6 minute read

EXTENSION EDUCATION

By Catherine Wissner, UW Extension Educator

How To Grow Tomatoes and Peppers Successfully in Wyoming

Advertisement

Growers don’t need a greenhouse to grow vegetables successfully in Wyoming, but a few tricks will help get great yields.

On average tomatoes and peppers should be yielding 10 pounds per plant. Getting this kind of production takes a couple of easy tricks.

Growing season and seed starting

It helps to know how long the average growing season is for the area where one is growing. The growing season technically starts after the last frost and lasts until the first frost.

Most of Wyoming will have around 112 days during the growing season, with some areas in the Mountain West seeing only a short 50 days. Each year’s growing season will vary, but growers should plan on an average of 90 days.

Starting from seed opens up new opportunities for the vegetable varieties growers can buy at the store.

A seed packet will have a days to harvest or maturity number listed, which should be well below 90 days –sweet corn should be around 70 days – for Wyoming.

Tomato seeds are fast to germinate – about four to five days – whereas peppers can take 14 days or more. Add 14 to 21 days for the plant to get to transplant size of four to six true leaves.

At transplant size, growers should start to harden the plant by taking it outside on nice days, then back into the house at night until they can plant outside for the growing season.

There are varieties of tomatoes that do much better in Wyoming. These will have a harvest number of 70 days or less and are typically around eight ounces.

While many love beefsteak tomatoes, they need an exceptionally long growing season which doesn’t fit Wyoming conditions.

Growers should skip this variety.

Watering and fertilizing tricks of the rams,” she added.

The best and most efficient way to water a garden is with a soaker hose or drip tape. Keep the water on the ground and not up in the air.

Another must-have tool for successful gardening is a water timer. Vegetables are not drought tolerant and must be watered consistently every day or every other day to produce, so a timer is a garden’s best friend.

Tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, green beans and watermelon all love very warm soil, around 85 degrees Fahrenheit. This is hard to achieve in Wyoming, but not impossible with the help of black plastic laid over garden soil and irrigation infrastructure placed under the black plastic. This also creates a weedfree, water-wise garden.

The fertilizer used in a garden is very important. The first number on a box of fertilizer is the nitrogen content.

For a vegetable garden and tomatoes, it should be 10 percent or less. Excess nitrogen will cause huge growth and attract insects, especially aphids. If nitrogen is high, growers should reduce fertilizer and hose off the bad bugs.

Never use insecticides in a garden, they will kill pollinators, which are a grower’s best friends since they kill unwanted bugs.

When amending the soil for a vegetable garden, avoid using manures. Manures can be contaminated with weed seeds; have excess salt, which makes manure “hot” and harbor a host of unknown bacteria and parasites.

Catherine Wissner is the University of Wyoming Laramie County Extension horticulturist. She can be reached at cwissner@uwyo. edu or 307-633-4480.

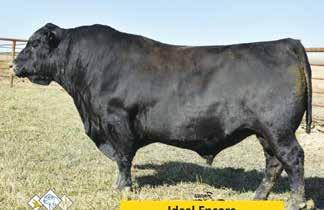

Large, successful test

This year’s test was the largest to date, featuring 142 rams from 29 different producers across Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota and Oregon. Four of the 29 producers were juniors, under the age of 18.

Koepke explained the five-month test evaluates average daily gain; fleece data including grease fleece weight, clean fleece weight, staple length, micron and coefficient variable; carcass data including loin eye area and back fat; scrotal circumference and visual scores including face wool, belly wool and wrinkle.

“This year was exciting due to the fact we had more producers and more rams participate than ever before,” stated Koepke.

“This gives us great hope for the future of the genetics in our region.”

“As always, when we have a test with commingling animals, we are bound to have some issues,” she continued. “I believe this year we were very fortunate in how healthy our rams were. We have worked really hard at finding better feed resources to help with the cost of the test and to keep the rams in good health.” Ram test indexes Koepke further explained UW uses two specific indexes for the test.

“In the beginning, the first index – the ROM Index – was created by the Rambouillet Association. It is very specific to the Rambouillet breed and judges other breeds harshly,” she said.

The second index, according to Koepke, is the Wyoming Index, which focuses on traits all breeds should strive to improve on.

“In addition to each index’s requirements, rams must have at least 0.55 pounds per day on test; produce a minimum of nine pounds of clean wool, with a minimum of four-inch staple and the wool must not be coarser then 60 – 24.9 microns – on the side or 56 – 27.84 microns – on the britch,” she explained.

“When core samples are collected, instead of a side and britch sample, no skirting should be done, and the critical value is 23.77. The face covering must not exceed a score of 2.7, and the wrinkle score must not exceed a score of 2.5. All rams must be genotyped at Codon 171, with a result of QR or RR being required to certify,” she concluded.

Hannah Bugas is the managing editor for the Wyoming Livestock Roundup. Send comments on this article to roundup@ wylr.net.

MUD continued from page 1 or move around less to find forage, resulting in lower feed intake.

“With mild conditions of just four to eight inches of mud, cattle dry matter intake is reduced by 15 percent versus what it would be under the same conditions without mud,” Halfman states. “When severe mud conditions are present – one foot of more – dry matter intake plummets by 30 percent.”

He shares from a feedlot perspective, when cattle are standing in four to eight inches of mud, gain can decrease by nearly 15 percent, and if they are standing in belly-deep mud, gain can decrease up to 25 percent.

“Consequently, the negative impact of mud on feed efficiency can result in up to a 56 percent increase in cost of gain as more days on feed are necessary to reach finish,” Halfman says.

He adds, “It’s no wonder it becomes challenging to maintain good body condition on cows and desirable weight gains on calves when mud is all around.”

Calving concerns

Unfortunately for many producers, wet and muddy conditions often overlap calving season, which can present a number of different problems for cow/calf pairs. Michigan State University Extension Specialist Jerad Jaborek published an article on April 1, noting mud stuck on udders has the potential to spread disease, compromise the health of nursing calves and cause calf loss.

Halfman further notes mud can decrease the insulative properties of a haircoat, which is of increased concern for newborn calves born in muddy conditions, especially when it’s cold.

“Calves can become chilled by mud, trapped in it or sickened by the pathogens thriving in it,” he says. “This is why it is important to closely monitor calving, routinely check cattle and move cow/calf pairs to fresh pasture soon after calving.”

Jaborek also points out muddy conditions will further increase the already high energy requirements of cows and heifers during gestation and lactation.

He cites a 2021 study conducted by Ohio State University, in which cows and heifers were kept individually in un-bedded pens with 9.3 inches of mud or in pens bedded with woodchips and sawdust during the last trimester of gestation.

Researchers found cows in un-bedded pens were 82 pounds lighter and heifers were 96 pounds lighter than their counterparts in bedded pens.

“The loss in body weight corresponds to an increased energy demand of 3.9 and 4.3 megacalories per day, respectively,” Jaborek explains. “While the energy demands of a pregnant cow increase 6.5 megacalories per day from the initiation of gestation to calving, mud may increase these energy demands even further.”

Management and mitigation

“Managing mud can be a challenge,” states Jaborek, who suggests producers consider adopting management practices on their operations to allow cattle to escape muddy conditions.

Halfman notes, in addition to management strategies, pen maintenance and design; the use of bedding; proper drainage; preventing runoff water from entering pens; providing adequate space for each animal, especially in high-traffic areas such as around feedbunks and water troughs and moving cattle around to different areas are all ways producers can mitigate issues caused by mud accumulation this spring.

Hannah Bugas is the managing editor of the Wyoming Livestock Roundup. Send comments on this article to roundup@wylr.net.