10 minute read

Introduction

from Sherry

I ntroduction

The mini skirted 1960s and the kipper ties of the 1970s saw the heyday of sherry. Tutors and dons, vicars and grannies all broke social ice by uttering the immortal words: ‘Would you like a glass of sherry?’ While Bordeaux, burgundy and port were all struggling to get back on their feet after the war, sherry sailed majestically on. Jerez, in Andalucía, was the destination of choice for wine visitors. Jerezanos knew how to produce wine and how to party. Their hospitality was as delightful as the chilled finos that they seem to consume 24/7. They were the first vinous playboys. Sun, Flamenco, horses and bullfighting all contributed to the sherry paradise in southern Spain. To paraphrase Harold Macmillan in another context in July 1957: ‘They’d never had it so good.’ Gradually, it all started to collapse. For the past 30 years or more, sherry volumes have been inexorably in decline. This was partly due to the rise and rise of ‘wine by the glass’, the fashion for Chardonnay and the resultant old-fashionedness of sherry. More pungently, it was the result of a single man, a local boy gone bad. A local boy who bit off more than he could chew and became as powerful as the Spanish government itself. A man who lost it all and, in doing so, was responsible for the devastating decline of this once great wine. That such an industry, such a source of pleasure, could virtually collapse is hard to believe. That it was all the fault of one man is even harder. But José Maria Ruiz-Mateos, convicted and jailed in 1985 for fraud, bamboozled even the greatest names and ran his vast empire, largely composed of prestigious sherry bodegas, into debts of over two billion euros. Sherry has yet to recover – the business, that is, not the quality of the wine, which under intense pressure has soared to new heights.

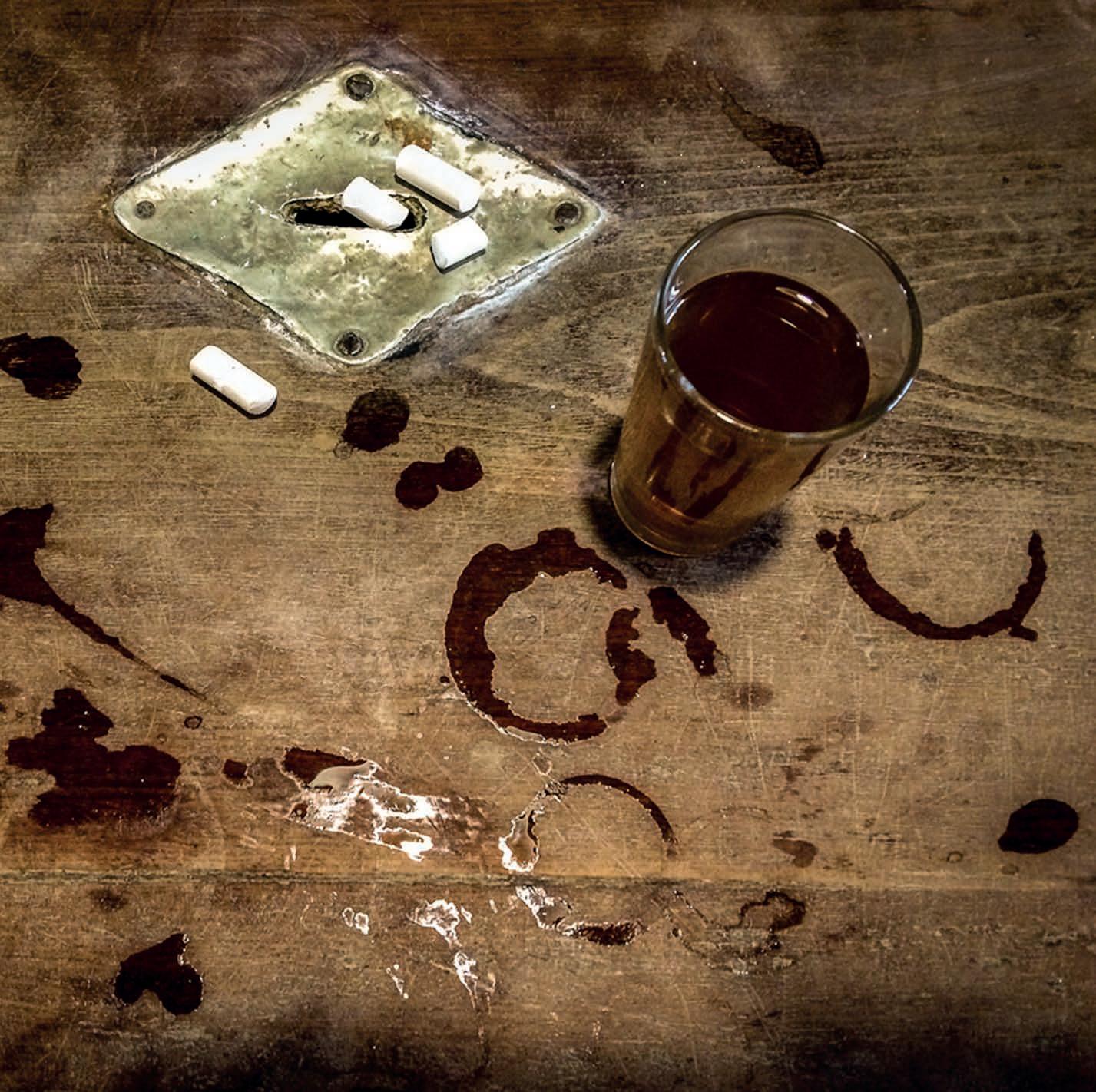

Amontillado from the barrel – or butt – with chalk at the ready for marking its quality thereon. Tabanco ‘El Pasaje’, Jerez de la Frontera.

The fne arches and high ceilings of Lustau’s bodega in Las Cruces. Its maturing sherry barrels are neatly stacked four criaderas high, in keeping with sherry tradition. Ruiz-Mateos’s financial dexterity was unprecedented in a world-class wine region. A toxic blend of misuse of government grants, unsecured loans and a general dismantling of once great sherry names that drove down quality, overshadowed everyone and everything. Only since around 2010 have sherry producers begun to recover, get their confidence back and make headway. Only in recent years have consumers begun to really appreciate the wonderful styles of wine that sherry has to offer. Only now are we beginning to reap the benefits of patience and the treasure trove that slumbers beneath sherry’s wondrous cathedral-like bodegas. A real sherry renaissance is underway. For many years I have been obsessed with the awful misfortunes of sherry. Having enjoyed its glories in the 1960s and worked in the sherry industry in the 1970s, as a natural watcher of wine trends I could not believe that such a respected and beloved wine had fallen on such hard times. This was highlighted when I sat next to a Master of Wine who said that she had never been to Jerez. This would have been unthinkable a generation ago. Jerez de la Frontera, in southern Spain, the home of sherry, used to be a magnet for all wine lovers. Enjoying a copita of fino or amontillado from the cask in a sherry bodega was akin to extolling the virtues of great En Primeur claret drawn from the barrel in a Bordeaux chai. And probably more fun. It was during my week at the annual Feria del Caballo, in Jerez, during May 2017, that I became overwhelmingly convinced that the wider world – all lovers of good wine – should be aware of the vinous treasures that Jerez has to offer. I was encouraged by friends of all ages, who urged me on to tell this beguiling story. Julian Jeffs’ classic book Sherry is without parallel. Recent books have, quite rightly, focused on tapas and cocktails. Sherry, Maligned, Misunderstood, Magnifcent! is more of a personal take on the current sherry scene. There have been so many recent ownership changes that I have now clarified ‘who owns who’ in Jerez. Many historic sherry brands have been consigned to the nostalgia heap. Many new boutique bodegas are now ruling the waves. The new pago or vineyard classification that is so vital to sherry’s future quality reputation has brought this wonderful wine right up to date. Above all, the focus here is on those innovative sherry companies that are bringing the different styles of sherry back to life. The bone dry manzanillas and finos, the elegantly nutty amontillados, palo cortados and olorosos, and the decadent Pedro Ximénez (PXs) – all of these styles form the bedrock of the sherry region.

The 1980s, 1990s and 2000s saw the consistent decline, year on year, of sherry sales. To lighten the tone against such a torrid background, I have explored how sherry has variously featured in popular culture, from Shakespeare to Mary Poppins, from Frankie Valli to Monty Python. As I write this in the cold winter months of 2019, I have a slightly jealous flashback to that feria in the heat of the Andalusian summer. My overriding sense then was that of fun, cautious optimism and dedication. Jerezanos are proud, charming people, with a sunny outlook. Nothing can illustrate this better than witnessing a Flamenco dancer enthralling her raucous but respectful and happy audience as they enjoy copita after copita of glorious chilled fino sherry in a private caseta. Placing her elegant hand firmly astride the hip, her haughty, puckered look expresses a foreboding sensuality. Then, with a click of the heels, a strut of the leg, and a thrust of the cascade of dark hair, she is off, her sensuously turning wrists evoking an abounding passion that ebbs and flows to the accelerating Flamenco beat. Outside, the sun was intense. A swathe of horse-drawn carriages processed around a hot sandy track; pretty long-haired girls in traditional Flamenco dresses gathered and fluttered in twos and threes. Elegant gentleman in bespoke suits joined in a myriad of conversations, twisting and turning, as their smiling faces convulsed into infectious laughter. The jeunesse dorée were out to play.

‘Jerezanos are proud, charming people, with a sunny outlook. Nothing illustrates this better than witnessing a Flamenco dancer enthralling her raucous but respectful audience...’

The Feria del Caballo in Jerez de la Frontera is the beating heart of sherry. It is here that the Jerezanos celebrate their unique wine, their fne horses and their mesmerizing dance. Over half a million half bottles of fno sherry will be consumed, and traditional Spanish dress is de rigueur. The Feria del Caballo in its home town of Jerez de la Frontera is the beating heart of sherry. Over half a million half bottles are consumed each year during this week-long feria. That is three million glasses of fino. By quirky contrast, one and a half million half-bottles are consumed each year during the annual feria in nearby Seville. That is nine million glasses. Although here the other great dry sherry style, manzanilla, is favoured. As the name of this feria implies, the horse is the absolute protagonist of this traditional annual event. This symbol of great breeding presides over the grounds of the González Hontoria Park during the magnificent parade of horses and horse-drawn carriages that dominates this extraordinary show. Sherry is a happy drink. Even happier now that this famous Andalusian wine has escaped from the narrow waisted, and narrow minded, ghastly (and

clumsy) Elgin schooner glasses of yesteryear. Sherry is beginning to feel truly liberated. She can now be swirled around a decent-sized wine glass, just like any other fine wine. Sherry can now flirt with the finest and dance with the best. I think granny and the vicar may be a touch bemused and bewildered by the swirling and dancing analogy, but there is no doubt about it, sherry is on the march again. To many, sherry is feminine in the summer, with those delicate and freshly chilled manzanillas and finos, and masculine in the winter, with its warming and lively amontillados and olorosos. Spring and autumn are times for the beguiling palo cortados. Christmas is the high spot for unctuous PX. And what about cream sherries? Well produced, wonderful and popular as they are, and will continue to be, they cannot reflect the true terroir and maturing solera system that create the soul of sherry. Cream sherries – rich or pale – are a particularly English invention. None the worse for that, but they answered a cold climate demand, rather than achieving the sensitive character of the unique location and climate of the Sherry Triangle in southern Spain. Sherry can only come from the vineyards of the Sherry Triangle. Bounded by Jerez de la Frontera to the north, Puerto de Santa Maria to the south and Sanlúcar de Barrameda to the west, these languid, undulating fields of vines are all close to the Atlantic Ocean. They also benefit from their proximity to the aridness of Africa and the gentleness of the Mediterranean Sea. Atlantic breezes entwine with the soft Levante winds which waft through the highceilinged bodegas. These majestic stone built edifices act as grand warehouses for the maturation of this unique wine. Precision ageing through the solera system has enabled sherry to achieve a near cult status in the pantheon of wine. A keen knowledge and appreciation of sherry was once indispensable for the wine connoisseur. He or she was as well versed in the nuances of fino and complexities of amontillado as they were in the terroirs of Bordeaux. For centuries, sherry was the recognized aperitif of all England. With the growth of cream and rich sherries, it could also be enjoyed after dinner. Every self-respecting Oxford don, each welcoming rural vicar, hundreds and thousands of dear old grannies, would open the conversation with the immortal words: ‘Would you like

A tiled map (and Tío Pepe advertisement) showing the vineyards of Jerez, and some of its most important pagos. These special vineyard sites – whose characteristics were all but lost in the bulk blends of the 1970s – are thankfully returning to the fore, and becoming a major feature of many of today’s sherries.

The Importance of Being Sherish

Map of Jerez by Francisco Zarzana in 1787, showing Jerez de la Frontera, Sanlúcar de Barrameda and Puerto de Santa Maria and their surrounding topography. Sherry, rather like Ernest in Oscar Wilde’s brilliant trivial comedy for serious people, The Importance of being Earnest, started off life with a different name. In the play, Jack Worthing adopts the alias Ernest when he wishes to visit London incognito. He falls in love with Gwendolen, who explains to him that she absolutely wants to marry someone called Ernest, because the name sounds so solidly aristocratic. Confused and crestfallen, Jack has many adventures in this delightful but preposterous play, before he eventually discovers, via the classic ‘handbag’ scene, that he was indeed christened Ernest, so his marriage to Gwendolen can go ahead. Sherry’s home is in Andalucía, in southwest Spain. The original dwelling place was known as Xera by the Phoenicians, Ceret by the Romans and Sherish or Seris by the Moors, who from 711 dominated Spain for 500 years. When the Christians conquered the town in 1264, they christened it Xeres. Xeres gradually transformed into the name Jerez, which officially became Jerez de la Frontera in 1380. Jerez is pronounced ‘hereth’, with a guttural ‘h’ in Andalusian Spanish. This was a bit difficult for the English to say with any confidence. So Jerez became ‘sherry’. The Spaniards thus produce a world class wine, whose international name was essentially created by the English. Maybe it should revert to Sherish? Or would that suggest one had already had several glasses of this fine stuff? In comparison, I cannot imagine the French being so accommodating. Although it’s perhaps of note that the names for their ‘claret’ in the UK and ‘burgundy’ internationally are recognizably English.