15 minute read

PLACE

from Civano

The Handoff to the Private Sector Mid-1996 to Mid-2002

(opposite, left) David Butterfield on the right, leading a community event in one of his developments. (opposite, right) David Butterfield, first developer of Civano

In February 1996, the City issued a Request for Proposal solicitation to qualify for and participate in the auction to be held in June for the 818 acres set aside for Civano. Only two companies replied: David Butterfield’s Trust for Sustainable Development (TFSD) and Arizona Public Service, one of the three large Arizona power generation companies.

As part of any Arizona State Land Department sale, an independent appraiser must set the minimum land value for the public bid. As one can imagine, this appraisal was subject to considerable debate. On the one hand, the State Land Department sought the highest justifiable estimate. On the other, given the estimated $9 million financing gap in the then project pro forma, the City hoped to have the State Land Department establish the lowest reasonable valuation. Laswick worked with the appraiser to ensure that he fully understood the requirements of the IMPACT Standards. As a measure of just how ambitious the development requirements for Civano seemed to a conventional real estate expert in 1996, the appraiser asked Laswick if he realized that “it would be possible to assign the land a negative value.” The appraiser’s reaction shows the institutional bias against any development prospect that did not conform to standard sprawl development. An important corollary point is that, in the estimation of this experienced appraiser, innovative prototypes like Civano would require some form of subsidy to achieve financial viability.

There is also a “road not taken” story buried in the public bidding process. John Wesley Miller relates that David Case, who will be introduced in the next chapter, first approached Miller and Arizona Public Service about forming a development team to go after the Civano RFP. When APS could not come to terms with the City on pre-bid conditions, Miller made Case aware of Butterfield, and the two joined forces, but with Butterfield remaining in charge. The departure of APS left Butterfield/Case as the only bidder, allowing them to purchase the property at the minimum appraised value: $2.3 million. One can speculate on just how different Civano might have been if APS had been one of the development partners. The financial issues that plagued Civano almost certainly might not have happened. With Butterfield, a strong proponent of New Urbanism, as a partner, one can speculate that Civano could have happened with New Urbanist planning and design, but far better funded.

APS’s interest possibly reflects that, in 1996, most large utilities were supporters of “alternative energy,” especially solar. It was an infinitesimally small factor in energy generation, but it was good public relations. The public loved solar. As the price of alternative generation—especially wind and solar— came down over the next two decades, utilities began to see a threat to their monopolies on energy generation and distribution. APS is now considered to be a ferocious opponent of renewables—especially when owned by private

users—and has been exposed financing the campaigns of candidates for the public utility commission who would support their position. With a developer chosen, they and the City reviewed final revisions to the Development Agreement. Once terms had been agreed upon, the Agreement went to the Mayor and City Council for approval. That approval was far from certain. While the Council was quite progressive, two of its six members, who were ardent environmentalists, did not support the proposed Agreement. The primary reasons were its distance from the central city with its employment base, and Civano’s middle-income market focus. The fact that there was no open land of Civano’s scale any closer to established employment centers, and most jobs lay in a band about midway between downtown and the site helped, but did not erase the “distance from jobs” concern. The commitment to 20% affordable houses over the life of the project failed to sway one dissenter. After some tense debate, the motion to approve the Development Agreement and certify Butterfield/Case as the developer narrowly passed 4-3. The sale of the land at the minimum “fair market” value and the fact that no bidding pushed it higher was significant. The winning bid equated to roughly $2,800/acre, or $4,000/acre of buildable land, if the mandated 30% open space set-aside is taken into account. At that time, buildable raw land on Tucson’s far east side was valued at roughly $6,000–$8,000 an acre, resulting in an effective discount of at least $1.15 million to the developer, a discount that could be directly attributable to the development requirements for Civano. This discount was seen as another way that the financial challenges that had been implicit in Civano’s planning from its conception were gradually being overcome. Fifteen years after the Kessler memo first outlined the ideas that should be included in what would become the Tucson Solar Village, all the components were in place to begin making its evolved descendant, Civano, a reality. Land; a clear Development Agreement assigning public and private responsibilities; professional studies showing that there should be a strong market for Civano in the Tucson region; a committed private-sector developer; two exceptional City officials to help the project’s passage through the regulatory and entitlement process: all these were in place. A public planning workshop, or charrette, was scheduled for September. Momentum could be felt, and optimism abounded. And yet, not quite six years later, the last two neighborhoods of the project would be broken away, and the IMPACT Standards softened. All this, even ORO Editions though Neighborhood One, fully incorporating New Urbanism and on its way to meeting the IMPACT Standards, was showing sustained sales and growing success. A new builder/developer, Pulte Homes, would embrace sprawl production housing standards for Neighborhoods Two and Three. During those

six years, no less than six different entities had responsibility for managing the development of the project—a remarkable fact, the impact of which on the project was profound. Any development project of Civano’s size would be negatively impacted by the frequency of management turnover Civano saw. In Civano’s case, we submit that impact was leveraged by the special nature of Civano’s history. Even if there had been one management group throughout the development of Civano, entitlement and development would have been a challenging process. What made this particular project so sensitive to the absence of continuity in the development process?

• Civano’s long history and the legacy of open public planning lead to a sense of ownership by many parties. There had been nearly ten years of visioning, open meetings, and planning efforts. A broad coalition of people had been brought into contact with the project, and each left their contribution in their own time. Unfortunately, each step in Civano’s evolution was too often seen as a diminution, if not outright abandonment, of the previous group’s understandings and expectations. By the time that dirt actually started to be moved on the Civano site, there were many people who felt they were the holders of the true vision, even if they bore no responsibility for the emerging built reality of the project. While their adherence to a single issue or the concepts of the past may have been laudable, this limited focus was no longer in balance with the broader and more interlocked goals of the project. • Lack of experience in developing a project like Civano. Civano was the first attempt to create a community of some 1,400 homes composed of three mixed-use neighborhoods to be planned and implemented with a combination of New Urban protocols and aggressive energy and resource conservation goals, and to be aimed at middle-market housing. • Lack of experience in marketing a project like Civano at its scale. Contributing to this complexity was figuring out how to market a development that was so focused on new concepts like sustainability and the New Urbanism, concepts still emerging into the broad public consciousness. While there were other projects that incorporated some of Civano’s environmental and social goals, none were of the same scale and none were aimed at the middle market, the province of production builders. • The complexities of public/private partnerships. In this public/private partnership, like most, the public side formulated policy, and the private side was held responsible for implementing it in both its broad strokes and details. The policy makers and advocates were not constrained by the discipline and pressure of time, interest payments, and the search for financing. The importance of having both private and public representatives in a

constant dialogue with each other, not just in times of crisis, took a while to learn. • The limited financial resources of the initial development team.

A NEW SET OF EXPECTATIONS

With the Trust for Sustainable Development certified as the developer and the Development Agreement approved, a new era began: the project had entered the province of the private sector. With that passage came new expectations, some obvious and acknowledged, others more subtle and unspoken. The responsibility for “making things happen” shifted from the City to the developer. Along with that shift came expectations that key project goals and schedules would be met. It was the private sector that had the expertise to implement and build this ambitious community in the real world. The developer was dedicated to the core ideas of the project, experienced and respectful of people who had been involved in its history. For many of them, the moment had arrived when this evolving idea they had helped mold would become a reality, a place in which many of them wanted to live. They felt that the right developer was in charge, one who acknowledged past promises, real or perceived. In the following sections, we will track the constant changes in the composition and strategy of the development management team, focusing on the causes for those changes and the impacts they had on the implementation of the project. It is important to remember Will Orr’s admonition that this ambitious project was an ongoing experiment that would need to be adjusted in its early stages. It would be in the first neighborhood phase that the various ways to achieve Civano’s goals would be explored. It was also during this phase that some of the key assumptions of this private/public partnership would have to be tested. Would the dual responsibilities, either stated outright or implied in the Development Agreement, be able to be implemented in the unforgiving and demanding world of the marketplace? ORO Editions

Civano Development/Fannie Mae 1999

Ownership Interest Fannie Mae/American Communities Fund (66%); Civano Development (34%) Lead Development Decision Maker Fannie Mae/Kevin Kelly Lead Planning & Design Rayburn Total Homes Sales for This Period (began in April 1999) 118 contracts by the end of the year; 13 per month on average

BECOMING A REALITY

1999 was the year that Civano finally became a living reality. The first section of Neighborhood One was completed. Site work began on the remainder of Neighborhood One, and the project site was a beehive of activity. Home models opened for sales, and the public response was enthusiastic. There was a general feeling, both within the development team and the City government, that sales momentum would overcome the delays of the last eighteen months and provide a steady and increasing cash flow to the development. No one could imagine that by the middle of fall, the project would once again be at a virtual standstill and in crisis.

THE BEGINNING OF HOME SALES AND THE GRAND OPENING

In early April, the public was invited to a “pre-opening” view of the nine model homes that had been completed. On the first day, over 600 people showed up to walk through the models and there was enthusiastic coverage in the local media. This was an astounding number for a housing development in Tucson, and the first indication that the project would, in fact, find success even in Tucson’s challenging housing market. The formal grand opening of the first neighborhood of Civano was held on April 16th. Fannie Mae senior management was there in force. Although invited, Vice President Al Gore could not attend, but did send a very appropriate and supportive letter that emphasized Civano being a model for the future. (See page 2.)

By the end of the year, 118 contracts were written for new homes. About thirty were for people who had been following the Tucson Solar Village / Civano project for years, and their “pent up demand” was finally met. The remainder of the sales were to buyers without a long association with Civano but attracted by its “different” look, the energy savings features, and by the ability to customize their home to a greater extent than was the norm for national production builders.

The strong sales were an enormous confidence booster for all the project stakeholders, though how those sales were interpreted differed widely. For the City, the strong sales did much to erase earlier frustrations that the grand opening was behind by months, as well as concerns about the impact of Fannie Mae’s ever greater presence and ownership position. With some frequency, doubts had been expressed about whether the development team would continue on or whether Fannie Mae would take over completely. The strong sales pushed those doubts to the background, and there was a newfound confidence that the project would generate an income stream that would make for a future far less turbulent that the past two years.

The benefits to the project of this new confidence were immediate. The entitlement reviews for Phase Two and Three of Neighborhood One were accelerated. Optimism based on the strong sales was a factor, but now, as homes began to be constructed, reviewers could go the project site and see what they were being asked to approve. This tangible “look and feel” won many over. The promise in the Development Agreement of expedited reviews looked to finally become closer to a reality. With the enthusiastic sales, the City started to look beyond Neighborhood One and began pressuring for the start of planning for Neighborhoods Two and Three. In May and June, a series of workshops were held to start outlining the general approach to be taken for the next phases of the project. The workshops were notable for their inclusive nature, and especially for the strong support and attendance by City planning, zoning, and engineering personnel. There was general agreement that Neighborhoods Two and Three should build on the protocols of Neighborhood One, while adding on some of the more challenging site engineering concepts that just did not have support during the earlier entitlement reviews, notably those addressing surface water management. In Neighborhood One, Rayburn and Moule & Polyzoides continued their efforts to create a body of design codes that would solidify the new urbanist intent started in the 1996 charrette. Street standards and the first formbased codes were drawn up. But as with the earlier formalization of the site planning process, their formal adoption as project guidelines or requirements ran into resistance from the senior members of the project ownership. DARKER CURRENTS: MONEY TALKS With Case’s departure from the project at the end of 1998, Fannie Mae became the majority owner. Kelly remained the managing partner, in charge of day-to-day decisions and general strategy. Technically, Fannie Mae was to be a passive partner; but with greater frequency Fannie Mae used its majority ownership position to insert itself into day-to-day operations. This tendency only accelerated as Fannie Mae’s continuing funding contributions grew throughout 1999. ORO Editions The downside of the unusually large and discounted lot options that had been used to lure builders into the project at its inception now came to the fore. Though the strong home sales were accelerating builders’ takedown of their optioned lots, the locked-in prices were just covering the project’s land development costs. There was little left over to cover the development team’s

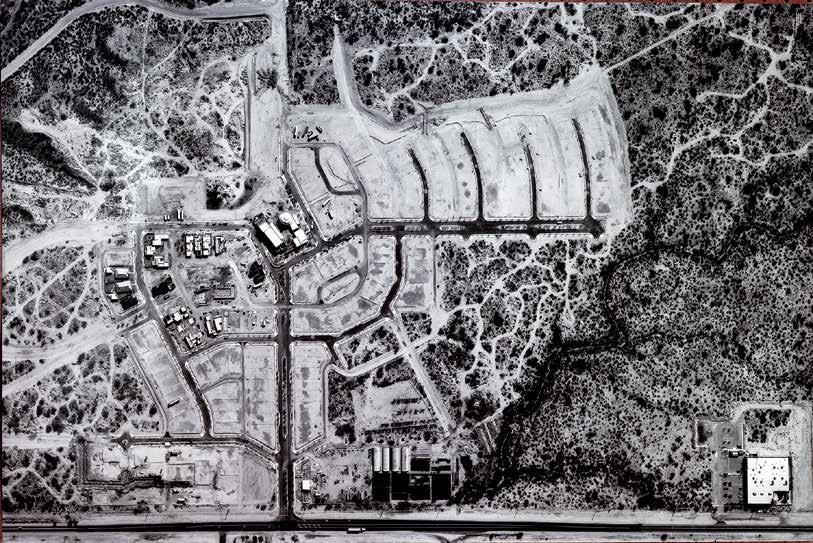

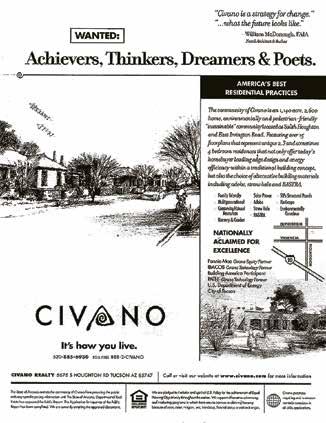

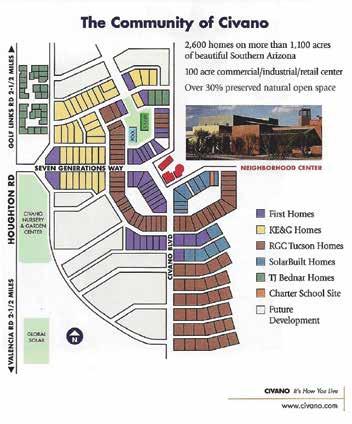

(top) An aerial view of the site with the Neighborhood Center in the middle and builder model homes under construction to the left of the Center. North is to the left. (far left) A map showing the first phase of Neighborhood One, with the homes being built by the various builders. (left) The first sales advertisement for Civano once model homes were ready. It stresses quality and the difference between Civano and standard production homes.

ORO Editions

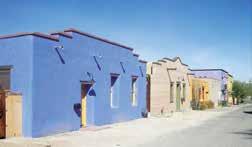

The Charrette preparation process focused on the study of traditional and new traditional ORO Editions adobe and rammed earth buildings in the 19th century Tucson neighborhoods that they were built in. Before the senseless demolition of 300-plus historic buildings and two plazas during the early 1960s, Downtown Tucson was the equal of Santa Fe in terms of its built heritage. Happily, in 1996 there were many historic adobe houses to study still standing in the Presidio, Barrio Historico, and Barrio Viejo neighborhoods.

Over the centuries, Tucson’s traditional form had been developed in response to living in the desert with limited material and energy resources. Its lessons had been abandoned since the 1950s. It was providential that the Civano charrette team would have recognized the urban and architectural principles that had enabled sustainable living in this climate and culture over the centuries. They adopted them as the basis of developing the image, place-character, and environmental performance of the most ambitious sustainable project.

These modest, one-story buildings had been built before the petroleum era. They were ORO Editions arranged along walkable streets and packed tightly around well-shaded private patios on urban blocks. They were highly energy and material efficient. Their neighborhoods featured a jobs-housing balance, diverse building types and uses, high affordability, and excellent service by various transportation modes. After studying them in detail, the architectural team concluded that their performance exceeded the standards of the Civano Protocols by 50% and the typical subdivision production house standards by 100%.

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

The foundational sketch of Civano’s image: The Neighborhood Center viewed from Seven Generations Way. Courtesy: Moule & Polyzoides