3 minute read

New York, Tchaikovsky'sThrough Eyes

from OnAir May 2023

by wkcrfm

by Alejandra Díaz-Pizarro

“51 years old. In the morning I was terribly worried about this day.”

So begins Tchaikovsky’s diary entry for May 7th, 1891, about halfway through his trip to New York City, where he had been invited to conduct at the inaugural concerts for Carnegie Hall—then still named quite simply the “Music Hall.” His arrival in the U.S. on April 26th was less than enthusiastic: a few days earlier, before crossing the Atlantic, he had read of his sister’s death in the newspaper, and only a large advance payment for his American tour had stopped him from canceling it altogether and returning to Russia. Nonetheless, the morning of May 7th, what Tchaikovsky was “terribly worried” about was not homesickness, or grieving, or aging. It was conducting.

The full first paragraph of the diary entry reads: “51 years old. In the morning I was terribly worried about this day. At 2 o'clock I had to conduct the concert with the suite [Suite No. 3]. This particular fear is a extraordinary thing. How many times have I conducted this self same suite! It goes splendidly; why am I afraid? And yet I suffer unbearably!”

Tchaikovsky was a prolific and devoted diary-keeper, and the entries for his New York trip—longer and more comprehensive than the average, with the thought that his family might later read them—offer a glimpse into the inner discourse of a deeply selfconscious man. Despite already enjoying the status of a beloved composer, Tchaikovsky was profoundly concerned with how he was perceived: the journal entry from the day before reveals a Tchaikovsky who, when reading the reviews of his conducting, reads them not for praise of his performance but fixates bitterly on their remarks on his older appearance and awkward demeanor.

“It makes me angry,” he writes, “that they not only write about music, but about me personally.”

Perhaps only a man that so agonized about being observed could’ve yielded as deeply observant a portrait of New York City as Tchaikovsky does in his journal entries. He comments on a Central Park that is freshly fifteen years old since its 1876 completion, hailing it as modern and commenting on its charms (”although the trees are still not all that old,” he adds, somewhat derisively). He marvels at the size of “the houses Down Town,” which “are gigantic to the point of absurdity; at any rate I refuse to understand how one could live on the 13th floor.” He puzzles over, and ultimately dismisses, a Socialist rally he stumbles upon. He delights in walking along Broadway, waxing about a walk that lasted “an hour-and-a-half! Such a walk might give one an idea of the length of Broadway. We walked for 1½ hours, and barely covered one third of this street!!!”

Tchaikovsky’s vision of New York, of course, rose above sightseeing: as a guest conductor for the opening of the foremost concert hall in America, Tchaikovsky was treated to every luxury that befitted a composer of his stature. Yet this luxury, which earns a few obligatory mentions in his journal, is not what appeals to him—in fact, he deems it “completely unnecessary.” No, what Tchaikovsky is enchanted by are the ordinary qualities of the people he meets.

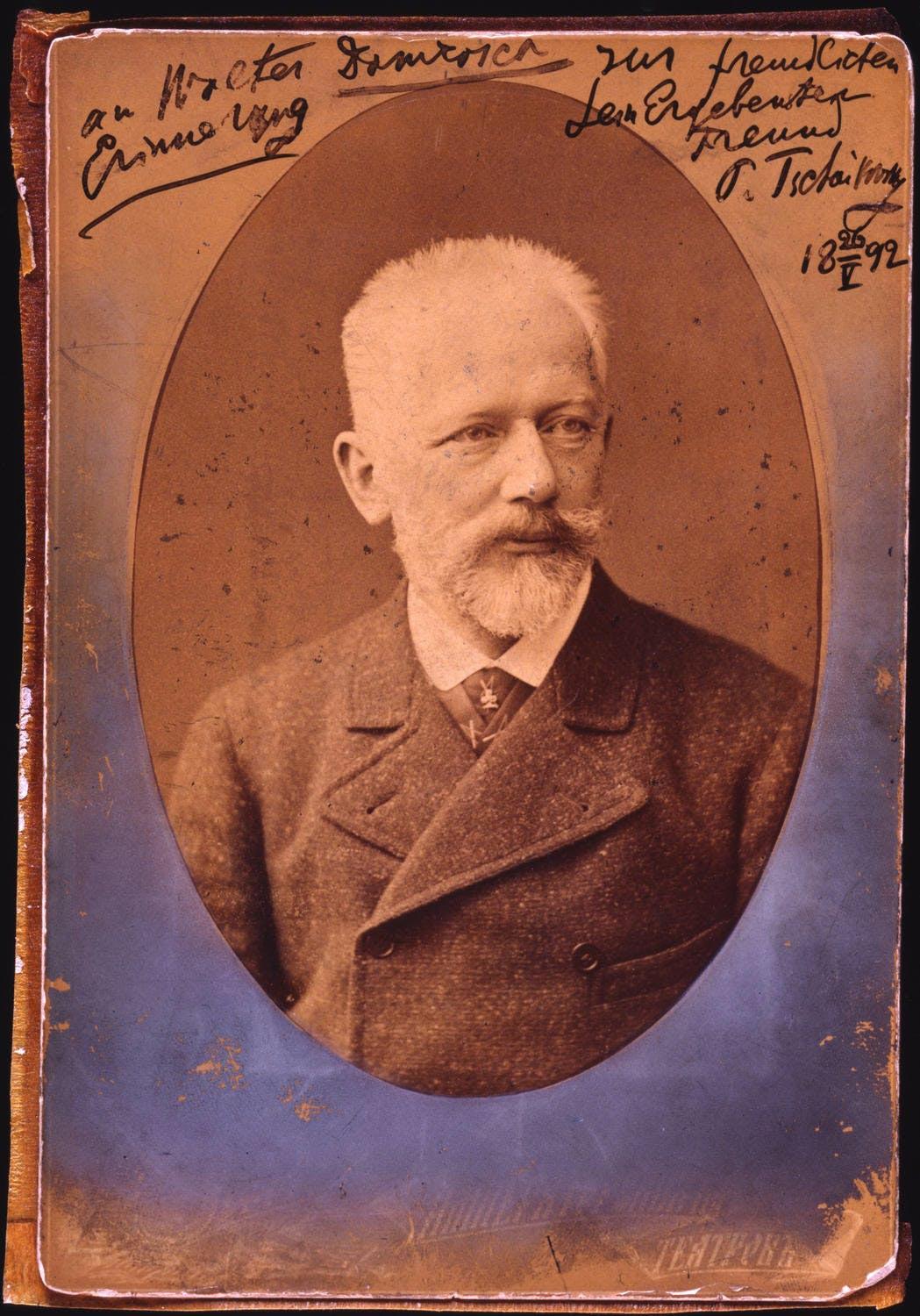

Though he moves in a sphere of high-profile characters, Tchaikovsky is disenchanted by social obligation and drawn not to names but to human qualities: composers like Damrosch and some of the crème de la crème of the New York music world (like Morris Reno, manager of the Music Hall, and William von Sachs, prominent critic & journalist) are cursorily named despite being Tchaikovsky’s regular escort party. Meanwhile, the young Russianborn hotel valet Max, who offers the composer one of the only tastes of his own language in an English-speaking land, appears and reappears with a telling tenderness in the journal’s recollections.

Perhaps the best illustration are Tchaikovsky’s encounters with Andrew Carnegie, the benefactor of the very hall Tchaikovsky has been invited to inaugurate. Despite this, he is plainly described as “little old Carnegie, the admirer of Moscow and owner of 40 million dollars,” and only once is Carnegie mentioned without Tchaikovsky amusedly remarking on his extraordinary resemblance to the Russian playwright Alexander Ostrovsky. Tchaikovsky’s most effusive comments on Carnegie, rather than be about his wealth, are that “he remains simple and modest, not turning up his nose at any man, and he strikes me as extraordinarily considerate, perhaps because of the way in which he has been so filled with kindness towards me.”

It is not just in his New York trip that Tchaikovsky appears as a man concerned with the minutiae of human life beyond the sheen of genius. His faithful diary-keeping was an attempt to stave off the fear that he might have lived even a single day only to forget it, and his devoted letters to his brother Modest and his friend (and patroness) Nadezhda von Meck reveal a man who deeply valued human connection. But it is when he is dropped in the middle of New York City, with its relentless hustle and bustle and its swirl of people-placesand-things and its booming urban character, that this side of him truly shines through.

Tchaikovsky returns to New York for his birthday this Sunday, May 7th, all day on the airwaves of WKCR-FM NY 89.9.

Thank you to Maria Shaughnessy for pointing me in the direction of Tchaikovsky’s New York journals. Full transcriptions of Tchaikovsky’s diaries are available at Tchaikovsky Research (tchaikovsky-research.net), both in the original Russian and translated into English.