4 minute read

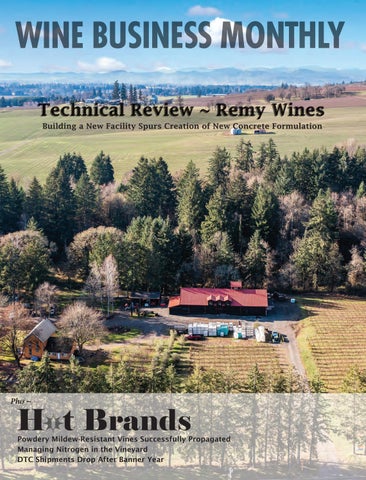

Technical Review ~ Remy Wines

The stairs to the second story are made with metal grating that was found on the property and welded together by students in a technical education class at local Dayton High School. The railings and banisters are made from old pallets.

Pallet wood also lines the walls of Drabkin’s office. She first got the idea for using it when she built out baR, a now-closed tasting room in McMinnville. At first, she was nervous to cover the walls with second-hand wood, she recalled. “But as we started picking out pieces of pallet wood, that’s when we noticed these pieces with ink, with numbering, with all these little details that were from the life of that product. They had all this beauty.” It speaks to the idea that “you have to be OK that not everything has to be perfect all the time. That’s part of finding beauty in the shadows, which is not hard to do.”

The centerpiece of her office’s décor is an old riddling rack mounted with custom metal braces. Before starting her own company, Drabkin worked at Argyle Winery, Oregon’s first sparkling wine house. During her brief tenure, Argyle was switching from traditional riddling racks to machines and sold some of the old wooden racks. “I bought this for $50,” she marveled.

The staff offices were built between the building’s original trusses, making them long and narrow. The builders added gables so the offices have plenty of natural light, which cuts down on energy costs and also makes for a more enjoyable work environment. Reclaimed doors salvaged from the property were hung to make barn-style rolling doors. The offices are lined with reclaimed wood that came from the garage demolition and another project.

The interior doors for the lab and other parts of the building were purchased at the non-profit ReBuilding Center in Portland. The sinks are almost all second hand. (The bathroom has a decorative sink made by Mead’s Vesuvian Forge.) The windows are new but have a high U-value, and the walls and ceilings contain around a foot of insulation. When the ductless heat pumps throughout the facility are turned on, it should maintain a fairly consistent temperature with minimal energy usage.

We can help.

Storage space in our brand spanking new South Napa building

29,000 square feet, ready for your full or empty barrels

Full-service solutions for your wine and beverage needs

• Bulk wine storage

• Bottling

• carbon dioxide that’s been sequestered is chemically released back into the atmosphere,” Mead said.

Heating the limestone and other ingredients takes a tremendous amount of energy, most of which is created by burning fossil fuels, so there’s a double whammy of emissions. For every pound of cement that’s produced, a pound of carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere. According to the Global Cement and Concrete Association, concrete alone produces 7 percent of the world’s total greenhouse gas emissions, making it the biggest carbon culprit in most construction projects.

Concrete companies know they have a big part to play in reducing the carbon footprint of their product, both for the long-term survival of human civilization and the short-term survival of their industry, said Michael Bernert, vice president and co-owner of Wilsonville Concrete and a major partner in creating the new concrete formulation. Holcim in Canada has already developed several products, including OneCem and NewCem Plus, that have significantly shrunk the emissions associated with making concrete. But there’s only so much any technology can do to because breaking apart virgin limestone and heating it to high temperatures is always going to cause enormous carbon emissions. Concrete is one of many products that must look to net carbon emissions—finding ways to sequester or trap more carbon in the built environment than they release into the atmosphere—as the solution to the environmental damage it causes.

One way to do that is to mix in biochar, which the International Biochar Initiative defines as “a solid material obtained from the carbonization theremochemical conversion of biomass in an oxygen-limited environment.” Biomass is organic waste that often comes from things like agricultural and forestry waste, yard clippings and food scraps. If these carbon-rich items are left laying out in places like fields, forests and landfills, they slowly decompose and emit gases such as carbon dioxide and methane—a gas that has a warming capacity 80 times higher than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period.

To avoid these emissions, this organic matter needs to be removed from the carbon cycle. That’s where biochar comes in. When organic waste is pyrolyzed (burned at a very high temperature in an oxygen-starved environment), most of the volatile compounds that would cause it to offgas are burned off. What remains is the energy created from the burning (enough to carry out the

General contractor Mead estimates the cost for all the sustainability features made the project about 1.5 percent more expensive than it might have been otherwise. The fact that Drabkin preserved so much of the original structure helped cut down on overall expenses. Recycling materials, such as metal and wood, lowered disposal costs. Those cost savings made it possible to include slightly more spendy features such as the high-efficiency windows and added insulation. Noting that 1.5 percent is the amount someone might spend on high-end countertops or appliances, he called green construction “totally accessible.”

To help Drabkin fulfill her goals around worker safety and increased efficiency, the facility has numerous utility hookups scattered throughout the winemaking area. Instead of wheeling around tanks of CO2 and nitrogen on hand trucks or running long hoses for hot and cold water, employees can attach lines to these hookups and get access to most of the things they need.

Drabkin is particularly proud of her “equity bathroom,” which has multiple stalls, is ADA compliant and is accessible from both the interior and exterior of the building. When harvest crews come to work, they will have full access to the facilities instead of relying on portable toilets. “This is a basic human function. We should all be able to wash our hands,” said Drabkin.

Carbon Neutral Concrete

When Mead committed to working with Drabkin on the winery project, he also asked if she would be willing to try out a new concrete formulation that included biochar. He had been experimenting with biochar in concrete for products such as his countertops and fireplaces, but his formulation wasn’t strong enough for structural uses.

Developing a carbon-neutral or carbon-negative concrete, he knew, had the potential to revolutionize the industry and construction as a whole. Concrete is made with a mixture of sand, gravel and cement. Cement is responsible for binding the mixture together, and the main ingredient in cement is calcium carbonate, which comes from natural deposits of limestone. The shells of the fossilized sea creatures that make up the limestone have absorbed and trapped carbon for centuries. However, “when the limestone is baked at 2,500° F, the