6 minute read

The Puca and the Changeling

A short story by Madeline C. Lanshe

Once upon a time, a puca was bored, and that is never a safe beginning to any tale.

Rafferty seldom struggled to find ways to occupy his time. If he wasn’t bringing mischief, or blessings, (whichever the whims of the moment compelled him towards), to the people in the villages within his territory, he was riding the wind as a raven, hopping across lush, green glens as a hare, or terrorizing real hares as a hound. But one afternoon, so peaceful even the flies silenced their noisy wings and slept in the sun, Rafferty was struck with a boredom so strong he had the compulsion to rip all the black fur off his body.

Luckily (for him), a sound pierced the numbing peacefulness: a baby’s wail so sweet and melodious he had to put his hands over his long, droopy ears.

It had been a while since he’d conspired with a changeling, the creature responsible for the unearthly cries. Shifting into a slick, black fox he thought, This might not turn out to be such a dreadfully dull day after all.

In order to fully satisfy the itch for trickery in his heart, Rafferty decided to take the changeling babe, who joined him with equal excitement and even more villainy, to a village well outside his territory. The mortals within his territory had become too accustomed to his games, and now put their children’s cribs close to their fireplaces, with iron scissors just nearby, for protection. At the first sign that something was off with their son or daughter, they would immediately suspect the puca. And there was no fun in that.

Rafferty was a deft shapeshifter, and his horse form was ideal for galloping through the forest, keeping to the trees so as not to raise suspicion from farmers working in the fields. The changeling rode on his back, holding onto his long, wild mane.

It was Rafferty’s favorite time of day when they arrived at a distant village: night.

Rafferty shifted into his bipedal form. He’d need his three-fingered hands and opposable thumbs to let himself inside one of the homes. The changeling looped its tiny arms around his neck, draping off his back like a cape, as he crept through the sleeping village. He peered in each window with his all-gold eyes. As suspected, none of the babes were protected.

“We have our pick of the litter,” he said to the changeling, who gurgled a low laugh.

When they’d just settled on a tempting abode, Rafferty saw something moving out of the corner of his eye. It seemed he was not the only one drifting through the shadows with something resembling a baby; a stealthy woman was gently cradling the creature in her arms. Curiosity ignited, Rafferty followed her.

She stopped on the steps of the largest house in the village, just far enough from the other homes to set it apart. To Rafferty’s eyes, the tears she shed as she placed the babe at the foot of the door were glowing white: tears of pure love. She bent over, kissed the sleeping child on its forehead, and lifted the heavy knocker on the door, slamming it twice. Without waiting, she darted away.

The babe woke from the noise and, finding itself alone, began to wail.

Rafferty left the changeling in a nearby bush and crept up the steps to peer down on the infant. It was indeed human, and the mother’s tears still stained its forehead.

A noise from inside startled him and he quickly leapt onto the roof.

“What a horrible sound,” a man said, as the door to the house opened.

“It looks like someone has left their baby,” said a woman. “How inconvenient.”

“You’ve always said you wanted a child,” the man said to her.

“I want a beautiful baby girl,” the woman replied. “Not this dirty, screeching, frail thing.”

“Well then, I suppose we should leave her here,” the man said, not too concerned. “If we pick her up, even to move her, she will become our responsibility. Best to pretend we never saw her.”

“We’re not going to get any sleep tonight,” the woman complained as they closed the door.

Rafferty hopped off the roof and again looked at the babe. It was true that its cries were frightful. But then again, so was he sometimes.

“Come,” he whispered to the changeling, who crawled up the steps on its baby limbs.

“This is no fun,” it said. “No one cares about this welp. There is no excitement in replacing that which is not irreplaceable.”

“Ah, but you will make yourself irreplaceable,” said Rafferty. “And after some time, when the man and woman think they have been blessed, you will show them all the wickedness inside you, and they will wish, though they will not know you are not one and the same, that they’d taken the first babe.”

The changeling danced around gleefully on legs that would’ve been too weak to hold up a human baby.

“Get to work,” Rafferty said, “Before the wailing wakes the neighbors.”

The changeling stared at the baby, observing the lines and angles of its face. Concentrating, its bulging black eyes shrunk until they were little and blue, wrinkles smoothed and cheekbones rounded. The greenish hew of its skin turned ivory. In every detail, the changeling copied the human infant’s appearance, but enhanced it just enough so that it was the loveliest mortal child imaginable.

When Rafferty saw that it was done, he unwrapped the babe from the blanket and held it to his furry chest. He would not be able to run back to his territory as a horse this time. It would be a long, trying journey on two feet. The challenge excited him.

The changeling swaddled itself and lay faceup below the door.

“Wait until I’ve gone,” the puca said, and wobbled down the steps, the babe he was carrying now peculiarly silent.

He was hidden in the trees across from the house when he heard the same beautiful crying from his forest back home. He watched as the door again opened. The woman’s hand flew to her chest.

“What a radiant child!” she exclaimed to the man. “How is it that we did not notice her beauty before?”

“This is rather odd,” he said. “We must be properly exhausted.”

“No, I think our wish has been granted,” said the woman. “This is a reward for us being such generous citizens and for you leading the town so wisely.”

The woman bent over and lifted the changeling into her arms. It cooed innocently. But Rafferty could see the impish delight in its eyes and knew the mortals would never regret any decision more for the rest of their pathetically short lives.

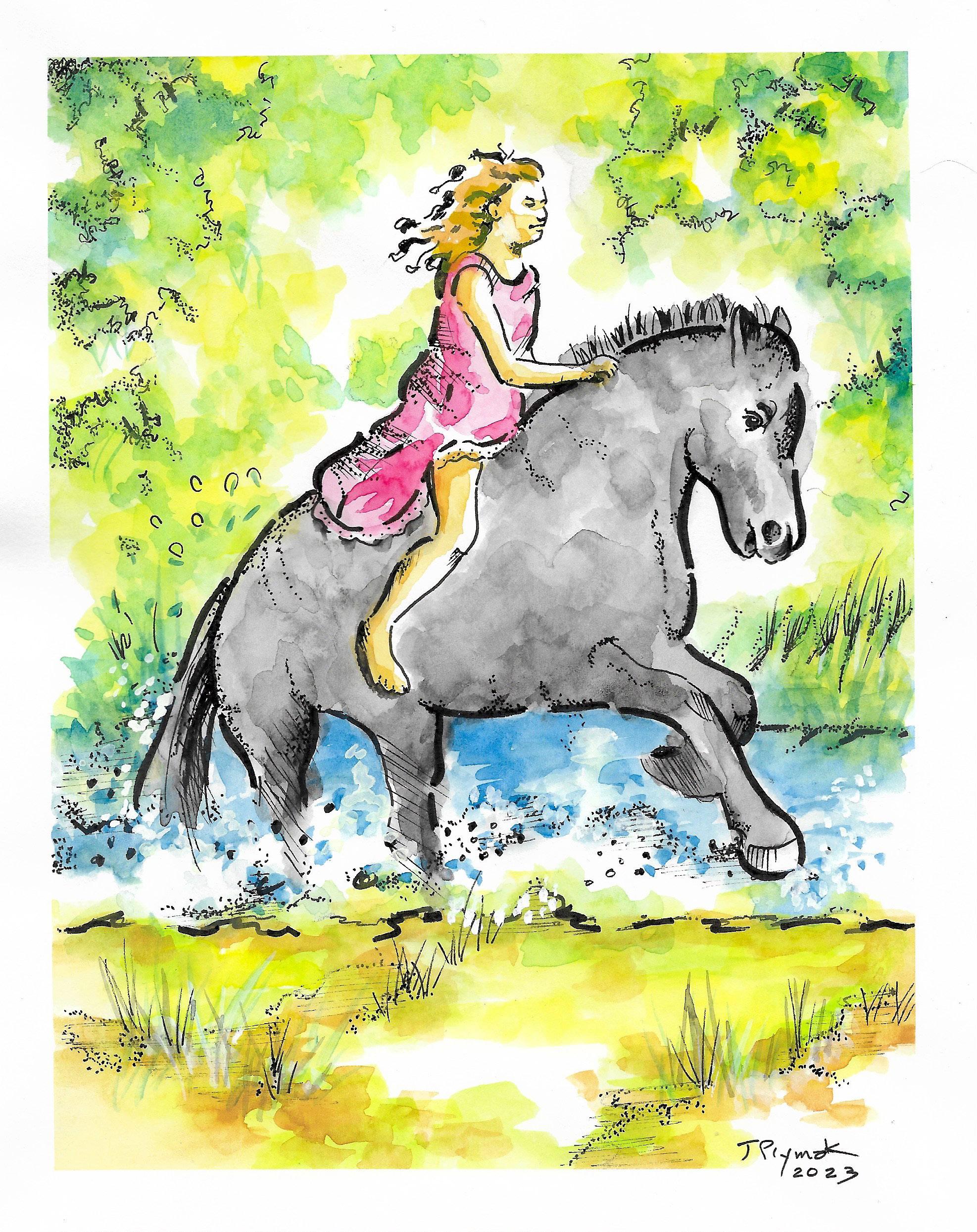

Keevy loved riding on Rafferty’s back through the rivers and streams, the sparkling water splashing her dangling legs and laughing face, her hair whipping around her like the twist of a tornado. Out of all his forms, Rafferty knew the stallion was now her favorite. Her preferences were ever-changing, just as he was. When she was a babe, she preferred, though she could not yet express it, his hound form, curling up between his massive paws while she slept.

That was what his nights had become. So occupied was he with the ever-growing human child during the day that, by night, he was too exhausted to scheme and meddle, preferring and enjoying, though he would not readily admit it, the cuddle time with the child, the child he never abandoned or gave up for the fae to turn into their servant as he’d planned.

As for the wealthy couple, though Rafferty would never see it, the changeling, who they’d named Aislin, aged them quicker than even the husband’s position in politics. Six years she’d spent beguiling them, the perfect, brilliant daughter and pride of the town. When she turned incorrigible, they could do nothing but endure her tempests of trickery and tantrums, hoping that it was only a phase she would outgrow. She wouldn’t, of course, because though her body grew and changed, her nature never would.

“Again, again!” cried Keevy, when Rafferty stopped to catch his breath, his large horse lungs working hard. Though he had never aged, and never would, something in the human girl’s giggles, dimples, and boundless energy kept him young..

“How about instead,” he said between breaths, “we create a little mischief, you and I?”

Keevy clapped with glee. “What shall we do today, Rafferty?” she asked.

As Rafferty recounted his not-so-diabolical plan to cover the rooftops of the village houses with flowers and turn all the pools and ponds gold, he thought about how he’d sat upon a much fancier roof one night and watched as the man and woman beneath him turned away the most precious treasure to be found, blind in a way only foolish mortals could be. But that was their loss. Rafferty didn’t need his puca eyes, which could see through darkness and into tears, to glimpse the worth that lay beneath the dirt and rags.

And so, Keevy grew up untameable and joyous, with a softness in her heart for all things wild and unwanted – Rafferty most of all.