3 minute read

CERCOSPORA

by agweek

BY MIKKEL PATES Agweek Staff Writer

FARGO, N.D. — Cercospora beticola is the most economically damaging foliar disease farmers face, says Mohammed Khan, a Fargo-based Extension sugarbeet specialist at North Dakota State University and the University of Minnesota.

Khan has been doing his job for 22 years but the Cercospora history goes back a long time before that. Here is his look back on its history:

• 1926 — Farmers started producing sugarbeets in East Grand Forks, Minn., with seeds supplied by the company. Europeans improved varieties for yield, but with susceptibility to cercospora. American Crystal Sugar and other private companies prevented varieties that had higher cercospora susceptibility, even those which limited tonnage yields.

• 1974 — Farmers buy American Crystal, making it a cooperative. The farmer owners changed to an “open policy,” with higher yield potential but with cercospora controlled by fungicides. They used “tin” and Benlate fungicides. After two years of use, cercospora developed resistance and overtook Benlate.

• 1981 — The first major cercospora “epidemic” occurred in Minnesota and North Dakota.

• 1998 — A second big Cercospora epidemic cost American Crystal growers $40 million, and a total of $100 million for the region’s three co-ops. “We were going toward more susceptible varieties, but using one or two fungicides,” Khan said. Growers sprayed an average of 3.7 times across the growing region. Some applied fungicides nearly every week — 12 applications a year.

• 1999 — Environmental Protection Agency approves a Section 18 exemption for a QoI fungicide trade named “Quadris,” and then “Eminent,” a triazole. “That was that was the product that saved the industry,” Khan said.

• 2003 — EPA approves Headline and by 2005 fully approved Eminent and other triazoles. Fungicides controlled the disease at two applications in the northern Red River Valley, three in the southern Red River Valley, and four in Southern Minnesota.

• 2016 — Excessive and continuous rains and heat, increased the Cercospora incidence and the potential for fungus mutations that would make them resistant to fungicides. NDSU and growers asked seed companies to speed up development of resistant varieties that were becoming commercially available in 2021.

• 2021 — Growers in Minn-Dak Farmers Cooperative in Wahpeton, N.D., and Southern Minnesota Beet Sugar Cooperative at Renville, Minn., were among the first in the country to start using CR+ (cercospora resistance plus performance) beet seed.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 5

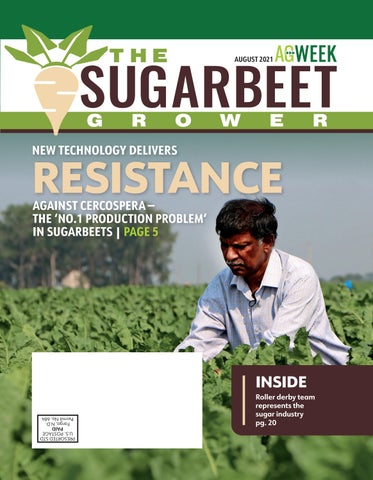

Sugarbeets are the most prominent specialty crops from southern Minnesota to the Canadian border through the Red River Valley, accounting for some $5 billion in economic activity. But that activity can be hurt by cercospora, which turns green leaves brown, shutting down yield potential.

The new CR+ (cercospora resistance plus performance), from KWS, parent company for Betaseed, commercialized seed for some growers in the southern Red River Valley of North Dakota and into southern Minnesota.

German-based genetics company KWS Saat (parent of Betaseed) in its website on the topic says about twothirds of global sugarbeet acreage has a moderate to high cercospora pressure. Cercospora is the most destructive leaf disease of sugarbeets, sometimes cutting crop yield by 50% in some places, the company says on its website..

Khan said the new technology will prolong the usefulness of other fungicide treatment.

“It’s a real game-changer,” he said, describing the technology in a private tour of his cercospora research plots near Foxhome, Minn., about an hour east of Fargo, N.D.

Khan manages research/demonstration plots annually of about 25 acres on land farmed by Kevin Etzler of Foxhome. The research is open to the public, usually replicated four times, on a scale similar to typical farm fields. Here, the MinnDak Farmers Cooperative of Wahpeton, N.D., and American Crystal Sugar Co., of Moorhead, MInn., evaluate (blind)“coded” varieties they test for various seed companies to ensure they meet minimum standards for cercospora vulnerability. Much is at stake.

Infested fields hit can easily lose 40% of their yield and about 2 to 3 percentage points of sugar — a loss of millions of pounds of sugar and millions of dollars throughout the growing regions.

“You can easily lose $300, $400, $500 per acre,” Khan said.

South to north

Cercospora since 2016 in the Minnesota/ North Dakota region has been most prevalent in the two southern coops: Minn-Dak Farmers Cooperative andSouthern Minnesota Beet Sugar Cooperative. The areas where those coops operate generally get more rainfall and heat units, which increases yields but also creates more problems with cercospora. Over the past two decades, sugarbeet yields have increased nearly 50%.

Beets are a high investment crop in the three closed cooperatives. Farmers in North Dakota and Minnesota together produce 650,000 acres of beets. Diseased plants can produce 1 trillion spores per acre.

“That’s trillions and trillions of spores are circulating. The larger the number of spores, the more mutations that can lead to fungicide resistance,” Khan said. “We are trying to kill the fungus and the fungus wants to live.”

CONTINUED ON PAGE 8

A weather station at the sugarbeet cercospora leaf spot research plot near Foxhome, Minn., provides temperature (air and soil), relative humidity and precipitation data that is correlated with a spore trap to help scientists recommend the best way to fight yield- and qualityrobbing disease. Photo taken July 16, 2021, at Foxhome, Minn.