Seeing differently

Speculative thoughts about the nature of seeing

‘

To know the spirit of a place is to realise that you are a part of a part and that the whole is made of parts, each of which is a whole. You start with the part you are whole in.’

You start in the part you are a whole in, but you don’t finish there. Your whole becomes bigger as it takes in other parts of further wholes. It becomes part of a bigger whole.And so you continue to grow in a fashion that echoes ideas shaped by that under-appreciated philosopher, Alfred North Whitehead, in ‘Process and Reality’.

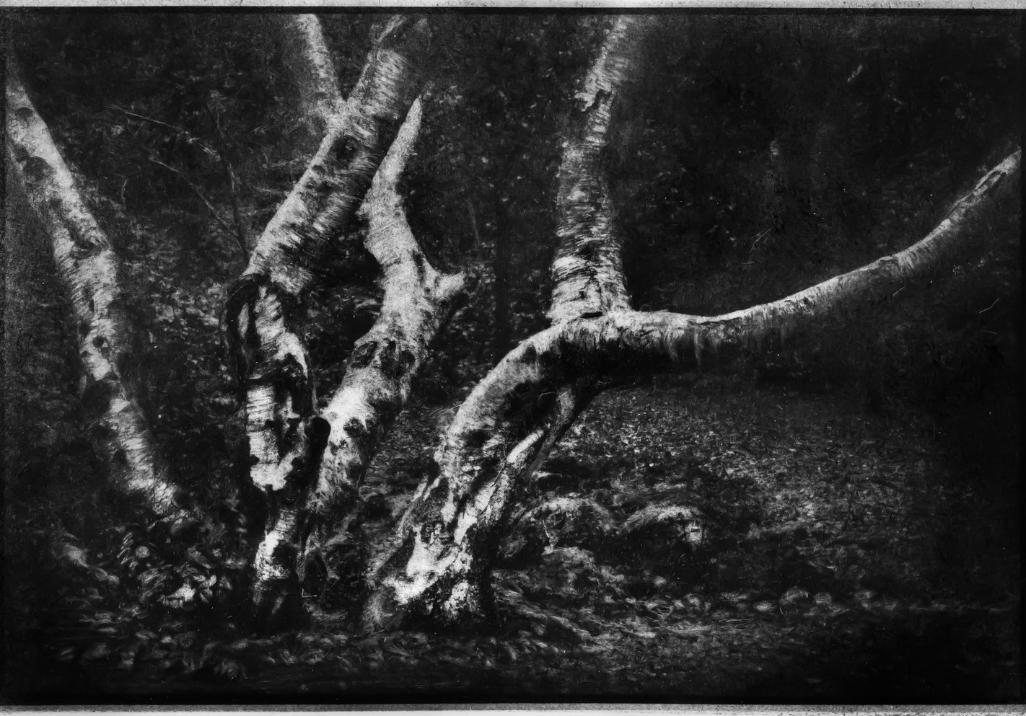

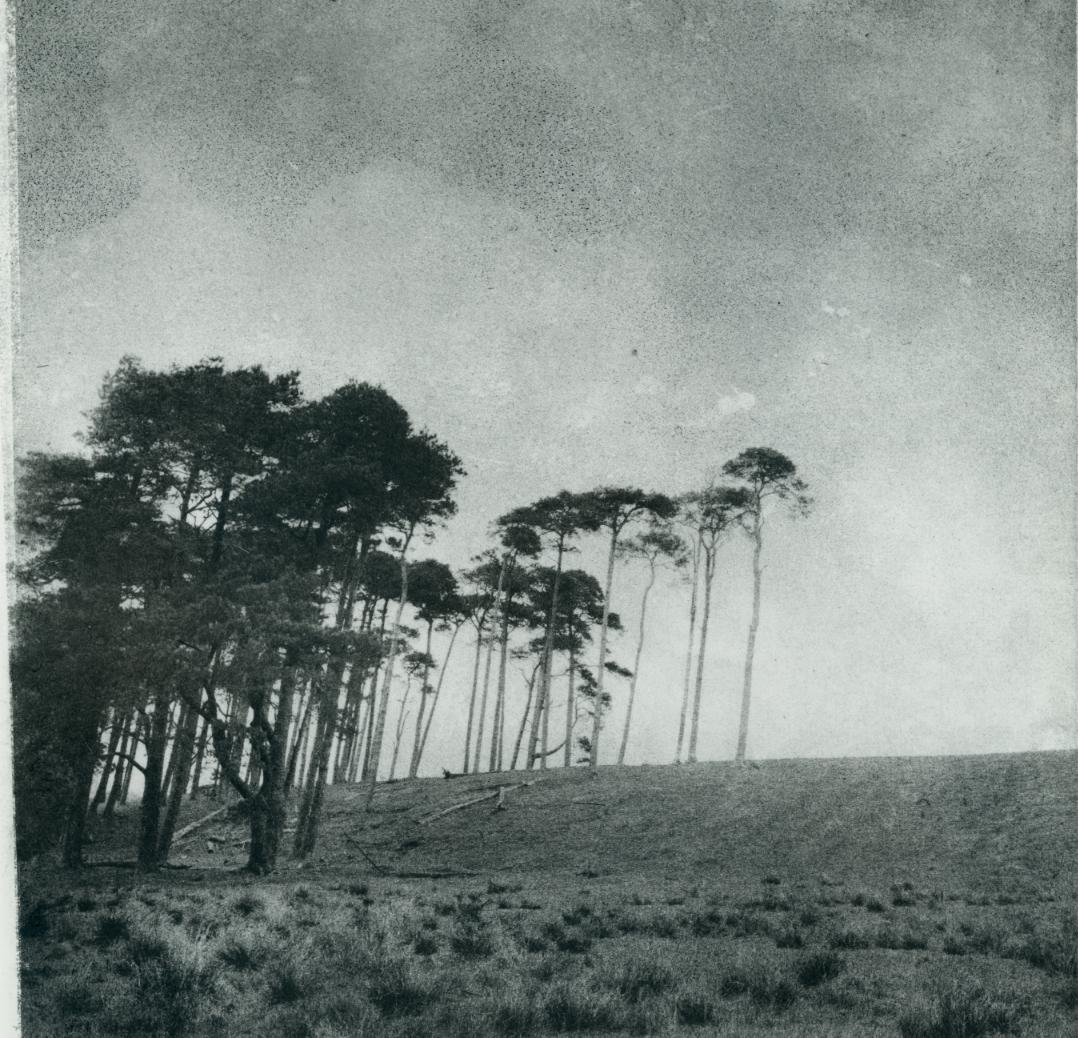

What if … What if you could capture moods in photographs such that the actual image was just a way of conveying mood, rather than being the purpose of a photograph? Rather than taking photo-graphs we could be taking mood-graphs.

I want to discuss the idea that, as photographers, we have the opportunity, afforded precisely by what we do, to cultivate a way of seeing differently. How differently? The aim would be to capture something felt rather than seen. Photography, like anthropology, is about looking at and, crucially for this argument, seeing through. Seeing through is very hard, as it’s the last thing we learn.

Gary Snyder (2010), ‘The Practice of the Wild’, Counterpoint Press edition p.41

To get the ball rolling let me introduce two concepts: ‘attending-tosomething’and ‘spatially extended moods’. Let’s start with ‘attendingto-something’as without that, there is nothing.

Attending to something

In order to attune oneself to a space (to be defined later), one has to ‘attend’to it, that is, you have to give it total attention. Can we give something ‘total’attention? I think it’s difficult because it means dropping the notion of ‘self’, but possible with practice.

Here, I speak of attention in a particular way. It is best described by Simone Weil. For Weil, attention is not merely a cognitive faculty but the rarest and purest form of generosity. Rather than active concentration or wilful focus (‘to attend’is a verb and therefore conjures an active tense, which is not what we need here), she describes attention as a form of receptive waiting, which for her, when taken to its ultimate degree, is a form of prayer.

So central to her philosophy was the concept of attention. This faculty formed the real object and almost the sole interest of academic studies.

For her, studying was about learning how to be attentive in her sense of the word. I tend to agree.

Let’s extend this idea to photography. The real object of photography is to practise attending to things. In doing that, we capture spaces (I’ll get on to that in a while). Key aspects of Weil’s attending include: patiently waiting and receiving, rather than grasping; focussing on process rather than results; emptying the ego (unselfing); looking outwards not inwards; approaching the practice of attention with joy.

Let me turn to the second concept – ‘spatially extended moods’.

Spatially extended moods

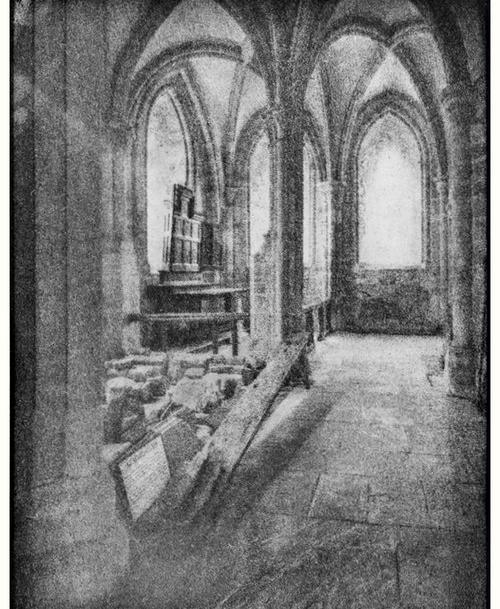

Imagine entering an old church.

We might feel the need to walk slowly and quietly. Imagine walking through a forest at night. We might feel anxious, or we might feel exhilarated. What we feel is not straight-forwardly a read off from how a forest at night is. What we feel is a product of that forest and our personal history.

Places have atmospheres.

Representations induce moods. One only need look at the photographs of Todd Hido say, or Moriyama or Brassaï to know that pictures convey moods.

But let’s take this further. Perhaps spaces have moods. Literally. There is hinterland to this idea even though part of me thinks it a bit outlandish.

We can point to Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Bachelard and Böhme for whom moods form part of extended space, providing structure to our experiences.

In ‘The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge’, Rainer Maria Rilke doesn’t just describe places as metaphorically emotional - he writes about them as physically suffused with feeling.

Georg Trakl, the Symbolist-Austrian poet, thought of spaces as inherently melancholic or haunted. His poems are full of hallways, courtyards, and empty houses that radiate despair, decay, or silence - as objective qualities of space, not just inner mental happenings.

Emily Brontë in ‘Wuthering Heights’, T.S. Eliot in ‘The Waste Land’ and ‘Four Quartets’- I could go on listing examples.

I imagine myself on an empty Dakotan plain looking across an old rusting Chevrolet truck. The flat emptiness of the terrain with its abandoned farms and machinery bears witness to past hard times. There is an atmosphere. My feeling is a response to things out in the environment, to this atmosphere – it’s not reducible to a private emotion. The scene has a mood; it’s not just in me. It’s between the scene and me, somehow.At least that’s how it seems to me.

How might such a thing be? It could go like this:

The space in which I am, is not an objective thing. Nor is it a subjective thing. It’s the result of perception, memory and place interacting, each affecting the other. It’s a ‘between’thing.

My space is different to yours, even were you able to occupy the same place as me, which of course you can’t as I’m different to you.

The spaces around us have ‘moods’. That is because our spaces are, in a way, human constructs. Moods, being qualities of spaces, are neither objective nor subjective.

We become conscious of moods when we feel their effects. Moods need not be consciously experienced. However, they continue to influence thought, perception and behaviour. They form the background to how we structure our experiences. Moods influence what we

choose to look at and how we see.Although diffuse, they are conveyable.

Let me now put the two aspects, attending-to-something and spatially extended moods, together.

Seeing differently

In the forgoing I describe Simone Weil’s idea of attention and the idea that spaces are essentially part of us, human constructs, and are infused with moods – ‘spatially extended moods’. The spaces that we make for ourselves are the entering points from the part we are a whole of, ‘selves’(being social constructs), to the parts of other wholes. I know that sounds cryptic but it’s simple if we not only think of ourselves as

substance entities, that is ‘selves’, but also processes, that is parts of more extensive wholes.

Let me re-iterate the Snyder quote:

‘To know the spirit of a place is to realise that you are a part of a part and that the whole is made of parts, each of which is a whole. You start with the part you are whole in.’

It may be though that you need to dwell on this a little in order to fully appreciate it.

I want to borrow some ideas sparked from reading Rainer Maria Rilke’s ‘The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge’. I didn’t know his work, but I found this book very interesting.

For Rilke, conventional seeing is superficial and filtered through social expectations, habits, and preconceptions. We see what we expect to see, what we're comfortable seeing, or what serves our immediate needs.

This kind of seeing is important. I would say, coming from an evolutionary biology educational background, that this instrumental way of seeing has evolved to recognise emerging risk. It allows us to navigate daily life and societal norms. But perhaps it provides a barrier to looking at things differently?

Learning to see differently, by contrast, involves bracketing off this instrumental way of seeing. It involves stripping away the protective layers of familiarity, those that are based on what has worked for us as a species in the context of survival logic.

Malte, the character in the Rilke novel, painfully experiences a way of seeing throughout the novel - he becomes overwhelmed by the rawness of Parisian street life, by the faces of the dying in hospitals, by the smell of poverty and decay. What others might dismiss or ignore, Malte

absorbs with disturbing intensity.Abeggar's outstretched hand becomes not just a social problem but a revelation of human vulnerability and need.

Here we get to it. This way of seeing requires a willingness to remain open to experiences that might be overwhelming or disturbing. This willingness to be open is akin to Weil’s receptive attention.

The process is about attuning to the mood of your space. This type of seeing may not be comfortable. It requires a vulnerability that stems from being truly open to reality's difficulties and beauty. It requires one to be self-less.

My nominalist tendencies make it difficult for me to swallow such an idea. But as a photographer, it’s something I would want to endorse.

Tony Cearns is a photographer and postgraduate Philosophy research student. He can be reached via his substack site @tonycearnsphotography.