4 minute read

Critical Step to Tokyo: THE BATTLE OF SAIPAN 15 June -

9 July 1944

In June 1944, the same month as Allied armies landed in France and fought their way up the Italian peninsula, on the other side of the world U.S. forces fought a critical series of battles on and around the Mariana Islands that contributed much to victory over Japan. The largest and arguably most important of these victories was the Battle of Saipan, which proved a key turning point in the Pacific War.

Advertisement

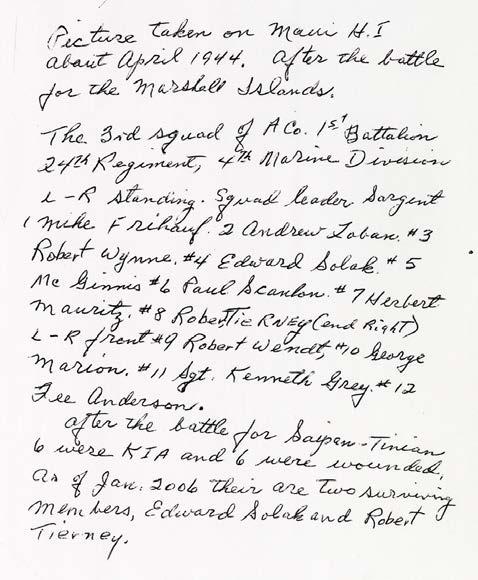

After Admiral Chester Nimitz’ Central Pacific forces captured the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, they turned their sights on the Marianas, 1,500 miles from Japan and a key part of Japan’s defense perimeter (known as the Absolute National Defense Zone) in the Pacific. The largest island in the chain was Saipan, and eliminating its 32,000-man garrison was the first critical step in breaking the Absolute National Defense Zone. This task fell to Major General Holland M. Smith’s V Amphibious Corps, comprised of 71,000 men in 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions and the Army’s 27th Infantry Division. Admiral Raymond Spruance’s U.S. Fifth Fleet covered the landing with the powerful Task Force 58, under Wisconsin-born Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher.

On June 15, the first Americans stormed ashore on Saipan’s southwest coast. Fierce Japanese counterattacks failed to dislodge the invaders. Offshore, the Japanese Navy sailed in an effort to crush the invasion fleet; in response, Spruance deployed Task Force 58 in a defensive position west of the Marianas. The resulting Battle of the Philippine Sea, June 19-20, saw over 550 Japanese aircraft destroyed against a loss of only 123 American planes. U.S. submarines and planes sank three Japanese carriers, while Japanese airstrikes slightly damaged a battleship. Mitscher’s sailors nicknamed their lopsided victory The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.

The Battle of the Philippine Sea did not stop the land fighting, as meanwhile Smith’s forces cleared most of southern Saipan and started north into the rugged mountains along the island’s center. The Japanese had dug in to the many caves in the area, each of which needed to be neutralized before the Americans could advance. For over a week the soldiers and Marines grappled with both the terrain and the enemy, with daily progess measured in hundreds of yards.

By early July the soldiers and Marines had captured most of Saipan, including the city of Garapan, the island’s capital. Victory was in sight as the 27th Infantry and 4th Marine Divisions pushed northward. On the morning of July 7, 4,000 Japanese, representing most of the remaining defenders and including civilians and walking wounded, launched a mass attack (called a Banzai charge) against the 27th’s 105th Infantry Regiment. The Japanese broke through in fierce fighting, but were wiped out by Marine reinforcements. Milwaukee-born Captain (Dr.) Ben Salomon earned the Medal of Honor for defending his hospital until death, one of three posthumous Medals of Honor awarded to men of the 105th. This was the largest Banzai charge of the Pacific War. The next day the 4th Marine Division pushed north against very light resistance. In the 4th Marine Division’s 24th Marine Regiment was

Corporal Robert Tierney of Chippewa Falls, who had already cheated death twice in the battle. At 4:30 P.M. on July 8 a radioman prematurely announced that the island was secured; 20 minutes later, a Japanese sniper shot Tierney in the back, seriously wounding him. (Tierney received his Purple Heart in hospital from Bob Hope, who was visiting at the time. This story is part of the Museum’s Every Veteran Is A Story online exhibit.)

As the Marines reached Marpi Point on the island’s northeast tip, they encountered most of Saipan’s remaining Japanese civilian population. These men, women, and children had been told to expect brutality at the hands of the Americans. Many took their own lives with guns or grenades, while about 1,000 jumped off the cliffs around Marpi Point into the sea. Marine pleas to stop were ignored. These suicides were among the estimated 22,000 Japanese civilians who died during the battle from all causes. On July 9, 1944, Saipan was officially declared secure.

Saipan’s Japanese defenders perished almost to a man; one of the dead was Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, who led the carrier forces at Pearl Harbor and the Battle of Midway and was senior naval officer in the Marianas. The V Amphibious Corps lost 14,000 casualties, or 20% of the attacking force.

The Battle of Saipan proved to be important in several respects. First, the American victory forever broke Japanese power in the middle Pacific. Saipan’s capture, along with Guam and Tinian, placed the Japanese home islands within range of B-29 bombers, a fact the U.S. Army Air Forces would exploit for the rest of the war. It was also the first battle involving many Japanese civilians, and the Marpi Point suicides forshadowed similar behavior on other islands in future battles. Lastly, Saipan was the largest Central Pacific and Marine Corps battle to date, demonstrating growing U.S. power.

The Japanese recognized what the American victory meant. “The war was lost,” stated Prince Naruhiko Higashiuni, commander of Japan’s home defenses, “when the Marianas were taken away from Japan.”

(Previous spread) Fighter plane contrails mark the sky over Task Force 58, during the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot,” 19 June 1944 Public Domain V Amphibious Corps insignia from the George W. Fox, Jr. collection. Fox served in the Marine Corps as a 1st lieutenant, Signal Battalion, V Amphibious Corps during World War II. V2007.21.9

I could see that beach. I saw Mt. Suribachi over on the left, and the billowing smoke and sand and stuff just rising hundreds of feet in the air… About that time I thought to myself what the hell am I doing here… The first thing, even before I hit the black sand, I saw three rows of dead Americans, dead Marines. That was my first view. My second view was the black sand… We hid in the first hole that we could, you know, guys spread out like they were taught to do and hid in the holes… The noise was relentless. You can’t imagine the noise unless you were there.

–Clayton Chipman, 4th Marine Division West Allis, Wisconsin

Istumbled into the museum field more than ten years ago as a history graduate looking for work, but I had no idea what it took to maintain and manage a professional institution. My first day on the job was an eye-opener. Administration, archives, collections, registrar, education, oral histories, leadership, and so many other departments coming together to function as a cohesive team focused on one goal: making our museum the best at what it does!

Last summer, the Wisconsin Veterans Museum had the opportunity to demonstrate to local