The History of Women in Dentistry

Take advantage of membership tailored to you!

For an additional $158, you can receive the following:

• Free Early-Bird Scientific Session Registration

• Free CE Library PLUS 4 On-Demand Webinars of Your Choice

• 20% Fall Fellowship Review Course Discount

• 20% Fellowship Study Guide Discount

• Free Dental Card Services Virtual Terminal Setup

“I wanted to take advantage of all the lectures and classes that the scientific session offers, so, to get the best value, Premium Plus membership was the obvious choice.”

Mohamed H. Attia, DDS, MAGD Member since 2008

LEARN MORE agd.org/membership

The medical field has a long history of being dominated by men. Education and career opportunities in medicine and dentistry have historically been denied to women, but those barriers have been broken down over time. In honor of March as Women’s History Month, AGD Impact takes a look back at how women formally broke into dentistry, the work of female pioneers over the years, and how the women in dentistry today are helping to shape the profession’s future.

Self-Instruction article, 1 CE credit

10

Noncompete clauses appear in both the hiring documents of dental office staff and in the contracts dentists have with their own employers. Many dentists have mixed feelings about noncompetes.

Self-Instruction article, 1 CE credit

16

AGD2024 in Minneapolis: The Quintessential American Destination, Plus CE

This summer, AGD heads to the City of Lakes for its annual scientific session, the premier meeting for general dentistry.

22

March is Women’s History Month, and this month AGD Impact is proud to present a cover story that focuses on some of the trailblazing women in dentistry and the obstacles they overcame — and some of the obstacles that female dentists still face today.

I’m honored that some of the most talented dentists I’ve known are women. Dentistry attracts special individuals with academic success, an empathetic personality and great manual dexterity. The ability to diagnose, treatment plan, communicate, treat with a soft touch and provide outstanding healthcare are innate in two of my closest friends, Robin Reich, DDS, and Mary Sue Stonisch, DDS.

Robin became president of the Georgia Dental Association, and her children followed in her footsteps into the profession. Nothing has made me prouder. Mary Sue graduated after I did, and I was even able to instruct her at one point when I went back to our alma mater to teach. We have remained close colleagues and friends, watching each other’s kids grow. Her interests gravitated toward esthetics, and she became a mentor at the Kois Institute. She created a magnificent freestanding office with all modern technology. I am fortunate to be able to work with her often.

Another outstanding dentist and dear friend lives in Pensacola, Florida. Stephanie Tilley, DMD, is probably the most successful person I know. Her clinical excellence is second to none, and, because I mentor her every other month, I see her tremendous empathy and compassion toward all her patients. She has created a truly outstanding practice.

These women are some of the most organized people I know, and they manage time efficiently and effectively. They are focused, driven and have perfected their abilities to a high level, and, at the same time, they are elevating our entire profession.

More recently, two other women have entered my professional life. Jacqui and Brianna are both second-year dental students, one in Chicago and one in Cleveland. Jacqui worked in my office first as a dental assistant’s assistant, then as our receptionist. She saw a lot of dentistry and learned much about the business and how chal-

lenging it can be to interact with patients. She had to collect the revenue, too (which is certainly eye-opening). Brianna shadowed me over the holidays with such enthusiasm. It was a joy to witness her newfound excitement about that which many consider mundane after so many years in practice. I envy both women for the tremendous lives they will have in this most marvelous profession.

I graduated with eight women in my class of 72. Today, women make up nearly 60% of dental school attendees. This is great progress, but we need to do more. While more and more women are becoming dentists, this needs to be reflected in leadership. Only four women are on the ADA board of trustees, and only one woman currently serves as an AGD trustee.

Leadership roles need to be filled with competent people, and many of our best leaders today are women. Stephanie said that many men did not completely respect her standing as a female dentist in her local dental organizations early on. We need to change this perception. Support comes from many areas, including our all-encompassing AGD. Strength comes from overcoming challenges and marketing the unique capabilities of our members while elevating those members to positions where their strengths can shine and continue to move our profession forward.

I can only hope to continue the relationships with these strong, passionate women for years to come. They are all such incredible assets to their communities and our profession. We can all continue to increase female power and presence within our prestigious AGD. I may have two new female associate dentists soon and — eventually — partners. I would be lucky to have the opportunity to help pave the way for such talented female dentists to continue changing our profession for the better.

Timothy F. Kosinski, DDS, MAGD Editor

Timothy F. Kosinski, DDS, MAGD Editor

Editor

Timothy

Associate

Bruce

Director,

Kristin

Executive

Tiffany

Managing

Associate

Graphic

Robert

Periodical postage paid at Chicago, IL and additional mailing office.

*AGD members receive AGD Impact as part of membership; annual subscription rates for nonmembers are $70 to individuals/$90 to institutions (orders to Canada, add $15). Online-only subscriptions available outside U.S./Canada are $75 to individuals/$115 to organizations. Single copy rates are $17.50 to individuals/$20 to institutions (orders to Canada, add $2.50). All orders must be prepaid in U.S. dollars.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to AGD Impact, 560 W. Lake St., Sixth Floor, Chicago, IL 60661-6600.

No portion of AGD Impact may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the AGD.

Photocopying Information: The Item-Fee Code for this publication indicates that authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by the copyright holder for libraries and other users registered with the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC). The appropriate remittance of $3 per article/10¢ per page is paid directly to the CCC, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. The copyright owner’s

The fifth annual AGD Advocacy Conference instituted a new and exciting format, with two half-day sessions conducted virtually Dec. 15–16, 2023. This change allowed more than 400 members to participate. Previously, the conference was held at the AGD office in Chicago and limited to 40 participants. Additionally, all Advocacy Conference presentations are available to members through AGD’s Online Learning Center.

Conference presentations covered matters relating to advocacy in the legislative and regulatory arenas, within organized dentistry, and in regard to the dental insurance industry. The program’s primary learning objectives were to provide attendees with insights and perspective on various state and federal oral health issues, an awareness of how intra-dentistry collaborations can impact advocacy efforts, suggestions on how they can influence legislative and regulatory conversations, and a recap of AGD’s advocacy efforts on behalf of its members.

Participants from all over the country learned about the important federal and state legislative movements as well as regulatory dental practice issues affecting general dentistry. The advocacy resources AGD provides were outlined. Best practices for meeting with legislators were discussed, followed by a mock legislator meeting. Missouri State Rep. Lisa Thomas, MD, presented on the best way to communicate with your legislator, emphasizing that the key is to build a relationship with your legislators so that they will look at you as a resource when issues affecting dentistry arise in the legislature.

The conference opened with a presentation from James “JP” Paluskiewicz of Alston & Bird, LLP. Paluskiewicz is AGD’s lobbyist in Washington, D.C. Paluskiewicz highlighted some of the bills that AGD is supporting in Washington, including H.R. 994/S. 5073 to fund the Oral Health Literacy and Awareness program that the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration rolled out in 2023. Additionally, AGD is supporting H.R. 1422/S. 570, the Strengthening Medicaid Incentive for Licensees Enrolled in Dental (SMILED) Act, which would streamline credentialing for dentists to join Medicaid and reform the audit process.

Chad Olson, director of state government affairs at the American Dental Association, informed attendees about the state of medical loss ratios (MLRs) for dental insurance legislation in the states after the passage of Massachusetts Ballot Question 2 in 2022. A total of 12 states introduced dental MLR bills in 2023.

David Keller, DDS, MAGD, discussed the lay of the land regarding dental therapist laws in the United States. He clearly laid out the concerns organized dentistry has with the scope of practice these laws allow dental therapists and the arguments that can best sway state legislators. Darren S. Greenwell, DDS, MAGD, chair of AGD’s Dental Practice Council (DPC), moderated the conference and spoke about advocating for change at the state level on dental insurance issues. AGD immediate past president Hans P. Guter, DDS, FAGD, and current ADA President Linda J. Edgar, DDS, MAGD, had a conversation about ways professional dental organizations can work together and how that collaboration benefits everyone.

Ralph A. Cooley, DDS, FAGD, a member of AGD’s Legislative & Governmental Affairs (LGA) Council, discussed the history of the

Code on Dental Procedures and Nomenclature (CDT Code), the process by which it’s updated each year, and why AGD’s participation in the process is vital to ensure that it reflects procedures performed by general dentists. He also recapped the history of a new implant code (D6089, Accessing and retorquing loose implant screw — per screw), which was requested by AGD in 2022 and is included in the 2024 CDT Code.

DPC member Callan D. White, DDS, FAGD, presented an update on the status of artificial intelligence/augmented intelligence in dentistry and the technologies’ possible implications for the practice. Richard A. Huot, DDS, FAGD, also a member of the LGA Council, discussed real versus perceived challenges regarding the dental workforce. His remarks covered staffing levels for all clinical positions within the practice. Y. Brian Lee, a partner at Alston & Bird, and Jeanie Kennedy, AGD manager, dental practice and policy, discussed matters relating to federal regulatory reform and how AGD responds to federal proposals that have the potential to impact dental practices. Daniel Buksa, JD, AGD associate executive director of public affairs, provided a recap on complying with federal antitrust regulations.

The AGD Advocacy Conference is a great opportunity for any AGD members who are interested in becoming advocates for their profession to learn about the issues affecting general dentistry and the techniques of effective advocacy. Watch the 2023 conference sessions, and plan to attend the next AGD Advocacy Conference, Dec. 20–21, 2024.

Check out the latest podcast, in which host George Schmidt, DMD, FAGD, interviews Anissa Holmes, DDS, a Florida dentist and professional business coach who helps dentist entrepreneurs build successful businesses, providing them with the knowledge and business training to run, grow and scale their practices.

In this podcast, she describes how she uses social media and other tools to grow her business. She also outlines the tools and training she provides to empower other dentists to succeed, meet their goals, find the time to grow their businesses, and enjoy time with the people and projects that matter most to them.

Visit agd.org/about-agd/publications-news/agd-podcasts to listen now.

Look for the following article in the March/April 2024 issue of AGD’s peer-reviewed journal, General Dentistry.

Fracture strength of ceramic overlays with immediate dentin sealing and same-day delivery Limited research is available evaluating whether the reported in vitro benefit of immediate dentin sealing (IDS) — namely, increased bond strength to tooth structure — can be acquired in the era of same-day dentistry. The purpose of this study was to compare the fracture strengths of ceramic overlays fabricated with a delayed dentin sealing (DDS) technique or an IDS technique under 1-hour same-day or 2-week multiple-day delivery conditions. In this in vitro study, 40 extracted, healthy maxillary third molars were prepared for a lithium disilicate overlay restoration and divided into 4 groups of 10 teeth each.

Read this article and more at agd.org/generaldentistry.

The Daily Grind blog offers insights and reflections from dental students and practicing general dentists just like you.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE DAILY GRIND agd.org/about-agd/publications-news/daily-grind

The journey of women in dentistry is a truly compelling narrative that spans centuries. It is marked by resilience, determination and the persistent pursuit of professional excellence. From overcoming societal barriers to redefining the landscape of oral healthcare, women in dentistry have left a definite mark on the profession. In the 19th century — a time when women were largely confined to domestic roles — a few visionary individuals paved the way for us. Emeline Roberts Jones, a name that we often recognize as the first woman to practice dentistry in the United States, defied expectations by obtaining a dental license in 1855. Her accomplishment opened the door for generations of women to challenge gender norms and pursue careers in oral healthcare. Despite limited opportunities, Lucy Beaman Hobbs Taylor was an important figure in the mid-1800s, becoming the first woman to earn a dental degree in 1866. Her accomplishments shattered stereotypes and inspired others to follow suit. As the 20th century dawned, an increase in female enrollment in dental schools signaled a shifting tide, with women overcoming resistance and discrimination to make their mark in the profession.

representation in leadership roles remains a work in progress. Equal representation in professional organizations is at the forefront of the minds of those working for progressive changes within the profession. We work alongside the American Student Dental Association on this initiative. Mentorship and networking opportunities have been instrumental in helping to bring our voices as women forward and to show the newer generations of dentists that their contributions are important in securing the future of our profession.

Despite these positive developments, women continued to face challenges. Limited opportunities for specialization and lower acceptance rates in dental schools persisted. It was not uncommon for women to encounter skepticism and resistance in their pursuit of professional recognition. The resilience displayed during this era laid the foundation for the advancements that would follow. Hobbs Taylor’s legacy inspired subsequent generations, and, as a result, women began assuming leadership positions in dental organizations, educational institutions and private practices. However, many challenges persist. The gender pay gap remains a pressing issue, and achieving equal

As we look ahead, the future of women in dentistry is promising. The increasing number of women entering dental schools, specializing in various fields and taking on leadership roles signifies growth toward a more diverse and inclusive profession. As women continue to break barriers and challenge stereotypes, the landscape of oral healthcare is growing and evolving into one that embraces and celebrates the contributions of all its practitioners. This shift toward greater gender diversity in leadership is reflective of the changing dynamics within the profession. Many women are now serving as deans, department chairs and professors in dental schools and contributing to the education and mentorship of the next generation of dentists. Their influence extends beyond clinical practice, shaping the future of dental education and research, as well. Female leaders in dentistry are not only breaking the glass ceiling but also bringing innovative ideas to the table. Our presence in leadership positions contributes to a more inclusive and dynamic dental community. Linda J. Edgar, DDS, MAGD, the president of the American Dental Association (ADA) and a past president of AGD, exemplifies the impact of women in influential roles. Her guidance has been crucial in advancing the ADA’s mission and promoting the interests of dental professionals. Efforts to guide and support aspiring women in dentistry, coupled with advocacy for gender equity, are invaluable components of this transformative journey. With ongoing initiatives promoting diversity and inclusion, the dental profession is poised to benefit from a wealth of perspectives and talents, ultimately enhancing the quality of patient care and advancing the field of dentistry overall. As we continue to progress, it is important to embrace the vast amount of talent that we, as women, bring to the table. Our time is now — to celebrate, to empower and to propel dentistry into an era in which the contributions of women aren’t just acknowledged but are also integral to the very fabric of the profession. F

Running a dental practice (or any business) can be extremely complicated. Most dentists have multiple tasks that they handle throughout the day, and some days can be overwhelming. Within all of that is the data that is constantly coming at us to help us understand how the practice is performing, where it is strong and weak, what improvements can be made, how the staff is operating, etc. However, most dentists do not have a formula for using this information to take a pulse of their practices. As an analogy, when you get an annual physical, a set of numbers determine and inform you about your health. These include cholesterol, glucose, blood pressure and heart rate. The medical profession has figured out a formula to use on physical exams to help determine the health of each patient. Dentists have the same opportunity when it comes to understanding their practice’s health.

The first rule of understanding a dental practice is not to make the information so complex and overwhelming that it becomes hard to interpret and leads to ongoing procrastination. When it comes to understanding the general health of your practice, I recommend looking at five key numbers. These numbers are all based on production, which is the single most important factor in the success of a dental practice. As I have stated in many seminars, “If your production is at the right level and continuing to grow, your practice will always be fine.” There may be different versions of how successful a practice can be, but, when production is in the right range and continues to grow steadily over time, the practice is virtually guaranteed to be financially successful.

Production. Each practice should set an annual goal and then work to achieve that goal. If production is on track, the practice is performing at the right level. Goals have been set, and production is most likely to grow. When production begins to fall off, this is a time to dig deeper and analyze the practice to determine which triggers need to occur to bring production back.

Production per hour. Now we are moving into ratios. Looking at production alone gives you an overall indication of practice health, but understanding production per hour gives you another level of understanding of practice efficiency. Each practice will operate at a different production per hour, but the key is to improve that number on a consistent basis. There are opportunities to help improve production per hour, such as always using the right insurance codes, adding new technology, adding new services, increasing staff efficiency to save time for appointments, and increasing overall chair time. These opportunities should always be evaluated and implemented. If the production per hour is insufficient, then it is very unlikely overall practice production will reach the annual goal.

Production per provider. Looking at overall production is critically important, but you must also understand where it comes from. Many practices have partners, associates and hygienists.

These are the main producers in most dental practices, and it is valuable to know the production per provider to understand the origin of production. Knowing this data may help reveal the reasons that a provider may be experiencing lower production, such as having a senior partner who is beginning to slow down or phase out, not having sufficient coverage for hygiene appointments or consistently scheduling smaller-value appointments. By analyzing production per provider, practices can then assess what might be done to improve performance, either by a provider or a system that affects the provider.

Production per new patient. Every dentist knows that new patients are important, but very few know their real value. The financial value of a new patient, according to Levin Group data, is 200%–300% higher than a current active patient over the first 12 months. This immediately indicates that a practice that does not have enough new patients or that is delaying new patient appointments due to an overwhelmed scheduling system will end up with a lower level of production. Scheduling systems must be consistently refined to keep the right number of new patients. The schedule is a critical element in terms of achieving the annual production goal, and the production per new patient is a critical factor in making that happen.

Production to overhead. What is the overhead percentage of the practice? For general practices, I recommend 59%, which is based on models that allow a practice to invest properly but maintain the right level of profit. Keep in mind for each percentile that overhead is too high, the practice loses $1,000 for every $100,000 of production. In a $1 million revenue practice, 1% would be a loss of $10,000. However, if overhead is 4% too high, this would then be a loss of $40,000.

One of the easiest ways to lower the overhead percentage is to increase practice production. That is why knowing this statistic is so valuable in indicating when overhead is higher than the target and when production needs to be increased to bring the overhead percentage into line.

Each practice should set an annual production goal and then analyze the five numbers explained above on a monthly basis. It is also important to analyze the year-to-date progress on these numbers. If these five numbers are all on target, there is every reason to believe the practice will perform well if the right systems and strategies are in place. When any of these numbers underperform, it is time to analyze deeper. The beauty of these five numbers is that they are quick and easy to understand and provide an uncomplicated picture of the practice. F

“I tell fellow dentists to compare AGD’s annual dues to any other organization and to realize how much they have at their fingertips at the national, state and local levels. It’s a no-brainer.”

Partha Mukherji, DDS, FAGD Fort Worth, TX

Member since 2006

Refer your colleagues to join AGD, and you’ll both earn $50 in Referral Rewards once they join.

LEARN MORE

agd.org/member-center

The medical field has a long history of being dominated by men. Education and career opportunities in medicine and dentistry have historically been denied to women, but those barriers have been broken down over time. As of 2022, 36.7% of dentists practicing in the United States are women, according to the American Dental Association (ADA).1 And the stage is set for that number to increase significantly — the ADA Health Policy Institute reported that 56% of first-year dental students were women in 2021, the highest rate ever.2

In honor of March as Women’s History Month, AGD Impact takes a look back at how women formally broke into dentistry, the work of female pioneers over the years, and how the women in dentistry today are helping to shape the profession’s future.

“It is likely that women have been assisting with and even treating patients alongside male family members for as long as people have suffered from tooth decay,” shared Tamara Barnes, curator of the Sindecuse Museum of Dentistry at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry.

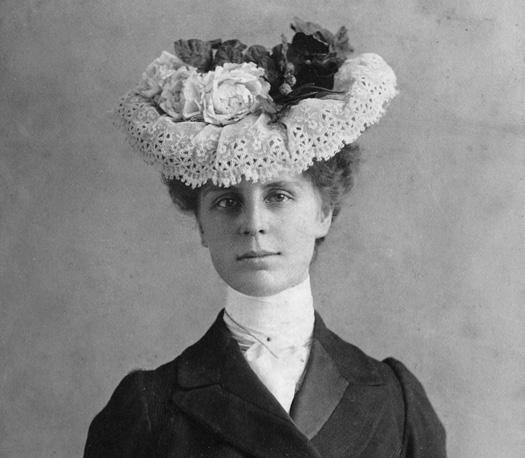

But it wasn’t until the 1800s that women began to be officially recognized in dentistry. Emeline Roberts Jones began practicing dentistry alongside her husband, Daniel Jones, in 1855. He died in 1864. She carried on his practice alone to support her two children. In 1893, the World’s Columbian Dental Congress recognized Roberts Jones as the first female dentist.3

Formal dental education and practice regulation was just getting started in the United

States in the 1800s. The first dental school, Baltimore College of Dental Surgery, opened its doors in 1840.4 It was still common for dentists to practice without going to a dental school or obtaining licensing.

Few states had practice laws when Roberts Jones took over her husband’s practice, according to Scott Swank, DDS, curator of the Dr. Samuel D. Harris National Museum of Dentistry in Baltimore. In 1841, Alabama passed the first act requiring licenses to practice dentistry, according to the American Dental Association (ADA).4 But enforcement was lax. Still, there were women seeking to gain education in dentistry.

It wasn’t until two decades later that the first woman earned a dental degree. Lucy Beaman Hobbs Taylor first attempted

to apply to medical school. After being denied, she switched her focus to dentistry. She applied to the Ohio College of Dental Surgery and received another rejection. But hers is a story of persistence.

Hobbs Taylor set up a dental practice in Iowa. She became a member of the Iowa State Dental Society, which helped her to eventually gain entrance to the Ohio College of Dental Surgery.5 In recognition of her years of practice, she completed her degree after just one year — the curriculum was two years in duration at that time, according to Swank. In 1866, Hobbs Taylor become the first woman to earn a doctor of dental surgery degree.

“Wonderfully, it was Hobbs who would teach her future husband dentistry,” Barnes adds.

Henriette Hirschfeld, born in Germany, was the first woman to complete an entire course of instruction at a dental school. She graduated from the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery in 1869. Afterward, she returned to Germany and began to practice dentistry.6

Hirschfeld faced a great deal of opposition, first in gaining acceptance to dental school and then from the male students in her classes, but she was undeterred. An article published in the Journal of the California Dental Association quoted Hirschfeld as saying, “I don’t think many of my professional brethren like it much that the females have crept into their privileges, but I can’t help the poor fellows, they will have to get used to it.”6

Ida Gray Nelson Rollins, another trailblazer in dentistry, was born in 1867. She became the first Black woman to earn a DDS in the United States. Rollins worked in dental offices while attending high school, experience that helped her to gain entrance to the University of Michigan Dental College.7 She graduated in 1890. Rollins initially practiced in Cincinnati. When she moved to Chicago with her first husband, James S. Nelson, she became the first Black dentist to practice in the city.8

The place these dentists earned in history was hard won. Women were frequently met with rejection, derision and undisguised sexism as they attempted to break into dental education and practice. For example, arguments were made that women would be undesirable dental students because of the

effect they would have on their male peers, Swank noted.

In the 1800s, male dentists also made arguments that women did not have the mental or physical capabilities required to practice. George R. Thomas, president of the Michigan Dental Association from 1872 to 1873 and 1876 to 1878, wrote that lengthy oral surgeries would “…under certain circumstances, prove very disastrous and perhaps fatal to a female operator,” according to the Sindecuse Museum of Dentistry.9

While there were plenty of vocal opponents of women in dentistry, like Thomas, there were also male dentists who advocated for welcoming women into the field. For example, James Truman, dean of the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery, publicly voiced his support for women in the field. During his 1866 commencement address, he said, “Talent is of no sex, color or clime … Let your daughters enter the professions or anything they can earn a livelihood at,” according to the Sindecuse Museum of Dentistry.9

But the prevailing attitudes of the time were difficult to change. “Although there were a handful of women entering dental schools at the turn of the century, it really was not until the 1970s that large numbers of women entered the field,” said Barnes.

Progress is rarely linear. In the early days of women’s formal entrance in the dental field, most women needed men — whether their spouses or established dentists — to advocate for them. Even as the decades passed and women were more welcomed in academic and professional spaces, they still faced challenges.

“It really wasn’t until the sexual revolution of the 1960s that women working outside of the home became an accepted cultural norm,” said Barnes. “The gains that were made during that time coincided with some setbacks, however, as the sexualization of coeds on many campuses persisted.”

Woman had been pursuing higher education for decades, but the 1960s marked a turning point with widespread gender equality movements. More women, referred to as “coeds,” opted to attend college. But they still faced challenges on campus as they joined the student bodies

of institutions with long histories of being male-dominated spaces. For example, women living in on-campus dorms were frequently subject to different rules than their male peers.10

Despite these challenges, women have carved out not only space to practice, but also to lead in dentistry. Over the decades since women were first formally recognized in dentistry, they have helped to further the profession by developing innovations in care, advocating for patients, and taking on leadership positions at academic institutions and prominent professional organizations.

Minnie Evangeline Jordon was an early pioneer in pediatric dentistry. She completed her dental education in 1898, and, by 1909, exclusively focused on the treatment of children in her practice.11

She published a book on pediatric dentistry and developed techniques to make visits to the dentist less frightening for children. Jordon was also active in organized dentistry, helping to found the Federation of American Women Dentists and the American Society of Dentistry for Children.

Arguments that women were not capable of the challenging work required by dentistry continued to crumble as women like Leonie von Zesch built their careers.

Von Zesch earned her DDS from the College of Physicians and Surgeons, San Francisco, in 1902.12 In 1906, an earthquake in San Francisco destroyed her office, but what could have been a career-ending disaster was simply the beginning of her humanitarian efforts.

Von Zesch became the first female dentist to be employed by the U.S. Army. In that role, she provided dental care at a refugee camp. Over the years, her sense of adventure led her to travel and practice. “The more remote the location, the more she found the need for services among the local populations,” said Barnes. She became the first female dentist in Alaska and spent 15 years practicing in the state. Though her career had many groundbreaking firsts, indicating social progression, her career was also not without discrimination — in 1933, she learned

of the Civilian Conservation Corps program, which was a work relief program that employed young men and teen boys for conservation-related manual labor.

Von Zesch treated more than 4,000 of the program’s workers in the rural California mountains, signing her vouchers “L. von Zesch” to avoid being detected as a female dentist. When the program authorities discovered she was a woman, she was replaced due to her gender.12

In 1958, Jeanne C. Sinkford earned her DDS from Howard University. She became dean of Howard University’s College of Dentistry in 1975, overcoming both race and gender barriers as the first (Black) woman to become the dean of a dental school. Over the course of her career, Sinkford was a trailblazer for women and minority students in dentistry. She worked with the American Dental Education Association’s Center for Equity and Diversity.13

The ADA was founded in 1859.14 AGD was founded in 1952. Decades later, Geraldine Morrow served as ADA’s first female president from 1991 to 1992.15 In 2008, Paula S. Jones, DDS, FAGD, became the first woman to lead AGD as president.16

The ADA elected its fifth female president in 2023: Linda J. Edgar, DDS, MAGD. Edgar also served as president of AGD from 2013 to 2014.

“I never really planned to be a leader, and I think that happens with a lot of leaders,” Edgar said.

She and her husband, Bryan Edgar, met in high school. He had plans to become a

dentist, and her ambition was to become an OB/GYN. Edgar taught science while her husband went through dental school. Edgar’s experience with two tubal pregnancies led to her decision not to pursue her original career plans. Instead, she continued to teach and threw herself into running. She completed 45 marathons over 10 years and started competing in Ironman competitions.

At 24, she and her husband adopted and became parents to their infant son. After she crashed her bike during an Ironman competition at age 36, her husband brought home an application for the dental school at the University of Washington.

Starting school later than many dental students made Edgar’s experience different in some respects. “I almost quit my first year because it was tough commuting from home while having a child,” she shared. “That was in 1988, and very few women were in dental school, and no one had babies.”

In a class of 54 students, 11 were women, according to Edgar. “We kind of came together as a community, which women still do now,” she said.

Despite the demands of raising a family and the rigors of her coursework, Edgar completed dental school and quickly became involved in organized dentistry. Bruce Burton, DMD, MAGD, ABGD, initially suggested she pursue leadership in dentistry.

While she had support from many colleagues, Edgar experienced firsthand the kind of doubts that still persist today. “You get those questions. ‘Are you smart enough?’

‘Are you strong enough?’ ‘Are you sure you have enough experience?’” she said.

Edgar heard these questions when she ran for AGD president and then when she ran for ADA president. “I leaned over to one of the people who asked me that question and said, ‘How many Ironmans have you done?’”

Many of the overt challenges the first women in dentistry faced have been broken down. Dental schools no longer bar women from entry on the basis of sex. Practicing dentists no longer debate whether women are capable of joining the profession. In recent years, it has not been uncommon to see graduating classes in which women outnumber men. In 2009, Vasiliki Maseli, DDS, a clinical associate professor and practice leader for the Pre-Doctoral Patient Treatment Center at Boston University Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine, graduated from dental school in Greece with a class that was two-thirds female.

Yet, challenges persist.

Women still face scrutiny and doubt, spoken or unspoken. Isabel Rambob, DDS, assistant dean for student affairs at the University of Oklahoma College of Dentistry and president of the American Association for Women Dentists (AAWD), has experienced this firsthand when performing extractions. “I have male patients, and they [ask], ‘Can you really do this?’ I

was like, ‘Well, it’s not about strength. It’s about technique,’” she explained.

Outside of the office, childcare still largely falls on the shoulders of women today, which presents challenges for women who are building their careers in dentistry and other fields. “The challenge is that, as women, we have to balance work and family at the same time,” said Maseli.

Women in dentistry also face another challenge felt by women in many other professions: an income gap. A 2023 study published in The Journal of the American Dental Association found that male dentists earn 22% more than female dentists. The study authors noted that this gap has shrunk over time, but it has become more difficult to explain. The study also noted further negative wage discrepancies, such as 24% less earnings for Black dentists and 17% less for other race non-Hispanic dentists when compared with non-Hispanic white dentists. The study also found that married dentists earned more than unmarried dentists, and dentists with three or more children earned 19% more than childless dentists.17

Woman have stepped into more leadership roles, but the majority of those positions are still held by men. “It’s not that we want to replace our male colleagues,” said Rambob. “We want to have the same opportunities. We want to share the table and be able to impact our profession as well.”

Many women have made indelible impacts on dentistry, whether their names are

“I don’t think many of my professional brethren like it much that the females have crept into their privileges, but I can’t help the poor fellows, they will have to get used to it.”

— Henriette Hirschfeld

remembered as firsts in the field or their careers were among the many others that have helped to pave the path for others to come. But work remains to be done. How can more women step into leadership roles?

“Women don’t jump into leadership often; they have to be encouraged and told that they too can do this,” said Edgar.

Women can take encouragement and inspiration from those who have come before them in many different areas of dentistry. The ADA and AGD have had female presidents, Edgar among them. Women have made strides in dental academics and research. For example, Martha Somerman, DDS, PhD, became the first woman to serve as the director of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) in 2011.18 During her nine-year tenure as director, she led new leadership efforts and championed initiatives to support other oral health researchers, like the NIDCR Director’s Postdoctoral Fellowship to Enhance Diversity in Dental, Oral, and Craniofacial Research.19

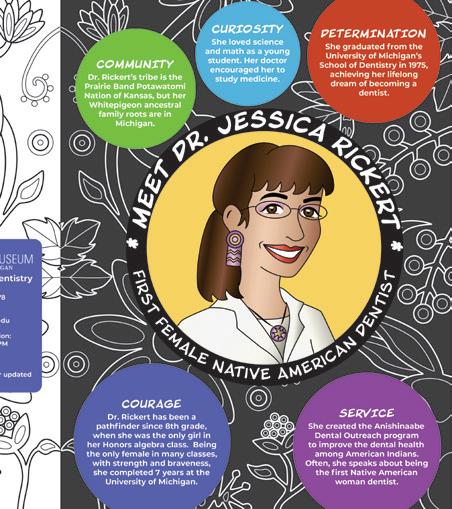

Female dentists have also made names for themselves by leading advocacy efforts in their field. Jessica Rickert, DDS, a member of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, became the first female American Indian/ Native American dentist in 1975. Rickert’s grandmother was a survivor of the U.S. American Indian boarding/residential school movement after she was forcibly removed from her family, her tribe and her culture as a child.20 In a testament to generational perseverance, Rickert broke barriers

in her career and also helped found the Society of American Indian Dentists, and she continues to work in outreach. Rickert works to connect with the Ashinaabe tribes of Michigan to promote the importance of oral health, including by working as a consultant for Delta Dental through the Ashinaabe Dental Outreach Program.21

“In an effort to inspire children to pursue dentistry as a career, Rickert worked with the Sindecuse Museum to develop a coloring booklet that could be used in pediatric clinics and disseminated to practices who serve tribal members,” Barnes shared.

Achievements in leadership are impressive, but they are rarely achieved alone. “Life is tough; be sure not to try to do it alone. Get a community,” Edgar recommended. “I could not have done what I did without developing these close relationships with women and men who have been supportive.”

Maseli is a first-generation dentist. She went to dental school in Greece before coming to the United States to complete her residency. She found that she needed to build a network from the ground up. She initially thought she wanted to enter private practice, but her experience

teaching part time during her residency led her to apply to academic positions. Over time, she has built relationships with her colleagues, students and patients. Developing these relationships can help dentists get the support they need to develop their careers.

“I think the most important advice that I would give myself 15 to 20 years ago is to create a network of mentors. Find mentors that you trust,” she said.

In addition to her work in academia, Maseli is also involved with AAWD as the director of member benefits. “By being involved with AAWD, I try to give back what I know and support other women,” she said.

The AAWD is working to launch a mentorship program in 2024 to support its student members and enhance the value of membership.

“Representation matters. Numbers matter,” said Rambob. “It is why mentorship is so important — to really elevate our profession and help young colleagues and students believe that they can do it.”

Looking to role models and building a network of mentors and peers is invaluable, but many women still struggle with comparisons. How do they compare to their male colleagues, their female colleagues? Are they good enough? Have they earned the right to pursue leadership? These questions are common enough to have earned a name: imposter syndrome.

Imposter syndrome is not exclusive to women, but research suggests they experience it significantly more often than men.22

“I have encountered so many brilliant women dentists, and they don’t see their value. They don’t think they’re good enough,” said Rambob.

While it is always worthwhile to learn more and improve, feelings of inadequacy can hold people back in their careers. Maseli urges women in dentistry to speak up. “They shouldn’t hesitate to ask for what they believe they deserve salary-wise, positionwise and benefits-wise,” she said.

Women have the opportunity to pursue leadership before their careers begin in earnest. Edgar pointed out that dental student organizations are increasingly electing women. “I’m seeing a lot of women

get elected to president [and] vice president positions, [more] than probably happened 20 years ago,” she said.

Edgar noted that there remains a lack of female representation in leadership positions with the major professional organizations, including the ADA and AGD. Of the more than 20 members of the ADA board of trustees, only four are women. Only one of the 19 current AGD trustees is a woman.

“I’d like to see that change. We have so many talented women who would bring a new perspective to any board they decide to be on,” she said. “I wish people would look at the person, not the gender, when they decide to vote for who is going to take a leadership position.”

While men do outnumber women in leadership positions in many cases, progress is being made. In 2024, Edgar isn’t the only woman leading a professional dental organization. Martha J. Mutis, DDS, MPH, is the president of the Hispanic Dental Association.23 Nicole Cheek, DDS, is the president of the National Dental Association.24

“It is going to be incredible with all these female leaders leading those dental organizations. I’m so inspired by them,” said Rambob.

With more than half of first-year dental students being female in 2021, the field is poised to welcome more women. They will have access to the opportunities that other women have helped open the door to, and they will face some of the same obstacles, too. But challenges can be overcome.

“There is no role or specialty in our profession that cannot be pursued by a woman,” said Rambob. F

Carrie Pallardy is a freelance writer and editor based in Chicago. To comment on this article, email impact@agd.org

1. “U.S. Dentist Demographic Dashboard.” American Dental Association, ada.org/resources/research/health-policy-institute/us-dentistdemographics Accessed 2 Jan. 2024.

2. Solana, Kimber. “Among First-Year Dental Students, Women See Highest Rate of Enrollment.” ADA News, 21 June 2022, adanews. ada.org/ada-news/2022/june/among-first-year-dental-studentswomen-see-highest-rate-of-enrollment/

3. “Emeline Roberts Jones.” Sindecuse Museum, sindecusemuseum. org/emeline-roberts-jones Accessed 2 Jan. 2024.

4. “History of Dentistry.” American Dental Association, ada.org/en/ resources/ada-library/dental-history Accessed 2 Jan. 2024.

5. “Lucy Beaman Hobbs Taylor.” Sindecuse Museum, sindecusemuseum.org/lucy-beaman-hobbs-taylor Accessed 2 Jan. 2024.

6. Hyson Jr., John M. “Women Dentists: The Origins.” Journal of the California Dental Association, 2002, web.archive.org/ web/20110928181315/www.cda.org/page/Library/cda_member/ pubs/journal/jour0602/hyson.html

7. “Ida Grey Nelson Rollins, DDS (First Black Woman to Graduate with a Doctorate of Dental Surgery in the USA).” Perspectives of Change, Harvard Medical School, perspectivesofchange.hms.harvard.edu/ node/122 Accessed 2 Jan. 2024.

8. “Ida Gray Nelson (Rollins).” Sindecuse Museum, sindecuse museum.org/ida-gray-nelson-rollins. Accessed 2 Jan. 2024.

9. “Women Dentists: Changing the Face of Dentistry.” Sindecuse Museum, sindecusemuseum.org/women-dentists Accessed 2 Jan. 2024. Accessed 10 Jan. 2024.

10. “150 Years of Women at Berkeley: Sexual and Political Rebellion in the Sixties.” UC Berkeley, 150w.berkeley.edu/sexual-and-politicalrebellion-sixties Accessed 10 Jan. 2024.

11. Loevy, Hannelore T., and Althea A. Kowitz. “M. Evangeline Jordon, Pioneer in Pedodontics.” Journal of the History of Dentistry, vol. 54, no. 1, 2006, pp. 3-8.

12. “Leonie von Zesch.” Sindecuse Museum, sindecusemuseum.org/ leonie-von-zesch Accessed 2 Jan. 2024.

13. “Jeanne C. Sinkford.” Sindecuse Museum, sindecusemuseum.org/ jeanne-sinkford Accessed 2 Jan. 2024.

14. “Founding of the American Dental Association.” American Dental Association, ada.org/en/resources/ada-library/dental-history/ founding-of-the-american-dental-association Accessed 2 Jan. 2024.

15. Licking, Mary. “AAWD’s Heritage: Dr. Geraldine Morrow.” American Association of Women Dentists, aawd.org/aawds-heritage-drmorrow/. Accessed 8 Jan. 2024.

16. “First Woman President of Academy of General Dentistry Installed.” Dentistry IQ, 15 Dec. 2015, dentistryiq.com/practice-management/ industry/article/16369412/first-woman-president-of-academy-ofgeneral-dentistry-installed

17. Gundavarapu, Sai Sindhura, et al. “Exploring the Impact of HouseHold, Personal, and Employment Characteristics on Dentistry’s Income Gap Between Men and Women.” The Journal of the American Dental Association, vol. 154, no. 2, 2023, pp. 159-170.E3.

18. “Martha J. Somerman, D.D.S., Ph.d., Named Director of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.” National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 6 May 2011, nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/martha-j-somerman-dds-phdnamed-director-national-institute-dental-craniofacial-research

19. “Statement on the Retirement of Dr. Martha Somerman.” National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 14 Nov. 2019, nih.gov/about-nih/who-we-are/nihdirector/statements/statement-retirement-dr-martha-somerman

20. “Meet an American Indian Dentist, Advocate, and Role Model: Jessica Rickert.” Sindecuse Museum, 2 Sept. 2021, sindecusemuseum.org/blog/jessica-rickert-dds

21. “Dental School Alumna Dr. Jessica Rickert Receives Prestigious Gies Award from ADEA.” Sindecuse Museum, 22 March 2022, news.dent.umich.edu/2022/03/22/dental-school-alumna-drjessica-rickert-receives-prestigious-gies-award-from-adea/.

22. Awinashe, Minal V., et al. “Self-Doubt Masked in Success: Identifying the Prevalence of Impostor Phenomenon Among Undergraduate Dental Students at Qassim University.” Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, vol. 18, no. 5, 2023, pp. 926-932.

23. “2024 HDA Board of Trustees.” Hispanic Dental Association, hdassoc.org/hda-board-of-trustees Accessed 2 Jan. 2024.

24. “2024 Officers & Leadership.” National Dental Association, ndaonline.org/about-nda/officers-leadership/. Accessed 8 Jan. 2024.

(Subject Code: 558)

The 10 questions for this exercise are based on information presented in the article, “The History of Women in Dentistry” by Carrie Pallardy on pages 10–14. This exercise was developed by members of the AGD editorial team.

1. As of 2022, _____% of dentists practicing in the United States were women, according to the American Dental Association (ADA). The ADA Health Policy Institute reported that a total _____% of first-year dental students were women in 2021, the highest rate ever.

A. 16.7; 36

B. 26.7; 46

C. 36.7; 56

D. 46.7; 66

2. Emeline Roberts Jones began practicing dentistry alongside her husband, Daniel Jones, in _____, before carrying on his practice alone after his death in 1864. In 1893, the World’s Columbian Dental Congress recognized Roberts Jones as the first female dentist.

A. 1855

B. 1856

C. 1857

D. 1858

3. In 1866, Lucy Beaman Hobbs Taylor become the first woman to earn a doctor of dental surgery degree when she graduated from the _____.

A. Baltimore College of Dental Surgery

B. New York College of Dentistry

C. Philadelphia College of Dental Surgery

D. Ohio College of Dental Surgery

Reading the article and successfully completing the exercise will enable you to:

• recognize the ways female dentists have impacted the history of the profession;

• understand the obstacles female dentists have overcome in the past; and

• recognize the barriers female dentists continue to face today.

Answers for this exercise must be received by Feb. 28, 2025.

4. Henriette Hirschfeld became the first woman to complete an entire course of instruction at a dental school when she graduated from the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery in _____.

A. 1867

B. 1868

C. 1869

D. 1870

5. Ida Gray Nelson Rollins, the first Black woman to earn a DDS in the United States, graduated from the University of Michigan Dental College in _____.

A. 1890

B. 1891

C. 1892

D. 1893

6. The ADA was founded in 1859 and elected its first female president in _____; AGD was founded in 1952 and elected its first female president in _____.

A. 1976; 1993

B. 1981; 1998

C. 1986; 2003

D. 1991; 2008

7. Linda J. Edgar, DDS, MAGD, 2023–2024 ADA president, is the organization’s _____ female president.

A. fourth

B. fifth

C. sixth

D. seventh

8. A 2023 study published in The Journal of the American Dental Association found that male dentists earn _____% more than female dentists.

A. 12

B. 17

C. 22

D. 27

9. Jessica Rickert, DDS, who became the first female American Indian/Native American dentist in 1975, is a member of which Native American tribe?

A. Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians

B. Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation

C. Navajo Nation

D. Blackfeet Nation

10. On their 2023–2024 boards of trustees, ADA has _____ female trustee(s), and AGD has _____ female trustee(s).

A. four; one

B. three; two

C. two; three

D. one; four

Noncompete clauses appear in both the hiring documents of dental office staff and in the contracts dentists have with their own employers. Many dentists have mixed feelings about noncompetes. Dentists don’t want employees opening new practices down the street, taking patients with them, and even feel betrayed when staff members in whom they have invested time and training later decide to leave. At the same time, dentists themselves don’t want to sign noncompetes that limit their ability to open their own practices later in their careers.

While advising dentists on staff member contracts, I am frequently asked how much limitation can be placed on a new employee. Then, when dentists look at their own employment contracts, I hear, “They can’t do that, can they?” Underlying these questions is little understanding of noncompete clauses among dentists and confusion about the difference between competition and solicitation — two different clauses with overlapping goals and terms. In this article, I hope to bring clarity to the issues presented by years of boilerplate contracts designed to restrict employees when they leave a dental practice.

Understanding noncompete clauses is all the more important now, as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has proposed a rule

change that would effectively ban all noncompete clauses both in new and existing contracts.1 While a final vote on the FTC rule is not expected until April 2024, and legal challenges are expected that will delay — if not prevent — the rule from going into effect,2 this nonetheless reflects a nationwide state legislative movement to ban noncompete clauses.

As of the end of 2023, three states (California, North Dakota and Oklahoma) and the District of Columbia ban noncompete clauses in employee agreements; nine more states (Colorado, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, New Hampshire, Oregon, Rhode Island, Virginia and Washington) ban noncompete clauses for workers earning below a certain wage level; and three more states (Connecticut, Massachusetts and New Hampshire) limit the time length of noncompete clauses. In addition, on May 30, 2023, the General Counsel of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) sent a memorandum to all regional directors advising them that:

It is unlikely an employer’s justification would be considered reasonable in common situations where overbroad non-compete provisions are imposed on low-wage or middle-wage workers who lack access to trade secrets or other protectible interests, or in states where noncompete provisions are unenforceable.3

“Nonsolicitation clauses are more narrowly focused than noncompete clauses, as they specifically target the act of soliciting and do not necessarily prevent the employee or business partner from working in a competing business.”

Whether all noncompete clauses will be banned at either the state or federal levels is unknown, but it is clear noncompete clauses are being examined closely when challenged by courts and increasingly found unenforceable.

A noncompete clause is a contractual agreement in which one party agrees not to compete with another party, usually within a specified time and geographic area. However, the noncompete agreement cannot wholly prevent an employee from working in their profession. Courts often assess the reasonableness of noncompete clauses and find restrictions to be unenforceable if they are too broad or unreasonable. Courts also consider whether the restrictions are narrowly tailored to protect a legitimate business interest without imposing undue hardship on the employee. Legitimate business interests include trade secrets, confidential information, customer relationships or unique skills that the employer has invested in developing.

The key elements of a noncompete clause are:

• Duration: The length of time during which competition is prohibited. A restriction for more than a year is unlikely to be considered reasonable.

• Geographic scope: The geographic area within which the restricted party is prohibited from competing. Courts may be hesitant to enforce clauses that restrict employees from working in a wide geographic area, especially if it goes beyond the area where the employer does business. For example, “within one mile” in a sparsely populated area is more likely to be considered reasonable than the same distance in a densely populated city.

• Scope of activities: The specific activities or industries that are restricted — for example, “the practice of dentistry” or

“implant dentistry.” This could also include working for a direct competitor, starting a similar business, or soliciting clients or employees from the former employer.

• Consideration: In many jurisdictions, for a noncompete clause to be enforceable, the restricted party must receive some form of consideration (benefit) in exchange for agreeing to the restrictions. This consideration could be a job offer, special training, access to proprietary information or some other tangible benefit.

Most employment contracts have both noncompete and nonsolicitation clauses, and it is critical to know the difference (see “Differences Between Noncompete and Nonsolicitation Clauses” on the following page).

A nonsolicitation clause is a contractual provision often found in employment agreements, partnership agreements or business contracts. This clause restricts one party (typically an employee or a business partner) from actively seeking or enticing clients, customers, employees or other business relationships away from the other party. Like a noncompete clause, the primary purpose of a nonsolicitation clause is to protect the legitimate business interests of the employer.

The key elements typically found in a nonsolicitation clause include:

• Patients: The clause may prohibit the solicitation of clients or customers with whom the employee or business partner had a business relationship during their tenure with the company.

• Employees: It may restrict the solicitation of employees to prevent the departing employee from recruiting current employees to join them in a new venture or with a different employer. However, a current employee cannot be prevented from joining a departing employee of their own accord.

• Business relationships: In some cases, the nonsolicitation clause may extend to other business relationships, suppliers or contractors.

• Duration: Similar to noncompete clauses, nonsolicitation clauses have a specified duration of time during which the restrictions apply.

• Geographic scope: Like a noncompete clause, the geographic scope of the nonsolicitation clause defines the geographical area within which the departing employee is restricted from soliciting clients, employees or business relationships.

Noncompete Clause Nonsolicitation Clause

A contractual agreement in which one party agrees not to compete with another party, usually within a specified time and geographic area.

Key elements:

• Consideration

• Duration

• Geographic Scope

• Scope of Activities

Restricts one party (typically an employee or a business partner) from actively seeking or enticing clients, customers, employees or other business relationships away from the other party.

Key elements:

• Business Relationships

• Duration

• Employees

• Geographic Scope

• Patients

“While dentists do not own their patients, protecting assets like proprietary information is a legitimate business interest, and patient lists are proprietary.”

Nonsolicitation clauses are more narrowly focused than noncompete clauses, as they specifically target the act of soliciting and do not necessarily prevent the employee or business partner from working in a competing business. However, clearly there is overlap between nonsolicitation and noncompete clauses. Noncompete agreements and nonsolicitation agreements are both types of restrictive covenants used in contracts to protect a company’s interests. However, they have different focuses and restrictions.

The key differences between noncompete agreements and nonsolicitation agreements are:

• Focus of restriction: Noncompete agreements focus on preventing direct competition, while nonsolicitation agreements focus on preserving relationships with clients, customers and employees.

• Scope of restrictions: Noncompete agreements generally have broader restrictions on engaging in competitive activities, while nonsolicitation agreements are more narrowly focused on specific solicitation activities, like contacting patients or current employees directly.

• Nature of protection: Noncompete agreements aim to protect the company from direct competition, while nonsolicitation agreements aim to protect specific relationships and prevent the solicitation of clients, customers or employees.

It’s not uncommon for contracts to include both noncompete and nonsolicitation clauses, each serving a distinct purpose in safeguarding the interests of the employer. The enforceability of these agreements depends on various factors, including the state law, the specific language of the clauses, and their reasonableness in scope and duration.

Much of the FTC’s argument for its proposed rule is in fact focused on nonsolicitation. The FTC argues that noncompete clauses forbidding the solicitation of other employees to leave the employer violate the regulatory right of workers to organize and seek better employment. This further confuses the distinction between a noncompete clause and a nonsolicitation clause. A noncompete clause is generally directed at the future employment of the bound worker; a nonsolicitation clause generally limits contacting clients of the employer and luring the clients away. Remember that clients and patients are free to change dentists, but the former employee bound by a nonsolicitation agreement cannot reach out to the patient first.

Regardless of the fate of the FTC’s proposed rule, it is clear that state legislatures are limiting the enforceability of noncompete agreements. For dentists who are either bound by noncompete agreements or considering binding an employee to one, first be sure you know what your state law requires. If the state law does not set clear limits on an enforceable noncompete agreement, consider whether such an agreement can be justified by a legitimate business interest, such as protecting trade secrets or proprietary business information or practices. Employees come and go, and there has been a shortage of workers post-COVID-19 pandemic, when so many healthcare workers left the profession. But, as competition for workers has increased, so has the need to increase wages in order to retain them. Consider whether retaining employees can be done by improving work life rather than using threats that restrict future work.

In the dental practice context, noncompete agreements with employee dentists are likely to be drafted to prevent the employee from opening a practice nearby and drawing away the employer’s patients. The growing disfavor for noncompete agreements makes it particularly important that the duration be no more than a year or perhaps two, the scope of activity be precisely that which mimics the employer’s business, and the geographic scope not prevent the employee from working or opening a practice in the same community.

“For dentists who are either bound by noncompete agreements or considering binding an employee to one, first be sure you know what your state law requires.”

Dentists should also draw a clear distinction between a noncompete clause and a nonsolicitation clause. If the goal is to keep a former employee from taking patients, a nonsolicitation clause is a better option. While dentists do not own their patients, protecting assets like proprietary information is a legitimate business interest, and patient lists are proprietary. A nonsolicitation clause can be drafted to forbid a former employee from taking proprietary information, such as trade secrets, patient lists and employee contact information. In addition, patient lists, employee contact information and office business practices may meet the definition of “trade secrets” in the Uniform Trade Secrets Act:

[I]nformation, including a formula, pattern, compilation, program device, method, technique, or process, that: (i) derives independent economic value, actual or potential, from not being generally known to, and not being readily ascertainable by proper means by, other persons who can obtain economic value from its disclosure or use, and (ii) is the subject of efforts that are reasonable under the circumstances to maintain its secrecy.4

As of the end of 2023, the Uniform Trade Secrets Act regulating improper use or disclosure of a trade secret has been adopted by every U.S. state except New York and North Carolina. Locate the Trade Secrets Act in your state, and see what the penalties are for violating it. In Nevada, for example, violation of the Uniform Trade Secrets Act is “a category C felony and shall be punished by imprisonment in the state prison for a minimum term of not less than 1 year and a maximum term of not more than 10 years and may be further punished by a fine of not more than $10,000.”5 This illustrates how state law protections may accomplish the same goals as a nonsolicitation clause with the addition of criminal penalties.

In sum, including a noncompete clause in an employment agreement requires knowing your state law. If state law allows noncompete provisions, it must be narrow and reasonable. Nonsolicitation agreements should avoid any language that references competition and instead focus narrowly on a former

employee taking proprietary information from the employer’s practice and using that information to cause economic harm. Don’t use boilerplate language. Don’t print an agreement off the internet. Don’t use the employment agreement you have always used. Rather, use your lawyer to craft an agreement that both meets state law requirements and furthers the legitimate business interests of your practice. F

Jake Kathleen Marcus, JD, has been a regulatory lawyer primarily in the healthcare space for over 30 years. They are currently Director of Legal at Nurse-Family Partnership as well as a student at Queen Mary University of London working on an LLM in technology, media and telecommunications. To comment on this article, email impact@agd.org

1. “Non-Compete Clause Rule.” Federal Trade Commission, 19 Jan. 2023, federalregister.gov/ documents/2023/01/19/2023-00414/non-compete-clause-rule. 88 FR 3482.

2. Kishman, Will. “The Non-Compete Landscape in 2023: What Employers Should Know About Changes in Non-Compete Law from the FTC, NLRB, Antitrust Claims and New State Laws (US).” Employment Law Worldview, 28 Sept. 2023, employmentlawworldview.com/the-non-compete-landscape-in-2023-what-employers-should-know-about-changes-in-non-compete-law-from-the-ftc-nlrb-antitrust-claims-and-new-state-lawsus/.

3. Abruzzo, Jennifer A. “Memorandum GC 23-08: Non-Compete Agreements that Violate the National Labor Relations Act.” Office of the General Counsel, National Labor Relations Board, 30 May 2023, nlrb.gov/ guidance/memos-research/general-counsel-memos.

4. “Trade Secret.” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, law.cornell.edu/wex/trade_secret. Accessed 9 Jan. 2024.

5. “Nevada Revised Statutes: Chapter 600A — Trade Secrets (Uniform Act).” Nevada Legislature: The People’s Branch of Government, leg.state.nv.us/nrs/nrs-600a.html. Accessed 9 Jan. 2024.

Exercise No. IM153, 1 CE Credit

(Subject Code: 550)

The 10 questions for this exercise are based on information presented in the article, “The Dentist’s Guide to Noncompete Clauses” by Jake Kathleen Marcus, JD, on pages 16–19. This exercise was developed by members of the AGD editorial team.

1. As of 2023, all of the following states and the District of Columbia ban noncompete clauses in employee agreements entirely except one. Which is the exception?

A. California

B. Alabama

C. Oklahoma

D. North Dakota

2. As of the end of 2023, all of the following states limit the time length of noncompete clauses except one. Which is the exception?

A. New Hampshire

B. Connecticut

C. Massachusetts

D. Vermont

3. The acronym NLRB stands for National Labor _____ Board.

A. Regulatory

B. Reform

C. Relations

D. Rulemaking

4. On May 30, 2023, the General Counsel of the NLRB sent a memorandum to all Federal Trade Commission regional directors advising them that “It is unlikely an employer’s justification would be considered _____ in common situations where overbroad non-compete provisions are imposed on low-wage or middle-wage workers who lack access to trade secrets or other protectible interests…”

A. legal

B. ethical

C. enforceable

D. reasonable

Reading the article and successfully completing the exercise will enable you to:

• understand the key elements of both noncompete and nonsolicitation clauses;

• identify the differences between noncompete and nonsolicitation clauses; and

• understand the effects of pending regulatory changes.

This exercise can be purchased and answers submitted online at agd.org/self-instruction Answers for this exercise must be received by Feb. 28, 2025.

5. The key elements of a noncompete clause are duration, geographic scope, consideration and _____.

A. licensing

B. advertising

C. scope of activities

D. continuing education

6. Which of the following definitions accurately describes the term “consideration” in regard to a noncompete clause?

A. The language of the clause must take into account the restricted party’s ability to continue in the profession afterward.

B. The restricted party must receive some form of benefit in exchange for agreeing to the restrictions.

C. All parts of the noncompete clause must be deemed reasonable in order to be enforceable.

D. The employer and the restricted party must have an established business relationship to a certain degree in order to warrant the existence of a noncompete clause.

7. A nonsolicitation clause restricts one party (typically an employee or a business partner) from actively seeking or enticing clients, customers, employees or other business relationships away from the other party. A disgruntled dental hygienist who quits and follows a former associate dentist to a new practice is an example of solicitation on the former associate dentist’s part.

A. Both statements are true.

B. The first statement is true; the second is false.

C. The first statement is false; the second is true.

D. Both statements are false.

8. The key elements typically found in a nonsolicitation clause include all of the following except one. Which is the exception?

A. geographic scope

B. professional skills

C. business relationships

D. patients and employees

9. As of 2023, the Uniform Trade Secrets Act has been adopted by every U.S. state except _____.

A. Illinois and Idaho

B. Ohio and Oklahoma

C. Maryland and Massachusetts

D. New York and North Carolina

10. In Nevada, violation of the Uniform Trade Secrets Act is a _____.

A. category C felony

B. category D felony

C. gross misdemeanor

D. misdemeanor

• AGD Supply Discount: Automatically access your membership’s savings benefit of up to 30% off standard industry retail.

• Authorized Access: Order with confidence! No gray market. No fraudulent products.

• FREE Shipping: Consolidate your supply sources and eliminate shipping fees within the continental United States.

• Save Time: Order all of your dental supplies from one easy-to-use online dental supply store.

• Support: Our dedicated account managers review every order for accuracy and apply qualifying manufacturer discounts and deals.

This summer, AGD heads to the City of Lakes for its annual scientific session, the premier meeting for general dentistry. More than 2,500 general dentists will take over the Minneapolis Convention Center for a weekend full of camaraderie and networking, exhibits on the latest products and technology, and — of course — high-quality continuing education (CE) specifically tailored to general dentists. But this year’s scientific session host city promises something extra: It’s a pictureperfect American destination. Learn more about what AGD2024 and Minneapolis have to offer you, and plan your trip now so you can find out why Rock and Roll Hall of Famer Prince said, “I like Hollywood. I just like Minneapolis a little bit better.”

From advanced hands-on education to clinical and practice management lectures in an innovative one-hour lecture format, AGD’s annual scientific session has earned a reputation for having some of the finest dental CE in the world. How do you cater CE to general dentists? You put out a buffet of everything! Attendees can take courses on a wide range of topics, including endodontics, periodontics, prosthodontics, implantology, oral pathology, and esthetic and restorative dentistry. Attendees can also balance out their course lists with a healthy serving of practice management courses designed to help dentists take their practices to new economic heights with the latest business best practices — the perfect complement after learning new skills and techniques. Formats include both lecture and hands-on participation, so attendees can take home a wealth of new information and gain hands-on experience that will enable them to put new skills into action the following Monday morning.

This year, AGD is launching a new series of 45-minute lectures (35 minutes of presentation, 10 minutes of Q&A). Formerly known as Dental Pearls and Emerging Speakers, the Take the Floor lecture series

• Network with more than 2,500 fellow dentists and AGD members.

• Earn more than 54 CE credits.

• Take part in interactive participation courses.

• Learn current best practices from industry thought leaders.

• Attend free New Dentist Lounge lectures.

• Expand your knowledge with cutting-edge Learning Lab presentations.

will feature subject matter experts presenting on timely topics in dentistry. These symposium-style presentations will allow speakers to highlight themes across clinical disciplines, mental health and physical wellbeing. Participants will gain critical insights into today’s most pressing challenges and walk away with an invaluable educational experience. These short, niche lectures are the perfect way to round out your educational experience while at AGD2024.

Celebrate AGD’s newest class of Fellows, Masters and Lifelong Learning and Service Recognition recipients at the AGD2024 Convocation Ceremony at the Minneapolis Convention Center, Saturday, July 20. This formal graduation ceremony pulls out all the stops to recognize the brightest general dentists in the country as their dedication to lifelong learning and service to the profession and their communities culminates in these prestigious awards. Show your support for your colleagues, and gain inspiration from the pomp and circumstance. Following the Convocation Ceremony, join AGD leaders and members, along with families and friends, for an entertaining reception celebrating this year’s recipients.

Calling all students, residents and new grads! If you are a student enrolled in dental school or a residency program, or a new dentist who graduated within the last five

years, AGD2024 has extra benefits tailored to your needs.

The New Dentist Lounge provides students, residents and new graduates with a dedicated space to connect, learn and grow. Highlights of the lounge include:

• Dedicated free CE sessions.

• Collaborative workshops.

• Mentorship events.

• Networking opportunities.

Find the full list of New Dentist Lounge courses and speakers at agd2024.org. All New Dentist Lounge courses are free and represent AGD’s investment in your future.

With its gorgeous lakes, expansive park system, thriving arts scene, plentiful shopping and great food, Minneapolis offers a beautiful backdrop for AGD2024 and a great destination, whether you plan on bringing guests or traveling solo. A full list of activities in and around the city can be found at minneapolis.org, but here is a list of AGD’s top picks.

Just a one-mile walk from the Minneapolis Convention Center, the Stone Arch Bridge is one of Minneapolis’ most iconic sites and, on the other end of the bridge, you’ll find St. Anthony Main. This hidden gem is the oldest part of the city and is characterized by its cobblestone road lined with historic buildings. Take a stroll down to Water

Power Park and find a gorgeous view of the Mississippi River and St. Anthony Falls with a striking backdrop of the city skyline.

In Minneapolis, you are never more than six blocks from a park, so you never feel like you’re in a concrete jungle. With over 22 lakes in Minneapolis alone, there is a rich lake culture that will make you get outdoors, stay healthy and be continuously struck by the beauty of nature. The main attraction? The Chain of Lakes: five of the largest lakes in Minneapolis. Rent a canoe or kayak and travel across all five, or stroll or bike along the roughly 15 miles of paved shoreline paths. The 15 miles of shoreline also mean you’re sure to find a spot to set up and lounge by the water if strenuous activity isn’t your thing or you’re just taking a break. Just a 13-minute drive from the Minneapolis Convention Center you can visit a striking wilderness waterfall in an urban setting at Minnehaha Falls.

For the culturally minded, get hands-on with science at the Science Museum of Minnesota, view one of the finest and most extensive art collections in the country at