11 minute read

Saving The 'Food That Grows On Water' | DNR Partners With Tribes To Support Wild Rice

Emma Macek

Emma Macek is a public information officer in the DNR’s Office of Communications.

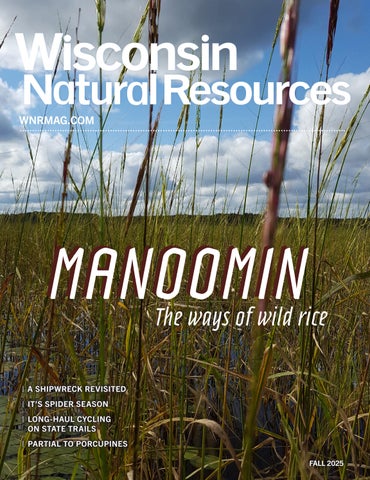

Wisconsin has incredible natural resources to enjoy, and for some of those resources, the cultural significance is undeniable. Wild rice, or “manoomin” in the Anishinaabe language, is one of them.

Found only in the upper Midwest and parts of Canada, wild rice was once abundant in northern Wisconsin and still serves a vital role in Indigenous culture and spirituality. But its presence in state waters has declined significantly over the past several decades.

“It's really kind of hard to picture what life would be like without wild rice because that's the very core of who we are,” said Kathleen Smith, a member of the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community. Smith is the Ganawandang manoomin, or “she who takes care of the rice,” for the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission.

GLIFWC’s most recent Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment listed manoomin as the most vulnerable species, ranging from “highly vulnerable” to “extremely vulnerable.” Highly vulnerable indicates abundance and/or range is likely to decrease significantly by 2050, while extremely vulnerable means abundance and/or range is extremely likely to substantially decrease by 2050 — or disappear altogether.

“It is tough knowing, especially hearing from elders, the struggles that wild rice has gone through, especially in the last few decades,” said Nathan Podany, tribal hydrologist with the Sokaogon Chippewa Community Mole Lake Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. “It was such a prevalent plant across the region.”

Learning why wild rice is declining and finding ways to stop that downturn is paramount to saving it. The DNR is collaborating with the Sokaogon Chippewa community, GLIFWC, UW-Madison Trout Lake Station and other tribes and partners to learn why wild rice is declining and help it grow better in a changing climate.

“If we don’t figure out how to counter this decline, we’ll lose an important Wisconsin resource, as well as the historical and cultural ties to it,” said Jason Fleener, DNR wetland habitat specialist.

Climate Threats

Wild rice is a resilient plant, but it’s also very sensitive and requires specific conditions to grow.

“All of the systems, plants and animals evolved under consistent weather, and as the weather gets more consistently abnormal, it's going to have an effect on wild rice,” Podany said. “And it’s not just rice; it's all habitat and all plants and animals.

“As we lose them, they’re harder to bring back and restore the wild rice water.”

With climate change, stronger and more frequent storms are affecting wild rice at every life stage,

especially during the floating leaf stage when the plant is most vulnerable. Intense storms and flooding can drown, damage or uproot the plant, and tribal members say precipitation makes it difficult to dry out the wild rice during processing.

Temperatures are increasing, too, negatively affecting wild rice pollination and seed production. The plant needs cold stratification — an overwintering hardening period of near-freezing temperatures — to promote seed germination in spring.

Increased temperatures also reduce ice cover in winter. This cover is needed to set back aquatic plants that compete against wild rice for space, such as water lilies and cattails.

Brown spot disease is also on the rise in wild rice due to temperature and humidity. Caused by a fungus, the disease can reduce seed production by up to 90%. It’s likely to become more prevalent with larger rain events and increased summer temperatures.

Other challenges include herbivory, which has become more problematic as increasing breeding

populations of geese and swans are putting additional grazing pressure on wild rice beds during vulnerable stages of growth. Plus, human land use changes such as dams, culverts and new roadways can alter hydrology and negatively affect wild rice.

Finding Solutions

Researchers are teaming up to learn what they can about wild rice to save it and help the cultural traditions live on.

“The more we learn about it, the better we are equipped to come up with strategies to manage and be the stewards of the resource,” Fleener said.

Much of the DNR’s research efforts involving wild rice are funded by a grant through the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s America the Beautiful Challenge. The DNR recently hired Cheyanne Koran, a member of the Menominee Nation, to oversee the grant and facilitate wild rice research projects.

Here’s a look at some of the ongoing work seeking to address specific issues facing wild rice.

Herbivory

DNR researchers are working with tribes, GLIFWC and other groups to study wild rice herbivory from waterfowl. Amy Shipley, DNR waterfowl and wetland research scientist, is leading a multi-year research project studying the impacts of herbivory on rice growth and seed production.

The study includes using 10-by-10-foot floating fences, called exclosures, on 26 waterbodies across northern Wisconsin, including at Spur Lake State Natural Area in Oneida County. The exclosures, constructed of plastic fencing on a PVC frame and supported with pool noodles, are placed in the water to keep waterfowl out of study plots.

The team measures rice characteristics inside and outside the plots to compare how the rice is doing in protected vs. unprotected areas.

Researchers are also collecting waterfowl fecal samples for diet analysis, conducting in-person bird surveys and monitoring trail cameras to determine what waterfowl species are present. Similar research is happening on the St. Louis River Estuary.

Vegetation

Different vegetation can affect wild rice growth, and scientists are learning how through a variety of research projects.

The DNR recently partnered with researchers at UW-Madison’s Trout Lake Station in northern Wisconsin to study rice growth. The team compared rice growth in three groups: successful populations; unsuccessful populations with declining harvestable rice; and populations that interacted with nonlocal, or invasive, species such as Eurasian watermilfoil and curly-leaf pondweed.

“We found some evidence that rice grains right at the surface without any protection are at a higher risk of being uprooted during the early growth season,” said Gretchen Gerrish, UW-Madison Trout Lake Station director. “If the grains were even an inch down or a couple of inches down into the muck, they had a better hold for their roots.”

In addition, the UW-Madison team is starting a new project studying how the roots of local vegetation, such as lily pads, affect wild rice growth.

These plants have large rhizomes, and as they naturally decay in the water, they release gases like methane and carbon dioxide. Those gases can then uplift the waterbody sediment where wild rice grows.

Researchers are trying to learn more about those chemical reactions to create a better habitat for the rice, especially in restoration areas.

At Spur Lake State Natural Area, a historically important wild rice water, researchers are creating a long-term record of the aquatic plant species found. Traveling by canoe, they follow a grid system, stopping at predetermined points. They then plunge a rake into the water, spin it around and pull it up to identify each species found on the rake.

They are trying to understand how removing competing vegetation, including lily pads and watershield, influences wild rice growth.

A couple of years ago, with support from the Natural Resources Foundation of Wisconsin and the Brico Fund, Podany and Carly Lapin, DNR

conservation biologist for Spur Lake, brought in a mechanical harvester to remove perennial floating aquatic plants in study plots.

The study includes a combination of cut vs. uncut and seeded vs. unseeded plots. Results show that seeding works well in both cut and uncut areas, with a little more success in cut areas.

Water

Research over the years has shown that wild rice grows best in water that is 12-24 inches deep, with 18 inches being the sweet spot. Teams are working to reduce water levels in lakes where the water is too high for rice to grow successfully.

This includes hydrology studies to determine what is creating the high water levels — such as culverts, roads or even beaver dams — and working to find solutions. Along with that, researchers are monitoring water temperature, chemistry and quality, including contaminants.

Other research focuses on the influence of groundwater on wild rice growth.

Traditional Knowledge

Even as scientific studies progress, researchers understand the importance of including the knowledge of wild rice that has been passed down through generations in the Ojibwe community.

Sagen Lily Quale, a member of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe, is a UW-Madison graduate student working with Gerrish at the Trout Lake Station. Quale is interviewing wild rice experts from the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and nontribal groups to learn how wild rice populations have changed over time.

“That tradition of passing down knowledge through voice and story is really important,” Quale said.

Fleener hopes continued research, collaborations and restoration efforts will feed into each other and sustain Wisconsin’s wild rice legacy for years to come.

“If our restoration efforts spark more people to care about wild rice, then we will continue to gain support to protect it,” he said.

In Awe Of The Wild Rice Ecosystem

There are two kinds of manoomin in Wisconsin. “Northern rice” (Zizania palustris) is harvested by people for food and found in lakes, rivers and flowages in northern Wisconsin. “Southern rice” (Zizania aquatica) is typically found in rivers in the southern part of the state. Since the seeds are smaller, it’s not usually harvested.

Wild rice creates its own “very unique ecosystem,” according to Scott Van Egeren, DNR water resources management specialist. He still remembers being amazed the first time he saw wild rice while canoeing on a lake in northern Wisconsin.

“It was like you were in a field, just surrounded by it, and it was the coolest ecosystem,” Van Egeren said. “It’s awe-inspiring to be in it when it’s that dense because it’s different than anything you’ve ever experienced as a biologist.”

Wild rice, one of the only aquatic plants that is an annual, provides a rich food source and habitat for wildlife, including waterfowl, blackbirds and muskrats. The plant is also known to be an indicator of good water quality and a healthy ecosystem.

‘Our Biggest Teacher’

This unique and productive ecosystem is part of why the Ojibwe people set up villages in areas where wild rice was found. Tribal ancestors were guided by “the prophecy” to migrate to the region to find manoomin, or the “food that grows on water.”

Another of Wisconsin’s tribes, the Menominee, also are closely tied to manoomin. Their name in Algonquin, “Omaeqnominniwuk,” means “wild rice people.” It was said that wild rice followed Menominee and would disappear when they left an area.

For tribes, the plant has been a key part of ceremonies, feasts and food security.

The traditions surrounding the wild rice harvest carry on all year and include researching areas beforehand and gathering needed materials, such as birch bark for the baskets and venison for the associated feast. Then, depending on the lake, rice is harvested around September.

“You’re out there connecting to the landscape and all the relatives that are around us,” said Kathleen Smith of the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission.

Smith, from the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, then chuckled, calling to mind the “manidoons” — “little spirits” or bugs — encountered while harvesting rice. Or the rice worms that bite.

“They’re always out there reminding us that we are still human.”

Tribes believe wild rice teaches many such lessons, Smith added.

“It’s not just a plant, but it’s also our biggest teacher, as manoomin is really important to our culture,” Smith said. “We believe that these lessons from manoomin teach us resilience, adaptation and relational accountability for us as humans.”

Learn More

You can be a good steward of wild rice by checking your waterway for the plant, taking steps to protect it and learning how to harvest it sustainably. Visit the DNR's Wild Rice Harvesting webpage or reach out to your local tribe.