12 minute read

The Importance of Being Sherish

from Sherry

I am indebted to my old friend the eminent wine historian Charles Minoprio MW, for his brilliantly quirky, if sometimes alternative, take on the beginnings of sherry:

‘Wine production in Jerez actually predates the Roman occupation. It was shipped in amphorae to Rome, which proved the beginning of outsider interference with the sherry trade. The wines were so good and plentiful that, in AD 92, the ruthless, egotistical Emperor Domitian ordered the grubbing up of the vines [likely in favour of more practical cereal crops] as he had done in Gaul. The order was rescinded by Emperor Probus in AD 283. As in France, the growers were quite adept at avoiding these little irritations, but it was the taste of things to come. The Romans stayed until about AD 409. Was it the sewage system, immigration or the Brussels type bureaucracy that did for them? The Vandals stayed just long enough, 20 years, to name Andalucía – Vandalucia. This is, I think, disputed, but seems good to me. They were supplanted by the Visigoths – allies of Rome – who became Christian, but increasingly decadent until they were kicked out by the Moors in AD 711. Their arrival began a period of artistic civilization, possibly unique in European history.’

The Moors (north African Arabs, or Muslims), rulers of Sherish from 711, ensured that vineyards were replanted and cultivated. There was a slight hitch in 966, according to Charles Minoprio, when:

‘The Caliph had one of the periodic fts of religiosity that used to affict the Vatican when discussing the lucrative business of concubinage, and consequently viticulture was banned. The growers argued that their grapes were needed to feed the army, and continued to grow them in a rather subdued way until the hard-line Caliph passed away.’

Left: Bacchus, the Roman god of the grape harvest. The Romans undoubtedly enjoyed the wines of Jerez, which they knew as ‘Ceret’. Evidence of their presence in the region abounds. (Statue from the Louvre, Paris.) Right: Seville’s Alcázar – its upper foors still inhabited by the Spanish royal family – is built on the site of a Muslim fortress. Its striking Moorish architecture inspires visitors and historians alike.

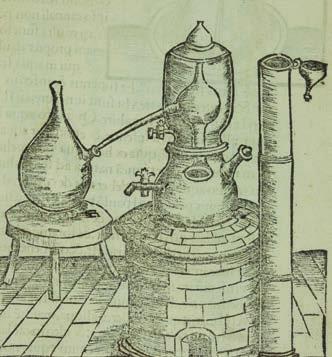

The Moors introduced the alembic for distilling wine – the distillate was used to fortify sherry so it would become stable enough to transport.

King Alfonso the Sage – a 13th century believer in the quality of ‘sherry’ wines. Muslims are famously teetotal, but doubtless relished growing vines to provide grapes and raisins for the table and for medicinal purposes. They were also happily tolerant of Christians and Jews, who certainly enjoyed a copita or two. Moorish domination gave Andalucía a period of expanding wealth. The Muslim legacy of architecture and buildings is still present for all to see and enjoy today. Cue the Alhambra in Granada and the Alcázar in Seville. These are as remarkable achievements, both architecturally and innovatively, and have inspired Spain’s determination to maintain its heritage. It was within this creative atmosphere that the vineyards around Jerez, the most southern in continental Europe, thrived. The wine produced may not have been sherry as such, but as the vines multiplied, so the prosperity and confidence of this agricultural population grew. This was immediately recognized by King Alfonso, who in 1269, just five years after the Christians moved in, granted Royal Arms to Jerez. Alfonso the Sage, as he was affectionately known, actively encouraged the cultivation of the vine. He personally spent time in the vineyards and recognized their quality. This royal patronage helped define the wines of Jerez. Sherry was born. This confidence continued unabated throughout the Christian era. As Chaucer described in the Pardoner’s Tale: ‘This wine of Spain creepeth subtilly’. He also tells of the ‘fumositee’ of the wines of Lepe – a coastal Andalusian town 112 kilometres to the west of Jerez, beyond the Sherry Triangle. He confirmed the strength of the wine by saying that ‘if you drank too much, you would not know whether you were in Cheapside or Lepeside’. The Moors had also introduced the alembic, a simple pot still, which enabled the Spanish to distil wine for the fortification of sherry. Once fortified, the wines became sufficiently stable to enable them to be shipped to the important English market. The first recorded shipment of sherry to England was in 1340, nearly 700 years ago. Perhaps the fact that King Edward III had declared war on France in January of that year had accelerated the demand for wine from other countries, one of which was Spain? Quite remarkably, the vinous association between Spain and England has survived – despite the occasional battle and some ill-advised sacking – ever since this time. No country has been more faithful in its reverence for sherry than England. And even though the current consumption figures have taken a considerable knock, it isn’t the first time this has happened, as we shall see.

In 1380, King Juan I granted the privilege of adding ‘de la Frontera’ to several border towns and cities in recognition of the sterling work that the inhabitants had achieved in keeping out the Moors. A century later, in 1482, the influential coopers’ guild stipulated that the capacity of the sherry cask, the universally recognized sherry ‘butt’ – from the Spanish bota – must be fixed at ‘30 arrobas’, which translates to 500 litres. An aroba is a measure of grapes by weight, around 11.5 kilograms, or a measure of wine by volume equivalent to 16.7 litres. Somewhat incredibly, this exact measure of grapes and wine is still in play today. And happily prescient of future quality control regulations, the coopers also decreed that the butts ‘must be cut and assembled with good wood that was not tainted by fish or oil’. This period in Spanish history is notable for the extraordinary maritime voyages of ‘fearless sea dogs’. Italy’s Christopher Columbus and Portugal’s Ferdinand Magellan both gathered their trusty sailors from Andalucía. Columbus famously discovered America in 1492 and in so doing, established Sanlúcar de Barrameda – the coastal town just 14 kilometres from Jerez – as a major port for this new American trade. In 1519, Magellan, on setting out to circumnavigate the world, famously spent more on sherry (probably fino) than on armaments. He obviously knew how to keep his crew happy. It may be an exaggeration to say that the 16th century was sherry’s sweetest hour, but this time span was certainly influential in spreading the

During the Age of Exploration the ports of Cádiz and Sanlúcar de Barrameda were the starting points for many voyages to the New World and East Indies. On many of these voyages, stocking up on ample supplies of the area’s wine was considered a necessity. Christopher Columbus almost certainly had sherry with him on his voyages to America, which makes sherry, in all likelihood, the frst wine brought to the New World.

Fewer Vineyards , more Pagos

One of the contradictions of sherry – which is after all one of the most recognizable wine names in the world – is how little is known about its vineyards. Wine enthusiasts have instant recall when it comes to vineyard names in Burgundy or Bordeaux, but far less when it comes to port and virtually none when it comes to sherry or Champagne. Yet as the wine critic Tim Atkin MW reminds us, in the 19th century, Jerez’s Macharnudo Alto vineyard was as famous as Burgundy’s Clos de Vougeot or Germany’s Bernkasteler Doctor. It is not that vineyards do not matter in Jerez or Champagne. They do. It is more that in these two wine regions, the vast majority of wines are a blend of different years, so there is little hype or angst about a particular vineyard in a particular year. Champagne and Jerez have more in common than might first appear. Both are white wines; both produce delightful dry aperitif wines; both produce excellent rich dessert wines; both wines need long maturation to achieve their own special characteristics; both regions focus on brands rather than vineyards and, crucially, both regions share the same chalky soil benefits. Champagne is made from the Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier grape varieties, whereas Jerez relies almost exclusively on the Palomino grape, with a touch of Moscatel and Pedro Ximénez. Champagne sparkles while sherry is fortified. But what clearly unites them is that these two wine regions – one in northern France and the other in southern Spain – produce, arguably, the finest, most refreshing and most satisfying aperitif wines in the world. The key lies in the white, chalky, calcium carbonate soil, which ensures the vital acidity in both these wines. In Champagne, this soil type retains moisture, giving the grapes a built-in humidifier, which enables them to become rich in nitrogen. Underground cellars have also been more easily hewn out over the centuries. It is this same stretch of soil that, followed to the west, shows itself in the white cliffs of Dover. Farther along the south coast of England, this happy soil strata pops up in Kent, Sussex, Surrey,

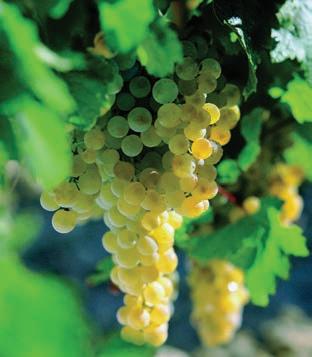

Hampshire, Wiltshire, Dorset and Cornwall, providing wonderful opportunities for English winemakers to grow their own fizz. Walking through top quality sherry vineyards, the chalky soil may not always be apparent, but deep down, it is there. In Jerez it is called albariza, and the best vineyards – those in the Jerez Superior region – are composed entirely from it, in many cases down to a depth of six metres. In the summer, this same white chalky soil helps ripen the grapes by reflecting the sun’s rays onto the underside of the bunches of grapes. Albariza soil can also absorb as much as 34 percent of its weight in water, which is a welcome trait in this dry landscape. With an average of only 600mm of rain each year in Jerez, it is vital to make maximum use of any moisture available. When dried by the sun, the albariza shines and reflects; when washed by rain it becomes slippery mud, but once the sun is out again it reverts back to its natural state. All this contributes to an essential equilibrium in the vineyards. Albariza contains limestone and, as in all quality wine regions, it is this sub-soil that is the key to the vine’s nourishment. There is evidence that the first classification of vineyards was in 1740. At that time there were 12 different types of albariza soil listed and 14 different grape varieties. This was not unusual as the more varieties, the healthier the insurance if one or more underperformed at harvest. It also allowed for greater blending opportunities to achieve the best result each year. The practice was similar for Tokaji and for port – and as with sherry, many fewer grape varieties are being planted now for these wines. The dreaded phylloxera virus changed everything. To survive it, vineyards had to be replanted with disease-resistant rootstock, and Palomino (the best grape for making sherry) was almost uniformly the growers’ choice. Nowadays, virtually 98 percent of all sherry plantations feature Palomino grapes that have been bench grafted onto American roots that are not affected by the phylloxera louse. There are constant experiments with different Palomino clones, to help eliminate diseases such as fan leaf. (The current favourite seems to be the California clone, combining high quality with high yield.) And cordon pruning is an important factor in the overall quality stakes, controlling the vigour of the vines so their grape yield is lower, but higher in concentration.

Left: Palomino grapes are the mainstay of Jerez’ vineyards; their juicy, low-acid fruit and delicate character makes them a perfect base for making sherry. Right: After the phylloxera epidemic of the 1890s most of Europe’s vineyards had to be replanted with vine cuttings that were bench-grafted (as pictured) onto disease-resistant American rootstock. This clever vineyard tactic is now common practice.

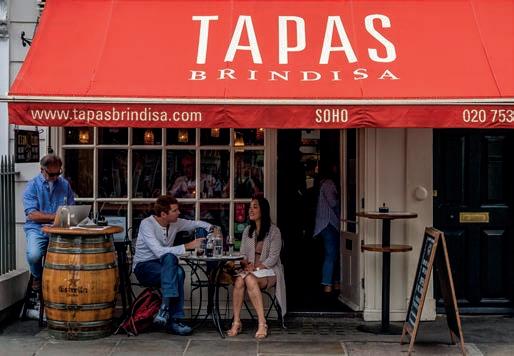

styles of sherry. This took time, but now the menu takes leadership from the sherry styles. A new Tabanco branch opened in Cambridge in March 2019. This is a big step forward for sherry, which now accounts for 25 percent of the bar’s wine sales. The emphasis is on informality. This is helped, as in most tapas bars, by most dishes or plates being priced at or below the £10 point. The fact that you may well enjoy two or three of these plates somehow does not enter the little grey cells. The enigmatic Hart brothers, Sam and Eddie, have four branches of their Barrafina bars. Their concept of open kitchens, bar seating and no reservations combined with excellent smiley service, hits the spot. Served chilled in proper glasses, the sherries that accompany the dishes in these delightful surroundings are invariably from the boutique bodega brigade – plus the sherry masters, González Byass. Salt Yard, which also trades under the names Dehesa and Ember Yard, is run by Sanja Morris and Georgina Laing and adds happily to the tapas scene in London. It has to be said that almost all of these outlets admit that they sell far more wine than sherry, but it is the sherry that gives gravitas. Boqueria’s two branches are equally fun to visit. They have nine sherries, which is enterprising, but what is surprising is that four are dry styles and five are sweet or dulce styles. Apparently, the British consumer is still not totally on board about the myriad of manzanillas, finos, amontillados and palo cortados that offer such delight and value. Sherry still vies with port as a drink for dessert or after food. The outlets with by far the most enterprising and exciting range of sherry – carefully selected by Peter Dauthieu – by the glass and by the bottle, are within Abel Lusa’s expanding empire, and include such enticing names as Capote y Toros, Tendido Cero and Tendido Cuatro. These are modern and friendly bars where the fortunate consumer has over 50 sherries to choose from. Almost a full time job. All these dishes and tapas allow the different styles of sherry to complement them in their natural habitat. Food pairing is relatively easy. It is the different styles of sherry – manzanilla, fino, amontillado, palo cortado, oloroso and PX – that create sherry’s strengths as a natural food pairer. In basic terms, a manzanilla or fino favours fish and asparagus; an amontillado goes best with nuts, smoked fish and soups; a palo cortado or oloroso with game, tuna and cured cheese; cream sherries with foie gras and fresh fruits, and PX with ice cream, chocolate and blue cheese. Sherry is closer to the table than

Here, at Brindisa’s Soho branch, fresh, authentic tapas are served alongside sherry. As proprietor Monika Linton says: ‘Brindisa was born on a shoestring with a box of cheese.’ But times have changed since those unknowing 1980s days. Business is buzzing now.

Left: traditional Spanish tapas are served in restaurants and bars for sharing with friends.