6 minute read

Finding Magic and Your Voice

Timbre Cellars 2019 Lead Vocals

Like many college students, Joshua Klapper worked in restaurants when not in class at the University of Southern California. Unlike others, however, he worked on the sommelier team at Sona, an establishment that had just received a grand award from Wine Spectator for its wine list. Because of the tasting opportunities this afforded, Klapper knew that he wanted to do more in the wine business and looked to other sommeliers, like Michael Bonaccorsi, MS, for inspiration.

“I just felt like I wanted to explore something different,” he said. “An easy jump at the time was to start making a little wine.” Klapper then followed in the footsteps of other Los Angeles-based sommeliers branching out into enology.

He reached out to some well-connected friends in the industry to purchase grapes and, with the help of another winemaker, began making blends in 2004 out of his garage. When he graduated in 2006, he had already spent years visiting wineries in the Central Coast, bottling his own wines, and knew that restaurant work, while fulfilling, was not the way forward.

“I decided to take a sabbatical from the restaurant business and worked my first harvest. That was when I fell in love, and I realized I wasn’t just going to buy juice from other people or have other people make my stuff. I wanted to be the chef,” he said. “I was 26, I’d been working 60 hours a week in restaurants, going to school full-time, working really hard. I was like, ‘If I work hard doing anything for myself, at least I’ll be in control of my own destiny. It may take me longer to make money or be successful, but I’ll ultimately be happier.’”

Klapper knew from the outset that he wanted to make Burgundian-style wines—those with lower alcohol—and chose Santa Barbara County as his home, thinking that would be the easiest place to do so. Following a conversation with some of the best winemakers of the Central Coast, he concluded that only Burgundy can be Burgundy, no matter the alcohol level. This realization about terroir led him to instead seek out sites where “magic happened”.

“I can’t exactly put my finger on what it is, but I know that the wines are exciting from those places,” he said. “I like making wines that are generally interesting, that have tension, that have that balance of acidity, richness, deliciousness and complexity, but I don’t like interesting for interesting’s sake. Interesting has to be delicious.”

For something to be nteresting it must also have character—whether it’s a sense of place or sound. In 2012 Klapper named his brand Timbre, which means the character of sound, or what makes our voices sound different. “Five hundred decisions are made for even a pedestrian wine. When you make it a fine wine, maybe it’s even more decisions,” he said. “All those decisions as a winemaker add up to your voice.” This is the idea behind Timbre.

Leaning into this theme, each wine has a musical term as its name. Klapper thinks of the 2019 Lead Vocals like Mick Jagger or Madonna—someone who is iconic not just for their voice, but for their personality as well.

“That’s how we’ve always thought about Bien Nacido Vineyard. Lead Vocals came from own-rooted vines that were planted in 1973,” he explained. “Finding own-rooted Pinot Noir is very rare. It was just this unique thing because it is so old, and it has a unique expression.”

The 2019 vintage, however, was the last from these old vines, as the block was torn out and replanted for the next vintage. This last bottling is a special one for him.

“You’ll never see a sale on that wine at my winery, or any of the Lead Vocals wines I made over the years—just like you wouldn’t see a sale on RomaneConti. It’s a special place and time in a bottle.”

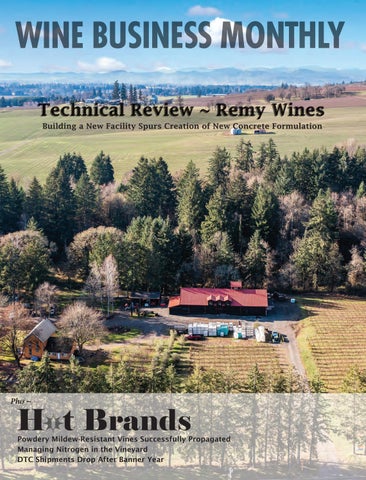

Technical Review ~ Remy Wines

For 12 years, Remy Drabkin, owner and winemaker at Remy Wines, made all of her wine in a rented facility in McMinnville, Oregon. When her landlords informed her in 2021 that they would not renew her lease for the 2022 harvest, she was left with a difficult decision. Should she scramble to find a new place to rent? Or should she finally move forward with her long-held intention of converting an old barn on her property into a winery?

Drabkin opted for the latter, even though she had only a year to get the project done. But Drabkin, who is also the mayor of McMinnville and the co-founder of Wine Country Pride, is no stranger to overcoming challenges and mobilizing people to make things happen. She quickly built a team to meet the goal of having a functional winery in place by September 2022. In the process, she also helped spur the creation of a new concrete formulation (dubbed the Drabkin-Mead Formulation) that is billed as carbon negative—making it possible to transform one of the most potent greenhouse-gas-emitting products in construction into a carbon sink.

A Winery Decades in the Making

Drabkin’s mother was the first culinary director of the International Pinot Noir Festival and stayed in that position for 15 years. Many of her parents’ friends were winemakers. Given that, it’s perhaps not surprising that Drabkin began telling people she planned to be a winemaker when she was only 6 years old. Her dream was helped along by her parents’ purchase of a 29-acre property in the Dundee Hills AVA in the mid-1990s. Though they had no intention of making wines themselves, they understood the property, which has patches of Jory soil and is located near big names like Sokol Blosser and Archery Summit, was a good investment. Drabkin suspects they were already thinking about her future and believed the property was an investment in her as well.

However, making the property habitable kind took a tremendous amount of work. It had been abandoned and in foreclosure for several years. Everything was overgrown with blackberries. There was an antique apple orchard that had to be taken out. (Some trees were so fragile that if you picked an apple, the whole tree often fell over, Drabkin recalled.) The site had also been used as a dumping ground. “We pulled something like 30 tractor tires off the property,” she said, along with railroad ties and numerous other bits of detritus.

Slowly, the family unearthed the property and the 1900s-era house, which they then both lived in and rented. Drabkin made some of her first wines in it, and the home currently serves as Remy Wines’ tasting room. The building didn’t have enough room for a full-scale winery, which is what led Drabkin to her warehouse in McMinnville.

Building and Outfitting the Winery

The property outside of McMinnville also had an open-sided garage that was built around 1940. In the 1960s, a pole barn was constructed over the top. Drabkin’s long-term plan was to build a winery there—a goal that became a necessity in 2021.

Drabkin had known John Mead, a local contractor and owner of a concrete surfaces company called Vesuvian Forge, for years and has always loved his aesthetic. He had also walked the property and discussed the project previously, so he was the first person Drabkin called about the potential winery project. He was confident he could make the project happen in the timeline and began pulling a full team together.

As she thought about out her goals for the winery, Drabkin was clear that she wanted functionality and the ability to improve her winemaking process. She also wanted to focus on sustainability, but “sustainability is not just environmental,” she said. “It’s about workplace safety, workplace happiness, and equity and diversity. It’s about getting out of small pockets of culture and being really intentional about being cross-cultural. It ties in with how I live my life and try to build a community that lets people thrive.”

While the building has several notable features that make it welcoming, the environmental sustainability features are the ones that are most readily apparent when looking at the 5,000-square-foot facility. The winery is made with the principle of adaptive reuse in mind, meaning much of the building features many salvaged and second-hand materials.

Rather than tearing down the existing barn, the construction team saved as much of the existing structure as possible. In addition to adding exterior walls, they build a second story on existing load-bearing walls inside and reinforced the existing trusses by sandwiching them between new trusses. That made the roof strong enough to hold a water collection system to feed the fire suppression pond and support the future installation of solar panels if Drabkin chooses.

When possible, materials from the original structure that were removed found homes elsewhere. A pair of pillars that used to be in the main structure were put to use holding up an outdoor utility porch. Large pieces of concrete were repurposed into a bench.