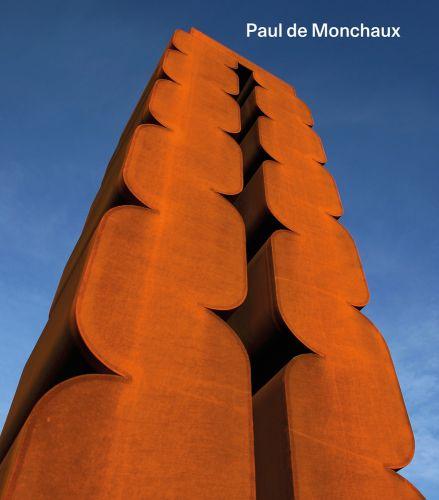

There is a new work on display in Paul de Monchaux’s garden studio. Volute VI (2018) occupies the centre of the space, like a new kid in the class. Plaster white, ready to be cast in bronze, it sits atop its plinth with swanlike mock-bashful confidence. Tilly, the family dog, gives a sage nod of approval, while the surrounding sculptures are mute, as if awaiting a reshuffle. Volute VI is the latest in a series of works taking as their starting point the decorative scrolls found at the top of Ionic columns in classical architecture. To make the work, De Monchaux has taken a section derived from the construction of a root-two rectangle on a complex journey through space. A graceful, insistent circuit is forged, with determined avenues followed by gentle detours and swift double backs. From a particular angle, the symmetry of the piece clicks into place enabling a sudden stasis, a momentary resolution, before it again assumes its sinuous progression through asymmetry, like ‘a swimmer in space’.1

Volute VI is an assured summation of eight decades of artistic endeavour: a career in which Paul de Monchaux has applied the objective rigours of geometry and measurement to forge sensuous, ambiguous forms in time and space. In many ways, the circuitous flourishing of Volute VI parallels the shape of De Monchaux’s development as an artist: a nub of journeys and ideas enriching one another across time. His course has bowed to accommodate the convergence of teaching and family commitments, before emerging in a late flowering of creativity during so-called ‘retirement’. In establishing an overview of this significant yet underacknowledged practice, an underlying interest in notions of passage and juncture surfaces: one driven by a desire to traverse boundaries in search of fresh points of connection.

Standing in the studio, looking across at recent work, De Monchaux returns with ease to the vivid intensity of early memories. Born in Montreal in 1934 to entrepreneurial parents, he recalls an itinerant childhood, attending 15 schools across Ireland, Australia, Canada, the USA and South America. De Monchaux embraced each upheaval, drawing particular inspiration from the physical experience of travelling on huge passenger ships. He describes with awe the slow movement of a massive liner, ‘a wall of shaped steel’, tugged into dock. He recalls his tiny frame leaving solid

ground to enter the narrow gangway and move up into the huge vessel; and the freedom to roam the ship for weeks on end, senses heightened by shifts in perspective, scale and climate. Equally close to the surface is the material memory of an impressive feature in the landscape close to one temporary home in Fairfax, Virginia, near Washington DC. This vertical cut exposed a seam of clay that De Monchaux worked with his hands. He produced the shapes that his brother, later an architect, would develop into infrastructure: a miniature civilisation of sorts.

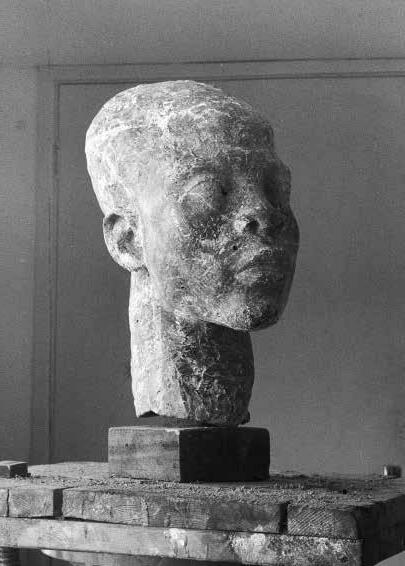

On leaving school aged 17, De Monchaux moved to New York City in 1952. He worked as an assistant in a fashion photography retouching studio and attended sculpture classes at the Art Students League during the evenings. It was an informal studentship, which he supplemented with frequent trips to the Museum of Modern Art, where he encountered the work of Constantin Brancusi for the first time. Yearning for greater discipline, and aware of the significance of European (and particularly British) developments in modern sculpture, he travelled to London in 1955 to accept a place at the Slade School of Art. Here, teaching encouraged the strict scrutiny of the figure under the watchful eye of Professor Alfred Gerrard, with regular crits from visiting artists including Reg Butler, F. E. McWilliam and, more occasionally, Henry Moore. Measurement and proportionality were paramount. Working directly from the life model, the students plotted observations in clay onto precise metal armatures: a flowering of figuration from a geometric core. This analytic and structured process was of fundamental importance to De Monchaux, and the subtle gradations between abstraction and figuration, internal and external form, have fed his practice ever since.

Alongside his studies, De Monchaux continued to extend his terms of reference. During the holidays he was employed at a quarry in Dorset where he produced handmade kerbstones for local footpaths, gratefully accepting offcuts for his own work. Frequent trips to galleries and museums enhanced a growing awareness of his role as a tiny cog in a relentless global progression of creativity. He marvelled at archaic Greek and early Egyptian sculpture in the British Museum, the Auguste Rodin works from the Victoria & Albert Museum on loan to the Tate Gallery, and early Renaissance architecture on a trip to Florence, discerning across time and discipline ‘a common enterprise’.2 On graduation in 1958, De Monchaux accepted a teaching position at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology in Zaria, Nigeria, where he lived for two years with his wife, the fellow artist Ruth Blackett, and their infant son, Stephen.3 Although the students were keen to learn about Western developments, he organised guided field trips to Jos, Osogbo, Issie, Tada, Benin and Ife, finding exceptional examples of indigenous art to inspire his students. By proxy, this experience extended and enriched his own understanding of sculpture.

Examples of De Monchaux’s early work can be found around his home.

A small reclining River God (1961) writhes on a table with an athletic arch. A clutch of exquisite, perfectly proportioned bronze hands (1962–63) reaches upwards, almost votive, from a workbench. A portrait of his mother, Ellen (1965), peers down from a shelf; one of a pair, ‘she was all face; Dad was all head’. There is shared movement and spontaneity, reinforced through the agile actions of the artist’s hands, pummelling wet clay and plaster into shape. Despite this liberated quality, forms remain independent: either a static head or a restless hand, an upright bust or a reclining motif.4 Gradually, a greater sense of connectivity and conceptual complexity emerged. The catalyst for change appears to have stemmed from De Monchaux’s tender observation of Ruth’s intuitive choice of pose for reflection: her face resting on her hand, her palm and fingers providing the meeting place of thought and action.

At first glance, Head and Hand I (1969) seems abstract. From a specific vantage point, however, Ruth’s pose rushes into view. De Monchaux built the work in clay sections without an armature, the final form only materialising after bronze casting. This ‘blind’ and additive process, coupled with the spontaneous handling, suggests an ongoing fascination

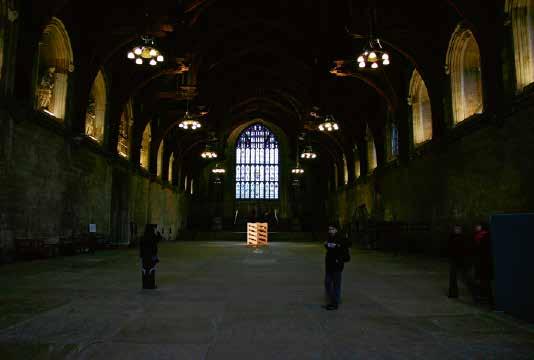

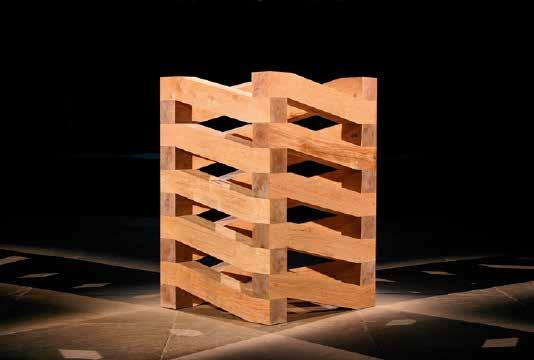

Song 2005

106

Green oak, 2.1 × 1.4 × 1.4 m

BBC Memorial to Winston Churchill, Westminster Hall installation, London

Green oak, 2.1 × 1.4 × 1.4 m

BBC Memorial to Winston Churchill, Westminster Hall installation, London

Published in 2019 by Ridinghouse

Ridinghouse

46 Lexington Street

London W1F 0LP

United Kingdom ridinghouse.co.uk

Distributed in the UK and Europe by Cornerhouse Publications

c/o Home

2 Tony Wilson Place

Manchester M15 4FN United Kingdom cornerhousepublications.org

Distributed in the United States and Canada by ARTBOOK | D.A.P.

75 Broad Street, Suite 630 New York, New York 10004 artbook.com

Acknowledgements:

My thanks: To my wife Ruth and three generations of my extended family for their constant help and encouragement.

To my very good friends Tess Jaray and Megan Piper for their unstinting enthusiasm and support for the work. And to Claudia Tobin and Lily Le Brun for their penetrating past exhibition texts.

To Vivien Lovell for her help over many years on public projects. And to Alison and Derry Irvine for their generous and timely patronage.

To Karsten Schubert, Sophie Kullmann, Mark Thomson, Jane Davies and Peter White, for their excellent work on all aspects of the book. And to Natalie Rudd and Jon Wood for enriching my own understanding of the work during our collaboration on this publication.

Paul de MonchauxAll photography by Paul de Monchaux unless otherwise stated below:

© Emma Brooker: pp.144 and 146 top

© Rod Dorling: p.101

© Tess Jaray: p.8 top

© Reuben Kench: p.155

© Liz Kessler: pp.12–13

© Estate of Wilfred Owen and Courtesy of Chatto and Windus: p.149 bottom

© Christopher Sturman: pp.1, 20, 156, 159

© Succession Brancusi – All rights reserved. ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018: p.147

© Peter White: pp.6, 18, 39, 43, 47–48, 52–53, 55, 72–75, 80–81, 86–87, 89, 94–99, 108–109, 112–113, 115–119, 122–123, 128–131, 134–143, 149 top

Images © Paul de Monchaux

Texts © Natalie Rudd, Jon Wood and Paul de Monchaux

For the book in this form © Ridinghouse

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any other information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-inPublication Data

A full catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 909932 49 4

Edited by Sophie Kullmann

Designed by Mark Thomson Set in Unica77

Printed in Belgium by die Keure