Artists have always looked to the art of the past — although the nature of artists’ responses to what has gone before has always been wildly varied. At the same time most museums see part of their role as encouraging, informing or engendering contemporary artists. Indeed, many of the Ashmolean’s collections were specifically assembled as teaching tools — most notably, perhaps, those donated to the Museum by John Ruskin and used by him in his own teaching. More recently, and increasingly, contemporary artists have assumed a different role within historic museums — as interpreters and activators, commentators on historic collections; allies in the museums’ mission of encouraging contemporary audiences to look anew and with different eyes at their historic collections.

When museums and contemporary artists engage most fruitfully, of course, all these things happen at once, and light is shed in all directions. The new Ashmolean NOW exhibition series hopes to generate such creative, multi-faceted conversations between past and present, between artists and audiences and between the works of art themselves. Through this series we invite early- to mid-career UK-based artists into the Museum and ask them to look, think and create work in response. The first exhibition of the Ashmolean NOW series is dedicated to contemporary painting. It juxtaposes the work of two artists, by dividing the exhibition space (and this book) into two: Daniel Crews-Chubb x Flora Yukhnovich.

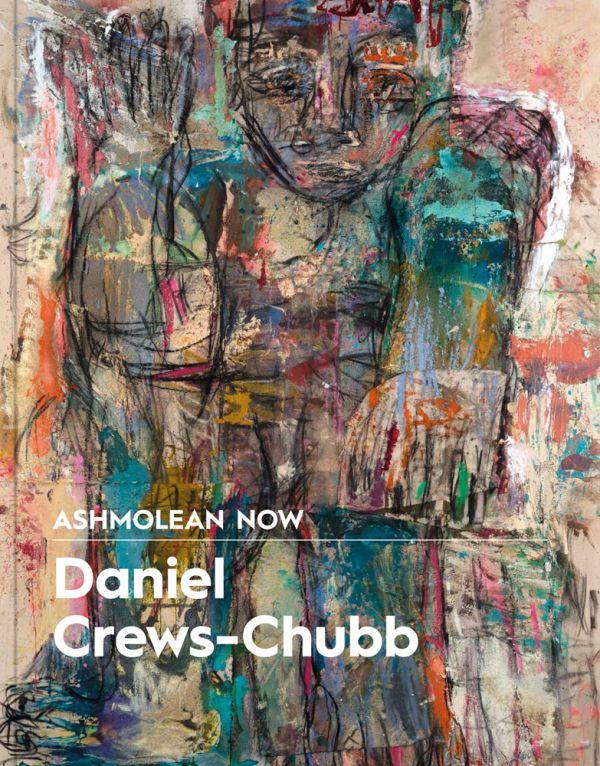

Daniel Crews-Chubb has garnered recognition for his innovative, experimental and expressive collage paintings, which interrogate motifs and archetypes of art history, while also linking to the legacies of twentieth-century

modernist paintings. In his new series, Immortals, which is informed by depictions of deities and other non-human figures throughout history, Crews-Chubb explores the divine privilege of immortality. Inspired by works in the Ashmolean’s collections as well as external sources, Immortals opens a space to consider spirituality and the purpose of artistic practise in our contemporary moment. The Museum’s rich and diverse collections provide a fitting context for Crews-Chubb’s dynamic paintings, creating new dialogues between the past and present, sculpture and painting, East and West.

My thanks are due to Lena Fritsch, the Ashmolean’s Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, for devising and curating the Ashmolean NOW series, and for all her work on this exhibition and book. We are enormously grateful to Andy and Christine Hall, and Neil Simpkins and Miyoung Lee, who generously support her post. We also offer sincere thanks to Christian Levett and those who wish to remain anonymous, to the Patrons of the Ashmolean Museum, and to Ben Brown for their support of the Ashmolean NOW series. This exhibition and catalogue of Crews-Chubb’s work could not have been realised without the support of Timothy Taylor gallery and we are truly grateful for their close collaboration. We also owe a debt of gratitude to Sydney Smith for her insightful essay, and to everyone at the Ashmolean who has worked tirelessly behind the scenes to make this exhibition possible. Above all, we would like to thank the artist, Daniel Crews-Chubb, for his trust — it has been a great joy and honour to work with him.

Xa Sturgis

For a contemporary artist, Daniel Crews-Chubb has an unusually ambivalent attachment to the ‘now.’ While his work is highly experimental, pushing the boundaries of paint as a medium and exploring the complexities of personal identity, his new series of Immortals (pp.32–41) are also rooted in forms of expression that belong to the past. These mixed-media paintings reach back into antiquity to sources as varied as Mayan funerary objects, Roman and Greek sculpture as well as Hindu temple guardians in order to find inspiration from art that acted as a tool for devotion and a link to the divine. The sketchy outlines and enigmatic expressions of the monumental figures in the Immortals series reflect what the artist describes as his ‘strange relationship to history.’1 For Crews-Chubb, history is mysterious and subjective, something that we can only apprehend through glimpses of the visual and material culture that has been left behind. The Immortals series is inspired by traces of the past, but uses a contemporary palette and a mixture of materials from oils to spray paints that catapult the work into the present. The figurative motif mimics certain formal qualities of historical depictions of gods, goddesses and deities – such as their scale and posture – whilst their identities remain elusive to the viewer, hovering on the level of the suggestive.

While Crews-Chubb began his series of Immortals last year at the Ashmolean’s invitation to respond to its collections, this new body of work is also informed by his long-standing desire to explore his own spirituality. The title of the series refers to the divine privilege of immortality, and the figures in these paintings are inspired by depictions of gods and goddesses throughout history – of which innumerable examples can be found in the collections of the Ashmolean. Unlike other painters inspired by mythology, such as the American artist Cy Twombly (1928–2011), who framed his abstract compositions with

titles like Leda and the Swan or Apollo, Crews-Chubb’s Immortals open a space to consider how we might reimagine spirituality in our contemporary moment. The figures in the paintings constitute the artist’s own ‘invented mythology’, as he puts it, taking inspiration from classical sculpture and ancient artefacts to offer artwork that he hopes could one day be offered as gifts to gods we haven’t yet named.

In these paintings, ink, sand, charcoal, pastel and impasto oils create dense forms of crouched figures that stoop into the frame, with their feet and the crowns of their heads pushing right up against or out of the top and bottom margins. The scale of the standing figures is precisely 1.5 times the size of Crews-Chubb’s own body, a formulation that establishes the Immortals as larger-than-life, but not out of reach. They function as demi-gods, suggesting something of the human as well as the divine.

Daniel Crews-Chubb was born in 1984 in the East Midlands industrial town of Northampton. At school, he struggled with dyslexia. His favourite subjects became physical education and art, which functioned as outlets for his energy

Daniel Crews-Chubb, Forest (blue, green, pink), 2018. Oil, acrylic, charcoal, ink, spray paint, pastel, coarse pumice gel and collaged fabrics on canvas, 200 x 500 cm

and creativity. With ambitions to become a painter, he moved to London to attend the Chelsea College of Arts, where he discovered that painting as a medium was ‘out of vogue’. The young artist clashed with professors and students who pushed him to work more conceptually in new media like installation and video. After graduating in 2009, Crews-Chubb enrolled in the newly-established Turps Art School, which offered a Painters Studio Programme that finally emboldened him to delve into the possibilities offered by his chosen medium among an experimental group of peers.

With this new-found sense of freedom, Crews-Chubb developed the intensely physical mixed-media painting style that has become his hallmark. In his work, paint is smeared with the fingers, scratched with a stick, glopped on straight from the tube, sprayed from a can, and mixed into sand or pumice gel. The combination of this ‘wild’ use of materials with historical subject matter is a recurring characteristic of his work, perhaps informed by his formative experiences in art school, where he felt his practice was more in conversation with voices from art’s past than the contemporary Zeitgeist. In paintings like his 2018 series of Beasts and Forests, panoramic landscapes are populated by fantastical creatures and their mysterious human counterparts. Using imagery

This is a shortened version of an in-conversation between artist Daniel Crews-Chubb and exhibition curator Lena Fritsch. It started over email on 23 February 2022 and was continued in person at the Ashmolean café two days later. The artist had visited the Ashmolean and looked at works at the Museum, but he had not yet begun working on his new paintings for the exhibition.

Lena Fritsch: Let’s start at the very beginning: You were born in Northampton in 1984. What are your earliest art memories — how did you become interested in art?

Daniel Crews Chubb: For as long as I can remember, I have always been interested in art and visual language. I’m severely dyslexic and as a child, I had trouble reading and expressing myself vocally. Drawing came naturally — it was a much easier way for me to express myself.

Do you remember when and how you decided to become an artist?

I’m from a large industrial working-class town and art never seemed like a career path that I could pursue. It was not until I started visiting museums and art galleries when

I got a little older, in my late teens, that I decided to go to art school. When I started to study art at Chelsea College [of Art and Design], it all became a little more possible.

Many of your paintings and drawings are inspired by elements of ancient sculpture, archetypes of art history from all over the world as well as modern painting. Where do you usually get your inspirations from?

I often go and visit museums, looking at art and artefacts made by other artisans from different cultures and periods in history. I’m really interested in the idea of syncretism and how idea systems, beliefs, religions have amalgamated, merged and been altered through intercultural exchange. I like to find links between cultures. The Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, Aztecs and Mayans all had fertility, protector and warrior deities for example.

You incorporate these different inspirations but always manage to create something new — your works convey a unique ‘Daniel Crews-Chubb aesthetic’. Could you tell me a bit more about the artistic process? How do you work in your studio?

My style has evolved over the years. Essentially, I’m now a mixed media artist. I like to throw a lot of ‘stuff’ at the canvas which creates a really strange, visceral surface. For me, the surface is as important as the image. There is an array of materials that I use. I put them together in an ad-hoc, makeshift manner, where no mark or material has a hierarchy. There is thick impastoed oil paint, scratchy charcoal lines, but I also like to use spray paint, ink, and mix some sand and pumice gel in there to build surfaces. The collage element of my practice has also become very important. If I make a mistake or if there is an element of the picture that I don’t like, I can simply stick a new piece of canvas on top and redo that area.

Many of your paintings feature fantastical figures that appear like a mix of human, animal, sculpture, etc. Could you tell me a bit more about your interest in the ‘human-like‘ figure?

My figures pose more questions than they answer. I think they are, essentially, extensions of myself, my mood and my existential doubts, questioning why I’m here and what my purpose is and the absurdity of it all. I see them as my creations — not too dissimilar to Frankenstein’s monster.

They have become their own thing, and they have their own identity and are far removed from their initial inspirations. This happens naturally in the making; an idea can quickly change while I’m working. I might be looking at a depiction of Zeus, Hercules or Venus, but a simple ‘accident’ or a spill, might change the direction entirely and it may become more animalistic or more abstracted.

You just used the word ‘monster’ and earlier we talked about how something that is ugly can be ‘aestheticised’ in art and become ‘beautiful’. What does beauty mean to you and how would you define ‘beauty’ in your work?

I try to find an aesthetic that incorporates ugliness. Beauty without a little bit of ugliness or a little bit of grunge is almost too beautiful, if you get what I mean? It doesn’t feel real enough, life itself is beautiful and ugly, and you can’t have one without the other.

It is raw. With my work, I’m trying to find this balance. I’m trying to display a kind of pure beauty which has ugliness within it. [laughs]

We visited the Ashmolean’s Western Art Print Room together a few months ago, looking at works on paper by Albrecht Dürer, Thomas Rowlandson, Antoine Coypel, Audrey Beardsley, and so on (p.30). Today you saw various works on display in the Museum. Are there any works in particular (or specific type of works) that you currently find interesting or inspiring, and if so why?

There are so many things in the Ashmolean’s collections that I’m interested in. Looking back at these depictions of mythical creatures and depictions of gods and goddesses, to recreate them and to think about how they can be important now is really exciting to me. I see this as a passing on of knowledge. Looking back at previous depictions, learning something through their creations and making something of my own for now really excites me.

I’m always drawn to non-human creatures or beings: humanoids, therianthropes, hybrids, deities, something a bit mystical or ‘other’. I’m also interested in what art was to artisans from ancient times and ancient cultures: works of art were offerings, to emperors or to the gods. Artisans would try their hardest to make an interesting

and beautiful object as a sacrifice, as an offering, as a rite of safe passage from this life to the next. And I think, this is a beautiful idea: art as a gift, to present to the gods. In some ways, we have regressed as a species — science and spirituality were much more closely linked for many ancient cultures. With my work, I’m trying to find my own place, it’s a personal journey.

That’s interesting, and I agree that science and spirituality were not as divided in the past as they are now. How ‘spiritual’ is your art to you — as many of your paintings are linked to or inspired by ancient gods and goddesses, do you see them as related to this idea of offerings that you just mentioned?

There is a lot of conflict in my work that stems from conflicts and contrasts in my life. I don’t follow an organised religion but I am spiritual. It’s an absurd existence: essentially, we don’t know our purpose or the reason why we are here. Maybe my works are my offerings to the gods, I just don’t know it yet! To create, is the most human thing you can do, whether it be a painting, a piece of music, a cake or a poem. I see my works as my ‘creations’: ‘creatures’ with their own identity.

This is a shortened version of an in-conversation between artist Daniel Crews-Chubb and exhibition curator Lena Fritsch, in the artist’s studio in London on 17 February 2023. At this time, he had finished most of the paintings for the exhibition at the Ashmolean.

Lena Fritsch: It’s great to be in your new studio and to finally see your new paintings. In the end, which aspects of the Ashmolean collection inspired these new creations?

I tend to mainly look at ancient art and artefacts because there is a particular energy to it. I can be attracted to an object for many reasons. It can be a stance, a decorative headdress or even simply the way it has eroded over time — the loss of a limb, or patina caused by aging. A lot of my work looks at sculpture. For example, Immortal III (red, green and pink), 2022 was inspired by the dismembered cast of a pedimental sculpture from Eleusis (p.24) and a tilted Small Head from 2nd or 3rd century Ghandara (p.52), both from the Museum’s collection.

I’m drawn to non-human things, but also the repetition of the figure throughout history. I looked at deities, such as Venus, but struggle with the Greek and the Roman

depictions, because they look too similar to us. Venus is a beautiful woman, Hercules is a beautiful man. When it comes to gods, it is the unknown that interests me: the mythical and supernatural. I like to look far back and have been really drawn to depictions of gods from other ancient civilisations, such as the Aztec and the Mayan. They were quite imposing, monstruous and surreal. I was drawn to the Figure of a female with elaborate headdress (possibly a yakshi) (p.22) in the Museum’s collection, and I also liked the almost cubist arrangement of the figure in Upper part of a plaque with deity wearing a multiple horned crown (perhaps the goddess Ishtar) (p.24).

I am like a sponge, taking in and absorbing. At some point, it all spurts out and by abstracting the figure, destroying and rebuilding it, this allows me to create an allusion of a figure we have never seen before.

The deities you are interested in, and the figures you then create are all quite fantastical.

Yes, definitely. Fragment of a frieze showing Leda accosted by the god Zeus in the guise of a swan (p.53) was another piece I looked at for inspiration. Three Immortals (ultramarine blue), 2023 was inspired by the