5 minute read

Kabanova, Narisuem – budem zhit’, p.50

Viacheslav Mizin, Insectoid, 1989; Atrium-Columbary by Viktor Smyshliaev and Viacheslav Mizin, 1985. Aurora, an administrative building by Andrei Kuznetsov, 1989) Yet, apart from an endless play with geometric forms and volumes, these disembodied, decontextualized, grim and gloomy post-utopian landscapes promised (and delivered) nothing – whether narratively or pictorially. And perhaps, it was not by accident that at the turn of the decade Novosibirsk architect found themselves busy with an exhaustive production of visual representations of various “administrative bastions” – massive, unassailable, self-imposing and self-sucient structures that needed nobody. (Ill. 18-19. Façade of the village Council by A. Chernov and S. Grebennikov, 1990; Self-sucient administrative and managerial bastion by XXXX. 1989) Various attempts at self-inscription and embeddedness, various practices of tactful vkluchenie and vkhozhdenie, the cultivation of the chronotopic aect with its distinctive feeling for the place ended rather grimly – with deadening technoscapes and anti-utopian fantasies of claustrophobic towers and enclosures. Was it worth the trip?

In one of his essays, Viktor Shklovsky, the founder of Russian Formalism, made an observation that is just as striking as it is banal: “Homes that have not been built cannot fall down” (nepostroennye domiki ne padaiut).20 A failure requires an actual eort, actually built walls, the critic seems to suggest. Apparently, his observation does not work in reverse. As the history of WMoscow paperists shows, success is indeed possible without building actual houses; paper architecture might work just fine. There is a third way, too. Structures envisioned by Siberian paper architects were never built and they never fell. But they did not generate much success, either.

As parts of the Siberian paperists’ archive become more and more accessible now, the question hinted at by Shklovsky sounds more and more relevant: What do we do with the houses that have never been built? Why should we care about dreamscapes that resulted in nothing? Why bother? Why now?

As I tried to show, there is no easy answer to these questions. The phenomenon of paper architecture points to a series of crucial questions – about the impact of fading utopia; about the importance of aect; about the necessity to be rooted – somehow, somewhere. Perhaps, most importantly, it draws attention to the issue observed many years ago by Yakov Chernikhov. We need these fantasies about houses that would never be built, the architect maintained, because they give us tools for working through problems that could not be addressed, named, or envisioned otherwise. Fantasies provide us with means to deal with issues that have remained unapparent, ungraspable, and, therefore, unnoticed. Fantasies are good for anticipating things that might come in the future. After all, dreamhouses do not fall. But real houses do. III.19

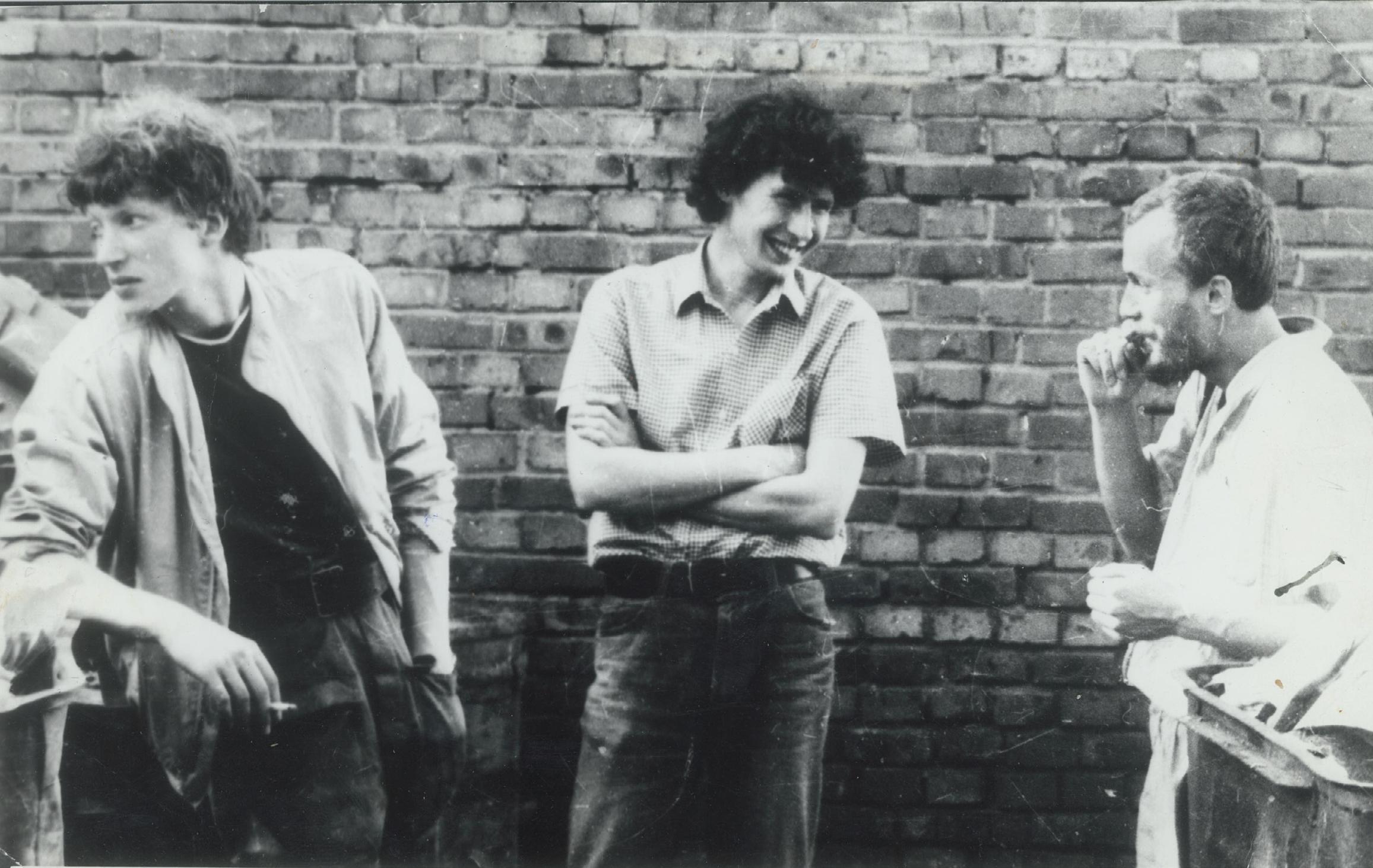

Viktor Smyshlyaev, at the roof of The Institute of Civil Architecture, 1985

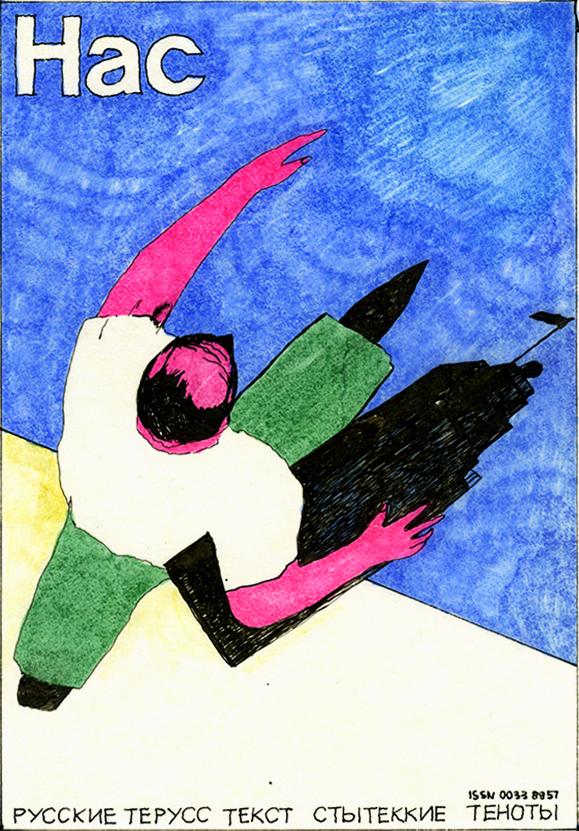

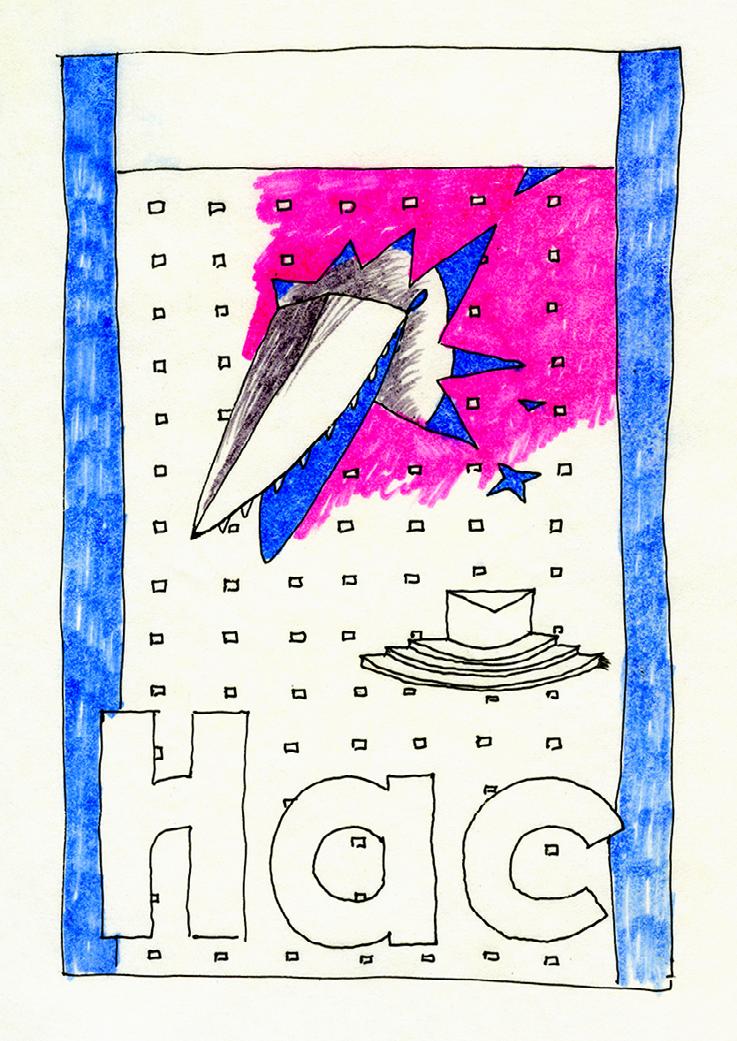

NAS POSTER 1985 Viktor Smyshlyaev

NAS

This poster started the NAS group.

bottom right NAS POSTER 1985 Viktor Smyshlyaev

Andrey Kuznezov, Slava Mizin, Viktor Smyshlyaev, 1985

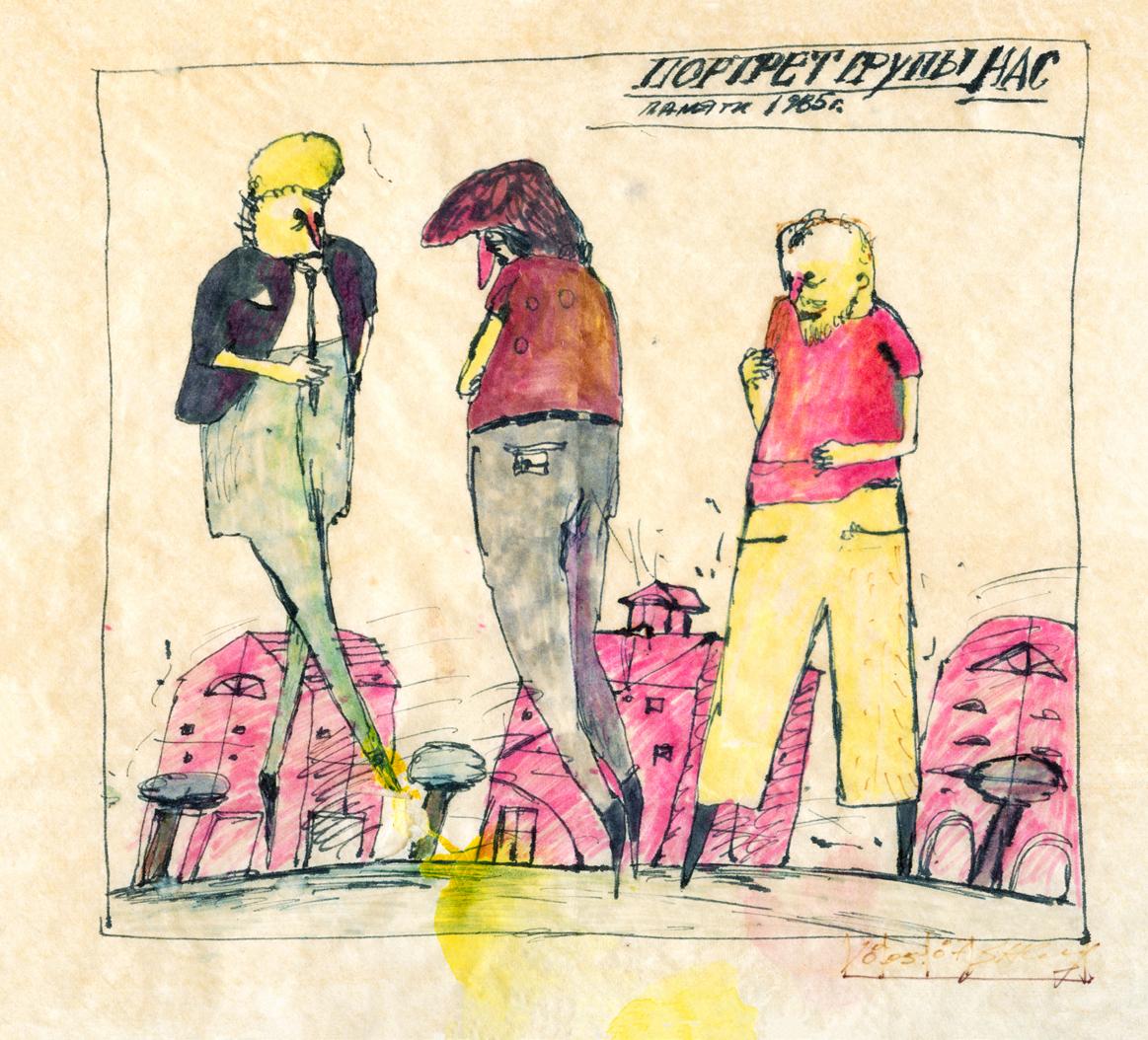

PORTRAIT OF THE NAS GROUP: Andrey Kuznezov, Slava Mizin, Viktor Smyshlyaev 1985 Viktor Smyshlyaev

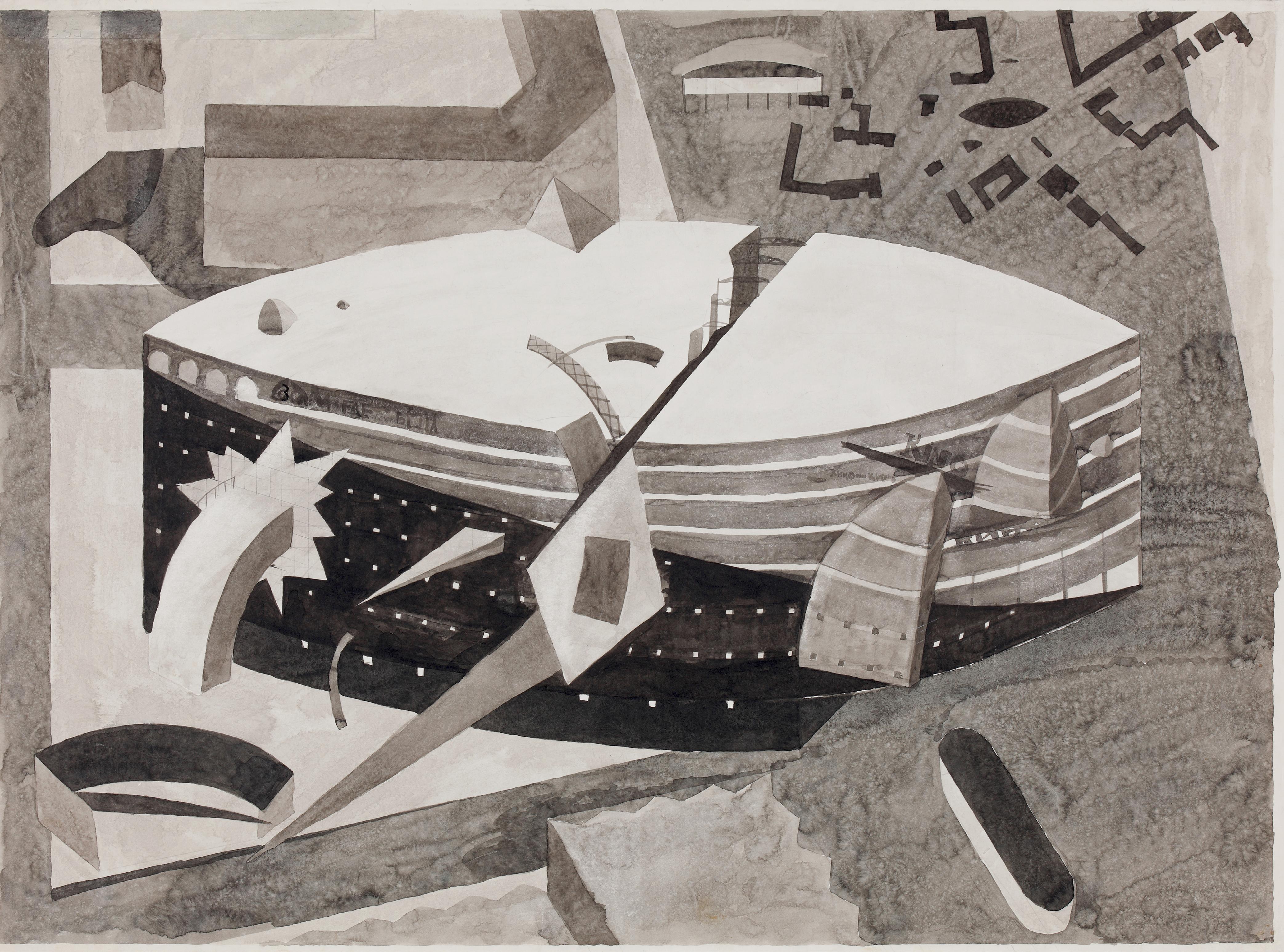

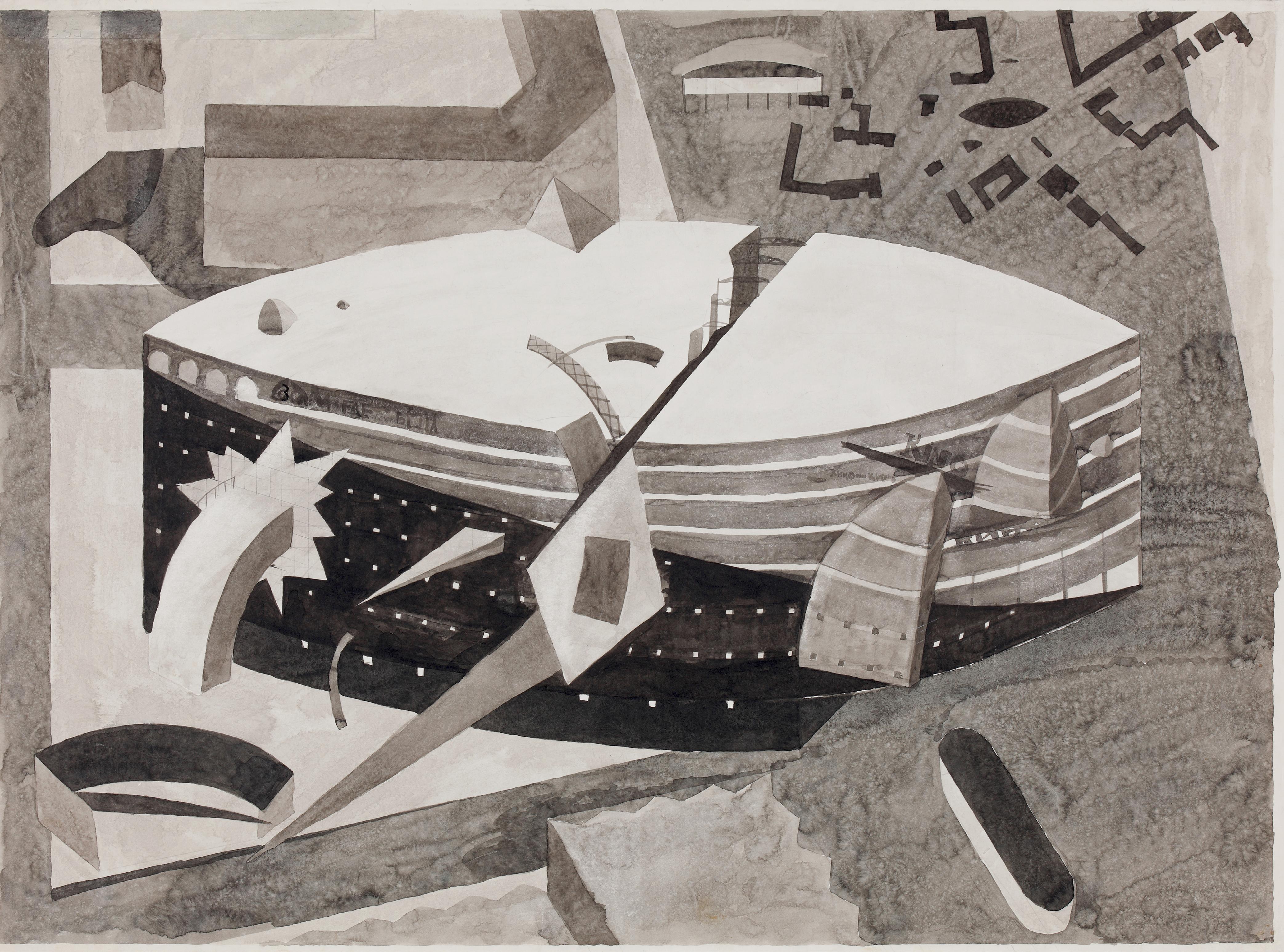

The project of the Perspective Cinema, also known as the “Lens’ or “Iron”, is a benchmark for the generation of ‘paper architecture’ in Novosibirsk. The above text was inserted by Viktor Smyshlyaev into one of the graphic sheets of the architectural presentation of the project.

The text is evidence of the crisis of modernism; it declares professional self-destruction, signifies the outcome of architectural thinking from the material into sensations, ‘film-like’, which may be considered the characteristic features summarizing the experience of Siberian paper architecture.

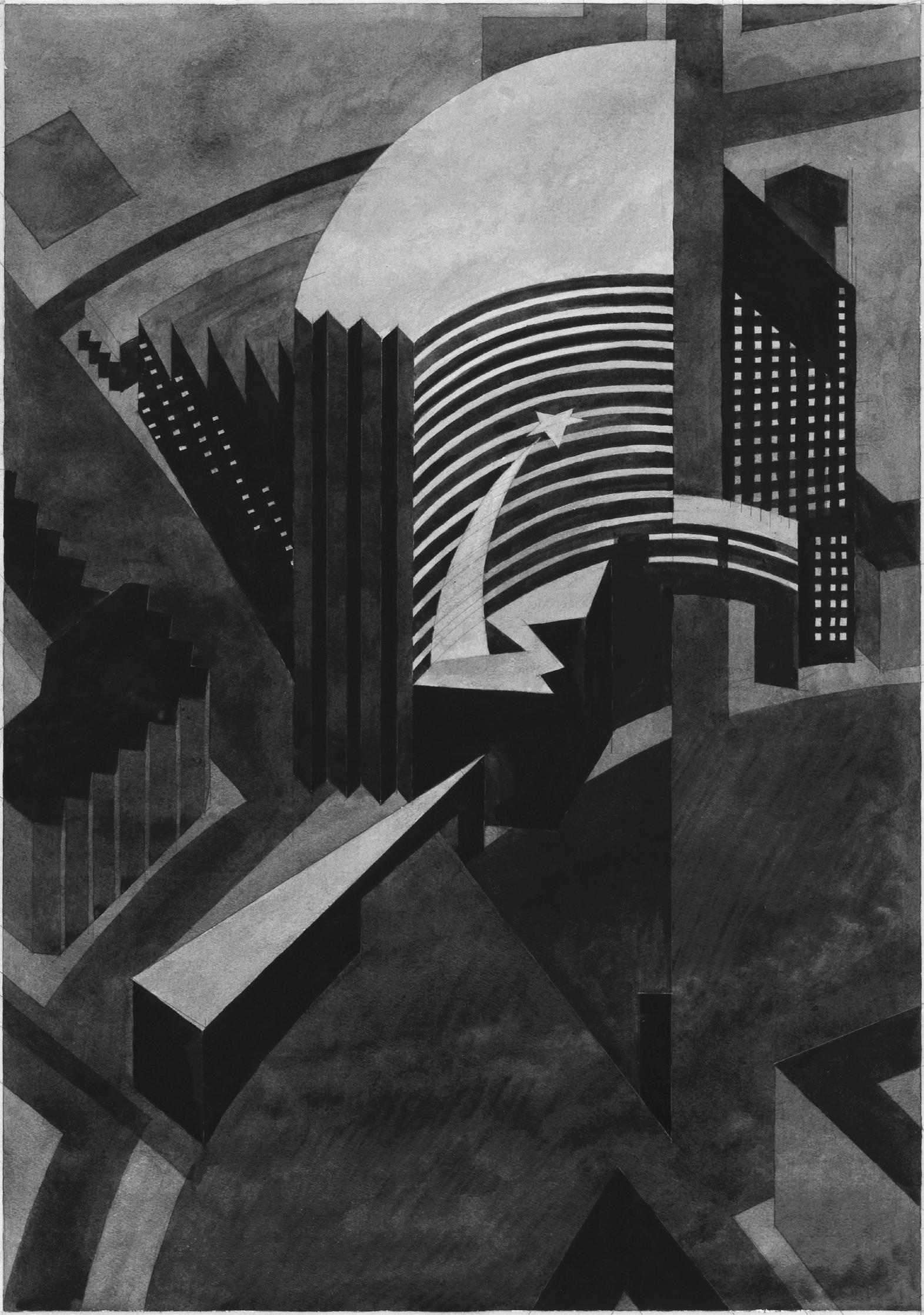

PERSPECTIVE CINEMA 1985-1986 Viktor Smyshlyaev Yevgeny Burov

Multiple ways to create illusory worlds are a reason to break the cinema’s vast lens with numerous peculiar objects of radical architectonics, and the hectic graphic points out, that the building is made out of someone’s dreams or something similar just like any cinema is made.

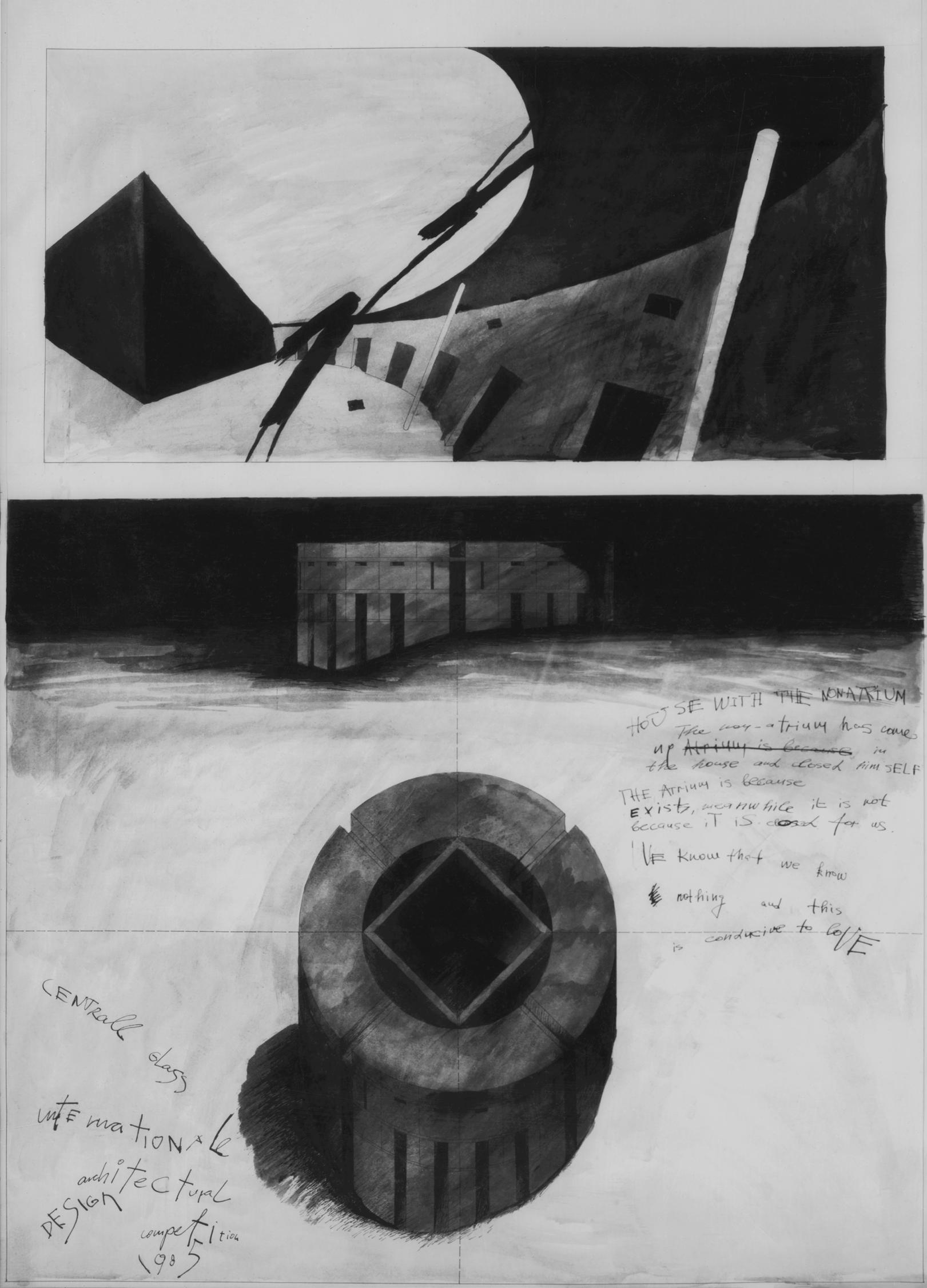

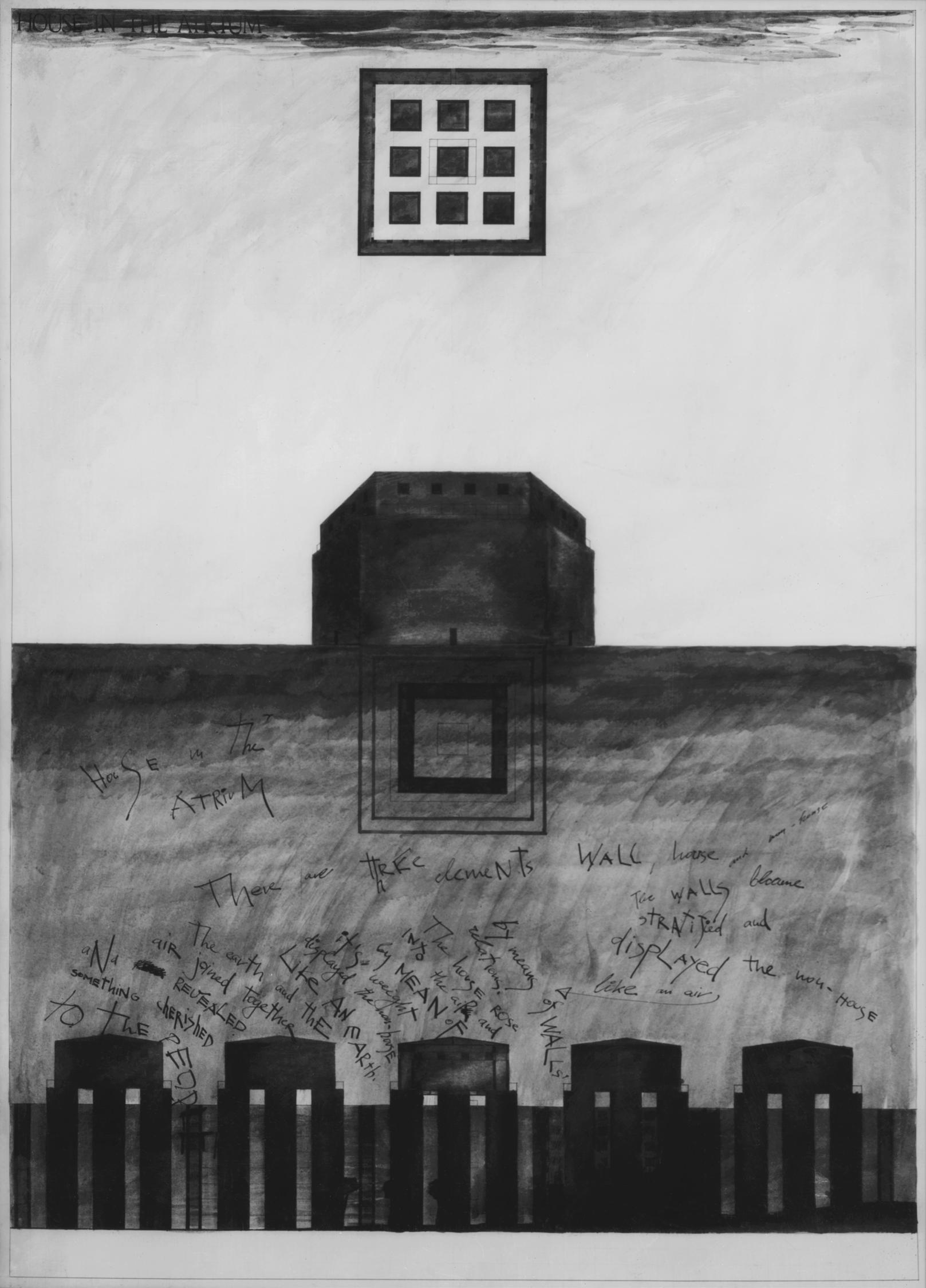

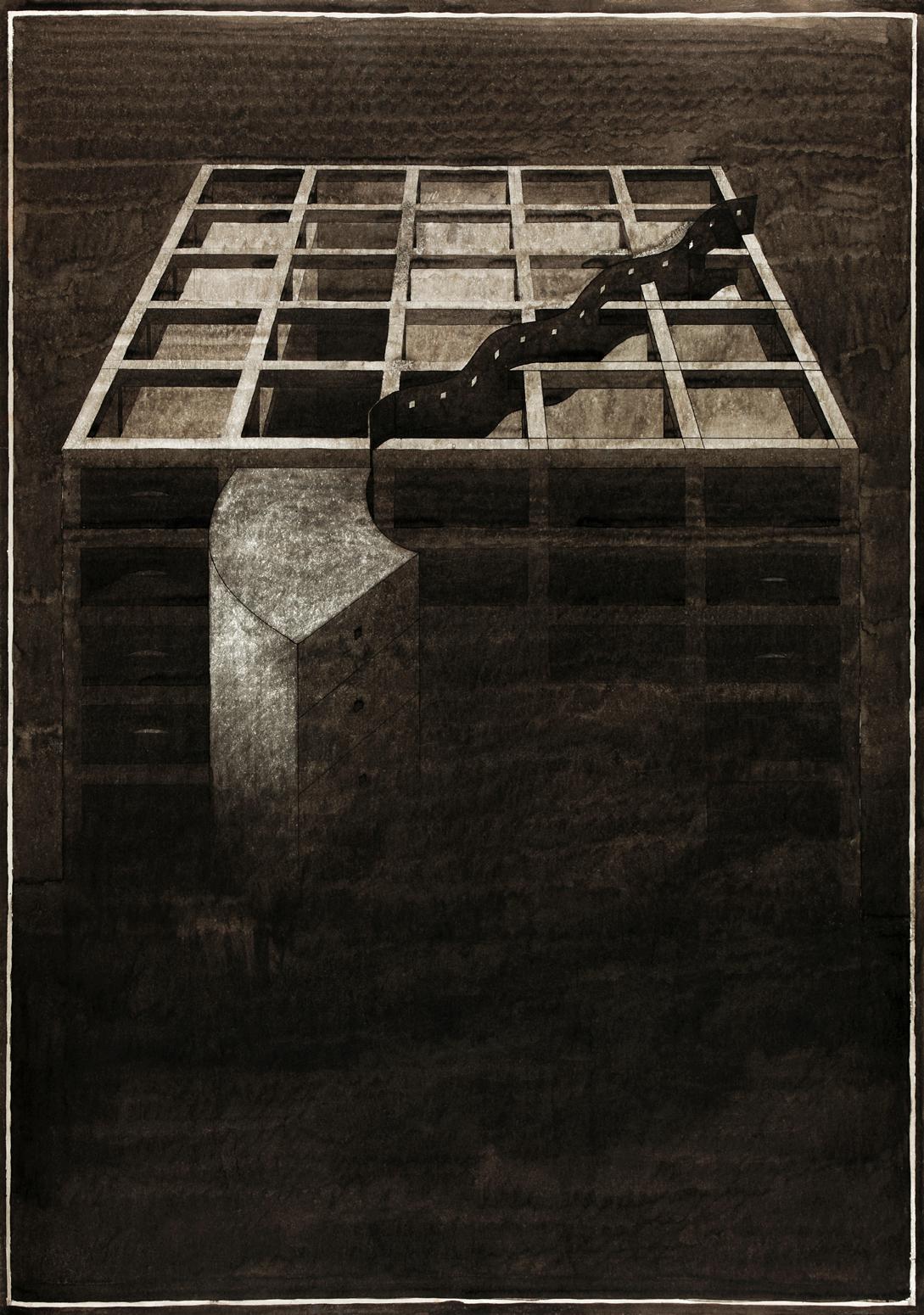

THE HOUSE WITH THE NON-ATRIUM 1985 Viktor Smyshlyaev

THE NON-ATRIUM BUILDING 1985 Viktor Smyshlyaev

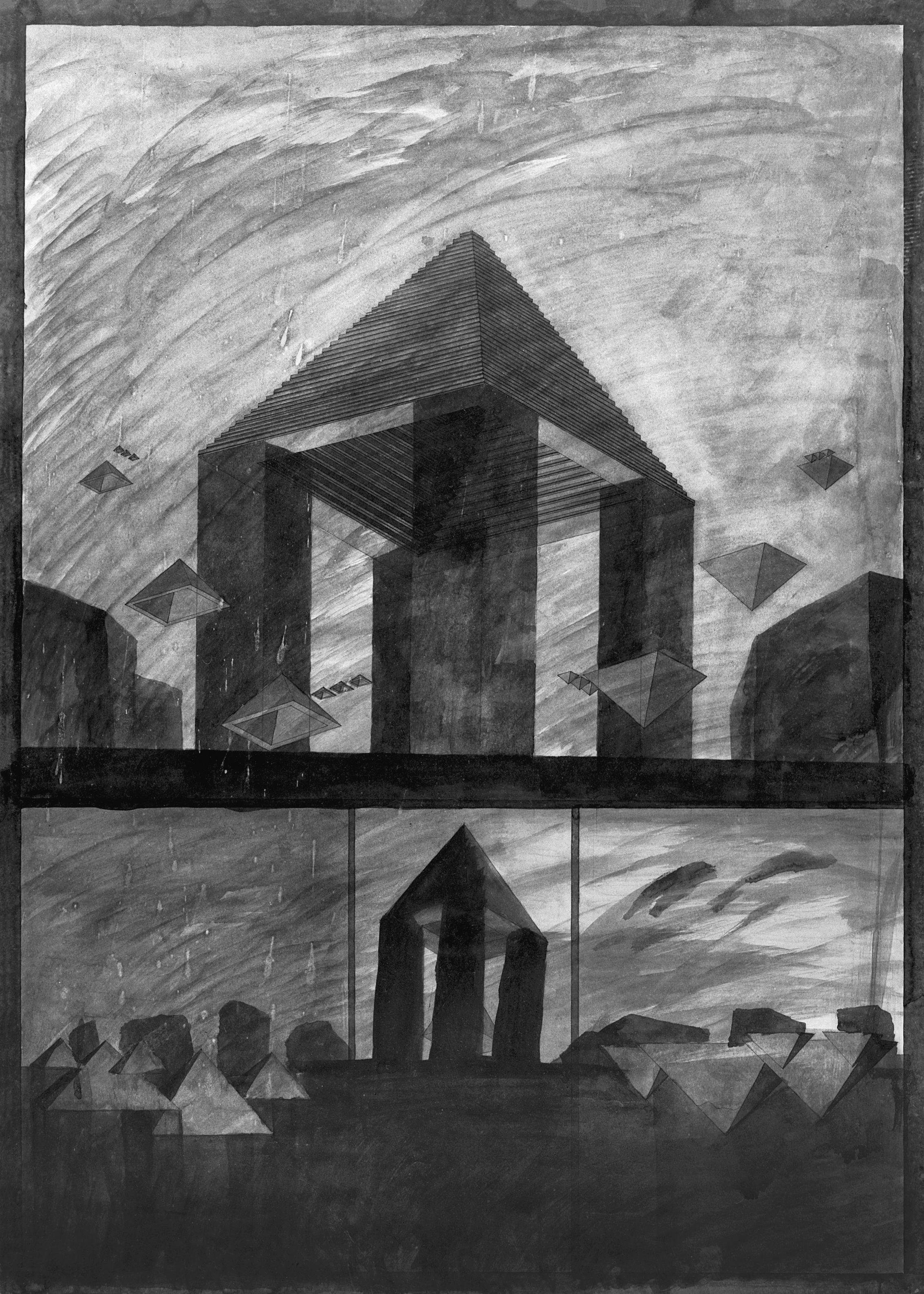

NAS & AVRORA right page THE BASTION OF RESISTANCE TO THE CITY 1985 Viktor Smyshlyaev, Yevgeny Burov, Slava Mizin

‘‘The pyramid, looming over the city, is filled with hidden threat. It will be terrible if it falls down. But if you change the mood, it will turn out to be just a large umbrella protecting against bad weather.’’

THE BASTION OF RESISTANCE TO THE BASTION OF THE RESISTANCE Initial version, 1985 Slava Mizin

THE BASTION OF RESISTANCE TO THE BASTION OF THE RESISTANCE Version 2, 1990/Later Slava Mizin

‘‘Sluggish volumes come out of the bastion, like paint squeezed out of a tube. It destroys the illusion of impregnability and reminding us of the constant resistance to the existing resistance.’’

DEVELOPMENT OF ZUBOV SQUARE Moscow, 1986 Viktor Smyshlyaev

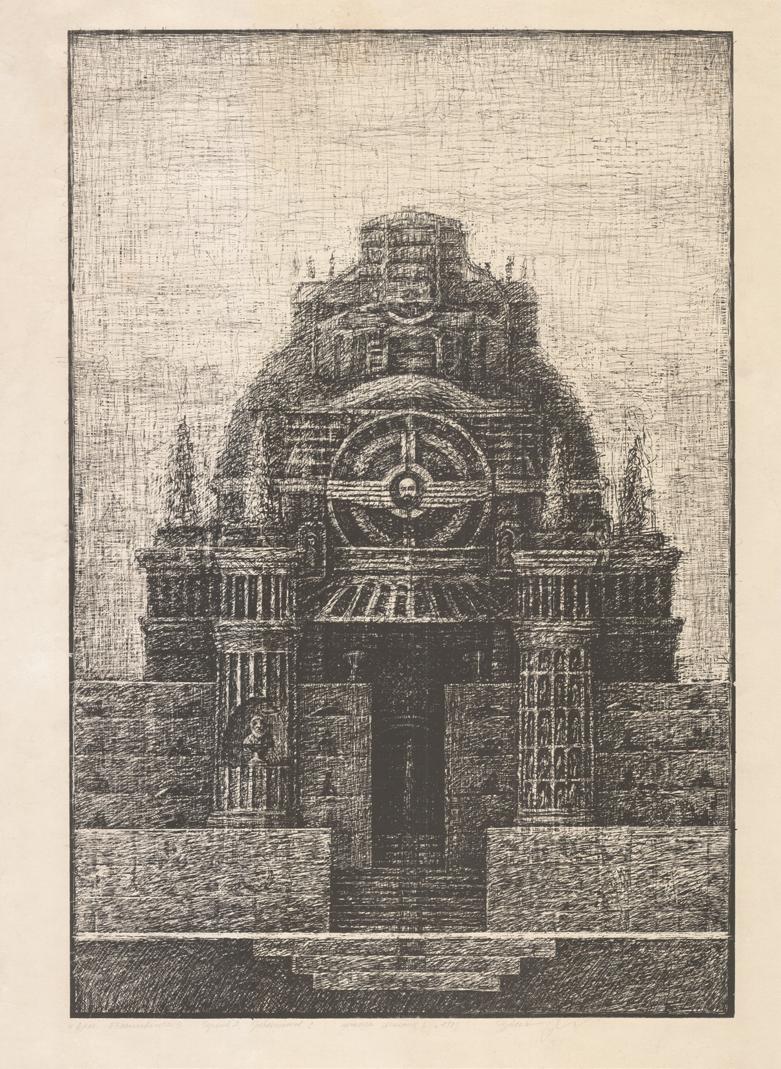

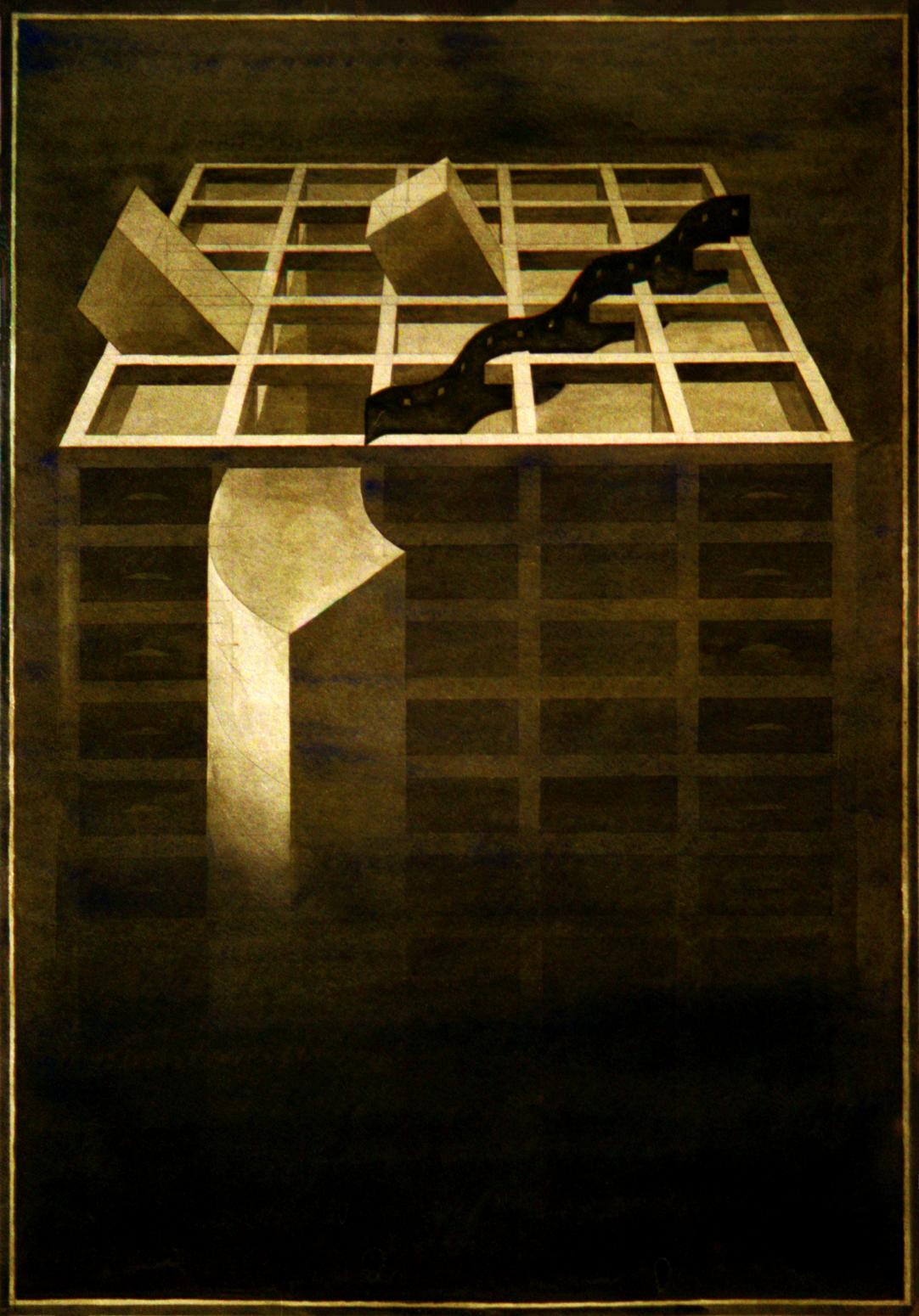

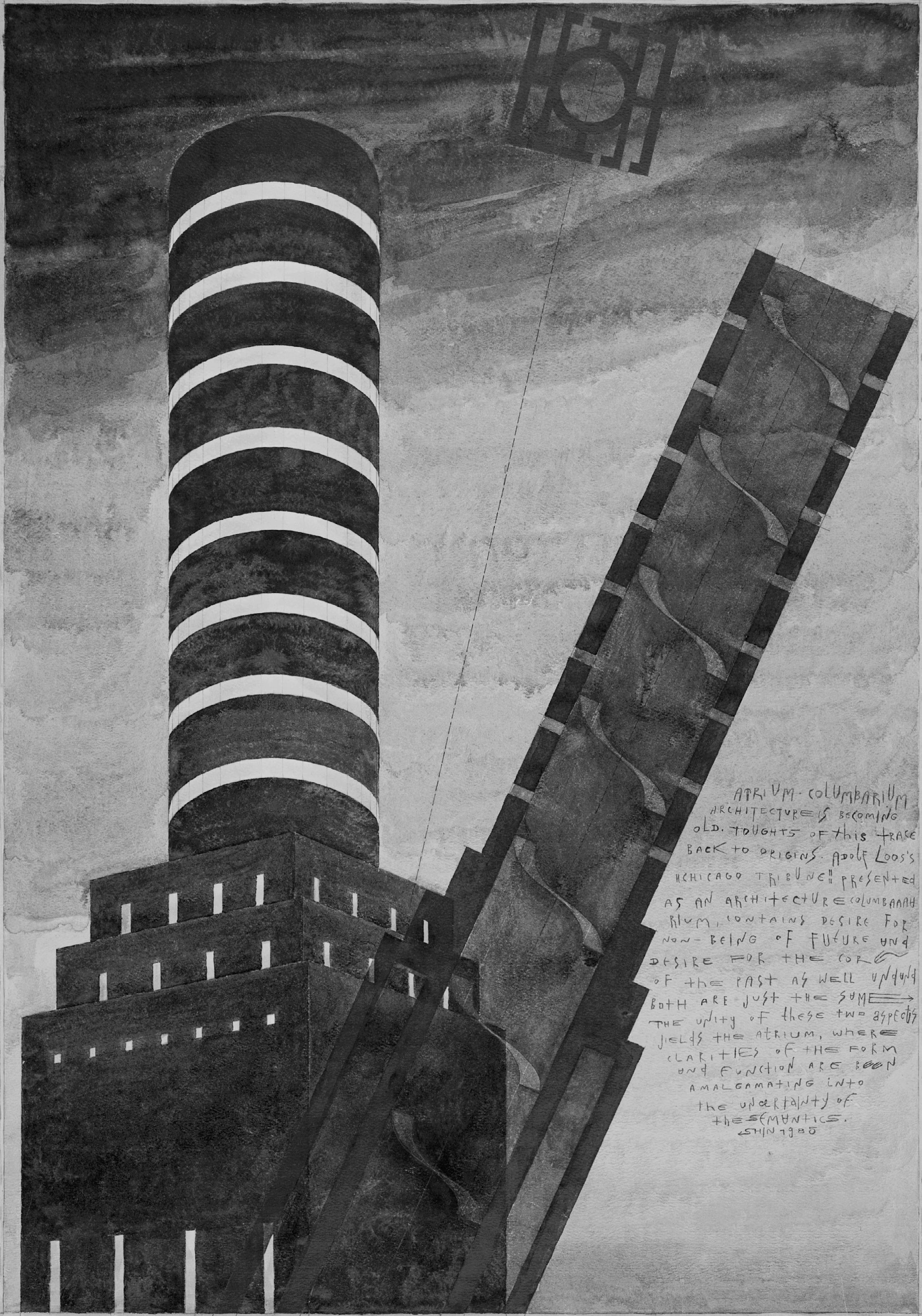

left page THE ATRIUM-CINERARIUM 1985 Viktor Smyshlyaev

‘‘The Architecture is dying. These thoughts get us back to the roots. Adolf Loos’s ‘Chicago Tribune’, presented as the architecture columbarium, strives both into the basis of the past and oblivion of the future. The unity of these moments creates the atrium, where the definite form and function combine into the suspense of meaning.’’

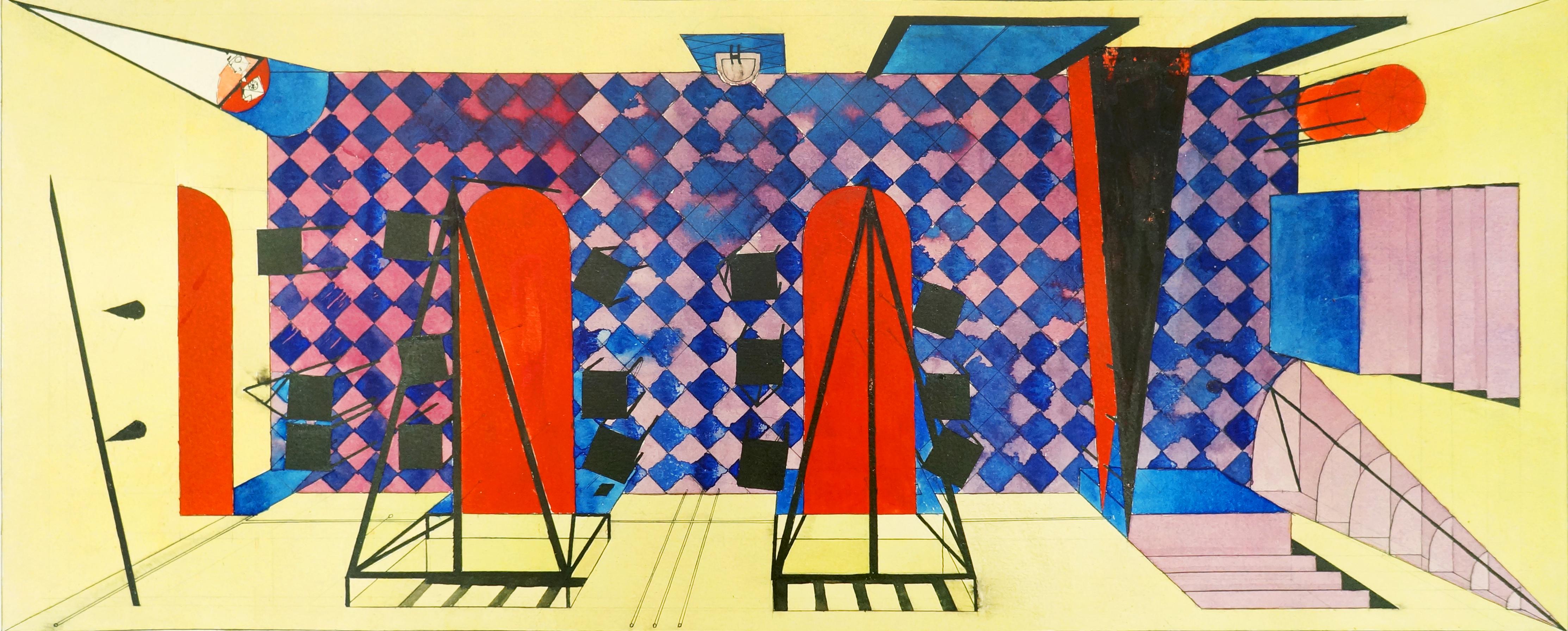

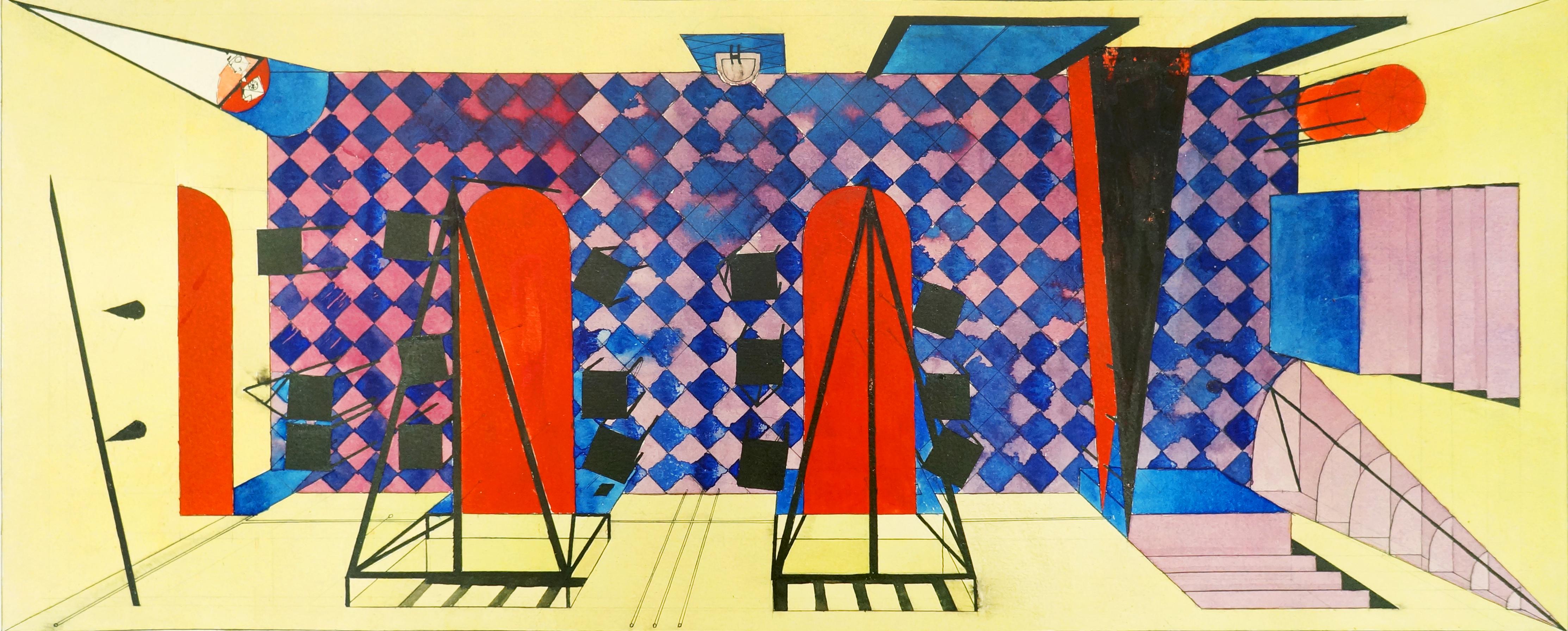

INTERIOR DESIGN OF THE BUFFET SIBSTRIN (NISI) 1984 Andrey Kuznezov

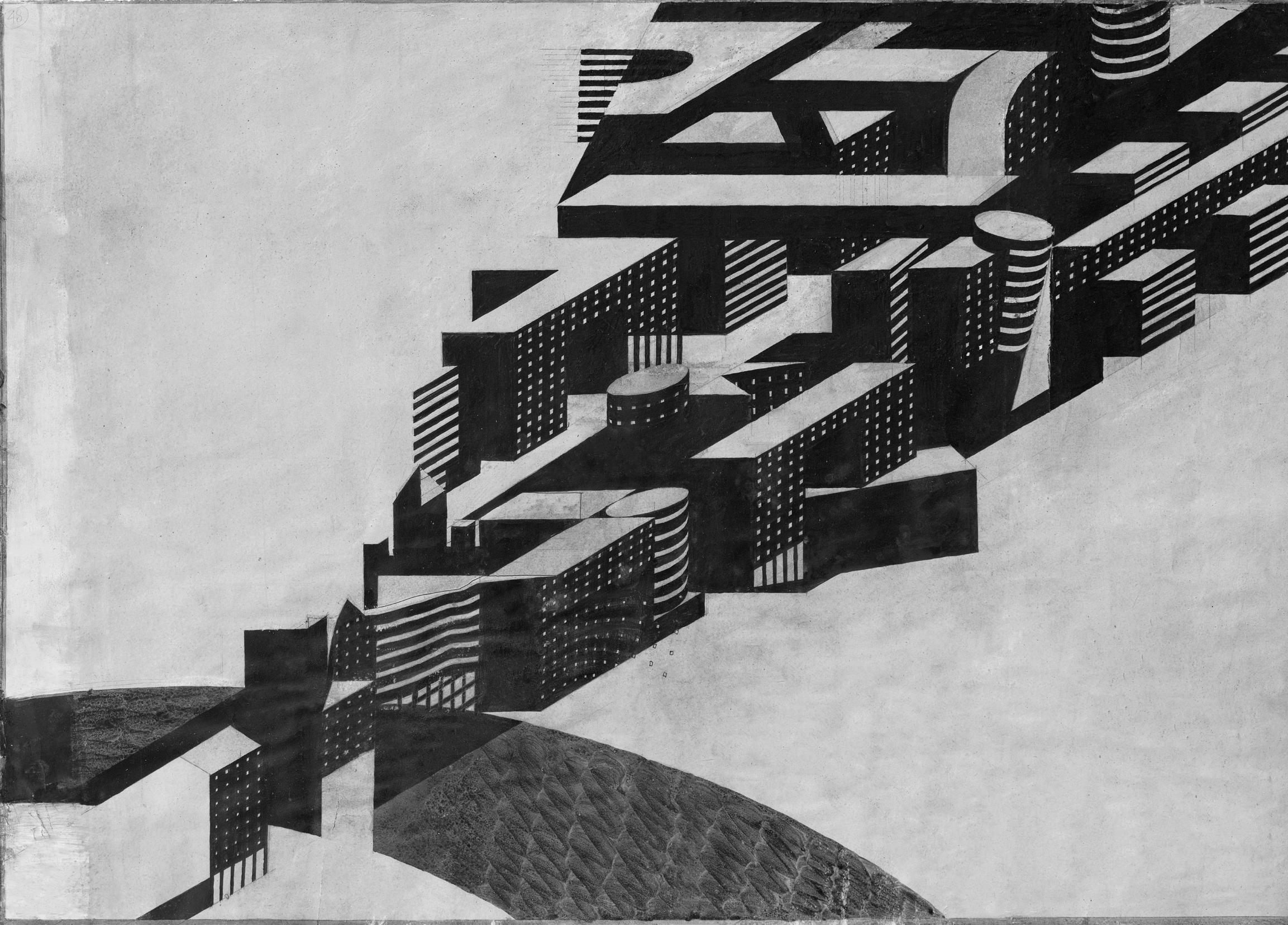

CONTEST PROJECT OF A RESIDENTIAL BUILDING IN ORDZHONIKIDZE STREET 1986 Viktor Smyshlyaev, V.Mizin, Yevgeny Burov, V.Kan

Residential building for 220 apartments with a service complex and public organizations. The volume is a series of blocks varying in shape, the dispersed setting of which and the free organization of the space of the first levels make it possible for mutual penetration with the urban environment.