2

3

Published by Aesthetica Magazine Ltd.

This collection is compiled from the winners and finalists of the Aesthetica Creative Writing Award in 2022, organised by Aesthetica Magazine .

© The Aesthetica Creative Writing Anthology. All work is copyrighted to the author. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the Publisher.

ISBN 978-1-3999-4309-3

Aesthetica Magazine 21 New Street York YO1 8RA, UK info@aestheticamagazine.com www.aestheticamagazine.com

All work and texts published have been submitted by the author. The works featured in this collection have been selected by judges appointed by Aesthetica Magazine . The Publisher therefore cannot accept responsibility or liability for any infringement of copyright or otherwise arising out of the publication thereof.

© Aesthetica Magazine Ltd 2022.

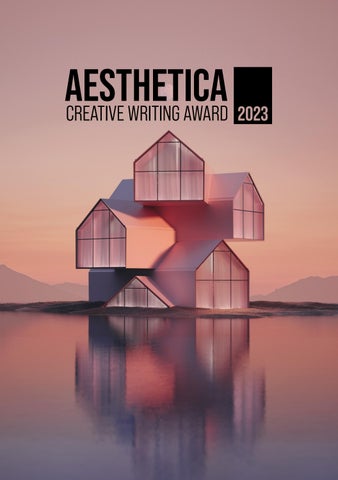

Cover image: Adriana Mora, Vitra Design Haus. Courtesy of the artist.

4

Special Thanks to the Aesthetica Creative Writing Award Jury

Ansa Khan Khattak, Haleh Agar, Liz Jones, Luke Neima, Naomi Booth, Naush Sabah, Niamh O’Grady, Nick Makoha, Oz Hardwick, Sabhbh Curran, Wayne Price.

5

CONTENTS POETRY

Bathing mother, seen from the back – a zuihitsu

The Summer Of My 25th Birthday Women’s Locker Room

Infinitives

Cist

At Once the River Cucumber and the Catbus Club

The Language of Flight My physio tells me a joint cracking looks like fireworks on an ultrasound Dreams one dreams when about to divorce Having Something a Little Stronger with You

After Frank O’Hara’s “Having a Coke with You” The night before demolition, Mary Street, 1970 Ramadan

I run with Dad

My Sister and I Went Down to the Missile Silo

The Swimmers : 24th February Four tiles from a calendar mosaic of chronic illness

A Benediction: Permitting the Absence of Tears While Mourning Thanks a lot, Shakespeare, for the Starling Good and better lies

At Ed Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations, God Tops Off His Tank The Life Elsewhere

When Things Stopped Being About Steve The only time I ever cried at the gym Unreal City

PIP

Every Time I Call, I Break The News Of My Diagnosis

Montage Theory Memory Foam Frost diary of a dead eel boy

6

12 14 16 17 18 20 22 24 25 26 28 30 32 33 34 36 38 39 40 42 44 46 47 48 50 52 54 55 56 58

10

Luna Quantum Decoherence inner courtyard Hell Mouth

Love Poem for the Twentieth Century Extradition of Drug Lord Dudus Coke: Barbican Girl Dash Weh Tivoli boy Shark Freedive in Swordfish Season Ode to Whiskey A Conglomerate Emergency with Incremental

FICTION

Raise Elbistan Sicko The Wailers Three Sailors Reassurance

In Language Strange The Etymology of a Sword Swallower Protection April The Stone A Letter to Julia Different Ways to Drown End Times Discourse Over Takeout Noodles

Beyond Words My Predictable Life A Man Digs A Grave Beyond The Low Wall The Empty House Vocation

60 62 64 65 66 68 70 72 73 76 82 87 92 97 101 106 110 116 121 125 130 135 140 146 152 157 161 166 170

7

Poetry

There are many, many definitions of what poetry is, many of which are intriguing and many of which are contentious. My personal preferences edge towards the enigmatically metaphorical – Gray’s “thoughts that breathe, and words that burn” or Sandburg’s “echo, asking a shadow to dance” – but even these, I’m sure, can cause heated debates if they’re quoted in the wrong circumstances. Consequently, I’ll just leave those hanging there and turn to the possibly less sensitive subject of what poetry needs. I’m not talking here about things metrical, lexical, intertextual, or metaphysical; rather, what I think we can probably all agree on is that poetry needs time.

Yes, poetry needs time. It’s an evident but often overlooked truth that –sometimes front and centre and sometimes ticking along at the periphery of our awareness – permeated our panel discussion as we made our final selection of the poems for this anthology and decided upon the ultimate Award winner. As any number of How to Write books will tell you – as if you didn’t already know – a would-be poet needs to make time to write and, as the better books will also tell you, to read. What they don’t tell you, though, is how much time this amounts to. In part, of course, because it’s a question that’s impossible to answer, but I suspect that it’s also because, if such things were quantifiable, it would scare off all but the most stout-hearted, thereby knocking the bottom out of the How to Write book market. Put simply, poetry requires a hell of a lot of time.

In the poems which we found most exciting, time is a crackling presence. They are poems which, probably even before their writers were conscious of beginning their composition, were wriggling about in the accumulated mulch of understanding which comes from spending time reading and thinking about poetry. And they are poems which have been nurtured over the time needed to be the best poems they can be. Nothing here takes up a lot of printed space, but amongst, around, and within these printed words it’s possible to sense – feel, even – the time they contain. They, in turn, ask the reader to suspend everything else and to enter into their negotiation of time. Whether working through an apparently simple idea by way of everyday diction and regular form, or smashing together voices, concepts, and scattered temporal and geographical spaces, these are poems which are confident enough with time to pinch and stretch it in irresistible ways that ripple in the reader’s perception at each encounter.

When, after much reading and rereading, we gathered to share our thoughts

8

and finalise details of the anthology you’re now perusing, we read our favourites aloud, balancing their movements on the tips of our tongues and – fanciful as it sounds – tasting their time. Yes, you can taste time, as easily as you can feel it (or hear it, or see it, or – sniff! – smell it). Or, at least, you can when it comes to you through a well-written poem and, make no mistake, there are very well-written poems here indeed, each one of which we commend wholeheartedly to your time.

This year’s award goes to Bathing mother, seen from the back – a zuihitsu, an ambitious work of angles and fragments which, circling from ekphrasis to domestic lyric, via ecopoetics, succeeds in being immediately and powerfully moving before it’s fully grasped, fulfilling Eliot’s dictum that “genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood.” We found it unflinching in its unsentimental humanity as the discrete elements of verse coalesced into that final, unlikely connection. It is testament to the quality of the rest of the work herein, though, that although the decision was unanimous, it was not reached without much deliberation, and amongst a number of very strong poems herein, we’d particularly like to commend Good and better lies, which holds so much in the spaces which are left for the reader. A lot of poems about “issues” (in the broadest sense) forget to be poems –a thing that this, most emphatically, remembers.

If I was going to add to the How to Write market, it would probably be a very short book indeed, and would essentially just say “give poetry time.” Maybe that’s what poetry is: ink plus time. It’s no better or worse than any number of oft-quoted definitions such as those with which I began. Having said that, in the pages that follow, you’ll find no shortage of “thoughts that breathe, and words that burn” or “echo(es), asking a shadow to dance.” And as for a parting thought with which to conclude this introduction: give these poems time and – equally important – allow them to give you time.

Oz Hardwick Chair, Poetry Prize, Aesthetica Creative Writing Award

Oz Hardwick has written seven poetry collections, most recently Learning to have Lost, and has edited several more, including (with Miles Salter) The Valley Press Anthology of Yorkshire Poetry. Hardwick is Professor of English at Leeds Trinity University.

9

Bathing mother, seen from the back – a zuihitsu

i. she’s fragile in the shower this morning we are such a long way from the old tropes of seeking understanding forgiveness

ii. Images keep intruding – Bonnard’s paintings of a woman’s legs, out straight in the bath, from the back standing, washing at a sink, in aqua and lemon bathrooms carbonated with Cote d’Azure light. It’s my mind – searching for comparisons in the file of manageable images, with which to grace the smallness of her rounded shoulders, linen fold at the base of her neck, cropped bob, legs scribbled with biro, body hair in honeysuckle tendrils.

iii . After breakfast-in-bed she says in different ways am I free to go? at one point in desperation I say I’m not the Dalai Lama , no one is that good.

iv. I walk around all day with my skin on inside out she tells the vascular consultant I’m a bully

v. The silver birch’s silky phantom-white skin is like no other bark.

vi. I wonder how I may hasten the rewilding of the European wolf. vii. Continuous shifts in the day’s perspective. Seconds thwack by on the cheap, black wall clock that looms over my son’s room – time is tiring.

viii. [things my mother gave me] (rarely) the top of the milk a handmade needlepoint of cherry blossom anxiety matching skirts on Christmas Day shares in the Airedale terrier loathing for the skin on custard a life-long cold sore indifference

10

ix. Bonnard’s Intimism magnetic suggestion of what lies behind a bowl of milk, a cup of coffee, her body magnified in bath water

x.

wolves are gentle and intelligent wolves are a threat to civilization xi. this is how I see her now I cannot unsee her I have cut her into portions the weight of her on the hoist of my body bent-wood feet her toes like polished roots gnarled above the soil xii. Betula pendula seldom live beyond 50 years. This pioneer species colonises land after disturbance or clearance, starts to rebuild native broad-leaf forest. Here is one rare veteran in Sheringham Park, after 100 years, skin roasted to a perpetual tan.

xiii. [firsts] I clip my mother’s nails, assiduously file the corners smooth – am soothed by the quiet continuous conversation of the file with her fingernails she directs me popping out the week’s pills: small round blue, peach lobes, red and white plastic pellets bright as lighthouses, pop art black-and-white, butterscotch triangles incised with a line, various as her button tin xiv. you can kill a birch tree slowly by simply driving a large copper nail into the trunk of the tree xv. At night in the outgrown rhododendron forest – in the young birch groves, by the mauve light of a foxglove colony – wolves will one day weave between the tangled limbs. xvi. Late in life Bonnard wrote letters to himself as if from friends and family. My dear child , a letter from his ‘mother’ begins. We’re just waiting for you.

Jane Wilkinson

Jane Wilkinson is a landscape architect living in Norwich. She was shortlisted for the Manchester Poetry Portfolio Prize 2022. She has won the Poetry Society’s Hamish Canham Prize, Guernsey International Poetry Prize and Strokestown International Poetry Prize.

11

The Summer Of My 25th Birthday

Everything is a lie, except ... Drinking water does help Loneliness is voluntary Empathy is not a burden

We don’t owe people explanations, and Jeff Bezos can eat dicks in space Leonard Cohen might be God New York City may lose its charisma

Maker’s is better than Bulleit “Failure” builds character, or so they say Expectations are counterintuitive Bukowski ineffably loathes F. Scott Bukowski and F. Scott were both bitter alcoholics

Weakness is not defined by seeking help Anxiety is as common as breathing I love poetry Complexity attracts

Lucifer created writer’s block Demons can be kind (sometimes) My cat is the most earnest reflection of my soul I smoke a lot of weed

Deafening vehicles imply small-dick-energy Society devours gluttony The media is pessimistic Winter Solstice is blanketed crankiness

12

Friendships can be viruses

It’s okay to outgrow yourself

Guardian Angels like to fuck with you Virginia Slims are that bitch

WOMEN are the future

Climate change is fucking real Black Lives Matter

Happiness is our own responsibility

Absolutely nothing is permanent

Absolutely nothing is permanent

Absolutely nothing is permanent

Absolutely nothing is permanent

Absolutely nothing is permanent and, I still love you.

Tor Rose

Tor Rose is a 25-year-old poet who studies the likes of Charles Bukowski, Sylvia Plath, Mary Oliver, and Leonard Cohen. In addition to her literary initiatives, she’s inspired by artists such as Jenny Holzer, desiring to leverage poetry as a means of transcendence.

13

Women’s Locker Room

after Marilyn Nelson

In the shower, it assaults me, a chemical scent so acrid it cuts through the miasma of chlorine and sweat. I roll my eyes, picturing one of the perfectly coifed women in matching pink aerobic wear, polishing her nails. High school cheerleaders grown into ladies who lunch.

A visitor to this club, I’m a stranger now in our hometown where my sister still lives. Whispers swamp my memories— my skinny adolescent shame, Lillian Wilson’s knuckles against my chest, the sound of my head smashed into the locker for fumbling a softball, the glower of girls forced to pick me on their team.

Warm water pummels my shoulders. I pause, letting it sluice down my spine before I towel off, revising my shopping list, the food I need for my sister’s kids, while she lies in the hospital with her yellowed eyes.

Stepping out, wringing my bathing suit between my fists, I stare at the bare back of the seated woman, her cropped grey hair.

14

Reflected in the mirror, marks of the swim cap rim her brow, but my gaze falls on her one tanned, leathery breast and the scar arrowing across the left side of her ribs which she makes no effort to conceal.

I’d seen my sister’s chemo port, but not this stitched up absence. Like an Amazon Elder, she shoots me a casual grin, then keeps on painting her nails, a cayenne red.

Laura Jan Shore

Laura Jan Shore teaches poetry in NSW, Australia. Her poetry collections include Water over Stone (Interactive Press, 2011) and Afterglow (Interactive Press, 2020). Her work has been published in anthologies and journals across four continents. laurajanshore.com

15

Infinitives

To admit fields are on fire, oil fields, though we do not yet see them burning; to remember our grandparents sweltered each summer, waiting for the streetcar, for nightfall; to irrigate loosened earth with native water; to bail out the seed banks, to chew our food; to call the bluff of the brand name, the marketing genius; to digest resources burnt to a crisp threshold; to savor our craving—to satiation; to be free of litter strewn beyond us steering through the Hesperides, sacred groves, Blessèd Isles, past the ghost of a man on the moon’s new frontier, our course set for the destitute sunset.

Stand 219: 16, 3 (2018)

The Ruined Walled Castle Garden (2020)

Mary Gilliland

Mary Gilliland authored the award-winning The Devil’s Fools (2022) and has been anthologised in Nuclear Impact (2017) and Wild Gods (2021). She was instrumental in developing the Knight Institute for Writing at Cornell University. marygilliland.com

16

Cist [‘sist]

noun

1. ARCHAEOLOGY. an ancient coffin made from a hollowed tree to hold the bodies of the dead.

2. from the Greek kístē. a box used in ancient Greece for sacred relics.

3. a sore that takes time to disappear.

my child is lying in a hollowed tree in the middle of a field not a tree/a wood walled grave laid out straight like a fairy sheathed in bruise/ blue hands over her chest in prayer/ not clasped /curled in a curve of rubble /death’s foetus in an open womb/ not a womb/ an ancient cist/ moon milked adorned with stalks of Easter lily perfume /not a cist but a pit/ shrouded in peachdown/ not peach/ pearl aspiring to frost worn stone/ the stone of a mother’s eye/ not an eye a thumb of light/ beaming through the pine black trunks onto the green tumulus/ a small hill/ a southern barrow/ of native earth/a flint fragrant mound swell/ of hyacinth/ descending/ as streams descend through their darkness/ to the sea /turning to the notes/ of the wind flute/ her death’s disciple /I walk in an oval/ then dance a slow jig / with her song in my head /in the last haven of sunlight /the last sunlit palm /to uphold more than a thousand roots /and a finger pointing to the bed to lie in /not her bed /a hospital rollaway/not her room/ the living room/ not the living room /the dying room of a hundred flies / talking all at once /where hieroglyphs /written in a child’s hand /on the wall/ script a legend/ of night climbing/ trying to get to the portal/ I pick her up in my arms/ and lay her in the hand hewn canoe/ stained and tarred /I have made/ for steering down the red river /where a girl runs/ through the woodlands/ and the sweet smelling rain/ the mayhaw jelly /where the red fern grows/ a pollen evensong /through the archipelagos /the sea mossed channels/ the cypress swamps /not a canoe /a monogrammed monoxylon/ good for paddling through the Greek door/ now I have to sleep on the floor /to keep her from falling /over the edge that is coming/ I can’t keep her from falling / so I make my body /her soft landing /now I’m lying in the cold cist with her /we are so close together our ear shells are touching /I’ve tied her wrist to my wrist /so she can’t be taken away/ in the night /when I’m not looking /so I can find her /so I can go with her/ if she needs me /so I can follow her in case she walks in her sleep /to comb the stone arches /below the room that isn’t her room /in the house that isn’t her house /one more time /before she finds the door /and leaves without me

Kizziah Burton

Kizziah Burton has been Highly Commended for the 2022 Oxford Poetry Prize, shortlisted for the 2022 Bridport Prize, commended in the 2021 National Poetry Competition and won second place in the Ledbury Poetry Competition 2020. She holds an MA in Fiction.

17

At Once the River

i

When her breath became a sigh we entered incandescent two bodies cut flat dark water warm embracing each pore deepness a thrill loosening our grip I touched her hand it stained my own twilight colours she said she spoke in shreds eternity filled each lisp and slur I listened host and guest till the river became our saviour and slumber: my Lord

ii

her hand was ancient as water itself ankles knees belly waist the river swelled to meet her lips what shadow is this that spills me here bitterness dripped from the tips of her hair she smiled once and then forever as if meeting a forgotten lover what shadow is this that links me so a warmth familiar as a scent remembered a breath fleeting a river sliding the whole of it beyond her reach as might an echo in mist

iii

how long did she sleep certainly not an eternity after all she’s here is she not as miracles go a river might turn into a sea of milk this one’s blood and fire howling she strips to her feet follows her steps to the river’s edge and leaps eyes raging Rosie’s no different from fire or water this she knows

iv

everything the room bed her hands and thoughts dissolved in sound a roar a storm in a bell jar’s grip and poof she’s ankle-deep in tears the river wails to no avail she’s deaf and only feels a body’s slip deeper and deeper the water fills her emptiness and leaves her tender as a new-born nymph

18

v

dusk or dawn whichever sun’s an abstraction the ferryman too there is a bank and on it she kneels this is no river her thoughts stir like bubbles rising the morass is thick of them each shoulders a murmur kiss your index to feel its presence no finger no lips breathless comes the ferryman breathless she steps in

Scott Elder

Scott Elder lives in France. His debut pamphlet, Breaking Away, was published by Poetry Salzburg in 2015. His second collection My Hotel , is forthcoming in Salmon Poetry 2023 (Ireland). This poem was first published in The Steel Jackdaw Magazine in 2021.

19

Cucumber and the Catbus Club

A cool breeze over the bento, some daikon soup, and a few bonito flakes. “Cucumberish,” notes Shiso, “the window refreshed after dancing with Cucumber’s flicks, our mind now happily green.” Leavis yawns, glowing thin:

“In fact, Cucumber’s dying, for she’s too thin.” “But the gusto,” argues Shiso, “that gargles the bento is a groove sung by Cucumber and the Catbus Club, like a green rhythm floating. Look! Let’s enjoy some Cucumber’s flakes.” “Pardon me,” Leavis interrupts, “just a few flicks of drizzles, my ears overflood like magic. See, the window now shines through me to cheer you up.” Window bewildered, her glass-eyes too thin. Mr. Shishamo, also known as Mr. Willow Leaf Fish, flicks off some extra virgin oil: “All dissonance in this bento— just starchy blunt ends—you’re merely some ridiculous veggie flakes that got me choked on your charred green nonsense; ah, now, I’m always coughing green.”

At midday, Leavis brushes the window into halos; he sees, under the sea-flakes of Mr. Willow Leaf Fish, a thinline riddle: “May the green prosper in the bento.” Leavis smiles: “Listen, light-flicks

at the end of one’s life are just purposeless flicks under the sun.” “So—” asks Shiso, “in this bruised green gruel, are we dying?” “Well,” chuckles Leavis, “the bento conjures us up as a flimsy, fleeing sense of wakefulness, and the window, so long as we speak, keeps floating along; but the now we’re in is too thin that once we stop exchanging secrets, we will vanish like flakes.”

20

Shiso scratches the flour-coated flakes, her headache loosens after a few flicks of mossy-ferny sheen. A stranger, with thin jaw bones, enquires: “Is today’s cucumber green?”

The sun halfway in, the window starving. “Catbus! Catbus!” a little girl points to her bento—

“This,” grins Shiso, her teeth sourly thin, “must be Cucumber’s darling in the bento.” “A cat-shaped omen!” rising, Leavis, “Cucumber’s gonna lose the game of green flicks.” “Oh goodness,” Mr. Willow Leaf Fish awed, “these windowflakes—”

Belle Ling

Belle Ling received her PhD in Creative Writing at the University of Queensland, Australia. Her poetry manuscript, Rabbit-Light , was highly commended in the 2018 Arts Queensland Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize. She is now teaching at the University of Hong Kong.

21

The Language of Flight

We learned to forget the language of flight, the vocabulary of take-offs and landings, of cruising altitude and turbulence.

Over seasons we became skeptics, erased our grasp the way the lapsed try to forget the lines of a prayer.

It was easy enough—entire civilizations have forgotten more— dentistry, alchemy, the location of cities, discarded like used bus tickets.

From our back porch we watched as planes slowly ascended like the faithful setting off to walk on water.

In the night sky they blinked like fireflies, and in the blips of darkness we stood transfixed, willed them not to vanish.

We came to distrust the anatomy of planes, of how fifty tonnes of aluminium can glide like a gull on a wind current, how each window holds a tiny pinprick, which somehow makes it resistant to cracking.

We came to forget other things as well—how we’d flown across the Catskills and Urals, how we walked through Jerusalem-hued streets, tasted spices that made the roofs of our minds expand beyond our skulls. In the time after flight, we learned new things to replace what we had forgotten—

the taste of fabric against lips, the sting of ethanol on grazed skin. Screens became our new educators, our new sense of faith, and through them we learned to fathom other impossibilities. How a barn can stand without a single nail. How a cow has four stomachs,

22

the lining of their second gut honeycombed. The same pattern mimicked in aviation—how on the evening news

they showed a cross-section of wing found in a field, its lining a network of metal prisms, and we thought of how beekeepers keep their hives in rectangular boxes, how bees are smoked to stop them from stinging.

Frank Russo

Frank Russo is an Australian writer and author of the poetry collection In the Museum of Creation . He is completing a doctorate in Writing at the University of Sydney. His poetry and fiction have been published in Australia, Europe and North America.

23

My physio tells me a joint cracking looks like fireworks on an ultrasound

She says I am built like a Duracell battery. She is trying to be kind about my muscles, which are coiled tight and impossible to relax. She uses other euphemisms – a brand new spring, an over-tuned string on a violin, a hive of bees. She says it makes me who I am, which she means to be a kindness, but in this context seems cruel. She puts on blue plastic gloves and says she is going to test my pelvic floor.

My whole body winces, is a slick slab on a chopping board and she is the knife. When she holds my ankles and twists them, the sad choir of my body betrays me. I am popcorn in a microwave. Her fingers taste like blue plastic gloves, I bite hard until I feel her thumbs twitch. In exchange for this, she offers me other analogies: my bones are ill-fitting shoes, stiff zips, broken screws. I am late, and a little drunk, to the party of my body, anxious in the corner, rubbing my thumb against the lip of my glass, and everyone else is dancing.

They are beautiful and freshly oiled as new bicycles; they are drinking champagne, a mesh of bright bubbles and gold. Their warmth against the cold steams up the windows so from outside, the flashing lights behind their bodies look like fireworks.

Holly Singlehurst

Holly Singlehurst was born in 1993. She was commended in the 2016 National Poetry Competition, and she won a 2022 Pushcart Prize for On Agate Beach. Her debut pamphlet, The sea turned thick as honey (The Rialto, 2021), was shortlisted for the Michael Marks Award.

24

Dreams one dreams when about to divorce

It was synchronized swimming. It was so fluid, creative, and free. I’m sure it was you, your body, every inch of your known body. Every gesture felt effortless, a spontaneous harmony. We part, we reconcile, without shortness of breath, maybe we have gills to be underwater for so long.

It didn’t strike me as strange. Thinking about it again it was probably figure skating, underwater. Here we get to the next passage, more difficult - impossiblewe hear the others’ eyes saying – They will never make itHow can they make it? - We hear their skepticism, followed by awe.

Every obstacle brings us joy and overcoming the difficulties it’s a secret pleasure, a silent, constant, internal, laughter. Again. Done. And like the sound of water, in the background, we’d hear the applause. Your ideas became mine, only one will and intuition, we always foresaw what to do. The embrace of our bodies was our shelter. Routine comforted us. How many times we had done it and done it again, every time better. Is this the golden cage of a couple?

I look at you but I don’t see your eyes. I feel your gaze, your presence I don’t know where my hands finish and yours start and it’s the same for any circle we draw into this blue that surrounds us. There is only you in every thought, in every gesture I do, only you, for me. We weren’t talking, we weren’t thinking, the babies’ cries were faraway currents. We were naked, of course, the rest of the world did not exist anymore, we didn’t care about seasons, time, where, why.

Alberto Rigettini

Alberto Rigettini is an Italian poet, playwright and screenwriter, host of SpokenWord Paris, the fight club Writers Get Violent, and pimp of The Poetry Brothel in Paris. He has been awarded The Lorca in Translation Award and the Troubadour International Poetry Prize.

25

Having Something a Little Stronger with You

After Frank O’Hara’s “Having a Coke with You”

Having a drink with you is harder now that you’re dead. Though I still remember my first drink was with you when I was 19, the product of a teetotal home. No booze, tobacco or playing cards. Years later, my father dead, my mother living alone in the house, my brother brought a bottle of wine to dinner and my mother, tight-lipped, served it in liqueur glasses. No seconds. Teetotal meant that as a child I wasn’t supposed to know about the mysterious bottle at the back of the bathroom cupboard marked “For medicinal purposes” and fortunately, as far as I know, it remained unopened since we were a family never in need of reparation, rejuvenation, stimulation or comfort. So when you and I, teenagers, first date, no car, just walking down our town’s main street, down past the local watering hole, you said, “Want a drink?” and I said, “No thanks, I’m not thirsty,” you laughed and said, “You don’t drink because you’re thirsty,” which was a revelation. So I had something with ginger ale which I’ve always hated, and what was mixed with it, don’t remember, maybe gin or rye. It wasn’t all that bad because whatever it was killed the ginger ale and started me on my education exploring things that mercifully kill ginger ale, i.e. vermouth, more gin or rye, or even plain old tonic. Anyway, as I said, having a drink with you after marriage, divorce and what would have been widowhood if we’d stuck it out would have been our bond, though the old pub is gone. I’m told there’s one in the new north mall where I’ve never been, having left town years ago.

26

So here I am, here you aren’t, I’m raising a glass while I still can, something alcoholic that blends with something else alcoholic or maybe lemon or grenadine or Clamato or ever-handy soda water. Lots of ice. And the memory of Frank O’Hara saying I love you on the strength of a Coke and I believe him for why else would he say it in a poem? Whereas I can drink myself blind and the words won’t come which is more like a letter or a poem that never rhymed. And I sometimes think of that evening long ago, how much I learned and how it shaped my life though not the shape my parents would have chosen, and how I never told you but have to say all this now, not with love, regret or whimsy, but perhaps with guilt, who knows. So listen up! I’m not believing — can’t believe — it’s too late. Ever.

Miller Adams

Miller Adams is the author of a two books of poetry. As Sylvia Adams, she has written a novel, two poetry books and two children’s books. She is the twice winner of the Aesthetica Creative Writing Award, amongst others, and has work in over 30 publications.

27

The night before demolition, Mary Street, 1970

We never knew the exact time when all this would be knocked down, generations have passed on to each other this simple ritual; breath to breath to breath, bricks huddle us in these tenement temples.

Anything that could have been sold is gone, there is just us now, making patterns on the scuffed carpets before the wrecking ball swings in the pendulum of progress.

Wine bottles line the sills, in them we see small versions of ourselves, angels that perhaps we weren’t meant to see but do. It is but a pause in our incantations, we keep pressing on, learn the steps by fumbling, gaining purchase for the next time.

In the corner remain the imprints of an old armchair, marks where the legs wore through the felt underlay. From that chair my grandmother told stories of banshees and vengeful ghosts, we were rapt as we learned how death and life are kept in terrible balance, a balance almost forgotten now in our daily violence.

The bottom half of a statue of Our Lady lingers on what is left of the hearth, her other half having ascended up past the mantelpiece and through the exposed beams of the ceiling. In the air Novenas repeat and swirl in the spit and plash of a starting rain, words and tears are felt and listened to more for being incomplete.

28

Perhaps we will see the dawn filter home through the rafters, through broken windows and doorways with scar-hinges, the future will be made in us, in moulds that break, so we must keep our hands casting fresh shapes.

Glen Wilson

Glen Wilson is an award-winning Poet from Portadown. He won the Seamus Heaney Award for New Writing (2017) and the Jonathan Swift Creative Writing Award (2018), amongst others. His poetry collection An Experience on the Tongue is available with Doire Press.

29

Ramadan

The hours play out each shadow: bluebells, wild garlic, the flowering quince spread

each inch of the morning, I measure their three sixty turns elongating, shortening, drowning the first hint of bumblebees. The clock wasps, amoral lashes keep tab on

the lengthening minutes of the sun, I serenade each fly landing on thighs wanting to be exposed, I want to subjugate restless souls by lying still, splash savage wings in lachrimae murmuring non-violence incanting the whole lunar month - this

whole April, my merciful axe is a blade sheathed in bacchanal, daddy-long-legs still forming, fit snug inside my half-glass lent out to the wind. At the vertex of sun

I dream up a tramontane, a gust to figwort my glands, quench each parch. The day

done, at sunset I am mad, certified, I’ve re-lived all the berries crushed, and in

30

Kincraig St the calla lily in the garden front looking up to the last of the crimson, its spadix thrusting a yellow pine for the sky drifting from the milky spathe wanting to

hold on, I walk past unacknowledged - I’m on a mission to calm the guttural Bay of

Bengal. The first droplet is a lightning rod flute to temper each sand-grain fit for a

palm to dip, imprint a dusky maghrib azan - the day then begins all over again.

Taz Rahman

Taz Rahman judged the 2021 Poetry Wales Pamphlet Competition and has been published in Bad Lilies , Anthropocene , South Bank Poetry, Honest Ulsterman and Poetry Wales. He has been in the 2021 Literature Wales ‘Representing Wales’ writer development programme.

31

I run with Dad

I run with Dad. Short reps on cut-gorse flats, six by one mile efforts, two minutes between, seven ten to fifteen pace, out and back. He is Fieldfare, diagonal in flight, sinewed and eddying on hedgehog paths, and is sky washed fresh, a contrail at birth, sniffing Cymraeg; pores foam, strides winterish mulch, fires thirty words for pelting rain, nostrils froth, rotmud barkmould ashbog, stile slime, birthmarked by moss, salted sweat, his pate a delta of rivulets, we are twines of the same lickety-split lichen, fern eyed, mule stubborn, charcoal laugh, puddle drowned and wind arched, cobble tracked, a mottled moon-mist shrinks sightlines to treespines, each spindling limb groans its canticle, stripped galleon masts in gales. He kicks - sodden earth stains his shrinking freckled skin, flecking Sedge-Rush-Melick-Brome, his front teeth whistle, jackrabbiting creeks, he is my age, the youngling, running, peat blackened, stone clack, hoar-frosted by mire, chaffinches skimming in his turbulence, uprooting turf, purposeful swing of whirling dervish. His heart is a lesser-spotted comet, a downhill fireball, he is a blooming thornbush, a heavenward promise. Dad is holding his new-born children, he is slow dancing with his wife. He is way out front and flying on his fabled sandy spit. He is half meadow-grass and fungus. Ligaments grip, ache, drovers road cattle grid, our furnace lungs of magma list, hail of sharp pitched factory alarms and tin whistle shrills, chewing limes and shrapnel, we hock a lactic surge, chattering grins, the script of his age beds back in. He pulls up slow - we jog home. Wash in the same bathwater, greasy in nettle stings and woundwort, algae latching to the taps. He says he feels a new man. His thumbs grip a hand so hard the knuckles crack. He is bright, ripples from a pebble punched pond. He sweeps toast crumbs from his lips, cleans the grate, builds a fire, and sleeps in the watch of it. He is proud of all things. Good run.

Geraint Ellis

Geraint Ellis is a Welsh Northumbrian poet. He is a Barbican Young Poet and former Scottish National Slam Poetry Finalist. He was shortlisted for the 2022 Bridport Prize and Aurora Prize. His work is published by flipped eye , Broken Sleep Books , Abridged and more.

32

My Sister and I Went Down to the Missile Silo

when I was thirteen. In our tallest boots we waded through a long-flooded tunnel breathing fug and rust. I clutched my flashlight but wasn’t afraid: I was high with it— wanted to lead the way, take us farther, deeper—wanted to touch the darkest dark with my little beam of light, with my hands. We reached the silo. I toed the cut edge of the world, leaned out over a black hole— water, far below. A giant mirror. If I broke it, I’d sink seven stories. From somewhere in shadow, my sister’s voice pulled me back. Who are you trying to be? The darkness took the words I couldn’t speak.

Alice White

Originally from Kansas City, Alice now lives in rural France. A graduate of the University of St Andrews, she is a recipient of the Langston Hughes Award, a Hawthornden Fellowship and numerous scholarships. This poem was first published in The Cortland Review.

33

The Swimmers : 24th February

2. August. Deutschland hat Rußland den Krieg erklärt. – Nachmittag Schwimmschule.

Franz Kafka, Tagebuch 1914

The swimmers crawl their way along the lanes in the afternoon or breast it in some clumsy style. Swimming school kids flock at the start of the lanes making the options narrower; in their cheery mayhem a few eyes scream in the throes of the unforeseen. Is it they already fear death? By drowning? Or is it the cold? Puffy dreams off a swimmer’s scalp hover some instants like bugs above the tarmac as others scream their lungs out not making waves or shed tears underwater. And others fancy closing their eyes & keeping their crawl straight, but they don’t. They are not aware: they swim inwards drawn by triggering aches in those haunted corners of their bodies, drawn by cunning schemes about the rest of their lives, starting the moment they lift their flabby bodies over the rim of the pool —but it’s all an illusion, like strokes get easier after minute 20, like they aren’t annoyed by the old and the unfit. Nothing seems ever to change bar everything changes impassionately and ineluctably, and then the swimming ends in mid-afternoon.

34

They raise and run, clumsily pack whatever & don’t forget the cat in her cute spacecraft carrier & shouldn’t they have foreseen all of it—but they always do that, they look the other way as if the ripples in the water don’t always forerun a tidal wave, or it can be easily breasted over.

Eyes-closed some find their way out of home on their finger tips along the walls. Some drag their uniforms across the lanes as Russian paras drop like flabby tears down their rifle sights. How casual is to get yourself killed at age 20 and your photo circulated in socials as a frosted chunk of meat by the tanks bar bodies peppered with shrapnel on the tarmac, a suitcase the only mourner. Run, drag your life-heavy wheeled suitcases and your cute cat-carriers, flock at the platforms for those metal eels or race-drive your lives past them all others, or take the contrary lane, or leave the old and the fragile behind —the shells explode like odd achings of the body, triggers, or the military craft savagely crawl low past your clusters like locust, big time locust. But nothing ever changes.

Joan García Viltró

Joan García Viltró is a teacher and poet based in Cambrils, on the south Catalan coast. His poems reflect Mediterranean mythologies and his concern with nature struggling under human pressure. He is published in The London Magazine , Full House Literary and more.

35

Four tiles from a calendar mosaic of chronic illness

The darkness is as heavy as the sea in this room Light creeps out from the top of the curtain rail

In yellow-shark grey and folds across the ceiling

With the refractive torques of a sea-sky cutting

Over the surface of the deep. The folds of sheets, Long unwashed, long lain in, touch skin at certain Points with such doubled sensuousness, like lips

Against the rising force of soda. The pain is a Months-long voyage and the crew are bored And mad. My dad says you just take it like a rat.

The doctor is leaning forward clutching a coffee

In a polystyrene cup as if its white ring’s a life Float. He has lost hair since our last appointment. This is a very long clinic, he says, hopelessly. Didn’t you have an operation at some point? I don’t tell him at home I call him Wizard of Oz

Or of the long yellow brick road of referrals And refusals and referrals. I don’t remind him

About the day he said ‘I can fix this: I’m good. And I’m usually right’. He refers me to a shrink.

36

Dad’s just back from visiting Great Uncle Tommy Who’s 94 and proud and still hasn’t braved the bath Since Dad’s last visit. He was in the Navy during the war. Said he didn’t want to get his feet wet. Now his suit’s

Too big for his little frame and has god knows what on it But he says he’s alright. When Dad went into Tommy’s Bathroom to fix the grabrail he bought him, the tiles Came away as he touched them. Tommy cracked jokes And told lies. Dad’s face is like the back of the tiles

When he gets home. I don’t like to tell him, he says.

That must be nice for you, the receptionist smiles, To get to stay home all the time like a holiday. She hands me the invoice for my treatment, folded.

On the tube, white people pretend not to look at everybody who looks Asian. They stare more openly, though, at the First few face masks, sidelong. Then the announcement: You must stay home at all times. Even before A week is out, everyone understands me: even free

Of the smaller cage of sickness, the walls of home are Too tight. To breathe, to be, to feel: that must be nice.

Jo Davis

Davis’ poetry is in PN Review, Magma , was Highly Commended in the 2021 Bridport Prize and Commended in the 2022 Troubadour Prize. Her debut pamphlet, Dry tomb (Against The Grain), is out in 2023. This poem was first published in the 2021 Winchester Prize.

37

A Benediction: Permitting the Absence of Tears While Mourning

after Hyejung Kook / after Adrienne Rich / after John Donne

Bereft, be left on the outcrop though others cry. Departure takes its own directions. Let it

walk along fissures of granite to howl, if it wants, into earth’s crusty ears,

for this, too, the earth will accept. Give grief its wandering into museums to resent or envy any curated past

or to loiter in foyers and stare at lightning. Precipitation need not be measured. When the clouds lighten,

listen to the cooing the mourning dove calls neither song nor mourning.

Bradley Samore

Bradley Samore has taught English and writing in Spain and the USA alongside work as a school service worker. The Palm Beach Poetry Festival named him a Thomas Lux Scholar in 2022, and his poetry has been shortlisted by Aesthetica and River Heron Review.

38

Thanks a lot, Shakespeare, for the Starling

The window, single-paned to preserve not heat but historical significance, presses down upon the simple plank preventing it from shutting; & in that humble rectangular board exists a hole through which reasoning escapes, a metallic accordion-like tube stretching from the dryer’s back end to the aperture where the starling enters, where it places twig after twig to construct a metaphor for impracticality

& absurdity, a snapshot of modern life & our climatic uncertainty, like building a home on the rim of a smoldering caldera, its flimsy walls trembling. In 1890, 60 starlings were released in Central Park by the American Acclimatization Society because Shakespeare made mention of them in Henry IV, Part I, wrote “Nay, I’ll have a starling shall be taught to speak nothing but Mortimer, and give it to him to keep his anger still in motion.”

By the end of the play, the battle rages on, the Hundred Years’ War still unresolved; Now we’ve got over 200 million starlings in North America: My wife & I let this one stay. We hang wet clothes upon the backs of chairs, upon our shower rod. We learn to harness solar energy, to do without these modern conveniences, & teach our 2 sons to appreciate the subtle rumblings of an egg set to crack, of a fledgling poised to press its luck upon the ledge.

Jonathan Greenhause

Jonathan Greenhause’s first poetry collection, Cupping Our Palms (Meadowlark Books, 2022), won the 2022 Birdy Poetry Prize. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in The Fish Anthology, The Ginkgo Prize for Ecopoetry and The Rialto, amongst others.

39

Good and better lies

like this, wearing a veil I will evade evil on my way up the escalator while on the phone to my sisters. When exile began, I turned my head to laugh. I chose one stem of thyme, a handful of barberry, a spoon of burnt sugar. The market floor is the basics of theatre. From Isfahan

to beyond river Karkheh, meaning Four Edens, meaning you can find a canoe between borders of paradise. When all allocated segments

of holy and half-holy water were behind me I ignored my city; ignored my rain; ignored my nosebleed. Don’t worry, the way to begin in another place is about arriving.

Soraya, Damsa, Shirin, here I have told them we drink, I have told them we dance, I have tried violet creams, lemon meringue pie from England.

I was promised I could cut clean hair in salons and play the quiet war in a house from a radio like a song our mother is crying in.

I have forgotten homesickness is a bridal hormone, that some of use claim there is a city near the sun liberated by a commander woman and if you die by the hand of a daughter you will not go to paradise.

Tonight I am craving liver and earth, you sisters. I have more in common with the properties of birdsong than this language:

40

A proud cuckoo will mimic the orientation of the satellites, the public silence between sun keepers, the plural voice of the commander when she said annunciate you have permission to sing.

Eve Esfandiari-Denney

Eve Esfandiari-Denney is the current UEA Birch Family Scholar and author of My Bodies This Morning This Evening, Bad Betty Press, 2022. Her poems have featured in The Poetry Review, Polyester, Bath Magg and The Manchester Review, amongst others.

41

At Ed Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations, God Tops Off His Tank

God is the God of oil pastels, of Montblanc fountain pens, of Farber mechanical pencils. God idles his convertible at Ed Ruscha’s twentysix gasoline stations. These are the service stations of the cross, each a grayscaled sermon. Above, the alphabet’s holy letters luminesce by night and day.

In the Mojave of Joshua trees, it’s all heat stroke and sepia. It’s not enough for the God of armatures and Sennelier paint tubes. He wants a fuller range of California light.

Now God lifts the trunk of his Pontiac which is the Ark of the Covenant. Now God lifts Twentysix gasoline stations from its creche. Now God raises Esso and Sinclair from the dead. Always every instant is with Him.

God particularly likes the flattest shot, a sidelong Union station in Needles. God doesn’t need perspective. Why should He care about vanishing points? Objects loom large not because they are near but because they are holy.

God knows the twenty six filling stations and the seventy-eight pumps. Each is large on the lakebed’s flat gravel. He doesn’t take road trips to get anywhere. He just loves to drive. He loves to move inside his own work. He is the God of Canson drawing books, the God of Pelikan inks, the God who nails canvas sail to lumbered stretcher bar.

As for Dad: he heard Nat King Cole and hitched from Chicago through San Bernadino. All the way West, his rides pulled off road to fill their tanks. While Ruscha was still a boy in Oklahoma City, Dad walked those gasoline stations, taking them in with his own hazel eyes.

42

As for God: He doesn’t care much about time. For Him, it’s all the same moment. From his powder blue Pontiac, God sees Ruscha and God sees Ruscha’s book. God sees Dad, gangly and serious. God looks through Ruscha’s eyes and through Dad’s eyes. God peers through the eyes of millions driving themselves from one place to the same place, from one century to the same century.

God loves the city of Needles. Nowhere else is God so happy. Dad’s always in Needles, Ruscha’s always in Needles. The whole nation’s left the highway for the Union 76.

As for Dad: he’s caught in the gone moment, just like Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations.

We all head toward the vanishing point. Then we vanish.

Tom Laichas

Tom Laichas’s recent work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Rupture , Disquieting Muses , Stand , Ambit and elsewhere. He is recipient of the Nancy Hargrove Poetry Prize and the author of Three Hundred Streets of Venice California (FutureCycle Press, 2023).

43

The Life Elsewhere

To pull wild mountain thyme all around the purple heather, will you go, laddie, go.

Wild Mountain Thyme

Grey hair and morning face in the bathroom mirror, panstick white with shaving gel that needs no brush to lather smooth, and every wrinkle and crease is obscured by this massaged, soapy fleece, except about the eyes, that skin above the lush, luxurious, layered snowfield made clearer

by contrast, its corner lines and relaxed tone of softened circles, slightly bluish in hue below my eyes, the eyes carefully watching, monitoring the razor’s work, matching pressure and angle against face value, careful as a conjurer shaving a balloon;

and remembering teaching my son, saying, Take your time, take care, don’t rush, it’s not a race. Though they sail past these markers anyway: voice breaking, first shave, first love. The firsts that can’t stay, falling behind in the days that change your face in day-by-day years there’s no delaying,

those accumulations we notice slowly then all at once, knowing we see children grow older while deep down somehow believing we don’t, at a standstill in each moment leaving in this world of movement and winds that blow on the lives where we locate all that’s holy.

44

And I thought of rooftops and the sky above them, and how sometimes you see floating a stray balloon, escaped, high in the grey or blue, or let loose and making its way, moving through your confined perception, up, up and away, like children grown up, both in and beyond your love.

The beautiful balloons breasting the weather out there in airy currents we cannot see, voyaging, the way we leave one nest to find another place to come to rest, loving our children to let them go free, knowing this is how we all go together.

Roy Kelly

Roy Kelly has written extensively about Bob Dylan for specialist magazines, leading to the publication of a memoir, Bob Dylan Dream (2015). His poetry book, Drugstore Fiction , was published by Peterloo Poets in 1987, and he has many poems published in The Spectator.

45

When Things Stopped Being About Steve

Steve likes his boxing gloves to hang from the rearview, miniature oxen balls in the breeze. A blue rabbit spools cotton from the grill. Steve keeps the radio on for luck, nothing safe about a heavy-duty truck on the motorway. A kicking foal connected by a breakaway cable. The BBC keeps him company on the long road to France, gridlocked at the Channel amongst mackerel sandwiches and seasalted cigarettes. Steve kicks the butts under mud, later picked up by a crustacean in need of bedding. Steve has made this trip on nearly eighty separate occasions, but this isn’t about Steve. At best it’s about a memory of his. Something he heard on the radio. Something he tries to forget to get back his sense of the world, yet when he tries harder he remembers the taste of the memory, of ashen, tomato-pasted fish on Kingsmill fifty-fifty. Of thirty-nine people found in a lorry not dissimilar from his own. Of thirty-one men and eight women who were trying to find a home.

Nichole Alexandra Barros Moss

Nichole Moss lives in Bristol, UK. Her writing centres on issues of class, identity, family and migration, often with a surreal or magical-realist twist. She works as a film production assistant and tweets about films at @artduckies. This is her first publication.

46

The only time I ever cried at the gym, apart from when I broke a balance beam with my head, was in yoga class. The teacher,

in her bow pose, switched on “Love to love you, baby.” Right into the second chakra it went, just above my pubic bone, when something very much like my head, but lower, burst.

Only a month before, I had lost a baby I wanted and a man I didn’t, one after the other.

In my bow pose, holding my ankles, pelvis rocking on the mat, I started to cry.

I had no idea my body had baby memory. A current ran through me, very like when my head unexpectedly hit the beam and I found I was still alive, or when years later, I held my mother as my grandmother died, feeling through her body, my grandmother’s life in me. In the yoga class, what I felt was distinctly the other way around, a life that almost was but now would never be. A part of me had died, and a smaller part of my mother and an even smaller part of my mother’s mother and so on.

Paula C. Brancato

Paula Brancato is the 2015 winter of Tampa Review’s Danahy Fiction Prize and Booth’s 2015 Poetry Prize and Second Prize winner in Cutthroat’s 2019 DeMarinis Short Story Contest. Her work has appeared in Ambit , Kenyon Review, GSU Review, and elsewhere.

47

Unreal City

We were living in that unreal city.

I watched the Peregrine Falcon raise its ragged chick through @birdlovers’s canted camera.

I sent @emily37 a tin of Anzac biscuits because she posts she was low and because she sent me pretty masks embroidered with thorns and bees which she says suits my personality, although we’ve never met. I tell her there’s a key hidden in the biscuits, she can break out of this lockdown. Every time someone logs off it’s as though they’re dead, or joined a cult, gone off the glowing, flashing grid.

I looked over the shoulder of a dozen solemn speakers and read the spines of blurry books. When we all did the Ode to Joy, I was the sixteenth da DAH. There are 2.7 million views of that.

I could almost hear the distant rumble of the armies of Uber Eats knocking on our waiting doors. There was a lot to do in that unreal city and mostly we did it. I preferred to – this was an important distinction, almost my signature.

If I moved my mouse every 10 minutes, the computer didn’t sleep and I would show as active.

I didn’t need to shave my legs, which was good, my parents understood Skype, blew kisses.

One day I watched the pelican that was circling in the broody sky outside my cold apartment, make its ponderous way to the ground, like a cargo ship piloted slowly into port and for the longest time I couldn’t comprehend how it could be outside in that chilly rain or after an eternity of falling, where it would land.

48

Damen O’Brien

Damen is a multi-award-winning Australian poet, including the Magma Judge’s Prize and the Gwen Harwood Poetry Prize. Damen’s poems have been published in journals around the world, and Damen’s first book of poetry, Animals with Human Voices , is now available.

49

PIP

We met in the time of pips, pennies pressed into boxes in corners of union bars, laughing, shouting over the din.

I mailed you drawings, photographs taken in a terminal booth, a leaf

the colour of October. You sent back mixed tapes, sheet music, some song you’d composed with my name. In spring I folded violets into April-blue paper, afterthoughts scribbled in the margins, in green pen, for luck.

Then there were calls patched between continents an operator, Gene perhaps, or Jeanne, in some remote hill station, carefully connecting thin copper wires, me, all the way to you.

We spoke in the gaps between echoes. Clouded by oceans and desert, our voices were intermittent, then abruptly disconnected. Your mail arrives without warning or parade, my screen lit with your name. Your children (three) have flown the nest, your wife, too.

You’re not sure why you’re writing, you like to think I’m okay.

50

Silence hums in my ears. It’s midnight, an hour I always think is neither one day nor the next.

Sarah Easter Collins

Sarah Easter Collins lives on Exmoor with her beloved ancient lurcher Siddley, where she writes and paints to keep him in dog biscuits. Her debut novel will be published by Viking (Penguin Random House) in early 2024.

51

Every Time I Call, I Break The News Of My Diagnosis for my

father

The clouds tower over you in Florida, the gray-roofed house you refuse to sell, the lawn you insist on mowing yourself, and gone, now, to clover. You remember enough to ask about the cancer.

You ask How much longer? What is it like to hear it—the sadness in some untouchable way familiar?

Perhaps this time I can be gentler. What I felt in my lungs was a nightly fire, was a sunset keeping me from sleep.

You say the vines are taking over— sacrum, spine, clavicle, tangled—the woods next door keeping out the light. Does it do any good to tell it? The science says I won’t outlive you. Who will tell you then? And how?

I am weak-limbed as the orange tree you took out last December. Or was it the year before? You can’t recall.

The gray lines of the live oak break through you, the untimely drop. Your heart flutters down. I hear it.

I walk around with a flower in my chest— azalea—a pink that comes too soon to last.

My ribs are a dusty glass the birds flap into. Sometimes, an alligator appears from the dark lake of night and braces down on my right femur. I say all this. Gentle. But every time you find it—a field that blooms inside you, optimistic, bright— and perhaps this is why I call. What if everything turns out okay? you say. And it doesn’t even feel like a question.

52

Laura Paul Watson

Laura Paul Watson lives and writes in Pine, Colorado. She is a graduate of the MFA program at the University of Florida. She was shortlisted for the 2021 Manchester Poetry Prize, and her work appears in Agni , Poetry Ireland Review, Beloit Poetry Journal and elsewhere.

53

Montage Theory

The pile of bricks my father carried down the steps to the garden had been acquired a week previously at the Mumbles hardware store. Now, he was laying them in courses as I watched from the shade of the cherry tree.

I intoned back the names for him as he had taught me: soldier, shiner, rowlock and at the end a closer. He sat back and asked if they were straight.

I wasn’t sure so I whistled like I’d seen in the movies. He laughed and placed me gently down on the wall. Or maybe he took my hand and led me back inside.

I often find a wish going through me to remake myself as a filmmaker. Those bricks, that scene, would form the heart of my first film. I wouldn’t bother to signal motivations. I’d stay faithful to that old Russian concept, the collision of shots. Things would just happen:

flakes of stone on the passenger seat, the spirit level close-up, a jump cut between my hands, his.

Then just before it peaked, I’d cut years ahead to a character we’ve never met, looking out the window, lens-flare drowning her in light, the camera dead still until the very moment she looks directly at it.

Jamie Cameron

Jamie Cameron is a poet from the Midlands, currently completing a Master’s in Creative Writing at the University of Oxford. He has poems published in Anthropocene , Swamp and The Vanity Papers. Away from writing, he spends time playing and coaching basketball.

54

Memory Foam

We lie side by side

as we have done for years, sometimes touching, sometimes not, separated by the posture sprung dreams we dump in a ridge between us. Today men come to replace the mattress with a pristine slab of memory foam that has amnesia decorated in damask roses, baby blue and pink with vanilla piping. Like much of England we will slumber in cake. I supervise removal to a van already crammed with other sleepers’ king size geologies, stacked on their sides, the soft cliffs of our lives layered with flakes of old skin that shone in birthday candles, peeled on pebble beaches, ached as it froze around snowballs, scarred the heart’s geometry on tender wrists, puckered up to a lover’s touch. All of us making our way ahead of time to landfill where to be a crow is to glide in paradise.

Mark Fiddes

Mark Fiddes’s last collection Other Saints Are Available followed The Chelsea Flower Show Massacre and The Rainbow Factory. His work has appeared in Poetry Review, Magma , London Magazine , The North, The Moth, Poetry News and The New European .

55

Frosti

some kind of smokiness still in the air and December fell as falling frost fell from out of the mouths of cooling-towers

their plume a luscious whiteness against the ice-blue sky whiting the down-wind downs and fall-out fields to look a bit like Christmas children drove sleds down reluctant slopes built a snowman at the bottom dressed him in coal lumps dead twigs a cough ii the frost that fell from the towers’ plume fell gently almost warmly as ghosts might be ghosts of long-ago un-named things released at last from geologic purgatoryafter so many snowballsto make a joyous snow

children their blood so warm and heavenly built a snowman made him smile

56

iii the children’s breath in plumes fell ghost-like up to a winter-soon night of sky their feet where they crossed the homely rug let fall the little frosts and in the dimming fields left a snowman inhaling all the light

Gareth Alun Roberts

Gareth Roberts has had poetry published in: Orbis , Envoi , Acumen , South, Welsh Poetry Competition Anthology and National Poetry Anthology. He published What’s Not Wasted (Tawny Owl Press, 2016) and was awarded second place in Poetry Space Competition 2020.

57

diary of a dead eel boy

at the wane of day my father and I would strike out small in tall rush and long shadow greasy wellies and waders orange and blue through kloo-ik kloo-ik and a-wick and a-wick

split the green curtain he did with his club-fingered hand and bid me break my slipping gait with the sober refrain care is the order while hopping goat-like scree and rock chimney

at river’s edge we left good altitude leaned one the other on sharp degrees waterward and entered the lair of the eel down to the killing stone mucked with bone gut and gill spillers he’d take and drive the stakes like a looney railman laying bed and ties into the sea gather line and hook under foot and stab a worm fatway short to make show of the ends

out went the line and sinker straight points aft of entry and father and I bent crooked obtuse and tautness in the hands that were the sign of a true lay or untold fears coal lorry black and then he bade me do that thing that was holy of holies and life for life and seed for seed but come the shot recoil and treadless boots come the slip fall and lumbar shock at sedge bar and bubbling ho! and breathless hee! and gasp and pee and neck and ice and skin and smart and entropy and amber trilobite and salt shad and mud fart and snot jelly and black hole

58

and father cursing the weight of the boy and sinkers of melted led and iron pipe and always the hook and the mouth and the boy’s leg for anchor and bloody minutes cut into his hands

until the earth gave way at the bottom of the world to the mud golem and the O-mouthed oily thing wrapped long at his leg and father looking fire-eyed and hell-bent at eel and eel boy

and stomping spineless and clubbing paste-wise the jaw eyes and tooth plates in its ugly face and returning next day with the sober refrain care is the order and spillers worms and hooks

Dean Gessie

Dean Gessie is a Canadian author and poet who has won dozens of international awards and prizes. These include the Aesthetica Creative Writing Award in Poetry, the Allingham Arts Festival Poetry Competition, the Samuel Washington Allen Prize, amongst many others.

59

Luna

This afternoon, my Mjölnir-wielding son chased Luna around the back garden till she crashed face first into the sycamore. As he kneeled in the grass to check on his new friend, his face a crumpled moon, the Malamute growled and her fangs grazed his cheek. It took four tales from Arabian Nights

to get my boy to sleep and it’s now past midnight. He kept looking out the window, picking his crimson scab and asking for his mother. No doubt she’ll stab me with a stare and tell her lawyer that I ruined his face forever. Luna is resting in the kennel. The crescent moon that lights up her muzzle is a battle scar. Lemongrass

won’t soothe me and I can’t stop glancing at the grass. What if, instead of this cricket-ablaze summer night… Our madeleines are just right. Yet the moon espouses the colour of poached damsons and wears my son’s face. I seize the Messermeister Oliva Elite.

I can’t believe you spent that much on a knife ! But you couldn’t get enough of my grass-fed angus with celeriac purée and morels. I hope his orgasm face is uglier than mine. I miss you. I hate you. I cry every night and you’re a leech who’ll fail to slurp my son from me. May the almighty Thor ruin your honeymoon.

Fuck your honeymoon. The olive wood handle numbs my fingers and the blade takes over. A father would do anything for his son. Build a blanket fort. Praise mum. Drown the grass in blood and bury a dog in the candour of the night. I will hold her close and feel her last breath on my face.

60

My boy will never have to be ashamed of his face and my soul should heal before the new moon. The sycamore weeps its leaves and implores the night to scrape off my grimace and hide the dagger in honey. Crimson grass. Madeleine. Crimson grass. Is that an owl or the cries of my son ?

My son lies in the grass and warps the night, while a faceless knife, reaching for the stars, decapitates the moon.

Amaury Wonderling

Amaury Wonderling is a London-based poet and filmmaker. He has been published in Blithe Spirit , STREET CAKE , The Cannon’s Mouth and Abridged . Luna was commended in the York Poetry Prize 2021 and first published on their website.

61

Quantum Decoherence

Tom Petty is unreliable as a narrator. Do we really believe he doesn’t miss her?

Through the butterscotch scented Jeffrey Pines, I glide up Coldwater Canyon to Mulholland thanks to the uninterrupted ease of my continuously variable transmission, its conical ingenuity—a wonder, second only to the Bluetooth conducting quanta in airwaves or ether—mechanized music of the spheres.

A physicist will tell you the moon itself is in free fall: a predictable trajectory that reads like a mixed metaphor.

I thought the Valley was a thirsty place, burnt from a lack of ozone and condescension from shadier zip codes with bay figs and kumquats, but here I really drive west down Ventura Boulevard, the trumpet trees in their Barbie pink reminding me of cherry blossoms, of northeast springs, that the address on my licenses has never matched

the address on my lease, that quantum mechanics can unambitiously tell you where a body will be— or at least the probability where it will be and maybe even then, a little off to the side.

62

Heisenberg thought nothing exists in space until you look at it. Was I only visiting this mythology until I rode my brake down the backside of the Canyon, seeing the vapor that had risen off the Pacific and got trapped in the puckered folds of the mountains? What a pity they call this smog.

Further south, bells are ringing for the return of the swallows. It’s a reminder that migration also means to come back home.

Brookes Moody

Brookes Moody earned a PhD in English with Creative Writing from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, where she taught literary journal production and creative writing. Her work is published in The Mississippi Review, The Literary Review and elsewhere.

63

inner courtyard

i. campanula poscharskyana

bellflowers trail roots in walls pushing gaps between paving my inhospitable patio open to sky your five-petalled resilience constancy of lavender -blue from a cursed mountain distant alps romance & hope never die unwanted nourishment gratitude unfavourite virtue uproot you –you again full-flower weeded out another way in with silent chimes like family that will never be rid

ii.

nymphaea

pink pond-flower sensation of resurrection joy & enlightenment morning prayer after a night of deep mud how your green leaves protect & shade hold us safe & stretch to any space for too long keep out sun birds like anyone you float for peace & meditate on beauty shortlived as scent our three-days together till the next onoff dart between fish stillness & transience captured in paint

iii. jasminum officinale

the gift you gave me cannot stop euphoria & sensuality from the gods turns a girl into an ajana goddess with jasmine cleopatra soaked her mainsail for mark anthony is love protection meandering is a bind for community the shot arrows of motherhood & my grandmother sprinkled stars on my dreams butterflies don’t only drink tears hummingbirds fly backwards & deer polygamous old relationships undie

iv. pelargonium x hortorum

fill pots on the patio they may be geranium cranes are confused with storks their long narrow beaks carry seeds & leaves vie with mint ginger eucalyptus lemon for salads puddings & tea i bathe in a poor man’s rose of attar reflecting on happiness folly & why you & i split the way nations get divorced & i have never visited south africa but you want to take me there to see again where it all started

Mary Mulholland

Mary Mulholland’s poems have been published in a range of magazines, and she has won, placed, been commended or long / shortlisted in competitions. She founded Red Door Poets and her debut pamphlet, What the sheep taught me , is published by Live Cannon (2022).

64

Hell Mouth

High above the earth, where the little drone is safe to hover The red fire rages like a prison riot. Even at these heights It is impossible not to imagine the black plastic heating up. Moving in along the coastline, where the water is holding Its hand against the orange fray, a ketch is banking hard, Bringing it about and heading for home. A frantic boy runs From the edge of the woods and into the house, slamming The screen door and tossing a lighter into the kitchen trash. His neighbor’s parlor window is open and the sound of A marriage ending is flung upon the sidewalk and parts of The abutting yard. Some words cannot be unspoken. Like A cast iron pan mid air, they drop, they do not fly from the tongue.

Garrett Soucy

Garrett Soucy is a minister, writer and musician who lives in Maine with his wife and eleven children. His work has appeared in Forma , Plough, Theopolis and elsewhere. His book, Who is this Rock? (2018), analyses the literary motif of rocks and stones in the Bible.

65

Love Poem for the Twentieth Century

On Russian forces capturing the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, 24, February 2022

I’m a child again, searching the TV’s embers. A station is burning somewhere: on a map first, then, years later, vacant kitchens and classrooms—a fine dust collecting on sliding boards and swings. A blue fog can be seen shimmering from the pine after the flames. It creeps toward the couch where I sit with Mom and Dad, my brother and sister. We can’t know it’s arrived here unless fists of hair fall from our skulls and lesions bloom on our skin. I didn’t know this then, but I’m old enough to understand eyes, the panic flashing from them even when voices are calm. Mom and Dad can’t look away, so I can’t look away. The news says little, yet adult faces are pale as corpses. They are scarred creatures of the twentieth century. I drifted into the twenty-first light as ash, hoping for flights to Mars and cancer cured, but Stalin’s brutal mustache still burgeons, blast shadows still scream from the walls. And the station goes on burning. Remember the men with shovels perched on their shoulders? They filed in naked as newborns—meat to the microwave. It’s hot as a star in the station. The deeper they dig, the closer they get to a fragment of sun. Twentieth century, we miss you. How we wish we could quit, but here we are again, gazing into your coronal smile, longing for the lover’s suicide you promised before you goosestepped from our lives.

66

Brian Patrick Heston

Brian Patrick Heston grew up in Philadelphia. His first book, If You Find Yourself, won the Main Street Rag Poetry Book Prize. His poems have won awards from the Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Foundation and have appeared in Southern Review, Hotel Amerika and more.

67

Extradition of Drug Lord Dudus Coke: Barbican Girl Dash Weh Tivoli boy

Dudus / breath-taker of dutty yutes / preying on likkle girls’ cell phones and chochos / he pretzels politicians’ arms / so fathers can tief light to keep stoves on / his cash lines the bras of single mothers / who send their sons to your school / with their A*s / waves and clarks shoes /

prime minister bruce golding / approves Dudus’ extradition / your principal’s intercom interrupts lunchtime / year group becomes a herd of whispers / shuffling to collect bags / ears cock for loose lips on staff walkie talkies / everyone sprints to their drivers / your boy / shoves himself into a tivoli chi-chi bus / that mounts sidewalks to get him home / meanwhile / your barbican prado / cruises to water polo training /

at training / with every other stroke you glance at the plumes of smoke / from tivoli / in the distance / police helicopters chop your coach’s commands / three miss calls from your boy / usually you’re the needy one / you listen to his voicemail when you get home / jah know mi nuh know if me and mi family dem a guh mek it / if mi dead / and dem seh mi did shoot afta di police / a lie dem a tell /

meanwhile / in the name of President Dudus / tivoli gunmen buss shot after shot / not even a spot check for granny-less verandas / scrap vehicles and gas cylinders block cherry stain streets / your boy’s eardrums grind like pimento / his little sister and brother’s squeals stow in their kitchen cupboards / from his bedroom window he prees three of his bredrins plead the blood of jesus as they sit in their own / pooling / while rumours have it / underground / Dudus is a sewer rat / wearing a stiff wig for disguise /

the next day / prime minister calls for a state of emergency for tivoli / you neither adjust / nor die / but your boy vanishes / for a while / you ramp next to his empty desk / ask about his whereabouts / but not enough / in the tivoli community / mothers are graduating from sniffing foreheads / green armpits / to heaving at compost flesh / top lips marrying snotty nose-tips / single beds / open caskets

68

Courtney Conrad

Courtney Conrad is a Jamaican poet. She is an Eric Gregory Award winner and Bridport Prize Young Writers Award recipient, and she has been shortlied for The White Review Poet’s Prize, Manchester Poetry Prize and Oxford Brookes International Poetry Competition.

69

Shark Freedive in Swordfish Season

Shortfin Mako Shark, Isurus oxyrinchus. Red List.

The boys - I call them boys - are singing Cumpleaños feliz at the end of the headland. I am about to jump off into a swell.

Te deseamos t-I’ve jumped and the seaboys are beautiful. God this is fucking scary - and repetitive: countless fish, like twitchers’ LBJs. The sharks who come this way are makos and hammerheads. I think of sharks as boys. It’s their eyes: suppressed emotional trauma. 400 million years of it. We’re killing them of course. We’re killing every fucking thing. Nothing is being left unnetted.

When we were younger everyone thought I was the boy. What lovely girls you have and oh now a son. Later, the boys brought more boys to the house. It was a bungalow full of cats and adolescents: cockroaches lying on their backs, I’d flick their feet; they’d spin like B-boys.

I’m kicking lower and lower, discovering unfamiliar species, asking myself is that coral? like the ‘Is It Cake?’ Game Show where you guess before they cut into handbags, burger buns, steak. It’s almost always coral/cake.

There are fish here who turn from boys to girls once the alpha female dies. I keep going down, passing mating clown fish, the ceiling getting as high as a Georgian room. I am holding my breath, two beads of air in each nostril, gobstoppers: silverine, mercury.

I had to run-up for the leap, couldn’t just do it cold, had to throw myself, have my legs not stop me – running until my feet hit nothing.

I am remembering four years before this, wearing a VR headset, sat in Toni and Matti’s living room with their three boys; being lowered on their settee in a cage, searching for great whites –my feet and the grate, a letterbox gap, my limited front-facing eyes.

70

I am so far down now that I am calculating the time back to the top if I panic. I want the deer eyes on the side, the crabs’ on the end of their stalks, swivelling, or eyes in my feet to sense as octopuses do with the whole of their bodies, their entire skin seeing, responding. There is nothing here, then there is a face in front of me staring. Eye-fucking as they call it on the Tube. Snout / tail / snout / tail turning. So many commutes, I got eye-fucked before 9am. Sometimes, I was the one fucking them. I had hoped for a hammerhead, not a mako. Blueish, metallic, white - her skin and the sunlight thrumming across her scars. The mako and I are at the talking stage. Both of us might be in our 30s.

We are exchanging uncertainties. I find myself reciting Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class–Superorder–Order-Family–Genus–Species Equal tail – Sharp nose - Few. She is wondering: Will you - Are you - Should I – Deer eyes dilating. Run.

Anna Selby