Phone: 267-500-2142 Fax: 215-256-6591 peter@archres-inc.com https://archres-inc.com Washroom Equipment Since 1908 Arch Resources Bobrick_NOVA 4/13/2021 10:58 AM Page 1

J Centrel/Shift Capital/JKRP

RESOURCES, LLC.

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 3 .COM EPSA . (215) 709 3245 . info-usa@epsa.com EPSA IS PROUD TO BE A SILVER SPONSOR OF THE R&D TAX CREDIT TAKE ADVANTAGE OF STREAMLINED PROCESS & COMMUNICATION OPTIMIZED CALCULATION & SUBSTANTIATION COMPLIMENTARY FEASIBILITY & EVALUATION HELPING ARCHITECTURE & ENGINEERING FIRMS

4 WINTER 2023 | context | AIA Philadelphia Proud to be a part of Anderson Hall providing consulting & supply of acoustical wood ceilings for 34 years www.ssresource.com Steve Schultheis (484) 885-9259/(800) 777-0220 Proud member of AIA, CSI, IIDA Your Single Source for Ceilings, Walls & Facades

Single Wythe Concrete Masonry is not only innovative, it’s also fire safe, affordable and beautiful. Visit our online Design Resource Center for the very latest in masonry design information - videos, BIM resources, design notes, and CAD and Revit® tools.

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 5 Celebrating Over 70 Years in Masonry Construction & Restoration 501 WASHINGTON STREET, STE 2 • CONSHOHOCKEN, PA 19428 (610) 940-9888 • www.danlepore.com DAN LEPORE & SONS COMPANY MASONRY AND STONE • ERECTION • RESTORATION • CONSULTING Rediscover the Many Benefits of Concrete Block. YOUR LOCAL CONCRETE PRODUCTS GROUP PRODUCER: resources.concreteproductsgroup.com

Since 1996 Parallel Edge has focused on providing Outsourced IT support for AEC firms and other companies specifically working with the built environment. Outsourced IT Services when IT is not what you do. 610.293.0101 www.paralleledge.com

TIMOTHY KERNER, AIA, Principal, Terra Studio and CONTEXT Editor

TODD WOODWARD, AIA, Principal, SMP Architects and CONTEXT Editor

TIMOTHY KERNER, AIA, Principal, Terra Studio and CONTEXT Editor

TODD WOODWARD, AIA, Principal, SMP Architects and CONTEXT Editor

THE TERRITORY OF WOOD

With this issue of CONTEXT, we take the opportunity to explore a single building material — a ubiquitous substance that is familiar to us all. Craftspeople, carpenters, designers, and artists develop, highlight, and exploit the characteristics of wood in works of all scales. Wood is incredibly versatile: It can be a structural material or a finish material, and it can be a design element ranging in size from picture frames to high rises. The use of wood has implications for design and craft, for climate and the environment, and for building our communities.

Wood is a conventional building material, embedded in the history of design, construction, and shelter within many traditions. It is also a newly appreciated material for its wide-ranging environmental implications. In this issue, we share a few voices and perspectives on wood and present innovative examples of its use in architectural design.

The articles begin with an essay on the forests of Pennsylvania and their essential role in the natural environment and as a source of construction material. The element of carbon is then considered as it relates to the growth and harvesting of trees, climate change, and the nascent attempts to link these aspects through carbon markets. The third feature article looks at the old but new technology of mass timber construction and its potential to unite architectural expression with structural form.

The Expression section features a photo essay on raising a traditionally framed gazebo, and the Opinion piece offers wise counsel on building responsibly with wood and the importance of a thorough understanding of the nature of the material and the characteristics of the land where it grew. The innovative use of wood is the focus of projects in the Design Profiles section. As a finale, we proudly present the 2022 AIA Philadelphia Design Awards. Wood was not part of the criteria for the awards but, not surprisingly, it plays an important role in many of these excellent projects.

CONTEXT invites you to revisit your relationship with wood and consider its enormous design potential. We hope this issue contributes to an increased understanding of the various facets of this important natural resource and leads to further investigations of your own.

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 7

EDITORS’ LETTER

Dear Friends and Colleagues, Welcome to 2023. Congrats to Todd Woodward, AIA and Tim Kerner, AIA for this issue of CONTEXT. It is thoughtful and provides a broader frame of reference for the use of wood in design and construction. This is what makes our magazine such an important part of the content that AIA Philadelphia produces each year — our magazine provides an opportunity to stop and think a bit more deeply about a topic than our busy, overscheduled lives allow. Thanks to Todd and Tim for their contributions to this issue and to CONTEXT in general.

Congratulations to the 2022 Design Awards Project Winners featured in this issue. Every year we pick an out-of-town jury to deliberate and select our winners. And every year they face an incredibly difficult task because the quality of work produced by our local architecture firms is simply exceptional.

Congratulations to all the teams who submitted work in 2022 — we look forward to highlighting your work throughout 2023.

As we start 2023, AIA Philadelphia is continuing to evaluate how we provide value to our members. Just like everyone else, we are trying to thread the “in-person/hybrid/virtual” needle to strike the right balance for our members and our community. We know people want to gather — but how much? We know some committees’ engagement has skyrocketed because of the ease of virtual programming — how can we spread that engagement to more of our committees? If you see a post on social media or receive a request to come meet with your firm to share feedback — please take the time to share your thoughts with us so we can help you get the most out of your membership.

One of the issues we will be keeping a close eye on is our monthly Architectural Billings Index (ABI) from AIA National.

Billings at architecture firms softened considerably in October with an ABI score of 47.7, as firms reported the first decline in billings since January 2021. Economic headwinds have been mounting, and finally led to weakening demand for new projects. While one month of weak business conditions is not enough to indicate an emerging trend, it is worth keeping a close eye on firm billings in the coming months.”

— www.aia.org ABI, October 2022

In the event that architectural billings continue to soften, AIA Philadelphia will respond with resources and support for our member firms.

Our next issue of CONTEXT is focused on the BUILDPhilly Coalition’s Mayoral Forum, date to be announced soon, in March 2023. I hope that you will attend and share your thoughts for what the AIA Philadelphia community wants to see from our next Mayor.

Enjoy your winter season and hope your friends, family, and colleagues stay healthy and prosperous!

Cheers, Rebecca

2023 AIA Philadelphia Board Induction

Join the Philadelphia architecture community for the first event of the new year and welcome the newly elected board of directors. Currently planned as an in-person event on January 12, 2023 from 5:30-7:30 PM at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia. To register, please visit aiaphiladelphia.org. Cost is free to attend.

8 WINTER 2023 | context | AIA Philadelphia COMMUNITY PHOTO: JULIA BLAUKOPF

WELCOME 2023 AIA BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Congratulations to the 2023 AIA Philadelphia Board of Directors. This year’s board features three new members and a number of current Directors elected for a second term. If you are interested in

President — Rob Fleming, AIA, LEED AP, BD+C, Director of Education, Jefferson University

President-Elect — Brian Smiley, AIA, CDT, LEED BD+C, Senior Project Architect and Director of Sustainability, HOK

Treasurer — Robert Shuman, AIA, LEED AP, MGA Partners and Associate Professor and Program Head of Architecture, Temple University Tyler School of Art and Architecture

Secretary — Fátima OlivieriMartínez, AIA Principal, KieranTimberlake,

Past President — Jeff Goldstein, FAIA Principal, DIGSAU

Director of Sustainability + Preservation — David Hincher National Director of Sustainability, NELSON Worldwide

Director of Firm Culture + Prosperity — Phil Burkett, AIA, WELL AP, LEED AP, NCARB

Principal, Meyer Design

Director of Technology + Innovation — Eric Oskey, AIA, Technical Director Moto DesignShop

Director of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion — Erin Roark, AIA, LEED AP Senior Associate, WRT

Director of Advocacy — Kevin Malawski, AIA LEED AP Founder and Principal, Karbon Architects

Director of Equitable Communities — Michael Johns, FAIA, NOMA, LEED AP Principal, M Designs + MWJ Consulting, LLC

Director of Education —

Fauzia Sadiq Garcia

Principal, Sadiq Garcia Design

Director of Design —

Ximena Valle, AIA, LEED AP Founding Principal, FIFTEEN

becoming a board member, reach out to any current board member or keep an eye on your inbox in late summer for the annual call for board nominations.

Director of Professional Development —

Timothy Kerner, AIA Principal, Terra Studio, LLC.

Director of Strategic Engagement —

Danielle DiLeo Kim, AIA Executive Director, Philadelphia 250

Director of Philadelphia Emerging Architects — Michael Penzel, Assoc. AIA Gensler

Director of Philadelphia Emerging Architects — Luka Lakuriqi, Assoc. AIA, SEED Independent Designer

Director At-Large — Clarissa Kelsey, AIA Associate, Stantec

Director At-Large — Sophia Lee, AIA, NOMA, LEED AP BD+C Project Architect, Jacobs

AIA PA Representative — Scott Compton, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP Principal, Compton Associates

Director of Equity, Diversity, + Inclusion and Public Member —

Tya Winn, NOMA, LEED Green Associate, SEED Executive Director, Community Design Collaborative

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 9 COMMUNITY

The 2022 DesignPhiladelphia festival kicked off on October 12 at Cherry Street Pier and, over the course of 12 days, saw 117 events take place throughout the city. Highlights included the Design is Inclusive exhibition featuring textile designers of varied backgrounds with strong Philadelphia connections both past and present, the Emerging Designer Showcase highlighting new designers redefining the Philadelphia design landscape, Designing a Learning City exhibit exploring projects led by the Playful Learning Landscapes Action Network, and the return of the weekend-long Kids Fest with two days of activities for kids of all ages.

Visit designphiladelphia.org to view the gallery of photos and a complete wrap report of the 2022 festival. And don’t forget to mark your calendars for the first DesignPhilly event of 2023, a joint event with Creative Mornings on February 24, 2022.

10 WINTER 2023 | context | AIA Philadelphia COMMUNITY

PHOTOS: CHRIS KENDIG

PHOTO: TIFFANY MERCER ROBBINS

According to a new EdSurge article titled “Learning Pathways for District-Wide Integration of Skills for Innovation,” we are living in the “Fourth Industrial Revolution.” Students will now need more than mathematics and language arts skills to succeed in the career of their choice. Any path a student may take, from technology takeovers to a rise in socialemotional knowledge, will require them to prioritize their innovation skills, creative thinking, and social-emotional learning strategies. So what does this mean for the typical curriculum in today’s classrooms? K-12 classes of the future will need to change how students learn to encompass a more hands-on, creative approach.

The Center for Architecture and Design’s Architecture and Design Education program integrates alternative learning methods into K-12 classrooms throughout the School District of Philadelphia. Architects, engineers, and designers from all backgrounds volunteer their time and professional expertise to expose students to architecture and design through hands-on learning opportunities that promote design thinking. The curriculum is structured to build students’ confidence and teach them to think outside the box, collaborate with other students, and present their creations to an audience.

ADE program observers see a direct correlation with students who have had to persevere through a challenging lesson often having a positive experience with the program. As ADE continues to blaze forward, we look forward to sharing other positive outcomes we can attribute to this new style of learning.

17 COMMUNITY

PHOTOS: SCOTT SPITZER PHOTOGRAPHY

PENNSYLVANIA FORESTS AND THE FOREST PRODUCTS

12 WINTER 2023 | context | AIA Philadelphia

Rider Park in Trout Run, Pennsylvania.

INDUSTRY

BY JONATHAN GEYER

Pennsylvania is the only state named for its forest. William Penn founded his colony in 1681 and its name paid homage to his father, Admiral Sir William Penn, and the vast forests that characterized the area — Sylvania is Latin for “forest land.” The forest and forest products industry have a strong connection not only to the state, but to Philadelphia, where Pennsylvania’s first sawmill was located. One of Penn’s early ordinances for the colony required that settlers leave one acre of trees intact for every five acres cleared,1 which would result in the state being at least onesixth, or 16.7% forested.

Throughout Pennsylvania’s history, our forest was a primary resource used to build and expand the nation. When Penn arrived, the forests were dominated by two species — white pine and eastern hemlock — which were heavily used by the colonists. White pines, due to being extremely tall and straight, were used for ship masts, and Eastern hemlocks for their bark, which contains tannic acid used for tanning leather. Forests were also cleared for crops and livestock, and to provide wood for homes, fences, rail ties, heat, and charcoal production for smelting iron. By 1900, the pace of industrial production and clear cutting of the forests had left most of Pennsylvania barren, leading to what many have referred to as an ecological disaster.

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 13

PHOTO: COURTESY OF KEYSTONE WOOD PRODUCTS ASSOCIATION

PENNSYLVANIA FOREST INVENTORY

Thanks to a handful of key figures, Pennsylvania was placed back on track to once again be the Sylvania for which it was named. These figures include Dr. Joseph Rothrock, the father of Pennsylvania forestry; Mira Lloyd Dock, a leader in city beautification and first woman named to the Forestry Commission; Gifford Pinchot, the first head of the US Forest service and twice governor of Pennsylvania; and Maurice Goddard, a pioneering forestry educator and leader in creating many of Pennsylvania’s state parks, as well as others with less recognized names. If William Penn were to visit today, he would find a Penn’s Woods that exceeds his original goal by three and a half times, with hardwood forest covering nearly 60% of the state — the nation’s largest hardwood forest — restored and flourishing due to the visionary, progressive action of these leaders.

HARDWOOD AND SOFTWOOD

There are over one hundred species of tree that grow in Pennsylvania’s forests that are tracked by the US Forest Service Forest Inventory and Analysis program. However, just 16 species or species groups make up 93% of the forest. Some of the most valuable lumber species include oaks, maples, cherry, poplar, ash, and black walnut. Because white oak and chestnut oak are both sold as white oak, they are grouped together in FIGURE 1. Various species of red oaks and hickories are also grouped together.

The quality of Pennsylvania’s hardwood lumber is sought throughout the world, especially by furniture manufacturers. Our northern climate and shorter growing season, tighter growth rings, soil composition, and mountainous elevations mean Pennsylvania lumber tends to be more stable and less likely to warp and twist after being properly dried. Pennsylvania is widely known as the “Black Cherry Capital of the World.” Black cherry has historically been one of the more valuable hardwood species and nearly 30% of the nation’s black cherry volume is in Pennsylvania.

About 90% of Pennsylvania’s forest is hardwood and 10% is softwood. Hardwood is another term for deciduous trees, FIGURE 2 These trees have broad, flat leaves and their seeds come from flowers. Examples include white & red oak, sugar & red maple, and hickory. The durability, strength, color, and grain of hardwood lumber make it preferred for flooring, furniture, and cabinetry. Softwood is another term for coniferous trees, which have needles that generally stay green year-round, and their seeds come from cones. Coniferous trees are used in North America for construction grade timber (Spruce Pine Fir, or SPF Framing Lumber). Houses are built with softwood lumber, then furnished with hardwood lumber.

FOREST PRODUCTS INDUSTRY

Many Pennsylvanians do not realize that we have much more forest today than we had a hundred years ago. Each year our forests grow on average between three and four billion board feet. We lose about one billion board feet per year to natural mortality (old age, invasive insects, disease, etc.) and the industry harvests about one billion board feet. Harvesting occurs throughout the state, and our forest volume is increasing by roughly two billion board feet every year, demonstrating the sustainability of the industry’s management methods.

Today, there are 16.6 million acres of forested land in Pennsylvania. This equates to 121.6 billion board feet of sawtimber. Sawtimber is defined as trees with a diameter at breast height (DBH) of greater than eleven inches. Since 1955, the sawtimber volume in Pennsylvania has increased by more than five times, FIGURE 3 Pennsylvania not only leads the nation in the volume of hardwood forest, but also in the volume of hardwood lumber created and exported. The forest products industry has over 2,100 companies that employ more than 60,000 Pennsylvanians, and the industry has an annual direct impact of $21.8 billion on the state’s economy.2 Sustainable forest management is a top priority of the forest products industry. Forests are similar to crops; however, unlike corn or soybeans that have short rotations, forests grow and require management over a longer time period. Like farming, forest management involves weeding and thinning to increase yield. Trees compete for water, nutrients, light, and space. Proper forest management is designed to weed and thin the

14 WINTER 2023 | context | AIA Philadelphia

forest to establish the next crop.

RANK SPECIES PERCENT OF FOREST 1 Soft Maple 15.4% 2 Northern Red Oak 13.0% 3 Black Cherry 11.4% 4 White Oak 11.2% & Chestnut Oak 5 Hard Maple 7.4% 6 Yellow Poplar 6.9% 7 Eastern Hemlock 4.9% 8 Other Red Oaks 4.9% (Scarlet & Black) 9 Eastern White Pine 3.8% 10 White Ash 3.6% 11 Sweet Birch 2.8% 12 Hickory 2.8% 13 American Beech 2.3% 14 American Basswood 1.4% 15 Bigtooth Aspen 1.0% 16 Black Walnut 0.7% Other Hardwoods 4.7% Other Softwoods 1.8% Total Hardwoods 89.5% Total Softwoods 10.5%

FIGURE 1 Make up of Pennsylvania’s forest based off 2019 US Forest Service Forest Inventory Data. Percentages determined by comparing overall species volumes.

FIGURE 2 Geographic distribution of hardwood and softwood across the state. Data provided by the National Atlas of the USA.

SOFTWOOD HARDWOOD OPEN WATER NONFOREST

In Pennsylvania, it is seldom necessary to plant following a timber harvest, as most forests naturally regenerate. In a mature forest, which much of Pennsylvania is, the forest’s leafy canopy is so thick that the sunlight does not reach the forest floor and seedlings cannot grow, so by harvesting we are allowing new growth. The industry takes pride in knowing that when a tree is cut, all parts are used: veneer logs for valuable veneers; saw logs to grade lumber for furniture, cabinets, and flooring; low grade lumber for pallets; small logs to pulp for paper products; sawdust for pellets; and bark for mulch. There is zero waste.

Pennsylvania’s forest products industry harvests between one billion and 1.3 billion board feet of forest volume annually. To put that into perspective, one board foot is a piece of lumber 12 inches wide by 12 inches long and one-inch thick. One billion board feet equates a stack of lumber 2.5-feet high by 5-feet wide, spanning from Harrisburg to Houston, Texas — 1,228 miles!

FOREST OWNERSHIP

Compared to states that have large tracts of National Parks or National Forests, Pennsylvania has a balance of ownership between government and private forest landowners. The federal government owns 3.94% of the forest land in Pennsylvania, mainly in the Allegheny National Forest. Additional acres of forest are owned by the National Park Service, US Fish and Wildlife and the US Department of Defense. Pennsylvania state government has three major land-owning agencies that together own 23.3% of the forest. While the acres are not all forested land, the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, or DCNR, Bureau of Forestry manages 2.2 million acres, DCNR Bureau of State Parks manages 300,000 acres, and another 1.5 million acres make up Pennsylvania Game Commission public game lands. Local governments own an additional 3.5% of the forest for local parks and watershed protection

This balance of ownership between government (30.8%) and private (69.2%) is critical for the state’s forest products industry. Government-owned forest land typically needs to reach annual harvesting goals to meet important objectives such as forest health and ageclass distribution. This means that forest management practices continue to occur even when markets are unfavorable, that is when prices are low, so private forest landowners are not selling timber. This sustained supply of raw material into the forest products industry is crucial.

The 69.2% of privately owned Pennsylvania’s forest includes 2.3 million acres owned by corporations, including timber investment management organizations (TIMOs), 559,793 acres owned by clubs, and 136,335 acres owned by conservation groups FIGURE 4 Roughly 740,000 Pennsylvanians own the remaining 8,428,507 acres of private forest. Of concern here is the parcelization of the forest — when more and more people own smaller parcels of forest. In 1980, the average forest landowner in Pennsylvania owned just under twenty-five acres, and today the average ownership is 11.4 acres.3

A private forest landowner may manage their land for a combination of reasons, including wildlife habitat, carbon sequestration, firewood, recreation, hunting, and sometimes just for its aesthetic value. It is important though, to realize that these goals can be achieved, and often amplified, while also managing the forest for its timber resource. The decisions a forest landowner makes or doesn’t make have an impact on the quality and value of the forest and its resource, now and in the future.

Pennsylvania hardwoods are known throughout the world for their quality, beauty, and sustainability. Our forests are the source of high-quality logs and lumber and diverse secondary wood products. With 16.6 million acres of forestland, Pennsylvania has the most abundant hardwood forest in the nation. The quality of our lives as Pennsylvanians and the quality of the forest within the commonwealth are enriched and multiplied by the forest products industry, which ensures sustainability through well-managed working forests. ■

FIGURE 3 The forest volumes have been increasing since 1955. Today Pennsylvania’s forest has 5.3X the amount of forest volume compared to 1955. Based off 2019 US Forest Service Forest Inventory Data.

FIGURE 4 Ownership categories of Pennsylvania’s forest based off 2019 US Forest Service Forest Inventory Data.

CITATIONS

1. Concessions to the Provence of Pennsylvania — July 11, 1681, The Avalon Project, Yale Law School, https://avalon.law.yale. edu/17th_century/pa02.asp

2. “The Economic Impact of Agriculture in Pennsylvania — Team PA Foundation.” The Economic Impact of Agriculture in Pennsylvania: 2021 Update, Econsult Solutions Inc., 2021, https://teampa.com/ wp-content/uploads/2021/04/TeamPA_ Agriculture2020EISUpdate_FINAL-1.pdf.

3. James C. Finley Center for Private Forests

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 15

Jonathan Geyer is the Executive Director of the Hardwoods Development Council, a Bureau within the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture responsible for the promotion, development, and expansion of the state’s forest products industry.

GRAPHIC: UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE PHOTO: CALVIN NORMAN

The forest carbon cycle, from the United States Department of Agriculture.

CARBON MARKETS IN THE WOODS

The Penn State College of Agricultural Sciences owns 140 forested acres in central Pennsylvania. The land was farmed until the mid-1800s and consisted of fields and pastures when Penn State took ownership. The trees returned when agricultural operations ceased and what grew back is typical of the area — an oak-hickory forest with a small amount of eastern hemlock and eastern white pine. It has been stewarded through the decades by the careful management of several foresters, including Jim Finely, David Jackson, and myself.

During its early stage of growth, the land did not look like a forest. It was a field of golden rod and raspberries. There were trees but they were small, and being trees, they took time to grow. This field was not barren, but full of life, including animals like Eastern Bluebird, American Woodcock, and red-tailed fox. After 10 years, the old field was dense with young trees that provided a home to many species of wildlife like Ruffed Grouse (the state bird), Gold-winged Warbler, and eastern cottontail. As time passed and the forest aged, the trees competed for space, light, and nutrients. This competition changed the habitat, so the animals that had lived in the young dense saplings left and were replaced by the likes of Black-capped Chickadee, gray tree frog, and the Red-tailed Vireo. The ax also returned to the forest. Under the supervision of a forester, it was used to reduce competition and release high-value trees like white oak, northern red oak, and shagbark hickory.

Eventually, the forest fully matured, and the wildlife that called it home changed again. Black bears, Pileated Woodpeckers, and Great Horned Owls arrived. Throughout the life of this forest, trees grew and pulled carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and turned it into sugar and oxygen in their chloroplasts with the help of water, nutrients, and sunlight. And as they grew, they released oxygen into the air. Capturing carbon dioxide is the

BY CALVIN NORMAN

often discussed but rarely seen act of sequestration. Keeping it is known as carbon storage — another important act.

As with many forests, long-term management plans were set in place. The goal for this forest was to ensure that it could provide an educational experience for stakeholders, a place for wildlife to live, and a source of income that would pay for future forest improvements. Eventually, it would have been harvested as generations of forests had been before, but due to an unforeseen event, the harvest happened earlier than anticipated.

Hemlock woolly adelgid, a non-native insect, attacked the eastern hemlocks, and within two years of its appearance, all the hemlocks were killed. No longer could Northern Flickers feed in their branches and porcupines spend a night in their boughs, nor could white-tailed deer take shelter in a storm. This mass die-off forced us to accelerate our harvest plans, as this piece of the woodlot, or stand, was roughly one third hemlock. To ensure the forest grew back, and with the goals of providing educational opportunities, wildlife habitat, and income, Jim Finely and David Jackson initiated a shelterwood harvest. This type of harvest consists of two to three cuttings which allow for an adequate amount of light to reach the forest floor, resulting in the regeneration of oak and hickory.

Pictured top left, is the forest seven years after the first harvest, which occurred in 2012. This harvest removed 48,970 board feet of saw timber (a piece of wood that is 12 in x 12 in x 1 in) which is cut from large diameter logs relatively free of defects. This timber was sold to a local sawmill to create lumber for solid wood products like floors, cabinets, and furniture. The harvest captured 135 tons of carbon (CO2e). Wood that could not be sold for sawlogs (too small or not high quality) was sold as pulp, to be shredded or chipped to make paper, oriented strand board or fiberboard. We sold 1,294 tons of pulpwood, which equates to 1,067 tons of carbon.

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 17

In total we captured 1,192 tons of carbon, some of which would go into creating high-value long-lived wood products, while keeping carbon out of the atmosphere. The harvest generated $12,860 in revenue and contributed to the regeneration of the forest, which is again full of a wide variety of birds, plants, and amphibians. Within the next two years, we plan to remove the remaining large trees to allow the young trees beneath them to grow.

The money from the harvest was used to erect deer fencing — an 8 ft tall woven wire fence — to protect young sapling from the overabundant deer, whose browsing would kill some trees and prevent others from growing past the size of shrubs. This cost us about $8,500 (about $3 a foot). After the trees grew to a size large enough for the deer to no longer be a problem, we paid $3,200 to take the fence down, roughly breaking even. We also managed invasive plants like Japanese stiltgrass, multiflora rose, and oriental bittersweet that would have prevented the regeneration of saplings.

This experience at Penn State is not unique. Pennsylvania is home to roughly 16.6 million acres of forestland, nearly 70% of which is held by private landowners. Pennsylvania is the number one exporter of hardwood lumber in the US and has been for many decades, as our forests increase in volume by about 2 billion board feet a year.

Unfortunately, there are threats to forest health. These threats include non-native forest pests, invasive species, and climate change. Addressing these threats would not be possible without financial support for many landowners. Traditionally, landowners relied on the money brought in by harvesting — with as much as 90% of harvest income coming from the sale of sawlogs. With forest management becoming more expensive, there is increased interest in carbon markets that would allow landowners to ensure that forests sequester and store carbon in the trees and soil.

Trees have been around for 200-370 million years, depending on the species, which has given them plenty of time to perfect carbon capture through photosynthesis. Plants are so effective at this process that they changed earth’s atmosphere from mainly carbon dioxide to a high concentration of oxygen. At that time, most of Earth’s organisms were photosynthetic and relied on carbon dioxide — rather than oxygen — for life. Today we face the opposite problem: there is an increasing amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide, and we (humans) are searching for a solution. While there is not one solution to this complex issue, trees play an important role in reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide.

While carbon is not new to forests, the market for carbon is. The idea behind carbon markets is to allow carbon emitters to meet emission reduction goals by paying someone, in this case a forest owner, to take a new action that captures carbon — this is called additionality. The other key term in carbon markets is permanence, which is how long the carbon is locked out of the atmosphere. If permanence is short, the impact on the climate is minimal. To make a long-term impact on reducing climate change, carbon dioxide must be taken out of the atmosphere for a long time. In forest carbon markets, only carbon stored in trees is measured (even though soils in eastern forests can contain almost as much carbon as the trees) because trees are much easier to measure, grow, and manage.

There are two kinds of carbon markets, regulated markets that are required and regulated by governments and voluntary markets, where there are no regulations and participation is voluntary. In both regulated and unregulated markets, credits are created in many ways, such as installing renewable energy, capping fossil fuel, and in forests.

The largest regulated market is the California Air Regulatory Board (CARB), which requires companies/emitters to meet California state emission standards. Carbon credits in this market are created by people or companies inside or outside of California, so forest owners in Pennsylvania can and have sold carbon credits to participating California entities. In 2021, Pennsylvania forest landowners could earn as much as $15 per acre by participating in CARB, although actual earnings varied by forest and contract terms.

Unlike regulated markets, participants in voluntary markets are not required by a government or regulator to offset their emissions — they are offsetting by choice to meet Energy, Social, and Governance (ESG) goals, net-zero emissions promises, or for other reasons. The voluntary market is a rapidly growing sector, especially in Pennsylvania, and accounts for much of the overall growth in carbon markets. Demand for voluntary credits is increasing as the threat of climate change becomes more pressing and by stakeholder demand. Through the purchase of credits, carbon market participants seek to be part of the solution to climate change.

Because the voluntary market is largely unregulated, the actions required to participate vary; in some programs, landowners are paid to control invasive species, others pay landowners to regenerate new forests by harvest, and others pay landowners not to harvest. The time that landowners engage in these programs also vary, as well as the perma-

18 WINTER 2023 | context | AIA Philadelphia

nence. The credit purchaser pays the forest owner to undertake a change of behavior that impacts carbon. The definition of some of the measurements in voluntary market can also vary by program — for example a program may offer 1.2 credits per acre of forest while others may say there are 2 tons of carbon per acre. When buying credits in voluntary markets, it is important that buyers do their homework and understand what they are purchasing.

In 2021, Pennsylvania forest landowners could earn $4-10 per acre per year by participating in voluntary markets. While these programs can be a potential income source for forest owners, not every program is appropriate for every forest. For example, a landowner was recently offered a contract that would prohibit harvesting their late maturity aspen forest for 60 years. However, to maintain the health of the forest, the aspen would need to be harvested in 20 years. The owner turned down the contract to ensure their forest was productively growing and sequestering carbon. Every forest is different, and management needs to be tailored to each forest.

The construction industry plays a large role in forest management as it is one of the main customers of forest products. A tree’s monetary worth is nothing until it is cut down (squirrels, birds, and salamanders can’t live without them, but they do not pay rent). By specifying sustainably managed, American-grown hardwoods, architects can support forests, carbon sequestration, carbon storage, and create a home for the diverse species of wildlife that call the forests home. Building with wood means building with carbon and increasing carbon storage, while building with other materials releases carbon. The comparative carbon benefits of using wood instead of other building materials is known as the substitution effect.

Trees sequester carbon by growing, and store captured carbon for long periods of time in their wood. Sustainably managed Pennsylvania forests provide habitats for a diversity of wildlife, employ thousands of workers, pay for increasingly important forest management, and store carbon that would have been released through natural decomposition. Using forest products and supporting forest management is not going to stop climate change, but it can certainly help slow it.

Calvin Norman is Assistant Teaching Professor of Forestry in the Penn State College of Agricultural Sciences. He is a Wisconsin native, who moved to Pennsylvania after earning a Master of Science degree from Clemson University. Prior to that he worked in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, where he managed 10,000 acres of forest.

Calvin Norman is Assistant Teaching Professor of Forestry in the Penn State College of Agricultural Sciences. He is a Wisconsin native, who moved to Pennsylvania after earning a Master of Science degree from Clemson University. Prior to that he worked in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, where he managed 10,000 acres of forest.

PHOTO: CALVIN NORMAN GRAPHICS: UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

The ins and outs of carbon and the land, from the United States Department of Agriculture, above. A pile of sequestered carbon harvested from Penn State’s land, below.

Penn State’s land, seven years after the harvest.

MASS TIMBER STRUCTURAL FORM IN ARCHITECTURE

BY JIM DESTEFANO

BY JIM DESTEFANO

20 WINTER 2023 | context | AIA Philadelphia

During the era of modern architecture, one mantra of architects was “Form Follows Function.” A popular manifestation of that doctrine was the architectural expression of the building’s structural framework, exposing and celebrating the bones of the structure. Then in the 1980s, a tragic thing happened to the world of architecture — it was called “Post-Modernism.”

Post-Modern architecture changed everything. Architecturally exposed structures were no longer in vogue. Form follows function was discarded without a tear. Architects no longer

collaborated with engineers on design in the same way. Structure was now to be concealed behind the veil of architectural representation. With the demise of Post-Modern architecture, expression of structure in architecture is back in a big way and mass timber is leading the movement. The architect Louis Kahn alleged to have once had a conversation with a brick. As the story goes, he asked the brick “what do you want to be?” and the brick replied “I like an arch.” Had he asked the same question of a tree, the reply most certainly would have been “I like mass timber.”

Mass timber structures are cost effective and sustainable, but the most compelling reason for architects to choose timber is for the benefits of exposed wood. There is something inherently spectacular about the look, smell, and feel of architecturally exposed timber. Nothing beats timber for architectural drama when a more mundane structure just will not do. Unfortunately, all too often a mass timber design is little more than a direct substitution of glulam timbers for steel girders and cross laminated timber panels (CLTs) for a concrete slab. When done right, however, mass timber structures can be way cool.

SOMETHING OLD AND SOMETHING NEW. Mass timber is not a new idea, just a new name. A lot of people have heard the term “mass timber” tossed around in the last several years, but not everybody has a clear understanding of what it means. Mass timber used to be referred to as “heavy timber” and model building codes classified it as “Type IV construction”.

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 21

Traditional Timber Frame, Hermitage Club, Haystack Mountain, VT, above. Curvilinear glulam structure, Mystic Seaport Museum — Centerbrook Architects, left.

THE MOST EXCITING TREND IN ARCHITECTURE TODAY IS MASS TIMBER CONSTRUCTION — WHERE THE STRUCTURE IS THE ARCHITECTURE.

PHOTOS: JEFF GOLDBERG ESTO, SOUTH COUNTY POST & BEAM, TOP RIGHT.

Mass timber is a type of construction made up of big pieces of wood that, unlike light wood frame construction, burn slowly. Because mass timber structures maintain their integrity during a fire, without the need for layers of fire-resistant materials, they are suitable for larger buildings and building codes now recognize that.

Timber buildings have been built for over 4000 years, since bronze-age humans developed the technology to forge sharp tools that could hew trees into square timbers and fashion mortise and tenon joints. Timber structures were the dominant construction type in Europe, Asia, and North America until 1850 when balloon frame wood structures began to displace traditional timber construction. By the turn of the 20th century, timber construction was nearly extinct and structural iron construction was becoming commonplace for larger structures.

Following World War II, glued-laminated (glulam) timber construction became popular for long span and architecturally exposed applications such as churches and gymnasiums. At the time, if you wanted a structure that looked like timber, glulam construction was your only choice. This is no longer true. In the 1980s, traditional timber frame construction, sawn timbers with intricate joinery, experienced a revival and soon re-entered main stream construction practice. For some applications, traditional timber frames began to displace glulam construction for architecturally exposed structures.

So, what’s new? Timber panels are new: cross laminated timber (CLT) panels. CLTs have been used in Europe since the 1990s, but have only been available in North America for a little more than a decade. Today there are several major manufacturers of CLTs in North America and some European producers continue to be competitive in the US market. The availability of timber panels has stimulated interest and excitement in the architectural

were harvested. Mass timber components are laminated from modest sized lumber that has been harvested from sustainably managed forests. You no longer need to cut down a large tree to get a large timber.

CROSS LAMINATED TIMBER. CLTs have often been described as “plywood on steroids”. They are made up of alternating plies of dimension lumber that have been planed to 1 3/8” thickness. Like plywood, each ply is oriented perpendicular to its adjacent plies. Common CLT layups are 3 ply (4 1/8” in thickness), 5 ply (6 7/8”), and 7 ply (9 5/8”). CLT panels are typically 8 feet or 10 feet wide and can be up to 64 feet long.

CLTs are made from a few different wood species with spruce and Douglas fir being the most common. Since each CLT producer tends to utilize only one particular wood species, it is important for architects to keep an open mind about species to get the most competitive pricing and the most environmentally responsible outcome. There is generally not a significant difference in appearance between the available species. CLTs are not a local product, however, and the panels for a project in Philadelphia may be coming from Canada, the Pacific Northwest, or Europe.

REACHING FOR THE SKY. High-rise construction has long been the exclusive domain of structural steel and reinforced concrete, but that is no longer the case. Mass timber is now a player in the high-rise market. The 2021 International Building Code (IBC) has expanded Type IV construction to permit mass timber buildings up to 18 stories. The rub is, with taller buildings, much of the timber is required to be fire protected. In many cases, it likely does not make sense to build with timber and then cover it up with drywall and hung ceilings.

The recently completed 25-story Ascent apartment building in Milwaukee boasts 21 stories of mass timber over a concrete parking structure. It is now the tallest mass timber building in the world. The Ascent building was built under a special exception to the Building Code that allowed it to exceed the height limits in the 2021 IBC. As far as tall buildings go, 21 stories may not sound all that impressive, but for timber construction it is a big deal. It is unlikely that mass timber is going to completely displace structural

Glulam structure, Portland International Jetport, Portland, ME, left. Nordic Structures CLT Plant, right.

PHOTOS: ROBERT BENSON LEFT. STEPHANE GROLEAU, BELOW.

steel and reinforced concrete for high-rise construction, but we will certainly be seeing more tall mass timber projects in the future.

FIRED UP. It is a common misconception that because wood is combustible, wood buildings perform poorly in a fire. While that may be true of light wood frame construction, it is not at all true of mass timber. Actually, mass timber structures perform better than unprotected structural steel during a fire. Timbers will develop a char layer on the surface when exposed to a flame. The char layer progresses slowly and insulates the wood beneath it from the heat of the fire, permitting the timbers to continue to carry load. When timber structures do eventually fail during a fire, they do not fail suddenly. They typically give firefighters ample warning prior to a collapse by making loud cracking and hissing noises. The exception is when steel connection hardware is exposed to the fire, the connections will fail suddenly. It is important to protect steel connection hardware either with an intumescent coating, or by having all steel hardware embedded inside the timbers where the wood can protect the steel from the fire.

ACOUSTICAL CONSIDERATIONS. The acoustics of a mass timber structure require special attention. Bare timber floors will readily transmit sound, particularly impact sound associated with foot falls. To address sound transmission, it is common to install an acoustical mat over the timber floor with a concrete or gypcrete topping slab. Exposed timber ceilings will also reflect rather than absorb sound. This can result in unpleasant sound reverberation in public spaces such as restaurants. The introduction of sound absorbing elements should be considered.

STRUCTURAL CONSIDERATIONS. The design of mass timber floor systems is typically not controlled by strength, but by floor vibration. Floor vibration associated with foot traffic must be evaluated. Designing to an arbitrary static deflection limit such as L/360 or L/480 will not ensure that a floor structure does not feel bouncy.

HYBRIDIZATION. There is no shame in not being a purist. Mass timber plays well with other structural materials. Often the right structural solution for a project is not a pure mass timber structure, but a hybrid solution.

CLT floor and roof panels with glulam joists, structural steel girders and col umns, and a concrete topping slab of ten makes for a very efficient structure. Of course, as discussed above, steel elements often require an intumes cent coating to achieve a fire resistance comparable to the timber elements.

GETTING THE DETAILS RIGHT. was correct—“God is in the details,” especially with mass timber. Timber engineering is all about the connection details. Sizing the timbers and panels is the easy part; designing the timber connections is the challenging part. Many engineers that are inexperienced with timber engineering will attempt to connect timbers in a fashion similar to structural steel construction, with bulky side plates and lots of bolts. While this approach sometimes works, it is seldom the most practical, elegant, or efficient way to make a timber connection and it is almost never the most aesthetically pleasing solution for an exposed structure.

Timber is an organic material that shrinks and swells seasonally with changes in humidity. Failure to consider timber dimension changes associated with moisture content when detailing connections can lead to disappointing results. Poorly detailed steel connection hardware can restrain shrinkage, resulting in splitting of the timbers. Detailing for durability is crucial. It is essential that timbers be kept dry and details that trap or collect water should be avoided. If a timber structure is exposed to the elements, preservative treatment is essential.

COLLABORATION. The finest mass timber buildings are the result of a collaboration between an architect with vision and an engineer who understands timber. Sadly, all too often, this engineering is delegated to a contractor and the timber engineer becomes involved too late, after the design is set. To achieve an efficient and elegant mass timber structure, the architecture and engineering collaboration should begin early, during the conceptual design phase of the project. ■

Jim DeStefano, P.E., AIA, F.SEI is the President of DeStefano & Chamberlain, Inc. structural and architectural engineers, located in Connecticut. Jim has over 40 years of experience designing timber structures. He is a founder of the Timber Frame Engineering Council (TFEC) and a member of Timber Edge.

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 23

Charred timbers continue to sustain load after a devastating fire, top left. Hybrid CLT and structural steel framing, Stamford Media Village, top right.

PHOTOS: JDESTEFANO & CHAMBERLAIN

SEEING THE FOREST FOR THE BUILDING

BY KIEL MOE

Recent mass timber buildings are objectively neither good nor bad in ecological terms. Through their respective building processes, they might alternately cultivate life in healthy forests or obliterate a forest ecosystem. Mass timber buildings may either be a carbon sink or a source of carbon emissions. The latter is most likely the case when architects consider mass timber simply as a substitute for steel or concrete construction. In this substitution mentality, the core problems of how architects conceive construction persists too often they continue to think of a building as a composed, constructed object rather than an act of composition — a rearrangement of intricate planetary processes. They errantly think of a building as a noun, rather than as the hardened edge of verbs and dynamic processes that are much larger and much smaller than a building. In doing so, such architects externalize consequential matters of conceptual and practical concern.

The upside of recent timber building interest is that some architects are beginning to relearn what modernity trained architects forget: that building is inherently terrestrial, and to understand building is to understand the range of ecological, social, and political relations that engender building. For instance, architects are beginning to understand the profound, but obvious, fact that timber buildings come from forests. To truly know timber building is to know forest building as well. Ultimately, to design timber buildings in an ecological manner is to understand the soil conditions of the forests supplying the wood.

Take, for instance, the different forests in New

England and Quebec. The boreal forests of Quebec are predominantly Black Spruce stands, often held in very large ownership tracts, all in the resource extractionintensive context of the Canadian economy. This more singular species, its socio-economic context, and the specific material properties of that species all suit the production of cross-laminated timber panels quite well. By contrast, New England presents a very different forest, characterized by a blend of hardwood species with a changing coniferous mix. The small landowners who own much of this forest often retain often retain a misguided conversation ethic in which trees are never cut, even at the price of forest health, biodiversity, water quality, and resilience. In the New England context, cross-laminated timber panels are not at all obvious as a forest product. Smaller timber components, made in smaller and more diverse facilities, from a more diverse mix of species and harvesting practices suit the New England forest.

Such observations about the specificity of forests are essential to how architects might consider the reciprocities of timber building and forest building as coupled terrestrial activities. The ultimate merits, or burdens, of timber building will come to bear not only on the performance of a particular building, but also on that building’s contributions to forest building. For instance, in aesthetic terms, if a conventionally beautiful mass timber building is the result of vulgar forestry practices and material geographies, then it should be considered less aesthetically and architecturally satisfying. If a mass timber building’s shallow claims on carbon neutrality only serve to mask

24 WINTER 2023 | context | AIA Philadelphia OPINION

ill-considered and carbon-emission intensive transportation, production, and forestry dynamics, then the merits of its architecture are ultimately in doubt. Consider that the trees on a fully loaded logging truck contain a finite amount of sequestered carbon. That truck can only drive so far before it has emitted as much carbon as locked in the logs it is transporting. All this before it is pushed through an emission-laden timber processing and fabrication process, and all that before that timber is transported once again to a construction site. To adequately consider mass timber building is to rethink the systems and boundaries of conventional construction. This prompt is not about stubborn localism as much as it is knowing and designing, the whole construction ecology of contemporary construction. To build with mass timber is a territorial proposition as much as it is a proposition for a particular client on a particular site.

It is also a unique molecular proposition. Timber used in construction has a unique set of material properties. Its cellular, solid material composition allows it to absorb heat and moisture, unlike other materials. This is part of why, colloquially, we think of wood as a “warm” material. There is science behind that perception. Imagine blocks of wood and steel in front of you that are the same temperature. After touching each you would remark that the steel feels colder and the wood warmer, even though they are the same physical temperature. The wood has a lower ‘thermal effusivity’ which quantifies the propensity of a material to transfer heat to or from another material, in this case your fingertips. You lose more heat to the steel, hence the difference in thermal perception. Accordingly, an all-wood building will provide a very different thermal experience than that of other materials. Perhaps timber buildings should thus have a different energy code — a wood building could be quantitatively cooler in air temperature yet feel warmer than a building surfaced with other materials.

Architecting based on the unique molecular properties of timber has further implications. Engineer Salmaan Craig is currently refining an approach to uninsulated solid timber buildings that meet, or beat Passivhaus standards. In Craig’s approach, calibrated holes in the solid timber wall

transform the wall into a heat exchanger. Interior heat moving through the solid timber heats incoming ventilation air. The approach eliminates not just insulation but also mechanical heat exchangers. Absolving building of the carbon-intensive, randomly sourced layers of construction and mechanical systems goes a long way towards positive environmental impacts through building. Much like the unique properties of a forest, timber building today involves deep forays into the material properties of timber.

From the molecular to the territorial, architects and engineers are beginning to re-engage the fundamental terrestrial character of building. They are beginning to see the forest for the building. They are also beginning to peer

TO BUILD WITH MASS TIMBER IS A TERRITORIAL PROPOSITION

into novel molecular architectures as they pioneer a new paradigm of carbon-positive building. This change in practice is not the result of a change in building materials used in our building environments. It is a result of a change in how designers think about and characterize building at a range of scales through a range of inherent processes. It is a result of thinking through the construction ecology of building, not with the aim of minimizing environmental impacts but, rather, with the goal of maximizing the good that design can achieve at a range of scales. This begins with the recognition of building design as an inherently terrestrial act. ■

Kiel Moe, FAIA, FAAR is an architect, researcher, and writer. He was awarded a Fulbright Distinguished Chair in Helsinki; the Gorham P. Stevens Rome Prize in Architecture, the Architecture League of New York Prize, and the American Institute of Architects National Young Architect Award. His published books include Unless: The Construction Ecology of Seagram Building; Empire, State & Building; Wood Urbanism: From the Molecular to the Territorial; Insulating Modernism; and Convergence: An Architectural Agenda for Energy.

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 25

DEVELOPING CRAFT & COMMUNITY

BY LEHIGH VALLEY NATURAL BUILDERS GUILD, PETER CHRISTINE, AND NICKY RHODES

Since 2016, the mission of the Lehigh Valley Natural Builders Guild has been to grow and support a network of skilled natural builders in the Northeastern Pennsylvania region through outreach and education, skills and methods training, resourcing, collaboration, and service. As natural builders, we draw from traditional craft and modern science to create beautiful, high performance, site appropriate structures using minimally processed locally sourced materials with low embodied energy.

1As a longtime natural building enthusiast and Guild member, Dick Lane was eager to turn his early 19th century Allentown farmstead into a laboratry for experimenting with natural materials. In fall 2021, the Guild organized a series of free, hands-on workshops centered around building a traditional post and beam gazebo.

4 The beams, being test fit here, were joined with jack mitered half lap joints. This is one example of the timber framing techniques we used to minimize manufactured components.

5 Ash is a strong hardwood whose local population is being devastated by the Emerald Ash Borer beetle. We chose to use this species for the superstructure.

26 WINTER 2023 | context | AIA Philadelphia

2Building this post and beam gazebo required many hands. Participants ranged from seasoned craftspeople to some who had never picked up a saw.

3All of the lumber in the gazebo was milled locally. For the foundation we selected sunken posts of untreated black locust, which is naturally rot and pest resistant. The floorboards and joists were made of oak and finished with boiled linseed oil.

6 The roof purlins were made from live edge pine slabs, leftover from the process of milling dimensional lumber.

7 Visit us at www.naturalbuildersguild.org to learn more about the community and information about monthly meetings (open to all), and to get involved in upcoming projects!

Contributors: Nicky Rhodes is an architectural designer focused on innovative, communityoriented practices of sustainability. He served as Vice Chair of the Lehigh Valley Natural Builders Guild through summer 2022 and is currently studying architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Peter Christine is a homesteader and home remodeling contractor. He learned about the designbuild process by building a small passive solar home on his farm in Kunkletown, PA. He served as Chair of the Lehigh Valley Natural Builders Guild in 2020.

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 27 PHOTOS BY LEHIGH VALLEY

BUILDERS GUILD

NATURAL

EXPRESSION

RED CLAY PASSIVE

Bright Common

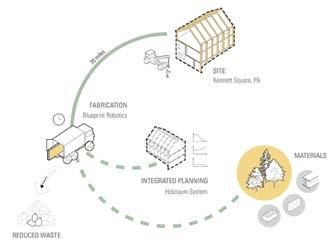

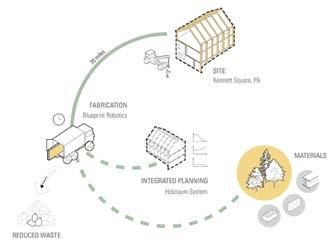

Red Clay Passive considers how a site with a rich cultural past can adapt to a climate-variable future. This Passive House sits on the footprint of an earlier farmhouse and is bookended by new volumes: a winter room and a garage workshop. Ancillary outdoor spaces such as a trellised breezeway, raised decks, and a vegetable garden encircle the home to offer all-season connections to nature.

The home’s exterior takes inspiration from the site’s existing structures and adopts the restrained notions of Shaker architecture; restricting the use of decorative elements in a pursuit of function. This aesthetic simplicity allowed funds to be directed towards assemblies, systems, and passive energy strategies.

The design prioritized passive strategies, a healthy indoor environment, and low carbon (embodied and operational) from the onset. With an efficient window-to-wall ratio, prime southern exposure, and air-tight assemblies, this all-electric house required minimal systems. A groundsource heat pump takes advantage of the earth’s constant temperature to efficiently heat and cool indoor air without burning fossil fuels while a roof-top solar array allows the home to achieve net positive energy. Downhill, a sunken cistern collects rainwater for reuse in the garden. On the interior, an energy recovery ventilator continuously replenishes stale air with fresh, filtered, outdoor air.

The team utilized modular construction to advance

the project’s low-embodied carbon goals and reduce construction waste. These assemblies are composed of wood framing, blown-in cellulose insulation, plywood, and exterior wood-fiber insulation. Compared to traditional stick-built framing, the modular assemblies greatly reduced on-site waste, allowed for quicker installation during construction, and minimized disruption to the existing landscape. The finished product is an air-tight carbon sink that passes the rigorous requirements set in place by the Passive House (PHIUS) standard. ■

PROJECT: Red Clay Passive

LOCATION: Kennett Square, PA

CLIENT: Private Homeowner

PROJECT SIZE: 3,375 gross sf

PROJECT TEAM:

Bright Common (Architect)

DL Howell (Civil Engineer)

CKS Structures Inc. (Structural Engineer)

Hugh Lofting Timber Framing (General Contractor)

Blueprint Robotics (Modular Fabricator)

Holzraum System (Energy Modeler)

DBS Energy (PHIUS Verifier)

DESIGN

PROFILE

PHOTO: SAM OBERTER

PHOTO: MIKE MAGEE; DIAGRAM; COURTESY OF BRIGHT COMMON

PHOTO: SAM OBERTER

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 29

WL GORE CAPABILITIES CENTER DIGSAU

W. L. Gore & Associates is a global materials science company focused on discovery, product innovation, and a commitment to improving lives. Their Capabilities Center, located in Newark, DE, is an interactive space where customers, partners, and visitors gain insight into Gore and their advanced material capabilities.

DIGSAU’s adaptation of an existing building choreographs a sequence of experiences that showcase Gore’s capabilities, culture, and commitment to innovation. The design is conceived as a journey through the process of a material’s transformation from its natural state into a highly engineered product. In this way, wood is used as a metaphor for Gore’s product innovation and to recall a connection to the natural world which is at the core of the company’s philosophy.

The journey begins at the building’s entrance with a highly

transparent facade connecting to a view of the landscape beyond from heavy timber seating. Visitors enter the exhibit space through a sculptural corridor featuring motion-triggered lighting elements integrated into a CNC-milled plywood wall evoking an awareness of the transformation from a raw material into a highly-processed product. The passageway serves as a gateway, subtly introducing themes, materials, and visual effects that recur throughout the Capabilities Center. Along the length of the corridor, the wall panels morph from a milled, organic and highly textured surface to a smooth finished panel.

From apparel to aerospace, the Capabilities Center provides a comprehensive spatial and interpretative experience of Gore’s work. Wood paneled display areas provide the context within the larger space for both low and high tech exhibits featuring a combination of objects, video, photography, and dynamic graphics. At the heart of the Capabilities Center is an intimate theatre space clad in wood panels on its exterior and felt on its interior, offering visitors a hands-on experience with an array of Gore products. n

30 WINTER 2023 | context | AIA Philadelphia

PHOTOS: HALKIN MASON PHOTOGRAPY

PROJECT: WL Gore Capabilities Center

LOCATION: Newark, DE

CLIENT: W. L. Gore & Associates

PROJECT SIZE: 8,500 sf

PROJECT TEAM:

DIGSAU (Architects)

Arup (MEP Engineer)

Bluecadet (Exhibits)

Whiting Turner (General Contractor)

DESIGN PROFILE

ALCHEMY COFFEE LO Design

Alchemy Coffee is a third-wave café in Rittenhouse Square, Philadelphia, designed by boutique architecture firm, LO Design. A collaboration with a talented, passionate client resulted in a unique interior reflecting the artisanal nature of the shop’s high quality products and the mixed Japanese and West African heritage of its owner and lead coffee connoisseur, Chris Stone.

Alchemy’s new space serves as a peaceful refuge for customers along a bustling section of 21st Street in the heart of Center City. The same attention to detail typically directed towards espresso drinks was focused on creating a shop that rivals the interiors of some of the best coffee bars in the world. Situated along the ground floor of a historic residential building, Alchemy welcomes visitors with a soft, bright palette using wood and plaster to bounce light within the space. A minimalist, bleached ash barista counter and pastry case is flanked by curved plaster walls, mirroring a seating bar on the opposite end of the shop. Brass kickplates give these two volumes the appearance of hovering over the neutral porcelain floors, while the altered shape of the room softens the perspective of the narrow space.

LO Design guided the client through many challenges throughout the project. Halfway through design, lease negotiations forced the owner to change the shop’s location and the initial concept was adapted from a tall, triangular space to a rectangular floorplan with low ceilings. Further, the zoning of the store, despite previously being a café, required a use variance. The team confronted various material shortages, delays, and contractor mishaps as construction proceeded through the worst of the pandemic.

Despite its size, this detail-focused project took nearly three years to complete. Today, it stands as one of the most popular local coffeeshops, and Alchemy’s custom-designed ash café tables are rarely vacant. n

PROJECT: Alchemy Coffee

LOCATION: Philadelphia

CLIENT: Alchemy Coffee

PROJECT SIZE: 1000 sf

PROJECT TEAM:

LO Design (Architect, Interior Designer, Project Manager)

HiveMind Construction (General Contractor)

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 33

DESIGN PROFILE

PHOTOS: ROUND THREE PHOTOGRAPHY

Benchmark School Innovation Lab Media, PA Cicada Architecture / Planning Inc. 918 Delaware Avenue Philadelphia, PA Harman Deutsch Ohler Architecture Filigree House Philadelphia, PA Moto Designshop Designing your vision, one detail at a timeTM orndorf.com (610) 896-4500

2022 DESIGN AWARDS 2022 DESIGN AWARDS

More than 350 AIA Philadelphia members and friends gathered in-person at The Fillmore to celebrate the 2022 Design Awards honorees including the winners of the John Frederick Harbeson, PEA Prize, Young Architect, Alan Greenberger, and the Paul Philippe Cret awards. Turn the page to learn more about this year’s honorees and the 20+ projects that made the cut. >>

AIA Philadelphia | context | WINTER 2023 35

LEONARD AND HELENA MAZUR HALL, PAGE 45

BARNEGAT LIGHT RESIDENCE, PAGE 45

FILIGREE HOUSE, PAGE 43

GETTYSBURG MONTESSORI CHARTER SCHOOL, PAGE 44

THE JOHN FREDERICK HARBESON AWARD is presented annually to a long-standing member of the architectural community and is intended to recognize their significant contributions to the architectural profession and its related disciplines over their lifetime. The recipient of this award will distinguish themselves throughout their career by their contributions to the architectural profession, the American Institute of Architects, the education of the architectural community, and their contributions to the Philadelphia community at large.

Katherine Dowdell, AIA, has over 25 years of experience in architecture, interior design, and historic preservation, giving her a strong understanding of planning, architecture, and construction issues, particularly those encountered in older buildings. She is the founding Principal of Farragut Street Architects where she has undertaken a broad range of project types most notably 705707 S. 50th Street a conversion of two existing rowhomes into a hub for community-based small businesses and an industrial building turned residential mixed-use building at 1000 S. Saint Bernard Street. Ms. Dowdell’s steadfast, passionate, and enthusiastic mentorship and championing of her fellow architects and her finesse when advocating for a building is extraordinary. Her many years of service to the industry in various roles with the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia, the Wagner Free Institute, the Woodlands, and as an adjunct professor at Drexel University, and Jefferson University are just a few of the reasons Ms. Dowdell was honored with this award.

Since joining APM in 1990, Ms. Gray has been actively engaged in the revitalization of eastern North Philadelphia, a diverse community that has historically been comprised of Latinos and African Americans. During her tenure at APM, Ms. Gray has successfully leveraged over $280 million in investments to implement a comprehensive neighborhood revitalization strategy. She has developed over 350 units of affordable housing, which include low-income housing tax credit projects and the Pradera home development, Borinquen Plaza, and the Paseo Verde Transit-Oriented Development.

In addition to her work for APM, Ms. Gray is a civic leader serving on various boards and committees, TRF New Market Advisory Board, the Urban Land Institute, the Community Design Collaborative, and as Board President for the Philadelphia Association of Community Development corporations. She was appointed to Governor Ridge’s “Summit for America’s Future” and served from 2012-2018 and appointed to the Commission on Aging by Mayor Michael Nutter in 2011 and served in this position until 2019 under Mayor Kenny.

THE PAUL PHILIPPE CRET AWARD recognizes individuals or organizations who are not architects but who have made an outstanding and lasting contribution to the design of buildings, structures, landscapes, and the public realm of Greater Philadelphia.

Rose V. Gray, is the Senior Vice President of Community and Economic Development at Asociación Puertorriqueños En Marcha (APM), a non-profit community development corporation in North Philadelphia. Ms. Gray is being recognized for her significant contributions to the built environment in Philadelphia through her community-informed design, development, and advocacy work.

The Community Design Collaborative’s (Collaborative) ALAN GREENBERGER AWARD, named after Alan Greenberger, FAIA, and former Deputy Mayor of Philadelphia, recognizes leaders/ volunteers and AIA Members for their commitment and service to the organization’s mission. Sally Harrison , AIA, is Professor of Architecture at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture at Temple University. A registered architect, educator, and scholar, her creative work and research explore the social impacts of design. She involves her students in these questions, teaching courses in social activism, architectural and urban design, and urban history/theory. Ms. Harrison is being recognized for her significant contributions to community-engaged design and her mentorship of her students to appreciate the importance and difficulty of thoughtful and long-term investments in communities as part of a sustainable and equitable design practice.

36 WINTER 2023 | context | AIA Philadelphia

PHOTOS: COLORSPACE LABS

The annual PHILADELPHIA EMERGING ARCHITECT PRIZE recognizes a Philadelphia firm that has been established and licensed within the past ten years for its high-quality design and innovative thought.

Gnome Architects is a multifaceted residential design firm with new construction and renovation projects throughout Philadelphia and custom homes in New Jersey, Maine, and Colorado. Founded in 2014 under the name GJDesign and Architecture, Gabriel Deck welcomed Derek Spencer as firm Partner and Design Director in 2017 when the business moved into its current location in South Philadelphia’s BOK Building. Now employing a team of eight, Gnome has completed over 400 projects including new construction of a single-family home at 1513 Pine Street, the renovation and addition of an existing schoolhouse turned residence at 1850 Woodside, and the adaptive reuse of an assisted living facility located at 1723 Francis Street.

The YOUNG ARCHITECT AWARD, presented by AIA Philadelphia’s Steering Committee of Fellows, seeks to recognize registered architect(s) between the ages of 25 and 39 for their contribution to the categories of leadership, practice, and service.

Peichao Di, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, WELL AP, PMP, moved to the United States from China in 2015 to earn his Master of Architecture from the University of Pennsylvania. A valued member of CosciaMoos’ design staff, Peichao is actively involved in all phases of projects and works in the mixed-use, multi-family housing, hospitality, and healthcare sectors. His work includes several award-winning projects including The Poplar apartment building, Marriott at Pencoyd Landing, and the Hamilton Court Amenities. Mr. Di’s project experience, mentorship, and drive to give back to his community of international students are all reasons he is deserving of this award.