6 minute read

Anti-racist Activism T rough Art and Facebook

— marharyta taraikevich

Special Text Edition: Daniel Jara

Advertisement

J.

When I immigrated to Belgium from Belarus, I quickly fell in love with its multicultural society. I was excited to work, to eat together and to communicate with people of such diverse backgrounds.

How to widespread this love? That was a question I asked to myself in 2015 when I felt my beloved multicultural and tolerant society under threat. That year I had the impression that the xenophobic discourse was rising, and I became motivated to challenge it by widespreading pro-inclusive narratives. I decided to do it by means of art.

I see my pro-diversity atitude as an undeserved gif. I have noticed that people who share anti-migrant views are often nice, kind and even tolerant in their practical life! So the question for me is: how to make the others see the beauty that I have the chance to see?

Searching For The Right Images

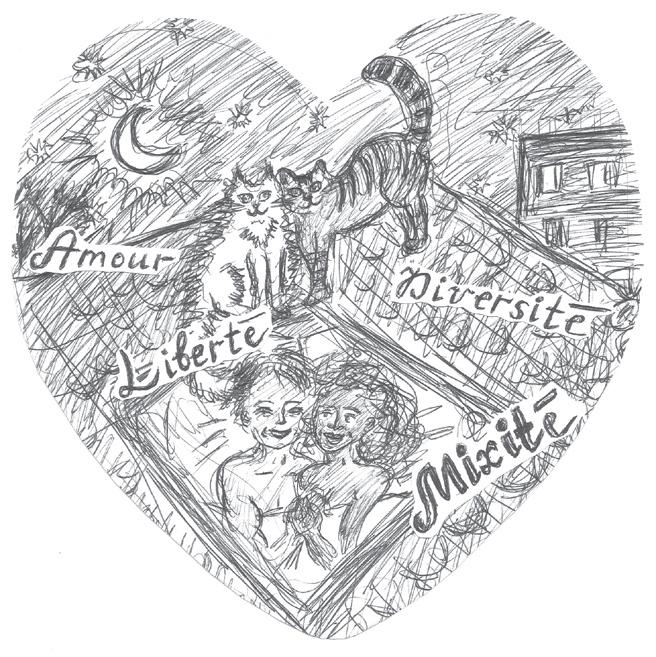

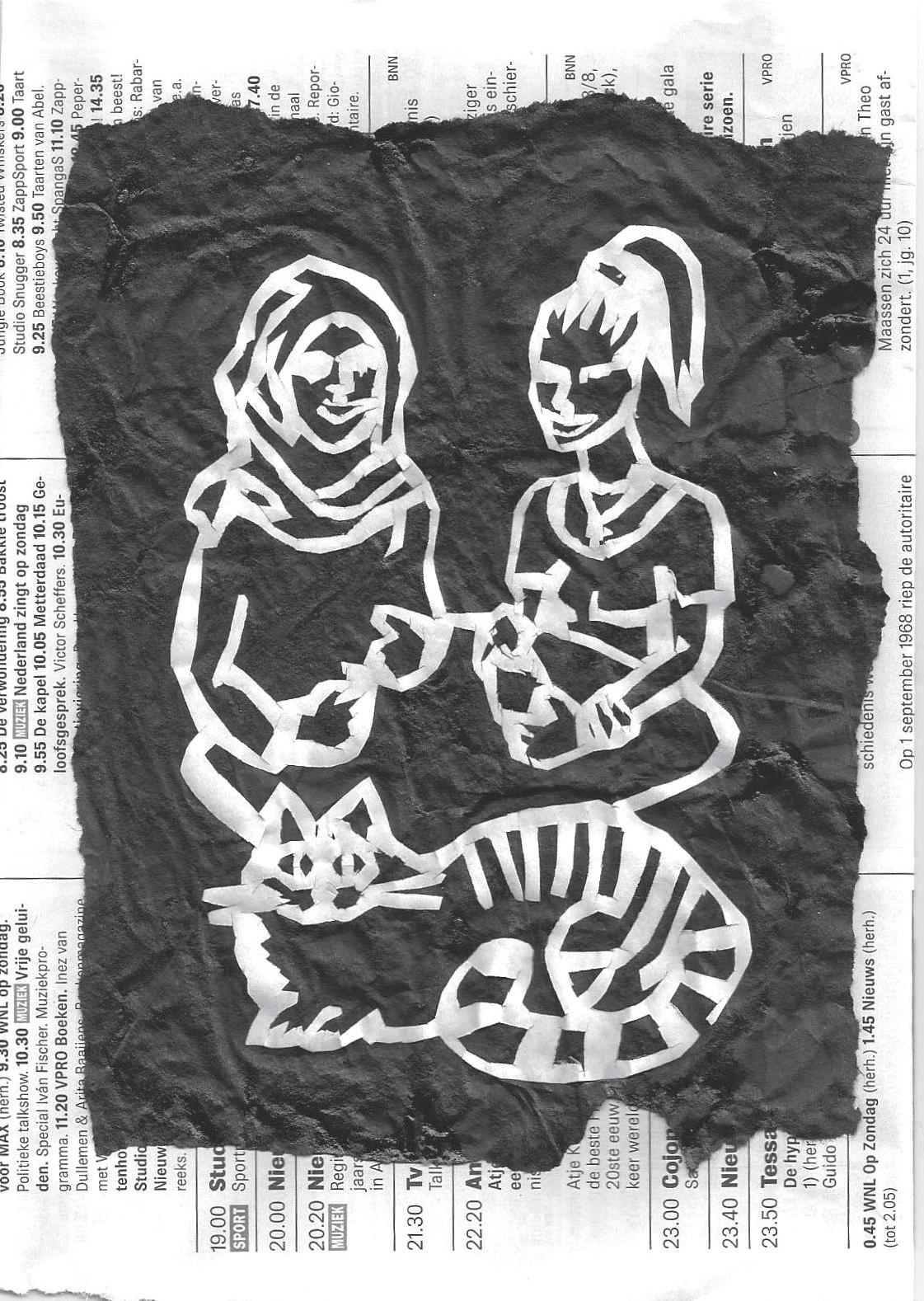

In developing visual images for pro-diversity propaganda, I’ve begun with works that may remind the soviet concept of the “friendship of peoples”. For example, the following image of two young women, one of whom is wearing a hijab may seem idealized. Nevertheless, it originates from my own experience: it represents me with a good friend of mine sharing a cofee. The cat is the only fictional character. On my perspective, it is important to remember that being optimistic does not mean being not realistic enough!

However, I must accept that it bears some stereotypes to overcome. Depicting a headscarf as an atribute of Islam is a bit narrow, inasmuch as not all practicing Muslim women consider its use as mandatory. On the other hand, many Christian women wear headscarves, for example, I put it on while entering an Orthodox Church in Belarus. So, in another paper-cuting work I depict a Muslim women with opened hair, and a Christian one wearing a headscarf, hoping it beter reflects how complex human diversity can be.

By that time I had already made my inspiring “migrant discovery”: I noticed that people’s views and values don’t directly depend on their ethnic origins, geographic backgrounds, or –strangely- religion. For me, the fact that sometimes I have more in common with a Chechen Muslim than with a Belarusian Orthodox Christian is a clear manifestation of our God-given free will.

In this sense, I believe that despite the great influence of one’s social context, we make our choices by ourselves. This is an additional argument against the “new racism” with its vision of diferent cultures as fundamentally incompatible.

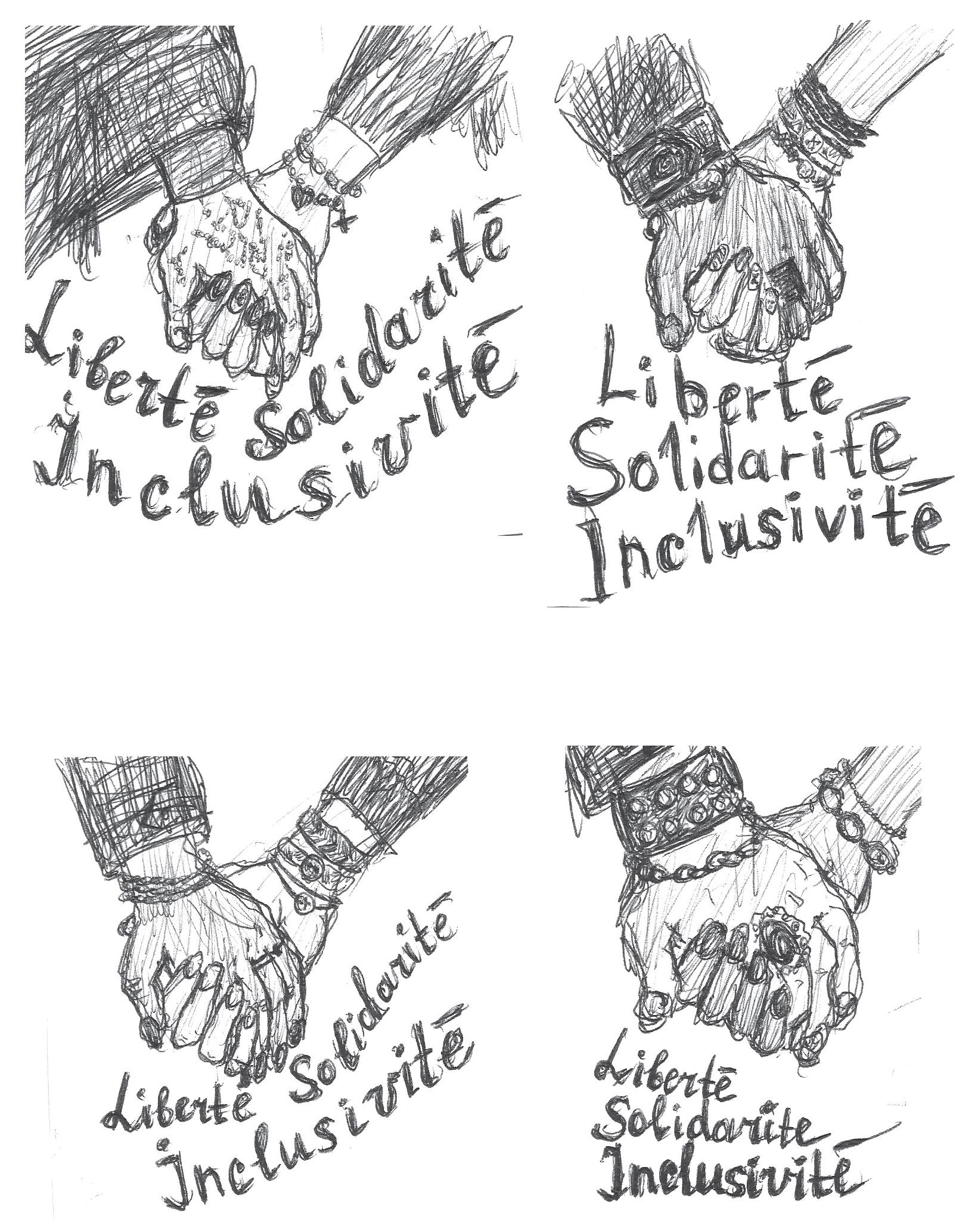

However, it poses a problem in visual art: how to represent a less visible part of diversity, such as views, values, choices, social and personal experiences? For me, it was an answer to depict this by showing hands, instead of faces.

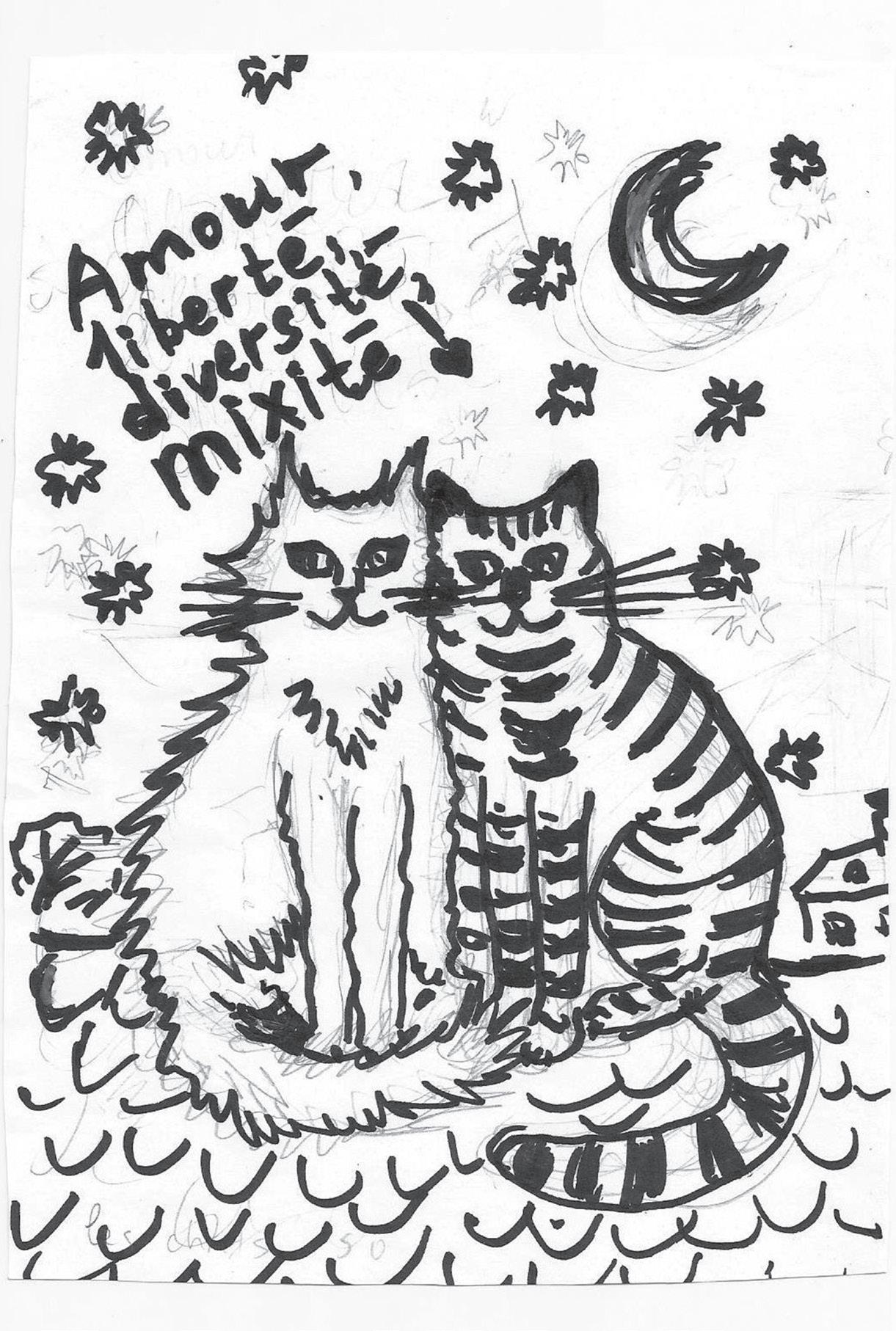

As an artist, I was constantly searching for the right symbols. For instance, I use cats as an anti-racist symbol because cats are always making multiracial love, constantly demonstrating that race mixture does not spoil the beauty of the specie.

In my work ships are symbols of migration. They show migration as an act of courage and hope. I don’t like seeing migrants just as victims: I prefer to underline their capacity to take risks.

However, I seriously doubt that they are optimistic symbols, considering that these means of transport are usually risky alternatives to safe and legal migration to Europe, and they are associated with deaths in the Mediterranean sea.

Connecting the image of a girl wearing a headscarf with the map of Europe is also a risky bet, as it may remind to some people the unfortunate concept of “islamization of Europe”. Nevertheless, I try to use it to challenge this narrative by representing a Muslim girl as part of Belgium’s diversity in the work “The girl from Brussels”.

Connecting With Others

In order to reach a broader audience, I passed from litle individual street art exhibitions and Facebook activism, to expose my works in empty shop windows (thanks to the artistic group ‘Vitrine Fraîche’ and its leader the artist Bere Zinc, who makes it possible in the town of Tournai). Since then we have been making grafti in collaboration with children and adults and with the permission of the local administration.

It did not take me long to understand the value of connecting my artistic vision and work with others who share the same interest and passion. For instance, it was exiting to discover how others invested their time making art with refugee children or building nets of solidarity with new-comers. But at first, I didn’t know anything about their actions. I managed to build connections with the activists only afer doing some actions myself!

During the last years, I have found some ways to use the works I had made solo to nourish collective actions and multiply their reach. For example, by participating in collective expositions.

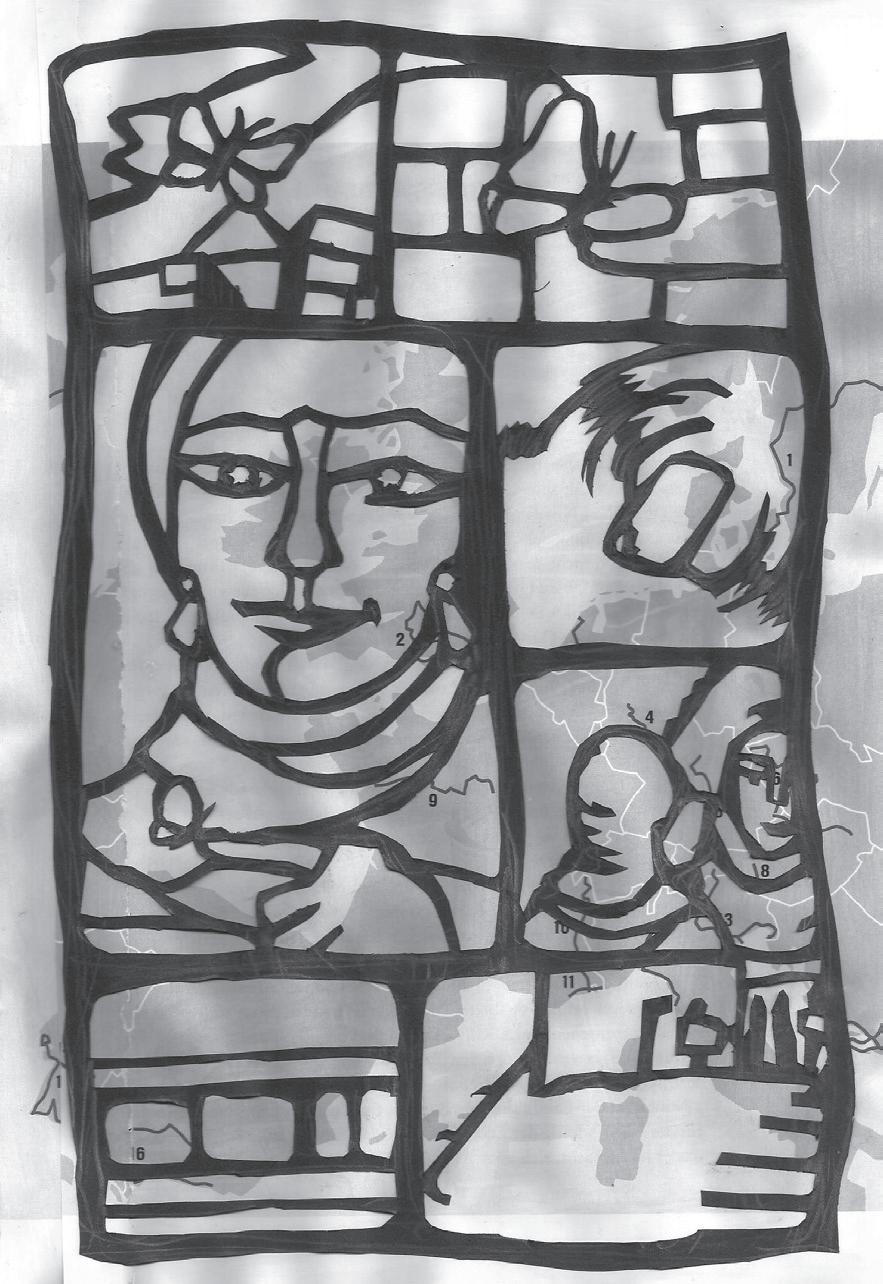

Love, Freedom, Diversity, Mixity! (2016; marker drawing)

According to some politologists only organizations or groups, not a one-unique person, can be considered agents of change. Nevertheless, I suppose we should not wait for finding an organization to begin to act, as it is possible to firstly work, and then to articulate eforts and experiences on collective endeavors.

For example, I am able to share my art and reflexions on human migrations in the post-ussr cultural spaces by online activism. It started by sharing my positive impressions about multicultural societies on my blog, the socio-political site “Belarussian Partisan”. Then I became active of Facebook, by widespeading pro-migrant posts and participating on discussions under friends’ texts. I also created a Facebook page mainly for French-speaking audience, where I post my pro-diversity art as well as links to articles and other information about migration and diversity.

Because I firstly used Facebook mainly for staying in contact with Belorussian friends and culture, once I wrote publications in French or in English, I just didn’t get “likes”, so I had no impression of being useful. Then I gained more Belgian friends, by deliberately adding people who share my views, and then, litle by litle, inviting them to like my page “Ouverture” (Openness). A decisive moment for my “Facebook activism” was when the Belgian government made it possible to confine families with children in centers for future deportations. Those who found unacceptable to imprison children put their profile pictures into barred frames. So I added people with such frames into my friends list, as well as those who used some other frames claiming solidarity with migrants. By doing this, I was able to energize my Facebook activism.

I also discovered that my anti-hate posts in French got more “likes” when they were accompanied by photos. That led me to publish pictures with short texts. I made them on PowerPoint afer installing it on my mobile phone. In this sense, I must admit I followed the example of the far right, with their viral memes on social networks. The diference was that this time I puted technology at the service of humanist ideas and verified information (for example, real numbers on immigration), with indicated sources.

I still consider my Facebook activities have limited influence, but it doesn’t bother me anymore because I recognize that it is also part of my activism to support the materials of others who share my same vision. Now I understand that even if I’m not strong enough to make great social changes just by myself, there is a special power of joint activism. I do it so on Facebook by “liking” anti-racist posts of others, by commenting them and by sharing their contributions.

Mistakes To Avoid

In the process of such propaganda, or social pedagogy, I’ve understood some mistakes of mine.

Firstly, I shouldn’t have denied someone’s right to be afraid, for example, of terrorism. Fear is valid. Even knowing that, contrary to myths, violent crime rate is now declining, so the world in general is becoming safer. Instead of shaming the others for their fears, we should admit that it is normal for people to want more safety.

Intersectional feminism taught me to listen to people, to believe them when they tell their own experiences. I shouldn’t have questioned people’s own experience, even if it is not convenient to me. For example, when they talk about unpleasant episodes with people of ethnic minorities. On the contrary, I must admit the complexity of social co-existence.

My own theoretical response to anti-migrant or anti-minority discourse consists of moral universalism, and intolerance to violence. I believe that both good and bad are universal, that objective truth exists, and that all of us can contribute to its collective search. I also believe that truth can be searched in common freedom, and that a feeling of freedom is an indicator of its presence.

I feel myself free in a society with strong social solidarity and tolerance to diferent kinds of otherness. I think that it is not only my subjective preference, but it is rooted in Christian love. I believe that this kind of freedom is real and good, and all kinds of oppressions are bad and must be fought and not tolerated anywhere in the world. “Tolerance to diference, intolerance to violence”, this is the slogan I use against misunderstandings on tolerance. It seems to be abstract, or idealist, but this kind of atitude makes my everyday life beter, it empowers me with social optimism, and helps me in discussions.

— marharyta taraikevich

Marharyta was born in Belarus (former USSR) and holds a Master degree in Social Pedagogy. She moved to Belgium in 2010, where she gained work experience organizing art activities. Marharyta is an Orthodox Christian, who is interested in the promotion of Belarussian culture, human migrations and diversity.

Tolerance to Diference, Intolerance to Violence (2018; drawing with a pen)