30 minute read

Legal Feature

Restraints and non-compete clauses: an exercise in reasonableness

For dentists who operate under a contract with their practice owner, it is usual to expect that the contract will include a post-contractual restraint. That is, a provision which restricts the dentist’s conduct once they leave the practice. These may also be known as non-compete clauses

A restraint provision will typically provide that the dentist must not engage in activities that are similar to or in competition with those conducted at the practice; and there will commonly also be an express prohibition on the soliciting of patients. Dentists frequently enquire with us about whether their restraints are enforceable. This may be because a change of practice is imminent, or because they are considering future career plans; or in some cases, they may have already left their former practice only to receive notice that they are in breach of a restraint. Whilst restraints differ contract to contract, and their application and effect is always fact-specific, some general principles are explained below.

Restraints must be reasonable

The general rule is that a restraint of trade is contrary to public policy and void, unless it can be shown that the restraint is reasonable. A restraint must go no further than is reasonably necessary to protect the interests of the person in whose favour the restraint operates. Essentially, the courts will assess restraints based on commercial fairness and the need to hold parties to their agreements.

When might a restraint be valid?

When evaluating a restraint, the courts will look at circumstances which existed at the time the restraint was entered into. Matters such as the following, may be considered: • the respective bargaining positions of the parties; • the nature of the business and the industry in which it operates (including factors such as the level of specialisation and competition in the market); • the restrained person’s knowledge of and connection to the business, and the clients/patients of the business; • the length of time to re-establish client/patient relationships; • the seniority of the restrained person and their access to confidential information: A restraint applying to a practice principal will usually be more onerous than one applying to an association; • the impact of the restraint on the restrained person; • the length of time it would take or has taken to fill the vacancy created by the restrained person’s departure. For example, a restraint might be stated as applying within a 5km radius or (if that is not enforceable) a 3km or 1km radius; and similarly, for a period of 2 years or (if that is not enforceable) 1 year or 6 months.

It should be noted that the analysis of a restraint is highly fact specific. By way of illustration, in a 2014 Queensland case, the Court upheld a 15km radius and 18-month restraint for an experienced ophthalmologist; while in an earlier case, the same Court held that a 12-month restraint on a doctor was not enforceable because only 3 – 4 months were needed to find their replacement.

What are the consequences of breaching a restraint?

Typical remedies for breach of a restraint could include: • Damages and compensation for loss suffered as a result of the breach. • An injunction to prevent the restrained party from acting in breach of their restraint. Usually this will not be ordered if damages are an adequate remedy. Restraints can be a complex area. When including restraints in a dentist’s contract, practice owners

When might a restraint be unenforceable?

It is generally more difficult to enforce a restraint if it is drafted in broad and unreasonable terms. Grounds on which a restraint might be held unenforceable could include where:

• the clause goes further than is reasonably necessary to protect a party’s business interests; • the clause would deprive the restrained person from earning a living; • the restrained activity is not defined with specificity; • the restraint period and area are unreasonably wide. In some contracts, the area and period of a restraint may be expressed in a ‘cascading’ fashion to avoid the risk of having a Court strike down the whole restraint. should seek advice and/or use properly drafted restraint provisions. Conversely, dentists who are agreeing to a restraint or are already subject to a restraint should seek advice if ever unsure of the effect of that restraint.

© Panetta McGrath Lawyers 2020. Author: David McMullen. This information is intended as a general overview and discussion of the subjects dealt with. The information provided is not intended to be, and should not be used as, a substitute for taking legal advice in any specific information. Panetta McGrath is not responsible for any actions taken on the basis of this information.

The pursuit of happiness

By Colm Harney, Dentolegal Consultant at Dental Protection

On July 12, 2012, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution (A/Res/66/281) declaring every March 20 the ‘International Day of Happiness’ in recognition of the pursuit of happiness as an important human goal. According to Muthuri et al, happiness is characterised by experiencing positive emotions while simultaneously perceiving one’s life as meaningful and worthwhile. We all know that the practice of dentistry, while rewarding in so many ways, can also be stressful and challenging – especially when things don’t go according to plan in our interactions with patients, or clinically. At the same time, increasing awareness of burnout in our profession and acknowledging the importance of mental health, means that whilst we work to care for others, we must also care for ourselves.

In late 2019, just before COVID-19 struck, the Greater Good Institute for Health Professionals drew practitioners from all around the world to a three-day retreat. From this they formulated five key takeaways on how to cultivate your own wellbeing and happiness as a health professional.

Connection

Positive, kind and helpful connection with colleagues is the most under-appreciated source of stress resilience, wellbeing and peace. This ties in with the old adage that a problem shared is a problem halved.

Over my years of practice, I can think of so many occasions when I have shared a clinical conundrum or concern about a difficult interaction I’ve had with a patient – the longer I’ve been in practice, the more inclined I am to share and seek help. The mere act of vocalising the problem seems to immediately improve the situation (and often helps me to see a solution) and a sympathetic ear or advice from someone who has been there and done that is often all that is needed. Our profession, even in this age of social media, is still founded on oldfashioned values of collegiate spirit and experienced practitioners mentoring new graduates. The recurring theme in all of this is connection.

Gratitude

The institute also reported that “simple practices of gratitude do more than shift our wellbeing and outlook. They also ignite more kind and altruistic behavior”. That is not to diminish the anxiety and real consequences experienced by anybody due to COVID but more to accentuate how good we have it here relative to the rest of the world.

At the time of writing during the Covid-19 pandemic, here in WA we can carry out our work that we often take for granted, without fearing that the next patient interaction might have terrible consequences for us, our teams or our patients. This is truly something to be grateful for.

Empathy

The institute highlights research that has been replicated over many studies – “a measure of empathy can effectively inform clear-headed, compassionate care, which leads to better outcomes for patients and greater wellbeing and satisfaction for healthcare providers”. The caveat to this is that practice of empathy is a skill and a balance must be struck between “the kind of empathy that leads to distress or cynicism (both related to burnout) versus the empathy that leads to compassionate care”. Self-compassion

This is a big one for dental professionals – we are high achievers, working in small spaces where the tolerances between success and failure can be marginal. We are often striving for perfection, increasingly motivated by curated images of beautiful work we see on social media. “At the institute, participants talked about their harsh inner critic, who is continually comparing their performance to some ideal and evaluating them as falling short. Self-compassion is a practice of giving yourself kind, caring attention – the type you’d give to a friend or a loved one”.

Meaning and purpose

“Health care has intrinsic meaning because it involves helping others to be well." Psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl suggested that the search for meaning is the primary motivation for human beings.

In the context of happiness and search for fulfillment in our career it is worthwhile reflecting on why we go to work and do this difficult but rewarding job.

Does this align with what gives us meaning? Is it for monetary reward, seeing the patient’s face light up after having their smile transformed? Relieving pain, giving back to society or as a means to provide opportunities to do something we love in our spare time? Or perhaps simply providing for our families?

Understanding what values motivate us deep down and aligning this with what we do in our career, is a way to happiness and life satisfaction. In summary, the pursuit of happiness and the practice of dentistry need not be mutually exclusive. These five points can give a framework for reflection and analysis of what we do, how we do it, and the why sitting behind it all in order to find happiness in this rewarding and challenging profession.

REFERENCES Muthuri, R.N.D.K., Senkubuge, F. & Hongoro, C. Determinants of happiness among healthcare professionals between 2009 and 2019: a systematic review. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7, 98 (2020). https://doi. org/10.1057/s41599-020-00592-x Ekman, E. Five ways to protect your well-being as a health Care Professional. Greater Good Magazine. December 2019. Frankl, V. Man’s search for meaning: the classic tribute to hope from the Holocaust. Rider-Trade. 2008

How to Become an Employer of Choice

Recruiting and retaining talented employees can be difficult; however, becoming an employer of choice can assist in this process. While many employers believe that employees leave for better money, the reality is that most employees choose to resign for other factors, such as lack of job satisfaction, poor work-life balance, and lack of career advancement. This raises the question – what do employees want at work, and how can employers meet these needs and become an employer of choice to retain talented employees?

Employee turnover

Employee turnover is a pressing issue that practices may face. It is more efficient and cost-effective to retain a high-quality employee than to recruit, train, and onboard a new one. Turnover can cost practices a significant amount of money, affect practice performance, and cause poor job satisfaction in other employees due to staff shortages. Practices must therefore assess what steps it may need to take to ensure talented staff are retained. This involves looking at what is working, what is not working and implementing improvement strategies. This is commonly known as a retention plan. Practices should remember that employees do not choose an employer just once. In reality, an employee chooses the practice as a potential place of work, chooses to accept or decline an offer of employment, chooses to stay with the practice throughout their employment, and may choose to promote the practice as an employer of choice or refer friends, family, and colleagues. Practices must strive to be an employer of choice to attract and retain the best employees.

Attracting talented employees

To attract talented employees, a practice must have a detailed recruitment process in place. This starts with advertising the role strategically and include relevant information in the advertisement so that a candidate can assess their suitability for the role and whether the practice is a right fit.

Through the recruitment process the practice should also be able to demonstrate what it has to offer to potential employees. Employee retention is highly influenced by job satisfaction, and as such, potential employees want to know what the practice can do for them before accepting a role. When recruiting, practices should demonstrate workplace culture and values, career development programs and supports in place, and any other relevant factors which make it stand out from the crowd during the recruitment phase. Ultimately, practices should strive to be an employer of choice in all its actions, not just in the recruitment phase; however, the professionalism and nature of the recruitment process will certainly set up the practice and employee for success.

What is an employer of choice?

An employer of choice is an employer that maximises the full potential of their employees through effective recruitment, engagement, and retention. In general, the term usually refers to a good employer, which attracts and retains high-quality employees or is a leading place to work compared to others in the industry.

For further information or assistance in relation to the updated Health Professional and Support Services Award 2020, please do not hesitate to contact the ADA HR Advisory Service on 1300 232 462.

The essence of becoming an employer of choice is the quality of the employment relationship. Employers of choice foster a collaborative employment relationship, which focuses on the changing needs of both the employees and the practice, rather than a more traditional "us and them" approach, which largely prioritises the practice needs over the employee’s needs.

What do employees want?

If a practice intends to retain employees, it must be able to identify what employees want. Although money has some influence on whether an employee decides to take a position in a business, job satisfaction is what keeps an employee motivated, engaged and committed. So, what factors influence job satisfaction?

Employee satisfaction is highly influenced by purpose, wellbeing, and recognition. Employees report that Further to the desire for safety at work is the concept of psychological safety. Psychological safety is often defined as a belief that one will not be punished for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes broadly encompasses physical safety, mental health, wellbeing, engagement, and creativity. Research suggests that workplaces that foster psychological safety are more productive and have higher employee satisfaction and less turnover.

Psychological safety is a by-product of culture. Where people feel that their work is worthwhile, productive, challenging, and offers learning opportunities and development, engagement is improved.

In placing value in employee satisfaction, practices should undertake a holistic assessment of what their employees want. This may mean undertaking surveys, creating an open dialogue with employees and, creating new policies and procedures, including a recruitment or

they have greater job satisfaction when they perceive that their job offers them autonomy, security, future, and meaning. Autonomy means that employees want to feel valued, respected and like they can make a difference in the Practice. Security does not just refer to having job security but extends to feeling mentally, emotionally, and physically safe and secure at work. The idea of security at work further extends to employees wanting to feel that their job offers them a future, including career development and opportunities for advancement. induction process to ensure all employees have what they need to succeed. Studies have shown the most dangerous time for employee turnover is in the first few months of employment. Practices that focus on employee satisfaction right from the recruitment stage are more likely to retain talented staff. Practices should undertake steps to understand employee needs, including through surveys, ongoing dialogue, and positive workplace relationships. This will assist in becoming an employer of choice, and therefore increase the practice's ability to attract and retain talented employees.

Clinical ChallengesQuestion in Oral Medicine

Test your clinical knowledge with this issue's oral-medicine challenge

Dr Alissa Jacobs

Oral Medicine Specialist

Intra-oral photograph of lesion A 75-year-old male was urgently referred to me by his dentist for assessment of a large, painless mass extending across the left maxillary alveolus. The patient had recently had a fall, and attended for a new partial denture, and he noted that it no longer fit. He was otherwise unaware of the mass. Given the presentation, the dentist made phone contact to emphasise the urgency of the patient’s triaging.

His medical history was significant for cardiovascular disease; cardiac arrhythmia, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia. He had a pacemaker in-situ and was taking Amiodarone hydrochloride (antiarrhythmic) Bisoprolol fumarate (beta blocker), Rosuvastatin (HMG-CoA inhibitor), Aspirin and Eliquis (antithrombotic agents). He had a history of adenocarcinoma of the colon in 2005 treated with chemotherapy. He denied any other intervention for this malignancy and despite best efforts no other details were obtained. Clinical examination revealed a frail looking gentleman, without any obvious sign of ataxia or cachexia. Lymphadenopathy was not obvious on extraoral examination. Intraoral examination showed a mass measuring approximately 50mm in an anterior-posterior direction and 30mm transversely. The mass was erythematous and ulcerated, and the teeth involved demonstrated marked mobility.

Multiple incisional biopsies were completed across the lesion and the patient was sent for imaging; a CT extending from the diaphragm to floor of orbit.

In this case potential diagnosis is:

Hyperplastic tissue; due to an old and ill-fitting denture Angiogranuloma; reactive inflammatory response Squamous cell carcinoma; most common oral malignancy Oral melanoma; rare oral malignancy Metastatic adenocarcinoma; rare intraoral metastasis of his primary malignancy

Know the answer?

Turn to page 38 to see if you're right.

2

Dr Janina Christoforou

Oral Medicine Specialist

When dermal fillers go wrong

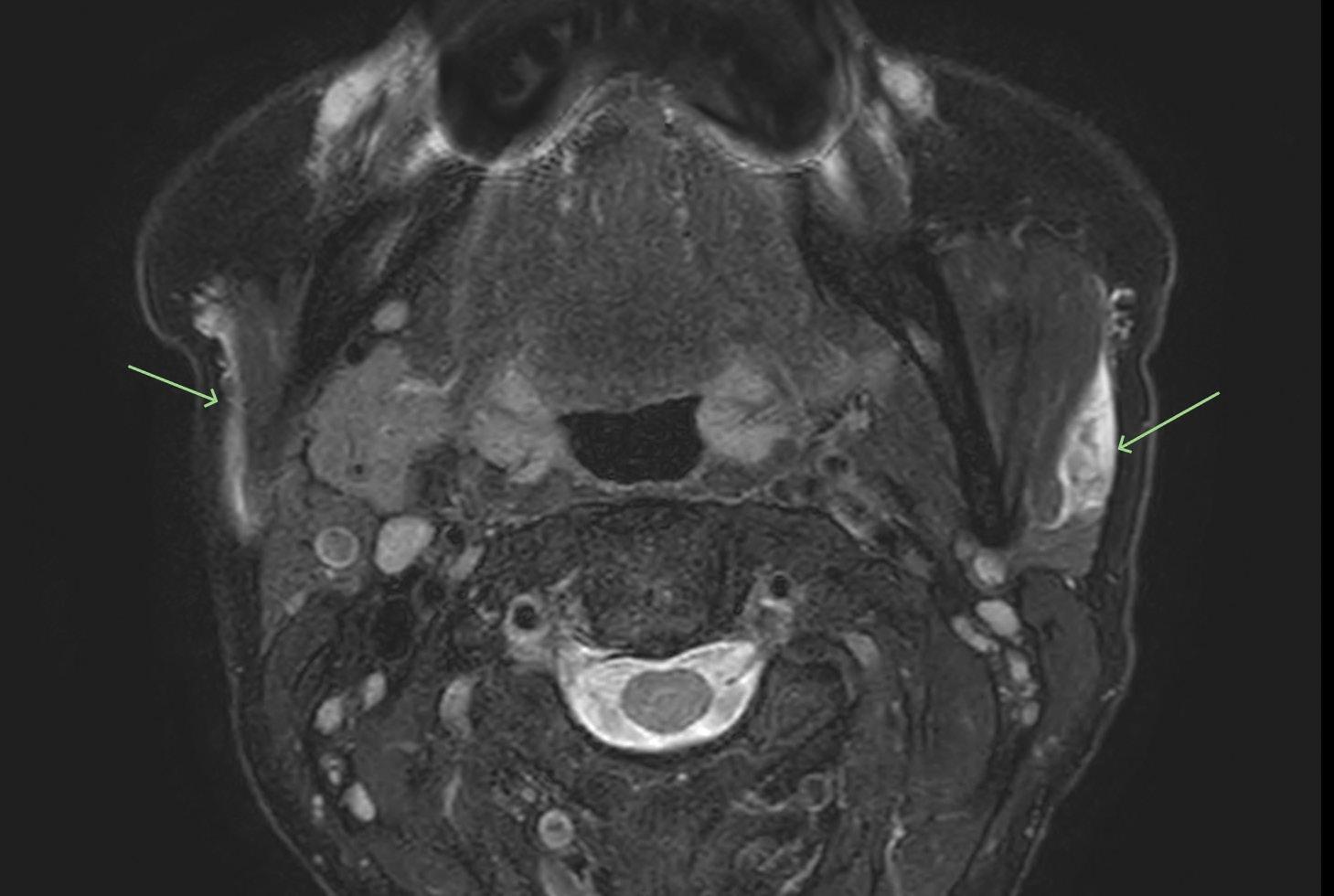

Arrows showing sites of cosmetic dermal filler

TAKE-AWAY MESSAGE

Dermal fillers incorrectly placed within parotid glands should form a part of the differential diagnoses of unilateral or bilateral facial swellings.

I previously wrote an article on delayed hypersensitivity reactions in relation to hyaluronic acid fillers. After recently coming across a patient with a facial swelling, I felt that it would be appropriate to discuss another potential complication which we should be aware of in regard to dermal fillers.

A 52-year-old lady approached their dentist with a left facial swelling and associated discomfort. A dental examination was undertaken, and the swelling did not appear to be of odontogenic origin. The patient was subsequently referred for further investigation. Clinical examination had shown a palpable, tender swelling over the left parotid region and there was no obvious secretion noted from the left stensen’s duct.

Non-odontogenic, unilateral swellings can arise due to a number of causes, such as sialolithiasis, sialadenitis, allergies, sinusitis, neoplasms, or trauma. An MRI was undertaken to further investigate the swelling and there was evidence of cosmetic dermal filler in the superficial lobes of both parotid glands, appearing subcapsular and juxtaparotid. This was more prominent on the left side of the face. The patient later disclosed that she had dermal fillers placed 1 week ago. Hence, the swelling was consistent with a parotitis. The swelling responded to a single course of amoxicillin. Nevertheless, there are times when hylauronidase enzyme injections are required to speed up the process of dissolving the hyaluronic acid filler.

The placement of dermal fillers is becoming very popular and hence we are likely to see more patients entering our clinics having had these procedures. Patients are often reluctant to disclose recent cosmetic procedures such as dermal filler injections. Hence, directly asking the patient is often required.

It is important to consider complications of dermal fillers in potential differential diagnoses of facial swellings. Much of the complications associated with dermal fillers arise from the incorrect positioning of the dermal filler in respect to anatomical structures. It would be advantageous to locate crucial structures and the position of the injected material post-injection by ultrasound investigation. Nevertheless, this may not be feasible for routine clinical application.

5

Dr Gaurav Vasudeva

Specialist Endodontist

info@endopractice.com.au

Fig1: Showing independent middle mesial canal in the 1st image and the middle mesial merging with the mesio-lingual in the 2nd image.

Anatomy of the Root Canal System & its Clinical Implications

Mandibular Permanent Molars

This is the final installment of Dr Gaurav Vasudeva’s five-part series on the anatomy of the root canal system. Read the previous four articles in the Western Articulator.

PART 1: May 2020 PART 2: June 2020 PART 3: Sept 2020 PART 4: Dec 2020/Jan 2021

In our final article for the series on anatomy of root canal systems, we will discuss the mandibular molars and some further insight to ‘C’ shaped canal systems that are more specific to mandibular 2nd molars. Mandibular molars were always considered to have a less-complicated root canal system in comparison to their maxillary counterparts, but recent micro-CT studies show elusive middle mesial canals and complex C-shaped canal anatomy; although not prevalent it can provide challenges without having the knowledge of their presence and locations.

Unlike the maxillary molars that are difficult to read through the periapical radiographs, mandibular molars can be visualised better – exceptions being C-shaped canals and radix entomolaris (additional distal root) although presence of the inferior dental canal fairly close to the apices of these molars can create some difficulty. Precautions need to be taken while cleaning/shaping and obturating the apical 3rd of these teeth.

We will discuss some C-shaped canal configurations in more detail due to their highly variable configurations and its marked racial prevalence. Such canals are prevalent in about 16% of mandibular 2nd molars as a whole but can be up to 30-40% of the mandibular 2nd molars in people originating from east and south east Asia.

C-Shaped Root Canal System:

In the last 10 years, there have been few studies that have provided a thorough assessment of the C-shaped root canal configurations. However, the initial attempt to classify this unusual anatomical finding and its particular irregularities was addressed by Melton in 1991 and was characterised as follows.

Fig 2: Mandibular 1st molar with 5 canals including an independent middle mesial. (a) Preop #36 with symptomatic apical periodontitis (b) All 5 canals with files for WL confirmation (c) Image of all canal orifices (d) Post obturation radiograph (e) Post obturation with distal angulation revealing all 3 mesial canals (f) Post obturation image of the access.

• Category I: A continuous C-shaped canal that flows from the pulp chamber to the apex delineates a C-shaped outline without any separation. • Category II: A semicolon-shaped orifice in which dentin separates the main

C-shaped canal from one distinct mesial canal. • Category III: Those anatomies with two or more discrete and separate canals with a: (1) subdivision I, C-shaped orifice in the coronal third that divides into two or more discrete and separate canals joining apically; (2) subdivision II, C-shaped orifice in the coronal third that divides into two or more discrete and separate canals in the mid-root to the apex; and (3) subdivision III, C-shaped orifice that divides into two or more discrete and separate canals in the coronal third.

a

b

Fig 3: (a) Milton’s Classification of C-shaped canals. (b) Fan et al 2004. Classification of the C-shaped canal system that was further modification of the Milton’s classification.

Fig 4: 3D classification of C-shaped canal configuration. (a) Merging type; (b) symmetrical type; (c) asymmetrical type (Gao et al)

Fig 5: C-shaped canal system with an independent MB canal whereas ML and D canals are fused in a C shaped anatomy. (Classification C2)

Fig 6: Another C-shaped anatomy where all 3 canal systems are connected and merge at the apex but have separate orifices. The next major classification system presented took advantage of the newer technology with the application of extensive micro-CT sections. With some new anatomical information, Fan et al. modified Melton’s classification as follows:

• Category I: The shape of the canal was an interrupted “C” with no separation or division.

• Category II: The canal shape resembled a semicolon resulting from a discontinuation of the

“C” outline; however, either angle created should be no less than 60°. • Category III: Two or three separate canals were present and both angles created were less than 60 • Category IV: Only one round or oval canal was present in that cross section. • Category V: No canal lumen could be observed (usually seen near the apex only) in this variant.

All clinical cases performed by Dr Gaurav Vasudeva and published only for the purpose of dental education. Please contact the author for references at info@endopractice.com.au

1st Molar

PERMANENT MANDIBULAR

Complete Root formation 9.2-10 years

Number of roots 2 (92.2% independent; 5.3% fusion), 3 (2.5%) 2 (86.9%), 3 (12.5%) 1 (0.55%) 2 (independent 39.2%; bifurcation at the middle third 31.8%; fused 26.7%) 3 (2.3%) 4 (0.2%)

Number of root canals 2 (8%), 3 (56%), 4 (36%)

Apical Foramen position M, central 22%; lateral 78%; D, central 20%; lateral 80%

Accessory canals M: 45% (coronal, 10.4%; middle, 12.2%; apical, 54.4%) D: 30% (coronal, 8.7%; middle, 10.4%; apical, 57.9%)

Apical ramifications (delta) 19.4%- 30.9%

C Shaped Canal 0.53%

Anomalies Five canals; six canals, seven canals, radix; taurodontism, apical curvature; gemination/fusion; isthmuses, three roots; C-shaped; middle mesial canal; middle distal canal

Clinical relevance • It usually has two roots, but occasionally it has three, with two or three canals in the mesial root and one, two, or three canals in the distal root. • The distal surface of the mesial root and the mesial surface of the distal root have a concavity, which makes the dentin wall very thin.

• The presence of root canal isthmuses averages 55% in the mesial root and 20% in the distal root; multiple accessory foramina may be present in the furcation area; the dentin overhang at the mesial orifice must be removed to lessen the danger of penetration.

2nd Molar

PERMANENT MANDIBULAR

13.8-14.8 years

2 (16.2%), 3 (72.5%), 4 (11.3%) 1 (12.5%)

M: central 19%; lateral 81%; D: central 21%; lateral 79%

M: 49% (coronal, 10.1%; middle, 13.1%; apical, 65.8%) D: 34% (coronal, 9.1%; middle, 11.6%; apical, 68.3%)

17.5-35.7%

16.33% (1.9–44%)

One canal; two canals; five canals; apical curvature; gemination/fusion; isthmuses; C-shaped, middle mesial canal

• This tooth is very similar to the first molar; however, the roots are shorter, the canals are more curved, and the range of variation is higher. It may have one to five canals, although the most prevalent configurations are three and four canals. • The two mesial orifices are located closer together; a relatively common variation in root morphology is the presence of C-shaped canal. • Clinical signs of the presence of

C-shaped canals include continuous pain and persistent bleeding from the root canal and confluent canals.

• The apices of this tooth often are closed to the mandibular canal.

Clinical ChallengesAnswer in Oral Medicine

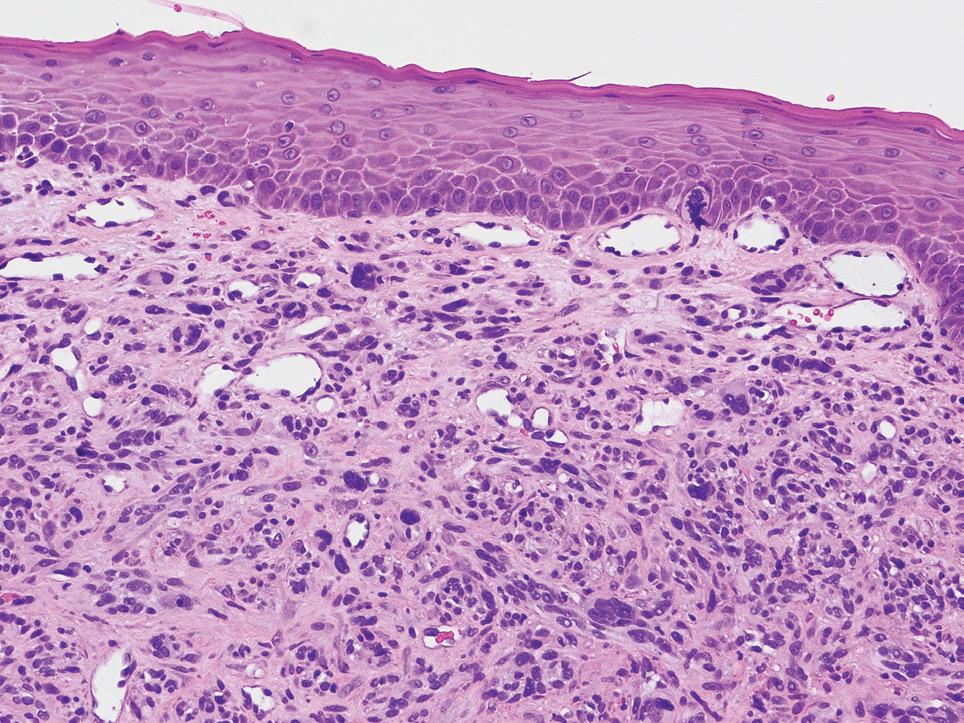

The correct diagnosis was:

Oral melanoma; rare oral malignancy

1 2

The lesion in question was histologically proven to be an aggressive oral melanoma. Although oral melanoma is rare, pigmented lesions in the oral cavity must be viewed with a high index of suspicion. In this case, the lesion did not contain any pigmentation and was amelanotic. Amelanotic melanomas of this size are exceedingly rare. Histologically, the lesion itself was highly dedifferentiated and multiple stains were relied upon to ascertain the diagnosis. In this instance the lesion could have very well been one of the afore-mentioned differentials and biopsy (with appropriate staining) is key to the diagnosis.

The patient’s imaging showed a large heterogeneously enhancing partly necrotic mass centred on the left maxillary tuberosity and adjacent posterior maxillary alveolar ridge, with superior protrusion into the posteroinferior aspect of the left

3 4

5

maxillary antrum, extensive aggressive erosion of the maxillary tuberosity and anterior extension within the left maxillary gingivobuccal sulcus and along the left lateral margin of the hard palate. No suspicious lesions were noted elsewhere he was sent for urgent management to his designated tertiary hospital. He was seen in a multi-disciplinary team with the plan of surgery and immunotherapy (Keytruda) as the first line option.

The dentist has played a pivotal role in giving this patient the best chance of survival. By picking up the lesion, realising the urgency and calling on the patient’s behalf to ensure his case was bought to my attention. This meant that the patient was seen, diagnosed and staged promptly.

6

1. Low power amelanotic melanoma 2. High power amelanotic melanoma 3. CT showing the extend of the lesion. 4. CT showing the extend of the lesion. 5. SOX10 showing strong diffuse staining 6. HMB45 showing patchy positive staining

Histopathological imaging: Courtesy of Dr Jason Lau, Anatomical Pathologist, Clinipath Pathology

Radiographic imaging: Courtesy of Perth Radiological Clinic

References available by email: alissa@pomds.com.au

Eat Play Sleep

ADAWA member Dr Rob Norris has published a book about health and wellbeing – transforming his own health in the process. We spoke to him about the achievement

Eat, Play, Sleep answers many of the questions patients regularly ask in a language the average person can understand. The book is written to break down the science for the general reader with solid facts and plenty of comic relief to explain and maintain interest. According to Rob, we all have a book inside us waiting to get out. With publishing a book on his bucket list, Rob says he thought it would be much easier to achieve than walking the Kokoda Track.

Rob was inspired to write the book after attending a CPD lecture at ADA House, where the presenter (a physician) spoke about the prevention of systemic disease, to maintain our 21-year-old body size into our seventies and beyond. This became Rob’s goal.

Another ‘kick in the pants’ for Rob to look into these health and lifestyle changes was the diagnosis of prostate cancer. The book took around three years to complete. “I started this version in May 2017, or shortly after. I had spent some months previously on a manuscript that explained the evolutionary reasons for our behaviour and physiology,” Rob recalls. “It was awful, so I deleted it to avoid future embarrassment. I have a dear friend who is a retired Naval Officer; he told me that books are never completed, they are abandoned. “My book was probably ‘finished’ in September 2018 and should have been out for Christmas that year, but I fiddled with it endlessly, making incremental improvements. In November 2019 it went to my editor who, in a matter of weeks, fixed my manuscript in a way that would have taken me a lifetime.”

The final result – Eat Play Sleep: Three Keys to Finding Your Younger Self – investigates the importance of sleep, activity and food, with many humorous memories, personal experiences and patient stories shared along the way. The book is divided into three sections:

• Part One: Sleep to Health, Snooze and Lose the Ooze (where Rob covers sleep basics and sleep disorders) • Part Two: Active Life – Strength and Motion (using energy and being active) • Part Three: Food Glorious Food (nutrition for starters, are you what you eat? The main course)

As someone who was relatively active and ate well, there were some surprises for Rob when researching ways to find your younger self that made a big difference to his own health and wellbeing. About Rob Rob Norris practices in Wagin, south-west WA. In his spare time, he reads, writes, brews prize-winning beer and drinks it, and watches cricket and F1. If he wasn’t a dentist, he says he probably would have gone into teaching, and dreamed of being a historian or archaeologist.

“I battled unsuccessfully with the incremental weight gain,” he recalls. “I had good eating and exercise habits. I probably had better habits than they are now, but my sleep was short and poor. When I corrected my sleep I felt better, had more stamina and the weight seemed to fall off in a matter of months.”

Rob is a real example that the common-sense approach ideas in the book works – he is now the same weight and trouser size that he was aged 22. He says since making the changes to his lifestyle he is feeling pretty good. “I have not felt this well since I was in my late 40s; 15 years ago,” he says. “I feel fitter, have more stamina and have noticed positive changes in attitude.”

Rob recommends living better, healthier lives to his dental colleagues. “Dentistry can be a very demanding vocation,” he explains. “Many of us work single-handed and for long hours. We are required to concentrate and focus on delivering a high-quality service – perhaps for those who are not always the most compliant subjects. “When things go wrong, we need to have the resilience to deal with the situation in a timely and professional manner. We owe it to ourselves, our families, and our patients to be the best version of ourselves to deliver the required professional service.”

Rob also hopes readers pay more attention to the quality of the information they use to form opinions. “There is a thread of not-so-subtle cynicism running through the book,” he says. “If a reader changed just one or two actions for the better, it would be a good result. Alternatively, if they simply had a laugh at some of the passages and recommended the book to their pals, I will be delighted.”

You can purchase Eat Play Sleep: Three Keys to Finding Your Younger Self by Rob Norris, from Amazon: amazon.com/Books-

Rob-Norris/s?rh=n%3A283155% 2Cp_27%3ARob+Norris

Putters at the ready

The WADA golf season commences in February, with our traditional first game at the magnificent Royal Fremantle Golf Club. WADA golf is available to all interested dentists and dental industry representatives. We meet regularly throughout the year, on a Friday afternoon, for a competitive round of golf, at various courses throughout the Metropolitan area. Golfers of all standards are welcome to participate. An official golf handicap is preferred, and budding golfers will be assisted to obtain an official handicap as required. Fellowship, relaxation, and an afternoon away from the drill and fill is what you can expect when you join our friendly group. New participants are most welcome. Should you wish to participate in any of the games this year, please contact me at dentistgolf@gmail.com for more information, or to be included on our mailing list. Our fixtures for the rest of year are as follows:

March 26 Gosnells Golf Club May 5 Hartfield Country Club June 18 Joondalup Resort Aug 6 Royal Perth Sept 17 Cottesloe Golf Club Oct 20 Country Trip Nov 19 Lake Karrinyup

Good golfing,

Michael Whitford

WADA Golf Captain

dentistgolf@gmail.com