Tony Cearns

Personal reflections on a style of photography

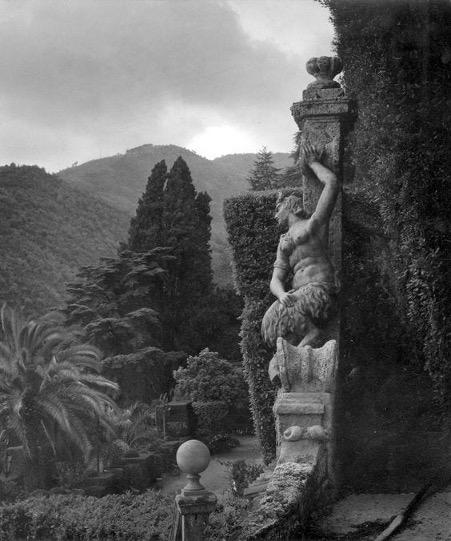

I’m very drawn to Edwin Smith’s1 photograph taken at the Villa Garzoni in Collodi, Tuscany. It’s not the super-vibrant garden photograph that we are used to seeing from the likes of the Chelsea Flower Show. But there again, those are not real gardens, just pretences.And black and white “re-introduces ‘intelligence’into photography at nearly every step”, as Smith was to go on to say.

I think the reclining figure is the goddess Ceres. There is little doubt that Smith would have photographed the other statues in the garden, Neptune,Apollo, Bacchus, and Daphne, but I can find no evidence for that. But I assume that he must have.

Edwin Smith was an architectural photographer steeped in the understanding of line, surface and perspective, meticulous in his approach with an old large

format camera, and well known for re-visiting locations to see how things continued to look.

Smith had a good eye. The subtleties of light, texture, and particularly composition provide a felt sense of place, a recognition of something otherworldly, gothic, if you permit me to use that word. I do so deliberately.

Today the word ‘gothic’suggests the dark, mysterious, or romantically macabre. The word has evolved from meaning a tribal designation (Goths and Visigoths) to an architectural style through a literary genre to a present-day cultural sensibility, best seen in the English town of Whitby at certain times of the year. But there is more to it than this. Gothic architecture had a populist dimension. Gothic cathedrals were community projects that involved entire towns over generations. The Baroque, however, emerging in the 17th century, was associated with absolute monarchy and aristocratic power. Its overwhelming ornamentation, theatrical effects, and complex symbolism were designed to inspire awe and reinforce hierarchy.

As I gaze on Edwin Smith’s photographs, some thoughts and feelings (are they different things?) come to mind.Asense of timelessness and melancholy, always a draw for me. The idealised forms of sculptures pointing to a human presence in virtue of its absence. The idea of solitude and stillness bringing about a calm detachment (or is it nostalgia?). The formal composition pitting static against organic forms, reminding me of Piranesi's etchings of decaying Roman architecture.

There is a sense of a drama being played out, the inexorable growth of wilderness overtaking the artifactual nod to civilisation. ‘Co-operating with the inevitable’is how Olive Cook, writer and historian and Edwin Smith’s partner, described his photography. Much the same can be said about the tending of gardens.

As a gardener, I realise the inevitability of my garden’s eventual demise to the forces of nature. I too plant small sculptures, earthenware pots and shapely rocks in and among my vegetables.

Gardens remind me of the contingency of human existence. They must be given room to be within their nature if they are to occupy that narrow space between culture and wilderness. If left to their own urges, they cease to be gardens. Coercion within a structure, a harnessing, describes well what we gardeners do. Left to flourish, gardens lose their garden way of being, becoming less intimate, too wild to comprehend and take in, in one go.

Their success is based on a tension between order and chaos. Something of the wild must be allowed to remain. I only partly agree with EmmaCrichton Miller’s observation 2, ‘A garden I love must be wild’. If it was totally wild, it would cease to be a garden dispelling the chance ‘to fashion an entire kingdom to suit … (an) unfettered fancy’.

Garden forms range widely. The wet moss gardens of Kyoto, the lush orchid jungle gardens of Singapore, the ‘floribundance’of Vita Sackville-West’s Sissinghurst, the beach sparseness of Derek Jarman’s Dungeness Prospect Cottage, all serve to feed a type of hunger. Emma Crichton Miller again: “a place for discovering the dark and the strange, the ‘not-I’ that must become the ‘also-I’”.

Such a realisation may have struck the likes of many garden photographers in their time, Paddy Summerfield, Siân Davey, Vanessa Winship, Jem Southam, Lynn Geesaman and others, although I struggle sometimes to find it. The same cannot be said for the garden photography of Beth Dow.

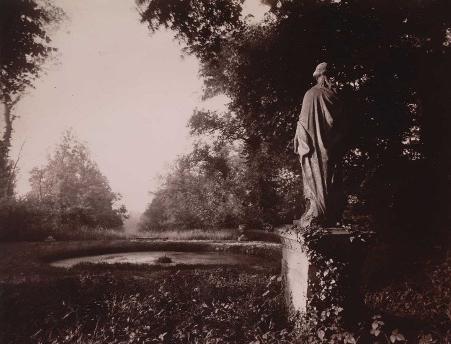

The fact that her series of photographs ‘In the Garden’is printed in platinumpalladium, ‘speaks’to this other-worldliness. Juxtaposing static ‘dead’artefacts, statues or rocks, with dynamic ‘live’plants reminds me of Edwin Smith.

© Beth Dow ‘Passage’, Levens Hall

When on my own travels with camera, I frequently look to ‘sit down to rest … in some shady place’(Amoretti, Sonnet67, Edmund Spenser). Often graveyards provide excellent places not only for eternal rest, but temporary respite.

Gardens, being not only physical but conceptual entities, are complex places. They draw out social and historical propositions and associations. Paul Strand, the celebrated photographer, is said to have undergone a ‘metaphysical turn’in his final months at his garden at Orgeval 3 . Something similar beckons as I sit in a park and look across lawns, flower-beds and ornamental sculptures in a certain way, exemplified perhaps by how statues gazeAtget-like across parks.

But what does it mean to say that gardens are complex places? David Cooper in ‘A Philosophy of Gardens’ 4 concludes that the Garden is an ‘epiphany of the relation between the sources of the world and us’.

For me there is no epiphany. I am tempted to say something like this: ‘an understanding that comes from the interplay between the conceptual spaces which gardens illuminate and the physical places which they occupy’. But I’m not sure that takes me very far, apart from signing me up as a fully paid-up member of ‘Pseud’s Corner’.

Gardens are complex places. Let’s leave it at that shall we?

Notes

1 Edwin Smith was a traditionalist eschewing new camera technology (his favourite camera was mahogany and brass half-plate Ruby) and unusual framing positions.At a time when 35mm reportage photography held sway and architectural photography was experimenting with stylised wide angle viewpoints Smith remained anchored to a more naturalistic expression of images, preferring natural light and 'normal' vantage points. This attitude was not born from a refusal to participate in photography's progression from 19th century sensibilities. Rather, if I am reading between the lines correctly, Smith was more interested in the purely visual, not some transcendental notion of the image. The idea of 'co-operating with the inevitable', as he was fond of saying, sums it up well.

2 In her elegant garden-philosophy essay. See - https://aeon.co/essays/anygarden-i-love-must-be-wild

3 Joel Meyerowitz’s selection of Strand’s photographs (2012) – ‘The Garden at Orgeval’,Aperture Foundation

4 Cooper, D.E. (2006) ‘A Philosophy of Gardens’, Clarendon Press, Oxford.