11 minute read

Pier Paolo Pasolini. Everything is Sacred. The Political Body

Bartolomeo Pietromarchi Director, MAXXI Arte

Pier Paolo Pasolini. Tutto è santo (Everything is Sacred ) is an exhibition of broad scope that explores the multiple aspects of Pasolini’s work and biography: the leitmotif here is the body, a constant presence in his practice. The exhibition unfolds across three events in three different locations in Rome: the Palazzo delle Esposizioni and the Gallerie d’arte antica Barberini Corsini, which focus on, respectively, the poetical body and the prophetic body , while at MAXXI we have chosen to consider the political body and to explore it in a unique way, that is, by concentrating on a single year—1975—the final year of his life. In fact, Pasolini died tragically in the early hours of November 2 and left behind a series of unfinished works, including his most ambitious and most significant novel, Petrolio , published posthumously along with other testimonies from his final period.

The year 1975 was one of Pasolini’s most active: conferences, interviews, newspaper articles, TV appearances. With his customary polemical and provocative accusations, he admonished, responded, and raised the stakes. His interventions touched upon controversial and relevant issues like abortion, homosexuality, the abuse of power, and the destruction of Italian tradition and identity as perpetrated by the unchecked affirmation of mass culture. His voice has always been recognizable—dead set against trends, confrontational, immune to the ideological allusions and self-interests that resounded during the years of the “strategy of tension,” of trade union strikes, of mass youth movements, and of battles for civil rights, as Marco Belpoliti admirably retraces in this catalogue.

The exhibition at MAXXI offers a philological reconstruction of Pasolini’s final period, analyzed with the help of an important selection of visual materials and documents, as well as expansive observations on Pasolini’s notoriety following his death, in particular during these past three decades, when his multifaceted practice has gradually become a source of inspiration, building material, and a reservoir of themes and allegories for the latest generations of artists.

This essay aims to analyze the bond between Pier Paolo Pasolini and Fabio Mauri, the poet’s friend and companion since his early days in Bologna, when both, a little over twenty years old, worked on the editorial staff for the magazine Il Setaccio. 1 A close fellowship was immediately forged between them, both in terms of cultural sensitivity as well as a true artistic vocation, with particular attention to the body and its two-fold aesthetic and political aspects.

Fabio Mauri thus became a forerunner of the dialogue “at a distance” between Pasolini and the art world, an echo destined to last over time and which continues even today, in the interventions of the contemporary artists exhibited at MAXXI.

Pier Paolo Pasolini. Tutto è santo.

Il corpo politico

Bartolomeo Pietromarchi Direttore MAXXI Arte

Pier Paolo Pasolini. Tutto è santo è un ampio progetto espositivo che indaga i molteplici aspetti dell’opera e della biografia dell’autore seguendo come filo conduttore il corpo, presenza costante nella sua creazione. La mostra si articola in tre tappe e in tre luoghi diversi della città di Roma: il Palazzo delle Esposizioni e le Gallerie d’arte antica Barberini Corsini, che si concentrano rispettivamente sul corpo poetico e sul corpo veggente , e il MAXXI, dove abbiamo scelto di prendere in considerazione il corpo politico e di farlo in una chiave insolita. La mostra quindi si concentra su un unico anno, il 1975, l’ultimo di vita di Pasolini che, infatti, muore tragicamente nella notte tra il primo e il 2 novembre lasciando una serie di opere incompiute, tra cui il suo romanzo più ampio e significativo, Petrolio , pubblicato postumo insieme ad altre testimonianze del suo periodo finale.

Il 1975 è uno degli anni in cui Pasolini è più attivo: conferenze, interviste, articoli sui giornali, presenze televisive: con la sua abituale carica polemica e provocatoria accusa, avverte, risponde, rilancia. I suoi interventi toccano temi scottanti e attuali come l’aborto, l’omosessualità, gli abusi del potere, la distruzione della tradizione e dell’identità italiana effetto dell’affermazione incontrastata della cultura di massa. La sua voce è sempre riconoscibile, strenuamente controcorrente, provocatoria, insensibile ai richiami e alle convenienze ideologiche che risuonano negli anni della “strategia della tensione”, delle lotte sindacali, dei movimenti giovanili di massa, delle battaglie per i diritti civili, come ha ben ricostruito in questo stesso catalogo Marco Belpoliti.

La mostra del MAXXI offre una ricostruzione filologica dell’ultimo periodo di attività di Pasolini, analizzata con l’ausilio di un’importante selezione di materiali visivi e di documentazione, e al tempo stesso estende il suo raggio di osservazione alla fortuna postuma dell’autore e, in particolare, agli ultimi tre decenni, quando la sua opera multiforme è diventata, di volta in volta, fonte di ispirazione, materiale di costruzione, riferimento tematico e allegorico per gli artisti delle generazioni più recenti.

Questo saggio si propone di indagare il legame tra Pier Paolo Pasolini e Fabio Mauri, amico e sodale dell’autore sin dagli anni bolognesi, quando entrambi, poco più che ventenni, collaboravano alla redazione della rivista “Il Setaccio”1. Tra i due nacque sin da subito un rapporto molto stretto, sia in termini di sensibilità culturale sia di impostazione artistica vera e propria, con particolare riguardo alla tematica del corpo e alla sua doppia valenza estetica e politica. Fabio Mauri si fece così precursore di un dialogo “a distanza” tra Pasolini e il mondo dell’arte, un’eco destinata a durare negli anni e che si protrae fino a oggi, negli interventi degli artisti contemporanei esposti al MAXXI.

On May 31, 1975, in Bologna, at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Mauri screened Il Vangelo secondo Matteo (The Gospel According to St. Matthew) upon Pasolini’s chest. Immobile, seated in front of the audience wearing a white shirt, with his face in dim light, the filmmaker agreed to subject himself to a sort of cathartic ritual of public display: screening a film upon its creator. Blinded by the projector’s light, and with an intentionally loud soundtrack, he endured, as Mauri himself would later state, an “X-ray of the soul” of subjectivity and of conscience, in a series of interchanging roles between author and spectator. As Stefano Chiodi wrote concerning this action: “The performance Intellettuale is therefore a hermeneutic display of Pasolini’s work, transposed onto a unique conversational level, in which the linguistic dissection of the mechanism of representation is implemented in parallel with a presentation of the ‘ecstatic’ and performative nature of his body.”2

Almost two months earlier, on April 8, Mauri had held in Rome another version of this same performance as part of a much broader project—a set of actions and installations with a title laden with memories and political insinuations, Oscuramento, intended to be a journey in three stages, three “stations” one could say, that the audience was invited to visit. At the heart of the work were references to the artistic and civil universe shared by Mauri and Pasolini, starting from the single discerning awareness of a political and cultural threshold that Italy at the time was forced to cross. The backdrop was historical, as confirmed by the three venues selected by Mauri for his interventions (the Studio d’arte Cannaviello, the Museo delle Cere [Wax Museum] in Piazza Santi Apostoli, and Elisabetta Catalano’s photography studio), all very close to Piazza Venezia, a key location for Fascism.

It was precisely Oscuramento, unquestionably one of Mauri’s most complex works, that became for MAXXI the theme for a critical and documentary reconstruction whose constant reference is the figure of Pasolini, who during those months was finishing the editing for Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma (Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom). For his final film, Pasolini combined Sade’s novel with the grim and violent setting of Italy during the years of civil war and of the Resistance, thus turning this story into a metaphor for a human condition observed in its most revolting and contradictory aspects.

In Oscuramento, Mauri treated similar themes: the abuse of power, the constant recourse to depravation and humiliation of the weakest, the cult of violence and death. Both artists reflected not only on the twentieth century’s darkest legacy, but also on its sudden comeback in opulent societies, in the dark heart of consumer economies and cultures. Those were the years when intellectuals were invited to keep a watchful eye on the resurgence of hidden forms of totalitarianism and the risk of a new, and even more pervasive, “black out.”

Both artists shared, in an essential and unified intuition, the centrality of the body and its biopolitical value. This was a theme, crucial to the game of negotiating the identity of modern man from the Shoah onward, that proved pivotal for cultural reflections from the 1970s to today. It all began at a prearranged time on April 8, in the Cannaviello gallery, where the first action took place with its protagonist, the Hungarian director Miklós Jancsó, whose chest was used to screen his film Salmo rosso (Red Psalm, 1971). This was Mauri’s first screening upon bodies and objects, a method he would use various times over the years. The body is the place that and consolidation, in this case in the contexts we usually call Western. If Pasolini, therefore, advanced—with the power of poetry and of scandal—homosexuality and gender issues, at the origin of biological life, denouncing “anthropological mutation,” abuse of power, violence, marginalization, and racism, Mauri, in turn, explored the seductive mechanisms of totalitarian ideology, including its forms and its ability to manipulate the way we perceive ourselves and others. Both paved the way for a long process of deconstructing subjectivity and its political negotiations, amplified today by the virtual dimension of social media, which offers an incessant reinvention and multiplication of identity and gender in a process that is fluid and in constant motion, eluding established categories and definitions. A lengthy gestation, especially as regards gender studies and reflections that have attracted our attention on the need for a diverse, more aware, and freer inclusivity.

1 The magazine Il Setaccio was published in Bologna between late 1942 and May 1943. The first issue of the magazine came with a drawing by Pasolini on the cover.

2 Stefano Chiodi, “Dalla voce alla presenza. Il corpo del poeta nel tempo dello spettacolo”, in La rivista di Engramma no. 181, May 2021, 381.

3 Fabio Mauri, Intellettuale 1985, in Pier Paolo Pasolini. Una vita futura. La forma dello sguardo, exhibition catalog (Rome, Mercati di Traiano, October 15–December 15, 1985).

© Eredi Fabio Mauri Courtesy the Estate of Fabio Mauri and Hauser & Wirth Foto | Photo Enzo Cannaviello e dunque nei processi di costruzione e rielaborazione delle identità. Pasolini e Mauri avevano intuito come la negoziazione delle identità personali che passano per la ridefinizione del corpo e di ciò che è accettato o rifiutato, sarebbero divenute il fulcro delle future battaglie per la conquista dei diritti civili, la cui posta è l’affrancamento dell’uomo dai poteri autoritari, normativi, e il cui effetto è un’autoaffermazione del sé in ogni sua forma. Ciò che entrambi ponevano al centro della loro riflessione era il concetto di “anomalia corporea”, intesa nel suo senso più ampio, che include sia il sesso biologico, sia la presentazione del sé in una modalità discordante dai codici prestabiliti – dunque anche quelli sessuali (genere e orientamento sessuale) e sentimentali – che supera qualsiasi concetto di “devianza” e, per estensione, di peccato, crimine, malattia.

La nozione di devianza si è in effetti sviluppata attorno all’idea di una discordanza, di un allontanamento da ciò che rispetto al corpo (e agli atti corporei) si è imparato a riconoscere come “naturale”, ossia normale, legittimo, lecito e sano. La discordanza riguarda il modo diverso di guardare se stessi, ma anche all’altro da sé, rispetto a un ordine costituito, a una norma codificata. Sono queste dissonanze che consentono una riflessione su come l’idea di “giusto” rispetto alle soggettività – nonché l’idea di ordine e relativa devianza da questa idea – non sia “naturale” ma la risultante di processi storici, culturali e sociali che ne hanno prodotto la configurazione e il consolidamento, in questo caso nei contesti che si usa definire occidentali.

Se Pasolini ha dunque posto con forza poetica e di scandalo la questione omossessuale e quella relativa ai generi, all’origine della vita biologica, denunciando la “mutazione antropologica”, la prevaricazione e la violenza, l’emarginazione e il razzismo, Mauri si è interrogato a sua volta sui meccanismi seduttivi dell’ideologia totalitaria, sulle sue forme, sulla sua capacità di manipolazione della percezione di sé e degli altri. Entrambi hanno gettato le basi per un lungo processo di decostruzione della soggettività e della sua negoziazione politica, amplificata oggi dalla dimensione virtuale dei social media, nei quali si assiste all’incessante reinvenzione e moltiplicazione di identità e generi in un processo fluido e in continuo movimento che elude categorie fisse e definizioni.

Una lunga gestazione soprattutto negli studi e nelle riflessioni di genere che hanno attirato la nostra attenzione nei confronti della necessità di una diversa, più consapevole e libera inclusività.

1 La rivista “Il Setaccio” fu pubblicata a Bologna tra la fine del 1942 e il maggio del 1943. Il primo numero è corredato da un disegno di Pasolini in copertina.

2 Stefano Chiodi, Dalla voce alla presenza. Il corpo del poeta nel tempo dello spettacolo, in “La rivista di Engramma” n. 181, maggio 2021, p. 381.

3 Fabio Mauri, Intellettuale 1985, in Pier Paolo Pasolini. Una vita futura. La forma dello sguardo, catalogo della mostra (Roma, Mercati di Traiano, 15 ottobre–15 dicembre 1985), Roma 1985.

Noor Abed

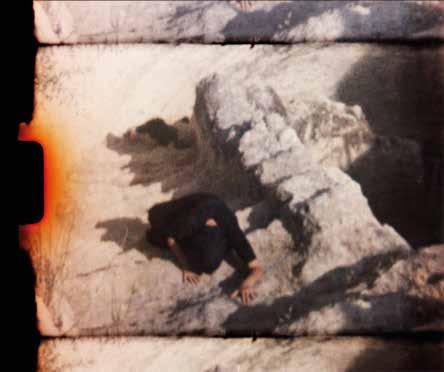

Jerusalem, 1988 our songs were ready for all wars to come, 2021 Film in pellicola Super 8 | Super 8 mm film, 22’

6 disegni A5 | A5 drawings

Courtesy l’artista | the artist

Noor Abed is a filmmaker, multidisciplinary artist, and performer working at the intersection of performance and film. Her practice examines notions of choreography and speculative relationships between individuals, creating situations where social possibilities are both rehearsed and performed. For the artist, mythology, folklore, and the collective imagination are tools for analyzing and questioning history and trying to envision different realities, plural and alternative narratives, and forms of daily resistance.

The work our songs were ready for all wars to come is composed of choreographed and musical scenes, based on documentation of traditional Palestinian stories. With this work the artist strives to create a new aesthetic to evoke stories from oral traditions that describe—while also focusing on song and voice—the symbolic bond between wells and the community rituals of death and disappearance. our songs were ready for all wars to come explores the transformative potential of folklore as a source of collective knowledge and alternative social and representational models in Palestine. Popular songs—in the outlook of the archaic world imagined by the artist—become a shared tool in everyday resistance and emancipation on the part of communities and lands oppressed by neoliberal and colonial hegemonies. They also offer a way to overturn dominating discourses, to reflect on history, and to imagine an alternative reality free from oppression.

Noor Abed è una film-maker, artista multidisciplinare e performer che lavora all’intersezione tra performance e film. La sua pratica artistica esamina infatti la coreografia e la performance, indagando i meccanismi e le condizioni di produzione della conoscenza in vari contesti sociopolitici. La mitologia, il folclore e l’immaginazione collettiva diventano per l’artista gli strumenti per analizzare e interrogare la storia e provare a immaginare realtà differenti, narrazioni plurali e alternative, forme di resistenza quotidiana.

Il lavoro our songs were ready for all wars to come si compone di scene coreografate e musicate, basate sulla documentazione di racconti popolari palestinesi. Con quest’opera l’artista vuole creare una nuova forma estetica per evocare storie della tradizione orale che raccontano – mettendo al centro il canto e le voci – il legame simbolico tra i pozzi d’acqua e i rituali comunitari della morte e della scomparsa. our songs were ready for all wars to come esplora il potenziale trasformativo del folclore in quanto fonte di conoscenza collettiva e la sua possibile connessione con modelli sociali e rappresentativi alternativi in Palestina. I canti popolari nella visione del mondo arcaico immaginato dall’artista diventano uno strumento comune di resistenza quotidiana e di emancipazione da parte di comunità e terre oppresse da egemonie neoliberali e coloniali, un modo per sovvertire i discorsi dominanti, riflettere sulla storia e immaginare una realtà alternativa e libera dalle oppressioni.