2 minute read

For a complete list of international competitions, see : Yuri Avvakumov, Bumazhnaia arkhitektura Antologiia. Moscow: Garage, 2019. Pp. 13-15. For more details regarding the participation in these competitions, see an interview: Il’ia Lezhava and Ekaterina Golitsyna, Khrushchevskii Dvorets Sovetov, dom Narkomfina i bumazhnaia arkhitektura. In: Ustnaia istoriia. Recorded on August 9, 2016. Available at: https://oralhistory.ru/talks/orh-2064/text

metropolitan character. In what follows, I quickly summarize key features of (the Moscow-based) paper architecture and then use this summary to highlight most interesting aspects of its Siberian version.

As many late Soviet trends, paper architecture was a short-lived phenomenon. It lasted about a decade: starting in the end of the 1970s, it gradually dissipated by the end of the 1980s. The group of Soviet paperists (bumazhniki) was made up mostly by graduates from the Moscow Institute of Architecture (MARKhI) who designed their projects for various architectural competitions, organized throughout the 1980s by major international journals and professional associations – from The Japan Architecture and the British Architectural Design to the International Organization of Scenographers, Theatre Architects and Technicians (OISTAT) and the International Union of Architects3 .

Yuri Avvakumov – the chronicler and the archivist, the ideologue and the curator of this artistic movement – recalled later that Soviet paperists produced somewhere between 2,000 and 2,500 projects in 1984–19884. Il’ia Lezhava, an architect and Vice-President of the Russian Academy of Architectural and Construction Sciences, who was very instrumental in organizing first Soviet submissions to international contests in the 1970s, usefully pointed out a few years ago the main reason behind this radical proliferation of “paper castles”: We had a very good system of artistic training for our students [in the USSR of the 1970s-1980s]. But architecturally speaking, apart from the five-story apartment blocks, there was not that much for them to build in Moscow. Because of this gap, young people started expressing themselves in various architectural fantasies, often with a philosophical bent.5

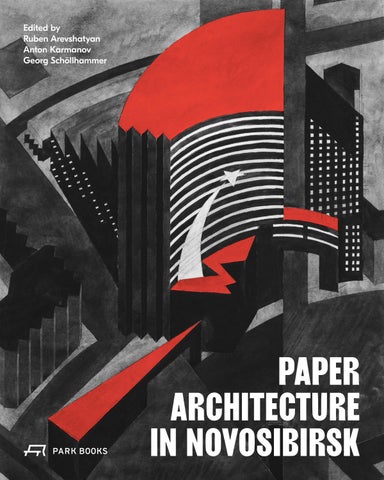

Never meant to be materialized, paper architecture emerged as a hybrid pictorial genre: a marriage of convenience between easel painting and architectural drawing. Neither urban landscapes, nor architectural blueprints, these paper fantasies were pictorial contemplations and figurative commentaries on structures (and their contexts), which were destined to remain unbuilt forever. Or, as Avvakumov puts it straightforwardly, “as a version of art for art’s sake, paper architecture is good as long as it does not have to be realized in practice…”6 The decidedly non-utilitarian, exploratory and compensatory nature of late Soviet paper architecture, emphasized by Lezhava and Avvakumov, is important. Indeed, paper architecture was an artistic speculation of the second degree; o ering imaginary projects that promised more imaginary projects, it filled the gap between available skills and unavailable opportunities for their realization.

Of course, there is little surprising in the fact that young architects with a lot of energy, free time, and no realistic prospective of implementing their own projects in real life would eagerly immerse themselves in the realm of architectural fantasies. What is unexpected is the popularity of these fantasies among their international colleagues. Within a very short time, Soviet paperists became leading