8 minute read

broadband

native plants, now known as the Arleta Triangle. She often cites the project as evidence of her ability to bring disparate parties together to overcome challenges.

Advertisement

Iannarone’s community focus won over her highest-profile backer, state Rep. Karin Power (D-Milwaukie), chair of the Oregon House Energy and Environment Committee.

In January 2018, when an ice storm gripped Portland, Iannarone helped set up an emergency warming center near Interstate 205 and Foster. Power responded to Iannarone’s call for supplies, filling the back of her Prius at Costco.

“She puts in the work and she shows up,” Power says. “That’s the kind of thing that makes us all think, ‘I should take the road a little less comfortable and do more.’”

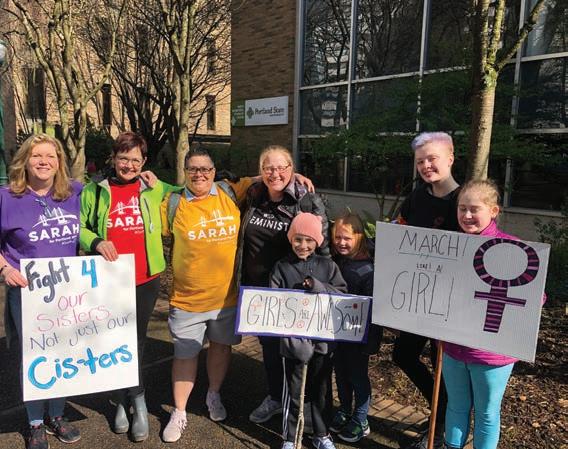

COMMUNITY BUILDER: “I am deeply rooted in the community, so I won’t need to be taught how to listen to the demands of the public or how to work through coalition to get things done,” Iannarone says.

IANNARONE IS LESS THAN TRANSPARENT ABOUT HER ACADEMIC CREDENTIALS.

Her characterization of her academic bona fides is a recurring issue. In the 2016 Voters’ Pamphlet, Iannarone described her educational background as “PhDc”—the “c” standing for candidate.

In May 2020, she changed that description to “Ph.D. (ABD)”—which means “all but dissertation.” She’s repeated that phrasing in the November Voters’ Pamphlet.

In other words, Iannarone purports to have earned a doctoral degree she’s been working on since 2006, except for completing her thesis.

Under Oregon law, making a false statement in the Voters’ Pamphlet is a felony.

“An example of a false statement under ORS 260.715(1) is stating the candidate has a college degree when the candidate does not,” the elections manual says.

“She’s absolutely violating the spirit of the law,” says Jim Moore, a professor of political science at Pacific University (and a Ph.D.). “That ‘c’ or ‘ABD’ doesn’t mean anything in academic nomenclature. She doesn’t have the degree. It’s that simple.”

Iannarone defends the characterization. “It’s actually a set of qualifications that I’ve accomplished,” she says. “I am ABD and I have advanced a candidacy in a Ph.D. program. So that’s actually accurate.” (PSU professor Carl Abbott, Iannarone’s Ph.D. adviser, declined to comment.)

6. HER COMMUNICATION IS UNFILTERED. Iannarone’s Twitter account, @sarahforpdx, has 18,400 followers. That’s a quarter of Wheeler’s following, but Iannarone’s posts are far more memorable.

Wheeler’s posts have a Dudley Do-Right quality, which makes him an easy target for mockery and scorn. By contrast, Iannarone does the targeting. Throughout the year, she has used her social media presence to decry the city’s police and its mayor.

“I’m publicly financed. Ted is bought and paid for,” she tweeted Aug. 9. “I’m a progressive grounded in community. Ted is a neoliberal grounded in finance.”

And on Sept. 4: “Wheeler has dug into refusing to address the true threats to our city: a rogue police force with sympathies for white nationalists.”

Between 2016 and today, Iannarone traded in the pearls she wore in her first campaign for a gas mask. On dozens of nights over the past three months, she joined protesters outside the Mark O. Hatfield U.S. Courthouse.

In an Aug. 7 interview on KGW’s Straight Talk, Iannarone repeatedly declined host Laural Porter’s invitation to disavow property destruction at the nightly protests.

“Peaceful protests, in my opinion, might not necessarily be moving the conversation forward,” she told Porter.

Iannarone says Porter didn’t give her a chance to fully answer the question. The day after taping the show, she sent KGW a statement. “Criminal activity is illegal, and of course I don’t condone it,” she said in her follow-up. “What I’m focused on is ensuring police do not use violence and even lethal force against people who have done nothing wrong.”

But John Horvick, a pollster at DHM Research, says he isn’t sure Iannarone’s public pronouncements resonate with most voters.

“I think the average voter in Portland would find her unappealing,” Horvick says. “That voter not as liberal as Iannarone or her Twitter feed seems to think.”

Iannarone acknowledges she’s more outspoken than she was four years ago. She says there are two reasons for that.

First, she doesn’t have to worry about offending contributors.

In 2016, she fell far short of her fundraising goals. Since then, she helped shaped the city’s new public campaign finance program and is its biggest beneficiary, scoring the maximum allowable $304,000 in city matching funds in the May primary. She is well on her way to maxing out for the general election, as well.

Wheeler, who previously financed his campaign with big checks from real estate developers and business leaders, bet campaign finance limits approved by voters in 2018 would get stalled in court.

He got that wrong and his campaign has failed to generate donations. (Iannarone has raised $471,000 in 2020, nearly twice Wheeler’s $258,000 total.)

The second big change: This time Iannarone is running against an incumbent with a track record instead of for an open seat.

“The last four years under Wheeler have made me a more vocal activist than even I would’ve liked to be,” she says, “because I’ve had to fight against policies that I think would harm my community.”

Observers who have worked with Iannarone say she has a temper. Two examples involve the Arleta Triangle.

Walt Nichols, a former chairman of the Mt. Scott-Arleta Neighborhood Association, clashed with Iannarone when he raised questions about the project’s finances. “It’s her way or no way and there’s no middle ground,” he says. “She is caustic and she takes things really personally when challenged.”

Iannarone rejects that criticism: “Walt never volunteered, helped or wanted to be involved in any way except in telling us what to do and making demands of those of us doing the work,” she says. “I have zero tolerance for lazy blowhards and, of course, pushed back.”

Nichols notes that fallout from the project also led to another incident that demonstrates Iannarone’s temper.

Iannarone and Brian Borrello, an artist on the Triangle project, sought restraining orders against each other in 2010. In court documents, Borrello accused Iannarone of spray-painting an image of “an ejaculating male penis with the words ‘loose cannon’ on my workplace door.”

Iannarone and Borrello declined to comment on the allegation, but Lakeman of City Repair recalls the dispute.

GRASS ROOTS: Iannarone, in the pith helmet she wears to protests (top), has received money from 5,000 contributors.

He says although Borrello is his friend, he can be a hothead. “I’ve called him a dick myself,” Lakeman says. “She just went a little further.”

DESPITE WHEELER’S UNPOPULARITY, IANNARONE HAS STRUGGLED TO WIN OVER KEY ALLIES.

Iannarone is running to Wheeler’s left. Yet she is not picking up some of the key endorsements she might have hoped to earn. Despite her aggressive climate plan, for instance, the Oregon League of Conservation Voters, the state’s largest environmental group, recently endorsed Wheeler. OLCV board chair Jules Bailey (who ran against her and Wheeler in 2016) says that’s because Wheeler accomplished diffi cult tasks. He cites the residential infill project, which the City Council passed Aug. 12 after a five-year battle with neighborhood associations and other opponents. “It’s easy for somebody to stand up and say, ‘I’ve got a plan,’” Bailey says. “It’s another thing to stand up to powerful neighborhood and entrenched interests. Wheeler took a political risk in doing that.” On Sept. 14, the Next Up Action Fund, the voter engagement group formerly known as the Bus Project, endorsed write-in candidate Teressa Raiford for mayor. That was a repudiation of Iannarone, who got more than twice as many votes as Raiford in the primary. In a lengthy explanation of its decision, Next Up called Raiford “the fi ghter we need as Portland mayor to tackle the issues of police brutality, the climate crisis, houselessness, renter’s rights, and equity pay for living wages.” All things, of course, that Iannarone has pledged to do. Two fi gures central to the past three months of racial justice debate also aren’t convinced Iannarone is the answer. State Sen. Lew Frederick (D-Portland) has led the push for police accountability measures in Salem. He’s known Iannarone for nearly 20 years, much of that time as a fellow PSU grad student. He endorses Wheeler. “She’s a great person and has a lot of good ideas, but I think she’d be better in another role,” Frederick says. “I may disagree with Ted on how he’s handled police issues, but I still feel he has a better handle on how to manage the whole city.” The skeptic who could prove most costly to Iannarone is Jo Ann Hardesty, the city commissioner who holds considerable sway with the electorate—as she demonstrated by helping Dan Ryan defeat Loretta Smith in the Aug. 11 special election runoff for City Council. Hardesty might seem the most sympathetic ear for Iannarone’s criticism of the police and Wheeler’s management of the bureau. Iannarone even co-authored a March 12, 2019, op-ed in the Portland Tribune urging that the mayor put Hardesty in charge of the Police Bureau, an assignment she’s pushed for ever since. Hardesty endorsed Wheeler in the primary. She says she remains undecided whether she’ll endorse him in November—yet she’s not inclined to endorse Iannarone. “She’s a nice woman and she has some good ideas,” Hardesty says. “But with the current crises, can Portland really afford another one-term mayor?” Intern Hank Sanders contributed reporting to this story.

STILL HERE: Mayor Ted Wheeler is taking heat from all sides, including the women pictured above and below him on this page.

STATE OF EMERGENCY

Photos by Alex Wittwer On Instagram: @_wittwer

As wildfires burned across the state, thousands of Oregonians were forced to flee their homes—while others fought the flames.

On this page: Evacuees gather in Clackamas County.