9 minute read

Women Shaping Conservation – Tiffany Bader

t’s -23 C, and I’ve been sitting on a small insulated pad for hours now, wrapped in my camouflage, making no sound, not moving and trying not to get frostbite. I see an animal in the distance... no I see two. In a heartbeat my binoculars are in my hand and I confirm two whitetail does, 400 metres away. They are slowing their walk through the bush, bending to eat the bits of vegetation popping up through the snow. They seem to be oblivious to my presence or, more likely, they realize they are safe because I’m looking for a buck.

I’ve been in this situation forty times or more, but my heart still quickens when an animal emerges into view, seemingly from nowhere. Does this reaction ever fade, or is it some mental management process to keep me from going into fullon buck fever? I lose my sense of stillness... Will I be ready when the buck comes around, will my hands work, or will they be too cold and numb? Will I be able to adopt a stable shooting position and make an ethical shot, or will the opportunity slip away? I have to steady my nerves, so I try box breathing, a mindfulness technique used by the special forces, carefully visualizing every action required for a successful outcome, step by step. You may wonder how a girl from the urban sprawl of Vancouver where firearms are taboo, ended up here, head to toe in camouflage holding a Sako 85 surrounded by the wild. I wasn’t born into a lifestyle that celebrates Type 2 fun. Hunting formed no part of my family’s culture. My experiences prior to this would be better classified as “in search of comfort.” Testing my physical and mental boundaries wasn’t something I routinely put myself through, assuming team sports like soccer and field hockey don’t qualify. Coming into my twenties I started to find life boring and unfulfilling. I tried to remedy this disconnected emptiness in my life through hiking and gardening, anything to reconnect with the natural world and gain a better understanding of myself, of my capabilities. I had always loved the outdoors and had learned a respect for analytically quantifying our impact, both positive and negative, when working with my father in forestry research at UBC. After graduating university and working several well-paying, respectable jobs, I found myself disheartened, unmotivated and with no north star or purpose. It was quite the leap of faith when my boyfriend (now husband) urged me to quit my lucrative office job and explore what it was that truly brought me happiness. I thought long and hard and eventually came down to these core questions that I needed to answer for myself:

● Am I challenging myself, learning new skills, and growing in a way that would make the future me proud? ● Are these skills I’m developing proficiency in going to result in a positive change, not only for me but for others around me? ● Will my short existence on this planet be of any significance?

The times in my life I have felt the happiest and most fulfilled were when the work I did benefitted others. I learned acting in the service of others has been scientifically proven to make you less susceptible to stress, leads to increased levels of life satisfaction, and staves off disease. I needed work I’d be proud to do, to be of service to others. I have always loved food—the cooking, eating, procuring ingredients, the sharing of it all. As a child, my large family came together to share a meal and stories and that slowed the rhythm of life, connected us with each other. It was during those meals that I learned to serve others, learned to listen, learned about my culture so it was not a leap for me to focus on food in some way as my potential career path. I enjoy cooking, creating meals, finding ways to create dishes to highlight ingredients, and bringing people together. Food sustains us, transforms us. That gratifying, satiating feeling that is deeply rooted in human history, derived from how we communicate our love and intentions through food, called to me. “You want to do what?” my close friend said. “You realize there isn’t any money in that.” I knew, and I didn’t care. I wanted to be a chef. I started at the bottom, working at a well-known BC restaurant chain, learning the craft. At the same time, I was working as a stagiaire in an unpaid kitchen internship at one of Canada’s top restaurants and spending my weekends in a bakery. Years of this led to some extraordinary opportunities in fine dining and a number of awards. Despite what the naysayers told me, I concentrated on providing the best to customers and learned success is a natural by-product of hard work and passion. As a chef, I was always interested in where my ingredients came from. If I’m going to roast a chicken, one raised in a pasture, free to run around and eat bugs, will taste infinitely better than a poor bird that’s spent its eight short weeks of life stuffed in a cage. A wild salmon is a different sea creature than one grown in a pond and fed food dye so its soft flesh mimics its wild counterpart’s. Around this time, the 100-mile diet was becoming increasingly popular,

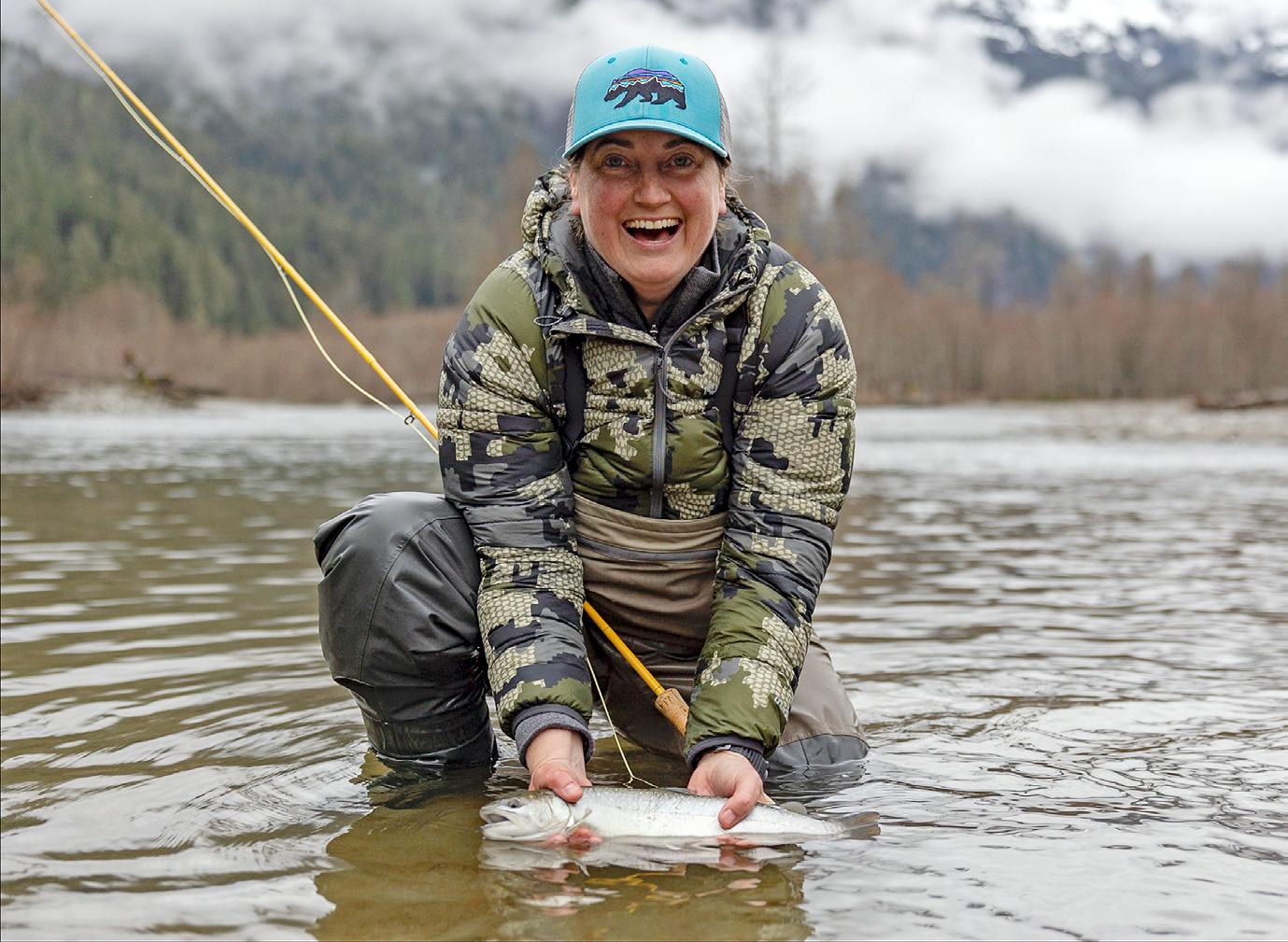

as was the desire to eat more organic food, which all played a part in my developing values on food and cooking, driving my passion for using local and unprocessed foods. I saw the good, bad, and ugly of our food system, and like many chefs of my generation, I started putting in the time to source foraged and wild foods, and this bled into my personal life. I spent a ridiculous number of hours reading about foraging and plant identification, and more hiking in the woods, putting that research to work, foraging on my own in earnest, recording my secret spots on maps and on my calendar, so I could remember where I found that hidden nettle patch next spring. I’d start paying attention to the weather, the temperature, how much precipitation we were getting to determine if we’d have a late mushroom season or if I should head out to the woods to have a poke around. And although I’d known this before, back when I’d done forestry work with my father, I now lived and breathed these connections in nature—the symbiotic relationships that cause mushrooms to grow only under certain trees at a certain time of year with just the right weather conditions. I was no longer willfully ignorant or blind to the beauty of nature. I started hunting with my husband, initially to spend more time with him doing something he loved, but it also gave me greater control over what I fed my family, allowing me to connect more with food and nature. To have the buck stop with you, to make the decision to take another animal’s life is significant and, unfortunately, far less common than it once was. It has truly altered my perspective of life and death and the responsibility of it all after that. Every decision I make about food, wild or otherwise, has an impact, and for me, hunting forced an honest and open reckoning with my interactions with nature. That factory-farmed chicken from Save On bears no comparison to the bear I have hunted; I’ve just coopted the responsibility of husbandry and harvest from a third party. My life had changed significantly from my childhood as a city girl and I wondered what exactly was the “right path” and about the power of fate. Is that just something we tell ourselves to justify our decisions and beg off ownership over our own lives? Harold S Kushner said, “The small choices and decisions we make a hundred times a day add up to determining the kind of world we live in.” My life was definitely the result of a series of small decisions, pushing me further and further from where I started, closer to a greater awareness and connectedness with nature and to my loved ones. While I was in the kitchen, my husband burned the candle at both ends, working to build his training company, Silvercore, which he had started when we were first dating. I loved being a chef, but by the time our second child came along, I realized that my priorities had changed and I needed to redirect my energy into building my family and helping my husband with the business. When my kids were old enough to go to school, I started working full time with my husband at Silvercore, but it was not without significant trepidation. I was no firearms expert, or teacher, or hunter. I had no military or law enforcement experience. But we already had those people working with us, so I put aside those nagging negative thoughts and returned to the process I had adopted many years prior, asking myself, “Would the future me be proud of the new skills I am learning? Am I able to make a positive difference for others?” Although I hadn’t expected it, Silvercore allowed me to combine my love of food, foraging, hunting, fishing, and really just living and interacting in the outdoors with my work. I could take the things I loved to do and offer my knowledge and passion for service with others—and that gave me fulfillment. It didn’t hurt that the goal of Silvercore from the start was to offer unmatched value to the customer. It started to feel like my years of struggle, all that time

in the kitchen and the hundreds of hours researching and foraging food, had always meant to bring me here, to the point I’m at now with our business. Earl Nightingale defined success as “the progressive realization of a worthy ideal.” The path I’ve walked in life has brought me the benefit of sharing similar circles with like-minded people and organizations like the Wild Sheep Society of BC, whose core values align with my own. Groups that recognize that we do not hold dominion over the animals and natural world; rather, we are intrinsically intertwined and one with them, working toward the worthy goal of wild sheep conservation and giving back to others. We have a role to play in helping others connect with the wild and ensuring the harmony in nature is maintained. And that’s what brought me to this point, standing on an insulated mat, binoculars in hand, the cold wind sharp against my cheek, with a whitetail buck that hasn’t shown himself yet. I still have an hour left till last light and if he shows or not, there’s still tomorrow and the comforting realization that it’s more about my connection to this wild land, being here in the stiff cold snow listening for the soft sounds of a wild buck, than the yield of a hunt. Life has an interesting way of unfolding as it should, and I’m confident the path I’m on is where I’m meant to be.